ABSTRACT

Deviant behaviors manifest in many organizations and all occupations. Deviant behaviors in the workplace may originate from organizational norms and proclivities for self-benefit. The organizational culture influences employees’ attitudes. Employees internalize the organizational culture, which transforms their personal attitudes and influences their positive and negative behaviors towards the organization. This study explores the key factors affecting deviant workplace behaviors based on various dimensions such as organizational deviance, interpersonal deviance, leader-member exchange, and corporate culture. The multiple-criteria decision-making analysis method was applied and dimensions developed based on scale factors devised in previous literature. The opinions of experts from industry, the government, and academia were examined. The affecting factors were then weighed and ordered according to their importance. According to the research results, among the key factors affecting deviant workplace behavior, the organizational deviance variable of production deviance has the most significant impact on organizational development. The second most significant factor was anti-organizational behavior, a variable of interpersonal deviance, followed by members’ behavior and attribution, a leader-member exchange variable. Businesses are advised to formulate rules that prohibit organizational deviance, while building a supportive organizational culture and enhancing positivity in the workplace to reduce deviant behavior.

Key words: Leader-member exchange, corporate culture, organizational deviance.

Deviant behaviors manifest in many organizations and all occupations. Their prevalence in public organizations may be detrimental to the government and public (Estes and Wang, 2008). As such, organizations and their members will face the possible social and economic consequences of deviant behaviors, such as financial loss and negative social relations (Bolin and Heatherly, 2001). Adopting the theory of behavioral intention (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), a theoretical model of the factors affecting deviant workplace behavior was devised (Vardi and Wiener, 1996). According to the model, deviant behaviors in the workplace originate from organizational norms and proclivities toward self-benefits. With regard to deviant behavior, many historical works of literature (Chi, 2017) have illustrated theoretical assumptions and verifications over the years. These works can be categorized based on whether they deal with deviant behavior at the organizational level or at the individual level, and they differ in terms of region, ethnicity, and gender. It is worth studying this issue (or these works) continuously to find out the best direction for improvement.According to Jin Shu (648)/Lieh-chuan (648), in A.D. 322, the prominent Statesman Wang Tun (322) instigated a military uprising against Emperor Yuan of the Jin Dynasty. Based on their relationship with Wang Tun, his cousin Wang Tao and his clan went to the palace to plead guilty. When Chou Po-jen, an upright official, entered the palace, Wang Tao asked him to intercede on his behalf. Although Chou Po-jen seemed indifferent to his request, he persuaded the Emperor of Wang Tun’s loyalty and petitioned for him. Unaware of what Chou Po-jen had done, Wang Tao held a grudge against him. When Wang Tun later came into power, he was asked if he wanted to execute Chou Po-jen, to which he did not respond. Thus, Chou Po-jen was executed. After the execution, Wang Tao found in the imperial archives the petitions Chou Po-jen submitted on his behalf. The truth struck him so hard that he cried and lamented, “Although I did not kill Chou Po-jen, he died because of me!” This quote later became a Chinese idiom for “unintentional mistakes.” Wang Tun’s deviance, and the resulting tragedy, can be attributed to the long-term influence of the organizational culture in the palace and leader-member exchanges (LMX) between the Emperor, feudal vassals, and officials. Similar cases prevail in modern society. Therefore, scholars should discuss deviant behaviors in detail and propose solutions to improve and prevent similar issues from arising.

The frequent interaction between leaders and members during an organization’s operations means that their interdependence emerges based on the nature and importance of their jobs. Restricted by limited time and competency, leaders allocate resources selectively, resulting in leader-member exchanges (LMX). Those who more closely interact with leaders are called in-group members, while those with weaker relationships with leaders are out-group members (Varma et al., 1996). Because better rapport exists between leaders and in-group members, they establish loyalty and trust, and, rather than undergoing a simple change in their relationship, develop a mutually beneficial partnership (Liden and Graen, 1980; Dienesch and Liden, 1986). In-group members receive more favors from leaders such as important resources, promotion opportunities, and decision-making power (Graen and Scandura, 1987). Out-group members are limited to their prescribed roles because they perform in greater accordance with the employment contracts (Graen and Cashman, 1975). Leaders adopt a forgiving management approach and attitude towards in-group members’ performance and a strict, disapproving approach towards out-group members’ performance (Allison and Herlocker, 1994). While in-group members are favored and receive significant resources, out-group members are likely to be neglected and criticized based on a stricter standard. Consequently, the latter will perceive in-group favoritism (Yukl, 1994). If the leader-member exchange (LMX) causes the difference in treatment of insiders and outsiders to be too obvious, it will result in organizational inefficiency and affect the sustainable development of the organization.Deviant workplace behavior is defined as “intentional behavior that violates organizational norms and poses a threat to the well-being of an organization” (Robinson and Bennett, 1995). Most people conform to social norms and goals through self-discipline, the breakdown of which can result in organizational deviance (Marcus and Schuler, 2004). Leader-member exchanges (LMX) are established when leaders treat in-group and out-group members differently, forming different types of relationships with subordinates (Graen and Cashman, 1975).

This exchange, whether positive or negative, affects subordinates’ deviant workplace behaviors, which is harmful to the organization (Harper, 1990). This behavior is caused by workplace experiences, and therefore organizational deviance is likely to occur when members demonstrate their dissatisfaction with their experiences in the workplace or when they are in conflict with organizational requirements or individual behavior (Bennett and Robinson, 2003). The strictness of the norms set by the organization, based on the scale and type, will also affect the probability of occurrence of the deviant behavior. The less strict the rules are, the lower are the chances of deviant behavior and vice versa. Culture is the “collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group from others,” and a system of collective interaction that affects how the group reacts to the environment (Hofstede, 1980). Corporate culture refers to the sum of a company’s philosophy, objectives, policies, values, social responsibilities, corporate image, and other attributes formed during its operating activities. It is the enterprise’s institutional choices and behavioral practices observed by all employees (McLeod et al., 1985). Trevino (1986) believed that organizational culture played an important role in deciding the behavior of organization members, while previous studies (Boye and Jones, 1997; Vardi, 2001) suggested that it affects whether employees exhibit deviant workplace behavior. Thus, the effects of corporate culture on deviant workplace behavior should be examined in greater depth. Currently, most studies on deviant workplace behavior as influenced by organizational culture focus on Mainland China, Taiwan, and other countries with a Chinese-based culture. Because of China’s economic emergence in recent years, there has been increasing attention among scholars in Western countries to this phenomenon among Chinese people. Scholars in Taiwan and Mainland China have been actively participating in academic research and have formed a close research network with international academia, mainly American scholars, in recent years. This is also why these studies are mostly based on the Chinese experience (Chi, 2017). Because of the sensitivity of the topic of deviant behavior, this study ensured the anonymity of participants by collecting data through questionnaires. Anonymous questionnaires allow for participants’ full cooperation and therefore gather data with high validity (Dunlop and Lee, 2004; Johnson and Klee, 2007).

Leader–member Exchange (LMX)

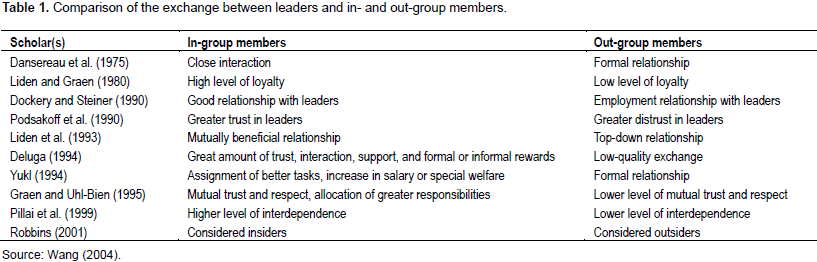

To explore the relationship between leaders and subordinates, Dienesch and Liden (1986) proposed the leader-member exchange (LMX) model, a dynamic development process of initial interaction, authorization by leaders, attribution, and exchange. Among these steps, attribution can be categorized as members’ behavior and attribution, leaders’ behavior and attribution, and leaders’ responses. A leader’s response is influenced by the behavior and attribution processes of members and leaders. Eventually, leaders determine whether their subordinates are in- or out-group members based on the leader’s attribution of the subordinate’s performance. Leader-member exchange (LMX) involves the dimensions of contribution, loyalty, and affect. If subordinates wish to become in-group members, they must complete their tasks and display their loyalty to their leaders, or develop good relationships with them through flattery (Dienesch and Liden, 1986). It was found that in-group members are allocated resources before other people, while out-group members enjoy limited resources and information. Therefore, the out-group members have a lower work incentive and job satisfaction, which substantially impacts the leader-subordinate relationship (Graen and Uhl-Bien, 1995). The definitions by foreign scholars of the exchanges between leaders and in- and out-group members are summarized in Table 1.

Deviant workplace behavior

Deviant workplace behavior occurs when employees either lack motivation to conform to acceptable behavior voluntarily, or become motivated to violate it as normative expectations of the social context (Kaplan, 1975). According to research, 85% of participating employees admitted to displaying deviant behavior, 90% said deviance was a usual occurrence, and 100% had witnessed deviant behavior by other employees (Ogbonna and Harris, 2002). Deviant workplace behavior has become a widespread and acute phenomenon. A study by Coffin (2003) found that 75% of employees reportedly engaged in theft, fraud, vandalism, embezzlement, deliberate absenteeism, and other deviant behavior. It was also found that male workers were more prone to alcohol abuse and females to absence from duty (Lau et al., 2003). Robinson and Bennett (1995) classified deviant workplace behavior into the following categories:

1) Production deviance: this includes lethargy, leaving early, and deliberately extending the duration of breaks;

2) Property deviance: this includes damaging company equipment and facilities and secretly accepting kickbacks and commissions;

3) Political deviance: this includes engaging in social interaction that puts other persons at a personal disadvantage. Examples include gossiping about and ridiculing other co-workers and competing very aggressively; and

4) Personal aggression: this includes sexual harassment and sabotaging of other co-workers.

Bennett and Robinson (2000) further divided deviant workplace behavior into two dimensions: interpersonal and organizational deviance. Interpersonal deviance refers to harmful acts targeting specific employees, such as mocking or verbally attacking other people. Organizational deviance refers to actions that deliberately violate organizational norms, such as private discussion of confidential business information, not taking work seriously, and stealing company property. Employees faced with unfair treatment in the workplace or work pressure may respond by exhibiting deviant behavior. In a study of employees in Hong Kong, perceived ambiguity, perceived supervisor interpersonal injustice, and perceived customer interpersonal injustice as daily sources of workplace pressure were identified (Yang and Diefendorff, 2009). According to their research results, these sources of pressure induce negative emotions and provoke employees’ every day interpersonal and organizational deviance. However, this process was also moderated by employees’ conscientiousness and agreeableness. Negative emotions were more likely to induce workplace deviance when employees were less conscientious and agreeable. All types of workplace deviance represent a rift in the employee–organization relationship. From the perspective of social exchange, management should attempt to fulfill its promises towards employees and treat them fairly while establishing favorable social bonds to foster their attachment and sense of identity towards the company. This can effectively reduce employees’ deviant behavior (Wu and Jiang, 2005).

Organizational culture

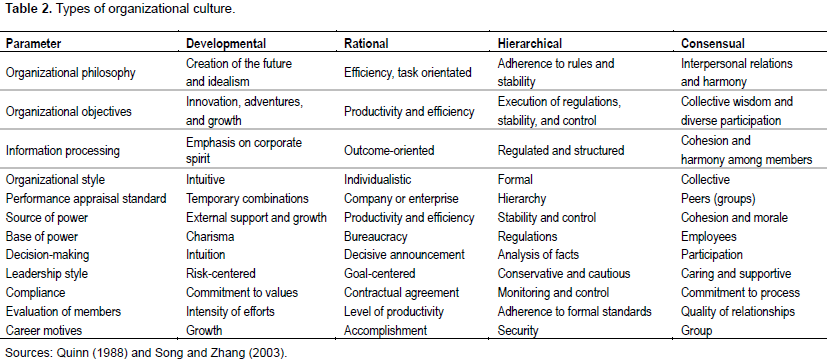

Quinn and McGrath (1985) developed the Competing Values Framework based on the human cognitive system,

and characterized the four forms of organizational culture as being developmental, rational, hierarchical, and consensual, as summarized in Table 2.

Analytic hierarchy process (AHP)

The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) is a decision-making method developed by Thomas L. Saaty, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, for a study on the contingency plans of the United States Department of Defense in 1971. The method is mainly used to handle uncertain multiple-criteria decision-making problems (Deng and Zeng, 1989). It helps decision makers systematize complex problems and delineate various aspects into a hierarchy, followed by a quantitative judgment for the identification and integrated evaluation of the underlying structure. The method enhances decision makers’ understanding of the situation and reduces the risk of making the wrong decisions (Deng, 2005). The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) is advantageous because it can integrate the opinions of experts and decision makers, and based on its mathematical theoretical basis, display any errors in their consensus through a consistency test. However, a drawback is the increased complexity of pairwise comparisons when a greater number of variables exist (Millet and Harker, 1990). The assumptions of the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) include the following seven conditions (Deng and Zeng, 1989):

1. All systems and problems can be delineated into classes or components for evaluation, forming a hierarchical structure with a directional network. 2. Each element in the hierarchy is assumed to be independent of all the others and can be evaluated based on an element or all elements above it.

3. During evaluation, the scale of absolute values can be converted to a ratio scale.

4. After pairwise comparison, the reciprocal matrix is symmetric about the main diagonal and a positive reciprocal matrix can be used.

5. Preference relations fulfill the condition of transitivity, but intransitivity is also allowed, because complete transitivity is difficult to achieve. However, the consistency of the preferences must be tested to determine the level of inconsistency.

6. The priority weight of each element is obtained by the weighted principle.

7. Any element in the hierarchical structure, irrespective of its priority weight, is related to the overall goal.

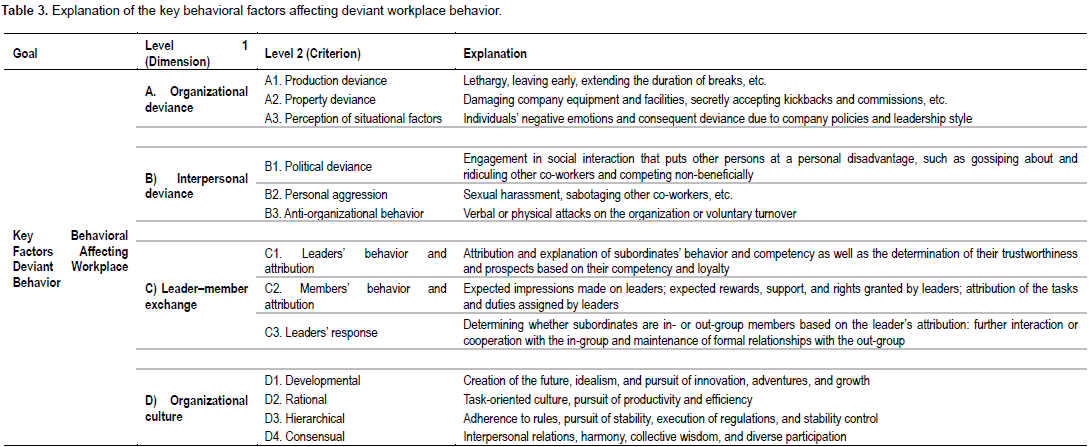

Based on the referenced academic papers and the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) research framework, level 1 (dimension) and level 2 (criterion) were derived for evaluation. For leader-member exchanges (LMX), three attribution processes in a model by Dienesch and Liden (1986) were adopted as the evaluation factors. In addition, the three dimensions required to become in-group members (Dienesch and Liden, 1986), namely contribution, loyalty, and affect, were also involved. The factors are explained in Table 3.

This study analyzes the key factors affecting organizational deviant behavior by employing the analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Questionnaires were distributed to gather the opinions of experts from industry, government, and academia. The factors were then ranked according to the priority weights assigned by the experts. For the items considered top priorities, this study makes suggestions for improvement. The opinions of scholars, experts, and decision makers at each level were collected for the pairwise comparisons between every two elements based on a nominal scale. After quantifying the opinions, pairwise matrices were constructed. A set of eigenvectors for each matrix was computed and translated into the priorities of the elements at each hierarchical level. Eventually, the maximum eigenvalue was calculated to determine the relative weights of the decision criteria, which serve as the consistency indices of the comparison matrices, to provide a reference for the decision-making process (Rong, 2011). As the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) relies on professional judgment, the appropriate number of participating experts is 10 to 15 respondents (Deng, 2005). To ensure higher quality and predictability of the research results, the experts must possess sufficient understanding and professional knowledge and skills in a field related to the research. In this study, senior managers with more than ten years of experience in administrative management, government officials in related departments like the Police Agency and City Government, and scholars in related fields such as organizational theory, strategic management, and operational research were invited to complete the questionnaire. Exploring both theoretical and practical viewpoints provides a comprehensive perspective from which to determine the key factors affecting deviant workplace behavior. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) method is employed by experts and scholars to assess the various elements of the hierarchical structure.

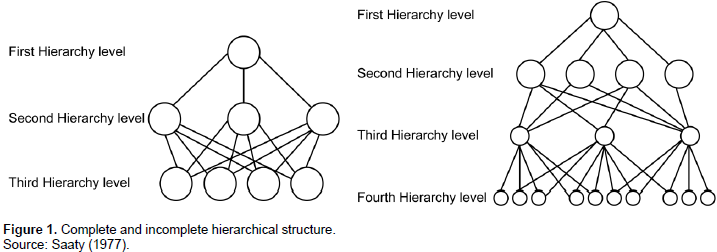

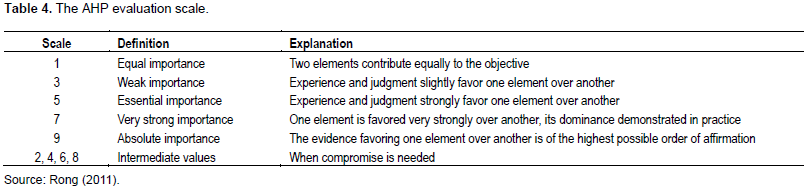

Analysis is conducted by setting up a matrix and the scale of assessment in order to perform the pairwise comparison. In addition, steps are taken to find the eigenvector in order to compare the level of order elements and verify the consistency of paired comparison matrices. The hierarchical structure shown in Figure 1 is divided into two kinds; one is the complete level, where the two adjacent elements are related, and the other is the incomplete level, which indicates that the adjacent two layers of elements do not necessarily have a complete relationship. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) evaluation scale comprises five levels: equal importance, weak importance, essential importance, very strong importance, and absolute importance, which are quantified into a nominal scale of indices 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9. There are four intermediate values between the five basic levels—2, 4, 6, and 8. Each level of the scale is explained in Table 4. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) includes the following steps: (1) creating a pairwise comparison matrix, (2) obtaining the maximum eigenvalue of the matrices, (3) computing the weight of each decision item, and (4) conducting consistency tests on the matrices. Wind and Saaty (1980) suggested that the consistency of the matrix should be examined using a consistency index (CI) and consistency ratio (CR)—the higher the consistency, the more acceptable the matrix values. A matrix is considered to have passed the consistency test when CR <0.1 and CI <0.1. Weighting in the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) mainly relies on experts or decision makers, who conduct pairwise comparisons of every two criteria to evaluate the relative importance of the items and use the maximum eigenvalue of the comparison matrices to determine the relative weights. As a result, the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) can more accurately measure the differences between criteria than conventional weighting methods. Therefore, this study uses the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) to compute the weights of decision items.

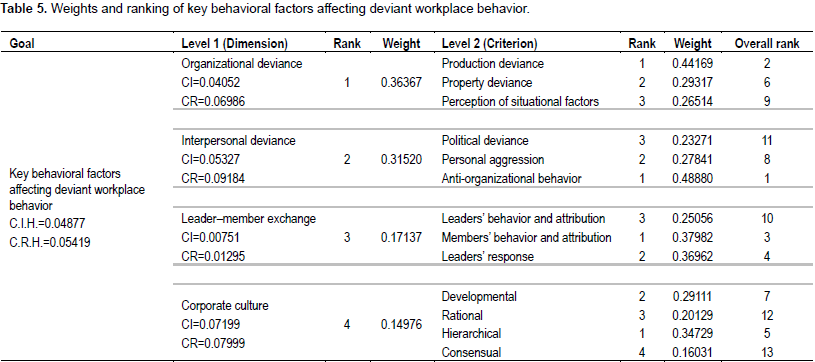

This study explores the key factors affecting deviant workplace behaviors based on various dimensions such as organizational deviance, interpersonal deviance, leader-member exchange, and corporate culture. The multiple-criteria decision-making analysis method was applied and dimensions developed based on scale factors devised in previous literature. Based on the results of the study, we would like to put forward suggestions for improvements of the approach. The study uses the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) hierarchy for computations. Based on previous academic papers, four dimensions and 13 criteria were derived and then ranked according to their computed weights. During the analytic hierarchy process (AHP), pairwise comparison matrices are constructed and the CI and CR of each matrix calculated to test its consistency and that of the overall hierarchy. If CI <0.1 and CR <0.1, the comparison matrix is considered consistent. The calculated weights of all the criteria in this study match the consistency requirement. The weights and rankings are listed in Table 5. Therefore, the organization should establish formal and transparent channels of communication to encourage employees to interact with each other in a rational and respectful manner. At the same time, organization leaders should avoid communication through improper methods to avoid vicious competition and political infiltration within the organization (He et al., 2014). The results indicate that among the key behavioral factors affecting deviant workplace behavior, organizational deviance has the highest weight (0.36367), followed by interpersonal deviance (0.31520). Among the criteria for organizational deviance, production deviance has the highest weight (0.44169), indicating that deviant behaviors such as lethargy, leaving early, and extending the duration of breaks have the greatest impact on the organization.

These findings are aligned with studies by other scholars (Coffin, 2003; Lau et al., 2003). In the overall ranking of the criteria, anti-organizational behavior was assigned the highest weight (0.48880). This shows that behaviors such as verbal and physical attacks on the organization and voluntary turnover have the most significant impacts on organizational development. This result is consistent with the findings of other scholars (Wind and Saaty, 1980; Elsbach and Bhattacharya, 2001). This study adopted the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) to evaluate the dimensions and criteria at each hierarchical level, before ranking them based on their priorities. The opinions of experts from industry, government, and academia show that production deviance, a variable of organizational deviance, is the most damaging to organizational development. Behavior that reduces employees’ productivity such as absenteeism and lethargy, hinder the overall performance of the organization and its sustainable development. Related academic papers also show that situational factors in the workplace are crucial determinants of employees’ production deviance. If organizational and career development can focus on building an environment in which both managers and employees can leverage their skills and strengths, while continuous and formal efforts are put into developing and improving human resources based on the needs of employees and the organization, the cost of employee turnover and incidence of production deviation can be lowered. Therefore, companies are advised to regularly evaluate how well employees have adapted to the organization, as well as to their duties, teams, and managers. This can deter the production deviance resulting from a low-level of adaptation. Effective education and training should also be provided to leaders to develop their empathy and ability to offer support, so that they can adjust their management based on a true understanding of employees’ feelings and ensure a friendly working environment that can mitigate production deviance. To effectively reduce interpersonal deviance, a supportive organizational culture and positive working atmosphere should be developed to expand manager–employee interaction patterns and encourage employees to voice their opinions and feelings and act in the public interest outside their duties. Furthermore, regulations, promotional measures, training, and courses related to the prevention of interpersonal deviance should also be developed to curb deviant behavior (Liu et al., 2010). There are two approaches to organizational discipline management, namely preventive and corrective. The former prevents misbehavior by encouraging members’ compliance with organizational standards and rules, while the latter stops further actions when misbehavior occurs to ensure the conformity of future behavior. Another factor that can abate deviant workplace behavior is material or financial rewards, which enhance employees’ sense of belonging and morale and reduces their job dissatisfaction. In addition, social exchange can lessen workplace deviance when used to improve the working environment and reduce pressure and negativity at the source. Moreover, as the pressure relief valve of the company, a complaint handling system can moderate employees’ resentment arising from their job dissatisfaction, thereby alleviating labor disputes. It is recommended that future studies explore and test these factors to complement existing research on deviant workplace behavior.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Allison ST, Herlocker CE (1994). Constructing impressions in demographically diverse organizational settings: A group categorization analysis. Am. Behav. Sci. 37(5):637-652.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bennett RJ, Robinson SL (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 85(3):349-360.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bennett RJ, Robinson SL (2003). The past, present, and future of workplace deviance research. In: Greenberg J, editor. Organizational behavior: The state of the science. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 247-281.

|

|

|

|

Bolin A, Heatherly L (2001). Predictors of employee deviance: The relationship between bad attitudes and bad behavior. J. Bus. Psychol. 15(3):405-418.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Boye MW, Jones JW (1997). Organizational culture and employee counterproductivity. In: Giacalone RA, Greenberg J, editors. Antisocial behavior in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; pp.172-184.

|

|

|

|

Chi SCS, Lo HH, Liang SG, Lai HF, Chu, CC (2017). Research findings and prospect of workplace deviant behaviour: A review of 2000–2015 studies with Asian samples. NTU. Manage. Rev. 27(2):259-306.

|

|

|

|

Coffin B (2003). Breaking the silence on white collar crime. Risk Manag. 50(9):8-9.

|

|

|

|

Dansereau F, Graen G, Haga WJ (1975). A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations: A longitudinal investigation of the role making process. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 13(1):46-78.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Deluga RJ (1994). Supervisor trust building, leader member exchange and organizational citizenship behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 67(4):315-326.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Deng, ZY (2005). Project evaluation: Method and applications. National Taiwan Ocean University Operation Planning and Management Research Center.

|

|

|

|

Deng ZY, Zeng G (1989). The analytical hierarchy process (AHP) connotation features and applications (I). J. Chinese Statist. Assoc.

|

|

|

|

Dienesch RM, Liden RC (1986). Leader-member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development. Acad. Manage. Rev. 11(3):618-634.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dockery TM, Steiner DD (1990). The role of the initial interaction in leader-member exchange. Group Organ. Manage. 15(4):395-413.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dunlop PD, Lee K (2004). Workplace deviance, organizational citizenship behavior, and business unit performance: The bad apples do spoil the whole barrel. J. Organ. Behav. 25(1):67-80.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Elsbach KD, Bhattacharya CB (2001). Defining who you are by what you're not: Organizational disidentification and The National Rifle Association. Organ. Sci. 12(4):393-413.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Estes B, Wang J (2008). Workplace incivility: Impacts on individual and organizational performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 7(2):218-240.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research reading. MA: Addison-Wesley.

|

|

|

|

Graen G, Cashman JF (1975). A role-making model of leadership in formal organizations: A developmental approach. In: Hunt JG, Larson LL, editors. Leadership frontiers. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press; pp.143-165.

|

|

|

|

Graen GB, Scandura TA (1987). Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. Res. Organ. Behav. 9:175-208.

|

|

|

|

Graen GB, Uhl-Bien M (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 6(2):219-247.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Harper FEW (1990). A brighter coming day: A Frances Ellen Watkins Harper reader. NY: Feminist Press at CUNY.

|

|

|

|

He H, Baruch Y, Lin CP (2014). Modeling team knowledge sharing and team flexibility: The role of within-team competition. Hum. Relat . 67(8):947-978.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hofstede G (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organ. Dyn. 9(1):42-63.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Jin Shu (648). Book of Jin. Chapter 69.

View

|

|

|

|

Johnson NJ, Klee T (2007). Passive-aggressive behavior and leadership styles in organizations. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 14(2):130-142.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kaplan HB (1975). Self-attitudes and deviant behavior. Oxford, England: Goodyear.

|

|

|

|

Lau VC, Au WT, Ho JM (2003). A qualitative and quantitative review of antecedents of counterproductive behavior in organizations. J. Bus. Psychol. 18(1):73-99.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Lieh-chuan (648). Book of Jin. Chapter 39.

View

|

|

|

|

Liden RC, Graen G (1980). Generalizability of the vertical dyad linkage model of leadership. Acad. Manage. J. 23(3):451-465.

|

|

|

|

Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Stilwell D (1993). A longitudinal study on the early development of leader-member exchanges. J. Appl. Psychol. 78(4):662-674.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Liu J, Kwan HK, Wu LZ, Wu W (2010). Abusive supervision and subordinate supervisor-directed deviance: The moderating role of traditional values and the mediating role of revenge cognitions. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 83(4):835-856.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Marcus B, Schuler H (2004). Antecedents of counterproductive behavior at work: A general perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 89(4):647-660.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

McLeod DD, Ramayya GP, Tunstall ME (1985). Self-administered isoflurane in labour. Anaesthesia. 40(5):424-426.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Millet I, Harker PT (1990). Globally effective questioning in the analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 48(1):88-97.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ogbonna E, Harris LC (2002). Managing organisational culture: Insights from the hospitality industry. Hum. Resour. Manage. 12(1):33-53.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Pillai R, Scandura TA, Williams EA (1999). Leadership and organizational justice: Similarities and differences across cultures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 30(4):763-779.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Moorman RH, Fetter R (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers' trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1(2):107-142.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Quinn RE (1988). Jossey-Bass management series. Beyond rational management: Mastering the paradoxes and competing demands of high performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

|

|

|

|

Quinn RE, McGrath MR (1985). The transformation of organizational cultures: A competing values perspective. In: Frost PJ, Moore LF, Louis MR, Lundberg CC, Martin J, editors. Organizational culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. pp.315-334.

|

|

|

|

Robbins SP (2001). Organisational behaviour: Global and Southern African perspectives. Cape Town: Pearson Education South Africa.

|

|

|

|

Robinson SL, Bennett RJ (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Acad. Manage. J. 38(2):555-572. Rong TS (2011). Expert choice in analytical hierarchy process (AHP). Taipei: Wu-Nan Book Inc.

View

|

|

|

|

Saaty TL (1977). A Scaling Method for Priorities in Hierarchical Structures. J. Math. Psychol. 15(3):234-281.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Song PJ, Zhang TS (2003). Discussion on the relevance of corporate culture and knowledge management framework. Taipei University of Science and Technology Knowledge and Value Management Symposium. pp.346-54, CD C2-6.

View

|

|

|

|

Trevino LK (1986). Ethical decision making in organizations: A person-situation interactionist model. Acad. Manage. Rev. 11(3):601-617.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Vardi Y (2001). The effects of organizational and ethical climates on misconduct at work. J. Bus. Ethics. 29(4):325-337.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Vardi Y, Wiener Y (1996). Misbehavior in organizations: A motivational framework. Organ. Sci. 7(2):151-165.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Varma A, Denisi AS, Peters LH (1996). Interpersonal affect and performance appraisal: A field study. Pers. Psychol. 49(2):341-360.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Wang JS (2004). A study on the relationship among relationship quality, organisational promises, and willingness to share knowledge. [dissertation]. Taiwan: I-Shou University.

|

|

|

|

Wind Y, Saaty TL (1980). Marketing applications of the analytic hierarchy process. Manag. Sci. 26(7):641-658.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Wu ML, Jiang D (2005). A study on the factors affecting organizational misconduct – A case study of service industry and manufacturing industry. Chinese J. Manage. 22(3):329-340.

View

|

|

|

|

Yang J, Diefendorff JM (2009). The relations of daily counterproductive workplace behavior with emotions, situational antecedents, and personality moderators: A diary study in Hong Kong. Pers. Psychol. 62(2):259-295.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Yukl G (1994). Leadership in Organizations (3rd ed.) Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

|