ABSTRACT

Over the last few years, laws concerning the waste sector have changed considerably. The European and national laws apply strict rules to companies in order to protect the environment and quality of life. The issue of sustainability is receiving increasing attention, and many organizations have implemented environmental and social management systems in order to manage and control sustainability-related issues. This paper examines whether sustainability-oriented goals have been identified and managed through appropriate strategic planning tools in several Italian state-owned waste companies. This question is examined using a business model highlighting the cause-and-effect relations among key success variables, according to social and environmental patterns. The empirical analysis uses multiple case studies conducted through interviews with managers holding key positions within organizations and an investigation of internal documents. The results show a high diffusion of social and environmental goals although their management through advanced managerial systems is still limited. This work has important theoretical and practical implications because it extends the existing literature on sustainability and strategic planning tools in public utility companies and provides a guide for further reflections on this topic.

Key words: Waste sector, public utility, sustainability, strategic planning tool, strategy map

The waste sector is being impacted by the increasing prescriptive efforts to safeguard the environment and human wellbeing. Increasing waste production is creating environmental and social problems, for which waste companies are partially responsible. Companies can keep these problems under control through the creation of partnerships with local communities and by engaging fully in the pursuit of social and environmental goals. The Italian waste sector is complex, especially in terms of regulatory and legislative processes. Unfortunately, the transformation process has not been smooth, and Italian waste policy has been characterized by a high degree of fragmentation among laws and regulations. The proliferation of laws resulted from the need to cope with various European Union Directives. European and Italian laws (Directive 2000/60/EC and Italian Legislative Decree 152/2006) apply strict rules to companies in order to protect the environment and countries’ quality of life. National and regional laws define their objectives in terms of the collection, separation, and recycling of wastes. Italy’s waste production is increasing (by +0.3% since 2015). Data on waste production per head indicate that the highest values have been reached in central Italy, followed by the northern and southern regions (ISPRA Report, 2015). In 2014, the highest recycling rates were recorded in the northern regions of Italy (56.7%), followed by the center (40.8%), and the south (31.3%). Three alternative ways to delegate waste services delivery are available: in-house contracts, public tenders aimed at identifying a private service provider, or public–private partnerships (PPPs). The pursuit of social purposes and the promotion of the economic and social development of local communities are distinctive aspects of companies working in public utility sectors, such as the waste sector. These companies should thus define their strategies and goals on the basis of the needs of their stakeholders and the specific needs of their area of operations without neglecting the political and legal constraints affecting current and future planning. Analyses of the external environment in which companies operate and the relevant intra-organizational factors seem propaedeutic to a definition of their strategies and expected results. In this context, it is useful to discuss sustainability and its three main components: economic (e.g., profitability, cost saving), social (e.g., stakeholders, public welfare) and environmental (e.g., protection of the environment and area of operations). Company behavior and performance can strongly impact the environment and human wellbeing. This study focuses on several Italian state-owned waste sector companies that offer one or more of the following services: the collection of undifferentiated and recyclable wastes, transportation services to disposal centers, the management of disposal centers, and urban hygiene services (e.g., road and park cleaning).

The literature (Hood, 1995; Boston et al., 1996; Northcott and Taulapapa, 2012) shows that, in the last decades, public sector organizations around the world have faced increasing pressure to demonstrate effective performance management. Thus, performance management practices previously confined to the private sector have begun to be used by companies that offer public services as a means of improving their performance and accountability (Hood, 1995; Jackson and Lapsley, 2003; Perera et al., 2003; Lapsley and Wright, 2004). However, few studies have focused on advanced management control systems in the public sector (Northcott and Taulapapa, 2012). This study fills this gap by analyzing how sustainability issues are managed through appropriate strategic planning tools in several Italian public utilities operating via in-house contracts (state-owned) in the waste sector.

Results show that, according with the main literature on this topic, in the sample of public utilities analysed the sustainability strategic planning systems are not wide-spread. Consequently, this work proposes a business model focused on sustainability-related issues, in order to provide companies with the logical tools to support internal and external decision-making and communication processes. The proposed sustainable business model has been successfully implemented by some companies: some of those declared benefits such as a better communication with key stakeholders or a significant support in internal decision-making process.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The section below presents a literature review. The study’s empirical research method is then described. Next, the findings are outlined and discussed. Finally, the paper ends with concluding remarks.

Sustainability management

Sustainability management is not a new topic; however, it continues to have international significance for both the private sector and the public utility sector (Boyce, 2000; Frost and Seamer, 2002; Line et al., 2002; Vagnoni, 2001). European and national laws, which apply strict rules to public utility companies such as waste sector firms, have helped increase the attention being paid to sustainability, particularly concerning the promotion of efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability (Maruccio and Steccolini, 2005). It becomes increasingly clear that, to survive and thrive, organizations must make decisions that serve the interests of the environment and society (Adams and Frost, 2008). In recent years, several companies have recognized the potential of sustainability-oriented behaviors and have begun to use internal and external reports to manage, control, and communicate sustainability-related issues (Bieker et al., 2002), but what does “sustainability” mean?

The term “sustainability” is closely tied to “sustainable development,” although it is difficult to define clearly. An early definition, included in the Brundtland Report of 1987, described “sustainable development” as “the ability to meet the needs of the present without compromising the possibility of future generations to meet their own needs.” Usually, “sustainable development” highlights the interdependence of the economic, social, and environmental spheres (Elkington, 1997). Such an approach to sustainability management aims at the simultaneous achievement of ecological, social, and economic goals (Figgie et al., 2001; Schaltegger and Burrit, 2000; O’ Connor, 2006). O’Connor (2006) introduces a fourth sphere, the system of regulation that arbitrates among the claims made by the actors in the social, economic, and environmental spheres. The analysis of sustainability also focuses on the interactions and interdependencies among these spheres and on the characterization of the performance and quality in each one. Nidumolo et al. (2009) has also defined sustainability as a key driver for innovation, pointing out that the search for sustainability is transforming the competitive arena, leading to a rethinking of the characteristics of products, technologies, processes, and business models.

It is thus becoming increasingly important for both public utility sector and private sector firms to formulate strategies that identify the sustainability goals that need to be managed and communicated at different levels of the organization.

Translation of sustainability strategy into operational terms

Kaplan and Norton (2000) identify several strategic themes. One of them, “be a good corporate citizen,” can be considered sustainability-oriented because it is focused on managing relationships with external stakeholders, especially in areas subject to regulation (e.g., utilities, healthcare, telecommunications), safety concerns, and environmental risk management. Bieker et al. (2002) identify different sustainability-oriented competitive strategies:

i) The “safe” strategy aims to manage, prevent, or control the harmful effects caused by behavior inconsistent with sustainability;

ii) The “credible” strategy is a common strategy in sectors where reputation and credibility provide competitive advantage. Through this strategy, companies seek to prevent conflicts with stakeholders and create a positive image;

iii) The “efficient” strategy combines efficiency and sustainability in process management;

iv) The “innovative” strategy aims to differentiate products and services from those offered by competitors. In this case, the company’s approach to sustainability can be considered a source of competitive advantage;

v) The “transformative” strategy consists in being an active part of the institutional changes in the market, such as pushing towards social and/or environmental reporting.

After defining a strategy, it is necessary to translate it into operational terms. Indeed, the ability to execute a strategy is as important as the strategy itself (Kaplan and Norton, 2000). The theme of sustainability can be included along with strategic intentions and the related critical success factors in the creation of an organizational sustainability-oriented culture (Epstein and Buhovac, 2014; Epstein and Roy, 2001; Schaltegger et al., 2012). The research has also emphasized the importance of identifying the sustainability indicators within business performance models (Epstein and Buhovac, 2014; Schaltegger and Wagner, 2006; Figge et al., 2002; Dias-Sardinha and Reijnders, 2001). The strategy map and balanced scorecard, theorized by Kaplan and Norton (1992, 1996, 2000, 2004), play a key role in translating strategy into action because they force managers to identify the key success factors and their cause-and-effect relations to a greater extent than other strategic planning tools do. Key success factors are specified within four perspectives (learning and growth, internal processes, customers, and financial) and are then measured with a balanced set of financial and non-financial indicators.

These tools have been criticized for failing to consider several variables, such as the effects on the environment and the community in which the organization is operating (Smith, 2005). However, Kaplan and Norton (1996) argue that this framework cannot be considered a “straitjacket” but, on the contrary, can be adapted to environmental and social issues. The flexibility of the strategy map and balanced scorecard allows managers to choose an approach that works best with the company’s strategic goals, corporate culture, and sustainability (Butler et al., 2011). Some authors (Bieker et al., 2001, 2002; Dias-Sardinha et al., 2002, 2007; Figge et al., 2002; Fülöp et al., 2016; Hódi Hernádi, 2012) suggest a Sustainability Balanced Scorecard, based on the theorization of Kaplan and Norton, but with a focus on sustainability-oriented competitive strategy. It provides a broader scope by showing the causal links among the key economic, social, and ecological factors. Sustainability can be added to the original four perspectives of the strategy map as a different perspective, or the social and environmental aspects can be combined (Figge et al., 2002). Figge and Hahn (2001) proposed the inclusion of an additional perspective, the non-market perspective, especially for companies significantly influenced by social and environmental factors. Bieker et al. (2002) also suggest an additional perspective—social or environmental—to address the strategic orientation of sustainable development. Brusa (2007) states that the economic and financial perspectives reflect the constraints on public utilities rather than their main goals. Epstein and Wisner (2001) suggests a list of social and environmental indicators that should be included within the four “classical perspectives.”

Whichever framework is chosen, this tool has limitations, as social impacts are not easy to measure or quantify (Huang et al., 2014). Several studies (Dias-Sadinha and Reijnders, 2005; Moller and Schalteggar, 2005; Sidiropoulos et al., 2004) on the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard have focused on sustainability indicators such as those linked to eco-efficiency, which are easily quantified. However, as suggested by Moller and Schalteggar (2005), a comprehensive framework should connect all the pillars of sustainability. If a company is able to properly manage sustainability issues, the information generated from the Balanced Scorecard and other strategic planning tools should not be used solely for internal purposes. Companies can become more transparent and inform external stakeholders about their sustainability performance (Butler et al., 2011). One way to do this is through external reports such as Integrated Reporting and Sustainability Reporting, based on guidance from the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), respectively. These documents externally disclose the most critical impacts on the environment, society, and economy and can influence the process of organizational legitimacy assessment (Gray et al., 2009; Greiling and Grüb, 2014). Despite their relevance, these reports represent only a final output, which should be preceded by the identification of the drivers and processes leading to the development of an organization’s sustainability culture and practices (Huang et al., 2014). The strategic planning tools provide the foundation regardless of which structure is chosen. They can support the implementation of a sustainability-oriented strategy and help drive the organizational structure as it works toward sustainability goals.

Although the relevance of strategic planning and management control systems is widely recognized, many managers of public utilities seem to ignore them or choose not to apply them (Martinez et al., 2015). The management literature has found that Italian public utilities such as those analyzed in this study are slowly but surely increasing the use of these systems (Gandini, 2004). This trend is probably driven by the need to manage more increasingly complex decisional processes and pay greater attention to cost-effectiveness (Martinez et al., 2015).

Aim and research questions

This study analyzes if a sample of state-owned Italian companies operating in the waste sector has identified and managed sustainability goals using advanced management tools that allow them to translate strategic objectives into action. The proper management of economic, social, and environmental issues can enable the provision of high-quality services that are environmentally friendly and respectful of the local community’s needs.

First, the study investigated if the companies identified strategic goals that were sustainability-oriented and then if they used strategic planning tools to translate the sustainability goals into operational terms. The research focused on the following strategic planning tools:

i) Business performance models (Balanced Scorecard, strategy map, tableau de bord, Skandia Navigator);

ii) Strategic plans;

iii) Economic and financial planning documents;

iv) Performance indicators (both financial and non-financial);

v) Business Process Improvement (BPI), Business Process Reengineering (BPR), or tools to support the review of strategic programs;

vi) Other management tools (e.g., Integrated Reporting, Target Costing, Differential Reasoning).

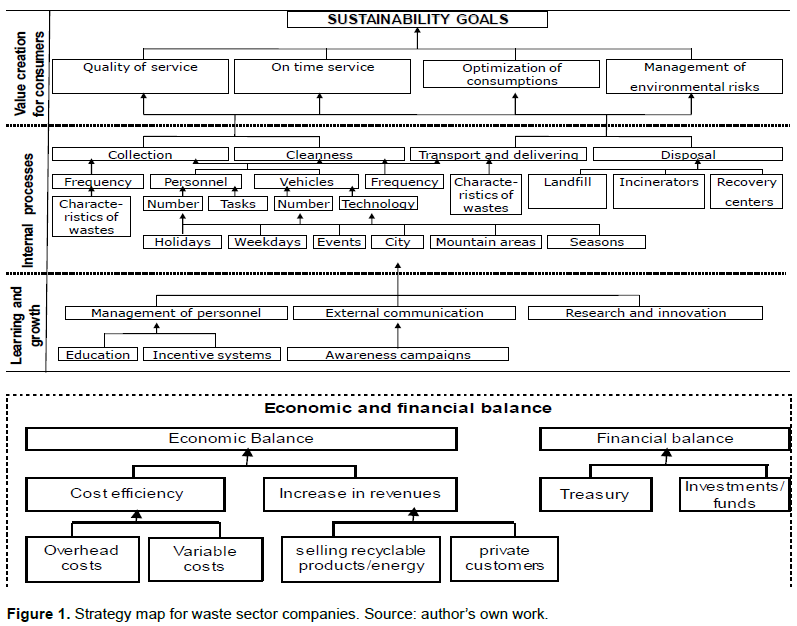

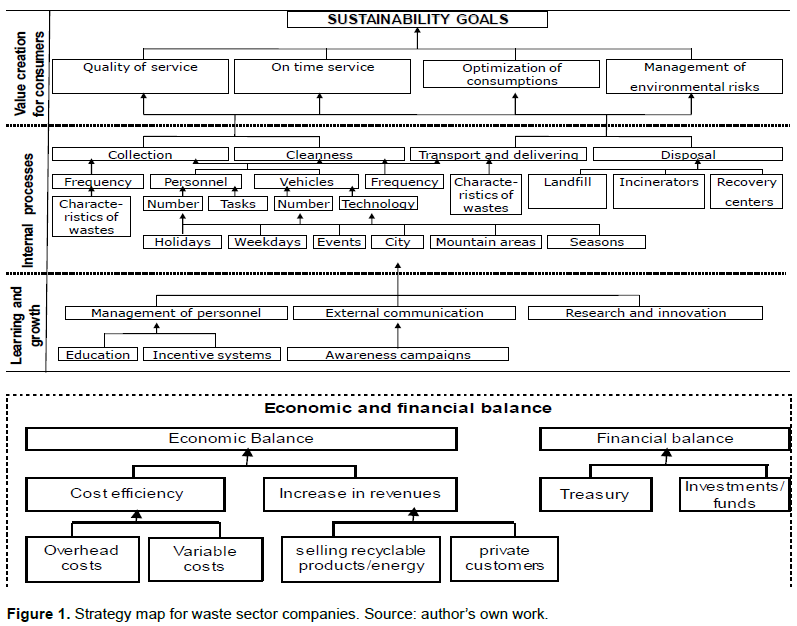

Based on analyses of internal documents and interviews, the study drew up a proposal for a business model that translates the companies’ strategy into a coherent set of drivers according to social and environmental patterns. The business model follows the logic of the strategy map (Kaplan and Norton, 2004) because, to a greater extent than other strategic planning tools, it provides a language by which companies can describe their strategy, highlighting the cause-and-effect relations among the key success variables. The proposed business model is intended as a guide, not an inflexible framework, and must be adjusted according to the organizational structure and distinctive key variables involved.

This research began at the end of 2010 and concluded its first stage in 2012. At the end of this period, the results and a draft of the business model were presented to the interviewed companies. Their feedback allowed us to refine the logic and the drivers of the strategy map. During the second phase, concluded in 2015, we kept in touch with the companies in order to verify changes in the sustainability orientation or in the use of the strategic planning tools. This enabled the formulation of a more accurate version of the strategy map. No consulting relationships with the companies were established during the research process. The main research questions were as follows:

RQ1: Do strategic goals include the sustainability issue? Have they changed over time (from 2012 to 2015)?

R.Q.2: What are the main strategic planning tools adopted by companies to manage strategic goals, how has the use of these tools changed over the years (from 2012 to 2015)?

Approach

The research was conducted through the case study method, a qualitative approach where theory and empirical research are intertwined. Although this method is somewhat subjective and is often criticized for a lack of statistical reliability and validity, it is especially useful when it is necessary to understand a complex issue (Yin, 1994). It can also develop expertise and reinforce what is already known through previous research. While the conclusions reached from a single case study may be uncertain, the use of multiple cases enhances their robustness (Robson, 1993; Yin, 1994). Scapens (1990) notes the importance of case studies for understanding reality. This study used a qualitative method and performed a multiple case study analysis because examining sustainability strategies and their implementation is a complex task, and it is not possible to analyze internal dynamics through a quantitative method.

This study’s data collection drew from multiple sources of evidence, which allowed us to increase the validity of our constructs (Yin, 1994). The sources included semi-structured interviews with key respondents (top and middle-level managers of strategic, financial, and technical units), industrial reports, strategic planning reports, annual reports, technical and non-technical documents, and project reports. The interviews lasted between one and three hours and included questions intended to verify the quality of the answers. The questions were on both general and specific topics such as the peculiarity of the business, the strategy orientation and role of sustainability, the features of the strategic planning process and related tools, the indicators being monitored, the main stakeholders, the role of the environment in the company’s management, and the external communication process. The interviews were useful for understanding the peculiarities of the strategic planning tools used and identifying the critical success factors of the businesses, together with their cause-and-effect relations. A draft of the results was sent to all interviewees for their comments and to ensure that the technical details were interpreted correctly, which, according to Yin (1984), ensures construct validity.

The interview has advantages as a survey tool, such as its ability to provide flexibility, capture nonverbal behavior, allow environmental control, change the order of questions, enable completeness, and obtain responses from interested interviewees, but it has also disadvantages such as its costs and time consumption, the interviewer’s influence on respondents, and its lower degree of question standardization. Consequently, interviews were semi-structured in order to keep them within the main question areas while allowing the interviewees to offer their own opinions. According to Yin (1984), open-ended interviews can expand the depth of data gathering and increase the number of information sources. We did not use the questionnaire as a survey tool because it would not have allowed us to verify if respondents knew much about the company’s strategy and implementing dynamics; practical insights into the possibilities and problems concerning those issues were needed in qualitative terms.

The sample

The sample comprises 10 state-owned enterprises whose shareholders are local municipalities located in the Piedmont and Lombardy regions of Italy’s northwest. Piedmont and Lombardy are among the most committed regions in Italy regarding waste prevention, environmental impacts, and separated collection (ANCI and CONAI Report, 2015). Enterprises were selected from the Italian Register of Environmental Managers, based on business area and firm size. Several dimensions were used as discriminating factors: only companies offering services to more than 100,000 people and that were located in larger cities were considered. The selected cases are representative because they operate in regions that take particular care of their environment and local community and provide services to a significant number of users. In addition, the companies analyzed were chosen on the basis of several shared features: their public nature, the typology of their waste collection services (both recyclable and non-recyclable), their transport to disposal centers and its management, and their urban hygiene services. The sample firms also offer secondary urban hygiene services in the municipalities where they operate.

This section focuses on intra-organizational factors, particularly the sustainability goals and management tools that make the strategic orientation effective.

Sustainability goals

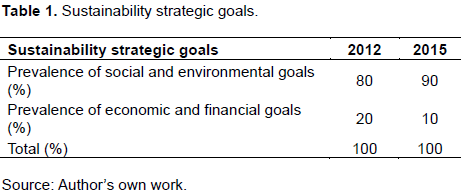

First, RQ1 was investigated through the interviews and internal documents; the goal was to determine if environmental and social aspects were prominent within the strategic goals. The results, shown in Table 1, include both the historical results, obtained during the first stage of the research (completed in 2012), and the updated results (obtained in 2015).

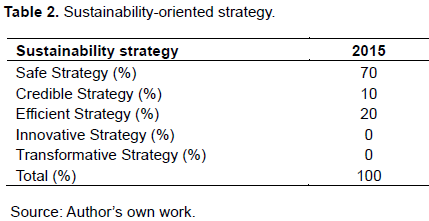

A sustainability orientation is widespread within the companies in both 2012 and 2015. Indeed, companies in which social and environmental goals are crucial topics represent 80% of the sample in 2012 and 90% in 2015. A minority of companies shows a preponderance of economic and financial strategic issues. Only one company in 2012 and two companies in 2015 have formalized a strategy; in the remaining cases, a strategy has been deliberated and is well-known at the top-management level but is not formalized in a document. Using the classification of Bieker et al. (2002), we then analyzed the strategic orientation in 2015.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of a strategy oriented to managing and reducing risks, with a focus on environmental risks, followed by an “efficient” strategy aiming to improve “eco-efficiency” and “socio-efficiency” (Wackernagel and Rees, 1996; Dyllick and Hockerts, 2002) and a “credible” strategy of preventing conflicts with authorities and other stakeholders. Next, the study investigated if the strategic goals were translated into operational terms.

Diffusion of strategic planning tools

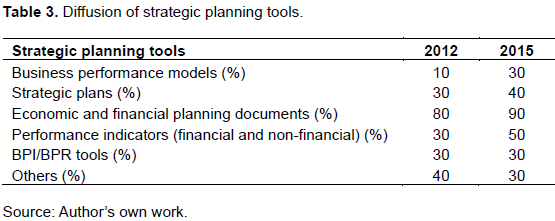

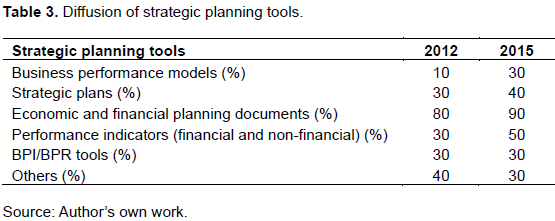

The second research question examines the diffusion of strategic planning tools within the state-owned enterprises. The tools analyzed are business performance models, strategic plans, economic and financial planning documents, performance indicators (both financial and non-financial), Business Process Improvement (BPI)/ Business Process Reengineering (BPR) tools, and others (e.g., integrated reporting, target costing, differential reasoning). Table 3 shows the results for 2015.

The results show little diffusion of advanced management control systems; however, a positive trend emerges between 2012 and 2015. In 2012, only one company uses a business performance model comparable to the tableau de bord (Lanzel and Cibert, 1962); in 2015, one company continues to use the tableau de bord and two companies use the strategy map following the framework suggested in the next section. The CFO of a company that uses the strategy map declared as follows: “I think that this business model is a powerful tool that offers an integrated and complete vision of our company but unfortunately in the coming years we’ll probably abandon this tool as it is too expensive. The financial constraints imposed by the municipality which is also our main shareholder force us to make heavy cuts especially in administrative and staff areas. This is because we don’t want to penalize the service and consequently the final users.”

Use of the strategic plan has increased from 30 to 40%, and economic and financial planning documents are widespread within the companies. It was decided to differentiate the strategic plan from the economic and financial planning documents because, after analyzing these types of documents in depth, we found that some of the documents labeled “strategic plan” were actually just financial plans. The systematic use of financial and non-financial indicators has increased over time, while the use of BPR/BPI systems has remained stable. Conversely, use of the other managerial tools that can be employed to support strategy implementation has decreased. No company has ever used integrated reporting or target costing; only differential reasoning has been used.

Strategy map

The interviews and internal document analysis revealed little diffusion of management tools for aligning organizational units to strategy. One useful framework for describing and communicating a strategic plan is the strategy map (Kaplan and Norton, 2001, 2004), which can bridge the gap between strategies and action plans. The business model is built following the logic of the strategy map because it highlights the cause-and-effect relations among the key success variables of a strategy better than other strategic planning tools. Based on information and suggestions obtained through the interviews and documents analysis, four perspectives were identified and adapted to the peculiarities of the sector:

i) Value creation for consumers (end users): the key success factors necessary to maximize the public utility;

ii) Internal processes: the critical internal process in which the company excels;

iii) Learning and growth: the employees’ skills, the companies’ communication campaigns, and the investments in research and innovation;

iv) Economic and financial balance: the economic and financial goals necessary to optimize costs, reduce the financial intervention of public administration and banks, and apply the fairest price to final users.

Figure 1 shows the strategy map, highlighting the strategic environmental and social objectives. Companies should adapt the proposed model according to their specific needs and activities. The proposed strategy map identifies the key success factors that could be considered common among the companies analyzed. The arrows of effects proceed from the lower perspectives to the higher ones, while the arrows of strategic interference (which are not explicitly drawn in the map) proceed from the higher perspective to the lower ones. The perspectives are logically, rather than mathematically, related. The economic and financial perspective is presented separately because it influences the other perspectives while also being influenced by them. The economic and financial aspects are relevant to publicly owned enterprises, but they represent a constraint, not a final goal, because their management is focused on creating public utility rather than profits. Companies have to deal with the scarcity of resources and manage them efficiently and effectively in order to achieve excellence.

Starting with the highest perspective, the basic objectives of management are orientated toward the creation of value for final users (citizens). Such value creation can be attained through on-time service with high-level quality. It can also derive from an optimization of resource consumption in an attempt to reduce the environmental impacts generated by company activities or an appropriate management of environmental risks in order to protect the firm’s area of operations and the health of residents. These key success factors enable companies to reach their environmental goals and enhance the wellbeing (quality of life) of local communities.

The second perspective concerns the internal processes in which the organization excels. The map highlights the critical processes which, if managed efficiently and effectively, will enable the organization to ultimately reach the goals of the first perspective. Based on the companies’ similarities, the critical processes concern collection (on public property or in private buildings), transport and delivery, the management of disposal centers, and urban cleaning.

The third perspective identifies the infrastructure that companies must build to create long-term growth and foster learning. This perspective takes into consideration the intangible assets of employee management, external communication, and research and innovation. One key variable is represented by the campaigns undertaken to communicate the new initiatives directed at the area of operations and intended to engage citizens in the companies’ goals and policies. These are powerful tools that help build trust and partnerships with the local community. The last intangible asset is research for technological innovation, which requires cooperation with suppliers and research centers in order to find the best technological solutions with the least environmental impact.

This study conducts a longitudinal analysis on how the sustainability issue can be a guiding principle used to define long-term goals and day-to-day activities, focusing on Italian state-owned companies in the waste sector. Many studies (Adams and Frost, 2008; Epstein and Buhovac, 2014; Epstein and Roy, 2001; Figgie et al., 2001; Schaltegger and Burrit, 2000; O’ Connor, 2006; Schaltegger et al., 2012) have investigated the presence of social and environmental concerns in strategic goals. Our results show a high sustainability orientation in the sample, though too often these objectives are not formalized or communicated to the lower levels of the organization. The most prevalent strategy focuses on the prevention of harmful effects linked to behavior inconsistent with sustainability (Bieker et al., 2002).

Attention then turned to the strategy implementation tools that allow the execution of the sustainability goals. As has been observed in the literature (Martinez et al., 2015), these tools are not particularly widespread in the sample. The most advanced systems, business performance models, are used by only 30% of the sample (and one company will probably abandon the strategy map because it is too expensive). On the other hand, financial plans are widespread. However, if such plans are not linked to the strategic goals and other managerial systems, they can lose their strategic significance because they will fail to consider the variables that can affect the results. However, over the years, a positive trend emerged, as was observed by Gandini (2004). The limited diffusion of advanced managerial systems encouraged us to build a business model based on the logic of the strategy map that directly reflects the companies’ strategy and considers the crucial problem of the alignment of different organizational units.

As suggested by many authors (Butler et al., 2011; Brusa, 2007; Epstein and Wisner, 2001; Figgie and Hahn, 2004), the four perspectives of the strategy map, suitably adapted to the peculiarities of the sector, include sustainability-related issues. According to Brusa (2007), the economic and financial perspective does not represent the main goal of a company. Indeed, the basic objectives of management should be oriented toward the creation of value for final users (citizens), which can be attained via on-time service with high quality standards. In accordance with the main literature (Epstein and Buhovac, 2014; Schaltegger and Wagner, 2006; Figge et al., 2002; Dias-Sardinha and Reijnders, 2001), the three pillars of sustainability are apparent at this stage in the will to i) optimize resource consumption and financial factors (economic); ii) rethink techniques and processes in order to improve service features and protect the area of operations and residents’ wellbeing (social); and iii) reduce the environmental impact (environmental). This map could be a valid framework for companies operating in the waste sector as a way to trace the indicators necessary to monitor performance, but it must be adapted to the company’s needs, mission, culture, and goals.

This study has several theoretical and practical implications, as it extends the literature on sustainability and strategic planning tools in public utilities companies, filling a gap that has been highlighted in the literature (Northcott and Taulapapa, 2012). The main limitation of this work derives from the research method chosen. The analysis of a limited number of companies does not allow statistical generalization. However, a qualitative investigation was necessary to understand fully how sustainability goals are integrated within the organizations. Future research could extend the number of case studies in order to validate our results, and also include private service providers in the waste sector to examine if a change in sustainability orientation occurs in the diffusion of strategic planning tools and in the features of the strategy map.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adams CA, Frost GR (2008). Integrating sustainability reporting into management practices. Accounting Forum. 32(4):288-302.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Associazione Nazionale Comuni Italiani (ANCI) and Consorzio Nazionale Imballaggi (CONAI), 5th ANCI-CONAI report on waste collection and recycling,

View

|

|

|

|

Bieker T, Dyllick T, Gminder CU, Hockerts K (2001). Towards a sustainability balanced scorecard – linking environmental and social sustainability to business strategy. Proceedings 10th Business Strategy and the Environment Conference, 22-31.

|

|

|

|

Bieker T, Dyllick T, Gminder CU, Hockerts K (2002). Towards a Sustainability Balanced Scorecard. Linking Environmental and Social Sustainability to Business Strategy. St. GallenFontainebleau: Publication of IWÖ-HSG and INSEAD.

|

|

|

|

Boston J, Martin J, Pallot J, Walsh P (1996). Public Management: The New Zealand Model, Auckland: Oxford University Press.

|

|

|

|

Boyce G (2000). Public discourse and decision making: exploring possibilities for financial, social and environmental accounting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 13(1):27-64.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Brusa L (2007). Attuare e controllare la strategia aziendale – Mappa strategica e Balanced Scorecard, Milano: Giuffrè.

|

|

|

|

Butler JB, Enderson SC, Raiborn C (2011). Sustainability and the balanced scorecard: integrating green measures into business reporting. Manage. Account. Quart. 12(2):1-10.

|

|

|

|

Dias-Sardinha I, Reijnders L (2001). Environmental performance evaluations and sustainability performance evaluation of organizations: an evolutionary framework. J. Corporate Environ. Manage. 8(2):71-79.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dias-Sardinha I, Reijnders L, Antunes P (2002). From environmental performance evaluation to ecoefficiency and sustainability balanced scorecards. Environ. Qual. Manage. Winter: pp. 51-64

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dias-Sardinha I, Reijnders L (2005). Evaluating environmental and social performance of large Portuguese companies: a balanced scorecard approach. Business Strategy Environ. 14(2):73-91.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dias-Sardinha I, Reijnders L, Antunes P (2007). Developing sustainability balanced scorecards for environmental services: a study of three large Portuguese Companies. Environ. Qual. Manage. Summer. pp. 13-35

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dyllick T, Hockerts K (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability, Bus. Strategy Environ. P 11.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Elkington J (1997). Cannibals with forks: the triple bottom line of 21st century business, Oxford: Capstone.

|

|

|

|

Epstein M, Manzoni JF (1998). Implementing corporate strategy: from tableaux de bord to Balanced Scorecard. Eur. Manage. J. 16(2):190-203.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Epstein MJ, Roy MJ (2001). Sustainability in action: identifying and measuring the key performance drivers. Long Range Plan. 34(5):585-604.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Epstein MJ, Wisner PS (2001). Implementing Social and Environmental Strategies with the Balanced Scorecard. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

|

|

|

|

Epstein MJ, Buhovac AR (2014). Making sustainability work: Best practices in managing and measuring corporate social, environmental, and economic impacts, Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

|

|

|

|

Figgie F, Hahn T, Schaltegger S, Wagner M (2001). The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard – a tool for value oriented sustainability management in strategy-focused organizations. Conference Proceedings of the 2001 eco-management and auditing conference, ERP environment, Shipley, pp. 83-90.

|

|

|

|

Figge F, Hahn T, Schaltegger S, Wagner M (2002). The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard—linking sustainability management to business strategy. Business Strategy & the Environment, September/October: 269-284.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Frost G, Seamer M (2002). Adoption on environmental reporting and management practices: an analysis of New South Wales public sector entities. Financial Accountability Manage. 18(2):103-27.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Fülöp G, Hódi HB (2012). Corporate sustainability – strategic alternatives and methodology – implementation. Management, Knowledge and Learning International Conference, 20-22 June 2012, Celje, Slovenia, 109-120.

|

|

|

|

Gandini G (2004). Internal auditing e gestione dei rischi nel governo aziendale, Milano: Franco Angeli.

|

|

|

|

Gray R, Dillard J, Spence C (2009). Social accounting research as if the word matters. Public Manage. Review. 11(5):454-573.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Greiling D, Grüb B (2014). Sustainability reporting in Austrian and German local public enterprises. J. Econ. Policy Reform. 17(3):209-223.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hansen EG, Schaltegger S (2016), The sustainability balanced scorecard: A systematic review of architectures. J. Bus. Ethics. 133(2):193-221.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hood C (1995). The new public management in the 1980s: variations on a theme. Account. Organ. Society. 20(2/3):93-100.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA), Rapporto sui rifiuti urbani, ed. 2015, available at http://isprambiente.gov.it

|

|

|

|

Jackson A, Lapsley I (2003).The diffusion of accounting practices in the new managerial public sector. Int. J. Public Sect. Manage. 16(4/5):359-372.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kaplan RS, Norton DP (1992). Balanced scorecard – measures that drive performance. Harvard Bus. Rev. 70(1):71-79.

|

|

|

|

Kaplan RS, Norton DP (1996). Using the Balanced Scorecard as a strategic management system. Harvard Bus. Rev. 74(1):75-85.

|

|

|

|

Kaplan RS, Norton DP (1996). Translating strategy into action. The Balanced Scorecard, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

|

|

|

|

Kaplan RS, Norton DP (2000). Having trouble with your strategy? Then map it. Harvard Bus. Rev. 78(5):167-276.

|

|

|

|

Kaplan RS, Norton DP (2001). The strategy focused organization, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

|

|

|

|

Kaplan RS, Norton DP (2004). Strategy map, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

|

|

|

|

Lapsley I, Wright E (2004). The diffusion of management accounting innovations in the public sector: a research agenda. Manage. Account. Res. 15(3):355-374.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Line M, Hawley H, Kurt R (2002). The development of global environmental and social reporting. Corporate Environ. Strategy 9(1):69-78.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Martinez M, Iacono MP, Galdiero C, Mercurio R (2015). Public-private partnerships in the Italian Healthcare Sector: the analysis of organizational forms. In Toulon-Verona Conference" Excellence in Services".

|

|

|

|

Maruccio M, Steccolini M (2005). Social and environmental reporting in local authorities. A new Italian fashion?. Public Manage. Rev. 9(2):155-176.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Moller A, Schaltegger S (2005). The sustainability balanced scorecard as a framework for eco-efficiency analyses, J. Ind. Ecol. 9(4):73-83.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Northcott D, Taulapapa TM (2012). Using the balanced scorecard to manage performance in public sector organizations: issues and challenges. Int. J. Public Sector Manage. 25(3):166-191.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Nidumolo R, Prahalad CK, Rangaswami MR (2009).Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation. Harvard Bus. Rev. 87(9):56-64.

|

|

|

|

O'Connor M (2006). The four spheres framework for sustainability. Ecol. Complexity 3(44):285-92.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Perera S, McKinnon JL, Harrison GL (2003). Diffusion of transfer pricing innovation in the context of commercialization: a longitudinal case study of a government trading enterprise. Manage. Account. Res. 14(2):140-64.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Robson C (1993). Real World Research, Oxford: Blackwell.

|

|

|

|

Scapens RW (1990). Researching management accounting practice: the role of case study methods. Br. Account. Rev. 22:259-281.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Schaltegger S, Burrit R (2000). Contemporary environmental accounting: issues, concepts and practice, Greenleaf: Sheffield.

|

|

|

|

Schaltegger S, Wagner M (2006). Integrative management of sustainability performance, measurement and reporting. International Journal of Accounting, Audit. Perform. Evaluation 3(1):1-19.

|

|

|

|

Schaltegger S, Lüdeke-Freund F, Hansen EG (2012). Business cases for sustainability: the role of business model innovation for corporate sustainability. Int. J. Innovat. Sustain. Dev. 6(2): 95-119.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sidiropoulos M, Mouzakitis Y, Adamides E, Goutsos S (2004). Applying sustainable indicators to corporate strategy: The eco-balanced scorecard. Environmental Research, Engineering and Management, 1(27):28-33.

|

|

|

|

Smith M (2005). The balanced scorecard. Financial Management, February: 27-28.

|

|

|

|

Vagnoni E (2001). Social reporting in European health care organizations: an analysis of practices. Paper presented at the third Asian pacific interdisciplinary research in accounting conference, University of Adelaide, Australia, July.

|

|

|

|

Yin RK (1984). Case study research: design and methods, Beverly Hills: Sage publications.

|

|

|

|

Yin RK (1994). Case Study Research Design and Methods. 2nd ed., Applied Social Research Methods Series, Sage, Volume 5.

|