ABSTRACT

This paper examines specific constructs for sustainable entrepreneurship as perceived in the Ugandan context using confirmatory factor analysis. This study is cross-sectional. Data were collected through a face to face survey of 384 small businesses in Kampala selected through stratified and simple random sampling. Data were analyzed through exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and descriptive statistics using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23. The study revealed that the constructs for sustainable entrepreneurship as perceived in the Ugandan context are production management, people and skills, ecosystem management, stakeholder, finance, strategy, marketing and sales. This suggests that seven factors with eigenvalues greater than one were identified, accounting for 63.23% of the total variance explained in sustainable entrepreneurship. This study presents initial evidence on the constructs of sustainable entrepreneurship that apply to the local context from the perspective of the business owners as opposed to the experts in the field. Implications on policy and practice were discussed.

Key words: Sustainable entrepreneurship, confirmatory factor analysis, Uganda.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) seek to encourage businesses across the globe to prioritize both environmental and economic growth. This has resulted in the emergence of sustainable entrepreneurship as a new field of study that allows entrepreneurs to balance the social, environmental, and economic aspects of their businesses (Shepherd and Patzelt, 2017). Accordingly, the government of Uganda is currently promoting sustainable entrepreneurship through industrialization as a catalyst for inclusive growth, employment and wealth creation in Uganda (Uganda National Planning Authority, 2020). As such, sustainable entrepreneurship is of a growing interest among academicians, practitioners, and policy makers (Muñoz and Cohen, 2018; Ploum et al., 2018; Gast et al., 2017). This is because it is estimated that about 90% of such businesses have focused on profit maximization rather than conserving the environment and societal values (Chege and Wang, 2020). This has resulted in environmental degradation, pollution, resource scarcity, and social challenges (Alani and Ezekiel, 2016; Baden and Prasad, 2016; Belz and Binder, 2017).

Extant evidence shows that most small businesses in Uganda pose both social and environmental challenges (Sendawula et al., 2020; Komakech et al., 2016). Such businesses are in the manufacturing, hotel and restaurant trade sector, for example, small businesses deal in firewood and charcoal to satisfy over 90% of Ugandans who have no access to electricity (UBOS, 2016). It is a common practice that such businesses cut trees without replacement, resulting in climate change and environmental degradation. Socially, small businesses in the agricultural sector use rudimentary technologies such as the excessive use of pesticides that pose health threats to the population (Oltramare et al., 2018).

In addressing these challenges, a new concept of sustainable entrepreneurship has emerged in entrepreneurship research. Sustainable entrepreneurship involves entrepreneurs pursuing profits while making a positive, sustainable impact on the environment and society. It also pertains to creating profitable enterprises and achieving certain environmental and social objectives; and pursuing and achieving what we often refer to as the triple bottom-line (Sarango-Lalangui et al., 2018). Scholars (Hussain et al., 2018; Sargani et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2020) have used the triple bottom line model to explain sustainable entrepreneurship. They developed it on the assumption that entrepreneurs should develop new “win-win-win” approaches. It argues that businesses should show the rapid increase of sustainable standards in their practices by balancing the three sustainability aspects. Every business whether small, medium or large has an obligation to the society in terms of economic, social or environmental aspects. To this extent, this model is relevant for this study because practicing sustainable entrepreneurship requires balancing the three sustainability aspects.

Existing sustainable entrepreneurship literature (Kimuli et al., 2020; Konys, 2019; Gast and Gundolf, 2017; Hernández-Perlines and Rung-Hoch, 2017; Mei et al., 2017; Muñoz and Dimov, 2017)has focused on its antecedents. Constructs of sustainable entrepreneurship undertaken by small businesses to maximize profits without affecting the natural environment and the values of the society remain unclear. We differ from these scholars by examining the constructs for sustainable entrepreneurship that are perceived relevant using evidence from 358 small business in Uganda. We postulate that understanding sustainable entrepreneurship constructs as perceived from the Ugandan perspective facilitates uptake of actions that have a disposable constructive effect on the environment and the society.

This paper makes several contributions to existing literature on sustainable entrepreneurship, as we used principal component analysis with varimax to extract the constructs of sustainable entrepreneurship that are more relevant in the Ugandan context. Our results show that seven constructs, namely production management, people and skills, ecosystem management, stakeholder, finance, strategy, marketing and sales, explain sustainable entrepreneurship in the Ugandan context unlike social responsibility and innovation. This suggests that seven factors with Eigen values greater than one were identified, accounting for 63.23% of the total variance explained in sustainable entrepreneurship. We based study results on the understanding and experience of the Ugandan entrepreneurs operating small business as opposed to gathering response from experts. We are confident that entrepreneurs are in a better position to offer valuable information about what is practically happening.

Triple bottom line (TBL) theory suggests the dynamic balance between its three major aspects: environmental, social, and economic dimensions. These aspects form the major dimensions of sustainability thus, the triple bottom line (Elkington, 1997). According to Elkington, TBL is a sustainability related theory with the aim to search for a better way to express sustainable actions. The theory considers three aspects in measuring business performance, practices and success of the organizations. These three aspects include; economic, social and environmental. The theory has been further developed into “3P formulation” which include; people, planet and profits (Elkington, 2006). The bottom line of businesses is profit or loss. However, in pursuit of profit, enterprises should integrate the social and environmental aspects of their operations in equal proportions. TBL also enables small business owners to take longer perspectives to evaluate future consequences of their decisions.

Many scholars have widely used the triple bottom line theory to explain sustainable development (Shepherd and Patzelt, 2017). It does not limit the use of TBL to explain sustainable development conceptually. We acknowledge that small businesses play a vital role in preserving the environment, society and attaining economic gains, and the TBL is an important concept that is enabling small businesses to do so (Muñoz-Pascual et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2018). Existent studies have adopted the TBL theory in explaining sustainable entrepreneurship (Matthews et al., 2019; Choongo et al., 2016;Shepherd and Petzelt (2017) have conducted one of the most important works on TBL to explain sustainable entrepreneurship. The authors developed a model based on the TBL aspects of the social, economic and environmental dimensions showing that entrepreneurs can operate their businesses, maximizing profits while conserving the environment and the values of the society.

The economic aspect deals with the flow of money in and out of the business (Rossi et al., 2020). Entrepreneurs are not doing charity work; they cannot survive without financial resources hence for sustainable entrepreneurs to operate successfully, they need to balance financial, social and environmental aspects. Entrepreneurs who heavily emphasize economic gains are known as conventional or commercial entrepreneurs (Das and Rangarajan, 2020). This implies that such economic entrepreneurs exploit opportunity and use resources for profit gains and therefore are not sustainable entrepreneurs since their primary goal is economic gains. The economic line of TBL refers to the business practices that impact on the economic system (Arsi? et al., 2020; Elkington, 2004). In addition, it refers to the ability of the economy as the sub-system of sustainability to continue in order to support future generations (Niaki et al., 2019). It focuses on the economic value in terms of consistent economic growth, risk management, saving, research and development, wages, taxes and employment. Thus, small business owners in Uganda undertake entrepreneurial actions purposely to maximize profits. This implies that the majority of them are seemingly not sustainable entrepreneurs. Therefore, this study sought to investigate sustainable entrepreneurship constructs as perceived in the Ugandan context.

Businesses are globally responsible to contribute to social development through job creations and tax payment to the government. However, businesses have currently changed their attitude toward social responsibility of the business because of emergence of corporate social responsibility that is like sustainable entrepreneurship. Gupta et al. (2020) revealed that a sustainable entrepreneur is one who fulfills people and community needs. Thus, the social line of the TBL refers to business practices that benefit the community or society (Elkington, 1997). These practices should value the society by considering the community in pursuit of profits. Such practices include; employment, education, social care, health, community investment, recreation, cultural investment and public awareness. Leaving out the social aspect may lead to increased economic costs in terms of security and market share (Sahasranamam and Nandakumar, 2020). It is important to note that social entrepreneurship and sustainable entrepreneurship are different. This is because both concepts have different agendas. For example, social entrepreneurs focus on social aim, welfare, and unity. On the other hand, sustainable entrepreneurship should not focus on social aspects only but balancing the economic, environmental and social aspects in equal proportions. Therefore, small business owners in Uganda should practice sustainable entrepreneurship through undertaking activities that improve the welfare of the society while making profit and conserving the environment.

The environmental aspect is the most widely recognized dimension of sustainable entrepreneurship in literature.Shepherd and Patzelt (2017)acknowledged that the ecological system is the foundation of environmental sustainability because resources such as air, water and energy are part of the environment. Such resources are scarce and non-renewable; thus, they should be preserved to benefit the current and future generations. Therefore, the environmental aspect in TBL refers to engaging in practices that do not compromise the environmental resources for future generations (Elkington, 1997). It pertains to the efficient use of energy resources, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and minimizing the ecological footprint (Sun et al., 2020; Adedoyin et al., 2020). Hence, small business owners-managers in Uganda should undertake entrepreneurial actions that are preserving natural resources for the benefit of the current and future generations.

Concept of sustainable entrepreneurship

Sustainability comes from sustainable development, which simply means development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Brundtland, 1987). Scholars have defined sustainability differently, with complicated meanings and interpretations. According to Purvis et al. (2019), sustainability is a rise in the standards of living of the poor in terms of food, access to education, healthcare, water and actual income. In addition, Salas?Zapata and Ortiz?Muñoz (2019) view sustainability as the capacity to stand for a period of time. Furthermore, Elkington (1994)defines sustainability as the balancing of the environment, social and economic aspects. This is also known as the triple bottom line (TBL). John Elkington coined triple bottom line in 1994. Triple bottom line has been the emphasis of sustainability in business. In another study, they extended triple bottom line to include five domains; economic, social, ecological, cultural and ethical aspects (Nuringsih et al., 2019). The impact of the triple bottom line is viewed in terms of “Economic (break-even point), self-defined social and self-defined ecological value-creation goal reached” (Farny and Binder, 2021). We conclude the sustainable entrepreneurship journey with attaining financial breakeven point and the enterprise’s own social and environmental goals.

In recent times, the United Nations has come up with sustainable development goals that include; ending poverty and hunger, improving health and education, making cities more sustainable, combating climate change and protecting oceans and forest (

Leal, 2020). These goals require entrepreneurs to go out in search of opportunities to create value while keeping in mind sustainable use of resources. Entrepreneurship is an important conduit for a more sustainable economy. Entrepreneurs pass on sustainable products, process, and start-ups in order to solve social and environmental problems (Belz and Binder, 2017). This kind of process has been termed as sustainable entrepreneurship (Shepherd and Patzelt, 2017).

Sustainable entrepreneurship is a new concept of the entrepreneurship literature that has no consensus on the definition. All the definitions have emphasis on five aspects like its process, a goal, source of entrepreneurial opportunities, to whom, balancing TBL, transition of future goods and services, recognition, developing and exploiting opportunities (Binder and Belz, 2015). In addition, Sustainable entrepreneurship is defined as “the focus on the preservation of nature, life support, and community in pursuing perceived opportunities to bring into existence future products, processes, and services for gain, where gain is broadly construed to include economic and non-economic gains to individuals, the economy, and the society” (Shepherd and Patzelt, 2017).

In this study, we view sustainable entrepreneurship as a concept that endeavors to balance the economic, social and environmental aspects. In other words, they should pursue economic gains while keeping the environmental and social impact at the minimum. Sustainable entrepreneurship research is still in its infancy stage with so many conceptual studies. Quantitative and empirical studies are still few. Therefore, there is a need to examine specific constructs for sustainable entrepreneurship as perceived in the Ugandan context using confirmatory factor analysis.

We should pursue sustainable entrepreneurship with the growing benefits. Small business owners could use it as a competitive advantage in terms of reputation, customer satisfaction, organizational commitment, financial performance, motivation of employees, risk management, market opportunities and improvement in internal business dynamics (Cantele and Zardini, 2018; Alani and Ezekiel, 2016). However, taking on sustainability is costly for entrepreneurs in the short term though with multiple benefits in the long term (Kimanzi and Gamede, 2020).

In addition, social and environmental problems have created potential business opportunities which entrepreneurs can exploit, thereby balancing the social, economic and environmental aspects of their businesses to benefit the stakeholders (Belz and Binder, 2017). As such, sustainable entrepreneurship may attract funding from the public, which suggests that sustainable enterprises have a better market position. Though the market is top end and most often not available, it is tedious which increases the chances of failure. Other scholars like Soto-Acosta et al. (2016)found out that sustainable entrepreneurship influences long term business performance in terms of sustainability and may lead to market share growth of the firm.

Previous studies have focused on competences, institutional framework, risks and barriers, entrepreneurial environment, altruism towards others, knowledge, government regulations, sustainable entrepreneurship practices, value and future orientation of sustainable entrepreneurs (Alani and Ezekiel, 2016; Fichter and Tiemann, 2018; Hoogendoorn et al., 2019; Ahmad et al., 2020; Thelken and de Jong, 2020), with less attention on the dimensions of sustainable entrepreneurship. This motivated the researchers to conduct this study to examine the specific dimensions of sustainable entrepreneurship as perceived in the Uganda context using evidence from small businesses.

The study's research design was cross-sectional and correlational. The study population is made up of 108,534 small businesses in Kampala (UBOS, 2016). Using Krejcie and Morgan (1970) sampling table, 384 small businesses were selected. We selected small firms from the trade, hospitality and manufacturing business sectors using stratified and simple random sampling techniques. We categorized small businesses according to the number of employees and capital investment (MTIC, 2015). Accordingly, businesses that employ between 5 and 49 and have a capital investment of UGX: 10 million but not more than 100 million were included in this study (MTIC, 2015). Out of the targeted sample size of 384 small businesses, we received 358 usable questionnaires back from small business owners who completed the questionnaires, giving a response rate of 93%. The researcher's face-to-face engagement with the respondents and maintaining of frequent communication with respondents during the data collection process resulted in the high response rate. We chose small businesses as the unit of research for this study because they contribute significantly to the growth of the Ugandan economy by creating jobs, distributing wages, and generating government revenue (Orobia et al., 2020). We chose small business owners or managers as the unit of inquiry because they possess pertinent knowledge about the businesses under investigation.

A questionnaire using six-point Likert scale ranging from Very often to Never was designed and used to collect the data by measuring the opinions of respondents. We used a face-to-face administration of questionnaire to enable interaction between the researcher and the respondents, and to improve the quality of responses and response rate. The questionnaire design was based on reviewing extant literature on sustainable entrepreneurship (Shepherd and Patzelt, 2017). Sustainable entrepreneurship was measured using Soto-Acosta et al. (2016) and Elkington (1997) items that include; environmental sustainability (ecosystem management, production management, resource management), social sustainability (social responsibility, people and skills, stakeholders) and economic sustainability (strategy, finance, marketing, innovation).

We use factor analysis, Cronbach's alpha coefficient, and content validity index to test for the validity and reliability of the research instrument. The content validity index (CVI) was computed and had a CVI value of 0.80. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was measured to test reliability of how closely related a set of items are as group and the Cronbach alpha values for all the study variables were above 0.7 which is acceptable (Nunnally, 1967).

Data analysis

SPSS was used to summarize the data and facilitate the analysis of the findings. Specifically, quantitative data derived from the questionnaire was analyzed using data coding to get exploratory factor analysis results in order to classify components of sustainable entrepreneurship as viewed by Ugandans (Field, 2013). Additionally, frequencies were developed to document the many activities that exemplify sustainable entrepreneurship in small businesses. This was followed by a confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS to validate the constructs of sustainable entrepreneurship using data from Uganda's small businesses (Hair et al., 2014).

The study revealed that majority of the respondents were females (52%), and the majority were in the 29-39 years age bracket (38%), followed by those in the 18-28 years age group (28%), clearly showing that on average, those in business are below 40 years old. In addition, majority of the respondents had either a diploma or bachelor’s degree (27%), showing that they have enough knowledge to take part in the study. This is followed by masters’ degree holders (20%), showing that the respondents were knowledgeable as far as the issues under study are concerned. However, majority of the small business owners and managers had got training on sustainability concerns (53%) while 47% had no form of training on sustainability concerns. The results further show that most of the businesses were between 2-5 years old (55%). This is followed by those that have been around for a period between 6-10 years (30%), showing that most of the businesses were fairly new in their operations.

The purpose of this study was to examine sustainable entrepreneurship construct in order to identify its components as perceived in the Ugandan context. This section starts with exploratory factory analysis results, followed by descriptive statistics using frequencies.

A principal component analysis (PCA) was utilised to reduce the number of variables under investigation and highlight groups of interrelated variables. All the assumptions of the PCA model were satisfied as suggested by Field (2013). Table 1 shows that seven factors with Eigen values greater than one were identified, accounting for 63.23% of the total variance explained in sustainable entrepreneurship.

Except for items under resource management and strategy, each variable had its highest loadings (above 0.5) on the component it conceptually belongs to showing convergent validity is adequate. Reliability tests relating to each component scale were satisfactory, with reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.07 or higher. Seven items were extracted as opposed to the ten conceptualised factors. It eliminated all items under social responsibility and innovation, while all items under resource management loaded on the production management construct. The seven factors were labelled as production management, people and skills, ecosystem management, stakeholder, finance, strategy and marketing, respectively. Furthermore, it was established that production management explained more of the variance in sustainable entrepreneurship (12.5%), followed by people and skills (11.8%), ecosystem management (10.7%), stakeholder (8.9%), finance (7.9%), strategy (6.6%) and marketing (4.9%) respectively. This implies that production management more than the other factors causes variability in sustainable entrepreneurship.

Further analyses were conducted to establish the frequency of undertaking the various activities that reflect sustainable entrepreneurship among small businesses, and we report the results for each construct of sustainable entrepreneurship in the following section.

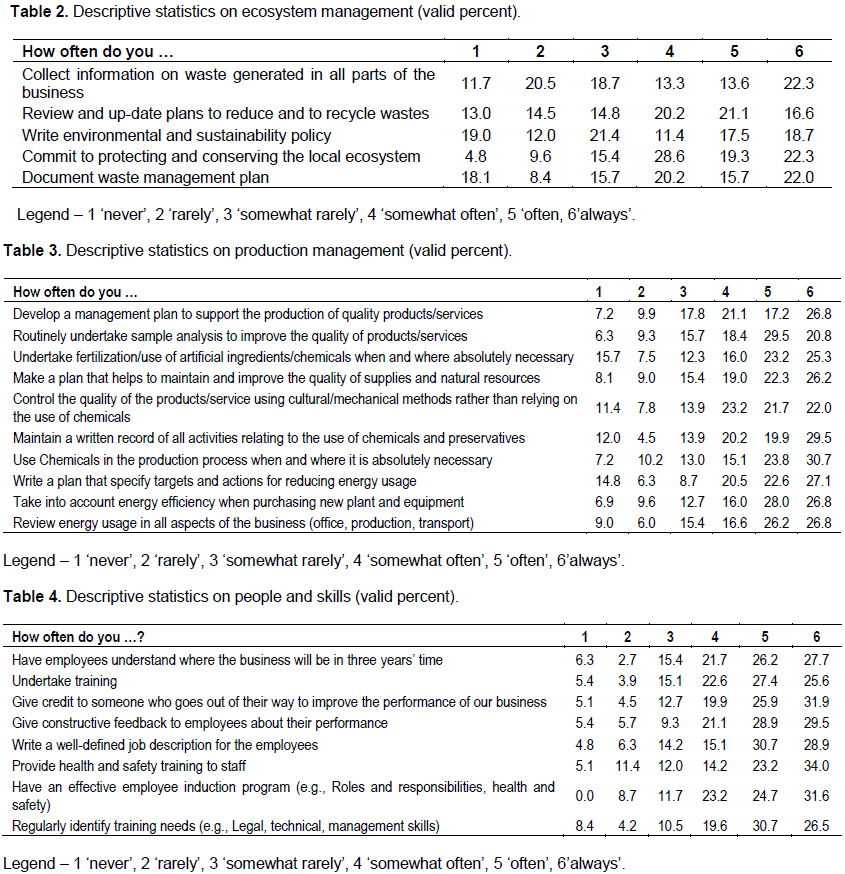

Frequency distribution on ecosystem management

Results in Table 2 show that on average, the identified activities under ecosystem management are often undertaken by the small businesses, thus reflecting evidence of sustainable entrepreneurship.

Frequency distribution on ecosystem management

Results in Table 2 show that on average, the identified activities under ecosystem management are often undertaken by the small businesses, thus reflecting evidence of sustainable entrepreneurship.

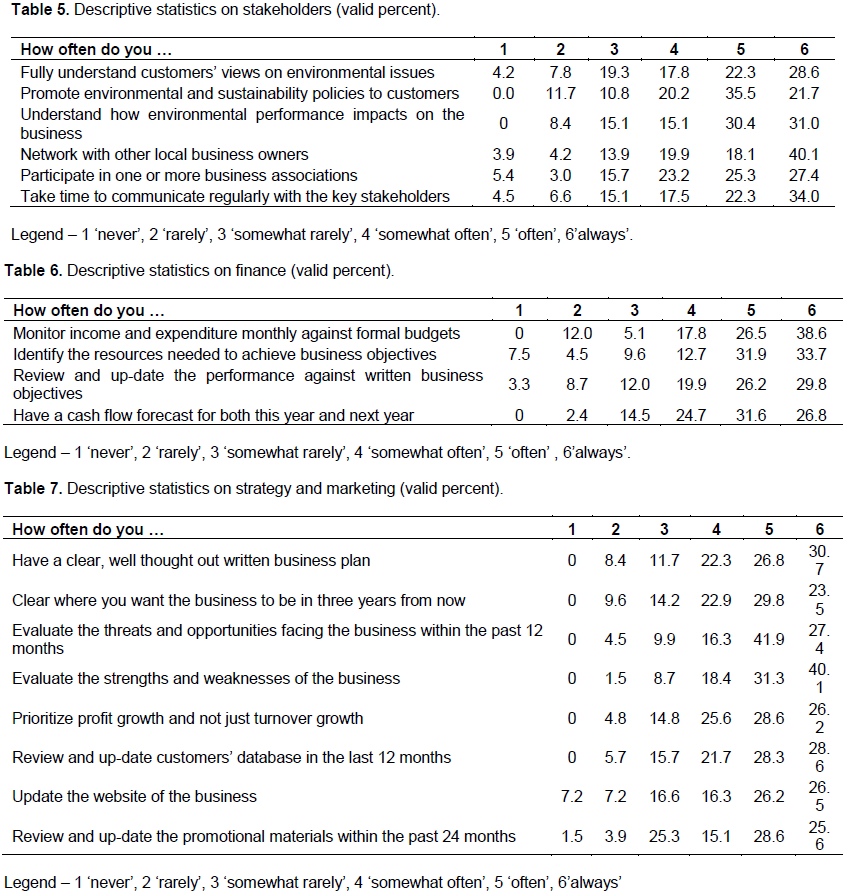

Frequency distribution on production management

Results in Table 3 show that on average, the identified activities under production management are often undertaken by the small businesses, thus reflecting evidence of sustainable entrepreneurship.

Frequency distribution on people and skills

Results in Table 4 show that on average, the identified activities under people and skills are often undertaken by the small businesses, thus reflecting evidence of sustainable entrepreneurship.

Frequency distribution on stakeholders

Results in Table 5 show that on average, the identified activities under stakeholders are often undertaken by the small businesses, thus reflecting evidence of sustainable entrepreneurship.

Frequency distribution on finance

Results in Table 6 show that on average, the identified activities under finance are often undertaken by the small businesses, thus reflecting evidence of sustainable entrepreneurship.

Frequency distribution on strategy and marketing

Results in Table 7 show that on average, the identified activities under two constructs–strategies and marketing are often undertaken by the small businesses, thus reflecting evidence of sustainable entrepreneurship.

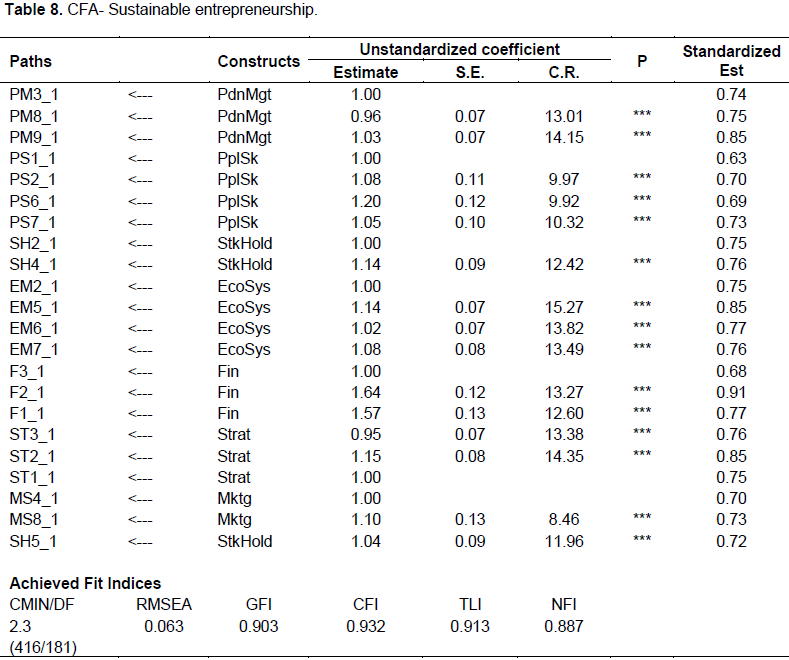

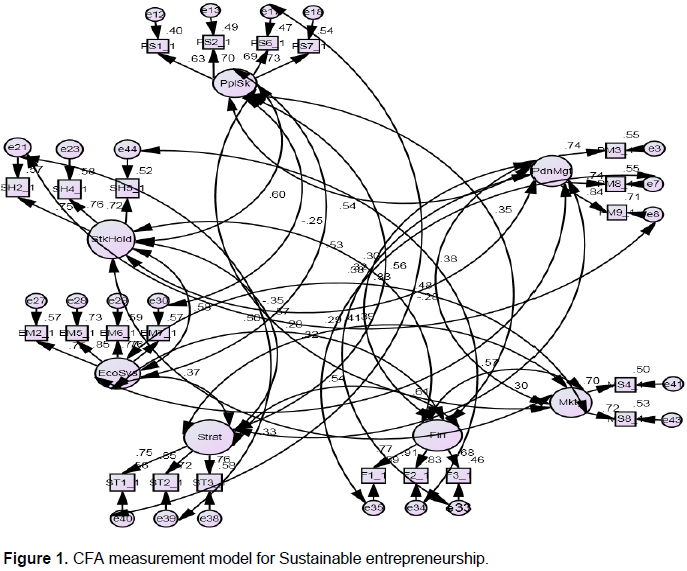

CFA measurement model for sustainable entrepreneurship

We measured sustainability entrepreneurship using environmental sustainability, social sustainability and economic sustainability. Nonetheless, environmental sustainability was measured in terms of ecosystem management, production management and resource management; we measured social sustainability in terms of social responsibility, people and skills and stakeholders; while we measured economic sustainability in terms of strategy, finance, marketing and sales and innovation, resulting in 10 factors. However, these factors were reduced to 7 factors during the EFA and subjected to a CFA. The initial CFA results showed that although the standardized parameter estimates were all significant (p<0.001), the fit-indices were below the acceptable level signifying a poor measurement model fit. This caused a re-specification by iteratively removing items that did not meet the acceptable criteria. The purpose of repeating the filtering process was to remove as few items as possible, considering the need to derive a more parsimonious model. Examination of the modification indices (MIs) revealed mis-specifications affiliated with 22 items. 22 out of 44 items in total were iteratively removed in the ultimate model prior to further analysis. While the number of deleted items was relatively high compared to the total, their removal did not change the content of the construct as it was conceptualized. This is so because the retained items were significant and had standardized factor loadings higher than the recommended level of 0.50 thus, the meanings of the factors were preserved. The findings confirmed the validity of the ultimate model with excellent model fit statistics for this construct measure as reported in Table 8 and Figure 1. Given that the model fit the data well and the correlation between the underlying factors was less than 0.85, no further adjustments were required.

The study results show that seven constructs that include; production management, people and skills, ecosystem management, stakeholder, finance, strategy, marketing and sales explain sustainable entrepreneurship in the Ugandan context. This suggests that seven factors with Eigen values greater than one were identified, accounting for 63.23% of the total variance explained in sustainable entrepreneurship.

Firstly, looking at the exploratory factor analysis results, it was established that seven factors that make up sustainable entrepreneurship were extracted, as opposed to the ten factors fronted by the triple bottom line scholars. Specifically, all items under social responsibility and innovation were eliminated, while all items under resource management loaded on the production management construct. The seven factors were labeled as production management, people and skills, ecosystem management, stakeholder, finance, strategy and marketing, respectively. Environment sustainability remained with ecosystem and production management, Social sustainability remained with people and skills and stakeholders, while financial sustainability remained with finance, strategy and marketing. This has implications for future studies on sustainable entrepreneurship in Uganda, in that such factors should employ the seven factors and not necessarily the original ten factors. Social responsibility items may not measure sustainable entrepreneurship in Uganda because, the profit margin of these businesses does not permit them to undertake such activities as compared to big companies that have enough resources to support social activities as one of the marketing strategies. As such, small businesses rarely engage in social responsibility activities, except for helping the traditional extended families. The elimination of innovation as a factor of sustainable entrepreneurship can be explained by the fact that most businesses in Uganda are the “me-too” businesses. The copy-cat syndrome does not provide room for development of new ideas, products and processes. Basing on these arguments, social responsibility and innovation are inconsequential in constructing sustainable entrepreneurship among small businesses in Uganda.

These results are consistent with Soto-Acosta et al. (2016), who reported that business owners’ approaches towards the social, environmental and economic aspects promote businesses performance in terms of increased turnover and market share and customer satisfaction and retention. This is further echoed by Hosseininia and Ramezani (2016). They showed that social and environmental factors of customer orientation, recycling, and the need to conserve the future significantly promotes sustainable entrepreneurship of SMEs in Iran's food industry. However, our results disagree with Mayanja et al. (2019), who reported that there is a positive relationship between entrepreneurial networking and ecologies of innovation of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Uganda. This suggests that SMEs innovate their products, services, markets and operations to meet the changing customer needs.

Secondly, it was evident that environmental sustainability explains more variance (23.3%) in sustainable entrepreneurship followed by social sustainability (20.7%) and economic sustainability (19.4%) respectively. When investigating sustainable entrepreneurship among small businesses, emphasis should be put on environment and social factors than economic factors. No wonder, it is frequently reported that such businesses rarely survive beyond three years because they lack the financial muscle which is the oxygen of any business as blood is for humans. This deduction resonates well with Namagembe et al. (2019). They reported that eco-design and internal environmental management practices positively and significantly influence the ecological performance of manufacturing small and medium enterprises in Uganda. Li et al. (2020) also add that industries exhibit clean production behaviour and green supply chain management practice. This implies that businesses that undertake their production and supply chain operations while considering the natural environment usually supports the uptake of environmental sustainability practices in their operations. In another study conducted by Piyathanavong et al. (2019) on adopting organizational environmental protection methods in Thailand's manufacturing sector, it was revealed that manufacturing firms consider the impact on the environment and benefits from adopting these operational approaches as the company's policy and initiative, environmental awareness, and cost saving as the primary reasons for adopting environmental sustainability practices in Thailand.

Thirdly, the descriptive statistics revealed that respondents were regularly involved in activities related to economic, social and environment sustainability. On the face, the results seem to contradict the earlier motivation of the study. Nonetheless, a deeper analysis revealed that most of these actions are done in a rudimentary manner. For instance, most small businesses do not have well prepared plans let alone strategic plans. But they have something sketchy which often is kept as ‘memory records’. On training employees and creating awareness to customers about sustainability matters, they do so subconsciously without forethought. They do not have written policies to this effect. In addition, most of the businesses have waste disposal mechanisms in place to ensure that they try not to litter their waste. In a nutshell, these activities are undertaken in a rudimentary way and when compared to formal procedures, such activities would pass as non-existent. This is supported by the findings of Orobia et al. (2020) that revealed that youth and women entrepreneurs undertake social, environmental and economic practices in their businesses. This is further strengthened by Sendawula et al. (2020), who showed that manufacturing small and medium enterprises undertake waste management, eco-friendly packaging, energy efficiency and water conservation as practices that have to conserve the natural environment and the values of the society while catalyzing economic development.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study has shown that sustainable entrepreneurship in small businesses is best understood from the lens of the small business owners. On understanding sustainable entrepreneurship among small businesses in Uganda, the study revealed that there is evidence of practice of economic, environmental and social sustainability thus sustainable entrepreneurship. This finding was not surprising because Uganda is a collectivist economy and therefore sustainability issues are a major concern to most citizens. In Uganda, all businesses, customers and other stakeholders in the society jointly used certain resources, for example, free education at the primary and secondary levels and roads are used freely. In addition, Uganda faces many social problems such as poverty, unemployment, prostitution, corruption, crimes, poor health, drug abuse, child labour and poor education facilities. This implies that social sustainability comes at the forefront. Similarly, environmental concerns like pollution, deforestation are a major call by Ugandans of recent.

Our findings imply that policymakers should develop and closely monitor production management, people and skills, ecosystem management, stakeholder, finance, strategy, marketing and sales aspects of small businesses if sustainable entrepreneurship is to be embraced in Uganda. Small-business owner-managers should also integrate the social, environmental and economic aspects in their businesses to catalyze sustainable development in Uganda.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adedoyin FF, Alola AA, Bekun FV (2020). An assessment of environmental sustainability corridor: the role of economic expansion and research and development in EU countries. Science of the Total Environment 713:136726.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ahmad NH, Rahman SA, Rajendran NLKA, Halim HA (2020). Sustainable entrepreneurship practices in Malaysian manufacturing SMEs: the role of individual, organisational and institutional factors. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 16(2):153-171.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Alani F, Ezekiel O (2016). Critical Success Factors for Sustainable Entrepreneurship in SMEs: Nigerian Perspective. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing 7(3):2039-9340.

|

|

|

|

|

Arsi? M, Jovanovi? Z, Tomi? R, Tomovi? N, Arsi? S, Bodolo I (2020). Impact of logistics capacity on economic sustainability of SMEs. Sustainability 12(5):911.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Baden D, Prasad S (2016). Applying behavioural theory to the challenge of sustainable development: Using hairdressers as diffusers of more sustainable hair-care practices. Journal of Business Ethics 133(2):335-349.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Belz FM, Binder JK (2017). Sustainable entrepreneurship: A convergent process model. Business Strategy and the Environment 26(1):1-17.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Binder JK, Belz FM (2017). Developing Sustainable Opportunities: Merging Insights from Social Identity and Structuration Theory. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2017, No. 1, p. 14167). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Binder JK, Belz FM (2015). Sustainable entrepreneurship: what it is. In Kyrö P (ed.): Handbook of entrepreneurship and sustainable development research pp. 30-75.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Brundtland GH (1987). World Commission on Environment and Development: our Common Future, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

|

|

|

|

|

Cantele S, Zardini A (2018). Is sustainability a competitive advantage for small businesses? An empirical analysis of possible mediators in the sustainability-financial performance relationship. Journal of Cleaner Production 182:166-176.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chege SM, Wang D (2020). The impact of entrepreneurs' environmental analysis strategy on organizational performance. Journal of Rural Studies 77:113-125.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Choongo P, Van Burg E, Paas LJ, Masurel E (2016). Factors influencing the identification of sustainable opportunities by SMEs: Empirical evidence from Zambia. Sustainability (Switzerland) 8(1):1-24.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Das M, Rangarajan K (2020). Impact of policy initiatives and collaborative synergy on sustainability and business growth of Indian SMEs. Indian Growth and Development Review 13(3):607-627.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Elkington J (2004). Enter the triple bottom line. The triple bottom line: Does it all add up 11(12):1-16.

|

|

|

|

|

Elkington J (1994). Towards the sustainable corporation: win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. California Management Review 36:90-100.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Elkington J (1997). Partnerships from Cannibals with Forks?: The Triple Bottom line of 21st Century Business. Environmental Quality Management 199:37-51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Elkington J (2006). Governance for Sustainability. Corporate Governance. An International Review 14(6):522-529.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Farny S, Binder J (2021). Sustainable entrepreneurship. In World Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fichter K, Tiemann I (2018). Factors influencing university support for sustainable entrepreneurship: Insights from explorative case studies. Journal of Cleaner Production 175:512-524.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Field A (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics, Statistic.

|

|

|

|

|

Gast J, Gundolf K (2017). Doing business in a green way?: A systematic review of the ecological sustainability entrepreneurship literature and future research. Journal of Cleaner Production 147:44-56.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gast J, Gundolf K, Cesinger B (2017). Doing business in a green way: A systematic review of the ecological sustainability entrepreneurship literature and future research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production 147:44-56.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gu W, Wang J, Hua X, Liu Z (2020). Entrepreneurship and high-quality economic development: based on the triple bottom line of sustainable development. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 17(1):1-27.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gupta P, Chauhan S, Paul J, Jaiswal MP (2020). Social entrepreneurship research: A review and future research agenda. Journal of Business Research 113:209-229.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hair JF, Gabriel M, Patel V (2014). AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Brazilian Journal of Marketing 13(2):44-45.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hernández-Perlines F, Rung-Hoch N (2017). Sustainable entrepreneurial orientation in family firms. Sustainability (Switzerland) 9(7):1-16.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hoogendoorn B, Van der Zwan P, Thurik R (2019). Sustainable entrepreneurship: The role of perceived barriers and risk. Journal of Business Ethics 157(4):1133-1154.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hosseininia G, Ramezani A (2016). Factors influencing sustainable entrepreneurship in small and medium-sized enterprises in Iran: A case study of food industry. Sustainability 8(10):1010.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hussain N, Rigoni U, Orij RP (2018). Corporate governance and sustainability performance: Analysis of triple bottom line performance. Journal of Business Ethics 149(2):411-432.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kimanzi MK, Gamede VW (2020). Embracing the role of finance in sustainability for SMEs. International Journal of Economics and Finance 12(2):453-468.

|

|

|

|

|

Kimuli SNL, Orobia L, Sabi HM, Tsuma CK (2020). Sustainability intention: mediator of sustainability behavioral control and sustainable entrepreneurship. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 16(2):81-95.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Komakech AJ, Zurbrügg C, Miito GJ, Wanyama J, Vinnerås B (2016). Environmental impact from vermicomposting of organic waste in Kampala, Uganda: Journal of Environmental Management 181:395-402.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Konys A (2019). Towards sustainable entrepreneurship holistic construct. Sustainability 11(23):6749.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Krejcie RV, Morgan DW (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement 30:607-610.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Leal FW (2020). Viewpoint: accelerating the implementation of the SDGs. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 21(3):507-511.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Li X, Du J, Long H (2020). Understanding the green development behavior and performance of industrial enterprises (GDBP-IE): scale development and validation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(5):1716.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Liang X, Zhao X, Wang M, Li Z (2018). Small and medium-sized enterprises sustainable supply chain financing decision based on triple bottom line theory. Sustainability 10(11):4242.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Matthews RL, Tse YK, O'Meara Wallis M, Marzec PE (2019). A stakeholder perspective on process improvement behaviours: delivering the triple bottom line in SMEs. Production Planning and Control 30(5-6):437-447.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mayanja S, Ntayi JM, Munene JC, Kagaari JRK, Waswa B (2019). Ecologies of innovation among small and medium enterprises in Uganda as a mediator of entrepreneurial networking and opportunity exploitation. Cogent Business and Management 6(1):1641256.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mei H, Ma Z, Jiao S, Chen X, Lv X, Zhan Z (2017). The sustainable personality in entrepreneurship: The relationship between Big Six personality, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention in the Chinese context. Sustainability (Switzerland) 9(9):5-8.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

MTIC (2015). Uganda Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise (MSME) policy.

|

|

|

|

|

Muñoz P, Cohen B (2018). Sustainable entrepreneurship research: Taking stock and looking ahead. Business Strategy and the Environment 27(3):300-322.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Muñoz P, Dimov D (2017). Moral intensity as catalyst for opportunities for sustainable development. In: The world scientific reference on entrepreneurship. Sustainability, Ethics, and Entrepreneurship 3:225-247.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Muñoz-Pascual L, Curado C, Galende J (2019). The triple bottom line on sustainable product innovation performance in SMEs: A mixed methods approach. Sustainability 11(6):1689.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Namagembe S, Ryan S, Sridharan R (2019). Green supply chain practice adoption and firm performance: manufacturing SMEs in Uganda. Management of Environmental Quality 30(1):5-35.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Niaki MK, Torabi SA, Nonino F (2019). Why manufacturers adopt additive manufacturing technologies: The role of sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 222:381-392.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nunnally JC (1967). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

|

|

|

|

|

Nuringsih K, Nuryasman MN, IwanPrasodjo RA (2019). Sustainable entrepreneurial intention: The perceived of triple bottom line among female students. Journal of Management 23(2):168-190.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Oltramare C, Weiss FT, Atuhaire A, Staudacher P (2018). Impact of pesticide use by smallholder farmers on water quality in the Wakiso District: Uganda. EGU General Assembly 19, 19228.

|

|

|

|

|

Orobia AL, Tusiime I, Mwesigwa R, Ssekiziyivu B (2020). Entrepreneurial framework conditions and business sustainability among the youth and women entrepreneurs. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 14(1):60-75.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Piyathanavong V, Garza-Reyes JA, Kumar V, Maldonado-Guzmán G, Mangla SK (2019). The adoption of operational environmental sustainability approaches in the Thai manufacturing sector. Journal of Cleaner Production 220:507-528.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ploum L, Blok V, Lans T, Omta O (2018). Toward a validated competence framework for sustainable entrepreneurship. Organization and environment 31(2):113-132.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Purvis B, Mao Y, Robinson D (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Science 14(3):681-695.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rossi E, Bertassini AC, dos Santos Ferreira C, do Amaral WAN, Ometto AR (2020). Circular economy indicators for organizations considering sustainability and business models: Plastic, textile and electro-electronic cases. Journal of Cleaner Production 247:119137.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sahasranamam S, Nandakumar MK (2020). Individual capital and social entrepreneurship: Role of formal institutions. Journal of Business Research 107:104-117.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Salas?Zapata WA, Ortiz?Muñoz SM (2019). Analysis of meanings of the concept of sustainability. Sustainable Development 27(1):153-161.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sarango-Lalangui P, Santos JLS, Hormiga E (2018). The development of sustainable entrepreneurship research field. Sustainability 10(6):2005.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sargani GR, Zhou D, Raza MH, Wei Y (2020). Sustainable entrepreneurship in the agriculture sector: The nexus of the triple bottom line measurement approach. Sustainability 12(8):3275.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sendawula K, Bagire V, Mbidde CI, Turyakira P (2020). Environmental commitment and environmental sustainability practices of manufacturing small and medium enterprises in Uganda. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shepherd DA, Patzelt H (2017). Researching entrepreneurships' role in sustainable development. In Trailblazing in Entrepreneurship: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. pp. 149-179.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Soto-Acosta P, Cismaru DM, V?t?m?nescu EM, Ciochin? R (2016). Sustainable Entrepreneurship in SMEs: A Business Performance Perspective. Sustainability 8(4):342.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sun H, Mohsin M, Alharthi M, Abbas Q (2020). Measuring environmental sustainability performance of South Asia. Journal of Cleaner Production 251:119519.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Thelken HN, de Jong G (2020). The impact of values and future orientation on intention formation within sustainable entrepreneurship. Journal of Cleaner Production 266:122052.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) (2016). Statistical abstract. In Uganda Bureau of Statistics Statistics.

|

|

|

|

|

Uganda National Planning Authority (2020). Third national development plan (NDPIII) 2020/21 - 2024/25.

|

|