Several studies have been conducted to establish the link between strategy, human resource management (HRM) practices and organisation performance, yet no study has explored the alignment between strategy, innovation, strategic HRM and their impacts on organisation competitiveness. Therefore, the present study sets out to align strategy, innovation, strategic human resource management (SHRM) and organisation competitiveness. The present study relies on in-depth review and synthesis of related literature in the field of strategy, innovation, strategic human resource management and organisation competitiveness to propose a model. The results show that aligning innovation and SHRM can enhance organisation competitiveness. The study found strategic HRM practices; learning, knowledge management, reward systems, recruitment, and performance management as critical to organisations’ innovativeness. The study offers both theoretical and practical implications for scholars as well as practitioners interested in the innovation. Despite all these claims, the study cautions against over-reliance on the findings, because of the qualitative nature of the study, hence future studies should consider empirically driven data (perhaps triangulations) to corroborate these results. The study offers a conceptual framework that could offer new insights into the relationship between strategy, innovation, SHRM and organisation competitiveness that has not been empirically tested before.

Innovation is not only considered critical for sustainable competitiveness of firms and industries, but also for regional and national development. Schumpeter (1942) first emphasised the vital role of innovation in generating creative destruction and subsequent economic growth in seminal work, "Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy”.

Until then, many corporate executives did not recognise innovation as the driver of organisations' and countries' competitive advantage (Agolla and Van Lill, 2013). However in spite of all these, there has been a

remarkable change of late as scholars, organisations and countries embrace innovation as the panacea to prosperity and growth in the twenty-first century and key to the 4th industrial revolution (Agolla and Van Lill, 2016).

Therefore, the current buzzword for scholars, practitioners and corporate organisations is “innovate” or “perish” (Agolla and Van Lill, 2013; Kafetzopoulos, Gotzamani, and Gkana, 2015). This underscores the importance and the role of innovation in both short and long run success of organisations and countries competitiveness. Snap shot overview of both developed and emerging economies have already proven that innovation does matter in terms of international competitiveness of both organisations and countries (Arunprasad, 2016).

For example, emerging countries namely Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa corporate organisations have joined the list of Fortune Global 500 of late, a fact that can perhaps be attributed to their innovativeness amongst other factors (Warner, 2011). Despite the rapid growth in the numbers of organisations in the list Fortune Global 500, the major challenges facing emerging markets is a lack of strategic alignment of human resource practices, innovation, strategy and competitiveness.

Innovation is a term that is used in different ways that in most cases create confusion as to what it really means (Kafetzopoulos et al., 2015). For example, a new technology introduced by an organisation, or a change in the production, process, or products/services can be referred to as innovation. However, the present study refutes such usage of the term “innovation” as change or introduction of new technologies may not necessarily have value (economic value) to the organisation.

Innovation can also be defined as the generation of new knowledge and ideas that facilitate new business outcomes. This is aimed at improving internal business processes and structures, and to create market-driven products and services; innovation encompasses both radical and incremental innovation (Du Plessis, 2007). On one hand, the OECD/Eurostat (2005) defines innovation as, “the implementation of a new or significantly improved product, process, marketing method, or organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations” (OECD, 2005).

Therefore, the present study conceptualises the definition of innovation as, introduction or implementation of new ideas, or generation of creative ideas to improve processes, products, and services that result in economic value to the organisations (Amabile, 1996). This simply means ideas must be generated by employees, experimented with by the organisation’s members, and implemented in order for organisations to realise its economic value. Notwithstanding the controversy in the definition of innovation, several studies have confirmed competitiveness, and standard of living (Agolla and Van Lill, 2016; Kafetzopoulos et al., 2015).

Whereas extant literature reveals the importance of innovation in driving organisations’ business bottom line, still then, there is dearth in literature establishing a link between innovation, strategy, and SHRM and organisation competitiveness. Several scholars have studied innovation in the context of individual, groups and organisation levels. However, there is a lack of studies in examining the interrelations of several SHRM practices, innovation, and organisation strategy in their contribution to organisational competitiveness.

Given the paucity of literature in the area, the study aims to fill this gap through establishing a link between strategy, innovation, strategic human resource management and organisation’s competitiveness. Therefore, the primary question of the present study is:

To what extent are there interrelationships between organisation strategy, SHRM, innovation and organisation competitiveness?

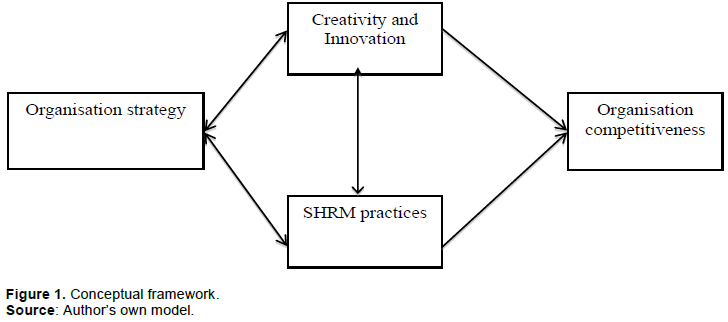

First, the paper theoretically explores innovation concept, organisation strategy, strategic human resource management practices (recruitment, organisation learning, knowledge management, reward systems, and performance management) and organisation competitiveness through in-depth analysis and synthesis of literature to propose a theoretical framework. Literature mining was done through the use of the keywords (innovation, strategic human resource, organisation strategy and competitiveness, creativity) on Emeralds insights, Springer, and Elsevier databases. Following an in-depth analysis and synthesis of literature, a conceptual framework, which will serve as a guide for the discussion on the alignment of strategy, strategic human resource management (SHRM), innovation and organisation competitiveness was developed (Figure 1).

Conceptual and theoretical framework

In order to discuss the relationship between strategy, innovation, strategic human resource management and organisation competitiveness, this study presents a conceptual framework as indicated in Figure 1. It theorizes the relationships between organisation strategy, innovation, strategic human resource management practices and organisation competitiveness. The arrows indicate the interactions of the variables. These variables have been theoretically discussed in the subsequent paragraphs showing the link and contributions to organisation competitiveness.

Organisation strategy

Organisational strategy forms one of the biggest drivers of successful innovation because strategy provides integration and consistency, and enables powerful and easy communication of the strategy to organisational members (Azis and Osada, 2010; Cankar and Petkovšek, 2013; Dumay et al., 2013; Pekkarinen et al., 2011). For example, scholars (Cankar and Petkovšek, 2013; Dumay et al., 2013) looking specifically at factors that stimulate innovation and creativity suggest five factors: strategy, structure, support mechanisms, behaviour and communication.

Oke (2008) states that innovation strategy provides a clear direction and focuses the effort of the entire organisation on a common innovation goal. Therefore, management needs to develop the strategy and communicate the role of innovation within an organisation, decide how to use technology and drive performance improvements through the use of appropriate performance indicators (Cankar and Petkovšek, 2013; Pekkarinen et al., 2011).

Similarly in another study, Dobni et al. (2015) state that the first step in formulating an innovation strategy is to define what innovation means to the firm or the areas of focus in terms of innovation (Figure 1). By understanding the drivers of innovation needs, a firm can develop its focus areas for innovation. Innovation strategy needs to specify how the importance of innovation will be communicated to employees to achieve their buy-in and must explicitly reflect the importance that management places on innovation as shown in Figure 1. This is only possible when the management of the organisation crafts a strategy that is well integrated and aligned with the organisational critical resources (strategic human resource management practices) for the successful innovation (Serrano-Bedia et al., 2012 and Jiménez-Jiménez and Sanz-Valle, 2005). However, research indicates that strategy poses one of the greatest barriers to successful innovation in the organisation, particularly if it is communicated to organisational members in a cryptic or incomplete manner, hoping that employees will understand how it all fits together (Agolla and Van Lill, 2013).

Dobni et al. (2015) state that an organisation must ensure employees understand the organisation’s vision and mission (which support creativity and innovation) and the gap between the current situation and the vision and mission in order to act creatively and innovatively (Figure 1). Murray et al. (2010) further point out that serious innovation is linked to organisational strategy. It is through this that the organisations can achieve effective outcomes. Murray et al. (2010) argue that strategic considerations should drive a significant share of organisation innovation funding, specifically first identifying priority issues; cost, resources; organisation concerns; fields where there are gaps between current performance and expectations and secondly, identifying in each field to what extent strategic goals can be met by adopting already proven innovations or developing new ones (Cankar and Petkovšek, 2013).

It is the strategy that drives the core purpose of organisation existence. Organisational strategy plays an important role in driving an organisation to innovate through careful alignment of core human resource functions as shown in Figure 1. Organisations contemplating an innovation strategy, needs to have creative employees who are flexible and tolerant of uncertainty and ambiguity; people who are able to take risks and assume responsibilities, very skillful, able to work in a cooperative and interdependent way and with a long-term orientation (Jime´nez-Jime´nez and Sanz-Valle, 2005).

However, strategic success also depends on strategic leadership with clear communication of the organisation’s vision, successful alignment of the strategy, and the ability to change the approach, through integration of SHRM, and innovation capabilities to enhance performance.

Availability of material resources

Organisational success does not solely depend on how well rewarded its employees are, but how the organisation complements these rewards with material resources to enable employees to experiment and research for new products, services, or processes with the aim to create unique values for the organisation. The evidence (Agolla and Van Lill, 2013; Carstensen and Bason, 2012) suggests that innovation requires substantial investment in resources in order to carry out research before the actual innovative outcomes. These material resources range from financial, physical resources, infrastructure, and raw materials as inputs to the service process (Agolla and Van Lill, 2013; Conteh, 2012; Liu, 2011).

Innovation requires trying new ideas that have never been tried or tested before and carries with them huge risks in terms of the resources invested (Albury, 2011; Mulgan and Albury, 2003). It is these resources that the organisation needs to provide for employees to carry out innovation activities (Mele et al., 2010). The failure of such risk-taking may mean substantial financial loss or closure of the entire project, but that should not limit the support from the organisation since there is no innovation without any risk taking or losses (Natário et al., 2012). There should be a balance between risk taking and risk management in order to bring risks within manageable levels. This is what ought to be done in order to promote innovation and eliminate the fear of risk-taking in the Organisation.

Employees require materials for the purposes of experimenting, research or trying new methods of services that have not been tried or tested before; therefore they need assurance that if such projects fail, then they will not be punished. Instead, mistakes or failure should offer a learning opportunity for further development (Murray et al., 2010). An example of how to deal with such mistakes or heavy losses, both in terms of material and human resources can be drawn from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The National Aeronautical and Space Administration is a United States agency that has received constant funding from the organisation of the United States in their quest to try out new things despite encountering heavy losses in terms of material and human resources. This is a typical example of how organisation support is required in the face of adversity.

Developing countries also can borrow from experiences such as those of the USA, UK, Sweden, Finland and many others, and provide resources to an organisation, train employees in risk management and experiment with the limited resources at their disposal in order to promote innovation (Adrianpoulos and Dawson, 2010). Studies (Agolla and Van Lill, 2013; Adrianpoulos and Dawson, 2010) have indicated that material resources are always inadequate, and therefore there is a need to create innovation funds that would be dedicated to innovative ventures separate from other resources that the organisation might have at its disposal.

Creativity and innovation

Most scholars conceptualise creativity as the development of ideas about products, services, practices, or procedures that are novel and potentially valuable to a department or organisation (Amabile, 1996; Shalley et al., 2004). Creativity is the original ideas that lead to innovation and must be distinguished from the application of new technology because the latter can be purchased, while the former may not. This is because ideas can only come from a living human being working in an environment that encourages such creative thinking. This calls for strategic link between corporate strategy and innovation imperatives that allow employees to be free in their expressions of ideas (Figure 1).

Studies have shown for example that for employees to generate and experiment with ideas, organisations top management/leadership must put the right mechanisms in place. Mechanisms require the alignment of creativity, strategic human resource management (SHRM), strategy and organisation competitiveness (Figure 1). Notably, some of the work environment characteristics that have been found to foster creative ideas are freedom, independence, autonomy good role models and resources (including time), encourage originality, freedom from criticism and “norms in which innovation is prized and failure not fatal” (Agolla, 2015; Antikainen et al., 2010 and Sarac et al., 2014).

Creativity is a choice made by an individual to engage in the production of novel ideas. Therefore for this choice to materialize, organisation needs to provide enabling work environment that motivate individual employee to generate creative ideas (Ahmetoglu et al., 2016). The level of creative engagement may depend on the person and the situation. Moreover we must take note that, an individual may choose minimal engagement although the person has great potential depending on the circumstances and situation prevailing at that time (Sarac et al., 2014).

Once creative individuals have been recruited or identified within an organisation then processes need to be implemented to help them develop. Corporate culture can be a stumbling block and this must be addressed if innovators are to be nurtured. Having a degree of autonomy and flexibility is important to many creative thinkers. Appropriate mentoring, particularly the use of multiple mentors, and the development of supportive peer networks are tested strategies for developing the potential of creative employees.

Merrill (2008) suggests that several different types of innovative individuals are required to make any innovation a success. These include the ‘‘creators’’, the people usually considered the key to an innovative approach. However ‘‘connectors’’, ‘‘developers’’ and ‘‘doers’’ are all important in any peer network as they help to move innovation forward at different stages of a project.

Another key to supporting innovation is finding the right niche for innovators in the organisation structure. For organisations like Google with a very flat management structure, this may not be a problem (Brockett, 2008). However, most firms are less egalitarian and therefore may struggle to reward innovation while at the same time avoiding promoting innovators into roles that do not enable them to utilise their skills to the greatest effect (Brockett, 2008).

Reuters has developed a solution, which is in itself innovative. They have created ‘‘innovation hubs’’ at the heart of the corporate structure where creative thinkers can be given the autonomy to develop ideas without being burdened with too many management responsibilities. This is further demonstrated through a link as shown in Figure 1. In other study, Merrill (2008) proposes this model of innovation, which can be adopted by organisations wishing to foster creative thinking, or by individuals wishing to improve their own powers of innovation. The six stages of this model are:

(1) Exploring

(2) Interacting

(3) Observing and note taking

(4) Collaborating

(5) Experimentation, and

(6) Embracing failure.

The first stage is about giving employees that all-important thinking time which is often not valued in organisations that embrace rigid time management models. ‘‘Doing’’ is all too often seen as the only valid activity in the workplace and an employee caught daydreaming, doodling or engaged in any other mind-freeing activity encouraging right brain thinking might be reprimanded or even disciplined for failing to conform to the accepted workload model. Organisations wishing to foster innovation must begin to change the corporate culture that values doing while neglecting the importance of thinking. Therefore, incorporating SHRM practices with strategy and innovation imperatives will help employees to feel free to collaborate and interact as shown in Figure 1.

Interacting and collaborating are both important stages of the model as creativity feeds on shared ideas and experiences. Kaye Foster-Cheek of Johnson and Johnson describes innovators as having a unique psychological mix, as they can work autonomously but also function well in large interdisciplinary teams. Merrill (2008) suggests that getting out and meeting different people and having new experiences helps employees to see the world in a new way. Many people find that debating or brainstorming ideas with a colleague can stimulate the creative thinking process. This becomes increasingly important as ideas are developed through various planning stages. A team approach can translate a great idea into something that can actually be produced and marketed.

“To question someone else’s reasoning is not a sign of mistrust but available opportunity for learning” (Argyris, 1991)

In fact managers should take pride on those employees who challenge and question their decisions and reasoning styles, and if possible celebrate them for such criticisms. Criticisms from your subordinates, peers or fellow colleagues only meant to show that, we are different regarding our perceptual cognitive. Observing and note-taking may not be an immediately obvious stage of an innovation cycle but Merrill explains that carrying a notepad wherever you go, helps to hone one’s powers of observations and can help to capture creative ideas wherever and whenever they occur.

Embracing failure may also seem counter-intuitive, especially as today's businesses coaches often stress the importance of developing a ‘‘success'' mindset. However, failure contributes to success by demonstrating what does not work. Much of the technology we take for granted today only exists because inventors did not give up when their first attempts ended in failure. Apparently, Thomas Edison tested 6,000 different materials before he found one that could be used for the filament inside the light bulb. Edison is a good model of an innovator who was able to analyse his failures and then carry on experimenting until he achieved success.

In Figure 1, innovation refers to the process in which an enterprise supports new ideas, provides human resources and material resources with new ideas and, ultimately, transforms the new ideas into new products, new services or new management means (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996). Innovation is an important aspect that organisations have to take into consideration when developing their business strategies to build and sustain competitive advantage (Plessis, 2007).

Innovation has been synonymous with successful implementation of creative ideas or improved products, process or service or introducing new technology that has economic value. Studies have shown that innovation does not just come out of nowhere, but rather generated by organisations members working individually or in groups. For innovation to take place, organisation members generate creative ideas that are unique. Such ideas are tested and tried by organisation’s members before implemented and their viability put to test (Inkinen et al., 2015).

Therefore, creativity is a precursor for innovation to take place. To achieve the desired outcomes such as creativity and innovation, substantial attention has to be given to how employees as enablers of creative and innovative outputs leadership, practices and policies that encourage or restrain creativity and innovation in the organisation (Khalili, 2016).

What really take place at innovation phase in organisation? Literature indicates that at innovation phase/stage in the organisation, ideas generated at creativity level, are tried, experimented with and implemented to realise its economic value to the organisation. This implementation includes commercialisation of innovative outputs. At this phase, we need to recognise that, there are various types of innovation, and depending on what industry an organisation is in. Innovation (the successful exploration and commercialisation of new ideas) has to underpin ever-higher value-adding products, services and processes (Li-Hua, 2007). Furthermore, Brem et al. (2016) add that innovations can be distinguished as product, process, or service innovations.

Recruitment

It is well known that recruitment represents one of the core corporate talents acquisitions that need to be efficiently and effectively executed for organisations to be competitive locally, regionally and internationally. This is because recruitment marks the entry into marriage between the organisations and employees. Therefore, efficient and effective recruitment process will naturally trigger bottom line business.

Most studies (Darrag et al., 2010; Warmerdam et al., 2015) have examined efficient and effective recruitment process as one that seeks to acquire employees who are experienced, skilled, interpersonal skills, communication skills and knowledge while ignoring critical areas such creative, innovative, and transformative. Organisations that have made a stride in the areas have long adopted and changed how recruitment are carried out, and know exactly what efficient and effectively recruitment process entails (Warmerdam et al., 2015).

The 21st Century organisations have long moved away from seeking for job candidates who only possess traditional known attributes such as knowledge, skills, experience, and abilities, but rather go after those job candidates who are capable of challenging the status quo. Modern organisations have made it pre-employment conditions for job candidates to have creative, innovative and transformative abilities beside other traditional requirements. Scholars unanimously agreed that having the right employee is the foremost driver of organisational effectiveness for the future (Acarlar and Bilgiç, 2012; Chapman et al., 2005).

For instance, in their study of recruitment of Generation Y (Gen Y) using Ajzen (1980) Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and Warmerdam et al. (2015) to understand graduate intentions to join an organisations found that Gen Y are the most technologically literate generation and conduct internet-based job searches. Therefore, organisations with a careers or employment section on their website (with a link to making a job application) subsequently make it easier for Gen Y to apply, and the findings of the current research support the assertion that the organisation will receive more Gen Y applicants. This suggestion must be executed while bearing in mind the other findings of the current research. Gen Y also assesses their suitability for the position (capability of joining). This implies that as much as organisations may have job openings, and job applicants may also be looking for an opening, both parties must bear in mind that, each must appeal to each other on equal measure.

Cohn et al. (2008) concur that finding the right people is the key to developing a culture of innovation in the workplace. They suggest that innovators share some key personality traits that can be identified and fostered. Innovators have a strong analytical intelligence combined with a sense of insecurity. Innovators can identify problems and find solutions but never depend on past solutions for current problems. Innovators approach every situation with fresh eyes. Innovators can sometimes appear somewhat gauche; they may not fit an accepted corporate profile. However, in reality, they have a keen social awareness enabling them to ‘‘read’’ developing situations with a keen accuracy. Successful innovators also have the charm required to persuade others to adopt their ideas.

As everyone seems to agree that the right people are the keys to successful innovation, is it possible to identify innovators at the recruitment stage? Even Google does not always find this easy, as they are notorious for their multiple stage interviews (Brockett, 2008). However, the current head of HR at Google, Liane Hornsey, reports that the average number of interviews has been halved to ‘‘only'' four or five per candidate! While such intensive interviewing may have significant resource implications, the process which Google uses to interview prospective employees could be adopted elsewhere (Brockett, 2008).

Known as ‘‘360-degree interviewing'' this process involves peers and subordinates as well as managers and all members of the panel have the right to veto an appointment. Some firms, such as Reuters, depend on internal recruitment to identify potential innovators. Using a series of interviews, the organisation looks for the candidate's ability to develop and defend an idea. The final hurdle is to demonstrate an analytical understanding of failure. According to Reuters, a candidate who does not have the self-awareness to confidently discuss his or her areas of weakness will never make a successful innovator. McDonald’s uses existing structures such as systematic performance reviews to identify potential talent (Brockett, 2008).

“To innovate successfully, you must hire, work with,

and promote people who are unlike you” (Leonard and Straus, 1998).

Innovative organisations hire, work with, and promote people who make them uncomfortable, this is because managers need to understand their own preferences so that they can complement their weaknesses and exploit their strengths (Leonard and Straus, 1998). Organisations should encourage recruitment process that allow for workforce mix irrespective of ethnic orientation, religious belief, age, gender and social background. This is because no single human race can lay claim creative minds alone in exclusion of others. Innovation can come from anywhere, anytime, and from a creative thinking living human beings. Therefore, organisation’s innovation, HRM practices, should be linked to organisation strategy to create competitive advantage (Figure 1).

Organisation learning

Apart from the conventional attracting, training, retaining and motivating the employees, the strategic human resource management (SHRM) practices (see Figure 1) should enhance and provide a good learning culture where free transfer of knowledge takes place in the work environment (Arunprasad, 2016).

Organisation learning refers to sets of practices useful to organisations in developing the ability to learn and to know how they learn (Mele et al., 2010). Organisation learning also implies the freedom to take risks, to practice and experiment, and to make mistakes (Moustaghifir and Schuima, 2013). This is because learning is fundamental to finding innovation potential. Whereas learning is seen as the fundamental to finding innovation potential, this has not been the case with the organisation. However, it should be noted that most organisations are not accustomed to continuous learning. This is because continuous learning is associated with disruption of operations, hence organisation employees are always pre-occupied with policy implementation and how to maintain procedures that have worked so well in the past instead of trying new things altogether (Murray et al., 2010).

Therefore, training is more of maintaining the status quo as opposed to learning new things that require improvements in outcomes (Engida and Bardill, 2013; Lankeu and Maket, 2012). The organisation should invest in the areas of strategic thinking, creativity and innovation that are critical to the organisation’s success as they are fundamental functional skills (Fryer et al., 2013). It is this investment in the area of strategic thinking that will pay off when members of the organisation are able to recognise causal relationships between their assumptions or actions and the behaviour of the customers (organisation). Organisation learning is the source of creativity and innovation (Fryer et al., 2013; Belkahla and Triki, 2011).

“Learning organisations cultivate the art of open, attentive listening. Managers must be open to criticism”. Garvin, 1993.

In learning organisations, individual and collective learning processes can be distinguished; the quality of a learning organisation is apparent when individuals have an impact on one another (Moustaghfir and Schiuma, 2013). In fact, it is these mutual processes of interactions that lead to behavioural changes, (mostly in the form of scripts or collective routines) leading to innovation learning which is the power of the learning organisation (Lee et al., 2012). Similar studies (Rivers, 2001; Isaacson and Fujita, 2006) posit that metacognition, that empowers learners with a self-regulated learning mechanism, is the best learning strategy. The argument here is that the focus of a learning organisation is to improve the potential of the individual employees in terms of metacognitive learning. Albury (2011) adds that creative ideas can arise from anywhere, at any time, but if managers seek to harness creative individuals to foster innovation, they should not only provide organisation with a structure in which innovative ideas are encouraged to appear, but also to ensure that an appropriate reward system is in place so that they continue to emerge.

Knowledge management

In the 21st Century, new organisations are emerging where knowledge is the primary production resource as opposed to capital and labour (KumpikaitÄ—, 2007). It now believed that efficient utilisation of existing knowledge could create wealth for organisations. Knowledge management (KM) refers to the process of enhancing organisation performance by designing and implementing tools, processes, systems, structures and culture to improve the creation, sharing, and use of knowledge (DeLong and Fashey, 2000; Inkinen et al., 2015; Rosset, 1999).

Knowledge is becoming progressively more useful because management is taking into account the value of creativity, which enables the transformation of one form of knowledge to the next. The perception of the existing relationships among several systems elements leads to new interpretations and this means another knowledge level where a new perceived value is generated (Inkinen et al., 2015). This relationship indicates that the innovation highway depends on the knowledge evolution (Carneiro, 2000; Inkinen et al., 2015). This relationship has well been captured in the proposed conceptual framework of the present study (Figure 1).

Extant literature (Plessis, 2007; Obeidat et al., 2016) showed that knowledge creation or acquisition, knowledge sharing and knowledge leverage or utilisation build employees' skills are relevant to the process of innovation. KM also that facilitating collaboration between employees and sectors will enhance the knowledge sharing and utilisation, which will, in turn, increase innovation (Figure 1).

Therefore based on the previous studies knowledge, sharing plays an important role in innovation. Studies have shown that encouraging knowledge sharing between employees and incorporating KM into strategies will lead to gaining competitive advantage, customer focus and innovation (Obeidat et al., 2016; Mas-Machuca and Costa, 2012). Similarly, Huang and Li (2009) argue that organisations could trigger off the sharing, application and deployment of knowledge to facilitate innovation, because KM has a positive effect and contribution to transform tacit knowledge into innovative products, services and processes, which improve innovative performance as shown in Figure 1.

Some studies showed that there is a relationship between organisational innovation and knowledge transfer as well as reverse knowledge transfer, but its effect depends heavily on learning orientations (Obeidat et al., 2016; Jimenéz-Jimenéz et al., 2014). In gist, two key elements are important in the definition. From the review of the literature, the present study found evidence that knowledge is the core component of innovation – not technology or finances.

“To be remain competitive, may be even to survive businesses will have to convert themselves into organisations of knowledgeable specialists” (Drucker, 1988).

In summary, Arunprasad (2016) opines that, strategic HRM practices are deployed in organisations to ensure a competitive advantage by focusing extensively towards the human resources and build the knowledge base for a sustained growth. From the strategic HRM perspective, a set of integrative HR practices that support organisation’s strategy produces a sustainable competitive advantage (Figure 1).

Performance management

Performance appraisal/management forms an important aspect of employees’ career aspiration as well organisation’s overall objectives. The aspiration component of employees is a desire for advancement, influence, financial rewards, work-life balance, and overall job satisfaction that effective performance must help employees achieve (Gateru et al., 2013; Gatherer and Craig, 2012). Innovative organisations go for performance management systems that manage the core values they cherish. For example, if the organisation values creativity, problem-solving and innovative behaviour as some of the critical attributes beside the traditional performance functional areas and competencies, such organisation would place more emphasis on those core values. That means employees performance management and appraisals would be inclined towards those attributes. The people who work in the organisation determine its value. To grow and prosper, organisations in the first place, and above all need to be creative brains. Creativity is the mainstay of a modern organisation. Hence, the need to have effective performance management systems that embrace all key aspects of creativity, innovation and reward such employees who have demonstrated such attributes (Uzkurt et al., 2013). For example, Buller and McEvoy (2012) state that organisational and individual factors should be aligned because, among other factors, the performance of organisation depends on the individual and collective behaviour of the employees. Furthermore, this alignment facilitates the creation of human and social capital to achieve superior performance (Bendoly et al., 2010).

Reward systems

The organisation reward systems play a critical role in attracting key employees and to enable them to retain valued staff (Abury, 2011; Lankeu and Maket, 2012). Research indicates that appropriate reward systems will not only attract and retain the qualified staff but would go a long way in motivating them to perform to their best ability (Gatere et al., 2013; Lankeu and Maket, 2012:269). Innovation ideas bring value to the organisation, therefore organisation managers need to align the reward systems with the individual and group performance so that those employees are rewarded adequately for their personal contribution towards creativity and innovation. Engida and Bardill (2013), Gatere et al. (2013) and Lankeu and Maket (2012) identified rewards as drivers to creativity and innovation, and suggest that for the organisation to innovate their reward systems should be competitive not only to attract and retain their most valued employees, but also encourage employees to be creative and innovative. Besides the rewards systems in place, the organisation must strive for the availability of other material resources that are also very crucial and critical for fostering innovation.

Organisation competitiveness

Innovation is widely recognized to be critical for sustaining the competitive advantage of firms and industries, and at the regional and national levels (Sheehan et al., 2014). Studies have shown organisations that opt for innovation have a competitive advantage if they come up with new ideas and create services and products that are, at least partly, unique (Brem et al., 2016; Molleman and Timmerman, 2003; Sheehan et al., 2014). Innovative organisations are known to have a competitive advantage through the creation of services and products that are not easily imitable by other competitors (see Figure 1).

Therefore, the organisations’ survival in nature is all about having the opportunity to compete and then acquiring the tools for the conquest of that environment (Sheehan et al., 2014). The competitive advantage of an organisation originates from the possession of special resources, for example, innovation capability, and cannot be imitated and substituted (Guan et al., 2006). These resources ensure an organisation maintain a superior position in strategy, technology, and management (Liu and Jiang, 2016). To remain competitive and sustainable in changing and highly competitive business environment, organisations have to invest in creativity and innovation. Creativity and innovation are considered to be the most important capacity for organisations that wish to establish a competitive advantage (Gisbert-LoÌpez et al., 2014).

The competitiveness of an organisation is dependent upon the various factors: the degree to which organisations are capable of penetrating the markets and sustain it; uniqueness of services, products and how such outputs are differentiated from their competitors; market shares the organisation is able to control; and the performance based on revenue generation (Figure 1). First, we need to recognise the role innovation plays in helping organisations gain a competitive edge through the implementation of unique and creative services, cutting-edge technologies and products that are not easily imitable by the other competitors.