ABSTRACT

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted market trading activity around the world. The pandemic has disabled supply chains and forced businesses to look for pragmatic ways to keep their doors open. Companies have suspended business commitments citing the force majeure clause. The resulting tension in companies is a hotbed for rising confusion and turmoil. With businesses facing imminent closure and potentially acrimonious court cases, pragmatic businesses have called for round table talks with stakeholders to resolve the crisis. This review suggests that the sensitive uses of conflict management and negotiation skills are crucial to obtaining shared responsibility agreements. Empathy, gently invoking a social contract and deep conversations are helping companies successfully navigate a path through this unprecedented season.

Key words: Conflict, conversations, social contract, Covid-19, force majeure, new normal, share-share outcomes, 21st Century leadership.

On March 11th 2020, the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic following the outbreak of the COVID-19 flu in Wuhan China (World Heath Organization, 2020). Following this announcement, governments around the world scrambled to put in place self-preservation measures. These included international travel bans, suspension of trade and the implementation of social distancing programs (Kenya Government, 2020). Businesses around the world sent staff to work from their homes, cut salaries and dropped production targets. Companies pleaded for tax exemptions and suspended trade commitments in the wake of the pandemic (Craven et al., 2020). The World Bank has signalled that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic could trigger Africa’s first economic recession in 25 years (World Bank, 2020). Major banks have restructured Ks176 Billion in client loans and allowed companies to come up with revised repayment projections (Juma, 2020). A major drop in employee incomes has caused a sudden change in consumer tastes and lowered purchases of market goods (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has precipitated a business crisis that has disoriented management and left stakeholders wondering how to restore a sense of order and normalcy in the market. Nonetheless, history suggests that the effects of the pandemic could last for several years (US Government, Centers for Disease Control, 2020). While the force majeure clause has allowed escape from immediate litigation for failed service delivery, it has only bought time for companies to reorganize their business in the short term (Rochefort et al., 2020). Companies still have to resolve the important questions of business continuity, medium-term staff relations and long-term strategic business focus.

In this exploratory article the author surveyed newspaper reports, official government statements and media publications on the business impact of COVID-19 between March and June 2020. During this period various media outlets kept the public informed on the measures taken by local and international companies to scale down, scale back and reorganize business operations. Published surveys also reported on the varied impact of curfews and restricted movement on the production and distribution of goods. Media reports revealed that major businesses have quickly established a negotiating framework to address emerging conflict over stakeholder interests. However, the study also found that while stakeholders struggled to create order out of a chaotic environment, they also seem to have embraced an unusual chord of humanity, if not a conciliatory business tone in the light of the global catastrophe.

The problem

The unique nature of trade and social conflict caused by the pandemic has raised three major problems for business leaders; (a) How to resolve emerging conflict around stakeholder interests and concerns, (b) How to continue operations under force majeure conditions to advance stalled business operations, and (c) How to conduct negotiations with stakeholders to share the risks of proposals to keep businesses open.

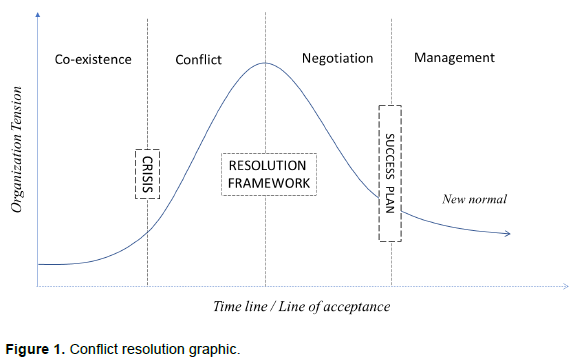

In order to quickly resolve looming operational losses and secure lifelines to a business future, business leaders have reverted to conflict and negotiation theory to help them resolve the current crisis (PWC Global, 2020). Conflict can be described as a difference in opinion, position or perspective on a matter affecting two or more parties. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, companies have had to negotiate with stakeholders to eliminate the possibility of total loss. While consensus on the broad issues was quickly reached, companies needed to agree with individual stakeholders on how specific interests and concerns were to be addressed (Deutsch et al., 2011). Framing these issues as a conflict allows all parties to acknowledge the need to deal with the emerging reality. Conflict management theory helps all parties work through the four phases of resolution (Figure 1) before the matter becomes acrimonious.

Looking back to the pre-crisis phase of co-existence enables stakeholders to review the positive and productive aspects of their relationship. It helps stakeholders resolve that the current crisis may affect interests and individual returns, but should not unduly derail their working relationship into the future. The second phase allows stakeholders to rationally examine the conflict elements brought about by the crisis and identify issues that need resolution. The third phase provides for the pragmatic negotiation of a resolution frame to bring down organization tensions (Lewicki et al., 2016). This stage addresses stakeholders’ uncertainty and anxiety about their interests. The fourth phase allows the business to move into the new normal with managed expectations and a success plan to control the impact of the crisis. The four phases of conflict resolution enable a business and its stakeholders to develop an acceptable business recovery plan (Sheiner and Yilla, 2020).

An effective resolution frame works to contain untoward emotions, anger, and frustration and brings down heightened organization tensions (Davies, 2016). The process of conflict management includes crucial conversations, negotiations, arbitration or other processes to contain unacceptable differences (Patterson et al., 2002). The second phase allows stakeholders to come face to face with “force majeure” and helps all parties appreciate that the nature of conversation is hardly business as usual. Stakeholders acknowledge that business continuity is a matter of agreement rather than a search for legal options. In these moments of crisis contenders and competitors have pulled down defences to negotiate their mutual survival (Laskar, 2013). Stakeholders are re-learning how to do business at the speed of trust and rely on a social contract to keep their pledge as far as is humanly possible (Covey and Merill, 2006). The “new normal” is unlikely to return stakeholders to pre-crisis business conditions. However, the crisis resolution process has become part of a surviving business success kit and equipped these businesses to navigate the prevailing disruptive business environment (Faeste and Hemerling, 2016).

These negotiations have required that companies develop deeper skills in empathy, negotiation, conversation and collaboration with stakeholders (Lewicki et al., 2016). This kind of deep conversations would not have been considered practical in the normal cut-throat, competitive business environment where the strong survive and the winner takes all (Fischer and Ury, 1991). Companies are learning to cooperate and collaborate as success keys to a business future. Organizations have had to rethink and develop more inclusive business strategy. The pandemic has forced the business community to be more reflective by engaging colleagues and associates in deep conversations guided by five important considerations. 1) Both parties stand to lose greatly in the event that an agreement is not reached, 2) Winning an argument or trying to get the upper hand in a discussion may not result in substantive business advantage to any party, 3) Losing or giving up an argument does not open up options further afield, 4) Surviving a crisis demands humility and a considerably dispassionate approach to openly address the reality at hand, and 5) Overcoming crisis calls for substantive emotional intelligence among leadership teams (Stone et al., 1999).

The COVID-19 pandemic is teaching companies to mix empathy with pragmatic business negotiation to develop collaborative survival strategies with all their stakeholders (Goleman, 2017). In the past, stakeholder concerns were taken care of separately and independently before being presented at a contested forum. Trade unions contended for employee benefits against what management had to offer, stakeholders pleaded for a business hearing, while strategy remained an exclusive boardroom affair (Howell and Sorour, 2016). The pandemic has opened up a new space where deep conversations have several benefits. First, these empathetic discussions create a safe space and communicate to all parties that “we are in this together” (Malunga, 2009). Second, they harness a business’s emotional energies to look for constructive options out of the crisis. Third, deep conversations conducted in good faith raise the levels of collaboration amongst stakeholders to share roles, risks and success of the enterprise. Fourth, the resulting collaborative strategy harnesses the strengths, capacity and competencies of each stakeholder, while compensating for the vulnerabilities among them. Nonetheless, the pandemic has also highlighted a need for new, more empathetic, leadership theory in the 21st Century business environment (Montuori and Fahim, 2010).

The COVID-19 pandemic has opened up new negotiation space giving stakeholders and industry players an opportunity for freer sharing of information, inter-business understanding and structuring mutually beneficial share-share agreements. The new normal environment has also introduced a heightened level of engagement between businesses and stakeholders. Empathy, social contracts and deep conversations call for open, non-judgemental communication and trust among market players. The share-share outcomes of these business conversations have allowed businesses to remain open in the short term and manage stakeholder expectations. Share-share outcomes have also helped businesses to model more inclusive medium-term business plans and design sustainable long-term business strategy.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Covey SM, Merill RR (2006). The speed of trust: The one thing that changes everything. New York, Free Press.

|

|

|

|

Craven M, Liu L, Mysore M, Wilson M (2020). COVID-19: Implications for business. McKinsey and Company.

|

|

|

|

|

Davies W (2016). Overcoming anger and irritability: A self-help guide using cognitive behavioural techniques. Hachette UK.

|

|

|

|

|

Deutsch M, Coleman PT, Marcus EC (2011). The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice. John Wiley and Sons.

|

|

|

|

|

Faeste L, Hemerling J (2016). Transformation: Delivering and sustaining breakthrough performance. Boston, MA: Boston Consulting Group.

|

|

|

|

|

Fischer R, Ury W (1991). Getting to Yes. New York: Penguin Books.

|

|

|

|

|

Goleman D (2017). Leadership that gets results (Harvard business review classics). Harvard Business Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Howell KE, Sorour MK (2016). Corporate Governance in Africa: Assessing Implementation and Ethical Perspectives. Springer.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Juma V (2020). Kenya's biggest banks restructure Sh176bn loans on coronavirus. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Kenya Government (2020). Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved from National Emergency Response Committee on Coronavirus. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) (2020, May 15). Survey on Socio Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Households Report. Retrieved from Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Laskar ME (2013). Summary of Social Contract Theory by Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Lewicki RJ, Barry B, Saunders DM (2016). Essentials of Negotiation. New York: McGraw Hill.

|

|

|

|

|

Malunga C (2009). Understanding Organizational Leadership through Ubuntu. London: Adonis and Abbey Publisher Ltd.

|

|

|

|

|

Montuori A, Fahim U (2010). Transformative Leadership. ReVsion. pp. 1-3.

|

|

|

|

|

Patterson K, Grenny J, McMillan R (2002). Al Switzler. Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High. New York: McGaw Hill.

|

|

|

|

|

PWC Global. (2020). Six Key areas of Focus for Organisations. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Rochefort LP, Boland MK, McRoskey RE (2020). The Coronavirus and Force Majeure Clauses in Contracts. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Sheiner L, Yilla K (2020). The ABCs of the post-COVID economic recovery. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Stone D, Patton B, Heen S (1999). Difficult Conversations. London: Penguin Books.

|

|

|

|

|

US Government, Centres for Disease Control (2020). Past Pandemics. Retrieved from CDC: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (2020). World Bank predicts Recession for Africa. Retrieved from World Bank:

View

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (2020). WHO Director-General's Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Available at:

View

|

|