ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to theorize a comprehensive theoretical framework for describing forward-looking information (FLI) practices of companies. The paper aims to discuss the theories usually applied to explain voluntary disclosure in literature and the interrelated theoretical perspectives regarding the role of voluntary disclosure in integrated reporting. Four relatively most common theories in disclosure literature were combined (that is agency theory, signalling theory, stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory) in a theoretical framework to interpret the key premises and the implications in disclosing FLI. The paper offers a concise template in analysing FLI for both researchers and practitioners. Moreover, it suggests some reflections on the topic and identifies possible useful paths to develop future studies of theoretical and practical relevance. The proposed framework could be valuable for producers and users of financial disclosure as its characteristics comply well with the guiding concepts developed in disclosure theories.

Key words: Forward-looking information, voluntary disclosure, theories, theoretical framework.

Modern stakeholders need increasingly sophisticated information and ask for supplementary disclosure compared to the traditional financial reporting. In addition to required disclosure, companies reveal extra data on a voluntary basis expecting that this information will probably facilitate the stock market in better identifying the driving elements of corporate value. Voluntary disclosure is a crucial element for reducing the information gap between companies and their stakeholders (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Debreceny et al., 2001; Lim et al., 2007; Hassanein and Hussainey, 2015) and many studies argued that the most important item in voluntary disclosure is forward-looking information (FLI) (Francis et al., 2008; Wang and Hussainey, 2013).

As reporting of FLI is critical for an effective communication to the market, companies are encouraged to emphasize the provision of a more forward-looking orientation of disclosure especially in their integrated reporting - IR - (IIRC, 2013). The dynamic conditions of the economic environment brought to light the deficiencies of historical information because it is not able to satisfy investors’ diversified information needs. Historical information is incapable to provide stakeholders with satisfactory insights from a forward-looking perspective. The retrospective nature of the traditional annual financial reporting is not always a reliable basis to forecast future performance. On the contrary, FLI is the type of voluntary information that allows users to know a company’s prospects and forecasts. FLI includes management’s plans, assessments of risks and opportunities, business predictions, forecasted data about the company’s operations and “the organization’s expectations about the external environment the organization is likely to face in the short, medium and long term” (IIRC, 2013). Additionally, FLI concerns financial estimates, for example anticipated cash flows, expected returns, future earnings and sale volumes (Alkhatib, 2012; Alkhatib and Marji, 2012; Uyar and Kilic, 2012a; Aljifri and Hussainey, 2007; Alkhatib, 2014). According to the ICAEW (2003), FLI involves any information that might influence the company’s subsequent financial statements and future performance (Bozzolan et al., 2009; Robert, 2010; Beyer and Die, 2012; Uyar and Kilic, 2012a, 2012b; Liu, 2015).

It is assumed that FLI would increase investors’ ability to forecast future earnings, to assess future cash flows and to make better investment decisions (Bujaki and Zéghal, 1999; Hussainey et al., 2003; Brockman and Cicon, 2013). The aim of this paper is to device a comprehensive theoretical framework for voluntary forward-looking disclosure through the integration of four most-commonly theories in literature, i.e. agency theory, signalling theory, stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory. Although prior studies use some theories to interpret findings in disclosure literature, we believe that they must be discussed in combination to offer an adequate theoretical disclosure template.

LITERATURE REVIEW ON THEORIES FOR VOLUNTARY DISCLOSURE PRACTICES AND FLI

During the past decades, empirical studies inspected accounting disclosure practices and described their rationales using numerous theoretical perspectives. Gray et al. (1995a) agree that companies release voluntary disclosure usually for traditional users (i.e. creditors, shareholders, investors, financial consultants) who use information in decision-making process. According to Healy and Palepu (2001) companies may increase their firm value by enhanced information since disclosure is an important mean to communicate firm performance to outside investors. Corporate disclosure has received a lot of attention from several researchers (Ho and Wong, 2001; Chau and Gray, 2002; Haniffa and Cooke, 2002; Eng and Mak, 2003; Akhtaruddin et al., 2009; Akhtaruddin and Haron, 2010; Hongxia and Ainian, 2008) and why companies should disclose information is stated in various theories (for example agency and signalling theory; stakeholder and legitimacy theory; resource-based theory, decision usefulness theory; institutional theory; media agenda setting theory). We offer a wide overview of the theoretical perspectives applied in disclosure literature and particularly we discuss in detail the agency theory, signalling theory, stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory.

Agency theory

Agency theory models the relationship between the shareholder (as the principal) and the management (as the agent) (Spence and Zeckhauser, 1971; Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Ross, 1979; Healy and Palepu, 2001; Lundholm and Winkle, 2006) founding on the central assumption of self-interest of individuals. Jensen and Meckling (1976) defined the agency relationship as “a contract under which one or more persons (the principals) engage another person (the agent) to perform some service on their behalf which involves delegating some decision-making authority to the agent”.

In this regard, agency theory suggests that the interests of the principal and the agent might not be aligned as both of them try to maximize their individual interests by all means. Information asymmetry is one of the main factors initiating agency problems as managers can access information more than shareholders (Brown and Hillegeist, 2007). Agency problem occurs when in a particular agency setting (or relationship) one party has an information advantage (that is private information) over another party. Hence, information asymmetry is expected to arise when the manager (the agent) possesses an information advantage over the owner (the principal) because he is directly involved in the daily operations of the firm. For example, managers may have confidential information on the company’s perspecives in order to take actions and make decisions that will mostly advantage them at the potential expense of the principal (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Fama and Jensen, 1983; Morris, 1987). As information asymmetry is believed to intensify the agency problem (Subramaniam, 2006), it is critical for shareholders to mitigate it by monitoring the agent’s opportunistic behavior or by aligning the interests between the principal and the agent.

Starting from the pioneering work of Jensen and Meckling (1976), numerous authors described disclosure strategies by agency theory. In the 1970s and 1980s academics, such as Watts (1977) and Watts and Zimmerman (1978, 1979, 1986, 1990), tried to investigate the “information perspective” of accounting information by explaining the “opportunistic perspective” of managers’ intentions to provide information. As financial statements sometimes are inadequate to reduce the agency problem, the agency theory implies that companies emphasize disclosure in order to mitigate conflicts between managers and shareholders. As Healy and Palepu (2001) and Botosan and Plumlee (2002) argued, it is probable that managers can reduce agency costs by disclosing additional (not mandated) information since outside investors have less information on firm’s performance than managers. Lundholm and Winkle (2006) stated that voluntary disclosure can be used to lessen the information asymmetry problems and agency costs (Watson et al., 2002; Barako et al., 2006). As corporate reporting regulations provide investors with the minimum quantity of information that helps them in the decision-making process (Al-Razeen and Karbhari, 2004) complete disclosure is never guaranteed even in the presence of specific rules (Al-Razeen and Karbhari, 2004). Generally, an imperfect disclosure is attributed to the conflict existing between the interests of shareholders and managers (Lev and Penman, 1990). In an unperforming market, this conflict generally happens because of an information irregularity problem that influences the voluntary disclosure policy of the company as managers don’t communicate certain information to the outside shareholders.

The reduction of information asymmetry and the related costs can be considered a significant driver for companies to disclose their FLI voluntarily. In this regard, FLI is greatly claimed by shareholders and investors for decision-making process although it is not mandatory demanded by accounting standards and rules. It is believed that the voluntary disclosure of FLI diminish information asymmetry between the principal and the agent (that is the shareholder and the management in a business setting), eliminating related agency problems and costs consequently. As argued by Singh and Van Zahan (2008) and Li et al. (2008) for voluntary intellectual capital (IC) disclosure, also FLI decreases opportunistic behaviour (for example insider trading) and lowers cost of capital by enhancing investors or creditors’ confidence on the company’s future value creation.

Signalling theory

Signalling theory regards problems related to information asymmetry. It proposes that information asymmetry should be reduced in any social setting if the party owning more information sends signals to the other interest-related party (Connelly et al., 2011). Signalling theory is applied to clarify voluntary disclosure in corporate reporting (Ross, 1977), even though it was initially developed to explain the information asymmetry in the labour market (Spence, 1973). Due to the information asymmetry issue, companies signal particular information to attract investments in the market and to enhance a positive reputation (Verrecchia, 1983). Signalling theory is valuable for analyzing disclosure behaviour when two parties (organisations or individuals) have different information. Usually, one party (that is the sender) must decide whether and how to communicate (or signal) the information, and the other party (that is the receiver) must decide how to interpret the signal. A signal is an observable action (or structure) which is utilized to show the concealed characteristics (or quality) of the signaller (Salama et al., 2010). The assumption of the theory is that the sending of a signal is favourable to the signaller (for example to specify the high quality of its products compared with those of competitors).

On one hand, a company could attract investment and consequently could decrease the costs of raising capital thanks to the favour of various stakeholders. On the other hand, signalling would help stakeholders (especially investors) to better check the value of the company and then to make more favourable decisions (Whiting and Miller, 2008). This clarifies why companies are stimulated to disclose voluntarily more information than the mandatory ones required by laws and regulations (Campbell et al., 2001), that is to appear positively in the market (Spence, 1973; Connelly et al., 2011).

As expressed in signalling theory, companies have several means to signal information about themselves. In this regard, corporate disclosure can be a signal to capital markets as managers can use voluntary disclosure for attracting new investment and enhancing their reputation among investors (Watts and Zimmerman, 1978; Ross, 1979; Campbell, 2000; Watson et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2004). In this regard, especially voluntary FLI is a powerful signalling mean to the advantage of a firm (for example enhancing corporate image and the relationships with various stakeholders, interesting potential investors, decreasing capital costs and lowering volatility of stocks).

Stakeholder theory

The stakeholder theory involves the relations between the organization and all the numerous groups who have an interest in it (Roberts, 1992; Gray et al., 1996; Deegan, 2006). A company is regarded to be part of a wide social system in which it operates and it could be positively accountable to various stakeholders. From a stakeholder perspective, an organization should effort to meet different goals of a varied range of stakeholders rather than those of shareholders merely (Freeman, 1984; Roberts, 1992). Stakeholder theory is founded on the idea that the closer the companies’ relationships are with other interest parties, the easier it will be the achievement of its business objectives. Hence, stakeholder theory is a system oriented theory (Alam, 2006) because it asserts that company’s activities should be adjusted to gain stakeholders’ approval (Gray et al., 1995a,b). As Guthrie et al. (2006) stated: “According to stakeholder theory, an organization’s management is expected to undertake activities deemed important by their stakeholders and to report on those activities back to the stakeholders […] stakeholder theory highlights organizational accountability beyond simple economic or financial performance”.

Freeman (1984) defined a stakeholder as follows: any individual or group who can affect, or be affected by, the attainment of firm’s objectives. The category of stakeholders typically includes shareholders, employees, suppliers, customers, competitors, creditors, investors as well as groups representing the media, government and communities, consumer advocates and environmentalists (Clarkson, 1995).

Stakeholder theory often relates to the term “accountability” which is defined by Mulgan (1997) as the responsibility of one party to another within a relationship where one party entrusts another with the performance of certain responsibilities. From an accounting perspective, accountability deals with the duty of an organization to disclose information concerning its performance, financial position, investments and compliance in order to support users in making proper decisions. An organization should be accountable to all stakeholders within a stakeholder perspective even though the organization merely needs to discharge accountability merely to its shareholders according to a traditional view.

Disclosure is an essential mean for organizations to discharge their accountability and many categories of corporate reporting have established from the adoption of a stakeholder orientation. For example, Vergauwen and Alem (2005), Guthrie et al. (2006), Whiting and Miller (2008) and Schneider and Samkin (2008) applied stakeholder theory or some notions of it to interpret the voluntary intellectual capital (IC) disclosure of organizations. From a stakeholder perspective, corporate disclosure advantages the relationship between a company and its stakeholders (Gray et al., 1995a) and in this regard, disclosure can be considered a “strategy for managing, or perhaps manipulating, the demands of particular groups” (Deegan and Blomquist, 2006). In this regard, FLI is increasingly claimed by various stakeholders (Vergauwen and Alem, 2005; Tayles et al., 2007) but companies are not responding as stakeholder theory might expect they would in disclosing voluntary FLI. It can be estimated that voluntary disclosure on FLI reduces information asymmetry between the company and its stakeholders improving the relationships between them. Consequently, valuable FLI reinforces relations between companies and external stakeholders, especially powerful ones. According to Gray et al. (1996) and Deegan and Samkin (2008), a virtuous relationship between the company and its numerous stakeholders could gain approval and support from them or distract their opposition and disapproval (for example loyalty of customers) allowing companies to succeed and survive in a sustainable manner.

Legitimacy theory and FLI

Legitimacy theory concerns with the relationship between the organization and society at large and it postulates that a company exists if its values match with that of the society where it operates (Dowling and Pfeffer, 1975; Lindblom, 1994; Wartick and Mahon, 1994; Magness, 2006). Legitimacy theory assumes that organizations should constantly ensure that their operations abide by norms of their respective communities so as to be perceived as “legitimate” by various stakeholders in society (Deegan and Samkin, 2008; Guthrie et al., 2006). The status of legitimacy is crucial for the survival of organizations within a wide societal system including both stakeholders and non-stakeholders (Woodward et al., 1996; Bushman and Landsman, 2010). Unlike stakeholder theory, legitimacy theory focuses on the interactions between firm and society (Ulmann, 1985) and suggests that there is a “social contract” (Shocker and Sethi, 1974) between the organization and the community in which it operates to assurance a state of organizational legitimacy (Deegan, 2006; Magness, 2006; Deegan and Samkin, 2008). Under the social contract, a company should operate within the norms and expectations of the society at large, rather than within those of investors’ merely. However, it is not satisfactory for an organization to run within social contract only. It also ensures that its activities are perceived to be adequate with the societal expectations of various groups of stakeholders signalling its legitimacy (from the perspective of signalling theory).

Dowling and Pfeffer (1975) provided a useful description of organisational legitimacy, thus: “Organisations seek to establish congruence between the social values associated with or implied by their activities and the norms of acceptable behaviour in the larger social system of which they are a part. Insofar as these two value systems are congruent, we can speak of organisational legitimacy. When an actual or potential disparity exists between the two value systems, there will be a threat to organisational legitimacy”.

It is acknowledged that managers can have dissimilar perceptions on legitimacy, and consequently they may implement mixed strategies to attain the state of legitimacy. In order to bridge the legitimacy gap, an organization must recognize those activities that are within its control and the relevant publics that have the power to foster legitimacy (Neu et al., 1998; Bushman and Landsman, 2010). As showed by Lindblom (1994) and Dowling and Pfeffer, (1975), voluntary disclosure would be a real mean to realize legitimacy. Prior literature debated corporate disclosure practices within the theoretical framework of legitimacy theory (Patten, 1992; Tilt, 1994; Wilmshurst and Frost, 2000; Deegan, 2002) and in this regard Dowling and Pfeffer (1975) suggested that legitimacy theory provides valuable insights concerning corporate disclosure behaviour. According to Deegan (2002), one of the many possible motivations of disclosure is the ambition to legitimise organisation’s operations. Since the legitimacy theory is based on the social perception, management is enforced to report information that would uprate the external users’ opinion about its organization (Cormier and Gordon, 2001; Linthicum et al., 2010).

Legitimisation can satisfy both through mandatory disclosures reported in financial statements and voluntary disclosures included in other sections of financial reporting and/or in integrated reporting (Magness, 2006; Lightstone and Driscoll, 2008; Thornburg and Roberts, 2008; Shehata, 2014). Previous corporate disclosure studies on legitimacy theory argued that its use is a useful theoretical framework for inspecting and clarifying variations in disclosure practices. Although financial statements have been perceived as an important source of legitimation in literature (Dyball, 1998; Deegan, 2002; Lopes and Rodrigues, 2007), legitimation theory can be applied to disclose additional information than what it has currently been provided for in the extant literature (Patten, 1992; Adams et al., 1998; Brown and Deegan, 1999; O’Donovan, 2002). From the viewpoint of legitimacy theory, companies should voluntarily disclose information that is expected by society since the compliance of societal expectations could foster continued inflows of capital (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978). Agreeing with this perspective, organizations may benefit from reporting FLI on a voluntary basis, perhaps in the integrated reporting, in order to be compliant with societal expectations or to deflect the attention of the community (or media) from the principal negative effects of the organization’s activities (Deegan, 2006).

THE IDEA OF AN INTEGRATED THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The construction of an integrated theoretical framework based on the above-mentioned four theories implies the integration of key concepts which are reliable in explaining voluntary FLI. For this purpose, we look at the relationships between the four theories’ insights as a basis for disclosing voluntary FLI.

Integration of theories in explaining FLI

Information asymmetry is the main concept of agency theory and it can be considered the most relevant one in relation to voluntary disclosure of FLI. Even in an efficient capital market, managers have more information on firms’ future performance than stakeholders (especially, investors). Hence, the agency problem appears unless both parties share the matching interests completely. In this regard, voluntary disclosure is a mean for moderating the agency problem and in particular, voluntary FLI can reduce information asymmetry between management and shareholders. Also signalling theory proposes some possibly effective answers to the information asymmetry problem, that is managers can positively put forward company’s results through the voluntary disclosure of FLI as a signal. In particular, the use of FLI - as a signal – could attract potential investors, decrease volatility of stocks, lower capital costs, improve corporate image, further a better knowledge of future performance and mainly could develop the relationships with numerous stakeholders. Consequently, from a stakeholder perspective, we argue that voluntary FLI can decrease information asymmetry between a company and its stakeholders improving the relationship between them.

We integrated the disclosure theories to explain voluntary disclosure practices of FLI. Accordingly, signalling theory and legitimacy theory can be considered complementary in clarifying voluntary FLI disclosure practices of companies. Hence, organizations report FLI on a voluntary basis in order to signal that they comply with societal expectations and norms (or the social contract). This is a two-way relation between the organization and society in contrast with stakeholder theory that gives emphasis on the one-way provision of organizational accountability to stakeholders in society. Stakeholder theory assumes that some groups are more influential than others within the society while legitimacy theory devises society as a whole (Woodward et al., 1996). Despite this difference, some concepts within legitimacy theory are in line with those of stakeholder theory in relation to voluntary FLI disclosure. Compared to stakeholder theory, legitimacy theory plays a more helpful role in explaining voluntary FLI as a mean for companies to gain and uphold the status of legitimacy in society and to discharge their accountability to various stakeholders. Accordingly, it can be supposed that an organization discloses FLI voluntarily to lessen information asymmetry and to discharge accountability to various stakeholders, as well as to signal its legitimacy and excellence to society. Table 1 summarizes the main concepts of the theories and the interrelated premises in explaining voluntary FLI disclosure practices. It is assumed that the alternative disclosure theories focus upon dissimilar perspectives of the same issue.

Based on the relationships debated overhead, the theories are related and reinforce each other in explaining the voluntary disclosure practice of FLI (Figure 1). Our framework offers a range of disclosure strategies by which FLI can be disclosed according to the key concepts of the theories. For the objective of this research, the interconnected concepts of the theories were integrated with four key premises explaining voluntary FLI disclosure as follows:

Going beyond historical financial reporting

Organizations report FLI on a voluntary basis to signal that they comply with societal expectations and norms. To mitigate the legitimacy gaps, organization can try to change its disclosure behavior offering a balanced and clear discussion of factors and trends likely to impact future prospects rather than continuing to rely on historical information only. Henceforth, assumed the growing demand for a forward-looking orientation of companies’ reporting, a diverse approach will be called for since very few companies are close to provide the extent of information expected by stakeholders.

Putting concern into perspective

FLI plays a positive role in discharging organizational accountability to numerous stakeholders within societal expectations and norms. Voluntary FLI advantages companies to assurance legitimacy in society as organizations should ensure their operations comply with societal expectations. The value of delivering a clear forward-looking picture of the company is based on the potential disclosure has to challenge external perceptions and stakeholders’ demands for a forward-looking orientation of reporting. Consistent with these considerations, managers are likely to disclosure FLI to increase the interest-related parties’ confidence on the company’s future performance (Singhvi and Desai, 1971). By resorting to voluntary FLI, companies are perceived to be legitimate by society as they provide insights into the sustainability of the business and enhance investors to put financial performance into perspective.

Giving stakeholders what they need about the future

FLI can decrease information asymmetry between the company and various stakeholders by giving them what they need about the future. Forward-looking information can be delivered considering a comprehensive picture of the company (as revealed by contextual information) and a specific reference to profits. Non-financial indicators of performance can be used as drivers of future perspectives providing investors with appreciated insights on which to found their investment. Targets for these non-financial drivers can also be important aspects of FLI as they allow to communicate the companies’ perspectives to the market without limiting information into the realms of profit forecasts. The ever increasing demand for FLI has come up several frequently-voiced concerns among organizations. Nevertheless, concerns do not have to raised on whether communicating about future prospects consists in providing profit forecasts (with the potential for short-term pressure to realize those forecasts) rather than focusing on value delivery. As suggested by Hussainey et al. (2003); Hussainey and Walker (2009) and Athanasakou and Hussainey (2014), FLI develops investors’ ability to forecast future earnings.

Communicate key operating and performance perspectives

The disclosure of FLI as a voluntary signal is a possibly effective solution to solve the information asymmetry problem. The provision of a forward-looking orientation of disclosure allows identifying and communicating factors and trends related to investors’ assessments of future business performance. Relevant factors could be those likely to influence a company’s future position, development and performance. These might comprise the expected expansion of new products and services, current and intended amount of investment expenditure and clear descriptions of how that expenditure will be utilized to reach business objectives. However, there are no specific rules fixing up what FLI a company must offer in integrated reporting. Disclosure concerning an organization’s future performance is generally report on a voluntary basis according to managerial discretion (Clarkson et al., 2008). Companies can decide which information to leave out and which to include according to the industry sectors in which they operate and their own distinctive business dynamics.

We constructed a template for analysing managers’ reporting on FLI and related disclosure decisions in a capital markets setting. Figure 1 illustrates the construction of the framework concerning voluntary disclosure of FLI and shows how the key concepts of the theories are integrated with the disclosure premises of FLI. Through the distinct assumptions completed and standpoints assumed, the framework paints the picture of voluntary FLI in diverse shades, offering different insights into the subject matter.

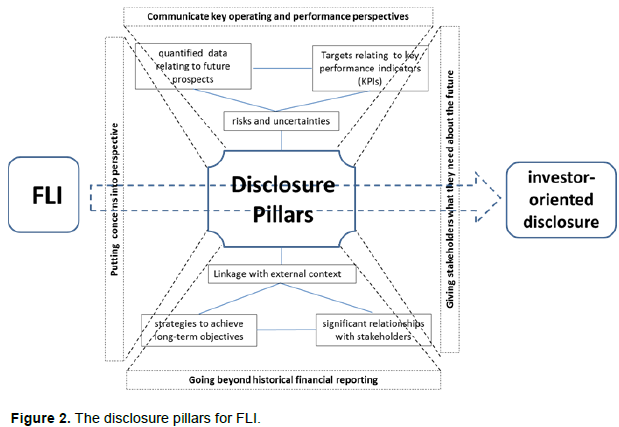

Pillars for effective disclosure on FLI

An organization’s reporting can be defined as “investor-oriented” if it provides investors with decision-relevant information that allows them to assess the amounts of future cash flows and risks from a predictive perspective. There are two kinds of predictive value of information: direct predictive value if information offers straightforward evidence about expectations about future cash flows; indirect predictive value which relates to the effectiveness of information acting as an indicator for that stream of interests. By considering the following pillars, companies provide investors with a forward-looking orientation (predictive value) of disclosure increasingly demanded in reporting.

Explain strategies to achieve long-term objectives

A key objective of reporting is to help investors in judging the adopted strategies and their potential to be successful. The description of the company’s principal resources (both tangible and intangible) and how they will be employed in performing strategies is a key pillar in disclosing FLI. The description of the resources currently available to attain the long-term objectives and how a company expects them going forward provides valuable insights into the commitment to strategies and future prospects. Good disclosure practice would share the progress that has been achieved towards long-term business objectives and encourage the inclusion of information on future targets in integrated reports.

Define the main risks and uncertainties that may affect the company’s long-term prospects

An explanation of the main risks and uncertainties is a crucial issue to achieve a forward-looking orientation in disclosure. Defining a general list of all the risks fronting companies in an industry (for example strategic risks, financial risks, operational risks, reputational risks, compliance risks, other risks) fails to reflect the company’s particular risky circumstances within the changing external environment and how the risks are and will be managed. Effective reporting of risk should set out how the company recognizes its major risks, whether the amount of risk (or opportunity) is increasing or decreasing and the approach to mitigate them also in the future. Hence, through a voluntary disclosure of FLI, an integrated reporting should reply to the following question: “what uncertainties and challenges is a company likely to meet in pursuing its strategy, and what are the possible implications for its business model and future performance?”.

Explain the significant relationships with stakeholders that may influence the performance of the company and its value

The behaviour of the stakeholders (from suppliers and customers to regulators) can have a significant effect on the company’s future prospects. Therefore, clarifying which stakeholders are important for the company is a critical feature of effectual FLI. The company should go into more details of engagement with stakeholders, recognizing its customers as key stakeholders for the company’s business success and elucidating why investors should assess corporate social responsibility as essential for the success of the company. Further, the company should describe the methods used (customer satisfaction surveys, for example online surveys, e-mail surveys, face to face interviews, telephone interviews) to measure customer satisfaction (or/and dissatisfaction) and the initiatives for increasing it in the future.

Provide quantified data on trends and factors expected to affect the company’s future prospects

Companies should go on to quantify corporate prospects and the possible impact of operations on future income. The analysis of current and expected development of the business, performance and position of the company needs the examination of relevant contextual information, such as the identification of proper trends and factors influencing the business, how they are coped with and how success is measured (by means of quantifiable data, for example revenue growth, earnings per share, ROE, market share, total stakeholder return, customer service, retaining customers). This disclosure path also consists in providing information about trends and factors characterizing historic performance and likely to impact on future performance.

Communicate targets of key performance indicators (KPIs) applied to manage business

It is by showing specifically the key performance indicators (KPIs) used in managing the business that investors are able to evaluate the likelihood of the strategy to succeed. A minimal narrative description of the key resources, risks and relationships that are fundamental to the successful application of the strategies is not enough. For each KPI, information on trends should be provided, including information for the current and future years, as well as quantifications and/or commentaries of future targets. In forming a view on what to report, companies should also consider whether robust, quantifiable financial and non-financial KPIs are available to support what should be disclosed.

Alignment and linkage with external context

It is essential to communicate how the external environment will affect the organization and how management of resources, risks and relationships will support the achievement of strategies and longer-term objectives. The disclosure of social and environmental FLI is a strategic tool in achieving organisational goals and in influencing the outlooks of external stakeholders (Guthrie and Parker, 1990). A forward-looking orientation of disclosure is beneficial to investors in identifying the market in which the company is likely to operate in the future years and the potential success of the company’s future strategies within it. An integrated report ordinarily should highlight expected changes over time and build on transparent and complete analysis about the external environment the organization could face in the short, medium and long term. Companies would include some commentaries on the market in which they operate and provide an emphasis on future growth opportunities and business strategies. Accordingly, by explaining how corporate responsibility can impact on future decisions and sustainability, the company arranges for a well understanding of the risks related to these activities and the implications for future financial performance. Figure 2 summarizes the pillars for effective voluntary FLI disclosure practices.

The framework states six pillars (guiding principles) explaining voluntary disclosure practices on FLI. The six pillars should not be considered separately as each one embodies a logical building block for useful reporting on the future. The challenges of companies are to report their view on the future through all pillars that are applicable for their business, thereby indicating a forward-looking orientation in a coherent and consistent way. Hence, the six pillars can be viewed as incentives for voluntary FLI disclosure. By disclosing FLI, an organization is more likely to satisfy stakeholders’ needs and expand its reputation for transparency, reliability and credibility. As reputation is a firm-specific, intangible and non-tradable resource (that is difficult to replicate), voluntary FLI is regarded as a strategic initiative to encourage good relationships with stakeholders and to raise the success of a company. In this regard, Freeman (1984) claimed that it is very difficult for a company to maximize long-term value if it does not maintain virtuous relationships with stakeholders by disregarding their information needs.

POSSIBLE IMPLICATIONS AND LIMITATIONS OF THE FRAMEWORK

Developments in voluntary disclosure have significant implications for organizations. At a general theoretical perspective, the focus on FLI has implications for understanding the dynamic process of progressively complex disclosure practices (in integrated reporting) in order to gain legitimacy in heterogeneous and pluralistic environments. Usually, in cases of incompatible disclosure demands, still little is acknowledged concerning the micro-level procedures of how organizations reply to opposing institutional pressures and thus, how they seek to establish legitimacy (Suddaby and Greenwood, 2005). The framework underlines that legitimacy is not just about audience assessment and subsequent alignment or compliance-focused strategies. The importance of the framework lies on its valuation of corporate disclosure as a response to the current demands of stakeholders and on the way it perceives voluntary FLI and its social impact to answer to government or public pressure for information (Guthrie and Parker, 1989, 1990). The template also shows that a forward-looking orientation of disclosure is subjected to several demands and/or valuations from a plurality of stakeholders. The organisational vision of voluntary FLI should be investor-oriented putting into action a more dynamic and stable “dialogue” among players in the field. Increased voluntary FLI is expected to have a significant effect on both the quality and the quantity of publicly available information and therefore it is valued to reduce uncertainty from an investor’s perspective.

Where corporate management must reinforce or reinstitute a relationship of trust with stakeholders, voluntarily disclosure of FLI could be a viable way to increase managerial credibility and transparency of reporting. Any management team that goes beyond the bounds of legal requirements by reporting significant additional FLI in a voluntary basis is likely to considerably improve its credibility among investors. Furthermore, disclosing information about well-thought-out strategies should facilitate investors to realize a better appreciation of management’s purposes as well as to understand the firm’s future value-creating prospective and earnings forecasts. Long-term investors could be more inclined to invest on companies with high amount of disclosure in order to minimize their investment risk. Better knowledge about the opportunities and challenges of firms helps investors to take a longer-term perspective on their capital-allocation decisions and on their assessment of risk-adjusted returns. For example, companies can give information about their key assets and how they manage them to achieve long-term growth in shareholder value. In addition, from a macroeconomic perspective, FLI should support the market in its role as a capital allocation mechanism since any development in disclosure has the potential to reduce stock price volatility, to lower risk premium and to upgrade the company’s ability to attract additional capital.

However, there is the likelihood that amplified disclosure may lead to excessive information from an investor perspective and any such result could disprove some of the benefits debated above. Increased disclosure may decrease a company’s competitive advantage just because additional information is exposed to competitors. This has raised some concerns amongst companies. Some fear that FLI could undermine competitive advantage as increasing demand for voluntary FLI could force companies to disclose competitively-sensitive information, to expose themselves to the threat of litigation or to make profit forecasts. Therefore, companies need to understand what the demand for voluntarily FLI really means. Without such an understanding, management could take fright at the call for FLI, sheltering in bland information that provides no benefits to investors or to the companies themselves. Managers may simply release general statements about the future revealing little and just adding noise to the reporting process. Hence, the demand for voluntary disclosure will imply a number of risks for organizations that fail to prepare sufficiently for its implementation. Nevertheless, voluntary FLI should bring real business benefits, enhanced business understanding, improved relationships with key stakeholders, heightened efficiencies resulting from the appropriate alignment of reporting and communication strategies, governance and board effectiveness. Companies need to approach voluntary FLI with the right mindset. There are certain information which could challenge company’s market position but this condition should not be detained as a convenient smokescreen for avoiding forthright and full disclosure of FLI. A balancing perspective between disclosing (“what are we going to report?”) and withholding (“what should we withhold?”) FLI needs to be a realistic process.

This study offers a conceptual framework for voluntary disclosure of FLI through the integration of four disclosure theories, that is agency theory, signalling theory, stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory. The fashioned theoretical framework includes four interconnected concepts and six disclosure pillars which can be considered corporate motivations for effective communication of future perspectives.

The paper widely analyzes the theoretical perspectives reviewed in disclosure literature to enquire how the theories explain managers’ reporting and disclosure decisions in this area. According to agency theory, information asymmetry occurs in most business settings where the management of a company has an information advantage over the shareholders. Closely related to agency theory, signalling theory proposes that information asymmetry should be abridged if the party possessing more information sends signals to the other interest-related parties. In this regard, corporate voluntary disclosure can be a signal to attract new investments in capital markets. Stakeholder theory includes the concept of “shareholder” within agency theory in the broader context of “stakeholder” and it contends that companies should discharge accountability to various groups of stakeholders in the society. Legitimacy theory develops the stakeholder theory further suggesting that companies need to fulfill norms and societal expectations. Hence, it can be presumed that companies disclose FLI voluntarily to minimize information asymmetry, to discharge accountability towards numerous stakeholders and to signal their legitimacy and superiority. Based on the relationships between the mentioned disclosure theories, key concepts are interrelated and support each other with four key premises explaining voluntary FLI disclosure practices. Hence, we constructed a comprehensive theoretical framework which states six pillars (guiding principles) for an effective voluntary FLI disclosure.

The motivations of our study are twofold. First, we are motivated by the amplified importance of FLI in corporate disclosure and by search for a better knowledge of the theoretical underpinnings of a forward-looking perspective in integrated reporting. Our study is particularly beneficial in showing the how voluntary FLI can help to develop a strong positive relationship with stakeholders as disclosure is sought keenly by companies to meet investors’ information needs. Second, we are inspired by calls for theoretical developments in research on FLI. In this regard, we developed a theoretical framework for voluntary FLI by advancing some primary perspectives within a conceptual model.

It is accepted that the constructed framework has a number of limitations. Firstly, the framework overlooks some other theoretical perspectives that are appropriate in explaining voluntary FLI disclosure, such as institutional theory (Petty and Cuganesan, 2005) and media agenda-setting theory (Sujan and Abeysekera, 2007). Additionally, the framework does not recognize the costs for voluntary disclosure of FLI (for example competition and political costs), which also influence the disclosure of voluntary FLI. Finally, the framework is not supported by any empirical evidence so that it ignores other practical perspectives which can be relevant for voluntary disclosure. Even though the fashioned framework has some limitations, we believe that this research could develop more in-depth explorations in future research regarding theoretical perspectives on voluntary FLI (that is combining additional theories into the framework and/or employing it in various contexts). The conceptual framework creates the possibility for a practical tool as there are some potential applications of it in future research. For instance, it can be applied as a theoretical template to interpret disclosure practices of firms in a particular country or industry. For instance, a researcher could interpret this framework within the specific background of a country or industry to examine why organizations would like to report FLI (or some topics of FLI) on a voluntary basis. This study makes two contributions to the existing literature. First, the paper adds to the prior disclosure literature concerning FLI since no prior studies have attempted to design a theoretical framework on voluntary forward-looking disclosure. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first academic paper that provides a coherent framework on FLI, with an explanatory template. Second, the framework can be used as a theoretical basis for future empirical studies investigating the drivers (or perceptions) of voluntary forward-looking disclosure. The paper provides the growing number of academic researchers in this area with comprehensive insights upon which they can build their research. The study also offers practical implications mainly for preparers of IR, managers and regulators (for example IIRC) since it inspires further efforts to disclose FLI and to offer a voluntary forward-looking disclosure perceived as “informative” by stakeholders. Academics could employ this paper for studying empirical voluntary forward-looking disclosure and practitioners for better understanding organizations’ behaviours towards decreased or increased voluntary FLI.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adams CA, Hill WY, Roperts CB (1998). Corporate social reporting practices in western Europe: legitimating corporate behavious. The British Accounting Review 30(1):1-21.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Akhtaruddin M, Haron H (2010). Board ownership, audit committees' effectiveness and corporate voluntary disclosure. Asian Review of Accounting 18(1):68-82.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Akhtaruddin M, Hossain MA, Hossain M, Yao L (2009). Corporate Governance and Voluntary Disclosure in Corporate Annual Reports of Malaysian Listed Firms. The Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research 7(1):1-20.

|

|

|

|

|

Alam M (2006). Stakeholder Theory. In. Hoque Z (eds.), Methodological Issues in Accounting Research: Theories and Methods. London, Spiramus Press. pp. 207-222.

|

|

|

|

|

Aljifri K, Hussainey K (2007). The determinants of forward-looking information in annual reports of UAE companies. Managerial Auditing Journal 22(9):881-894.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Alkhatib K (2012). The Determinants of Leverage of Listed Companies. International Journal of Business and Social Sciences 3(24):78-83.

|

|

|

|

|

Alkhatib K (2014). The determinants of forward-looking information disclosure. Social and Behavioral Sciences 109(8):858-864.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Alkhatib K, Marji Q (2012). Audit reports timeliness: Empirical evidence from Jordan. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences Journal 62:1342-1349.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Razeen A, Karbhari Y (2004). Ineaction between compulsory and voluntary disclosure in Saudi Arabian corporate annual reports. Managerial Auditing Journal 19(3):351-360.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Athanasakou V, Hussainey K (2014). The perceived credibility of forward-looking performance disclosures. Accounting and Business Research 44(3):227-259.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Barako DG, Hancock P, Izan H (2006). Factors influencing voluntary corporate disclosure by Kenyan companies. Corporate Governance: An international Review 14(2):107-125.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Beyer A, Dye RA (2012). Reputation management and the disclosure of earnings forecasts. Review of Accounting Studies 17(4):877-912.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Botosan CA, Plumlee MA (2002). A re-Examination of Disclosure Level and the Expected Cost of Equity Capital. Journal of Accounting Research 20(1):21-40.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bozzolan S, Trombetta M, Beretta S (2009). Forward looking disclosure and analysts' forecasts: a study of cross-listed European Firms. European Accounting Review 18(3):435-473.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Brockman P, Cicon J (2013). The information content of management earnings forecasts: An analysis of hard versus soft information. Journal of Financial Research 36(2):147-173.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Brown N, Deegan C (1999). The public disclosure of environmental performance information – a dual test of media agenda setting theory and legitimacy theory. Accounting and Business Research 29(1):21-41.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Brown S, Hillegeist SA (2007). How disclosure quality affects the level of information asymmetry. Review of Accounting Studies 12(2-3):443-477.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bujaki ML, Zéghal D (1999). The disclosure of future oriented information in annual reports of Canadian corporations.

|

|

|

|

|

Bushman R, Landsman WR (2010). The pros and cons of regulating corporate reporting: a critical review of the arguments. Accounting and Business Research 40(3):259-273.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Campbell DJ (2000). Legitimacy theory or managerial reality construction? Corporate social disclosure in Marks and Spencer PLC corporate reports, 1969-1997. Accounting Forum 24(1):80-100.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Campbell D, Shrives P, Saager HB (2001). Voluntary disclosure of mission statements in corporate annual reports: signaling what and to whom?. Business and Society Review 40(3):259-273.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chau GK, Gray SJ (2002). Ownership structure and corporate voluntary disclosure in Hong Kong and Singapore. The International Journal of Accounting 37(2):247-264.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Clarkson MBE (1995). A stakeholder framework of analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review 20(1):92-117.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Clarkson PM, Li Y, Richardson GD, Vasvari FP (2008). Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: an empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society 33(4):303-327.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Connelly BL, Certo ST, Ireland RD, Reutzel CR (2011). Signalling theory: a review and assessment. Journal of Management 37(1):39-67.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cormier D, Gordon I (2001). An examination of social and environmental reporting strategies. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 14(5):587-616.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Debreceny R, Gray GL, Rahman A (2002). The determinants of Internet financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 21(4-5):371-394.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Deegan C (2002). Introduction: the legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures – a theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(3):282-311.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Deegan C (2006). Legitimacy theory. In: Hoque Z (eds.), Methodological Issues in Accounting Research: Theories and Methods. London, Spiramus Press. pp. 161-181.

|

|

|

|

|

Deegan C, Blomquist C (2006). Stakeholder influence on corporate reporting: An exploration of the interaction between WWF-Australia amd the Australian minerals industry. Accounting Organizations and Society 31(4-5):343-372.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Deegan CM, Samkin G (2009). New Zealand financial accounting. McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

|

|

|

|

|

Dowling J, Pfeffer J (1975). Organizational legitimacy: social values and organisational behaviour. Pacific Sociological Review 18(1):122-136.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dyball M (1998). Corporate annual reports as promotional tools: the case of Australian national industries limited. Asian Review of Accounting 6(2):25-53.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eng LL, Mak YT (2003). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 22(4):325-345.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fama E, Jensen M (1983). Agency problems and residual claims. The Journal of Law and Economics 26(2): 327-349.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Francis J, Huang AH, Rajgopal S, Zang AY (2008). CEO reputation and earnings quality. Contemporary Accounting Research 25(1):109-147.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Freeman RE (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston, Pitman, MA.

|

|

|

|

|

Gray R, Kouhy R, Lavers S (1995a). Corporate social and environmental reporting a review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 8(2):47-77.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gray R, Kouhy R, Lavers S (1995b). Methodological themes: constructing a research database of social and environmental reporting by UK companies. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 8(2):78-101.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gray R, Owen D, Adams C (1996). Accounting and Accountability: Changes in Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting, London, Prentice Hall.

|

|

|

|

|

Guthrie J, Parker L (1989). Corporate social reporting a rebuttal of legitimacy theory. Accounting and Business Research 19(76):343-352.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Guthrie J, Parker L (1990). Corporate social disclosure praxtice: a comparative international analysis. Advances in Public Interest Accounting 3(2):159-173.

|

|

|

|

|

Guthrie J, Petty R, Ricceri F (2006). The voluntary reporting ofintellectual capital: comparing evidence from Hong Kong and Australia. Journal of Intellectual Capital 7(2):254-271.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Haniffa RM, Cooke TE (2002). Culture, corporate governance and disclosure in Malaysian corporations. Abacus 38(2):317-350.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hassanein A, Hussainey K (2015). Is forward-looking financial disclosure really informative? Evidence from UK narrative statements. International Review of Financial Analysis 41:52-61.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Healy PM, Palepu KG (2001). Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics 3181-39:405-440.

|

|

|

|

|

Ho SSM, Wong KS (2001). A study of corporate disclosure practices and effectiveness in Hong Kong. Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting 12(1):75-101.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hongxia L, Ainian Q (2008). Impact of Corporate Governance on Voluntary Disclosure in Chinese Listed Companies. Corporate Ownership and Control 5(2):260-366.

|

|

|

|

|

Hussainey K, Walker M (2009). The effects of voluntary disclosure and dividend propensity on proces leading earnings. Accounting and Business Research 39(1):37-55.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hussainey K, Schleicher T, Walker M (2003). Undertaking large-scale disclosure studies when AIMR-FAF ratings are not available: the case of prices leading earnings. Accounting Business Research, 33(4):275-294.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) (2003). New reporting models for business. Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, London.

|

|

|

|

|

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) (2013). The International IR Framework.

|

|

|

|

|

Jensen MC, Meckling W (1976). Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3(4):305-360.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lev B, Penman SH (1990). Voluntary forecast disclosure, non disclosure and stock prices. Journal of Accounting Research 28(1):49-76.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Li J, Pike R, Haniffa R (2008). Intellectual capital disclosure and corporate governance structure in UK firms. Accounting and Business Research 38(2):137-159.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lim S, Matolcsy Z, Chow D (2007). The association between Board Composition and Different Types of Voluntary Disclosure. European Accounting Review 16(3):555-583.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Linthicum C, Reitenga AL, Sanchez JM (2010). Social responsibility and corporate reputation: the case of Arthur Andersen audit failure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 29(2):160-176.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lindblom CK (1994). The implications of organizational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure", paper presented at Critical Perspectives on Accounting Conference, New York.

|

|

|

|

|

Lightstone K, Driscoll C (2008). Disclosing elements of disclosure: a test of legitimacy theory and company ethics. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 25(1):7-21.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Liu S (2015). Corporate governance and forward-looking disclosure: Evidence from China. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 25:16-30.

Crossref

|

Lopes PT, Rodrigues LL (2007). Accounting for financial instruments: an analysis of the determinants of disclosure in the Portoguese stock exchange. The International Journal of Accounting 42(1):25-56.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Lundholm R, Winkle MV (2006). Motives for disclosure and non-disclosure: A framework and review of the evidence. Accounting and Business Research 36 (Special Issue):43-48.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Magness V (2006). Strategic posture, financial performance and environmental disclosure: an empirical test of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 19(4):540-563.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Morris RD (1987). Signalling, agency theory and accounting policy choice. Accounting and Business Research 18(69):47-56.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mulgan R (1997). The process of public accountability. Australian Journal of Public Administration 56(1):25-36.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Neu D, Warsame H, Pedwell K (1998). Managing public impressions: environmental disclosures in annual reports. Accounting, Organizations and Society 23(3):265-283.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

O'Donovan G (2002). Environmental disclosures in the annual report: extending the applicability and predictive power of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 15(3):344-371.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Patten DM (1992). Intra industry environmental disclosures in response to the Alaskan oil spill: a note on legitimacy theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society 17(6):595-612.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Petty R, Cuganesan S (2005). Voluntary disclosure of intellectual by Hong Kong companies: examining size, industry and growth effects over time. Australian Accounting Review 15(2):40-50.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pfeffer J, Salancik G (1978). The External Control of Organizations: A resource Dependence Perspective. Harper and Row, New York.

|

|

|

|

|

Robert HA (2010). Forward-looking information: What it is and why it matters. Journal of Government Financial Management 59(4):8-9.

|

|

|

|

|

Roberts R (1992). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure. Accounting, Organization and Society 17(6):595-612.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ross SA (1977). The determination of financial structure: the incentive signaling approach. Bell Journal of Economics 8(1):23-40.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ross SA (1979). The economics of information and the disclosure regulation debate. In. Edwards F (eds.), Issues in Financial Regulation. McGraw-Hill, New York. pp. 177-202.

|

|

|

|

|

Salama A, Sun N, Hussainey K, Habbas M (2010). Corporate environmental disclosure, corporate governance and earnings management. Managerial Auditing Journal 25(7):679-700.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schneider A, Samkin G (2008). Intellectual capital reporting by the New Zeland local government sector. Journal of Intellectual Capital 9(3):456-486.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shocker AD, Sethi SP (1974). An approach to incorporating social preferences in developing corporate action strategies. In. Sethi SP (eds.), The Unstable Ground: Corporate Social Policy in a Dynamic Society. Los Angeles, CA: Melville Publishing. pp. 67-80.

|

|

|

|

|

Shehata NF (2014). Theories and determinants of voluntary disclosure. Accounting and Finance Research 3(1):18-26.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Singh I, Van der Zahn J (2008). Determinants of intellectual capital disclosure in prospectuses of initial public offerings. Accounting and Business Research 38(5):409-431.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Singhvi SS, Desai HB (1971). An empirical analysis of the quality of corporate financial disclosure. Accounting Review 46(1):129-138.

|

|

|

|

|

Spence M (1973). Job market signalling. Quarterly Journal of Economics 87(3):355-374.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Spence AM, Zeckhauser RJ (1971). Insurance, information, and individual action. American Economic Review 61(2):380-387.

|

|

|

|

|

Subramaniam N (2006). Agency theory and accounting research: an overview of some conceptual and empirical issues. In. Hoque Z (eds.), Methodological Issues in Accounting Research: Theories and Methods. Spiramus Press, London. pp. 51-81.

|

|

|

|

|

Suddaby R, Greenwood R (2005). Rhetorical strategies of legitimacy. Administrative Science Quarterly 50(1):35-67.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sujan A, Abeysekera I (2007). Intellectual capital reporting practices of the top Australian firms. Australian Accounting Review 17(2):71-83.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tayles M, Pike R, Sofian S (2007). Intellectual capital, management accounting practices and corporate performance: perceptions of managers. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 2(4):522-548.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Thornburg S, Roberts RW (2008). Money, politics, and regulation of public accounting services: evidence from the Sarbanes-Oxley act of 2002. Accounting, Organizations and Society 33(2):229-248.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tilt CA (1994). The influence of external pressure groups on corporate social disclosure. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 7(4):47-72.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ulmann A (1985). Data in search of a theory: a critical examination of the relationships among social performance, social disclosure and economic performance of US firms. Academy of Management Review 10(3):540-557.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Uyar A, Kilic M (2012a). The influence of firm characteristics on disclosure of financial ratios in annual reports of Turkish firms listed in the Istanbul Stock Exchange. International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation 8(2):137-156.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Uyar A, Kilic M (2012b). Influence of corporate attributes on forward-looking information disclosure in publicly traded Turkish corporations. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 62:244-252.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vergauwen P, Alem F (2005). Annual reports IC disclosures in The Netherlands, France and Germany. Journal of Intellectual Capital 6(1):89-104.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Verrecchia R (1983). Discretionary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics 5(3):179-194.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wang M, Hussainey K (2013). Voluntary forward-looking statements driven by corporate governance and their value relevance. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 32(3):26-49.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wartick SL, Mahon, JF (1994). Toward a substantive definition of the corporate issue construct: a review and synthesis of the literature. Business and Society 33(3):293-311.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Watson A, Shrives P, Marston C (2002). Voluntary disclosure of accounting ratios in the UK. The British Accounting Review 34(4):289-313.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Watts R (1977). Corporate Financial Statements: A Product of the Market and Political Process. Australian Journal of Management 2(1):53-75.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Watts RL, Zimmerman JL (1978). Towards a positive theory of the determination of accounting standards. Accounting Review 35(1):112-134.

|

|

|

|

|

Watts RL, Zimmerman JL (1979). The demand for and supply of accounting theories: the market for excuses. The Accounting Review 54(2):273-305.

|

|

|

|

|

Watts RL, Zimmerman JL (1986). Positive Accounting Theory. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

|

|

|

|

|

Watts RL, Zimmerman JL (1990). Positive accounting theory: a ten year perspective. The Accounting Review 65(1):131-156.

|

|

|

|

|

Whiting RH, Miller JC (2008). Voluntary disclosure of intellectual capital in New Zealand annual reports and the 'hidden value'. Journal of Human Resource Costing and Accounting 12(1):26-50.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wilmshurst T, Frost G (2000). Corporate environmental reporting: a test of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 13(1):10-26.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Woodward DG, Edwards P, Birkin F (1996). Organisational legitimacy and stakeholder information provision. British Journal of Management 7(3):329-347.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Xiao JZ, Yang H, Chow CW (2004). The determinants and characteristics of voluntary internet-based disclosures by listed Chinese companies. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 23(3):191-225.

Crossref

|

|

|

|