ABSTRACT

Although some studies show the benefits of adopting integrated reporting (IR), its real value has not yet been sufficiently investigated. As integrated reporting development implies high costs for the company, the management has to evaluate the economic advantage of such investment. This study aims to establish whether a high quality IR influences firm market value. Specifically, we investigate whether shareholders take into account the good quality disclosure provided by IR in their investment assessments and reward the outstanding firms. We proxy high quality disclosure by the awards assigned to IRs published by a sample of South African listed companies for the period 2013 to 2016. Using event study methodology, we found out that the stock market reacts positively to award announcements, the value attributed by shareholders to the quality of IR is persistent, grows over time and is particularly high in non-financial companies. This evidence should encourage managers to invest in improving IR disclosure quality.

Key words: Integrated reporting, corporate social responsibility, market value, disclosure quality, event study, shareholder.

Environmental and social (ES) reporting has attracted increasing attention over the past 20 years (Eccles et al., 2011a,b; Delgado-Ceballos et al., 2014). Initially, ES disclosure was incorporated into corporate annual (financial) reports. Subsequently, it became less dependent on these and appeared in various media and stand-alone reports. The poor integration of ES disclosure with financial disclosure complicates the reading of policies, practices and impacts by stakeholders (Yongvanich and Guthrie, 2006; Eccles and Krzus, 2010; Cohen et al., 2012). Although sustainability reports drafted in accordance with Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards can be full of information on ES and economic policies and practices, the connections between these aspects can be difficult for the reader to discern. The need for a complete picture of all these issues led to integrated reporting (IR) (De Villiers et al., 2014). In 2010, the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) was established and, in late 2013, it issued the final version of the Integrated Reporting Framework (IIRC, 2013a, b). Scholars (Eccles and Krzus, 2010; Frías –Aceituno et al., 2014) and standard setters (GRI, 2016; IIRC, 2013a) agree that traditional financial and sustainability reporting is no longer able to deliver the information that investors ask in order to make informed decisions.

IR aims to help address that gap (IIRC, 2013a; Eccles and Krzus, 2014) by providing concise information “about how an organization's strategy, governance, performance and prospects, in the context of its external environment, lead to the creation of value over the short, medium and long term” (IIRC, 2013a). The principle of “connectivity of information” is a key element in understanding firm activities: the interrelationships between different types of capital (financial, manufactured, intellectual, social and relationship, human, and natural), and the effects of firm activities on these “multiple capitals” need to be clearly identified by companies. In this context, IR should qualitatively improve the available information to investors (IIRC, 2013b). Its main ‘target audience’ consists of investors and capital providers. As IIRC (2013a) claims that the main IR users are financial capital providers, we focus on shareholders. IR is more than just a report: it focuses on integrated thinking (IIRC, 2013a; KPMG, 2011) and requires cross-functional collaboration within the organization, and investments in information systems, skills and expertise. As IR development implies high costs for the company, the management has to evaluate the economic advantage of such investment. Eccles and Saltzman (2011) investigate the advantages of IR, which in their view consist of:

(1) Internal benefits, such as improvements in decisions regarding internal resource allocation, increased engagement with stakeholders and reduced reputational risk.

(2) External market benefits, such as catering for mainstream investors seeking environmental, social and governance (ESG) information, featuring in sustainability indices, and making sure that data vendors provide accurate non-financial information about the company.

(3) Management of regulatory risk, such as making preparation for possible global regulation, responding to requests from stock exchanges, and having a voice in the development of frameworks and standards.

This emerges also from an investor survey conducted by PwC on corporate performance (PwC, 2014) addressed to 85 institutional investors (buy-side, sell-side and ratings agencies). This survey confirms that investors see a direct link between the quality of reporting and the quality of management. However, at the same time, investors are aware that managers have to maintain a competitive advantage and, for this reason, they are reluctant to reveal too much information about their business models, strategies and risks. The IIRC highlights strategic, operational and organizational benefits such as the different and better exchange of information between the board of directors and management, a better establishment of the causal relationship between business model, strategy and performance, a more united way of working across different functions; a decision-making process based on a better quality and interconnectivity of information; access to better and new information, more transparency for stakeholders (IIRC, 2013b). Although several studies show the benefits of adopting IR (Hoque, 2017), less is known about its market impact (Serafeim, 2015; Zhou et al., 2017), and its real value has not yet been sufficiently investigated.

This study aims to fill this gap. Specifically, we try to answer the following question put by De Villiers et al. (2014): ‘Is the decision to disclose an IR value relevant, in other words, do the financial markets react or reflect a value premium in any way?’. For this reason, we test whether high-quality IR influences firm market value. Specifically, we investigate whether shareholders, IR’s main target audience, take into account the quality of disclosure provided by IR in their investment assessments and duly reward outstanding firms. We focus on a sample of listed companies based in South Africa, where IR is mandatory. As a proxy of disclosure quality we consider the IIRC-recognized awards assigned to IR. We use event study methodology to measure the effect on the stock price of IR award announcements. The study sample consists of 76 announcements regarding South African listed firms that received IR awards, as winners or finalists, between 2013 and 2016. The results of this study show that shareholders appreciate the quality of financial and non-financial disclosure provided by IR: the stock market in fact reacts positively to award announcements. We also demonstrate that investors reward both firms being finalists and winners in an IR award competition.

Finally, the study shows that the value attributed by shareholders to the quality of IR is persistent, grows over time and is particularly high for non-financial firms. From a managerial point of view, this study confirms the usefulness for companies of investing in integrated report quality (IRQ) and encourages managers to improve in this area. From the theoretical point of view, this study extends the empirical research on IR and its benefits. From the policy point of view, the work suggests that it is necessary not only to reinforce the quality of the IR, but there is also a need to develop shareholder awareness and reporting culture.This paper falls in the area of empirical studies investigating the relationship between IRQ and market reaction. The study contribution to previous literature is manifold. First, we use an original proxy for quality disclosure: IR awards. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to adopt IR awards as a proxy of disclosure quality for analyzing stock market reaction.

This proxy, frequently used in studies of Total Quality Management (Hendricks and Singhal, 1996; Adams et al., 1999), resolves the limitations of alternative metrics used for assessing disclosure quality, because it relieves the researcher of the need to make subjective judgements. Award-giving and benchmarking organizations are in fact solely responsible for the adjudication processes and commentaries, but the IIRC recognizes that the criteria for the assessments are reasonably aligned with the international IR framework. Second, unlike previous literature, which mainly used the standard valuation model developed by Ohlson, 1995 (Mervelskemper and Streit, 2017; Lee and Yeo, 2016; Semenova and Hassel, 2015) and OLS regression (Dhaliwal et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2017), this study applies event study methodology to investigate the value-relevance of IRQ. Furthermore, we use a proprietary database, consisting of the dates of the first announcement made to the market of an IR award. Finally we observe the effects of the integrated reporting over time and for different sectors.

Previous literature shows a positive link between quality of financial disclosure and firm value. More specifically, empirical research generally demonstrates a positive relationship between disclosure quality and analyst earnings forecasts (Barth et al., 2001; Hope, 2003; Plumlee, 2003). Otherwise, many studies demonstrate the theoretical negative link between the level/quality of discretionary disclosures and cost of equity capital in terms of risk sharing (Merton, 1987), reduction of estimation/information risk (Barry and Brown, 1985; Coles et al., 1995), market liquidity and information asymmetry (Healy and Palepu, 2001; Diamond and Verrecchia, 1991; Easley and O’Hara, 2004). The format of the information is also important: some authors (Hodge et al., 2006; Kelton et al., 2010) show that market prices can be differently influenced by equivalent disclosure if it is presented in different ways. Moreover, many analyses focus on the direct and indirect effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) disclosure on the stock market. Some studies investigate the share price impact of the announcements of sustainability report publications. These analyses show that in some cases the effect is almost nil (Carnevale et al., 2012), or is felt more strongly in certain stock markets than in others. In other cases, the announcement is rewarded only if the reports are certified while in others the investors assign a premium price only in the presence of high-quality sustainability disclosure (Guidry and Patten, 2010).

Other empirical evidence highlights the value relevance of ES disclosure (Carnevale and Mazzucca, 2014; Qiu et al., 2016; Plumlee et al., 2015; Huang and Watson, 2015). More recent studies show how the quality of CSR disclosure positively influences the share price (Cheng et al., 2013; Griffin and Sun, 2013). These results confirm that, unlike some years ago (Milne and Chan, 1999; Banghøj and Plenborg, 2008), investors nowadays take full account of information on sustainability issues in their investment decisions (Qiu et al., 2016; Dhaliwal et al., 2011; Dhaliwal et al., 2012) and attribute a value to high-quality reporting. Unlike the aforementioned studies which analyze financial and non-financial information separately, literature on IR considers them jointly. The study fits into the strand of literature on the relationship between IR and firm value. On the one hand, the IIRC (2013a) states the existence of a positive association between the two variables. This is thanks to the information set provided by IR to shareholders, which allows them to reduce costs of collecting and processing information (Sims, 2006; Veldkamp, 2006). Moreover, the main IR principles, such as materiality, conciseness, and connectivity (IIRC, 2013a), aiming to focus only on important matters related to the company value-creation capacity, contribute to mitigating the information overload and complexity problem. Furthermore, IR (IIRC, 2013a) can reduce the cost of capital in different ways:

(1) By attenuating information asymmetry (Easley and O’Hara, 2004; Gietzmann and Ireland, 2005)

(2) By expanding the firm investor base through comprehensive and free information on the firm activities (Merton, 1987), and

(3) By reducing parameter uncertainty and estimation risk (Verrecchia, 2001; Beyer et al., 2010).

On the other hand, IR may be negatively associated with firm valuation because of the cost of proprietary disclosure (Verrecchia, 1990). IR contains information (on strategy, business models, opportunities and risks) that could give an advantage to competitors, increase costs of regulatory action and legal liabilities, and discourage firms from pursuing profitable business not compliant with claimed values or norms. Moreover, IR can increase direct compliance costs. More specifically, this study study focuses on the link between IRQ and market reaction. To date, many studies have focused on data from South Africa where IR is mandatory. Bernadi and Stark (2015) analyze user perceptions of IR value on a South African sample through analyst forecast accuracy. They focus on the period 2008 to 2012, when reporting regimes asked firms to implement IR on an “apply or explain” scheme. The authors demonstrate that ESG disclosure transparency, measured by the Bloomberg ESG score, is associated with forecast accuracy after the introduction of the IR regime.

Lee and Yeo (2016) also found a positive association between firm valuation and IR disclosure. Their results suggest that firms with greater external financing needs, when they publish high quality IRs, show better firm valuations than those publishing low quality IRs in terms of both stock market and accounting performance. The authors measure IRQ by means of a firm-specific score based on the degree of alignment with the IR disclosure framework. Moreover, Barth et al. (2016) demonstrate the positive association between IRQ, stock liquidity and expected cash flows. Their proxy for IRQ is based on a score underlying the annual EY Excellence in Integrated Reporting Awards. Furthermore, Zhou et al. (2017), analyzing a sample of companies listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE), found that when the compliance level with the IR framework grows, analyst forecast error decreases and saving in cost of equity capital increase. In addition, Baboukardos and Rimmel (2016) investigate whether the value relevance of summary accounting information in South Africa has increased after the mandatory adoption of IR. Their results show a growth in the value relevance of earnings, but a decline in that of net assets, maybe because of better risk disclosures.

Other studies focus on worldwide samples.

Mervelskemper and Streit (2017) demonstrate that companies publishing IRs, if compared with those preferring stand-alone ESG reports, show a higher degree of value-relevance of ESG performance scores. Moreover, Arguelles et al. (2015) find that disclosures compliant with IIRC principles are appreciated by capital markets increasingly over time. However, other authors state that IR, compared to a separate ESG report, does not increase investor valuation of ESG performance (Stubbs et al., 2014). The relationship between IR and firm valuation remains an empirical topic. In this context, extending the results of Lee and Yeo (2016), we expect that:

Hypothesis 1: Shareholders positively react to the good quality disclosure provided by IR.

Hypothesis 2: The “reward effect” associated with companies providing IR good quality disclosure is persistent.

Investors are often not instantaneously able to process the content of IR information (Arguelles, 2015) and, for this reason, capital markets may not recognize changes in the value relevance of disclosures immediately, but rather in subsequent years (Branco and Rodrigues, 2006). Therefore, we predict that:

Hypothesis 3: Shareholders reward the good quality disclosure provided by IR increasingly over time.

Finally, González-Benito and González-Benito (2006) observes that stakeholder control levels and expectations are different across industries showing different polluting potentials. Specifically, oil, chemical and paper industries are often perceived as associated with stronger environmental impacts than the financial sector (Matute-Vallejo et al., 2011). Traditionally, financial companies are considered to have low direct environmental impact and environmental risk. More recently, some studies have however focused on the indirect impact of the banking activity, related to lending (Sarokin and Schulkin, 1991; Thompson and Cowton, 2004; Viganò and Nicolai, 2009). Banks are in fact responsible for financing company sustainable development (Relano and Paulet, 2012; Scholtens, 2009) through socially responsible investments and lending policies (Simpson and Kohers, 2002). In this context, we expect that:

Hypothesis 4: Shareholders reward the good quality disclosure provided by IR more in non-financial than in financial companies.

Sample

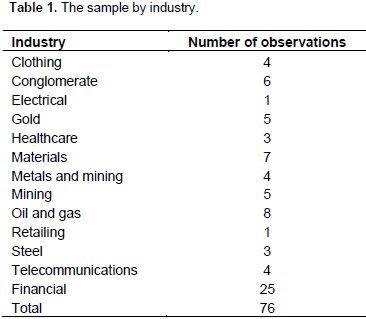

The study sample consists of 76 observations relating to companies belonging to different industries, as shown in Table 1, and listed on the JSE, which have been finalists and winners in awards ceremonies for the best IR. The study data is from South Africa, where IR is mandatory. 2010 King III recommendations require in fact to companies listed on the JSE to produce an IR in place of their annual ï¬nancial and sustainability reports. If firms do not comply with this suggestion, they explain the reasons. The focus on a South African sample allows us to avoid any concerns about:

(1) Immaturity of the market, despite a high heterogeneity among corporate reports produced by companies, as showed by Doni et al. (2016)

(2) Self-selection arising when IR is voluntary (Pope and McLeay, 2011), and

(3) The differences between ESG disclosures across countries due to different cultural and social norms or regulations (Ioannou and Serafeim, 2016).

To ensure that the awards assigned were consistent with the spirit, logic and practice of the IIRC, we selected only the award-giving and benchmarking organizations shown on the ‘Recognized Reports’ on the IIRC website for the period 2013 to 2016. We excluded previous years because it was only in November 2012 that the IIRC released a prototype of the International IR framework, outlining the key considerations that are critical to IR. We selected companies listed on the JSE and looked for the date of the first announcement in the press of their IR award or nomination for the award. We used Factiva and conducted a survey of the websites of the study sample companies and websites of the Award Organizations. The Award Organizations and Award categories considered (shown in Table 2 by year) are:

(1) EY excellence in integrated reporting awards

(2) PwC's building public trust 'excellence in reporting' awards

(3) CSSA integrated reporting awards

(4) Nikonki top 100 JSE listed companies integrated reporting awards (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1 shows the number of observations of 76 listed companies that have been finalists and winners in awards ceremonies for the best integrated reports over different industries in the period 2013 to 2016. The data source is the "recognized reports" on the IIRC website for the years 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016. Table 2 shows the number of observations of 76 listed companies over different industries that were finalists and winners in four different awards ceremonies for the best IR in the period 2013 to 2016. The data source is the "recognized reports" on the IIRC website for the years 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016.

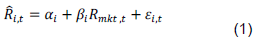

The effect on stock prices of IR award announcements is measured by using the event study methodology (MacKinlay, 1997). The study sample consists of 76 observations regarding South African listed firms which received an integrated report award, as winners or finalists, between 2013 and 2016. In order to get accurate evidence, we eliminate all events that were announced at the same time as other new, price relevant information. We run some event studies to estimate abnormal returns following IR award announcements, which are thought to explain stock return changes. These abnormal returns are obtained as the difference between the actual stock return registered from the listed company i on day t, that is, the day when the IR award is announced, and the expected return that the security should have registered given the absence of the event. Following previous literature (Campbell et al., 1997), we use Sharpe (1963) market model in order to estimate expected returns:

Where:

is the stock return of company i (which received an IR award) on day t; αi is the intercept of the regression line; βi is the slope of the regression line; Rmkt,t is the national market index return on day t; εi,t is the random error.

The αi and βi coefficients for each firm are estimated by an ordinary least square (OLS) regression of on Rmkt for a 250 day time horizon (that is, from the 270th to the 21st day before the information announcement). We define the date of the IR award announcement as day 0, and the event window as the period ranging from -t1 days before and +t2 days after day 0. Following a standard approach, we consider different window lengths. The widest event window extends from 10 days before day 0 to 10 days after. We consider event windows both before and after the IR award news, as we expect that some market participants could have access to this information prior to its official announcement. The abnormal return (ARi,t) due to the IR award announcement of company i for day t is measured as follows:

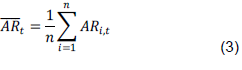

The average abnormal return ( ) at each time t in the event window is estimated by aggregating the abnormal stock returns for all n company shares and calculating the average value:

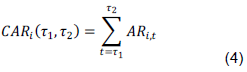

By summing all ARi,t over the days in the event window, that is, within the event period , we determine the cumulative abnormal return for each share i:

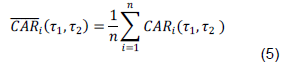

We finally obtain the mean CARs in the different event windows ( by estimating the arithmetical average value of CARi (τ1, τ2) for all n stocks:

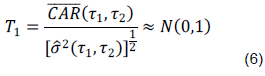

We verify CAR statistical significance using three tests. The first parametric test (T1) corroborates the null hypothesis stating that the new information announced to the market does not impact the cumulative abnormal returns (Campbell et al., 1997):

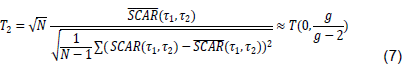

As the popular T1 can be biased in evaluating CAR statistical significance in short-time horizon (Harrington and Shrider, 2007), we also applied a second parametric test (T2), suggested by Boehmer et al. (1991), that is shown to be robust to an event-induced variance increase:

with g>2, where N is the number of shares and is the standardised abnormal return on security i at day t. is estimated using the approach suggested by Mikkelson and Partch (1988):

Where:

τ1 and τ2 are respectively the first and last days in the event window, is the cumulative abnormal return of share i in the event window , is the mean return on market index in the estimation period, is the estimated standard deviation of abnormal return on share i, T is the number of days in the estimation period and Ts is the number of days in the event window. The T2 shows a T-distribution with T-2 degrees of freedom, and converges to a unit normal.

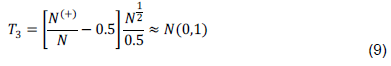

Moreover, we carry on a non-parametric test (T3) to confirm evidence obtained by T1 and T2. The sign test (T3) (Campbell et al., 1997; MacKinlay, 1997) is estimated as follows:

Where:

N is the number of events and N(+) is the number of events with a positive CAR. The null hypothesis states that IR award announcements are not followed by significant cumulative abnormal returns. Therefore, if a significant number of positive CARs is found, the null hypothesis is rejected. We consider as statistically significant CARs that passed all the three tests described earlier. All these tests do not have an economic meaning, but only a statistical value. When the test value exceeds the threshold of 1.294, 1.667 and 2.381, the mean CAR is statistically significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% level, respectively. For this reason, all values (both positive and negative) lower than 1.294 are for the purposes of interpretation, completely equivalent, and inform that the mean CARs to which they refer are not statistically significant.

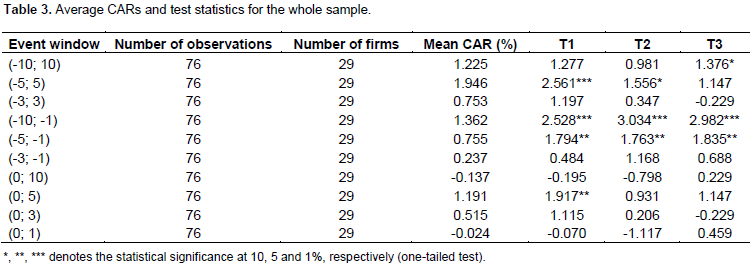

In order to evaluate company share price reaction to IR award news, we conducted separate analyses for the whole sample and some subsamples. Focusing on the global sample (Table 3), the study results show that the mean CARs are positive in almost all event windows. This means that IR award news is appreciated by the market. Table 3 also reveals the results of event studies conducted on the data for 76 cases of IR awards announced between 2013 and 2016. We measured the company normal returns using the market model. The CAR statistical significance was verified using three tests (T1, T2 and T3), reported in Equations 6, 7 and 9. However, the statistical significance of the study estimates and CAR values vary across different event windows. Two event windows prior to day 0 show high statistically significant CARs at a 95% confidence level or above. Specifically, event windows (-10; -1) and (-5; -1) display average CARs of 1.36 and 0.76%, respectively. This means either that IR award news is easy for investors to forecast, or that some market participants probably have access to prior information.

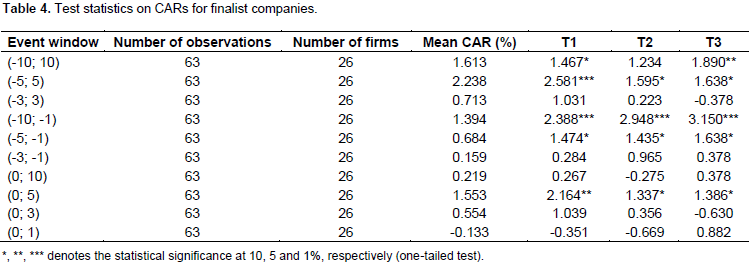

We do not find statistically significant results either after day 0 or in the symmetric event windows. This evidence suggests that shareholders take into account the good quality of disclosure provided by IR in their financial choices, as suggested by Hypothesis 1. However, these investors do not reward the outstanding firms after the IR award official announcements, but some days before them. Moreover, we also investigated the existence of a positive market effect of IR award announcements not only for top-prize winning companies, but also for competitors positioned at the top of the ranking. For this purpose, we subdivided our sample into two sub-samples: news about winning firms (13 observations) and news about firms that received a merit or were finalists in an IR award competition (63 observations). In the case of winners, a ‘reward effect’ would probably be obvious; furthermore, there is less data on firms not awarded top prize. For this reason, the analysis focuses only on finalist firms (Table 4) which shows the results of event studies conducted on the data for 63 cases of IR awards announced between 2013 and 2016. Here, the company’s normal returns were measured using the market model. The CAR statistical significance is assessed using three tests (T1, T2 and T3), reported in Equations 6, 7 and 9.

The study results show that shareholders react very favorably to news about companies receiving a merit or being finalists in an IR award, as the mean CARs are positive in all event windows. Specifically, we notice statistically significant CARs of 1.39% and 0.68% in the event windows (-10; -1) and (-5, -1), respectively. The study interpretation of this result is that the news about firms being finalist in an IR award competition is likely to spread before the award ceremony. Statistically significant results are also registered in event windows following the announcement date. Event window (0; 5) in fact shows statistically significant average CARs of 1.55%. This means that shareholders react positively to the announcement of IR award finalists in the 5 days after the day 0. Overall, higher average CARs are found in the symmetric event window (-5; 5), which shows positive and statistically significant mean CARs of 2.24%. These results can be interpreted as further evidence that shareholders take into account the good quality disclosure provided by IR in their investment assessments, as suggested by Hypothesis 1. This is confirmed by the fact that these investors reward firms that receive a merit or are finalists in an IR award competition without being winners.

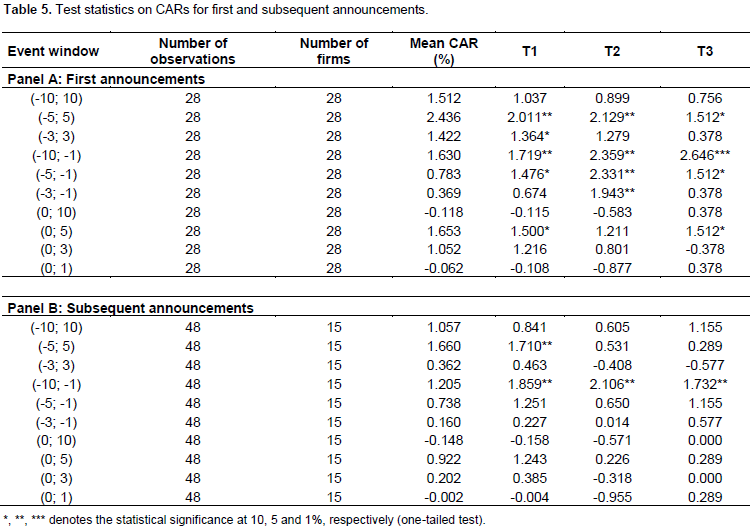

We also investigated the persistence of the ‘reward effect’. In other words, we tested whether shareholders react positively only the first time a company is winner or finalist in an IR award competition, or also on subsequent occasions. Our evidence shows positive and statistically significant results for companies announcing for the first time a good ranking in an IR award competition (Table 5, Panel A) in event windows that are symmetric and prior to the announcement date. Statistically significant estimations are found in fact in event windows (-5; 5), (-10; -1) and (-5; -1), with average CARs of 2.44, 1.63 and 0.78%, respectively. These results confirm that IR awards, even to first time winners, are probably easy for investors to forecast, or that some market participants have access to prior information. However, CARs relating to companies announcing that they are winners or finalists for the second, third or fourth time are statistically significant only in the event window (-10, -1), showing a mean value of 1.21% (Table 5, Panel B). This means that shareholders consider the good quality disclosure provided by South African IR not only when a company gets a good ranking in a competition for the first time, but also on subsequent occasions, as suggested by Hypothesis 2 (Table 5) which shows the results of event studies conducted on the data for 76 cases of IR awards announced between 2013 and 2016. 28 announcements were made of first time awards to South African companies, and 48 of second, third or fourth time awards.

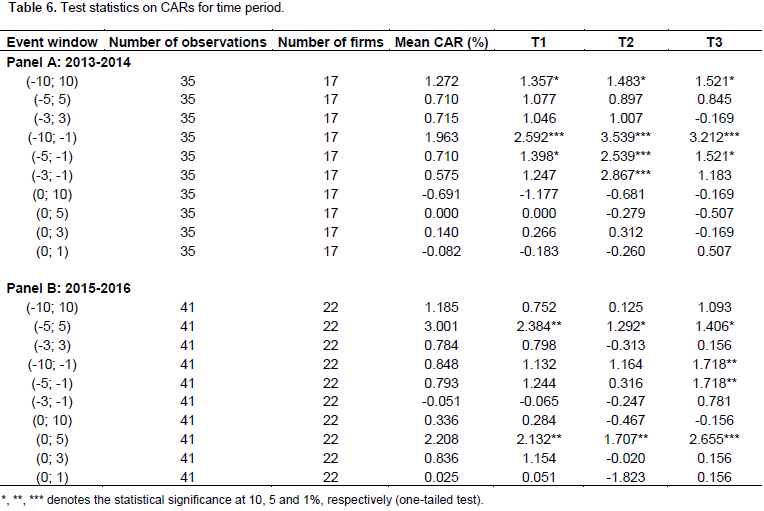

We measured the company normal returns using the market model. The CAR statistical significance is assessed using three tests (T1, T2 and T3), reported in Equations 6, 7 and 9. Furthermore, we tested whether the value attributed by shareholders to the quality of IR increased over time. For this reason, we subdivided our sample into two sub-samples: news announced 2013 to 2014 (35 observations) and 2015 to 2016 (41 observations). Focusing on the first period (Table 6, Panel A), we found positive and statistically significant average CARs of1.96, 0.71 and 1.27% in the event windows (-10; -1), (-5, -1) and (-10; 10), respectively. This probably means that at the beginning, that is, when the practice of assigning IR awards started, market participants had access to information prior to their official announcement. In 2015 to 2016, awareness of IRQ had probably grown. The study results in fact show higher statistically significant CARs compared to the previous ones (Table 6, Panel B). Positive and statistically significant mean CARs of 2.21 and 3% are found in fact in the event windows (0; 5) and (-5; 5), respectively. This means that in the period 2015 to 2016, news about IR awards was not likely to spread before the official announcement.

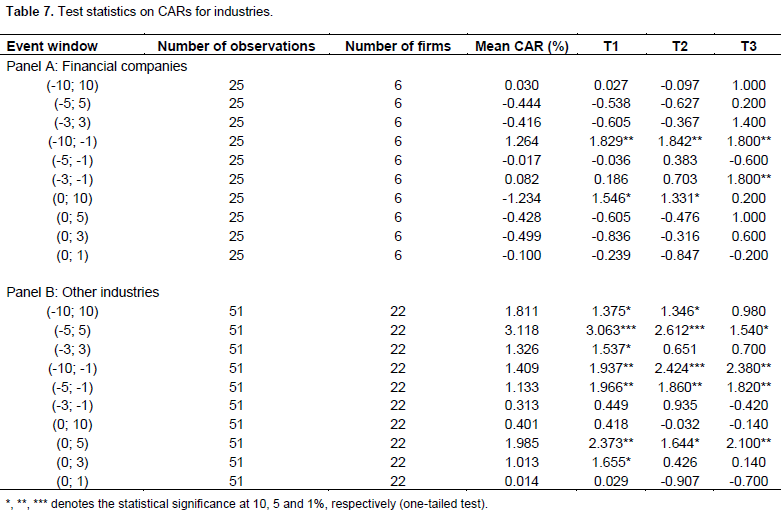

Overall, higher significant CARs in this time span are estimated in symmetric event windows. This means that shareholders took into account the good quality disclosure provided by IR in their investment assessments increasingly over time. Overall, the analysis of the two subsamples appears to confirm our hypothesis that the greater the awareness of the quality of financial and non-financial disclosure provided by the integrated report, the greater the value attributed to it (Table 6). The table shows the results of event studies conducted on the data for 76 cases of IR awards announced between 2013 and 2016. 20 news announcements were made in 2013, 15 in 2014, 19 in 2015 and 22 in 2016. We measured the company normal returns using the market model. The CAR statistical significance is assessed using three tests (T1, T2 and T3), reported in Equations 6, 7 and 9. Finally, we conducted a cross-industry study. We subdivided the study sample into two sub-samples: news about financial companies (25 observations) and non-financial companies (51 observations). Only a few announcements related to financial companies are associated with statistically significant CARs (Table 7, Panel A). Specifically, only the event window (-10; -1) shows statistically significant average CARs of 1.26%.

The study results suggest that shareholders considered the good quality disclosure provided by financial company IR as important for their investment assessments between 2013 and 2016. However, in the case of IR award announcements, this positive market effect appears limited to the 10 days before the news is officially communicated to the market. This evidence seems to confirm that in financial companies, unlike other industries, IR report culture is probably not yet strongly developed and, therefore, the quality of IR disclosure is not particularly appreciated by investors. However, we find many positive and statistically significant results for non-financial companies (Table 7, Panel B) in event windows that are symmetric (-5; 5), following (0; 5) and prior (-10; -1) and (-5; -1) to the announcement date. Higher estimations are found in the symmetric event window (-5; 5) with average CARs of 3.12%. Event windows before the day 0 (-10; -1) and -5; -1 also show average CARs of 1.41 and 1.13%, respectively. Moreover, estimated mean CARs are positive and statistically significant at 1.99% for the event window (0; 5). As suggested by Hypothesis 4, these results seem to confirm that non-financial industries are often perceived as associated with stronger environmental impacts than the financial sector and IR report culture of non-financial companies is probably more developed than that of financial companies. For this reason, the quality of non-financial IR disclosure is strongly rewarded by shareholders (Table 7). The table shows the results of event studies conducted on the data for 76 cases of IR awards announced between 2013 and 2016. 25 announcements were related to financial companies, while 51 refer to firms from other industries. We measured the company normal returns using the market model. The CAR statistical significance is assessed using three tests (T1, T2 and T3), reported in Equations 6, 7 and 9.

IR is a new reporting paradigm that encourages companies to provide a concise, holistic account of company performance based on a “multiple capitals” approach that highlights the ability of an organization to create value over the short, medium and long term. However, we still know relatively little about the market impact of IR, and its real benefits for companies have not yet been sufficiently investigated. In this context, the study aims to enrich the literature on the real value of IR. Specifically, we investigate whether shareholders, IR’s main target audience, take into account the quality of disclosure provided by IR in their investment assessments, and reward outstanding firms. We used event study methodology to measure the stock price effect of IR award announcements. The component attributed to firm-specific events is typically referred to as the ‘abnormal return’. The study results indicate that high-quality disclosure, as proxied by IR awards, has a statistically significant relationship with abnormal returns around the announcement date. The effect on prices is particularly strong in the event windows prior to the date of the announcement and is nil in the following period. This probably means that many market participants have access to information before their official announcement. Specifically, the market does not seem to be particularly interested in who wins the award, but in those companies that follow best practice when drawing up their reports, even when they are only finalists.

In the event windows before, around and after the date of the announcement, average abnormal returns are very high for finalists. This means that being a candidate for an award seems to act as a signal for the market: it is not necessary to win, you just have to be nominated! This finding is consistent with previous studies, specifically with Lee and Yeo (2016) and PwC (2014) stating that “the effort required for delivering such high-quality reporting is worthwhile”. Moreover, the “reward effect” associated with companies providing IR good quality disclosure appears to be persistent. Not only companies announcing a good ranking in an IR award competition for the first time, but also those that are finalists or winners for the second, third or fourth time, experience in fact abnormal stock returns. The study results also show that market appreciation of high-quality IR increased over the years, as suggested by Arguelles et al. (2015). This may be due to increased awareness among investors of the importance of IR (or rather the integrated thinking reflected in a well-prepared IR) and its added value. Share price increases were in fact slight during the period 2013 to 2014 and more substantial in 2015 to 2016. This implies that stakeholders probably need to develop their awareness and understanding of IR, how to use it and how it can add value. This consideration helps us to explain the next finding.

Indeed, the study final results show that the market appreciates high quality IR in all industries, although shareholder sensitivity is particularly high for non-financial companies. Traditionally, the financial sector has in fact been perceived as poorly connected to environmental impacts. For this reason, the IR report culture of non-financial companies may in fact be better developed than that of financial companies. The study highlights the importance of “pathway toward IR”, which requires the company publishes sustainability report (SR) for a preliminary period before beginning to approach IR. Such process in corporate reporting is actually more evident in non-financial companies than in financial companies. This financial “delay” is described by the recent KPMG Corporate Responsibility Report (KPMG, 2017), which shows that the financial industry is in tenth place (among a total of 15 sectors) of the world ranking on corporate reporting. The study findings thus appear to encourage managers to invest in the adoption of best practice for IR. High-quality disclosure generates a substantial positive reaction on the part of shareholders, and this is not a novelty effect as it does not fade in the first year following publication but in fact grows over time, becoming a source of value. The positive effect of high-quality IR disclosure on share prices could be interpreted in the light of the information asymmetry between companies and investors and the enhanced reputation that comes from being recognized as practice leaders or credible disclosers.

As suggested by Serafeim (2014), financial and non-financial information contained in good integrated reports probably helps to reduce information asymmetries and enables shareholders to make more efficient decisions. According to the literature, better disclosure quality could in fact affect stock returns reducing stock liquidity risk and potential investors’ estimation of risk. Stock liquidity is increased and risk is reduced by good disclosure, either because transaction costs are reduced or because demand for the stocks rises, and as a result stock returns are lower than expected (Diamond and Verrecchia, 1991; Espinosa and Trombetta, 2007). Furthermore, investors see an asset with low information as susceptible to greater systematic risk than an asset with high information (Barry and Brown, 1985; Coles et al., 1995; Clarkson et al., 1996). In the field of sustainability report studies, Guidry and Patten (2010) note that market reactions are considerably more positive for companies releasing high-quality reports than for those producing lower quality reports. This evidence confirms our conclusion that “quality matters”. A further justification of the results, that is, of the positive relationship between IR awards and stock prices, can be found in a resource-based view of the firm. Barney (1991) affirms that companies which achieve and maintain a competitive advantage tend to be rewarded with a higher stock price.

The rarity of resources that can give a competitive advantage, however, represents a serious obstacle, as the difficulty in replicating and substituting them. Such resources include intangibles like intellectual capital, organisational skills, corporate culture and reputation. IR awards and the consequent enhanced corporate reputation could be influential in this respect (Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Hosmer, 1994; Saeidi et al., 2015). IR is a new frontier of corporate reporting, and is a rich area for future research. More research is probably needed on the causes of identified relationship. We are aware that our research is limited by the fact that it covers only four years and the size of the sample is not large, but this is a structural limit: the companies selected represent in fact the universe of companies meeting the sampling criteria. Moreover, IR has a short history, and the study provides a first quantitative insight into its benefits. It would be interesting to repeat the analysis in the future in order to confirm the positive reaction of share prices to IR awards, verify the growth over time of the impact in terms of abnormal returns, and establish whether some awards generate greater effects than others on the market and why this is so, for example, by looking at the composition of the jury that assigns the prize.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adams G, McQueen G, Seawright K (1999). Revisiting the stock price impact of quality awards. Omega 27(6):595-604.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Arguelles MPM, Balatbat M, Green W (2015). Is there an early-mover market value effect for signaling adoption of integrated reporting. Unpublished working paper, University of New South Wales.

|

|

|

|

Baboukardos D, Rimmel G (2016). Value relevance of accounting information under an integrated reporting approach: A research note. J. Account. Public Policy 35(4):437-452.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Banghøj J, Plenborg T (2008). Value relevance of voluntary disclosure in the annual report, Account. Financ. 48(2):159-180.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Barney JB (1991). Firm resources and sustainable competitive advantage. J. Manage. 17(1):99-120.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Barry CB, Brown SJ (1985). Differential information and security market equilibrium. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 20(4):407-422.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Barth M E, Beaver W H, Landsman W R (2001). The relevance of the value relevance literature for financial accounting standard setting: another view. J. Account. Econ. 31(1):77-104.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Barth ME, Cahan SF, Chen L, Venter ER (2016). The economic consequences associated with integrated report quality: early evidence from a mandatory setting,

View

|

|

|

|

Bernadi C, Stark AW (2015). The transparency of environmental, social and governance disclosures, integrated reporting, and the accuracy of analyst forecasts. Unpublished working paper, Roma Tre University and University of Manchester.

|

|

|

|

Beyer A, Cohen DA, Lys TZ, Walther BR (2010). The Financial Reporting Environment: Review of the Recent Literature', J. Account. Econ. 50(2-3):296-343.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Boehmer E, Musumeci J, Poulsen A (1991). Event-study methodology under conditions of event-induced variance. J. Financ. Econ. 30:253-272.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Branco MC, Rodrigues LL (2006). Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 69 (2):111-132.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Campbell JY, Lo AW, MacKinley AC (1997). The econometrics of financial markets. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

|

|

|

|

Carnevale C, Mazzuca M, Venturini S (2012). Corporate social reporting in European banks: the effects on a firm's market value. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manage. 19:159-177.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Carnevale C, Mazzucca M (2014). Sustainability report and bank valuation: evidence from European stock markets. Bus. Ethics 23(1):69-90.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Cheng B, Ioannou I, Serafeim G (2013). Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strateg. Manage. J. 35 (1):1-23.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Clarkson P, Guedes J, Thompson R (1996). On the diversification, observability, and measurement of estimation risk. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 31(1):69-84.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Cohen JR, Holder-Webb LL, Nath L, Wood D (2012). Corporate reporting of nonfinancial leading indicators of economic performance and sustainability. Account. Horizons 26(1):65-90.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Coles JL, Loewenstein U, Suay J (1995). On equilibrium pricing under parameter uncertainty. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 30(3):347-364.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Delgado-Ceballos J, Montiel I, Raquel Antolin-Lopez R (2014). What Falls Under the Corporate Sustainability Umbrella? Definitions and Measures, Proceedings of the International Association for Business & Society 25:226-237.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

De Villiers C, Rinaldi L, Unerman J (2014). Integrated Reporting: insights, gaps and an agenda for future research. Account. Audit. Accountability J. 27(7):1042-1067.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dhaliwal D, Li O, Tsang A, Yang Y (2011). Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. Account. Rev. 86(1):59-100.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dhaliwal D, Radhakrishnan S, Tsang A, Yang Y (2012). Nonfinancial disclosure and analyst forecast accuracy: international evidence on corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure. Account. Rev. 87(3):723-759.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Diamond DW, Verrecchia RE (1991). Disclosure, liquidity, and the cost of capital. J. Financ. 46(4):1325-1359.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Doni F, Gasperini A, Pavone P (2016). Early adopters of integrated reporting: The case of the mining industry in South Africa. Afr. J. Bus. Manage. 10(9):187-208.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Easley D, O'hara M (2004). Information and the cost of capital. J. Financ. 59(4):1553-1583.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Eccles RG, Krzus MP (2010). One report: Integrated reporting for a sustainable strategy, John Wiley & Sons.

|

|

|

|

Eccles RG, Saltzman D (2011). Achieving sustainability through integrated reporting. Stanf Soc Innov Rev Summer 59.

|

|

|

|

Eccles RG, Serafeim G, Krzus MP (2011). Market interest in nonfinancial information. J. Appl. Corporate Financ. 23(4):113-127.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Eccles RG, Krzus MP (2014). The integrated reporting movement: meaning, momentum, motives, and materiality. John Wiley & Sons.

|

|

|

|

Espinosa M, Trombetta M (2007). Disclosure interactions and the cost of equity capital: evidence from the Spanish continuous market. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 34(9-10):1371-1392.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Fombrun C, Shanley M (1990). What's in a name? Reputation building and Corporate Strategy. Acad. Manage. J. 33(2):233-258.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Frías-Aceituno JV, Rodríguezâ€Ariza L, Garciaâ€Sánchez IM (2014). Explanatory factors of integrated sustainability and financial reporting. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 23(1):56-72.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Gietzmann M, Ireland J (2005). Cost of capital, strategic disclosures and accounting choice. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 32(3â€4):599-634.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

González-Benito J, González-Benito Ó (2006). A review of determinant factors of environmental proactivity. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 15(2):87-102.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2016). Forging a path to integrated reporting,

View

|

|

|

|

Griffin P, Sun Y (2013) Going green: market reaction to CSR wire news releases, J. Account. Public Policy 32(2):93-113.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Guidry RP, Patten DM (2010). Market reactions to the first-time issuance of corporate sustainability reports: evidence that quality matters. Sustainab. Account. Manage. Policy J. 1(1):33-50.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Harrington S, Shrider D (2007). All events induce variance: analyzing abnormal returns when effects vary across firms. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 42:229-256.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Healy PM, Palepu KG (2001). Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 31(1):405-440.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hendricks KB, Singhal VR (1996). Quality awards and the market value of the firm: An empirical investigation. Manage. Sci. 42(3):415-436.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hodge F, Hopkins P, Pratt J (2006). The credibility of classifying hybrid securities as liabilities or equity. Account. Organ. Soc. 31:623-634.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hope OK (2003). Disclosure practices enforcement of accounting standards, and analysts forecast accuracy: An international study. J. Account. Res. 41(2):235-272.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hoque ME (2017). Why Company Should Adopt Integrated Reporting?. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 7(1):241-248.

|

|

|

|

Hosmer LT (1994). Strategic planning as if ethics mattered. Strateg. Manage. J. 15(S2):17-34.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Huang XB, Watson L (2015). Corporate social responsibility research in accounting J. Account. Lit. 34:1-16.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) (2013a). International Integrated Reporting Framework,

View

|

|

|

|

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) (2013b). The IIRC Pilot Programme Yearbook 2013: Business and Investors Explore the Sustainability Perspective of Integrated Reporting,

View

|

|

|

|

Ioannou I, Serafeim G (2016). The consequences of mandatory corporate sustainability reporting: evidence from four countries. Working Paper No. 11-100. Harvard Business School Research,

View

|

|

|

|

Kelton AS, Pennington RR, Tuttle BM (2010). The effects of information presentation format on judgment and decision making: A review of the information systems research. J. Inf. Systems 24(2):79-105.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

KPMG (2011). Integrated Reporting, Performance Insight through Better Business Reporting,

View

|

|

|

|

KPMG (2017). The road ahead. The KPMG survey of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting 2017,

View

|

|

|

|

Lee KW, Yeo GHH (2016). The association between integrated reporting and firm valuation. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 47(4):1221-1250.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

MacKinlay AC (1997). Event studies in Economics and Finance, J. Econ. Literature 35:13-39.

|

|

|

|

Matuteâ€Vallejo J, Bravo R, Pina JM (2011). The influence of corporate social responsibility and price fairness on customer behaviour: evidence from the financial sector. Corp. Soc. Responsibility Environ. Manage. 18(6):317-331.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Merton RC (1987). A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information. J. Financ. 42(3):483-510.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mervelskemper L, Streit D (2017). Enhancing Market Valuation of ESG Performance: Is Integrated Reporting Keeping its Promise?.Bus. Strateg. Environ. 26(4):536-549.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mikkelson W, Partch M (1988). Withdrawn security offerings. J. Financ. Quantitative Anal. 23:119-133.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Milne M, Chan CC (1999). Narrative corporate social disclosures: how much of a difference do the make to investment decision making?. Brit. Account. Rev. 31:439-457.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Plumlee MA (2003). The effect of information complexity on analysts' use of that information. Account. Rev. 78(1):275-296.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Plumlee M, Brown D, Hayes R M, Marshall R S (2015). Voluntary environmental disclosure quality and firm value: Further evidence. J. Account. Public Policy 34(4):336-361.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Pope PF, McLeay SJ (2011). The European IFRS experiment: Objectives, research challenges and some early evidence. Account. Bus. Res. 4 (3):233-266.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

PwC (2014). Corporate performance: what do investors want to know? Powerful stories through Integrated Reporting,

View

|

|

|

|

Qiu Y, Shaukat A, Tharyan R (2016). Environmental and social disclosure: link with corporate financial performance. Brit. Account. Rev. 48:102-116.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Relano F, Paulet E (2012). Corporate responsibility in the banking sector: a proposed typology for the German case. Int. J. Law Manage. 54(5):379-393.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Saeidi SP, Sofian S, Saeidi P, Saeidi SP, Saaeidi SA (2015). How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, Reputation and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 68:341-350.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sarokin D, Schulkin J (1991). Environmental concerns and the business of banking. J. Commercial Bank Lending 74(5):6-19.

|

|

|

|

Scholtens B (2009). Corporate social responsibility in the international banking industry. J. Bus. Ethics 86(2):159-175.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Semenova N Hassel L (2015). On the validity of environmental performance metrics. J. Bus. Ethics 132(2):249-258.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Serafeim G (2015). Integrated Reporting ad Investor Clientele. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 27(2):34-51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sharpe WF (1963). A simplified model for portfolio analysis. Manage. Sci. 9(2):277-293.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Simpson WG, Kohers T (2002). The link between corporate social and financial performance: Evidence from the banking industry. J. Bus. Ethics 35(2):97-109.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sims CA (2006). Rational inattention: Beyond the linear-quadratic case. Am. Econ. Rev. 96(2):158-163.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Stubbs W, Higgins C, Milne M J, Hems L (2014). Financial capital providers perceptions of integrated reporting,

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Thompson P, Cowton CJ (2004). Bringing the environment into bank lending: Implications for environmental reporting. Brit. Account. Rev. 36(2):197-218.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Veldkamp LL (2006). Information markets and the comovement of asset prices. Rev. Econ. Stud. 73(3):823-845.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Verrecchia RE (1990). Information quality and discretionary disclosure. J. Account. Econ. 12(4):365-380.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Verrecchia E (2001). Essays on disclosure. J. Account. Econ. 32(1):97-180.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Viganò F, Nicolai D (2009). CSR in the European banking sector: evidence from a survey. Corporate Social Responsibility in Europe: Rhetoric and Realities, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp. 95-108.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Yongvanich K, Guthrie J (2006). An extended performance-reporting framework for social and environmental accounting. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 15(5):309-321.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Zhou S, Simnett R, Green W (2017). Does Integrated Reporting matter to the capital market? Abacus 53(1):94-132.

Crossref

|