In spite of the evidence that African Women under the post-World War I economy were subjected to brutal exploitation and underdevelopment as much as their male counterparts, Women Studies has remained a neglected theme in the historiography of post-World War I Africa. In fact, Nigeria’s Benin economic and development history typifies and reflects this reality of neglect across all its historical epochs. This study examines the conceptualization and practice of development and its impact on African women, with specific reference to the growth in the oil palm industry in Nigeria’s Benin Province between 1914 and 1938. It finds that African women were a major target of a systematic colonial exploitation under the post-World War I economy. It concludes therefore that the colonizer’s notion and practice of development was one at variance with the development of the African women in the industry. Rather, it, by all intent and purposes, facilitated the development of Britain while under-developing African women in spite of the growth and expansion of the export oil palm industry in Nigeria’s Benin Province.

Women constitute more than half the population of Nigeria, Africa’s most populated country. Yet, they are presumed to be less favoured in the socio-economic equation in post-independence Nigeria. Though statistics are porous, it is believed that Nigerian women, like most other African women, bare a higher share of the burdens of poverty, unemployment, illiteracy and disease. The affirmative action of the regime of Dr. Goodluck Jonathan in allocating to and appointing women into thirty-five percent of public positions between 2011 and 2015, we reason in this study, is a tacit official acknowledgement of the inequalities that exist in the development of women and men in many spheres of life in the contemporary African societies. The African women in Nigeria are, therefore, ranked lower on the ladder of development than their male counter parts in terms of access to public goods.

Since material wellbeing is not unconnected with one’s role and place in society, the lack of the development of African women vis-à-vis their male counterparts is assumed to be connected with their socio-economic exclusion and political marginalization. This degeneration of the fortunes of African women on the hierarchy of development would appear to have been rooted in the conception and practice of development that defined the structure of the post-World War I (1914 to 1938) colonial economy in Nigeria.

This study, therefore, argues the thesis that growth in the oil palm industry did not bring about the development of the African women in Benin Province, but does, however, agree that the exploitation and under-development of the women were motivated and perpetuated by the network of social relations of production between men and women. It perceives the exploitation and under-development of the women through the lens of the capitalist social relations of production that predominated under the colonial economy of the post-World War I era. It thus examines the contributions of women to the development of the colonial economy with specific reference to the oil palm industry in Benin Province within the praxis of the classical economic and development theory operative in the post-WW I British colony of Nigeria. To this end, the study attempts to answer the following questions.

1. What was the role and place of African women in the oil palm economy prior to colonization?

2. What role did African women play in the development of the post-WW I oil palm industry in Nigeria’s Benin Province?

3. To what extent did the role of African women in the export oil palm industry in Benin Province change under the post-WW I colonial economy?

4. What were the impacts of the changing role of African women in the post-WW I colonial economy?

5. Was there a nexus between the changing role of African women in Benin Province and their under-development under post-WW I colonial policies in the oil palm industry? Before attempts are made to provide answers to the questions stated above, it is expedient to shed light on the concepts of development and growth as operationalized in this study. To this shall be turned the focus of the next section of this paper.

Conceptualizing growth and development

The conceptualization of growth and development has yielded itself to several acrimonious explanatory models. Some of these models have donned ideological garbs such as simply capitalist, communist or socialist. Another group of scholars view growth and development through a cultural or racial lens when it resorts to classifying them as Western, non-Western, Asian or African models. Yet, a third group conceives and portrays growth and development through the narrative models of gender differences, inequalities and exclusions.

While the classical school of thought is quick to draw a positive correlation between growth and development in any society or industrial sector which witnesses growth, the Marxist school is quick to counter that growth does not necessarily translate into development under the condition of unequal exchange such as characterized Metropolitan – Satellite relations. Instead, the latter argues that growth leads to the development of the Metropole and the underdevelopment of the Satellite (Rodney, 1972).).

Similarly, the Eurocentric cultural or racial school posits that growth necessarily brings about the modernization of an uncivilized race, where the donor culture is Western and the recipient culture is non-White. Therefore, the colonization of Africa has been rationalized as a ‘civilising’ mission in which the change agents were Europeans. The Eurocentric thesis, thus, is that the economic growth enforced under the post-World War I colonial economy led to the development of African societies, peoples and economies (Lugard, 1905).

The feminist school, on its part, has argued that African societies were generally patriarchal and that relations between men and women were necessarily oppressive and exploitative. They consequently bred inequality, exclusiveness and differential development in which the women were constantly on the receiving end of domination. This position has been countered with the argument that the relations between men and women were not necessarily oppressive, exploitative and exclusive but collaborative, fair and just (Ayokhai, 2015). This argument is sustained in this study.

In the midst of this divergence, one thing that is however common to all the perceptions and persuasions of growth and development is the ease with which theorists find a common ground when it comes to identifying the function which growth and development serves, or ought to serve, in society; that is the increment in the material conditions of persons and peoples across time and space.

Consequently, growth and development have been assumed to hold sway for the African women in the oil palm industry in Nigeria’s Benin Province under colonial rule by the classical theorists, while Marxists scholars have disputed the argument. The gender school aligns itself with the latter but conceives men as a class of oppressors who appropriated the surpluses created by women for their personal and group development. The theoretical underpinning of this study is that the historical reality of the practice of growth and development among women in the export oil palm industry in Benin Province provides ample evidence of a paradox. While it supports the thesis that growth in the oil palm industry did not bring about the development of the African women in Benin Province, it does not, however, agree that the exploitation and underdevelopment of the women were motivated and perpetuated by the network of social relations of production between men and women as argued by the feminist school of thought.

Rather, it perceives the exploitation and under-development of the women through the lens of the capitalist social relations of production that predominated under the colonial economy of the post-World War I era.

Benin province: An African territory in a British colony

For any meaningful exposition on the Benin area and its peopling, it appears expedient to begin with the city of Benin, capital of the Benin Kingdom, provincial headquarters of Benin Province, capital of the Mid-Western Region, Bendel State and presently, Edo State. This expedience arises from the nature and content of what has been passed on as the origins of the peoples and societies in the Benin area.

Two major assumptions by Ryder laid the foundations for some of the common assumptions often taken for granted on the origins of peoples and societies in the Benin area. Ryder had assumed that the origins of Benin kingdom were “lost in myth and antiquity, from which survives only a tradition of migration from the east that is common to many West African peoples (Ryder, 1897).” On the premise of the foregoing, he therefore made the second assumption on the origins of Benin Kingdom that:

To reconstruct its growth it is therefore necessary to work backwards from nearer and better known events which suggest that the process was not one of a number of groups coalescing, but the expansion of a city-state nucleus – something more akin to the emergence of states in classical Greece than in northern Europe (Ryder, 1897).

Most scholars of Benin history, including Bradbury (1957), Igbafe (1980), Okojie and Oseghale are in agreement with Ryder’s postulations since their accounts of the origins of the peoples and societies in the Benin area seem to coalesce around these assumptions and do not contradict them. Though, this position has been contested (Ayokhai, 2015), it is not within the scope of this study to elaborate on the argument. It, therefore, suffices for the purpose of this study to simply identify the various groups and societies that made up the territory of Benin Province.

Benin Province approximates the territories of peoples and societies which found themselves under the British colony of Nigeria. Benin Province dates back to1897 when it was subjugated by the British and existed up to 1960 when colonial rule was terminated in Nigeria. The heartlands of the Benin Kingdom occupied the south of Benin Province in what presently constitutes the southern senatorial district of Edo State, Nigeria. Though the exact extent of the territory of the Benin Empire is not known (Igbafe, 1980), the British colonial administration had created the Benin Division on the territorial unit over which the authority of the Oba was recognized after the restoration of 1914 and the Benin Province was extended over the assumed territory of the Benin Empire (Bradbury and Lloyd, 1957). The Benin Province was divided into namely; Benin Division, Esan Division, Asaba Division and Kukuruku (Afemai) Division.

The total area of Benin Division was about 4,000 square kilometres and the population, according to the earliest available census figure, Benin Division had a total population of about 292,000 in 1952 (Bradbury and Lloyd, 1957). Benin City, the seat of the Oba of Benin and headquarters of Benin Province, is called Edo by the inhabitants and ‘in certain contexts individuals from all parts of the kingdom will refer to themselves as Oviedo (child of Edo) or ovioba (Oba’s subject) (Bradbury and Lloyd, 1957). Their language is also known as Edo. Buttressing this fact, Ryder also notes that ‘The heartlands of the Benin Kingdom are inhabited by a people who call themselves, their capital city and their language Edo (Ryder, 1897).

Bordering the capital city of Benin Kingdom and later Benin Division to the north-east is the Esan people and their chiefdoms. During colonial rule they were reconstituted into Ishan Division of Benin Province. Presently they are found in the central senatorial district of Edo State less than one hundred kilometres north-east of Benin City, the present capital of Edo State. To the north-west and north-east, the Esan people are bordered by peoples and clans of Onwan, Akoko-Edo and Etsako respectively, while to the south and south-east are the Aniocha and Oshimili groups in present day Delta State. Immediately to the south-west, they are bordered by the Edo of Orhionmwon in the southern senatorial district of Edo State.

Further north of the Benin area are a handful of diverse groups. Unlike in the Benin and Ishan divisions where the people could conveniently be classified as Edo and Esan respectively, the northern area is a complex of several clan and village societies which were independent of one another up to the advent of colonial rule. It was impossible to describe them as a single cultural unit because no single culture had attained dominance over the others. They speak a handful of different dialects of the Edo language and the languages of the neighbouring Yoruba and Igbirra peoples, among others. They have also over time been subjected to cultural influences from their Igbo, Nupe, Igalla neighbours, in addition to influences from within the Benin (Edo) cultural area. For convenience, therefore, scholars have referred to them as simply the “northern peoples” of Benin Kingdom, Benin Province, Mid-Western Region (State), Bendel State, Edo State, depending on the historical context of the discourse. Culturally, they are roughly divided into three groups namely; Onwan people; Etsako people and Akoko-Edo people. This is seemingly along the lines of ethnic identity formations and hegemonies encouraged by the colonial project and subsequent state and local government creations in post-colonial Nigeria.

The peoples and societies were located in Kukuruku (later Afemai) Division of Benin Province. In the present political structure of Edo State, they occupy the northern senatorial district of the state. They are bordered to the south-east by the Esan people in the central senatorial district of Edo State and to the south-west by the Edo of Orhionmwon in the southern senatorial district of Edo State. To the north-west, they share boundaries with the Yoruba people of Ondo State, while to the north-east they are bounded by the Niger River and the Igalla people across it in Kogi State. Further to the north, they are bounded by the Ogori-Magongo and Igbirra peoples of Kogi State. From the foregoing, it is obvious that the Benin area, like most other parts of Nigeria, illustrates a case of peoples and societies at varying levels of social formation and a complex of cultures at varying degrees of evolution and diffusion. This is also manifest in the economic structure of the area up to the post-World War I epoch. Division of labour and economic specialization was along gender lines. Attention is turned to this aspect in the next section of this paper.

African women in the structure of production in the oil palm Industry

A prominent feature of the oil palm industry in Nigeria’s Benin Province is the structure of the division of labour and economic specialization along gender lines. This reality was succinctly captured in a memorandum to the Secretary, Southern Provinces, by the Acting Resident, Benin Province in 1924 when he stated that:

Among the natives of the province the men collect the palm fruit and bring it to their houses. In the Agbor District they sell the fruits to their women for 2d a bunch. The women then prepare the oil and kernels and market them and the proceeds are theirs. In the remainder of the province they do not buy the fruit but they return to their husbands the money they received for the oil retaining that received for the kernels.

In the cases that predominated in the province, it is noted that while the men were responsible for the harvesting of the oil palm fruit, it was the women who actually undertook the tasks of extracting oil and kernels from them, with men and boys providing additional support services at the de-pulping stage by either helping out with pounding or mashing. This practice is in tandem with Usoro’s observation in respect of Eastern Nigeria (Usoro, 1974). This situation substantiates the dynamism of the factor of the African women in the production system in the oil palm industry in Benin Province. Unlike in Eastern Nigeria, however, oil palm processing was not the preoccupation of men. It would not be out of place to note that there seems to be a correlation between the availability of alternative sources of export production in a given area and the degree of men’s involvement in oil palm processing, a traditional vocation of African women.

It is also noteworthy that it was the African women who actually undertook the trade in palm oil and kernels in Nigeria’s Benin Province. For instance, it was reported in the Annual Report of Benin Province for 1924 that:

Practically all the marketing is done by women who walk miles in order to attend the various market centres, such articles as palm oil and kernels only being snapped up by the native middlemen, generally a Hausa or Yoruba trader. The Binis take little pride in the markets and the Ibos are so saturated with fetish that their OMIS, or Queens of the Markets, are a menace instead of being a help to trade.

In the case of palm oil and kernels, it would appear that the women embarked on trade on behalf of their men, except in the Agbor Division where the men sold out the oil palm fruits to the women. There would appear also to have been a corresponding system of reward that supported this system of division of labour and ensured that the women were not subjected to undue exploitation by their men. For instance, while the women returned to their men the proceeds from the sale of palm oil, they retained for themselves the proceeds from the sale of kernels.

From what was earlier mentioned, it could be gleaned that the industry was not sufficiently stimulated by increased demand for oil palm products in the post-World War I era and the attendant colonial economic policies to cause a radical shift in the people’s perception of the industry as a subsidiary productive endeavour; hence it continued to remain largely in the hands of women just as it was in the preceding pre-colonial and pre-World War I eras. In the next section of this paper, attention is paid to the colonial policies in the oil palm industry and the changing role of African women in the post-World War I economy in Nigeria’s Benin Province.

Colonial policies in the oil palm industry and changing role of African women in post-World War I economy

With the amalgamation of the Colony of Southern Nigeria and the Protectorates of Northern Nigeria in 1914, Benin Province was incorporated into the Colony of Nigeria and came under the full application of British colonial exploitative economic policies. Women and the oil palm industry in Benin Province were brutally exploited in the ensuing growth and expansion that came to characterize the export trade between Britain and Nigeria in palm oil and palm kernel between 1900 and 1938. This section of the paper highlights the various colonial economic policies with a view to mapping out the trajectories of change in the role of women in the export oil palm industry in Nigeria’s Benin Province in the post-World War I era.

Before, we turn to the earlier mentioned efforts, it is imperative to state that the oil palm and its allied industries had provided vent for the innovative entrepreneurial abilities of African women in the Benin area of Nigeria prior to the colonial engagement with Britain in the post-World War I era (Ayokhai, 1965). The oil palm, thus, played a predominant role not only in the internal economy but also the social lives of the peoples and societies in the Benin area prior to the establishment of colonial rule and economy in Nigeria. For instance, it found utilitarian value in the food, nutrition, health, cosmetic, architectural, as well as marriage, birth, death and religious lives of the peoples and societies. This created a huge internal demand for products of the oil palm.

The African women in the societies in the Benin area rose up to the challenges of meeting most of the demand placed on the oil palm industry, including providing the science and technology base which sustained it (Ayokhai, 1965). Also, there is evidence that export trade in oil palm products was a part of the Trans-Atlantic trade that began in the fifteenth century. For instance, there are records of the procurement of palm oil by the Europeans that visited Benin Kingdom to trade in slaves (Ryder, 1969). The Oil Rivers Protectorate that later became the Niger Coast Protectorate, which Benin Province became a part of from 1897, was noted for its extensive trade in oil palm products with the Europeans during the era of ‘legitimate’ commerce. Therefore, it is out of tune with the existential trajectories of the historical realities of the oil palm industry in Nigeria’s Benin Province to reduce it to the narratives of a subsistence economy prior to colonial engagement with Britain. Rather, the industry had not only developed an internal market structure but also was evolving an international network of mercantile relations with Europe before the colonization and amalgamation of territories in the Nigeria area in 1914. What, therefore, took place in the industry between 1914 and 1938 was the expansion and growth of existing trading relations under unprecedented conditions of exploitation facilitated through the instrumentality of colonial economic policies and the exigencies of World War I.

For instance, at the inception of the colonial regime in the Nigeria area, the government’s position was that it was ‘the business of government not itself to engage in commercial enterprises of any kind, but to prepare and maintain the conditions – political, moral and material – upon which the success or failure of such enterprises in a very large measure depends (Clifford, 1920). This position was reinforced by Clifford in 1920 when he noted that:

…agricultural industries in tropical countries which are mainly, or exclusively in the hands of native peasantry (a) Have a firmer root than similar enterprises when owned and maintained by Europeans, because they are natural growths, not artificial creation, and are self-supporting, as regards labour, while European plantations can only be maintained by some system of organized immigration or by some form of compulsory labour; (b) Are incomparably the cheapest instrument for the production of agricultural produce on a large scale that have yet been devised; and (c) Are capable of a rapidity of expansion and a progressive increase of output that beggar every record of the past, for these reasons, I am very strongly opposed to any encouragement being given by the Administration for which I am responsible to projects that have for their object the creation of European owned and managed plantation to replace, or even to supplement, agricultural industries which are already in existence, or which are capable of being developed by the peasantry of Nigeria (Clifford, 1920).

The earlier mentioned statement is evident of the thrust of the post-World War I British colonial economic policy to keep the oil palm industry perpetually under the primitive/communal mode of production that prevailed during the pre-colonial economy. This was in tandem with the objective of colonial administration to minimize cost to it and increase revenue accruing to government. Efforts of the colonial administrations in the post-World War I oil palm industry in Nigeria were directed at expanding the production of export crops to increase government revenue. This was to be achieved by a combination of calculated policy measures which included the regeneration of oil palm groves, the encouragement of the establishment of small privately owned plantations, the introduction of improved seed varieties to peasant farmers and persuading them to adopt better cultivation practice. These measures were ensured the preservation of the communal mode of oil palm production. Usoro makes this point of the oil palm industry in Nigeria when he observes that the ‘...government’s basic policy was that there should be no major changes in the local system of palm products export production. Resource utilization and its organization in production should, as a result, continue under local systems adopted by farmers (Usoro, 1974).

Like in the rest of the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria, the method of production in the oil palm industry in Benin Province remained largely the same as in the pre-colonial era. For instance, oil palm continued to grow in the wild, while its exploitation was carried out by primitive means (Usoro, 1974). The extraction of palm oil still involved fermentation (boiling) of the oil palm fruit, de-pulping by pounding or mashing with the feet, and squeezing the de-pulped fibre by hand to obtain the oil. The palm nuts obtained in the process were dried in the sun, usually for about a month, and cracked with stone to obtain the palm kernel (Usoro, 1974). The process of extracting palm oil and kernels from the palm fruit had, therefore, not changed from what obtained in the preceding period. The drudgery of labour remained the same. To expand export outputs in the post-World War I era, British colonial economic policy, therefore, focused on the plunder of the wild oil palm fruits by ‘native’ male labour and the extraction of palm oil and palm kernels by the ‘native’ women in Benin Province.

Basically, oil palm production remained characterized by the natural groves. Colonial policy introduced the regeneration of groves and the cultivation of small privately owned plantations. The peasant farmers in Nigeria’s Benin Province found ridiculous the idea of regenerating the palm groves by means of removing naturally grown palms and replacing them with seedlings they had to procure from the nurseries of the colonial department of agriculture just because they presented a prospect of higher yield. There was also the question of ownership of the new palms since groves were communal assets. These reasons, therefore, sealed the fate of the policy on arrival (Ayokhai, 2015).

One of the early measures taken by the colonial government to improve the prospect of export production of oil palm products in Nigeria was to encourage individual farmers and groups to cultivate and own oil palm plots. In furtherance of this, the Agricultural Department initiated programmes for the development of improved seedlings for supply to farmers.One of the methods adopted by the Agricultural Department towards increasing the production of the oil palm was for Agricultural Officers to:

encourage a few of the more progressive farmers to adopt the new methods and to ensure by supervising each one of them individually that they should achieve a fairly high standard in the cultivation and maintenance of their plantations, which were to serve as example to others.

By the 1930s, efforts were intensified on small native-owned plantations, improving native extraction methods and providing palm seedlings. Despite growth in native-owned plantations, the total area cultivated was less than 10,551 acres in 1939. These were owned by some 5,602 individual peasant farmers. Most of these plantations were in the Benin and Owerri Provinces. Benin Province accounted for 61 per cent of the total acreage, while Owerri Province accounted for 17 per cent. Oil exports from these plantations amounted to about 2,907 tons in 1939, the equivalent of only 2.3 per cent of total exports (Lagos, 1940).

There is no doubt that this strategy worked fairly well since there is evidence to indicate ‘that in each of the Provinces... a number of such model plantations have been established and are being copied in increasing numbers.’The success of the model plantations and the satisfaction of the government with this initial innovation could be gleaned from the assertion of the Secretary, Southern Provinces that:

It is in fact out of the question for the officers of the Agricultural Department to attend to all the requests for instruction that are now being made and in His Honour’s opinion the time has come when the encouragement of oil palm planting and the instruction of prospective planters should become one of the first concerns of all Administrative Officers in the Southern Provinces.

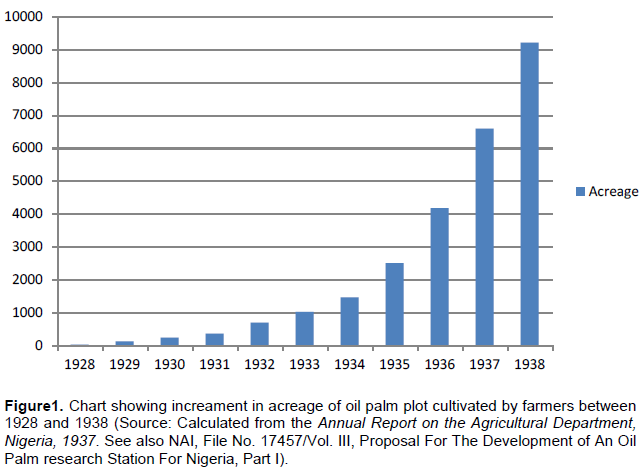

The outcome of this success is that the approximate annual acreage planted by farmers stood at twenty-one acres in 1928, one hundred and nineteen acres in 1929, two hundred and thirty-six acres in 1930 and three hundred and fifty-two acres in 1931. It rose to six hundred and ninety-one acres in 1932, one thousand and fourteen acres in 1933, one thousand, four hundred and fifty-seven acres in 1934 and two thousand, four hundred and ninety-eight acres in 1935. By 1936, 1937 and 1938, the acreage cultivated was four thousand, one hundred and seventy-two, six thousand, five hundred and eighty-eight, and nine thousand, two hundred and three respectively (Nigeria, 1937). Figure 1 shows the increase in the acreage of oil palm plots cultivated between 1928 and 1938.

From Figure 1, it can be observed that there was a significant increase in the acreage of oil palm plots cultivated in the Southern Provinces in the period between 1928 and 1938. If this is taken as representative of the post-World War I period (1914 to 1938), then we could as well suggest that the private ownership of the small oil palm plantation initiative was a success since it yielded the results desired by its initiators. This suggests that some farmers responded positively to the campaigns and propaganda carried out by the Extension Work Officers and the Administrative Officers across the oil palm belts. When the six thousand, five hundred and eighty-eight acres figure for 1938 is compared with the total of twenty-one acres cultivated in 1928, one cannot but conclude that the 1938 figure represents significant success in the attempt to stir local farmers in the direction of private cultivation of the oil palm. In fact, Benin Province accounted for 61 percent of the total cultivated acreage (Lagos 1940). The small privately owned plantations, though found acceptance among a few ‘progressive’ farmers only started in 1928 (Nigeria, 1937). Since the oil palm took about ten years from planting to harvest, this scheme could only have just started yielding result by the end of the pre-World War II period. However, in spite of the relative success of the policy, we cannot but reach the conclusion that when the ratio of those who responded positively is placed within the context of the population of farmers in Benin Province, the policy could not but be deemed to have failed since an overwhelming majority of native farmers did not respond positively to the initiative. The overall implication is that the alternative means conceived by colonial policy to increase production failed to achieve its objective and export production of palm products continued to be fully dependent on the resources of the wild palm and the drudgery of women labour up to 1938.