ABSTRACT

In the Brazilian contemporaneous context, there is evidence of society's demands for companies to carry out their activities in a responsible manner in the social and environmental spheres. In the coal mining industry, the debate is even more eminent because of the significant environmental impacts generated by the mining activity. The present study aims to analyze the determinants of socio-environmental practices of coal companies in the South of Santa Catarina (SC) and Rio Grande do Sul (RS) in the perceptions of company managers and institutions by these actions, under the perspective of social capital. The research is empirical and is supported by a descriptive qualitative approach, using documentary analysis and interview as a data collection technique. From the point of view of the research strategy, it consists of a multicase study. Managers from two national and private capital companies were interviewed, with importance on their economic area in SC and RS, respectively: Copelmi Mineração Ltda and Carbonífera Catarinense Ltda. Managers of two institutions benefited by the actions of the respective companies, which characterize social-environmental responsibility related to theories of social capital. The results demonstrated empirical evidence of social capital constituted in the existence of networks of relationship between the companies and the institutions impacted with focus on the reciprocity. It was detected that the synergy among those involved, as a motivation for social and environmental actions, produces improvement in the search for quality of life and in the training of the impacted.

Key words: Social responsibility, social and environmental actions, social and environmental determinants, share capital, social actions.

Contemporary society has experienced local, national and international movements of concern with socio-environmental problems. Caused mostly by human intervention, by the finding of possibility of ecological imbalance and the planet's life, the problematic has gained ample space in the academic environment (Silva et al., 2011). This movement is noticeable in several fields of activity, in the field of education, service provision and production of consumer goods, among others. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Social and Environmental Responsibility (SER), at the present time, appear as important managerial instruments in the realignment of organizational strategies, aiming at a more participative economy and engaged in socio-environmental problems.

SER is linked to actions that promote the preservation of the environment with a focus on sustainability and development with quality of life. The complexity of the theme is challenging and overcoming it implies in the alignment of initiatives, integration and socialization of policies and practices, together with the strategic positioning of organizations that continuously seek economic efficiency in the face of the uncertainties of the globalized market.

Of course, strategies adopted by companies implicitly characterize the quest to legitimize themselves before society, within the scope of social and environmental responsibility, and infer in maintaining or expanding their reputation in the socially and ecologically correct business market. For Barbieri (2012) and Tinoco (2000), environmental responsibility in management is a system of organizational nature, characterized by guidelines, administrative and operational activities that promote control over the environmental impact of productive activity. Thus, it aims to achieve positive effects on the environment, either by avoiding, reducing or eliminating the impacts caused by man's actions on the living environment, aiming at the promotion of an ecologically balanced environment. Therefore, environmental responsibility is a set of individuals, collective or entrepreneurial attitudes that aim at the sustainable development of the environment. For Tachizawa and Pozo (2017), environmental management is an important managerial tool for training and creating conditions of competitiveness for organizations, regardless of their economic activity.

In this context, the social capital of institutions and communities conceptualized by Bourdieu and Miceli (1974) as the set of real or potential resources, linked to a network of inter-knowledge and recognition relationships, which can be perceived by peers, indicate gains in collective efficiency and cohesion. groups. It contributes to promoting economic development, strengthening community solidarity, through expectations of reciprocity and application of social norms. As Putnam (1995) states, from the studies carried out, the differences between institutional performance and development of the regions analyzed were related to a greater presence of social capital.

The triad - networks, norms and trust - are the features of social life that constitute social capital, defined by Putnam (1995). They are resources that are part of social relations and facilitate the promotion of actions in pursuit of common goals for the subjects involved. Observed in reciprocity, trust, norms, association and cooperation relations, between communities, associations, cooperatives, clubs, business sectors, among others, that promote actions based on altruism in the short term and long-term objectives, enabling the obtaining of profits economic, political and social. However, historically, different manifestations of social capital have enabled the reflection that “we cannot assume that this capital has to be something good always and everywhere” (Putnam, 2003: 15).

Coal is the most widely available fossil fuel in the world. The proved reserves in 2008, was around 847.5 billion tons, enough to meet the current world demand for approximately 130 years. Proved coal reserves in the world are in 75 countries. From the existing reserves, 75% are in only five countries, the United States, Russia, China, Australia and India. The world coal supply in 2013 did not show significant growth compared to the previous year (Araújo, 2018). In Brazil, the main coal reserves (99.66%) are (10.41%) and RS (89.25%), with only 0.02% in São Paulo and 0.32% in Paraná (ANEEL, 2008). In 2002, national coal reserves were around 12 billion tons, which corresponds to more than 50% of the South American reserves and 1.2% of the world reserves. In 2003, the ore accounted for 6.6% of the Brazilian energy matrix and, in 2007, approximately 1.5% of the Brazilian electric power matrix. Among the restrictions are the high levels of ash and sulfur, the main factors for the low rate of utilization of coal in Brazil. In 2007, when 435.68 TWh was produced in the country, coal was responsible for the generation of 7.9 TWh, from the operation of thermoelectric plants that are in the southern region, in the vicinity of the mining areas (ANEEL, 2008).

In SC, the Carboniferous Basin "consists of an approximate range of one hundred kilometers in length and an average width of twenty kilometers, between the Serra Geral to the West and the granitic massif of the Serra do Mar to the East, following the North-South orientation” (Belolli et al., 2002). The most important coal mining centers in Santa Catarina are in the municipalities of Lauro Müller, Urussanga, Siderópolis, Treviso, Criciúma, Forquilhinha, Içara, Morro da Fumaça and Maracajá. In RS, which holds the most significant national reserve of coal - 89.25%, a total of 28,802 million tons - the coal region is in the area of Baixo Jacuí. The mineral deposit of Candiota (RS) alone owns 38% of all national coal (ABCM, 2018). However, the ore is poor from the energy point of view and does not allow beneficiation or transportation, due to the high content of impurities. This makes it to be done without processing and at the mouth of the mine (ANEEL, 2008).

In the research carried out with managers from two coal miners (CARB1 and CARB2) and the benefited two community institutions (IMP1 and IMP2), we interviewed six managers. We verified that CARB1 is a closed (private), private and family-owned company. It currently has a mining unit, located in Lauro Muller (SC). We interviewed two managers (A1 and A2) who are responsible for Human Resources (social worker and organizational psychologist). The manager (B1) of the community institution (IMP1) impacted by the social-environmental actions of CARB 1 is its president. IMP1 is in Lauro Muller (SC). It is a non-profit organization, managed by the community where it is inserted and has been active for more than 15 years, since November 14, 2003.

CARB 2 is a national privately held company (limited liability). It is located as the largest coal mining company in Brazil, with six mining units. The research was developed in the unit located in Butiá (RS). The interviewed managers (C1 and C2) work in environmental management and public relations of the company. Manager (D1) of the community institution (IMP2) impacted by the social-environmental actions of CARB 2 is vice-president of the same. It is an association of residents located in the neighborhood where the mining company CARB 2 develops coal mining activities. The managers of the coal companies are employees and, of the impacted ones, they are volunteers.

This context is strengthened in the coal mining industry due to the environmental impacts generated by this mining activity. Relevant in the Brazilian energy matrix, from a strategic, economic and social point of view, the exploitation of this and other natural resources is a condition for the survival of this and future generations and must be reconciled with the right to the quality of the living environment. Thus, in the context of coal mining, the organizational strategies must be related to the reduction of the environmental damage caused by the economic activity, with the promotion of programs and projects for the benefit of the community where companies operate. In these complex economic relations, the social capital constituted by practices mitigating these impacts can generate mutual benefits through the establishment of networks, effects of reciprocity, cooperation, protective standards and trust. Thus, the following questions are proposed as guiding the development of the study:

(i) What are the determining factors for socioenvironmental practices of the managers of companies in the coal sector in southern Brazil?

(ii) What are the perceptions of agents directly impacted by these practices?

According to the recommendation of Light and Dana. (2013) this study contributes to analyzing social capital in the socio-environmental context. The objective was to analyze socio-environmental practices of coal companies in SC and RS; the perception of managers and community institutions, directly impacted by these actions, from the perspective of social capital. Given the scarcity of previous studies, this study contributes to increase evidence in academic production relating to socio-environmental organizational practices and their implications in the social life of affected communities, based on the view of social capital.

Corporate social-environmental responsibility

The definition of CSR dates to a long period, but studies have proliferated since the twentieth century (Carroll, 1999). The 1976 Nobel Prize in Economics, Milton Friedman, according to Ferrell et al. (2000) represents one of the main authors who wrote about CSR. He advocated the idea that socially responsible companies are those that primarily serve the interests of their shareholders, seeking to maximize their profits. For Carroll (1979: 500), the definitions of CSR that infer the responsibility of the companies to generate profits and to comply with laws needed extension of the concept in the scope of the society. “Corporate social responsibility covers the economic, legal, ethical and discretionary expectations society has of organizations at a given point in time”. Society has expectations that organizations, in addition to generating profit from their activities, through the production and sale of goods and services that will benefit the individuals of that society must obey the laws, have ethical attitudes towards their duties, their rights, promote voluntary actions and practice philanthropic actions, recognize the economic responsibility (to be profitable) as being fundamental and a foundation for the other.

Ferrell et al. (2000) affirm that CSR, or social responsibility in the business world, consists of a company's obligation to maximize its positive impact on stakeholders and to minimize the negative, both internally and externally. In the north, socio-environmental development is based on the principle of sustainable development. It is characterized by actions or effects related to the process of growth, evolution, related to the social and environmental conditioners - an economically viable, socially just and environmentally sustainable society. It is understood that the economic variables and the degree of local development are not directly related, that is, economic growth does not necessarily produce development. It is an essential element for development; however, it is not enough. According to Araujo (2003), social, cultural and political factors that are not regulated exclusively by the market system promote development.

Thus, social and environmental development is directly related to the SER of individuals, organizations and governments. Social responsibility is seen not only as a concept, but also as a personal and collective value, which reflects in the actions of a company, both of its managers and of its employees (Ponchirolli, 2007). The contemporary economic scenario presents new and challenging scenarios for organizations. Companies need to worry about profit and bring answers to their shareholders, but at the same time, there is a growing concern with the social and environmental impacts that are consequences of their actions.

According to Tachizawa and Andrade (2008), the behavior of consumers today has created the need for new relationships with organizations worldwide, outlining the contours of a new economic order. This new context is characterized by a rigid clientele, which is concerned with interacting with companies that are ethical, that have a good institutional image in the market and that act socially in a responsible way. The expansion of the collective consciousness, with respect to the environment and the complexity of the social demands that the community passes on to the organizations, induce a new position on the part of businessmen and executives facing such issues. According to Tachizawa and Pozo (2009), population is no longer concerned only with the final product, but also with the entire manufacturing process, from compliance with legislation, respect for the environment and concern with the society in which the company is inserted. Nowadays, more and more companies need to worry about socio-environmental risks, doing their best to minimize them. The transformations and ecological influence in business are increasingly observable and with ever deeper economic effects. For Tachizawa (2005: 6), “organizations that take integrated strategic decisions on the environmental and ecological issues will achieve significant competitive advantages, if not, reduction of costs and increase in profits in the medium and long terms”. In this context, at the present time, environmental management and social responsibility are“important management tools for training and creating conditions of competitiveness for organizations, regardless of their economic segment” (Tachizawa, 2005: 6).

According to Tachizawa (2005), environmental management and social responsibility are important management tools for the creation of competitiveness between companies. Investment in environmental management and social responsibility is the natural response of companies to the new customer, the green and ecologically correct consumer. Large companies help their suppliers improve their eco-friendly marketing and management practices, because they consider them as part of their productive chain (Tachizawa and Andrade, 2008). This external pressure that companies suffer for better market quality is represented by legal certificates, such as: ISO 14000 and ISO 14001 (International Organization for Standardization), which deal with the Environmental Management System (EMS).

However, companies have usually practiced social responsibility and environmental responsibility - two of the dimensions of corporate sustainability - in a disengaged way, according to its area of operation and functionalities (Cohen et al., 2017). According to Barbieri (2012), environmental concerns in the business area, are influenced by three major sets of forces - government, society and the market - interacting with each other. Without social pressures and government measures, we would not observe the increasing involvement of companies in the environmental context. These are influencers of environmental legislation which, in general, result from the perception of the segments of the society on the environmental problems, and with this, they press the public state agents to see them solved. In addition, increasing awareness of the population in general and, above all, of consumers who increasingly seek to use environmentally sound products and services is another source of pressure on businesses.

For Schwartz and Carroll (2008: 149) several complementary frameworks appear to be in competition for pre-eminence in the field of business and society. They cite the prevalence of five frames: (a) corporate social responsibility; (b) business ethics; (c) stakeholder management; (d) sustainability; (e) corporate citizenship. However, they assert that “difficulties remain in understanding what each construct really means, or should mean, and how each can relate to others”. The concepts of ethics and social responsibility in business, according to Ferrell et al. (2000: 68), are often used as synonyms, but the two expressions have different meanings: “Business ethics includes principles and standards that guide behavior in the business world”.

Two of the five constructs cited by Schwartz and Carroll (2008) in society and business, they claim to be CSR, probably, the most widely used construct as an explicit structure to better understand the relationship between business and society. With its original focus on reducing negative social impacts, it seemed to change over time to the more general notion of “doing good” for society. Although there are questions about these constructs having adequate theoretical or practical legitimacy, they consider that this situation seems to have changed considerably in the present. Thus, the concept of socio-environmental development is related to the integration between the economy, society and the environment, in order to achieve economic growth, with social inclusion and environmental protection.

According to Ponchirolli (2007), the initial dimension of the CSR exercise is associated with philanthropic actions, but it does not end there. In this dimension, the main characteristic is the spontaneous generosity of the entrepreneur, which reflects in donations to charitable and philanthropic entities. The second dimension of the CSR exercise is related to corporate citizenship, direct social actions with the community. In these fields of activity, socially responsible companies place financial resources at the service of the community, products, services and know-how of the organization and its employees (Ponchirolli, 2007).

However, according to Bruch and Walter (2005), although the strategic relevance of corporate philanthropy is widely accepted, their effectiveness varies substantially. Investments in this area without a cohesive strategy and conducted in a fragmented way often dissipate. Only philanthropic activities that create true value for the beneficiaries and improve the company's business performance are sustainable in the long term. Actions that do not fit these two goals are easily threatened in difficult economic situations. Corporate social actions generate some corporate advantage when social impacts are long lasting, sustainable and with significant economic returns to their philanthropy, but few companies can achieve these goals. In most cases, executives dismiss this ineffectiveness as an inevitable part of their philanthropic engagement, viewed effectively as charitable activity.

Society, in general, and some sectors of it, in particular, has expanded the questioning of the mining sector about its legacy, which according to Dias et al. (2013), constitute: environmental and social impacts, historical liabilities, market fluctuations and externalities of the macroeconomic scenario, logistics, operating costs, human rights issues, chronic labor shortages, risk management and value chain impacts, compensation criteria and social investment. These are some indicators of interest for social actors such as clients, shareholders, investors, government authorities, the labor force, the community, civil society organizations and trade unions.

In this sense, social and environmental factors can interfere in the implementation of the business plans of mining companies operating in Brazil. Thus, in a gradual way, they internalize in their decision-making processes the indicators that, until then, were not part of them. The companies of the sector have expanded the adoption of management practices with articulation of different environmental, economic and social aspects, in view of the scrutiny of interested parties, evolution of the regulatory framework and implementation of corporate commitments (Dias et al., 2013).

Social and environmental responsibility and social capital

Dabul (2017: 61), when investigating motivations (business cases) for adopting these good practices, cites that the majority was related to the improvement of the financial performance, through increase of revenues or reduction of costs placed as instrumental motivations. Expected financial results focus on cost reduction and revenue growth: the motivations for cost reduction are associated with “eco-efficiency, risk reduction, fines costs, boycotts, regulation, fundraising, employee recruitment” and to increase revenues, “product differentiation, employee excellence, competitive advantage, increased margins”. However, in addition to these, there are also motivations not as easily tangible as reputation, legitimacy, image and social license to operate. Thus, it emerges in this scenario, indicators of social capital to be constituted from the relationships established between the various economic, social and political instances, in contemporaneity. The concept of social capital, according to Ferraz et al. (2011), incorporates meanings in various theoretical and methodological orientations. It is used by sociologists, anthropologists, economists, political scientists and theorists of macroeconomic and social development. In contemporary times, the theme has been gaining space in several areas. Brito (2006, p. 36) cites that“[...] the concept ended up being incorporated into the discourse of international organizations that work to promote development, such as the World Bank, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) or the United Nations Development Program (UNDP)”.

However, the expression social capital gained a projection from the end of the 20th century, in the 1990s, with the studies by Bourdieu (1998), Coleman (1988; 1990), Putnam (1993; 1995; 2003) and Fukuyama (1996; 2000). The main results of the studies indicate gains in collective efficiency and cohesion of the groups, inferring better performance of communities and institutions, and contributing to the promotion of economic development (Santos, 2003). In these works, they highlight the existence, in each territorial space, of social characteristics associated with productive purposes, such as: generalized trust in the other; acting in associations; the ability to coordinate complex social networks; among others. The notion of social capital popularized the argument of the social dimension as central factor for the explanation of economic development. This was based “on the consequences of the social economy, that is, the side effects derived from the interaction of social networks and not from actions of individuals seeking self-interest” (Ferrarezi, 2003: 7).

Conceptions of social capital emerge in the context of an individual and public good. For Silva (2006), based on the concept of social capital by Bourdieu and Miceli (1974), a set of relationships and social networks that an individual has and all the resources that can be gathered using such relationships constitute their social capital. Thus, the social capital accumulated by a given individual will make it possible to obtain a position of advantage in a given group, relating this process to the questions of power. However, for Macke (2006), social capital is a public good belonging to a group, community or society, found in relationships between persons or groups. Fukuyama (2000) defines it as a set of values or informal norms common to members of a particular group that allows cooperation between them. These standards include reciprocity, honesty and responsibility in fulfilling obligations.

For Christoforou (2011), social capital is effective in norms and networks of reciprocity, trust and cooperation that facilitate coordinated action for mutual benefit. It states that theoretical and empirical studies have documented the positive contribution of social capital to social well-being and to the development of societies. The studies by Onyx and Bullen (2000) are also based on the analysis of social capital in terms of participation in networks, reciprocity, trust, social norms, common goods and social agency. Thus, according to Fukuyama (1996; 2000) and Christoforou (2011), social capital can influence the aspects related to the well-being of the individuals and the sustainability of a society. For Onyx and Bullen (2000), this influence is also related to the communities in the conversion of collaboration into productive force. Regarding this, Portes (1998) states that the purpose of social capital is to strengthen community solidarity through expectations of reciprocity and application of social norms.

Social capital is a strategic resource of organizations, and can influence performance, the competitive advantages and sustainability of an organization or even a network of organizations, according to Wu (2008). Milani (2004) attributes to social capital the relevance of an active indicator for local development, which is established based on the relations of cooperation and reciprocity between the subjects, interests and projects of the social, political and cultural nature. As reported by Wu (2008), information sharing plays a mediating role in the relations between improving the competitiveness of companies related to social capital.

However, historically, different manifestations of social capital have made it possible to reflect that this may not be “something good always and everywhere” (Putnam, 2003: 15). Thus, social capital may have negative externalities where norms and networks can also reproduce or increase political and economic inequalities, as stated by Ferrarezi (2003). Jordana (2000) also highlights the inconsistency in concluding that high levels of solidarity cause high economic results. Other variables can be inferred in the analyses, such as the ways in which institutions regulate access to credit and markets, or forms of political participation, functioning as an intermediate variable between social capital and income.

Bourdieu and Miceli (1974), Coleman (1998) and Putnam (2003) emphasize that social capital generates development and competitive advantage because it is an aggregator of values, norms, reciprocity and trust, both in the subjects and in the groups and in the networks formed between these groups, which enable them to act together more effectively. The conception of social capital and the ways in which it constitutes the development of the quality of living environments has been the focus of studies in the different areas of human performance. Due to the complexity of verifying the results of their applications, dimensions of analysis are established that aim to measure the effective performance of social capital with the communities, organizations and different groups involved.

Thus, besides the theories presented by Bourdieu et al. exposed so far, Nahapiet and Goshal (1998), in their work on the construct, understand that social capital basically consists of three analytical dimensions: structural dimension, relational dimension and cognitive dimension. They consider the constitution of social capital from the structures present in each environment (structural), relationships between individuals (relational) and in the common interests between them (cognitive). However, the authors emphasize the difficulty of promoting the fractional analysis of the dimensions. The three dimensions are thus closely related, which does not invalidate or even invalidate the classification, because its complementarity and interdependence facilitate the understanding of the construct. That is, they were created only to facilitate the understanding of the constitution of this strategic resource and the analysis of the benefits to the organizations (Jha and Cox, 2015).

For Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998), the contribution to structural social capital lies in the network connections and configurations and in the adequacy of the organization. For Vallejos et al. (2008), these would be in the bonds between the subjects, in the stability, in the density of the configurations and in the network connectivity. The structural dimension lies in the structures present in each environment. It refers to the connection pattern between the subjects and includes the network connections and configurations that describe the connection pattern in terms of measurement, such as density, connectivity, hierarchy and organizational suitability. Therefore, it is directly associated to the structure of the network, in the identification of the connections and, mainly, in the intentionality of the connections. The main benefit of the configuration of the collaboration network is the combination of information and the exchange of knowledge, because the network configuration is what determines the main channels of information (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998).

The relational dimension, according to Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998), is observed in the trust, norms, obligations and expectations and social identification. For Vallejos et al. (2008), trust, norms of reciprocity, participation, obligations and tolerance of diversity are associated. It refers to the assets that are created and potentialized through the relationship. The focus is not on the network configuration but on the content and characteristics of the network. They include attributes such as identification, trust, norms, sanctions, obligations and expectations. It therefore encompasses the relationships developed through a history of interactions, also cited as the norms, obligations, expectations and social identification of the group that interfere in this dimension. This dimension rests on the type of relationships that actors or social units develop, referring to each actor's individual relationship with other actors in the network and considering, in addition to the content transacted among the actors, the roles they can assume, such as friends, informants, confidants, teachers and technicians. For Putnam (2003) and Fukuyama (1996), all these factors are constituted from the historical roots of individuals and the constitution of the communities where they are inserted. In addition, according to Putnam (2003), virtuous citizens are helpful, respectful, and confident in each other, even when they differ on important matters.

The cognitive dimension of social capital, which is expressed by the common interests of individuals, originates from values, shared visions, and culture. For Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998), the contribution to cognitive social capital arises through the generation of the context, codes and language shared by the community in its narratives. It refers, therefore, to shared visions, interpretations, and systems of meanings, such as language, codes, and narratives. Shared culture, values, codes, languages and narratives are also cited by Vallejos et al. (2008) as providers of cognitive social capital. This dimension is associated with the sharing of goals, experiences, and a set of common values, meanings and vision that facilitate actions. These can benefit the entire organization and encourage the development of trusted relationships, implementation of new practices, facilitating the generation of new knowledge.

Research characterization

The research is configured as theoretical-empirical and is supported by a qualitative descriptive approach, using documentary analysis and interview as a technique of data collection. It is, therefore, in the analysis from the interdisciplinary perspective of the practices of socio-environmental, voluntary and obligatory actions implemented by the coal companies in the scope of the qualitative study. It is a qualitative approach, based on the assumption that the world is understood from the perception of the individuals inserted in the studied situations (Creswell, 2007). It enables the researcher to use diverse research strategies through interpretation, flexibilization and expansion of possibilities of action, while it intermediates the transformation of classified reality empirical science.

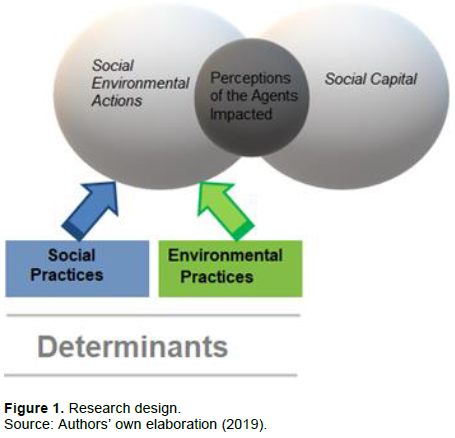

Figure 1 demonstrates the theoretical fields integrating research, which seeks to analyze the perceptions of impacted agents, through the union of aspects of social and environmental actions to social capital. From the point of view of the research strategy, it consists of a multiple-case study. The data collection was carried out in 2018-2019. Two national and private capital companies were chosen, with emphasis on their economic area in SC and RS, respectively: Carbonífera Catarinense Ltda and Copelmi Mineração Ltd. Both companies disclose their socio-environmental practices through their websites.

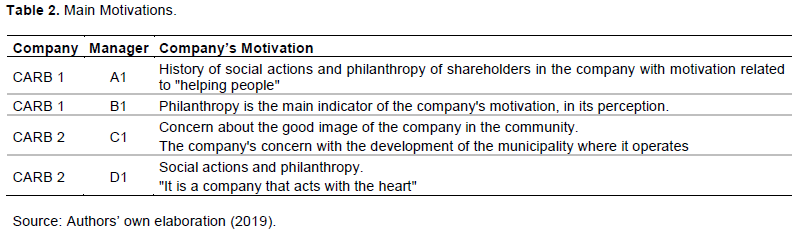

Due to the complexity of the economic activity related to the coal mining industry, the number of coal companies is limited to the deposits existing in the different municipalities. Thus, for the choice of companies operating in the coal mining industry, we opted for those that are linked to the Brazilian Mineral Coal Association (ABCM), located in the states of SC and RS. In SC, the coal companies are also linked to the Union of Coal Extraction Industry of the State of Santa Catarina (SIECESC). In the selection of the sample of the companies, the criterion related to the industrial area, period of operation in the market, productive potential and prominence in the two Brazilian states in the scope of extraction and commercialization of mineral coal was used. Therefore, the choice also fell on the size of the companies. Thus, taking as a starting point the objective of this research - which is to analyze the determinants of socio-environmental practices of coal companies in the south of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul and the perceptions of the agents directly impacted by these actions - the methodological aspects were defined. The interdisciplinarity of the study in question is highlighted in the interrelation of the determinants of socioenvironmental practices of carboniferous companies in the south of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul with perceptions of the agents directly impacted by these actions in the scope of socio-environmental responsibility. Thus, in the research, it is relevant to investigate the motivations, perceptions, interests and needs that support the positioning of organizations in relation to these issues (Table 2).

The interview was based on a semi-structured questionnaire with the managers of the companies and the managers of institutions impacted by the actions promoted. Two managers were interviewed, representatives of Carbonífera Catarinense Ltd, appointed in this study by respondents A1 and A2. Interviewee A1 has worked at the company as a social worker for 14 and a half years. Interviewee A2 works in management as an organizational psychologist and has been with the company for 4 years. Two representatives of the Copelmi Mineração Ltda. (C1 and C2) were interviewed. Interviewee C1 is an Environmental Engineer, has worked for the company for 6 and a half years. Interviewee C2 who has been in the public relations function, has worked in the same company for 45 years.

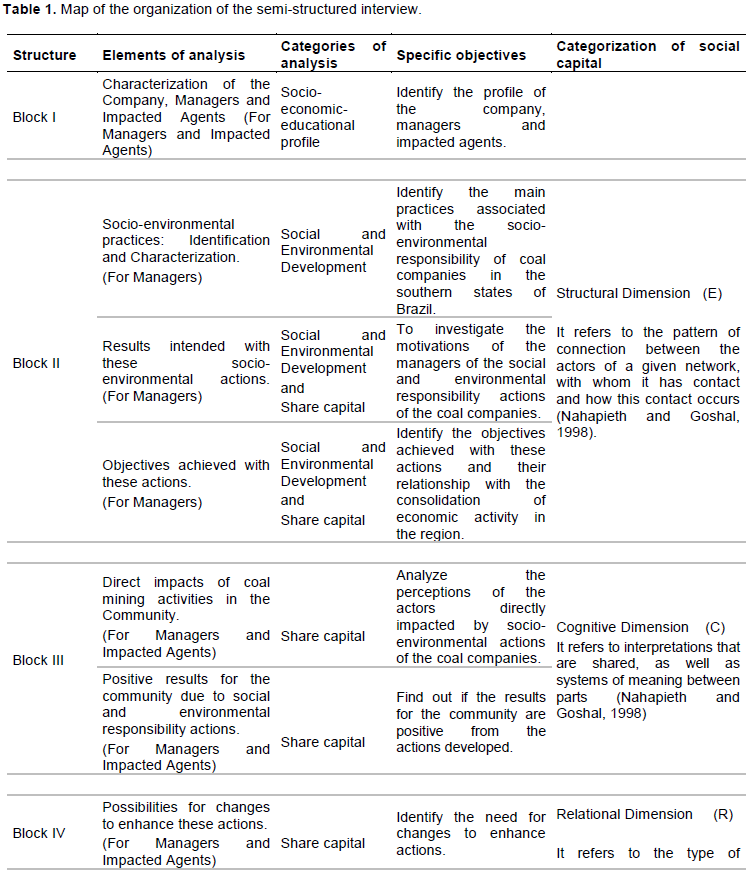

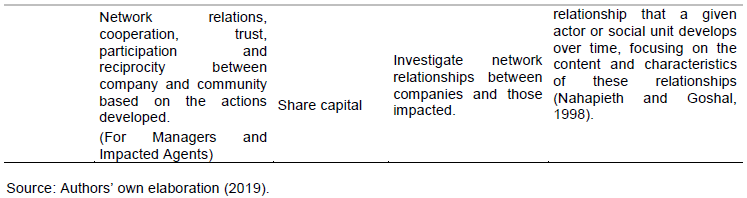

The semi-structured interviews, carried out with the managers of the coal companies and the managers of the institutions impacted by the actions of these companies, were organized in four blocks. In the first block, information was sought on the companies and managers interviewed. The following blocks were categorized based on three dimensions of Social Capital: Structural Dimension (E); Cognitive Dimension (C) and Relational Dimension (R). Likewise, within the scope of those impacted, the categorization was also located in the three dimensions mentioned of social capital (Nahapiet and Goshal, 1998).

In the development of the research, it was decided to analyze the discourse of the managers of the companies and those impacted by the actions of the same. It started by analyzing the discourse of the managers of the coal companies located in the State of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, named A and C and, later, of the institutions impacted by their actions, named B and D.

The elements and categories of analysis and the objectives and categorization of Social Capital are organized in Table 1. Considering the analysis categories emerging from the theoretical basis, a script was used to conduct the interviews (Appendix Table 1).

Research agents

COPELMI Mineração Ltda, located in the municipalities of Baixo Jacuí and Candiota, in RS, has been active in coal mining since 1998, but it originated historically from other companies that date from the beginning of mining in RS, in 1883 (Witkowski, 2005). The theme also emerges in the vision of company A, which states: “Extract and always benefit by prioritizing the well-being and safety of employees, in addition to maintaining respect for the environment”. Certified by NBR ISO 14.001 since 2005, the company is audited annually, maintaining its commitment to the continuous improvement of the Environmental Management System, “which covers the entire production complex, from coal extraction, through processing, to its transportation to the end customer” (CCL, 2018: 1).

The history of Carbonífera Catarinense Ltd begins in 1999 in the city of Lauro Muller, SC, when the opening of two mining units in the municipality began, which were named as Mina Bonito I and Mina Novo Horizonte. The largest private coal miner in the country, it owns 80% of the industrial market and 18% of the total domestic coal market (CML, 2018). For the manager of company Carbonífera Catarinense Ltd., the environmental issue is also a priority, in terms of the prevention and recovery of mined areas, enabling its future use. Company C's environmental management and occupational health and safety policy also includes, among other objectives, the identification and control of environmental aspects, minimizing the impacts associated with mining activity and the environmental recovery of the mined areas. It is also certified by NBR ISO 14.001, which complies with the company's environmental commitment (CML, 2018).

About impacted community institutions, we have chosen from the information provided on the websites of coal companies, as well as through interviews with managers. We chose the Neighborhood Association of São José (AMSJ), in the Municipality of Butiá, in which COPELMI Mineração Ltda. carries out socio-environmental projects, and the Beneficent Association Anjo Mineiros (ABAM), in the city of Lauro Muller, where the Carbonífera Santa Catarina Ltda has a partnership. The managers of the two community institutions were interviewed, benefiting from the actions of the respective coal companies, that characterize the RSA, related to theories of social capital.

Contemporary society has experienced local, national and international movements of concern with socio-environmental problems. Most of them are caused by man's intervention, by the possibility of ecological imbalance and the life of the planet, the problematic has gained ample space in the academic environment. This movement is noticeable in several fields of action, in the scope of education, service provision and production of consumer goods, mining, among others. At present, many organizations of medium and large size carry out and maintain social and environmental projects. Silva et al. (2011, p. 154) highlight some of the drivers of corporate strategies under SER: the evolution of environmental legislation that regulates business activities in the use of natural resources and environmental services; the greater collection of individuals in the reduction and compensation of the impacts caused by the companies in their economic activity; the pursuit of risk minimization to investors; “and by the market itself, since environmental issues have become important for the competitiveness of organizations”.

For this reason, the identification of socio- environmental practices and the reasons why companies carry them out, whether they are mandatory or voluntary, is relevant to understand the motivations of these practices in the perception of impacted agents - coal mining managers and managers of community institutions impacted by these practices, relating to social capital constituted. Philanthropy actions and direct social actions with the community are the initial dimensions that characterize CSR, as reported by Ponchirolli (2007) which can promote the development of the social capital of individuals, communities and enterprises (Table 2).

The managers’ perception about SER of the companies is directly related to the environmental management and the transparency of the actions for the good relationship with the community. “The environmental issue for us is very strong. This is one of the topics that is within our values”. This conception is evidenced in the scope of direct employees of the company: “[...]we have to be aware on this topic and show the same to the community. Mining is reputed to degrade and one of our biggest concerns is the environment issue. Not degrading is a very strong issue for us” (A1, CARB 1). The motivation for these actions is also related to the current demands of the economic market. The NBR ISO certification “is a requirement of our largest customer” (A2, CARB 1). Certified by NBR ISO 14.001 since 2005, the company is audited annually, maintaining the commitment to the continuous improvement of the Environmental Management System, “which covers the whole production complex, from the extraction of coal, through the processing, until its transport to the final customer” (CCL, 2018: 1). The same occurs with CARB 2, located in RS. According to Tachizawa and Andrade (2008), companies undergo external pressure to qualify their product, which is represented by legal certificates such as ISO 14001, which deals with the Environmental Management System (EMS) and is obtained from compliance with a set of standards that determine the environmental management guidelines of the companies.

In the environmental management policy of the two coal companies, it integrates the identification and control of environmental aspects, with minimization of the impacts associated with economic activity and the environmental recovery of the mined areas, health and safety at work, among others. The first environmental impact assessment (EIA) and its environmental impact report (RIMA) for environmental licensing in RS, developed in the company's “Butiá Leste mine” according to manager C1. With the closure of the mine and, consequently, the recovery of the mined areas, the company allows the future use of these areas. “Nowadays, in these places there are farms with soybean plantation, livestock”.

When asked about the interaction of the companies with the community to which it is inserted, the managers of the two companies CARB 1 and CARB 2 interact effectively with the community in which they are involved. The A1 manager, referring to CARB 1, stated that: “It interacts a lot, it is very active”. For the C1 manager of CARB 2, the company’s interaction occurs with all communities where it is inserted. As cited by Ponchirolli (2007), the interactions of the companies with the communities in which they are inserted are characterized in terms of the visibility of its SER. When asked about the process of interaction of the company with the community occurs, diverse situations emerged related to the promotion of projects and / or social actions in the majority. They may be representative of the constitution of the relational social capital, observed in the obligations and expectations, in social identification, cited by Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998). In CARB 1, the actions are related to the promotion and maintenance of projects and specific activities of interest to the community: lectures, environmental education, donations, among others. CARB 2, according to the manager C1, “interacts in the form of donations, trainings, lectures, community meetings, explaining mine processes. There is no monthly commitment. When the demand rises, we help”. In addition, it contributes with philanthropic punctual actions in schools, blood groups, hospital, blood bank, among others, from demand to orders. It was also noted that the scope of CARB 2 in the scope of donations is very broad.

Seeking to know more about the main actions that the companies perform in the interaction with the community, still in the analysis of the structural dimension of the social capital, we observe that all the actions and projects described in the sequence are considered relevant for the managers of the companies, among them, those impacted in the present study. The managers of CARB1, cited: Beneficent Association

Anjos Mineiros; Several Community Projects; Youth Children’s Choir

Anjos Mineiros; Home Visits; Free medical consultations; Environmental Education with lectures and campaigns of donation and planting of flowers and trees. CARB 2 invests in social and environmental actions and projects to encourage culture in search of awareness and interaction with the local community: Christmas Project Operation; Smiling for the Future Program/Community;

Project Copelmi At School; Fishing Project; Partnership with the Coal State Museum; Donations and Partnerships; Environmental Education Lectures Program.

During the interviews, significant financial investments were identified by coal producers in the various projects mentioned. Investments related to the recovery of areas degraded by mining are cited as a counterpart to mining activity and are required by national legislation. However, many projects related to corporate philanthropy are subsidized by event promotions, among others, with the direct participation of employees of the companies and communities involved. “[...]we hold a dinner party for 500 people annually, where both volunteers and we work... We always campaign for APAE, we bring “Santa Claus”, and we help with the distribution of market baskets”. (A1, CARB1)”. “[...] During Christmas, and Children's Day, we campaign among the collaborators for the donation of toys.... We work by helping some neighborhood leaders” (C1, CARB 2). Thus, we verified that the two companies develop actions related to philanthropy and social actions in the different mining units: in donation in the form of food (market baskets); milk boxes; campaigns to raise financial resources; or donation of resources in the form of work, material or financial, own, taking into account the demand of the community institutions. Bruch and Walter (2005) cite that one of the specific approaches to corporate charities relates to peripheral philanthropy. In this, charitable initiatives are usually unrelated to their main activities and are motivated mainly by external demands and stakeholder expectations.

Exemplifying one of the actions (Children’s Choir Anjos Mineiros), the A1 manager of CARB1, expresses the perception of the company's concern with the individual assistance to the project participants, “[...] If there is any child that is a component of the choir and that presents some type of problem, health or psychological, we try to give a more focused assistance to this child”. The project seeks to involve the children of the residents of the community in which most of their employees reside. They participate in rehearsals, dance festivals in the city, masses on the first Sunday of the month, etc. “[...] In these rehearsals we do recreational activities, we have meetings with snacks, we take them to day trips... We took them to Criciúma to watch a movie”.

The managers of the impacted Community institutions corroborate the perceptions of managers of coal companies; the actions and projects related to socio-environmental practices developed by the two companies are strongly related to philanthropic actions, which Ponchirolli (2007) cites as the first dimension of CSR. The main characteristic of philanthropy is the spontaneous generosity of the entrepreneur in donations to charitable and philanthropic entities. However, there are also elements of the second dimension that is related to direct social actions with the community.

Referring to CARB1, the IMP1 manager mentions that the company “[…] assists in everything we need. For example, if an outlet is defective, we turn to them. They send an electrician to take a look. Our driveway was built by them, they donated a gate”. It emphasizes the importance of these one-off actions as positive because “[...] their employees see the importance of the association and end up giving the manpower to perform these services”. Similar perception is observed in the IMP 2 manager, who claims that CARB2 is “a partner in all aspects”; citing as an example, the construction of the headquarters of the association of residents, with investment of BRL 50,000.00 from the company to assist in the construction. “The company ends up helping with its heart, because here is a very needy, very poor neighborhood... So the company is a good partner in this respect” (D1, IMP2).

We observed that, in the perception of managers, community institutions, the justification for the maintenance of these projects corroborates with the concern manifested by the managers of the companies in the execution of actions that aim at the well-being of employees and their families that are characterized in objectives of the actions. Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) say that trust is a precursor element for strengthening relations. It is a relevant aspect of observation when evaluating the relational dimension of social capital. An environment of trust contributes to the development of a high degree of trustworthiness and reliability among the subjects by inferring positive values about the behavior of the other; and therefore, is more likely to appropriate knowledge, information and other forms of resources available in their relations. According to Putnan (2003), the higher the level of trust in a community is, the greater the likelihood of cooperation. This makes it possible to boost confidence and, with this, to develop social capital.

The relationship environment and community emerged at various moments of the interviews. In both companies, there is an environmental education project with employees and third parties. Moreover, in all the events that the company CARB1 does, one approach relates to the preservation of the environment, according to the manager A1.The same is mentioned by the CARB 2 manager C1, when he emphasizes the promotion of lectures, guided visits and informative visits on the mine’s production processes and their interference in the community’s quality of life.

In the analysis of the content of the interviews we observed that the preventive actions related to the mining process in the community also occur during the process or when problems arise in residences that may be related to activity, among others. In this regard, the D1 manager of IMP 2 emphasizes the CARB 2 Company’s usefulness regarding the interference of mining activity in the community.”[...] when there problems with the houses, ..., when problems occur, their staff comes and looks, to see if it was mine that caused it. The technicians run the check. They really do help! It is a company that does not deny anything”.

The CSR actions are evidenced in the concern with the development of the municipality, one of the indicators of the motivation of the actions, where the two companies are inserted. For the A2 manager, CARB 1 “always tries to be present in the events of the municipality, to be making this move and be helping to highlight the municipality itself”. On this, the manager C1 also cites the motivation of CARB 2 related to the development of the municipality where it is inserted, when investing in the hospital, the police station, institutes and the community. As cited by Araujo (2003) factors that are not regulated exclusively by the market system, such as social, cultural and political, promote development.

In this context, there is a growing concern about the continuity of this development when the mining activity is closed. As an activity that ends with the end of the mineral reserve, communities that depend heavily on this economic activity are strongly impacted, in several aspects. According to manager C1, the company CARB2 must remain in the region with the mining activity for a maximum period of 10 years, due to the end of the mineral deposit being explored. It emerges in the manager’s speech a concern about the future of the municipality and its economic dependence on the company. In this scenario, can the social capital constituted contribute to the solution or minimization of the problem? The C1 manager of CARB2 expresses the intention of the company to assist the municipality, in the search for solutions in this scope, by promoting actions so that “the municipality has a life of its own. This is because historically the municipality was constituted with the company”.

The perception of the dependence of the community related to the company is also perceptible in the speech of the manager of IMP 2. Asked about what could happen to the residents’ association and the neighborhood after the company closes its activities in the municipality, D1 stated that: “It would certainly be a crush, for the city, the neighborhood and the entire community because it is a company, that besides contributing a lot to the city, it is a humanitarian company that cares about the neighbor, with the residents. [...]in our city today, it would be a desert”. Barbieri (2012) emphasizes that environmental responsibility is a set of individuals, collective and entrepreneurial attitudes, which aim at the sustainable development of the environment. Thus, collective strategies and actions should be planned in order to reduce the economic, social and environmental dependence of the communities by the activity carried out by a company. Likewise, social capital constituted in the community may contribute to restructuring the sectors responsible for the continuity of the region’s economic and social-environmental development, after the closure of the mining activity.

However, it was evidenced that the actions developed in the community contribute in the consolidation of mining economic activity and in the strengthening and development of the community itself, the perception of managers of coal miners and community institutions. They cite the positive way in which children and adults are currently related to mining in communities. According to the managers of CARB 1, socio-environmental actions represent a “form of motivation” for employees and indirectly generate benefits for the company. They argue, relating the satisfaction level of the employee contemplated with the actions in the community generates greater productivity “because they are geared towards improving people's lives. This contributed a lot” (A2). In addition, it is evidenced by the managers of the two coal companies that, without the socio-environmental actions, companies would have difficulty developing their activities in the region. That is, economic activity occurs because of the good acceptance of the community and the benefits granted by employees.

The evidence points to the deliberations of the investigated companies in order to develop social actions that encourage entrepreneurship. In other words, through socio-environmental projects they prefer to allocate resources to more lasting practices such as socio-cultural events, solidarity campaigns, artisanal entrepreneurship, diffusion of environmental education, professional training, waste management and incentives to plant. Although Light and Dana (2013) have identified that social capital has ceased to encourage entrepreneurship, in the cases studied there are varied actions, with significant allocations of resources to this practice.

Corporate social responsibility is also associated with regional development with the empowerment of individuals involved in the community for personal, professional and community development. Thus, a socially responsible company cares about its workers (Ponchirolli, 2007). In the two coal miners, there are active medical departments, a partial health plan, continuous training for employees related to safety in the workplace, and some specific skills for the community. There is encouragement in the academic and professional training.

In the analysis of the networks of relationships and their quality, which is one of the dimensions of social capital, the six managers said to be a friendly and sustainable? relationship, resulting from the actions developed, the regular visit to employees, the constant presence of the company in the community and society. The network of relationships built between company and community is noticeable in the many examples of actions shared between peers. The strengthening of this network of relationships is also evidenced in the concern of coal miners’ managers – who cited several examples - in keeping the motivation of the volunteers of the impacted in carrying out their activities. There was also evidence of good communication and trust between the community and the company in the managers' discourse. Citing as an example, the A1 manager of CARB1, quoted that, “When there is something different, the community usually remembers the coal company to invite. And, not only that! Sometimes we are invited to be godfathers of parties from other places”. It was observed in the content analysis that the interaction with the community where the company operates is focused on the cooperation process. However, it was not perceived the interactions related to the transfer of materials and/or technologies, training of labor, among others, cited by Ponchirolli (2007), which could impact more significantly on the personal and professional development of the community (Light and Dana, 2013).

In the respondents' response, empirical evidence is noticeable in the construction of interpersonal networks. Companies and impacted companies add the social capital of the individuals who work in it and contribute to the strengthening of their internal and external networks, through the reciprocity between them. They are based on collaboration and cooperation, responsibility for the actions developed. As these relationships are established and expanded, they can mutually generate and expand their own social capital, in new relationship networks, at different levels of performance, contributing and receiving contributions. They cite as motivation for social and environmental actions the improvement in the search for the quality of life of those involved and informal training, among others. For Putnam (1996), this collaboration is seen as an incentive to strengthen social capital, which would deepen democracy, without which it is not possible to achieve social development. It converges with evidence in other contexts, such as the study of conservation incentives can support institutions, attitudes, and social values, while rewarding environmental management (Alix-Garcia et al., 2018).

We conclude that, in the perception of managers, the main determining factors for the accomplishment of socio-environmental actions by the two coal companies investigated are associated with the good image of the companies and the development of the community where the productive units are inserted. On the other hand, through the interviews with the managers of the two community institutions, directly impacted by the socioenvironmental practices of the coal companies, we observe that, for them, the companies perform the actions like philanthropy, with the intention to help the community in which it is inserted. Therefore, there is evidence of the adherence of managerial managers in the culture of philanthropy or social actions with the community. Therefore, there is evidence of the managers’ adherence in the culture of philanthropy or social actions with the community. The actions cited by the managers characterize the company's responsibility to the community and the environment. However, even though social and environmental actions contribute to the search for solutions to socio-environmental problems, they are also punctual and isolated, requiring more in-depth reflection on effective social changes.

Evidence of Social Capital was verified based on the cooperation and reciprocity relations mentioned by the managers of the coal companies and the managers of the impacted institutions. The movements related to the philanthropy and the qualification of the subjects involved in the community aiming the personal, professional and community development, are interconnected to Corporate Social Responsibility.

In the analysis of the content of the interviews with the managers, we observed that the socio-environmental actions carried out by coal producers are philanthropic in nature and are significantly related to the personal values and beliefs of their managers. However, the present research also revealed that the actions carried out by coal producers also present strategies to improve the company’s image vis-à-vis the community, seeking a return on invested capital. In addition, the level of compromising between the coal producers and the community where they are inserted has been limited to the availability of company resources if not the need of the community. Finally, in the managers’ responses, we have identified empirical evidence of interpersonal relationship networks with reciprocity between coal companies and impacted communities, focusing on accountability, collaboration and cooperation. We have detected that the synergy among those involved, as motivation for social and environmental actions, produces improvement in the quest for quality of life and in the training of those impacted. This movement is seen as an incentive to strengthen social capital among stakeholders.

As a limitation of the study, we can observe the need to further deepen the qualitative approach, limited by the reduced availability of managers and agents impacted in the research. The second limitation was shortage and theoretical-empirical studies uniting the research constructs and combining socio-environmental practices with the local community. Finally, another aspect considered as limiting was the lack of data on socio-environmental practices carried out by coal producers in company reports.

We recommend expanding the scope of research with the participation of more carboniferous and impacted institutions in the search for validation of the effective evidence of interpersonal relationship networks, related to social and environmental actions and their inference in the development of communities.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica (ANEEL) (2008). Atlas de energia elétrica do Brasil. (3. ed.). Brasília: Aneel.

|

|

|

|

Alix-Garcia JM, Sims KR, Orozco-Olvera VH, Costica LE, Medina JDF, Monroy SR (2018). Payments for environmental services supported social capital while increasing land management. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(27):7016-7021.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Araújo LPO (2018). Carvão Mineral. Sumário Mineral 2016- DNPM-RS. In: BRASIL/DNPM. Sumário Mineral 2016. (v.36), Coord. Thiers Muniz Lima, Carlos Augusto Ramos Neves. Brasília: DNPM. pp. 38-39.

|

|

|

|

|

Araujo MCSD (2003). Capital Social (v.25). Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar.

|

|

|

|

|

Associação Brasileira de Carvão Mineral (ABCM) (2018). A História do Carvão no Brasil. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Barbieri JC (2012). Gestão ambiental empresarial: conceitos, modelos e instrumentos. (3.ed. rev.e ampl.). São Paulo: Saraiva.

|

|

|

|

|

Belolli M, Quadros J, Guidi A (2002). História do carvão de Santa Catarina. Criciúma (SC): IOESC.

|

|

|

|

|

Bourdieu P (1998). The economy of symbolic exchanges: introduction, organization and selection. San Pablo: Perspective.

|

|

|

|

|

Bourdieu P, Miceli S (1974). A economia das trocas simbólicas (p. 58). São Paulo: Perspectiva.

|

|

|

|

|

Brito AM (2006). A manifestação do capital social e da competência técnica em arranjo produtivo local (apl). (Mestrado). Programa de Pós- graduação em Tecnologia. Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná. Curitiba. Unpublished thesis.

|

|

|

|

|

Bruch H, Walter F (2005). The keys to rethinking corporate philanthropy. MIT Sloan Management Review 47(1):49-55.

|

|

|

|

|

Carbonífera Catarinense Ltda (CCL) (2018). Responsabilidade Social. Disponível em. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Carroll AB (1979). A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model Of Corporate Performance. Academy of Management Review 4(4):497-505.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Carroll AB (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business and Society 38(3):268-295.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Christoforou A (2011). Social capital across European countries: Individual and aggregate determinants of group membership. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 70(3):699-728.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cohen M, Cavazotte FSCN, Costa TM, Ferreira KCS (2017). Responsabilidade Socioambiental Corporativa como Fator de Atração e Retenção para Jovens Profissionais. In: BBR Brazilian Business Review 14(1):21-41.

|

|

|

|

|

Coleman JS (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Coleman JS (1998). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 94:S95-S120.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Coplemi Mineração Ltda (CML) (2018). Sustentabilidade. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Dabul MS (Social 2017). Responsabilidade Corporativa: Uma Discussão Teórica a partir da Nova Sociologia Econômica e da Teoria da Dádiva. (Dissertação). Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ/ IE/PPED.

|

|

|

|

|

Dias CFS, Mancin RC, Pioli MSMB (2013). Gestão para a sustentabilidade na mineração: 20 anos de história. 1.ed. Brasília: IBRAM Instituto Brasileiro de Mineração.

|

|

|

|

|

Ferrarezi E (2003). Capital social: conceitos e contribuições às políticas públicas. RSP: Revista do Serviço Público 54(4):4-20.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ferraz SFS, Gobb RL, Lima TCB (2011). Teoria do Capital Social: Um estudo no cluster moveleiro de Marco (CE). Contextus - Revista Contemporânea de Economia e Gestão 9(2):79-95.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ferrell OC, Fraedrich J, Ferrel L (2000). Ética empresarial: Dilemas, tomadas de decisões e casos. Reichmann & Affonso Ed.

|

|

|

|

|

Fukuyama F (1996). Confiança: as virtudes sociais e criação da prosperidade. Rocco.

|

|

|

|

|

Fukuyama F (2000). A grande ruptura: A natureza humana e a reconstituição da ordem social. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco.

|

|

|

|

|

Jha A, Cox J (2015). Corporate social responsibility and social capital. Journal of Banking and Finance 60:252-270.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jordana J (2000). Una nota sobre instituciones y capital social: Situando causas e efectos. Washington DC, Junio (mimeo).

|

|

|

|

|

Light I, Dana LP (2013). Boundaries of social capital in entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37(3):603-624.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Macke J (2006). Programas de Responsabilidade Social Corporativa e Capital Social: contribuições para o desenvolvimento local? 2006. Tese (Doutorado em Administração) Programa de Pós-Graduação em Administração, Escola de Administração, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre.

|

|

|

|

|

Milani C (2004). Teorias do Capital Social e Desenvolvimento Local: lições a partir da experiência de Pintadas (Bahia, Brasil). Organizações and Sociedade, 11.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review 23(2):242-266.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Onyx J, Bullen P (2000). Measuring social capital in five communities. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 36(1):23-42.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ponchirolli O (2007). Ética e responsabilidade social empresarial. Jurua Editora.

|

|

|

|

|

Portes A (1998). Social capital: It's origins and applications in contemporary society. Annual Review of Sociology 24:1-24.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Putnam R (1993). The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American prospect, 13(Spring), Vol. 4. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Putnam R (2003). El declive del capital social (No. 360 P9832d Ej. 1 018885). Círculo de lectores.

|

|

|

|

|

Putnam RD (1995). Capital social e democracia. Braudel Papers 10:175-187.

|

|

|

|

|

Santos FS (2003). Capital Social: Vários conceitos, um só problema. 2003. (Dissertação). EAESP da Fundação Getulio Vargas. São Paulo.

|

|

|

|

|

Schwartz MS, Carroll AB (2008). Integrating and unifying competing and complementary frameworks: The search for a common core in the business and society field. Business and Society 47(2):148-186.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Silva MFG (2006). Cooperation, social capital and economic performance. Brazilian Journal of Political Economy 26(3):345-363.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Silva SS, Reis RP, Amâncio R (2011). Paradigmas ambientais nos relatos de sustentabilidade de organizações do setor de energia elétrica. Revista de Administração Mackenzie 12(3):146-176.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tachizawa T (2005). Gestão ambiental e responsabilidade social corporativa: Estratégias de negócios focadas na realidade brasileira. In Gestão ambiental e responsabilidade social corporativa: Estratégias de negócios focadas na realidade Brasileira. pp. 427-427.

|

|

|

|

|

Tachizawa T, de Andrade ROB (2008). Socio-environmental management: Strategies in the new era of sustainability . Elsevier.

|

|

|

|

|

Tachizawa T, Pozo H (2017). Gestão Socioambiental: Um Modelo De Arquitetura De Sustentabilidade Empresarial. Revista de Empreendedorismo Negócios e Inovação 2(1):29-43.

|

|

|

|

|

Tachizawa T, Pozo H (2009). Gestão Socioambiental e Desenvolvimento Sustentável: um indicador para avaliar a sustentabilidade empresarial. REDE - Revista Eletrônica do PRODEMA 1(1):35-54.

|

|

|

|

|

Tinoco JEP (2000). Balanço social eo relatório da sustentabilidade. Editora Atlas SA.

|

|

|

|

|

Vallejos RV, Macke J, Olea PM, Toss E (2008). Collaborative networks and social capital: A theoretical and practical convergence. In: IFIP TC 5 WG 5.5 Ninth Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises. Poznan, Poland (Org.). Pervasive Collaborative Networks, Boston 283:3-52.

|

|

|

|

|

Witkowski A (2005). A fundação do "Sindicato dos Mineiros" de Butiá. Cadernos FAPA, Porto Alegre, n. 2, 2º sem. 2005.

|

|

|

|

|

Wu WP (2008). Dimensions of social capital and firm competitiveness improvement: The mediating role of information sharing. Journal of Management Studies 45(1):122-146.

|

|