ABSTRACT

Due to its effect on both individual outcomes like job mobility, job satisfaction, job involvement and fair remuneration on the one hand and organizational outcomes like employees’ attendance, turnover, cynicism and performance on the other, diversity has become a rising trend more than ever before. The concept is no longer limited to Western countries but has become popular in many parts of the world. This study focuses only on Kasr El Eini hospital and in an attempt to investigate how nurses perceive their diversity. 25 semi- structured interviews were conducted, and the findings reflect that nurses at Kasr El Eini hospital, like many other classes of Egyptian society, struggle in a state of division and lack the value of inclusion in their workplace. Moreover, distributive justice was perceived with doubt by nurses there. The study ends with the recommendation that managers at Kasr El Eini hospital establish a professional identity for the hospital in which the concept “good colleague” should be utilized. Furthermore, paying attention to both inclusion and justice is also a needed mechanism there.

Key words: Diversity, diversity management, affirmative action, in- out group differentiation, inclusion, justice, Egypt.

Owing to local and global uncertainties and interaction among people with different origins, backgrounds and beliefs, cultural diversity has become a rising trend (Devine et al., 2007; Mazur and Bialostocka, 2010). Its existence is no longer limited to western countries like the USA and UK as many countries in different parts of the world have become familiar with it.

However, it is worth highlighting that both public and private organizations in the context of western countries have had a long history in designing and implementing diversity policies with the aim of ensuring a fair representation for minorities in the workplace (Ashikali and Groenveld, 2015).

Since 1960, the concept of cultural diversity has gained currency in academic research. This has happened as a result of the adoption of some affirmative actions promulgated by the U.S government to eliminate racial discrimination in organizations and universities (Tereza and Fluery, 1999).

Reportedly, initial efforts to address cultural diversity have focused mainly on gender and race (Morrison et al., 2006). However, and as a response to the social, political, educational and economic changes occurring in both the local and global environments, the term “cultural diversity” has markedly expanded to include gender, race, religion, ethnicity, income, work experience, educational background, family status and other differences that may affect the workplace (Heuberger et al., 2010).

Cultural diversity refers to the co- existence of people with various group identities within the same organization (Humphrey et al., 2006). Kundu (2001) indicates that diversity requires the inclusion of all groups of people at all organizational levels. The issue requires an organizational culture in which each employee can utilize his/ her full capacity to attain career aspirations without being hobbled on the basis of religion, ethnicity, name, gender or any other irrelevant factor (Alas and Mousa, 2016).

That is why, Cox (1991) clarifies that any effective management for culturally diverse groups should entail the attainment of both individual outcomes (job satisfaction, job mobility, job involvement and fair remuneration) and organizational outcomes (attendance, turnover, performance and consequently profit).

Moreover, Pless and Maak (2004) assert the role of diversity management in creating an inclusive organizational climate in which employee uniqueness is acknowledged, maintained and valued while also feelings organizational citizenship and normally identification with the workplace. Therefore, under the umbrella of diversity management and its inclusive organizational climate, every employee is treated as an insider and experiences a kind of mutual trust with his organization (Nishii, 2013).

Kasr El Eini is the first and largest governmental medical school and hospital in Egypt. (http://www.medicine.cu.edu.eg/beta1/index.php/en/). It was established in 1827 in a region called El Manial Island, Cairo. According to its website, Kasr El Ein includes 2773 medical professors and physicians, 3732 post-graduate students, and 9423 students. This medical school and hospital has the mission of graduating quality physicians capable of implementing various levels of health care practices. The school and hospital management are concerned with the development of a competitive human capital that would serve the community and share in solving national health problems. Kasr El Eini is currently the focus of the Egyptian media, politics, and public discourse because of the many difficulties that both physicians and patients face. The majority of its nurses are facing the problem of low involvement and low participation. A famous Egyptian newspaper and website called al3asma has published an investigation to explore the aspects of this dilemma (http://www.al3asma.com/40137). Many Kasr El Eini nurses claim that besides their low salaries, the hospital is full of managerial corruption, bias, inequality and nepotism (www.albawabhnews.com/2419159).

Owing to the fact that Kasr El Eini is the main destination for Egyptian low and middle income families (www.elwatannews.com/news/details/1255899) and that the increase of nurses’ irritation is an undisputed fact that may hinder their performance, engagement, and loyalty, this research seeks to fill in a gap in management literature by seeking an answer for the question of how nurses at Kasr El Eini hospital perceive their diversity.

The study starts by giving a comprehensive description of what diversity and diversity management are besides highlighting the theories based upon which diversity can be traced. Next, it elaborates the position of women in Egyptian national culture and seeks to touch on the struggles which women are experiencing there. Thirdly, the study shows the methodology part in which the author indicated how he chose his sample, context, and pro-cedures to conduct and then analyze interviews. Fourthly, the answer of the research question is introduced, and fifthly, the conclusion conveys implications for managers and researchers who may have interest in further investigating the same question or researching the same phenomena.

This study is significant not only because it is, to the best of the researcher knowledge, considered the first to qualitatively investigate diversity perception experienced by a specific category of public employees in Egypt but also because it comes after media coverage of several accidents, which includes church bombings in Egypt and forced migration of a number of Christians from the cities in which they used to live.

Admittedly, there is a national cold peace between Muslims and Christians even though the Egyptian political regime has decided to neglect the issue for the time being. This research takes a closer look to Egyptian workplace harmony by investigating relationships between Muslim and Christian nurses at a section of the biggest public hospital in the country.

It is worth mentioning that a previous quantitative study by Mousa and Alas (2016a) has examined the relationship between cultural diversity challenges (communication, discrimination and training) and organizational commitment of teachers in Egyptian public schools. However, and despite the significance of its findings, it has no direct relevance to the present qualitative study.

Diversity and diversity management

Given the desire to ensure a fair representation for minorities such as women, Hispanics, Indians and also handicapped people, research about cultural diversity started in the USA with the end of 1960s (Zanoni et al., 2009). The first studies about cultural diversity aimed to control the racial discrimination existing in organizations and teaching places as a step towards cultivating the social coherence inside American enterprises (Dogra, 2001).

In 1986, Canada did the same by launching the employment equity act program which was seeking to enhance a fairer employment system, understand the constraints faced by ethnic minorities and women in the workplace, and also ensure a fair numerical representation of minorities in different Canadian organizations (Agocs and Burr, 1996).

It is needless to say that many other countries like Malaysia, India, Britain and South Africa acted in the same way by facing the cultural discrimination existing in both their public and private businesses (Jain, 1998). It is needless to say that changes in worldwide labor markets besides the tremendous economic investment motivation packages launched by many countries and simultaneously the rising intensive role of multinational corporations have contributed a lot to addressing the topic of diversity and diversity management.

Primarily, it is important to define both culture and diversity separately before going into further details. Culture means “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005) whereas diversity points out the case of being different. The concept diversity stems its roots from a Latin word called “diversus” which means different directions (Sinclair, 1999) according to Vuuren et al. (2012).

According to Hassi et al. (2015) diversity reflects the synergetic existence of differences in age, ethnicity, background, sex and disability. Moreover, Vuuren et al. (2012) define cultural diversity as “the differences in ethnicity, background, historical origins, religion, socio-economic status, personality, disposition, nature and many more”.

Tereza and Fleury (1999) consider cultural diversity to be “a mixture of people with different group identities within the same social system”. O’Reilly et al. (1998) mention that “a group is diverse if it is composed of individuals who differ on characteristics on which they base their own social identity”. Consequently, cultural diversity gives a real indication for world competition and workforce pool nowadays. Loden and Rosener (1991) classify diversity into the following two dimensions:

1. Primary dimensions: shape people self-image such as gender, ethnicity, race, age, sexual orientation and physical abilities.

2. Secondary dimensions: include characteristics that affect people’s self-esteem such as religion, education, income level, language, work experience and family status.

Besides the primary and secondary dimensions of diversity, Rijamampianina and Carmichael (2005) add concepts such as assumptions, values, norms, beliefs and attitudes as a third dimension of diversity. Although the discourse on cultural diversity started in the USA by focusing on differences in ethnicity and gender, it now goes beyond this narrow range to include differences among individuals (tall, short, thin, bald, blonde, intelligent, not so intelligent, and so on) and differences among subgroups in terms of age, sexual preferences, socio-economic status, religious affiliations, languages, and so on (Kundu, 2001; Vuuren et al., 2012).

Humphrey et al. (2006) consider any society as constituted of a diverse range of groups that have diverse needs. Diversity policies constantly seek to create and maintain fairness and representation in various work-places and, as such, diversity programs which employed both affirmative action and equal employment opportunity to ensure minority representation in workplace have been replaced by policies that pay attention to the business case of diversity. Consequently, diversity policies can lately be considered a vital part of human resources management policies (Ashikali and Groenveld, 2015).

Concerning the advantages of cultural diversity, Hubbard (2011) indicate that building a business case for diversity guarantees a better access to new markets, complete and detailed awareness of current markets, better problem solving dynamics, better attraction and retention of talent and enhanced entrepreneurship and creativity levels.

Moreover, Humphrey et al. (2006) stress that educating people to appreciate cultural diversity entails a support for the values of tolerance and solidarity. Countries can’t mirror any democratic norms without promoting respect for diversity and its corresponding values of freedom, equality, and inclusion.

In different perspective, Singal (2014) highlights that a diversity of workplace may be accompanied by increasing costs of training, communication, coaching and managing conflicts. Moreover, forming and maintaining trust between managers and influx of diverse employees is often a challenge. Some studies claim that diversity may hurdle synergy between groups, lead to confusion and thus negatively affect participation especially of people belonging to minorities, the aspect that hinders some groups’ attendance, loyalty and consequently productivity (Tsui et al.,1992; Cox, 1993; Mousa and Alas, 2016).

Admittedly, diversity management reflects an acknowledgement and respect for employee differences throughout organizations (Wrench, 2005). In Hudson institute, a publication titled “workforce 2000: work and workers in the 21st century” discusses women’s active participation and demographic changes in labor market and ends by highlighting that diversity management has been proved to be a key asset on which organizations can depend to attain a competitive advantage in such a climate of multiculturalism (Johnston and Packer, 1987).

Traditionally, and in order for instill organizational justice, diversity management has depended on both affirmative action programs to redress all past discrimination and inequality acts and equal employment opportunity programs to ensure heterogeneity at the workplace through legislations, rules and laws. Noticeably, diversity management may be linked to the following two human resources management theories:

1. Social identity theory: Tajfel (1978) considers that social identity theory has come to be a result of previous research on stereotype and prejudice and is considered a shift from individual to group-level analysis of psychological research. The theory claims that individual identity is supported by belongingness to a particular group as it creates much more self-esteem for its members. Accordingly, people feel belongingness to their in-group members and have negative attitudes towards their out- group members. For instance, in male- dominated societies men have higher positions than women because of their belonging to the higher-status group (males). Breakwell (1993) indicates that this theory not only explains intergroup relationships but also reflects individual tendency to create a positive social identity. That’s why, Tajfel (1978) elaborates that the main mission of social identity theory is to interpret intergroup conflict and differentiation.

2. Social exchange theory: is one of the most important theories in explaining workplace behavior. Therefore, it can be touched on in various organizational and managerial topics such as psychological contract, organizational justice, board independence and responsible leadership (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005). Fao and Fao (1974) identifies that love, status, money, information, goods and services are considered the six types of resources included in employer- employee relationship. According to this theory, when an employer cares about his/her employee and this employee perceives fair treatment from his/her employer, the later subsequently does his/her best to fulfill organizational objectives, and he/she constantly has a positive attitude towards his employer.

According to Devine et al. (2007) and Mousa and Alas (2016b), for the effective management of cultural diversity, organizations should overcome the following three main challenges. First, communication is considered an important mechanism through which employees acknowledge what is required of them, how to implement their jobs and what feedback is produced for them and others in the workplace.

Barrett (2002) considers communication as a means not only for explaining organizational strategy but also for motivating employees to accomplish their jobs. In the area of cultural diversity, the significance of communication stems from its ability to entail a kind of transparency as employees feel justice when ex-periencing an open communication policy concerning their job responsibilities and feedback reports. Moreover, communication facilitates the creation and maintenance of formal anti-discrimination complaint procedures (Siebers, 2009a).

Egyptian women and cultural diversity

With a population of 92 million and a geographic location extending between Africa and Asia, Egypt – the country that stretches from Mediterranean Sea in the north to Sudan in the south, Gaza strip in the east and Libya in the west – is constantly considered one of the leading countries in Africa, the Middle East and the Arab region.

Noticeably, this country has a historical extended economic and political relationship with many, if not all, Mediterranean and European countries, the matter that promotes the deep and comprehensive free trade agreement (DCFTA) (Caiazza and Volpe, 2015) to support the Egyptian economic reform launched. Mousa and Alas (2016); Mousa and Abdelgaffar (2017), claim that uncertainty may be seen currently as a main feature of both Egyptian economic and political scenes, whereas Hofstede and Hofstede, (2005) indicates that religion is considered the main determinant of Egyptian culture nowadays.

Moreover, a study made by Hofstede and Hofstede, (2005) asserted the existence of the following four main dimensions in creating and shaping the Egyptian culture:

1. Power distance: reflects the complete acceptance of Egyptian citizens to the unquestionable power their leaders have.

2. Uncertainty avoidance: reflects not only the complete acceptance of Egyptian citizens for their fate but also their tendency to curb and reject any potential tension or intention to change.

3. Individualism: reflects the strong influence for the Egyptian family on individual’s behavior and values, and individual’s loyalty to such domination.

4. Masculinity: reflects the superiority men have within the Egyptian society. This superiority stems, to a big extent, from the Islamic traditions.

However, and given the results of Alas and Mousa (2016); Mousa and Alas (2016c), it is evident that social norms also play a tremendous role in shaping Egyptian culture which considers the man as the head of the family, the main breadwinner, and the dominant voice in the family, and the woman as obedient to her husband and responsible for raising children and household duties.

Moreover, it is noticeable that Egyptian society accepts women basically for the positions of healthcare, teaching and office support. Therefore, Egyptian women face many phenomena of discrimination in spite of the governmental approval of family and personal status laws to alleviate discrimination against women (UN Report, 2007).

To the best of the researcher’s knowledge, there is no official indicator clarifying the number of employed/ unemployed, abled/disabled, educated/uneducated and single/parent women in Egypt. However; there are growing social and media debates concerning women’s early marriage, leave to education, and subsequently low participation level in workplace. Such debate emanates from demographic changes, socio-economic development and human right reform.

The research process started in 2016 by gathering all the relevant literature on cultural diversity, as well as its management. As mentioned earlier, the researcher found numerous studies covering the topic of cultural diversity.

However, all of these studies may be divided into three categories. The first category focuses on identifying cultural diversity in either public or private settings. The second category examines how employees perceive and experience it in a specific organizational setting. The third category mostly focuses on determining the consequences of the absence of the effective management of diversity in a specific workplace. Admittedly, what has been noted is the absence of research into cultural diversity in African and Middle Eastern countries.

Furthermore, and to the best of the researcher’s knowledge, challenges to diversity have not been addressed before in the previously mentioned regions. The search for previous studies on cultural diversity extended for more than 6 months, and the search process occurred in both English and Arabic – languages the author can manage.

This study decided to conduct an exploratory case study to comprehensively yield as much information as possible since not much is known about diversity in various Egyptian work settings. The study chose to focus only on Kasr El Eini hospital.

It is needless to say that case study research in general is a form of qualitative research that is often used to explore, describe, and explain a particular phenomenon using a variety of data sources (Baxter and Jack, 2008). Yin (2003) affirms that a case study is often used to create a model, develop a theory or suggest propositions. Accordingly, the answer to the research question should entail one of these end results: a model, a theory or propositions.

It is worth mentioning that using a case study approach to answer the first question occurred only after considering the four main conditions necessary for using case studies, which are:

1. The focus of the case study is to answer why and/or how questions

2. The study cannot change and/or manipulate the behavior of his participants or research community

3. The study believes that the phenomenon he is studying is relevant and reasonable to be explored, and

4. The association between the phenomenon and its context is not clear.

Consequently, the study started by determining his unit of analysis (nurses) and then limited this unit (nurses) by time (the focus is on the period after 2011), place (the focus is on Kasr El Eini hospital, which is the largest public hospital in Egypt) in addition to activity (how nurses perceive diversity).

Another important point that should be mentioned is that the author focused on understanding a single unique setting or environment and kept himself apart from analyzing within and across settings. That is why the author employed a holistic single case study not a multiple case study in answering his research question. Despite the emergence of methods like direct observation, focus groups, documentary analysis, participant observation and archival records used to collect data in this kind of research, the author relied primarily on face-to-face semi-structured interviews as the primary source of data and some public records, newspapers and social media as secondary sources of data.

Upon defining the research setting, the next task was to formally contact an administrator at the hospital to explore how to conduct the interviews. After a week of trials, the author of this article was able to contact one of the executive managers, and the author explained to him the plan of his research.

However, and after a couple of days, the manager apologized to the author saying that the time is not proper for such research because of the sensitive nature of the topic that touches upon one of the most dangerous problems in Egypt, and that it was better to postpone it for a while.

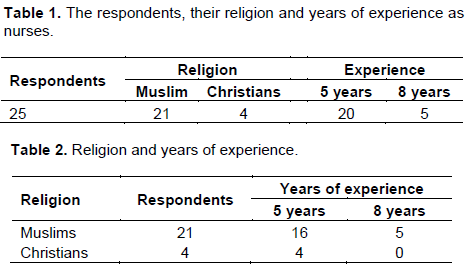

Upon finding a friend of a friend who supervises nurses at the same hospital, the author was able to approach 25 members of the nursing staff who agreed to voluntarily take part in the study. Tables 1 and 2 provided more details about the respondents.

It is worth mentioning again that the study did not manage to choose any one of his respondents, but he was satisfied with the number of respondents found and with their level of experience. The supervisor of these nurses affirmed that all the respondents (25 nurses) serve patients who are anti-regime (people arrested for political reasons, mostly affiliated with the Muslim brotherhood).

The study relied mainly on conducting semi-structured interviews that allowed a more thorough investigation of the respondents’ answers. The interviews were held from January to February 2016, and lasted an average of 40 min each. Although the author had planned to obtain supplementary information from hospital documents, unfortunately, the respondents all refused to provide any further documents to the author. Moreover, the interviews focused on a number of questions such as:

1. How do you define cultural diversity? What is your understanding of the hospital’s cultural diversity?

2. Do your age / religion/ gender affect the context you perceive? If yes, could you explain?

3. Does the hospital offer you discrete training about tolerance and inclusion? What is your evaluation of your colleagues’ assessment and promotion?

As a way of building trust and establishing a rapport, most interviews were conducted at Kasr El Eini hospital (place of work). The first 5 to 10 min of the interviews were used to break the ice between the author and his respondents, and the author elaborated his background for his interviewees, as well as the aims of this study, the reasons for conducting these interviews, and also the author thank his respondents for their voluntary participation. The author tried to take notes as much as possible during the interviews. Moreover, he reviewed the notes at the end of each day on which the interviews were conducted.

It was observed that during the interviews, the participants were reluctant to uncover some critical details with regards to the hospital out of fear of giving a negative impression that may compromise their standing with the hospital and in turn their appraisal and career. Some even went as far as refusing to have their interviews recorded when they were informed that the author would record them.

Moreover, because of the novelty of the procedure for some and because of their overloaded schedules, many participants asked that the interview questions be answered via phone instead of face to face. Added to this, the interviewees instructed the researcher to conduct all interviews in Arabic.

After conducting the interviews, detailed transcripts were made in which the contents of the interviews were typed out. Needless to say that the most interesting findings and information derived from the transcripts were coded. Owing to the specific focus of this research, questions and answers of the research were related to one of these concepts; namely, cultural diversity, discrimination, justice and etc.

Three criteria of trustworthiness were used to investigate the quality of the research: reliability, internal validity and external validity. According to Lillis (2006) and Ihantola and Kihn (2011), reliability is concerned with consistency or the extent to which the researcher accurately defines and represents the problem of his research. In this paper reliability was enhanced by audio recording some of the conducted interviews. Moreover, the author tried as much as possible to carefully select participants and accurately formulated his interview questions

External validity ensures that the results yielded may be generalized to other settings and time periods (Ryan et al., 2002). To improve external validity, the author of this study chose an adequate sample size and paid attention to transferability – which means that the results yielded can be extended to a wider context. To maintain internal validity or the “credibility of case study evidence and the conclusions drawn” (Ryan et al., 2002), this study did not start writing before gathering sufficient knowledge about diversity, the topic of this study. Internal validity was enhanced by cyclical proceedings of data collection and analysis. Upon the nurses’ desires, the interviews were conducted in Arabic, the native language of the researcher.

Given what has been articulated by Onwuegbuzie et al. (2011) who used the term legitimation instead of “validity” to describe the interactive process occurring at each stage in both quantitative and qualitative research, the study adopted inside-outside when doing his study. In inside-outside legitimation, respondents are encouraged to express their internal feelings/views and the researcher did his best to accurately observe the whole set of research components (Onwuebuzie and Johnson, 2011).

HOW NURSES PERCEIVE THEIR DIVERSITY WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF KASR EL EINI HOSPITAL (EGYPT)

Although the author of this article firstly intended to address the topic of diversity management at Kasr El Eini hospital, he changed his mind after conducting his first interview with his first respondent as he felt completely uncertain about what diversity means for respondents. Frankly speaking, the author discovered that the concept of diversity is very new in the context he had chosen to conduct his study in and consequently the majority of respondents were not fully aware of what diversity is, what values diversity includes, and what practices diversity involves. However, and upon elaborating the scope of diversity to every one of the interviewees, it was easy for the interviewer to realize that every one of the respondents was eager to talk freely.

It seems clear for the author that Kasr El- Eini hospital represents a small picture of the Egyptian society nowadays as the same state of societal division was observed in the radar screen. The third respondent said “they discriminate against me simply because I am a Christian woman”, the thought that was completely supported by the discourse of respondent number 17 who clarified that the majority of patients prefer to be served by Christian nurses because only Christian nurses fully understand their job duties not only because nursing is considered a human humble act but also because responsible job performance reflects a good image of religious belief.

Schaafsma (2008) and Siebers (2009b) indicate that people use similarities and dissimilarities to categorize themselves into groups, and as such they positively evaluate people who are similar and negatively evaluate those who are different. This provides interpretation for why Christian nurses only believe in other Christian colleagues.

In the same line Hornsey and Hogg (2000) clarify that individuals offer positive stereotype and favoritism for other in-group members while they have discrimination against those who are out-group members, the matter that clarifies a lot why Christian nurses implicitly accuse Muslim ones of being careless when doing their jobs.

Furthermore, Hogg and Abrams (1993) justify such identification with a particular group as a trial to curb subjective uncertainty and a step to gain further recognition and much more self-esteem. In line with Abrams (1993), Christian nurses think that no one should ask them about their claimed high performance level because the only answer Christian interviewees have here is that they do their best because they are Christian.

Interestingly, all respondents who belong to Christianity confirmed the difficulty they face in perceiving fair assessment and promotion opportunities. However; the interviewer directly questioned his respondents about the reasons of the previously claimed difficulty and the four Christian respondents affirmed that gender, religion and age are the main reasons for such difficulty, but noticeably, all of them didn’t consider work performance as a determinant of their assessment and promotion opportunities.

What seems a challenge here is that respondents don’t have any doubts concerning the process upon which assessment and promotions rely but instead their doubts are directed towards the fairness of the outcomes (pay, promotion, assessment, and etc.) they receive. This may reflect a huge deficit in adopting distributive justice standards at Kasr El Eini hospital. Rousseau et al. (2009) highlight that employees consider their organization to be fair only when the outcomes they receive like pay, assessment and promotion match contribution (for example, education, experience, effort and etc.) they invest in their workplace, and this is what management scholars call “distributive justice”.

Another important contribution that should be mentioned is what had been raised by two of respondents when claiming that their manager, who is a man, only smiles to their Christian colleagues. Furthermore, they added that only Christian weekly, if not daily, report formal complaints concerning discrimination against them at their hospital. They added that they experience a kind of discrimination, which is not real but they know how to use it to put managers, physicians and media under stress. Such expression of thoughts clearly reflects the state of division nurses live in as both Muslims and Christians no longer trust each other.

Accordingly, a question about inclusion should be raised here. Shore et al. (2011) assure that only through inclusion, despite dissimilarities employees accept each other as members in a same group and accordingly loyalty and trustworthiness are enhanced among them. Admittedly, each one of the nurses at Kasr el Eini hospital believes that she is perceived as an esteemed member of the hospital by belonging to a specific group, and hence out-group members are viewed as unsafe and undesirable to deal with.

A point that deserves to be highlighted is that all respondents asserted that they are treated like second-class citizens in their workplace because of the complete domination of men who occupy the full list of leading positions at Kasr El Eini hospital. That’s why two respondents indicated that living in a male-dominated society constantly hinders women’s fair assessment and development. Accordingly and based on the respondents’ view, there is a kind of preferential selection when selecting executives at the hospital.

Brown et al. (2000) highlights that granting any member and/or group a preferential advantage because of a specific biological or social status not only violates the principles of justice but also alleviates the values of merits, credentials, education, work experience and transparent codes of conduct employees expect to find at their workplaces, the aspect that negatively reflects on employee’s performance.

This study aimed to answer one question concerning how nurses perceive their diversity. Having conducted 25 interviews, the author of this paper succeeded in deriving an answer to the research question. The findings reflected a state of division the nurses at Kasr El Eini hospital are struggling with.

Unfortunately, according to social identity theory, Christian nurses strongly try to identify themselves with other Christian colleagues and show pleasure in announcing belongingness to their religious group. They collectively evaluate Muslim nurses negatively. The same can be said about Muslim nurses who accuse Christians of manipulating the situation of being a minority in the workplace and pressure managers to gain the best possible outcomes for themselves.

A high level of uncertainty was evident with regard to the value of inclusion at Kasr El Eini hospital. The analysis proved that Christians who are the minority are not treated as insiders nor are they motivated to retain their uniqueness at the hospital as they claim. Furthermore, Muslim nurses believe that interactions move smoothly only with other Muslim colleagues simply because, according to them, they are safe and similar. Therefore, such an absence of inclusion contributes considerably to the phenomenon of positive/negative stereotyping, prejudice, and bias towards in and out group members at Kasr El Eini.

A lot can be said about the role justice plays in enhancing employee loyalty, commitment, level of satisfaction, positive attitudes towards work, and hence definitely also performance (Siebers, 2009a). The case investigated here touches upon a claim that a mismatch exists between the nurses’ credentials (education, experience, effort and so on) on the one hand, and their assessment outcomes on the other (pay, promotion, assessment and so on). This is known academically as a violence of distributive justice, and negatively reflects nurses’ attitudes towards their job, colleagues and hospital as clarified in the study by Rousseau et al. (2009).

The main theoretical contribution made by this study lies in creating a model for diversity boundaries in the Egyptian context. This model clearly suggests that in and out-group differentiation, feelings of inclusion and exclusion and distributive justice are the main boundaries to attaining an inclusive diversity climate. Accordingly, the effective management of the three previously mentioned boundaries not only promotes the feeling of inclusion but also alleviates the use of the word “otherness” inside the work setting. Consequently, both similarities and dissimilarities are discovered and respected and all organizational members contribute to building a harmonized workplace (Figure 1).

Although many countries are experiencing a very similar state of division, and that diversity is considered one of the main features of life, the present results cannot be generalized to other similar contexts whether in a developed or developing country without first answering the same research question there. The main reason behind this is the huge cultural, societal, economic and political differences between countries.

IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGERS

Managers at Kasr El Eini hospital and top executives at the Egyptian ministry of health should worry about such discrimination and in-out group differentiation in the context of the hospital studied. Moreover, the following are the main implications that need to be addressed to eliminate cultural diversity bias:

1. A development of professional identity for the hospital should be fostered. This identity should be narrowed inside the hospital to department identities and also section identities. The main aim of developing this identity is to curb in-out group comparisons by using the concept of “good colleague” and subsequently, this identity will provide a common platform for collaboration, discussion and achievement.

2. The time is not proper for adopting any affirmative action or preferential selection because Muslims and Christians equally complain about bias and dis-crimination. Instead, an adoption of equal employment opportunity paradigm based on individual credentials (for example, education, experience, effort, etc.) should be considered. Needless to say that adopting such equal employment opportunity provides more space for hiring qualified people, eliminating nepotism and curbing ostracism.

3. Neutral communication should be extensively employed. It is important to communicate with nurses about their job descriptions and responsibilities in order to encourage an open door policy of communication that would allow diversity, create confidentiality, and motivate supervisors to intervene in any work-related bias and/ or prejudice. Therefore, this study may be considered as a prompt to create a clear anti-discrimination policy, with procedures and follow ups.

Some limitations of this study need to be brought to attention. Due to time constraints, it was not possible to conduct more than 25 interviews. Given the fact that the answer for the main question of the research is completely based on interviews, it appears, to some degree, that some of the interviewees answer the researcher’s questions in a socially desirable way, and it was not possible for the researcher to adjust their willingness to talk.

The researcher considers that his inability to choose all his respondents may have been the main reason for such behavior. Moreover, not everything said was used in the researcher’s analysis and also, not every interview was recorded. Some of the interviewees refused to have their interviews recorded. However, the researcher thinks that he got sufficient data to answer the main question of his research.

For future research, the researcher considers addressing the same research question to nurses in other departments and for other categories of employees (physicians and managers) at the same hospital. More-over, with such cultural differences problems organizations are urged to consider diversity management as a main part of any human resources development activity, whether this is the case at Kasr El Eini hospital is a matter that the researcher should find a clear answer for.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Agocs C, Burr C (1996). Employment equity, affirmative action and managing diversity: assessing the differences. Int. J. Manpower 17(4/5):30-45.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Alas R, Mousa M (2016). Cultural diversity and business hospital' curricula: a case from Egypt. Probl. Persp. Manage. 14(2):130-136.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ashikali T, Groeneveld S (2015). Diversity management for all? An empirical analysis of diversity management outcomes across groups. Pers. Rev. 44(5):775-780.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Barrett DJ (2002). Change Communication: Using Strategic Employee Communication to Facilitate Major Change. Corp. Commun. 7(4):219-231.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Baxter P, Jack S (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Report 13(4):544-559.

|

|

|

|

Breakwell GM (1993). Social representations and social identity. Papers Soc. Rep. 2(3):198-217.

|

|

|

|

Brown R, Charnsangavej T, Kenough KA, Newan ML, Rentfrow P (2000). Putting the affirm into affirmative action: preferential selection and academic performance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79(5):736-747.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Caiazza R, Volpe T (2015). Interaction despite of diversity: is it possible. J. Manage.Dev. 34(6):743-750.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-10-2013-0131

|

|

|

|

Cox T (1993). Cultural diversity in organizations: theory, research and practice. San Francisco: Berrettkoehler.

|

|

|

|

Cox T Jr. (1991). "The multicultural organization", The executive 5(2):34-47.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Cropanzano R, Mitchell M (2005). Social exchange theory: an interdisplinary review. J. Manage. 31(6):874-900.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Davis P (2005). Enhancing multicultural harmony: ten actions for managers. Nursing management 26(7):32,32D-32F, 32H

|

|

|

|

Devine F, Baum T, Hearns N, Devine A (2007). Managing cultural diversity: opportunities and challenges for Northern Ireland hoteliers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 19(2):120-132.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dogra N (2001). The development and evaluation of a programme to teach cultural diversity to medical undergraduate students. Med. Educ. 35:232-241.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Fao UG, Fao EB (1974). Societal structure of the minds. Springfield, IL: Charles Thomas.

|

|

|

|

Hassi A, Foutouh N, Ramid S (2015). Employee perception of diversity in Morocco: Empirical insights. J. Global Resp. 6(1):4-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Heuberger B, Gerber D, Anderson R (2010). Strength through Cultural Diversity: Developing and Teaching a Diversity Course. Coll. Teach. 47(3):107-113.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ (2005). Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. McGraw Hill.

|

|

|

|

Hogg MA, Abrams D (1993). Towards a single- process uncertainty- reduction model of social motivation in groups. In: M. A. Hogg & D. Abrams (Eds.), Group motivation: social psychological perspectives. Hemel Hempstead, England: Harvester Wheatsheaf. pp. 173-190

|

|

|

|

Hornsey M, Hogg, MA (2000). Assimilation and diversity: an integrative model of subgroup relations, Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 4(2):143-156.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hubbard EE (2011). The diversity scorecard: evaluating the impact of diversity on organizational performance (improving human performance), Burlington, VT: Butterworth- Heinemann.

|

|

|

|

Humphrey N, Bartolo P, Ale P, Calleja C, Hofsaess T, Janikofa V, Lous M, Vilkiene V, Westo G (2006). Understanding and Responding to diversity in the primary classroom: an international study. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 29(3):305-313.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ihantola EM, Kihn LA (2011). Threats to validity and reliability in mixed methods accounting research. Qual. Res. Account. Manage. 8(1):39-58.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Information about Kasr El Eini hospital.

View

|

|

|

|

Information about the physicians in Kasr El Eini.

View

|

|

|

|

Jain H (1998). Efficiency and equity in employment- equity/ affirmative action program in Canada, USA, UK, South Africa, Malaysia and India in developing competitiveness and social justice. 11th world congress proceedings, Bologne.

|

|

|

|

Johnston W, Packer A (1987). Workforce 2000: work and workers in the 21st century, Hudson Institute, Indiana Polis, IN.

|

|

|

|

King E, Gulick L, Avery D (2010). The divide between diversity training and diversity education: integrating best practices. J. Manage. Educ. 34(6):891-906.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kundu SC (2001). Managing Cross- Cultural Diversity: A challenge for present and future organizations. Delhi Bus. Rev. 2(2):1-8.

|

|

|

|

Lillis A (2006). Reliability and validity in field study research in Hoque, Z, (Ed.), Methodological issues in accounting research: theory and methods. Piramus, London. pp. 461-475.

|

|

|

|

Loden M, Rosener JB (1991). Workforce America! Managing employee diversity as a vital resource. Illinois: Business one Irwin.

|

|

|

|

Mazur B, Bialostocka P (2010). Cultural diversity in organizational theory and practice. J. Intercult. Manage. 2 (2):5-15.

|

|

|

|

Morrison M, Lumby J, Sood K (2006). Diversity and diversity management: Messages from recent research. Educ. Manage. Adm. Lead. 34(3):227-295.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mousa M, Abdelgaffar H (2017). A float in uncertainty and cynicism: an experience from Egypt. J. Commerce Manage. Thought 8:3.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mousa M, Alas R (2016a). Organizational culture and workplace spirituality. Arab. J. Bus. Manage. Rev. 6(3):1-7.

|

|

|

|

Mousa M, Alas R (2016b). Uncertainty and teachers' organizational commitment in Egyptian Public Schools. Eur. J. Bus. Manage. 8(20):38-47.

|

|

|

|

Mousa M, Alas R (2016c). Cultural diversity and organizational commitment: A study on Teachers of primary public schools in Menoufia (Egypt). Int. Bus. Res. 9 (7):154-173.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Nishii L (2013). The benefits of climate for inclusion for gender diverse groups, Acad. Manage. J. 56(6):1754-1774.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

O'Reilly CA III, Williams KY, Barsade W (1998). Group demography and innovation: Does diversity help? In: Neale, M.A., Mannix, E.A. and Gruenfeld D. (ed.), Research on managing groups and teams. Stamford, CT: JAI Press Inc.1:183-207.

|

|

|

|

Onwuebuzie AJ, Johnson RB (2006). The validity issue in mixed research. Res. Schools 13(1):48-63.

|

|

|

|

Onwuegbuzie AJ, Johnson RB, Collins KMT (2011). Assessing legitimation in mixed research: a new framework. Qual Quant. 45:1253-1271.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Pless N, Maak T (2004). Building an inclusive diversity culture: principles, processes and practice. J. Bus. Ethics 54(2):129-147.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Rijamampianina R, Carmicheal T (2005). A pragmatic and holistic approach to managing diversity. Problems Perspect. Manage. 1: 109-117.

|

|

|

|

Rousseau V, Salek S, Aube C, Morin EM (2009). Distributive justice, procedural justice and psychological distress: the moderating effect of coworker support and work autonomy. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 14(3):305-317.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ryan B, Scapens RW, Theobald M (2002). Research Methods and Methodology in Finance & Accounting, 2nd edition. Thomson, London.

|

|

|

|

Schaafsma J (2008). Interethnic relations at work: examining ethnic minority and majority members' experiences in the Netherlands. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 32:453-465.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Shore LM, Randel AE, Chung BG, Dean MA, Ehrhart KH, Singh G (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: a review and model for future research. J. Manage. 37(4):1262-1289.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Siebers H (2009a). (Post) bureaucratic organizational practices and the production of racioethnic inequality at work. J. Manage. Organ. 15(1):62-81.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Siebers H (2009b). Struggle for recognition: The politics of racioethnic identity among Dutch national tax administrators. Scand. J. Manage. 25:73-84.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Singal M (2014). The business case for diversity management in the hospitality industry, Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 40:10-19.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Tajfel H (1978). Differentiation between social groups. London: Academic Press.

|

|

|

|

Tereza M, Fleury L (1999). The management of cultural diversity: lessons from Brazilian companies. Ind. Manage. Data Syst. 99(3):109-114.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Tsui A, Egan T, O'Reilly C (1992). Being different: relational demography and organizational attachment. Admin. Sci. Qtly. 37:549-579.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

UN Report (2007). Rural Women Face Problems Of Discrimination And Manifold Disadvantages. Third Committee. 11th & 12th Meetings (AM & PM).

View

|

|

|

|

Vuuren H, Westhuizen P, Walt V (2012). The management of diversity in hospital- A balancing Act. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 32, 155-162.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Wrench J (2005). Diversity management can be bad for you. Race Class 46(3):73-84.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Yin RK (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

|

|

|

|

Zanoni P, Janssens M, Benschop Y, Nkomo S (2009). Unpacking diversity, grasping inequality: rethinking difference through critical perspective. Organization 17(1):9-29.

Crossref

|