ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to identify the specific marketing activities that contribute most to the performance improvement of seed producer cooperatives (SPCs) in Ethiopia. Both quantitative and qualitative procedures were adopted to extract information from knowledgeable and experienced experts using structured questionnaires. Results indicate that clear differences exist between Ethiopian SPCs in their intensity and quality of execution of marketing activities, indicating that these activities are managed and controlled by SPCs themselves. However, the similarity in patterns of intensity and quality of execution of marketing activities shows that these effects cannot be disentangled in the Ethiopian SPCs context. Ethiopian SPCs performed well on marketing activities related to interfunctional coordination, but poorly on activities associated with competitor orientation. SPCs are likely to perform better when they use a variety of marketing activities including quality control of product (seed), product differentiation, managing customer and supplier relationships, responding to customers and competitors, customer and competitor assessment, leadership, integration of activities, and interconnections among committees and members. Hence, to provide value to customers SPCs need to have resources and the capabilities to coordinate these resources in order to execute marketing activities efficiently and effectively.

Key words: Intensity of implementation, marketing activities, quality of implementation, seed producer cooperatives

The performance of any firm depends strongly on the specific activities that the firm implements (Forman and Hunt, 2005; Hansen and Wernerfelt, 1989; Tvorik and McGivern, 1997). Internal behaviours and the internal environment that influence the performance of firms are known as organizational business performance factors (Scott-Young and Samson, 2008; Wood, 2006). They can be altered and modified by the organization itself, such as adjustments to and adaptations in personnel capabilities, physical facilities, the organizational structure, and changes in budget allocations.

For firms it is important to identify the specific activities that affect their performance (Appiah-Adu et al., 2001; Scott-Young and Samson, 2008). This would help the firm to make appropriate decisions about investments and budget allocations. Marketing research has identified a wide variety of internal activities that influence firm performance (Mokhtar et al., 2009). There is, however, no comprehensive and unequivocal list of internal activities, as these may be contingent on the type of the business and the external environment (Appiah-Adu, 1998).

Marketing activities influence the success of the firm (Kumar et al., 2011). The purpose of marketing activities is to align organizational efforts with customer needs and thus to offer better products and services to customers. Empirical research reveals that there is a direct contribution of marketing activities to firm performance (Bansal et al., 2001). Thus, selecting appropriate marketing activities is crucial for increasing firm success. At the highest level of abstraction such marketing activities relate to the concept of market orientation and reflect customer orientation, competitor orientation, and interfunctional coordination (Kirca et al., 2005).

Dunn et al. (1986) have identified marketing activities related to product (planning, schedules, service), sales (control, forecasts, training, recruiting), control (inventory, quality), relations (customers, dealers, public), market research, pricing, advertising, warehousing, packaging, and credit extension. Firms need to identify the specific marketing activities that influence their performance, but this influence depends on the business strategy and the external context. As a result, different marketing activities have been identified in prior research as influential for firm performance. In the context of new product development success, for instance, Cooper and Kleinschmidt (1993) identified marketing activities such as market assessment (study), product and customer tests, and technical assessment. Marketing activities such as product promotion, product quality, employees’ training, pricing mechanisms, targeting strategy, and satisfied with skills levels were used to explain small firm overall business performance in the UK (Wood, 2006).

Whether and how firms implement marketing activities depends on the firms’ access to resources and their capabilities to coordinate those resources. Thus, both resources and firm capabilities influence firm performance (Nath et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2014). Firms use their own resources to implement marketing activities aimed at improving their competitive position in the market, which in turn enhances performance (Ketchen et al., 2007). Resources of a firm include both tangible (physical assets) and intangible (non-physical assets) resources. Firm capabilities refer to what the firm does at its core to effectively coordinate its resources. Firm capabilities enable the firm to coordinate, deploy and take advantage of its resources in the implementation of its strategies (Dutta et al., 2005). The firm’s capabilities may include the technological competences, skills and commitment of leadership, organizational capabilities, and strong cooperation and relationships with partners and stakeholders (Carmeli et al., 2010; Lin and Wu, 2012; Puni et al., 2014). Thus, identifying marketing activities that contribute to firm performance is the first important step for firms, but identifying resources and capabilities to implement those marketing activities effectively and efficiently is the second important step.

Prior research on identifying marketing activities and their effect on firm performance is scarce and has mostly focused on Investor-owned firms (IOFs) in developed economies (Morgan, 2012). Moreover, there has been little conceptual development and systematic examination of how researchers in marketing should measure the performance outcomes associated with marketing activities (Katsikeas et al., 2016). Based on the study examination of the literature, there has only been scant scholarly consideration regarding marketing activities in D&E economies in general and particularly for the small agricultural marketing cooperatives which are prevalent in such economies. With their dual objectives of serving customers as well as their members, cooperatives could benefit from insight into marketing activities that influence their performance, not only to gain more benefits from commercialisation, but also to support the well-being of their members (Grwambi et al., 2016).

To broaden our understanding of the influence of marketing activities on firm performance, this study focuses on the specific context of Ethiopian seed producer cooperatives (SPCs) and the marketing activities over which they have control. SPCs are business enterprises established by a group of farmers with the aim to produce and market quality seed to local markets and beyond, and to turn seed into a commercial product, so that it becomes a potential source of income and livelihood improvement for members (Subedi and Borman, 2013).

Previous studies in the context of SPCs in Ethiopia revealed that there is a positive and significant contribution of market orientation components to both the performance of the cooperative as well as to the livelihood improvement of its member farmers. SPCs that adopt a market orientation show better performance than SPCs that do not. Market orientation is a business philosophy which is operationalized through effective implementation of marketing activities reflected both by the intensity and quality of execution. Intensity of execution explicitly refers to the frequency with which SPCs practice marketing activities (‘do how often’), and quality of execution refers to the way in which SPCs implement marketing activities (‘do how well’). Therefore, this paper has two objectives: to understand which marketing activities improve most the performance of SPCs in Ethiopia; and to give practical and actionable advice for SPCs in terms of which capabilities are required to implement marketing activities that improve SPCs’ performance most.

Organization business performance factors

Organizational business performance factors by definition influence firm performance (Hansen and Wernerfelt, 1989; Wood, 2006), and are thus crucial to sustain a business (Appiah-Adu et al., 2001; Forman and Hunt, 2005). Organizational business performance factors comprise of factors within the firms (Scott-Young and Samson, 2008), which they can control and manage through their capabilities and business decisions. A wide variety of organizational business performance factors can influence firm performance (Wood, 2006). These include effective management (Rahman, 2001; Yusof and Aspinwall, 2000), human resource management (Jameson, 2000), strategy and firm experience (Ahmet, 1993; Liargovas and Skandalis, 2010), and marketing strategy development (Morgan et al., 2003). These organizational business performance factors are strengths if the firm performs them better and weaknesses if the firm performs them worse than competitors. Thus, managing these factors is key to continued success of the firm.

Identifying organizational business performance factors

Not all organizational business performance factors contribute equally to firm success, depending on the nature and objectives of the firm and its context. Organizational business performance factors that are considered critical for firm performance are known as critical success factors (CSFs) (Dadashzadeh, 1989). The concept of CSFs first appeared in the literature in the 1980s when there was interest in why some organizations seemed to be more successful than others, and research investigated the success components (Ingram et al., 2000).

Critical success factors are defined in different ways in the literature (Amberg et al., 2005). There are two broad views on CSFs. The first is to consider CSFs as necessary conditions for the survival of the firm. CSFs are “those things that must be done if a company is to be successful” (Freund, 1988). Saraph et al. (1989) viewed CSFs as those critical areas of managerial planning and action that must be practised in order to achieve effectiveness. Brotherton (2004) considers CSFs to be combinations of activities and processes that must be designed to achieve outcomes specified in the company’s objectives or goals.

Rockart (1979) explains CSFs as “the limited number of areas that, if they are satisfactory, ensure successful competitive performance for the organization.” The second view is to consider CSFs as conditions that significantly improve the performance of the firm. Pinto and Slevin (1987) defined CSFs as “factors, which, if addressed, significantly improve performance.” When those factors do not addressed properly, the performance of the organization will be less than defined. In both views, as the name implies, CSFs are a limited number of factors that significantly influence the performance of the firm (Selim, 2007). For the present study, from the perspective of SPCs in Ethiopia, CSFs are viewed as those activities and practices that improve the performance of the firm, which is in line with the second view. As identified in the literature CSFs are highly diverse, including among many: effective business strategies (Chen and Jermias, 2014), manpower and skills (Lin and Wu, 2012; Theodosiou et al., 2012), and leadership quality (Carmeli et al., 2010).

Business strategy can be described as a company’s behaviour in the market, including policies, plans and procedures (Gemunden and Heydebreck, 1995; Porter, 1980). It is generally assumed that a well-planned strategy helps in leading a firm to success (Lynch et al., 2000). This holds also for marketing strategy which plays a central role in winning and retaining customers, ensuring business growth and renewal, developing sustainable competitive advantages, and driving financial performance (Srivastava et al., 1998).

Manpower and skills enable firms to make use of their resources in pursuing managerial objectives (Droge et al., 1994). Leadership quality is expected to inspire, guide and energize employees, to set standards and mobilize people to make extraordinary things happen in firms, to overcome uncertainty, turn visions into realities and move organizations forward (Kouzes and Posner, 2012). Leadership quality facilitates organizing and integrating activities for firm performance (Campbell et al., 2009; Kouzes and Posner, 2012; Martin, 2007; Puni et al., 2014).

Most CSFs remain fairly constant over time, though they may change as the firm’s environment changes (Bullen and Rockart, 1981). CSFs may change over time depending on how the firm adapts to the external environment, including customers, competitors, suppliers, and regulators (Caralli, 2004). Thus, CSFs need to be reviewed periodically. For example, new legislation for the hotel industry on the privacy of customer information may result in a CSF like ‘customer information management’ for all businesses in this industry. CSFs could also differ from firm to firm, and from manager to manager (Caralli, 2004).

There are many levels of management in a typical organization, each of which may have vastly different operating environments. For example, executive-level managers may have CSF such as managing strategic relationships with business partners; and line-level managers may have CSF such as training employees (Caralli, 2004). Once a firm has identified its CSFs, it should properly maintain and manage those factors to compete successfully in a particular industry (Leidecker and Bruno, 1984).

Marketing activities and firm performance

Performance of firms is influenced by various marketing activities (Forman and Hunt, 2005). Marketing activities facilitate firms to exploit opportunities and satisfy customer needs. Marketing activities influence various performance measures such as customer acquisition, satisfaction, and retention, and financial performance (for example; revenue, profit) (Katsikeas et al., 2016; Kim and Ko, 2011).

Firms can recognize and exploit opportunities to more efficiently or effectively serve customer needs through the implementation of marketing activities (Webb et al., 2010). The competitive environment of modern day firms necessitates the successful implementation of marketing activities (Appiah-Adu et al., 2001). Through efficient implementation of marketing activities, firms respond effectively to changes in the needs of customers (Holcombe, 2003). Moreover, marketing activities build long-term assets of firms such as brand equity (Rust et al., 2004).

Literature has identified marketing activities that increase performance (Scott-Young and Samson, 2008). The importance of marketing activities depends on the objectives, the strategy and the implementation capabilities of the firm (Mokhtar et al., 2009). Those marketing activities that significantly contribute to firm performance should receive high priority (Kumar et al., 2011). Identifying marketing activities as CSFs is crucial for marketers to obtain budget for their implementation (Morgan, 2012).

Research in marketing has increasingly focused on building knowledge about how firms’ marketing activities contribute to performance outcomes. In the context of small firms in the US, Dunn et al. (1986) identified key marketing activities. These activities relate to product (planning, schedules, service), sales (general sales, control, forecast, training, recruiting), control (inventory, quality), relations (customers, dealers, public), market research, pricing, advertising, warehousing, packaging, and credit extension.

Siu (2002) explored to what extent internet-based and traditional small firms in Taiwan differ in the execution of these marketing activities (Dunn et al., 1986). He found that both internet-based and traditional small firms focus on sales, product planning, and customer relationships. However, traditional firms emphasize quality control, while their internet-based counterparts focus more on dealer relationships and sales forecasts. This demon-strates similarities and differences of marketing activities as CSFs across firm types.

Cooper and Kleinschmidt (1993) considered market assessment (study), product and customer tests, and technical assessment as CSFs for new product development success. Marketing activities such as targeting strategy, quality product, employees training, pricing mechanisms, and product promotion were used to explain small firms overall business performance in the UK (Wood, 2006).

Market orientation and marketing activities

Literature presents strong evidence for the positive contribution of market orientation to firm performance (Cano et al., 2004; Kirca et al., 2005). Market orientation provides a business with a better understanding of its customers, competitors, and environment, which subsequently leads to superior performance (Kirca et al., 2005). Market orientation urges employees to develop and exploit market information to create and maintain superior customer value (Narver and Slater, 1990).

In this study, we view market orientation as the extent to which culture is devoted to meeting customers’ needs and outperforming competitors (Narver and Slater, 1990). Market-oriented firms implement marketing activities to achieve their objectives (for example, satisfaction of their customers). Market orientation influences performance through effective implementation of marketing activities (Hult et al., 2005). Han et al. (1998) explained that market orientation remains incomplete if it is not understood through which activities a market-oriented culture is transformed into superior value for customers.

Market-oriented culture of a firm embodies values and beliefs that guide organizational activities that enhance performance (Langerak et al., 2004), and provides a unifying focus for the efforts and projects of individuals and departments within organizations (Baker and Sinkula, 1999). Market orientation culture motivates and inspires the implementation of various marketing activities, which eventually influences firm performance (Atuahene-Gima, 1996; Gatignon and Xuereb, 1997; Jorge et al., 2012; Langerak et al., 2004; Moorman, 1995).

The influential body of literature in the field of strategic management emphasizes the importance of firm resources and their implications for firm performance, which is a basis for the resource-based view (RBV). Firm resources include both tangible (physical) assets (for example; machines, buildings, labor) and non-tangible (non-physical) assets (for example; information, knowledge, reputation) (Teece et al., 1997). RBV deals with how a firm’s resources influence performance (Hult et al., 2005).

Firms need to access resources to implement marketing activities and increase positional advantage, which in turn enhances performance (Ketchen et al., 2007). RBV suggests that a firm has a foundation for a sustained competitive advantage if its resources provide value to customers, are superior to those of competitors, and are difficult to imitate or substitute (Barney, 1991). However, RBV is criticized as it lacks to explain how resources are developed and deployed to achieve competitive advantage, and it does not consider the impact of dynamic market environments (Lengnick-Hall and Wolff, 1999; Priem and Bulter, 2001).

To address these limitations, the dynamic capabilities view (DCV) is proposed (Newbert, 2007). Scholars of the DCV extend RBV to examine the influence of dynamic markets (Helfat and Peteraf, 2003). According to Teece et al. (1997), dynamic capability is defined as “the firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments.”

The DCV posits that since marketplaces are dynamic, what explains interfirm performance variance over time is the capabilities by which firms’ resources are acquired and deployed in ways that match the firm’s market environment (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Makadok, 2001). The dynamic capabilities of the firm should be better than its counterparts to perform well in the market place (Bingham et al., 2007).

Teece et al. (1997) describe that capabilities are dynamic when they enable the firm to implement new strategies to reflect changing market conditions by combining and transforming available resources in new and different ways. Based on RBV and DCV, our argument is that marketing activities require resources and capabilities if its value to the firm is to be fully realized (Dutta et al., 2005; Morgan et al., 2009).

Prior studies integrate RBV of the firm and the DC perspective with marketing theory (Bharadwaj et al., 1993). Not all firms are able to generate and sustain competitive advantage by implementing a market orientation (Day, 1994; Hunt and Morgan, 1995). Those market-oriented firms that enable the use of their resources effectively and efficiently could implement marketing activities, which eventually provide greater improvement for firm performance.

Market orientation, in isolation, is unlikely to qualify as dynamic capability; it needs to be complemented by other internal resources that will lift its competitive value (Menguc and Auh, 2006; Moorman and Slotegraaf, 1999). Market orientation encourages firms to use their capabilities to coordinate resources (for example, employees) in order to better serve customers (Hult et al., 2005). To perform marketing activities effectively and efficiently firms need resources and capabilities to coordinate those resources.

Literature reveals that market orientation inspires the execution of various marketing activities (Jorge et al., 2012) facilitated by the firm’s resources and capabilities (Menguc and Auh, 2006). The way how firms execute these marketing activities affects performance. This is governed by the level of intensity and quality of execution of the marketing activities. The intensity of execution refers to what degree the firms are practicing marketing activities (that is, frequency); whereas the quality of execution refers to the way in which firms are practicing marketing activities (that is, how good they do it). Higher execution of intensity and quality could lead to higher firm performance.

There is a positive association between market orientation components and performance in the Ethiopian SPCs context. The present study augments this work by identifying the specific marketing activities that drive firm performance. The performance of SPCs is influenced by the effective and efficient execution of marketing activities both in terms of intensity and quality. The effective execution of marketing activities requires resources and capabilities. Market orientation in the Ethiopian SPCs context comprises customer orientation, competitor orientation, interfunctional coordination, and supplier orientation. Performance includes customer satisfaction, financial performance, and members’ livelihood performance.

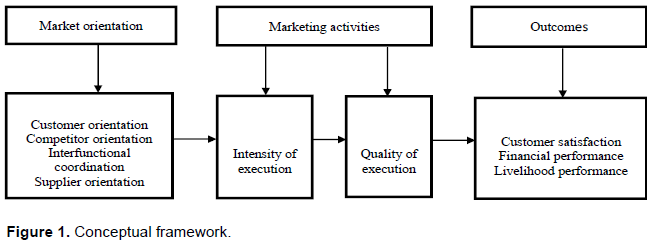

In Figure 1, we show a conceptual framework relating market orientation, and the intensity and quality of execution of marketing activities, to outcomes. The expectation of this relationship is that market orientation stimulates SPCs to execute key marketing activities (both in terms of intensity and quality), and the effective execution of these activities eventually influences performance.

Seed producer cooperatives categorization

Data were collected from 24 SPCs in Ethiopia. These SPCs were selected based on the assessment of the market orientation-performance relationship and profiled in terms of self-rated level of marketing orientation and performance. Based on these self-assessments, SPCs were priori classified into two distinct groups:

(1) High market orientation and high performance (11 SPCs) that is, high performing SPCs; and

(2) Low market orientation and low performance (13 SPCs) that is, low performing SPCs. Classification was based on the median scores for market orientation and overall performance.

Sample selection

Data were obtained from experts, selected on the basis of their experience with and knowledge of the marketing activities and performance of the 24 SPCs included in the study. We identified experts that are experienced with seed business in Ethiopia and have an in-depth understanding on the SPCs. Experts included three university instructors who have many years of teaching and research experience and participated in seed projects to support SPCs, 13 project officers (from seed business projects and NGOs) who are among the best experts in sustainable seed business development of SPCs in Ethiopia, and three experienced local experts closely working with SPCs. Of the 19 experts involved, sixteen hold an MSc degree and three a BSc degree in the field of agribusiness, cooperative marketing, economics or seed sciences.

Procedure

Experts were contacted in person and by telephone, and asked to participate in the research. Those that agreed were further briefed about the objective of the research, the reason why they were selected to participate in the study, and reassured about the anonymity of their responses. Then, the questionnaires were handed over to the experts either during face-to-face contact or via mail. To ensure timely completion, help and reminders were given via regular telephone communication. Experts were identified from different organizations that are working with SPCs. Experts evaluated a specific SPC only when they were familiar with its marketing activities and performance. As a result each SPC was evaluated by one to four experts, and mostly by two experts. A total of 52 questionnaires across the 24 SPCs was obtained.

Measures

Marketing activities

Specific marketing activities were identified that relate to the market orientation of SPCs. Prior research reported that supplier orientation next to customer orientation, competitor orientation, and interfunctional coordination are defining factors of market orientation practices among Ethiopian SPCs.

Initially, a gross list of marketing activities was identified based on literature review and SPCs’ experience. Marketing activities that were identified from literature ranged from activities limited to the specific firm (that is, in-house product testing) to activities that are broadly applicable to most firms (that is, quality control).

Further, a number of specific marketing activities were considered that the Ethiopian SPCs are practicing based on the previous study. Experienced experts were consulted to comment on the proposed list of marketing activities taken from the literature and local practices. A series of consultations with experts helped to identify and remove those marketing activities that could not sufficiently represent the SPCs context (for example, market research) and that were found redundant and having similar meaning.

As a result, the process identified 15 marketing activities potentially related to performance of the SPCs in Ethiopia, and these were categorized under the four components of market orientation. Customer orientation included five marketing activities, namely

(1) Quality control of product (seed)

(2) Collection of information on customer needs

(3) Assessment (verification) of customers’ satisfaction

(4) Responsiveness to customer needs and complaints (volume, diversification), and

(5) Direct customer visits to maintain customer relations.

Competitor orientation comprised three marketing activities, namely

(1) Differentiation of product from competitors

(2) Collection of information on competitors’ activities, and

(3) Responsiveness to competitive actions (pricing).

Interfunctional coordination included five marketing activities, namely

(1) Their leaders motivating committees and members

(2) Committees’ communication and integration

(3) Sharing of information within the cooperative

(4) Their leaders integrating activities, and

(5) Inter-committee discussion on market trends and developments.

Supplier orientation involved two marketing activities, namely

(1) Meeting with suppliers for opportunities (approach suppliers), and

(2) Maintaining relationships with suppliers (supplier relations).

For all, 15 marketing activities experts rated the intensity and quality of execution. Intensity of execution of marketing activities was defined as the frequency with which an SPC practices the marketing activity and was rated on a five-point Likert scale with scale points rated as never, seldom, sometimes, often and constantly. Quality of execution of marketing activities was defined as the way in which an SPC implements the marketing activity, measured on a five-point Likert scale with scale points rated as poor, fair, satisfactory, good and excellent.

After rating the marketing activities on their intensity and quality of execution, experts were asked in open response format to elaborate on their ratings by explaining the current practices of the specific SPCs. Experts described the behaviours of the SPCs for each of the marketing activities. Moreover, they were asked to suggest areas of improvement that the SPCs should consider in order to improve their performance. The qualitative data were aggregated into the four components of market orientation.

Performance

Expert ratings of SPC performance were collected to validate the a priori classification on self-rated performance. Performance was measured on 11 performance indicators categorized under three dimensions based on previous research: customer satisfaction, financial performance, and members’ livelihood performance.

The first two performance measures were adapted from the marketing literature and the latter performance measure was based on the current practices of Ethiopian SPCs. Financial performance and customer satisfaction are the two most prominent business performance measures in marketing studies (Boohene et al., 2012; Hilal and Mubarak, 2014).

Livelihood performance is associated with cooperative business objectives in the D&E economies. Customer satisfaction was measured with four indicators:

(1) Customers getting (acquiring) the quality seed they want

(2) Receiving positive feedback from customers

(3) Customers’ intention to buy the seed from the firm, and

(4) Customers repeat purchasing the seed.

Financial performance included four indicators, namely

(1) The firm increasing its assets

(2) The firm increasing its market share

(3) The firm shows progress in capital improvement, and

(4) The firm increasing its net profit.

Members’ livelihood performance was measured with three indicators, namely

(1) Members’ family having sufficient food throughout the year

(2) Improvement in the quality of members’ house, and

(3) Members having basic (necessary) household equipment.

The performance measures were assessed on a five-point Likert scale with scale points rated as strongly disagree, disagree, neutral/uncertain, agree and strongly agree.

Data analysis

Quantitative and qualitative procedures were employed in data analysis. Repeated measures analysis of variance was used to assess the association between the intensity and quality of execution of the marketing activities among high and low performing SPCs. Analysis of variance was also used to assess the difference between high and low performing groups for implementation of marketing activities. Comparisons between the high and low performing groups were based on two sample t-tests. Expert-based performance measures for the two groups were similarly compared between the two groups by means of two sample t-test. To complement the quantitative analysis, qualitative experts’ judgements (elaborations and suggestions) were summarized and aggregated on the basis of the four components of market orientation. We assessed the similarities and differences of the two groups in the execution of the marketing activities, and specific recommendations of the experts. Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software was used for data analyses.

Comparison of intensity and quality execution of marketing activities

As each expert provided multiple ratings, the associations between the intensity and quality of execution of marketing activities both for high and low performing SPCs were assessed using repeated measures ANOVA based on the averaged data per SPC.

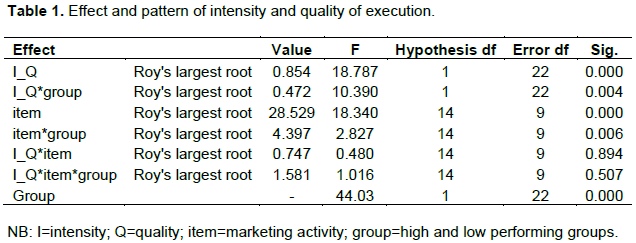

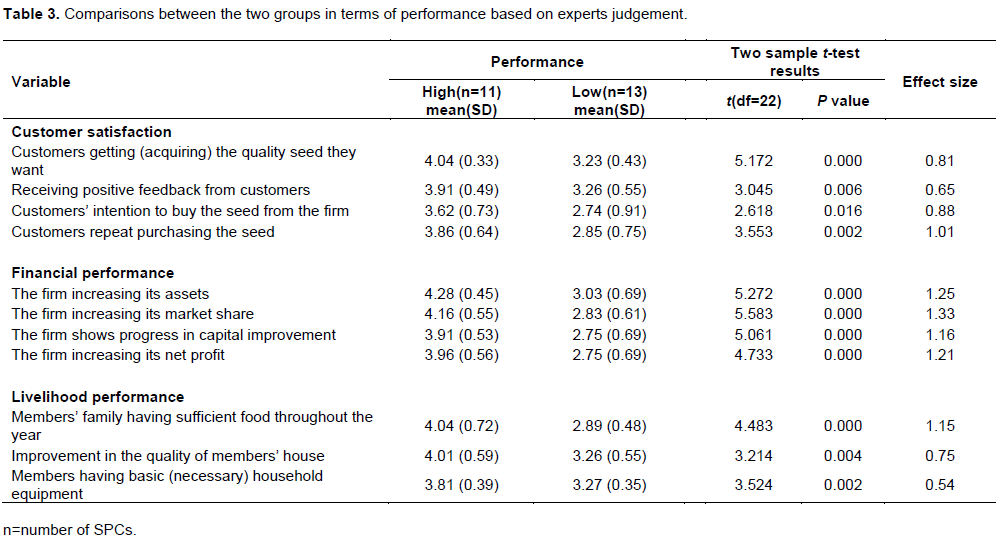

Results (reported in Table 1) show the main and interaction effects for intensity versus quality ratings (I_Q), the different marketing activities (item), and the high versus low performing groups of SPCs (group). The scores for intensity and quality of execution in the Ethiopian SPCs are significantly different overall (F=18.787; p<0.000) reflecting the different response scales for intensity and quality.

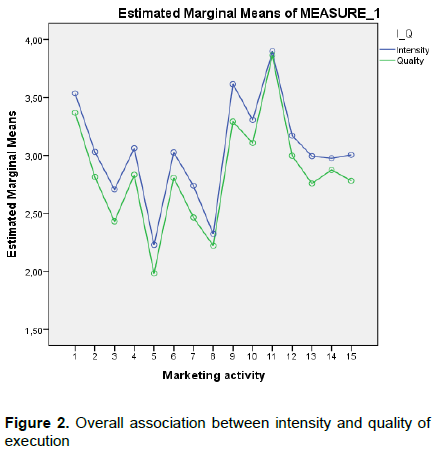

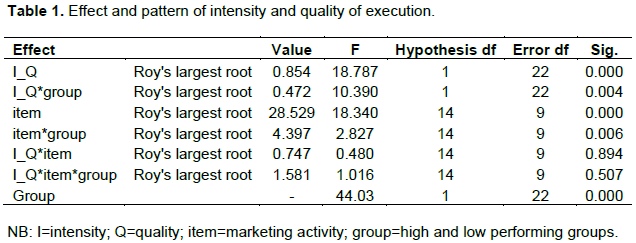

The scores of intensity and quality of execution also significantly differ between the high and low performing SPCs (F=10.39; p=0.004) showing that the difference between intensity and quality is not equal between the two groups. The scores between marketing activities are significantly different (F=18.34; p<0.000; Figure 2) indicating that the influence of various marketing activities differs. The differences among marketing activities are also significantly different between the high and low performing SPCs (F=2.827; p=0.006). However, the results also show that the patterns of intensity versus quality of execution ratings do not differ across the marketing activities (F=0.480; p=0.894) and that these do not differ between the high and low performing groups of SPCs (F=1.016; p=0.507).

Together these results show that ratings of quality of execution do not provide unique information compared to those on intensity of execution (and vice versa). This may indicate that intensity of practice increased goes hand in hand with quality of execution. Hence, we further only discuss the intensity of execution of marketing activities between high and low performing groups of SPCs. Results also illustrate the significant differences between the two groups (F=44.03; p<0.000) regarding the implementation of the marketing activities.

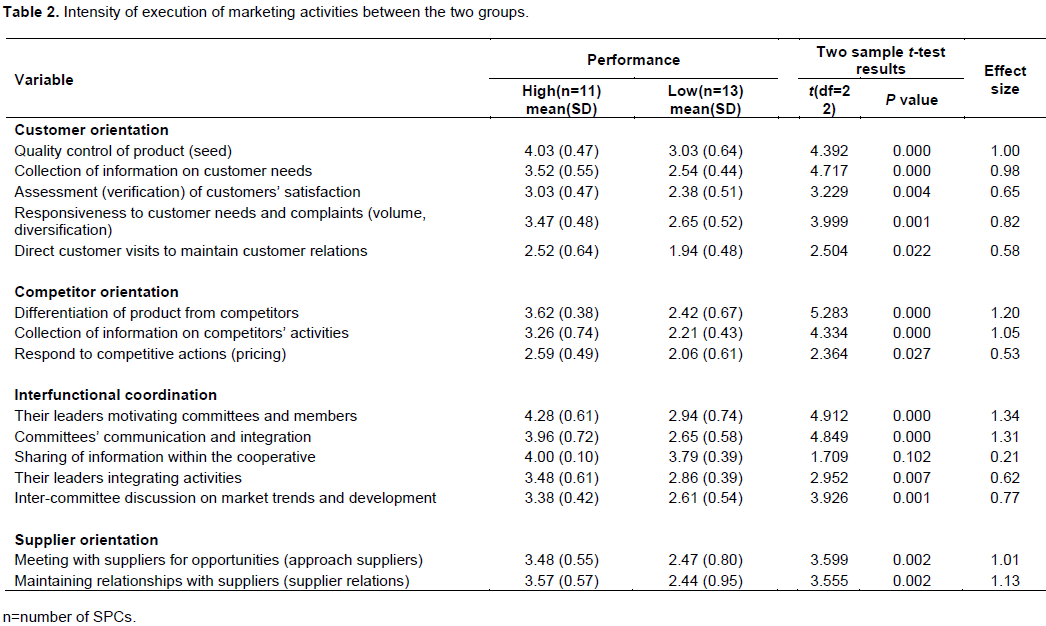

Intensity of execution of marketing activities

Table 2 compares the similarities and differences between high and low performing SPCs in terms of the intensity with which marketing activities are executed. The results show that, for almost all marketing activities, high performing SPCs outperform low performing SPCs in terms of intensity with which these marketing activities are being implemented.

However, from the mean ratings (5 point scale) it is evident that some of the key marketing activities are more common than others.

For customer orientation, high performing SPCs conduct quality control to improve seed on a regular basis as well as collecting and responding to customer information. However, direct customer intimacy, through direct visits to customers is much less common. This indicates that Ethiopian SPCs have limited experience in direct customer visit regardless of their level of performance. Despite these varying levels of implementation intensity, all customer related marketing activities significantly differentiate high performing SPCs from their low(er) performing counterparts. Concerning competitor orientation, all competitor related marketing activities are significantly different between high and low performing SPCs. High performing SPCs make efforts to differentiate their products and collect competitor information.

However, responding to competitive actions (that is, pricing) is uncommon. Low performing SPCs generally show lower frequency of implementation in competitor related marketing activities than other marketing activities associated with customers, internal coordination and suppliers. All, except sharing information, interfunctional coordination related marketing activities significantly differentiate high performing SPCs from low performing SPCs. High performing SPCs often perform better in motivating members, interdepartmental communication, and integrating activities than low performing SPCs.

Social networks and strong cultural practices assure that both high and low performing SPCs are effective in sharing of information within the firm. In general Ethiopian SPCs show more marketing activities related to interfunctional coordination than marketing activities associated with customers, competitors and suppliers. Supplier related marketing activities significantly differentiate high performing SPCs from low performing SPCs. High performing SPCs often meet and approach suppliers and make an effort to maintain relationships with suppliers. Low performing SPCs seldom have contact with suppliers. This indicates better performing capacity (network, external contact) of high performing SPCs than low performing SPCs to access the necessary inputs particularly basic seed.

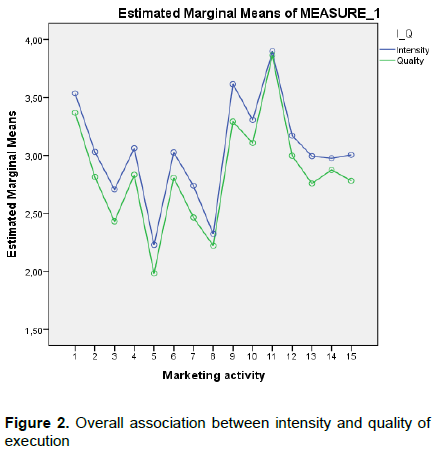

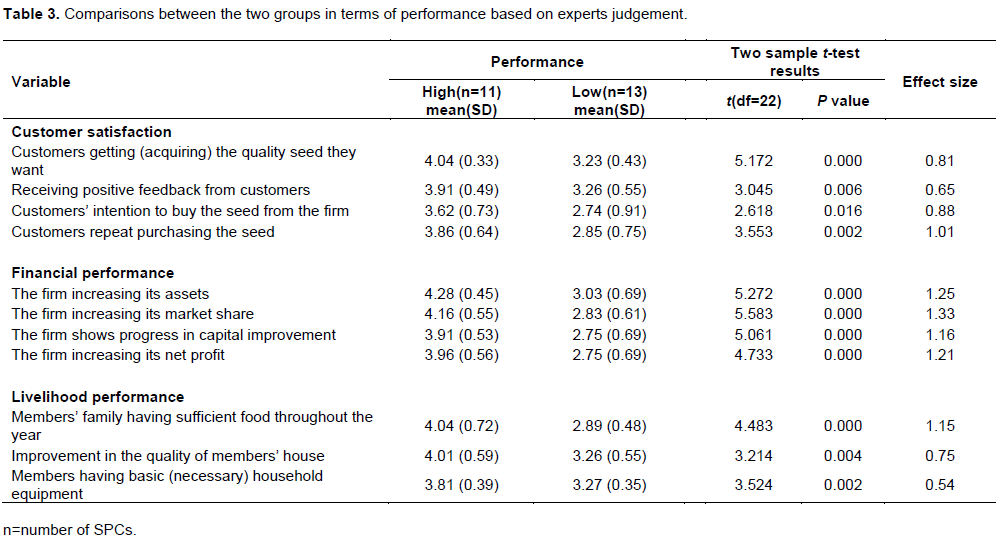

Experts’ judgement on SPCs’ performance

Table 3 shows that the expert judgments on performance by and large confirm the self-rated performance by the SPCs. Significant differences exist between the two groups for all performance measures (customer satisfaction, financial performance, and members’ livelihood improvement). The largest differences were observed for financial performance con-firming that high performing SPCs are better in financial capabilities than low performing SPCs. In particular, a big difference was observed between the two groups for increased market share (volume of seed sold), which indicates the better capabilities of high performing SPCs in supplying larger quantity of higher quality seed into the market than low performing SPCs. Low performing SPCs exhibit lower capital improvement and lower net profit gain than high performing SPCs. Considerable differences were also observed between the two groups for measures of customer satisfaction particularly for perceived quality seed. For the case of members’ livelihood improvement, the highest difference was observed for having sufficient food throughout the year. Both groups performed well in increasing their assets.

Further elaboration by experts

This section summarizes experts’ more detailed qualitative information on why and how high performing SPCs executed the marketing activities better and more frequently than low performing SPCs. In addition, we present experts’ specific suggestions on how SPCs might practice activities in order to improve their performance.

Customer orientation

In relation to customer orientation related marketing activities, experts emphasised that SPCs traditionally have quality control committees (or a sort of responsible body) in place for implementing quality control of product (seed). Compared to low performing SPCs, high performing SPCs are typically characterised by more capable and better experienced committees with clear tasks and responsibilities, and members with more technical skills. They also have strong internal bylaws to maintain the seed quality that their members must follow showing high performing SPCs have better capabilities of internal management.

Experts highlighted that high performing SPCs manage to get access to high quality basic seed from suppliers, implement better agricultural technologies and practices, and more often work with an external quality assurance agency. Also, whereas low performing SPCs tend to rely entirely on externals as a source of customer needs, high performance SPCs augment such knowledge through direct contacts with final buyers (customers) using formal and informal approaches. Experts described that high performing SPCs sometimes directly visit customers’ field to get feedback or acquire feedback via telephone. However, SPCs do not have sufficient experience to assess customers’ satisfaction in more formal ways.

Experts emphasize the importance of accurate information about the needs of prospective buyers (customers) before the start of seed production. Therefore, experts suggest all SPCs should visit their customers and use all the possible mechanisms (both formal and informal) to assess the level of their customers’ satisfaction. Experts advised for SPCs to visit their customer farmers field to receive direct feedback. In particular low performing SPCs should focus on the strengthening of their internal seed quality control mechanisms, closely working with external seed quality assurance agencies, and increase the seed production skills of their members through trainings.

Competitor orientation

Concerning competitor orientation related marketing activities, experts agreed that most SPCs commonly produce only a few types of crops or varieties (for example, bread wheat, tef). However, experts also mentioned that most high performing SPCs are capable in, and have better experience of, producing diversified crops and varieties and/or unique crops (for example, onion, haricot bean, hybrid maize, pulse crops etc.) than low performing SPCs.

According to experts, these unique crops have high local and international market demand. Experts also indicted that high performing SPCs produce seeds that require high skills and effective coordination, something that their lower performing competitors cannot achieve easily. A few of the high performing SPCs, according to experts, engage in seed value addition activities and fulfil the legal seed quality certification standards; but both high and low performing SPCs lack defined strategies to differentiate themselves from what competitors do.

Experts described that high performing SPCs are trying to access competitors’ information through secondary sources, but that most low performing SPCs do not bother about competition. In general Ethiopian SPCs accidentally gather information about competitors during various formal and informal events such as in workshops, local administrative meetings, field days, exhibitions, seed fairs, religious and local festivities. Experts mentioned price adjustment and large volume seed supply are some of the activities that high performing SPCs practice to respond for competitive actions. Experts agreed that Ethiopian SPCs do not perform as expected on competitor-oriented marketing activities compared to other activities related to customers, internal coordination and suppliers.

In this regard, experts highlight the consideration of competitor-related marketing activities if SPCs want to perform well in the market. Hence, the suggestions of experts for low performing SPCs are that they should include unique crop seed (for example, onion, haricot bean, hybrid maize, pulse crops etc.) in their production portfolios and train their members to have special skills to produce and maintain the seed quality according to the standards. They should also clearly know first their target competitors and design specific responsive mechanisms.

The specific mechanisms include price adjustment, seed value addition activities, and the production of crops that have high local demand and for which big companies

have low interest. Leaders of low performing SPCs should approach partner organizations to acquire knowledge to identify their competitors. In specific, Ethiopian SPCs should develop strategies to assess precise information about their competitors using various mechanisms executed by themselves and through partners in the network. They should also develop adaptation strategy to tackle the competitors’ actions.

Interfunctional coordination

For interfunctional coordination related marketing activities, experts underlined that the vast majority of leaders in high performing SPCs are capable of motivating members and committees through official recognition, awards and financial rewards (for example, money, farm tools, certificates).

According to experts’ elaboration, the capacities of leaders from high performing SPCs are associated with their higher level of commitment, dedication, experience, and skills than that of leaders from low performing SPCs. Low performing SPCs do not reward members and they have limited experience with informal ways to giving recognition. Leaders of high performing SPCs provide members access to inputs (basic seed), which is an effective motivator for members.

Experts mentioned that high performing SPCs usually do have more specialized committees with clear tasks and responsibilities than low performing SPCs indicating more specialization and a higher need of integrate the activities. High performing SPCs also assign specific tasks to appropriate committees and/or individual members, and constantly oversee those tasks.

Experts also described that in the majority of high performing SPCs, there are regular meetings among leaders (almost every two weeks), and among various committees (almost every month), which reflects the good communications between committees. They discuss various seed business issues including what they should produce, where and how to sell the seed, the volume and quality of seed, price mechanisms, customer handling and relationships, seed value additions, and access to basic seed from suppliers.

In low performing SPCs leaders meet irregularly, not frequently, and in some cases don’t meet for several months. Experts agreed that both groups of SPCs perform well in sharing information driven by strong cultural practice in the community. Experts highlighted that most high performing SPCs have well-developed plans (year and/or multiple year planning) which is absent in the majority of low performing SPCs.

According to experts’ suggestions, low performing SPCs should assign leaders that have commitment, dedication, experience, and skills to coordinate activities. Experts stressed that low performing SPCs should take lessons from high performing SPCs and implement specialised committees and guarantee connectedness between them, increase the frequency of committee meetings, and discuss critical market developments and trend. Rewards have social value in the rural community, so low performing SPCs should practice to acknowledge the efforts of leaders and their members through various reward mechanisms for better motivation. For high performing SPCs, experts suggested that they should recruit professional managers to minimize the leaders’ work load and cherish their commitment.

Supplier orientation

Regarding supplier orientation related marketing activities, experts described that high performing SPCs have direct and frequent contact with suppliers. However, in the low performing SPCs contact with suppliers is mostly limited to when they need basic seed during planting time. Experts underlined the efforts of high performing SPCs to request support from other stakeholders (research institutes, GOs and NGOs) to maintain their relationship with suppliers. They often approach and negotiate with suppliers to access inputs ahead of planting time.

Experts emphasised that high performing SPCs often work in contractual seed production and marketing arrangements with suppliers, other big seed enterprises and seed unions, which helps them to secure the basic seed and maintain the relationship. Experts described that high performing SPCs have good experience in working with research institutes and suppliers during seed (varieties) testing and demonstrations. In most cases, suppliers consider high performing SPCs as their strategic and loyal partners. Low performing SPCs are largely dependent on external support to access inputs (particularly basic seed) from suppliers.

In terms of suggestions, experts emphasised that all SPCs should review periodically their relationships with suppliers and plan actions when improvements are needed. In particular for low performing SPCs, experts recommended that they should approach suppliers not only to obtain seed, but focus also on long-term relationships, and meet frequently to develop good firm-supplier relationship. Moreover, they should signal their demand ahead of time and should avail themselves as strategic partners for suppliers in joint seed demonstration and production activities. For high performing SPCs, experts suggested that they should clearly consider supplier relations as part of their business strategy as suppliers can influence the quality, timeliness and competitiveness of their product. Since a few seed suppliers are found in Ethiopia, experts advised SPCs to be patient and keep their relationship with suppliers even sometimes suppliers are not able to keep their promise.

The study findings reveal that the performance of SPCs is influenced by effectively and efficiently implementing marketing activities identified as CSFs. High performing SPCs implemented marketing activities more and better than low performing SPCs, which suggests that these marketing activities are CSFs. These marketing activities can be managed by SPCs themselves. The finding shows that effective implementation of marketing activities remains a key strategy for SPCs to improve their performance.

In extant literature in marketing and strategic manage-ment (Morgan et al., 2009), it is suggested that market orientation inspires the implementation of marketing activities based on the resources that firms have and their capabilities to coordinate these resources effectively and efficiently. Our findings of a significant difference between high and low performing SPCs in implementation of these marketing activities is consistent with this view. Most high performing SPCs have strong leaders, members with better knowledge and skills, and have better external linkage with suppliers and other supporting organizations than low performing SPCs. These, in turn, help them to give special attention and devote their resources to the implementation of the key marketing activities.

The findings of this study show a strong association between intensity and quality of execution of marketing activities in the current Ethiopian SPCs context. More specifically, contrary to our expectation, the study does not support the significant difference between intensity and quality of execution for marketing activity in SPCs context. The patterns of intensity and quality of implementation of marketing activities are found to largely overlap. One possible explanation for absence of a significant difference between intensity and quality of execution is that intensity of execution ultimately results in quality of execution. In other words, for the current SPCs, we do not find unique contributions to performance of quality of execution over and above intensity of execution of marketing activities. It may be that the intensity of execution increases the quality of execution. In the current Ethiopian SPCs situation, the imple-mentation frequency of the marketing activities is considered as very important rather than quality of implementation.

As reported in the literature (Carmeli et al., 2010; Kouzes and Posner, 2012; Puni et al., 2014), the role of mangers (leaders) is indispensable for the implementation of marketing activities and thus to ensure firm performance. Our findings indicate that leadership quality of SPCs differentiates SPCs in effective implementation of marketing activities and consequently in performance. Empowered leadership is the base for the success of the business.

In the case of SPCs, the role of cooperative leaders is an important element that has a significant impact on business culture. The leader’s commitment, motivation, and experience determines the efficient way of integrating various firm resources and activities. Leaders’ motivation could attract members in and inspire members to committing themselves to the success of the business. The considerable variation among Ethiopian SPCs depends on the knowledge and experience of leaders, which can foster or inhibit the development of cooperative’s success (Subedi and Borman, 2013).

The role of leaders (top management) would help a firm to achieve its objectives (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993). The implementation of customer-focused marketing activities contributes to SPCs performance. The proper imple-mentation of marketing activities that related to customer orientation could help SPCs to create and maintain high value products for customers. SPCs that develop and strengthen their customer-focused marketing activities also increase their customers’ satisfaction, market share and profit (Chi and Gursoy, 2009).

As the firm can satisfy its customers, the willingness of customers to pay for the product increases which eventually improves the performance of the firm. This confirms the effect of customer-focused marketing activities on the various performance measures (Joung et al., 2015; Lings and Greenley, 2010). However, SPCs’ performance on direct customer visits (customer relations) is low. Visiting customers, to offer them adequate after-sales service, is a major generator of revenue, profit and competency in modern competitive markets (Cohen and Kunreuther, 2007; Cohen et al., 2006).

Nevertheless, in most cases, SPCs do not have experience in after-sales service which is a common limitation of small businesses and marketing cooperatives in D&E economies. SPCs should give priority to customer-focused marketing activities, which also is the main concern for IOFs.

Significant variations were observed between high and low performing SPCs in supplying the large quantities of higher quality seed to the market that customers need. Quality seeds in this context refers to seeds that have desirable agronomic (for example, yield) and quality (for example, colour, texture, size) attributes that final customers (farmers) want (Thijssen et al., 2008). Seed is a complex business that requires special skills, experience and high level of commitment to provide quality seed for customers. It is closely interlinked with the farm management skills of member farmers and leaders’ commitment in motivating members and integrating various activities. The knowledge and skills on

seed production techniques are the determinant factors for the better performance of SPCs (Subedi and Borman, 2013).

In general Ethiopian SPCs show little marketing activities associated with competition, though we found significant variations between high and low performing SPCs in implementing competitor-focused marketing activities. Low performing SPCs do not bother about competitors and have very limited practices in competitor-related marketing activities. Concerning price, for example, they do not try to set the seed price by considering competitors’ price. High performing SPCs have experience in supplying diversified and unique crops (seeds) indicating their attempt to differentiate products. SPCs need to pay attention to competition, if they want to perform well in competitive markets.

To improve performance, SPCs should develop better relationship with suppliers. Our findings show that, in general, high performing SPCs have better relationships with input suppliers (i.e. in particular basic seed) than low performing SPCs. In seed business context of D&E economies like Ethiopia where the public organizations are responsible for development of new seeds, basic seed shortage is a major challenge both for small as well as large seed enterprises. Without reliable seed supply sources, it is difficult to continue a smooth operation of the seed business. Thus, for SPCs approaching and working with these seed suppliers is the only possible solution to access seed. SPCs having strong relationships with suppliers can enhance their market share and meet the quality standards set forth to satisfy the needs of their customers. The activities of the firms towards supplier orientation can improve their marketing activities and enhance performance (Asare et al., 2013; Hassan et al., 2014; Schiele, 2012).

The non-significant difference between high and low performing SPCs in sharing information within the cooperative shows the presence of common cultural practices of SPCs in this regard. SPCs practice sharing information regardless of their level of performance. The most probable explanation for this is that the presence of high social network and high level of embeddedness culture in the study context i.e. which is a typical feature of D&E economies (Steenkamp, 2005). Members of the cooperatives share information using both formal and informal mechanisms. Since members are living in the same village and have common social interests, they use all the possible opportunities (religious festivities, social gatherings etc.) for sharing information.

This study shows a clear difference between high and low performing SPCs in the implementation of marketing activities revealing marketing activities as CSFs. The strong association between intensity and quality of execution for individual marketing activities shows that intensity results in quality of execution in the Ethiopian SPCs context. The effect of intensity and quality cannot be disentangled in the Ethiopian SPCs context.

Low performing SPCs implement marketing activities less frequently than high performing SPCs, except for sharing information within the SPCs, which is a common practice for all SPCs regardless of their level of performance. In general, Ethiopian SPCs performed well on marketing activities related to interfunctional co-ordination, but poorly implemented activities associated with competitor orientation.

The study reveals that the implementation of key marketing activities is crucial for the sustainable competitive advantage of SPCs in Ethiopia. Our findings suggest that SPCs are likely to perform better if they use a variety of marketing activities focussed on customers, suppliers and competitors and inter-committees integration.

More specifically, Ethiopian SPCs have to give due attention to the implementation of marketing activities related to quality control, product diversification, assessment of customers and competitors, motivation and integration of activities by leaders, and maintenance of relations with suppliers.

Hence, the study lends support to the assertion that SPCs need to strengthen their capabilities to combine and coordinate their resources in an efficient way in order to execute the marketing activities. Moreover, government organizations, NGOs and seed related projects could play an important role in strengthening the capabilities of the SPCs to perform marketing activities that enhance their performance.

The current study has several managerial implications for SPCs, government organizations, NGOs, seed related development projects, and policy (decision) makers. It identifies key marketing activities that can strengthen the performance of Ethiopian SPCs.

First, SPCs should focus on the key marketing activities that have significant contribution to their performance. These activities could be controllable and managed by SPCs themselves. Thus, they should adjust their internal strengths and capabilities to the external opportunities. Second, marketing activities of SPCs related to competition are minimal.

The emergence of other seed producers (seed co-operatives, seed unions, private seed companies, public seed enterprises) is a challenge for the success of the cooperatives’ seed business. They should realize that they are in a dynamic and competitive market environment.

Hence, SPCs should understand the influence of competitors and give due attention to those marketing activities. Third, government organizations, NGOs and seed related projects play an important role in strengthening the capacity of the SPCs. They should consider the marketing activities identified in this study as CSFs. Government organizations should give special consideration to SPCs in accessing basic seed from suppliers considering their key contribution in improving the seed security of the country at large and serving the farming community in particular.

LIMITATIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The study has limitations that should be addressed. It was conducted among small seed cooperatives in the Ethiopian context and the marketing activities may only be CSFs for this specific business environment. Hence, it would be worth to conduct cross-cooperative sector studies. This study also used expert judgement which can be considered (more) objective. However, it is suggested that future research may consider more objective criteria to complement.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ahmet CA (1993). The impact of key internal factors on firm performance: an empirical study of small Turkish firms. J. Small Bus. Mgt. 31:86-92.

|

|

|

|

Amberg M, Fischl F, Wiener M (2005). Background of critical success factor research. Working paper no. 2/2005. Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Germany.

|

|

|

|

|

Appiah-Adu K (1998). Marketing activities and business performance: evidence from foreign and domestic manufacturing firms in a liberalized developing economy. Market. Intell. Plann. 16(7):436-442.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Appiah-Adu K, Fyall A, Singh S (2001). Marketing effectiveness and business performance in the financial services industry. J. Serv. Market. 15(1):18-34.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Asare KA, Brashear TG, Yang F, Kang F (2013). The relationship between supplier and development and firm performance: the mediating role of marketing process improvement. J. Bus. Ind. Market. 28(6):523-532.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Atuahene-Gima K (1996). Market orientation and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 35(2):93-103.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Baker WE, Sinkula JM (1999). The synergistic effect of market orientation and learning orientation on organizational performance. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 27:411-427.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bansal HS, Mendelson MB, Sharma B (2001). The impact of internal marketing activities on external marketing outcomes. J. Qual. Manage. 6(1):61-76.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Barney JB (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manage. 17(1):99-120.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bharadwaj SG, Varadarajan PR, Fahy J (1993). Sustainable competitive advantage in service industries: a conceptual model and research propositions. J. Market. 57:83-89.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bingham CB, Eisenhardt KM, Furr NR (2007). What makes a process a capability? Heuristics, strategy, and effective capture of opportunities. Strat. Entrep. J. 1(1-2):27-47.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Boohene R, Agyapong D, Asomaning R (2012). A micro level analysis of the market orientation-small business financial performance nexus. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2(1):31-43.

|

|

|

|

|

Brotherton B (2004). Critical success factors in UK budget hotel operations. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manage. 24(9):944-969.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bullen CV, Rockart JF (1981). A Primer on critical success factors. Centre for Information Systems Research, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

|

|

|

|

|

Campbell A, Whitehead J, Finkelstein S (2009). Why good leaders make bad decisions. Harv. Bus. Rev. pp.60-69.

|

|

|

|

|

Cano C, Carrillat F, Jaramillo F (2004). A meta-analysis of the relationship between market orientation and business performance: evidence from five continents. Int. J. Res. Mark. 21:179-200.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Caralli RA (2004). The Critical Success Factor Method: Establishing a Foundation for Enterprise Security Management (CMU/SEI-2004-TR-010). Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon University.

|

|

|

|

|

Carmeli A, Gelbard R, Gefen D (2010). The importance of innovation leadership in cultivating strategic fit and enhancing firm performance. Leadersh. Quart. 21:339-349.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chen Y, Jermias J (2014). Business strategy, executive compensation and firm performance. Account. Financ. 54:113-134.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chi CG, Gursoy D (2009). Employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and financial performance: an empirical examination. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 28(2):245-253.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cohen MA, Kunreuther H (2007). Operations risk management: overview of Paul Kleindorfer's contributions. Prod. Oper. Manag. 6(5):525-541.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cohen MA, Agrawal N, Agrawal V (2006). Winning in the aftermarket. Harv. Bus. Rev. 84(5):129-138.

|

|

|

|

|

Cooper RG, Kleinschmidt EJ (1993). New-product success in the chemical industry. Ind. Market. Manag. 22:85-99.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dadashzadeh M (1989). Teaching MIS concepts to MBA students: a critical success factor approach. J. Inform. Syst. Educ. 1(4).

|

|

|

|

|

Day GS (1994). The capabilities of market-driven firms. J. Market. 58:37-52.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Droge C, Vickery S, Markland RE (1994). Sources and outcomes of competitive advantage: an exploratory study in the furniture industry. Decis. Sci. 25(5/6):669-689.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dunn M, Birley S, Norburn D (1986). The marketing concept and the smaller firm. Market. Intell. Plann. 4(3):3-11.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dutta S, Narasimhan O, Rajiv S (2005). Conceptualizing and measuring capabilities: methodology and empirical application. Strateg. Manage. J. 26:277-285.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eisenhardt KM, Martin JA (2000). Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strateg. Manage. J. 21:1105-1121.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Forman H, Hunt JM (2005). Managing the influence of internal and external determinants on international industrial pricing strategies. Ind. Market. Manag. 34:133-146.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Freund YP (1988). Critical success factors. Plann. Rev.16(4):20-25.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gatignon H, Xuereb J-M (1997). Strategic orientation of the firm and new product performance. J. Market. Res. 34(1):77-90.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gemunden HG, Heydebreck P (1995). The influence of business strategies on technological network activities. Res. Policy 24:831-849.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Grwambi B, Ingenbleek P, Obi A, Schipper RA, van Trijp, HCM (2016). Towards achieving sustainable market access by South African smallholder deciduous fruit producers: the road ahead. In Bijman, J. and Bitzer, V (Eds.), Quality and Innovation in Food Chains-lessons and insights from Africa pp. 213-236.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Han JK, Kim N, Srivastava RK (1998). Market orientation and organizational performance: is innovation a missing link? J. Market. 62(4):30-45.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hansen G, Wernerfelt B (1989). Determinants of firm performance: the relative importance of economic and organisational factors. Strateg. Manage. J. 10(5):399-411.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hassan TR, Habib A, Khalid M (2014). Role of buyer-supplier relationship on buying firm's performance in chemical sector of Pakistan. Eur. J. Bus. Manage. 6(28):51-57.

|

|

|

|

|

Helfat CE, Peteraf MA (2003). The dynamic resource-based view: capability lifecycles. Strateg. Manage. J. 24:997-1010.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hilal MIM, Mubarak KM (2014). Market orientation adoption strategies for small restaurants: a study in the Eastern Sri Lanka. J. Manage. VIII(1):14-26.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Holcombe RG (2003). The origins of entrepreneurial opportunities. Rev. Austrian Econ. 16:25-43.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hult GTM, Kitchen DJ, Slater SF (2005). Market orientation and performance: an integration of disparate approaches. Strateg. Manage. J. 26:1173-1181.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hunt SD, Morgan RM (1995). The competitive advantage theory of competition. J. Market. 59:1-15.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ingram H, Biermann K, Cannon J, Neil J, Waddle C (2000). Internalizing action learning: a company perspective. Establishing critical success factors for action learning courses. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. M. 12(2):107-113.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jameson SM (2000). Recruitment and training in small firms. J. Eur. Ind. Training. 24(1):43-49.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jaworski BJ, Kohli AK (1993). Market orientation: antecedents and consequences. J. Market. 57:53-70.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jorge CR, Sérgio TM, João R (2012). Marketing activities, market orientation and other market variables influence on SMEs performance. In conference proceedings of 41st EMAC conference-marketing to citizens-going beyond customers and consumers. Lisboa: ISCTE.

|

|

|

|

|

Joung H-W, Goh BK, Huffman L, Jingxue JY, Surles J (2015). Investigating relationships between internal marketing practices and employee organizational commitment in the foodservice industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. M. 27(7):1618-1640.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Katsikeas CS, Morgan NA, Leonidou LC, Hult GTM (2016). Assessing performance outcomes in marketing. J. Market. 80:1-20.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ketchen DJ, Hult GTM, Slater SF (2007). Toward greater understanding of market orientation and the resource-based view. Strateg. Manage. J. 28:961-964.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kim AJ, Ko E (2011). Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. J. Bus. Res. 65:1480-1486.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kirca AH, Jayachandran S, Bearden WO (2005). Market orientation: a meta-analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and impact on performance. J. Market. 69:24-41.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kouzes JM, Posner BZ (2012). Leadership challenge (5th ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

|

|

|

|

|

Kumar V, Jones E, Venkatesan R, Leone RP (2011). Is market orientation a source of sustainable competitive advantage or simply the cost of competing? J. Market. 75:16-30.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Langerak F, Hultink EJ, Robben HSJ (2004). The impact of market orientation, product advantage, and launch proficiency on new product performance and organizational performance. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 21:79-94.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Leidecker J, Bruno A (1984). Identifying and using critical success factors. Long Range Plann. 17(1):23-32.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lengnick-Hall CA, Wolff JA (1999). Similarities and contradictions in the core logic of three strategy research streams. Strateg. Manage. J. 20(12):1109-1132.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Liargovas PG, Skandalis KS (2010). Factors affecting firms' performance: the case of Greece. Global Bus. Manage. Res. 2(2&3):184-197.

|

|

|

|

|

Lin Y, Wu Lei-Yu (2012). Exploring the role of dynamic capabilities in firm performance under the resource-based view framework. J. Bus. Res. 67(3):407-413.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lings IN, Greenley EG (2010). Internal market orientation and market-oriented behaviours. J. Serv. Manage. 21(3):321-343.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lynch DF, Keller SB, Ozment J (2000). The effect of logistics capabilities and strategy on firm performance. J. Bus. Logist. 21(2):47-67.

|

|

|

|

|

Makadok R (2001). Toward a synthesis of the resource based and dynamic-capability views of rent creation. Strateg. Manage. J. 22(5):387-401.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Martin R (2007). How successful leaders think. Harv. Bus. Rev. pp.60-67.

|

|

|

|

|

Menguc B, Auh S (2006). Creating a firm-level dynamic capability through capitalizing on market orientation and innovativeness. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 34(1):63-73.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mokhtar SSM, Yusoff RZ, Arshad R (2009). Market orientation critical success factors of Malaysian manufacturers and its impact on financial performance. Int. J. Market. Stud. 1(1):77-84.

|

|

|

|

|

Moorman C (1995). Organizational information processes: cultural antecedents and new product outcomes. J. Market. Res. 32(3):318-335

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Moorman C, Slotegraaf RJ (1999). The contingency value of complementary capabilities in product development. J. Market. Res. 36:239-257.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Morgan NA (2012). Marketing and business performance. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 40(1):102-119.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Morgan NA, Vorhies DW, Mason CH (2009). Market orientation, marketing capabilities, and firm performance. Strateg. Manage. J. 30:909-920.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Morgan NA, Zou S, Vorhies DW, Katsikeas CS (2003). Experiential and informational knowledge, architectural marketing capabilities, and the adaptive performance of export ventures. Decis. Sci. 34(2):287-321.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Narver JC, Slater SF (1990). The effect of market orientation on business profitability. J. Market. 54(10):20-35.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nath P, Nachiappan S, Ramanathan R (2010). The impact of marketing capability, operations capability and diversification strategy on performance: a resource-based view. Ind. Market. Manag. 39(2):317-329.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Newbert SL (2007). Empirical research on the resource based view of the firm: an assessment and suggestions for future research. Strateg. Manage. J. 28(2):121-146.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pinto J, Slevin D (1987). Critical factors in successful project implementation. IEEE T. Eng. Manage. 34(1):22-27.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Porter MP (1980). Competitive strategy: techniques for analysing industries and competitors. New York: Free Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Priem RL, Butler JE (2001). Is the resource-based 'view' a useful perspective for strategic management research? Acad. Manage. Rev. 26(1):22-40.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Puni A, Ofei SB, Okoe A (2014). The effect of leadership styles on firm performance in Ghana. Int. J. Market. Stud. 6(1):177-185.

|

|

|

|

|

Rahman S (2001). Total quality management practices and business outcome: evidence from small and medium enterprises in Western Australia. Total Qual. Manage. 12(2):201-210.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rockart J (1979). Chief executives define their own information needs. Harvard Bus. Rev. pp.81-92.

|

|

|

|

|

Rust RT, Ambler T, Carpenter GS, Kumar V, Srivastava RK (2004). Measuring marketing productivity: current knowledge and future directions. J. Market. 68:76-89.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Saraph JV, Benson PG, Schroeder RG (1989). An instrument for measuring the critical factors of quality management. Decis. Sci. 20(4):810-829.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schiele H (2012). Accessing supplier innovation by being their preferred customer. Res. Technol. Manage. 55:44-50.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Scott-Young C, Samson D (2008). Project success and project team management: evidence from capital projects in the process industries. J. Oper. Manag. 26(6):749-766.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Selim HM (2007). Critical success factors for e-learning acceptance: confirmatory factor models. Comput. Educ. 49:396-413.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Siu W (2002). Marketing activities and performance: a comparison of the Internet-based and traditional small firms in Taiwan. Ind. Market. Manag. 31:177-188.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Srivastava RK, Shervani TA, Fahey L (1998). Market-based assets and shareholder value: a framework for analysis. J. Market. 62(1):2-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Steenkamp JEM (2005). Moving out of the U.S. silo: a call to arms for conducting international marketing research. J. Mark. 69:6-8.

|

|

|

|

|

Subedi A, Borman G (2013). Critical success factors for local seed business: report on the 2012 assessment. Centre for Development Innovation, Wageningen UR, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

|

|

|

|

|

Teece DJ, Pisano G, Shuen A (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manage. J. 18(7):509-535.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Theodosiou M, Kehagias J, Katsikea E (2012). Strategic orientations, marketing capabilities and firm performance: an empirical investigation in the context of frontline managers in service organizations. Ind. Market. Manag. 41(7):1058-1070.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Thijssen MH, Bishaw Z, Beshir A, de Boef WS (2008). (Eds.) Farmers, seeds and varieties: supporting informal seed supply in Ethiopia. Wageningen, Wageningen International. 348 p.

|

|

|

|

|