Review

ABSTRACT

This work is an attempt to highlight some landmarks in how the Zulu descendants engaged the issue of land with the settlers of any time in South Africa. The method of telling as it happened is a way to confront the history and try to find a natural way of rectifying land rights in settings where the customary land tenure system was overturned by the fortress based on the Western ways of land management. Dispossessed people’s land tenure situations are unique settings where even international actors have their ulterior motives and large interest and influence in the success of any restorative action or recovery. The study approach of telling it as it happened for the dispossessed, it represents real opportunity for practical and policy reform for the advocacy for restoration of customary land tenure system for everlasting peace. The trail of land handling from King Shaka, King Dingane, King Mpande, Cetshwayo and Dinuzulu is testimony of the trail of blood that went along the succession plan of Kingship which ceased to be hereditary from when King Shaka took over “ngeklwa”. The whites became aware of this and they got entangled in it for land. The South African Constitution Section 25 needs auctioning as it permeates expropriation without compensation for land reform.

Key words: Land expropriation, Zulu, without compensation, King Shaka.

INTRODUCTION

The issue of land in South Africa has transcended from pre-colonial, colonial, apartheid and post-apartheid scenarios. South Africa got democracy not by a barrel of a gun, but through negotiations as a result of multitudes of pressures directed to the Apartheid System. When democracy took over, new laws were given the opportunity to address land and property issues in the context of what is supposed to be more solidified and peaceful social and legal environment as an outcome. For purposes of this work, history is told as it happened without any underpinnings to commodification or allegiance to any affinity. The author tried to present history as a journey away from opaqueness about the truth. The article discusses the chronicle challenges regarding land as it got reduced from the hands of black people through the hands of the hegemonistic indigenous leadership which was under pressure of guises of assistance by white landless people gasping and punting for land at that time. The setting and tone of relating this history is not pinned to any practical and or policy options but narrates events as they happened. He threaded the events of land grabbing and how it was used as a collateral for military assistance by the Zulu Nation (dishing out within the Zulu Nation clan only from King Shaka to the just deceased (owakhothamayo King Zwelithini).

KING SHAKA

While the first white people to set their feet in South Africa were around the 1400’s, the arrival of white settlers started to be glaring in 1652 when Jan van Riebeeck came to build a refreshment settlement for the Dutch East India Company.

On his arrival he is praised by the Dutch Government or the colonial fraternity as a pioneering explorer and conservator of natural resources, while the other truth is that he was a recovering prisoner who was fresh from trial as an economic capturer of Batavia. Around 171 years later Farewell and Fynn arrived from Cape Town in 1823 as far as St. Lucia Bay and Delagoa Bay respectively. This was the concurrent time when King Shaka’s reign was at its infantry as he took over in about 1814 (Stuart, 1913:1). The Zulu resisted the thrust of whites, but encroachment on their territory was continuous, (Butler et al., 1978:9). Julian Cobbing was criticised as pushing a wrong path of histography for shifting the paradigm on Mfecane (Peires, 1993:295). The misappropriation of land and a resource in it dictated the shift from a domestic mode of production to a tributary mode. This happens during the King Shaka era and beyond. It motivated King Shaka to galvanise for sense of security as population explosion with competition to access to ecological resources was posing a threat to social security. The reintroduction of settlers caused the growth of the European colony on the Cape frontier and the Voortrekkers trekking inland later muscling up the Zulu Kingdom formation which King Shaka had started, expanded during King Dingane’s era (Wassermann, 2004:2; Globler, 2011). Drastic changes in the nature of external trade, particularly with the Portuguese on the east coast; (Kuper, 1993:470), all of these caused the Zulu kingship to galvanise for defence, for argument’s sake. The first white people to arrive in the Zulu kingdom were Fynn and Farewell who had a claim with King Shaka on land to settle in 1824, (Bramdeow, 1988:28). Maphalala reckons the whites met King Shaka when he was busy with the formation of the Zulu Nation and they were given Sibubulungu and the unoccupied surrounding area which was known as Port Natal by the whites, (Maphalala, 1979:4). Other historians allude that King Shaka recognized the Port Natal settlers as tributary chiefs in the same year, two years later King Shaka is supported by Port Natal traders with firearms to defeat the Ndwandwe people at the battle of the iziNdolowane Hills and before the Ndwandwe dust settles, in 1827 (Laband, 2009:xxiii). King Shaka’s relationship with King James is conceived when Francis Farewell went for a financial backing by Cape merchants for an exploratory voyage to Delagoa Bay and Natal, on ships the Julia and the brig, the Salisbury, which translated to a mature relationship, (Hamilton, 1991:6). The eventuality of the relationship decoded why an armed party from Port Natal under James King assisted King Shaka in subdjucating the Bheje people (Laband, 2009: xxiii). Amazingly, a year later in August, King Shaka, gets a warning from the whites not to expand his kingdom southwards. Now the people who has asked for land to settle while they find a way to repair their ship which had wrecked, are giving orders to King Shaka not to expand in his ancestral land, and on the 24th September he is assassinated, (Laband, 2009: 23; Maphalala, 1979:2). While as a contemporary writer there is a lot from Stuart that does not make sense, but this foregone allusion about King Shaka gets confirmed in his 1913 thesis which was funded by those who wanted to hear his “truth” the way it is told.

“Among these, practical services of various kinds were rendered by the pioneers from time to time, in a collective as well as individual capacity. For instance, they were occasionally called on to assist in military expeditions; when not so engaged, they established and developed a commerce in sundry commodities, notably blankets, cloth, bangles and beads of different colours and sizes, in exchange for ivory, cattle, goats, corn, maize, etc., which proved as beneficial to the aborigines as it was lucrative for the settlers (Stuart, 1913).

Most of the foothills of the eastern plateaux of the Zulu territory from King Shaka's day were invaded by Whites, (Butler et al., 1978:9), which gets confirmed by Shula when she alludes 2.6 million acres diminished and the Zulus were pushed back and only 3.8 million acres remained (Marks, 1970:127). From the mentioned voracious appetite of land the whites had, it is coincidental that King Shaka's death in 1828 took place just after the visitation he was paid by Farewell, Fynn and Isaacs at Kwa-Bulawayo, who on receipt of the news of King Shaka’s death, were more worried about permission he granted them to settle in Natal, and the latter their relationship between King Dingane and the traders at Port Natal was friendly, and the Qwabe tribe that killed lieutenant Farewell got punished severely (Maphalala 1979:3).While this line of argument does not dismiss the action by Prince Mhlangana, King Dingane and Princess Mkabayi being pivotal to the plan, the opportune time of the visitation by Farewell and Isaacs to King Shaka’s kraal becomes significant.

KING DINGANE

The Dutch people decided to trek away from the rule of Britain from the Cape to the interior in the 1830’s, (Knight, 2015:3). A party of Boers under Piet Retief arrived in Durban from the Cape Colony, through the coming of traders and missionaries, and their families, were considerably increased. The encounter of King Dingane with Retief was after the Great Trek took a turn in Tlokwe and veered down through the Drakensberg to Natal, (Globler, 2011:131). The first Black community thy found was the Khumalo ABeNtungwa who populated the entire area from Qgumaweni down to oThukela which is in Ntabamnyama. INkosi Nqina Khumalo pointed them to King Dingane in Mgungundlovu. On the 5th of November 1837, Retief visits King Dingane at his Royal Palace, (isigodlo), in uMgungundlovu isigodlo where they negotiated for land and King Dingane asked them to bring back his cattle which he said were stolen by Sigonyela (Laband 2009::24).. Literature coils they were to sign an agreement which Globler refers to as dubious as King Dingane was illiterate, so there was no way he could write an agreement and sign it, (Globler, 2011:130). King Dingane assumes a posture of great hostility against the whites hence his unwavering appetite to kill them any time without any proper scheme, (Kunene, 1979:299).

King Dingane was critical of endless fraternizing with Strangers as he harboured deep suspicions against them. He despised that they participated deeply to the affairs of the court. King Dingane detested this as a strategy to bring disaster to the whole nation as their love for land was like a disease. From page 4 to 5 Maphalala writes about King Dingane and his ordeal with the Voortrekkers led by Piet Retief and how they were clobbered to death with no witness to tell the story, until the Ncome Battle where King Dingane was defeated by the Boers. King Mpande joined the Voortrekkers in a joint attack on King Dingane. The Zulu army was defeated and chief induna Ndlela of the royal army returned to report his failure to King Dingane. He was violently berated by the king and accused of cowardice and negligence. King Dingane ordered his arrest and had him bound. Later, in full view of his fellow indunas, he was strangled with an ox-hide thong. Despite all his leadership hence King Dingane sustained him when he took over from King Shaka and made him his Commander in Chief (Laband, 2009:189,315). While there could be dual lenses through which Ndlela kaSompisi would be viewed, bearing in mind the approach of the Ncome Museum and the Blood River Museum. What is a main and sustained factor is that King Shaka appointed Ndlela and raised him to the highest echelons of his Militancy as he was the Chief Millitary Commander. This position cuts across Shaka and Dingane;s rule as he was not killed when Dingane took over, but he was Commander in the Voortrekker-Zulu War, the Ncome River Battle of 1838. Ndlela advised Dingane not to negotiate with the Voortrekkers instead should and execute Piet Retief (Laband, 2009:189). The defeat of Dingane by Mpande at the Civil War of Maqongqo Hills raised suspicion as Ndlela had his daughter married to Mpande and Dingane, like Shaka, had no son to be the next king. This is suggestive of the reason why Ndlela refused to support the killing of Mpande who had children.

KING MPANDE

While Napier reckoned the Voortrekker project was a disaster for the greater part of northern Natal, his interests were on preventing the Voortrekkers from offloading destabilised blacks who migrated away from Voortrekkers’ invasion to Mthamvuna and Mzimvubu, (Shamase, 1999:6). He ordered the soldiers to prevent the Volksraad from settling large numbers of Natal blacks in the area, (Rautenbach, 1989:22). These people of Dutch origin seek land and free African labour, (Porterfield, 1997:67). The alliance between King Mpande and the Voortrekkers was based on the Voortrekkers’ assistance to fight his brother King Dingane at the battle of Maqongqo which split the kingdom and land ceded to the Voortrekkers as a token of their assistance, (between 1839 and 1840 the Voortrekkers seized large parts of the Zulu kingdom, including the area between the Thukela River and the iMfolozi Emnyama (Bundy and Gordon, 2020:1). King Mpande promised to protect the Voortrekkers with his last men, and the promised got extended to 14 February 1840 where Pretorius issued a declaration whereby the territory from the sea next to the Black Mfolozi River, through the double mountains, close to the origin and then next to Hooge Randberg in a straight line to the Drakensberg, St. Lucia Bay inclusive was declared as border between KwaZulu and the Republic of Natalia, (Shamase, 1999:4). This relationship between the Voortrekkers and King Mpande saw him assisted at Maqongqo and installed as King of the Zulu subject by the Voortrekkers at Pietermaritzburg, (Porterfield, 1997:67) which unsettled the British as they went to threaten the Voortrekkers’ Sovereignty. Despite the fight which broke out on 23 May 1842, which presaged the first of several Anglo-Boer wars, some outdated history maintains the discovery of gold in 1884 caused the war, (van Heyningen, 2016). On the banks of the Klip River the Voortrekkers received about 36 000 head of cattle looted after the Maqongqo battle. In 1842 he gave land to the British through Napier using special agents and missionaries from sources of Mzinyathi to its confluence with uThukela, (Shamase, 1999:7). King Mpande also gave a lot of land to missionaries which their reason to present the Christian gospel to the Zulus is one of the guises Harriet warns about with the British settlers, (Colenso, 2010:29). On the line up for land were the American Board of Commissioners, English Wesleyan Methodist Society, Norwegian Mission, Berlin Mission, Hanoverian Mission, Church of England and Roman Catholic Mission, whereby King Mpande had hopes they will provide a buffer between his empire and the Colonial establishments in Natal (Shamase, 2015:2; Shamase, 1999:11; Muntu, 2006:1).

KING CETSHWAYO

KING DINUZULU

Dinuzulu formed an alliance with the Boers from the Transvaal who had for decades invaded western Zululand for grazing to aid him fight Zibhebhu, (Wassermann, 2011:26). Dinuzulu’s act of forming a combined force with people who had always showed an overwhelming appetite for land was an irresponsible act to his followers as the land they had been given to them by Mvelinqgangi. The price of 2 700 000 acres of land populated by his loyal followers had to be ceded and from that day Zululand was engaged by the English and the Dutch, some of it even today. On this land, the Boers formed the New Republic with Vryheid as its capital and Lucas Meyer as the President. Beyond the 2 700 000 acres they took from Dinuzulu, they thieved more than discussed and the right to a protectorate over Dinizulu, the British intervened by recognising, in October 1886, the New Republic. The Boers dropped the thieved land on condition that those who had settled in that area retain their farms. Protests by Dinizulu and his followers fell on deaf ears and Britain on the 15th July, 1885, through the Natal legislative council executive responded by annexing Zululand, including Proviso B, and turning it into the British Colony of Zululand, (Maphalala, 1979:11).

HENRY FRANCIS FYNN

With King Shaka’s permission, Henry Francis Fynn settled on the banks of the Umzimkulu River, south of Natal, where he got married and became a chief and had his Nsimbini tribe (Bramdeow, 1988:6). King Shaka's death in 1828 took place shortly after the return of Farewell, Fynn and Isaacs from their successful visit to his royal kraal at Kwa-Bulawayo.

When news of his death reached the whites, they were very upset because King Shaka had granted them permission to settle in Natal, (Maphalala, 1979:3), and they got worried if King Dingane will ever entertain that. The historical confusion happens when Mkhulu Mavundla in Mbele and Houston thesis concurs King Shaka did not just give Fynn the permission to trade in Durban but this got extended to land around the Port Shepstone area. This extension is questionable as King Shaka got murdered shortly after the Henry Francis Fynn and John Dunn visited KwaBulawayo isiGodlo. Mbopha who was ostracised by his own people, the Bafokeng, which he was a rightful heir, migrated to kwaZulu and joined King Shaka as his right-hand man (insila). He is used in killing King Shaka, hence his last words, “Nawe Mbopha kaSithayi”. Mhlangana got killed by King Dingane while Mbopha fled and settled round where Gamalakhe in Sayidi (Buthelezi 1983), (Port Shepstone), is today and changed his name to Mvundla, hence the AmaVundla., (Mbele and Houston, 2011:144). The coincidence of Fynn characterised as a freebooter, and their visit to King Shaka’s kwaBulawayo sigodlo and King Shaka’s sudden death, and the fact that he killed a Zulu chief named Lukilimba and his deteriorating relationship with the Zulus, (Bramdeow, 1988:2) his unyielding appetite for land. Marjory Davies has a decidedly European bias. Although Davies, the great grand-daughter of William Mc Dowe ll Fynn, brother of Henry Francis Fynn also known as Mbuyazi, concentrates on her lineage she focuses only on Henry Francis Fynn and his white descendants and neglects Henry Francis' more numerous descendants of mixed ethnic origin, which bothers into a racial burden where some people are captured in the notion that racial mixture is something derogatory (Adhikari, 2013:8).

JOHN DUNN

Following his parents ?deaths, a teenaged Dunn left the nascent colony for Natal”s borderlands, eventually moving to Zululand in the 1850s. His movement to Natal in 1851 was to obtain land which caused bad blood between him and the white government, (Bramdeow, 1988:3). Dunn later served as a sub-chief under the Zulu monarch Cetshwayo (1873-1879) before changing allegiances during the Anglo-Zulu War; he was subsequently appointed chief over a Zulu district by the British government following Cetshwayo’s defeat” in 1879. This is a lesson as it is known in history of the Nguni people that ”Umlungisi uzithela isisila”. The interpreters very likely had their own particular interest in communicating a version of history palatable to their masters.

LAND IN THE HANDS OF INGONYAMA YAMAZULU

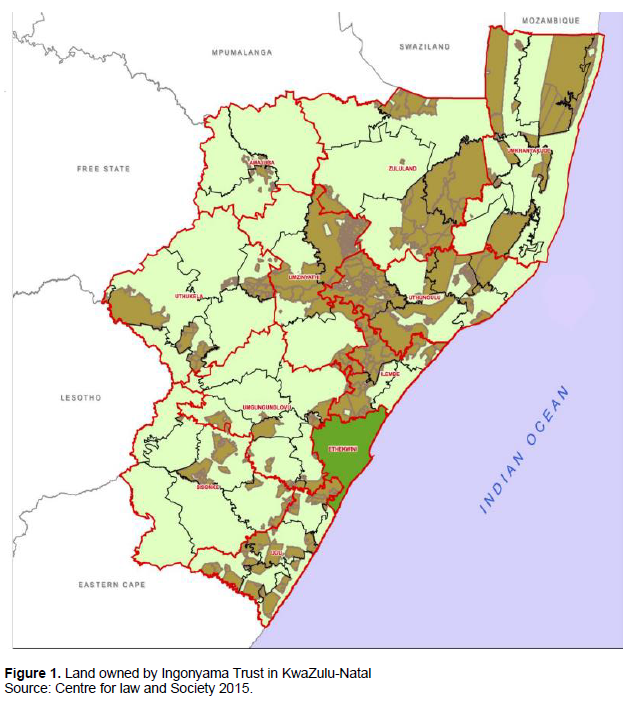

The Royal Zulu Kingship itself never had any political boundaries in as much as the whole of Africa as a continent (Amadife and Warhola, 1993:553), until the scramble for the Southern part of Africa by colonial invasion. Ingonyama Trust Board is a Schedule 3A Public Entity in terms of the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA). It is responsible for the administration of the affairs of the Ingonyama Trust. The Ingonyama trust was established in 1994 by the erstwhile KwaZulu Government in terms of the KwaZulu Ingonyama Trust Act, (Act No 3KZ of 1994) to hold all the land that was owned or belonged to the KwaZulu Government. The mandate of the Trust is to hold all this land for the “benefit, material welfare and social well-being of the members of the tribes and communities” living on the land. The sole trustee to land is under Ingonyama Trust His Majesty the King of the Zulus, as the holding is in trust for the Zulu Nation (Ngwenya, 2020:5). This was also one of those last minute hems which nearly reduced the country to wasteland like the Anglo-Dutch War, (van Heyningen, 2016:999). The map on Figure 1 displays land that is accessible to the Zulu Monarchy under Ingonyama Trust. This ownership transcends into all tribes in South Africa, like the Bafokeng in North West where the ownership of land is on behalf of the people. The influence of the white to impoverish black people has never been confined in KwaZulu, but the footprint of the colonial governing authorities got extended everywhere in South Africa. This had social and economic consequences of the wars of dispossession; the interference of the colonial government and the missionaries in the relations even between amaGcaleka and amaMfengu (Mvenene, 2014:38).

These interconnections among collective identity struggles, land struggles and state policies and practices in post-apartheid South Africa, are confused by the government's contradictory policies and ambivalent practices (Turner, 2013:507).

INGOYAMA TRUST ACT CONTENTS

Key provisions of the act

Section 2(2) – provides that the Trust shall, in a manner not inconsistent with the provisions of this Act, be administered for the benefit, material welfare and social well-being of the members of the tribes and communities as contemplated in the KwaZulu Amakhosi and Iziphakanyiswa Act.” Section 2(3)- “The Ingonyama shall be the trustee of the Trust which shall be administered subject.

The Act that gave birth to the above setting in Figure 1 as established on the 24th April 2004 resulted in a new landscape whereby:

a. Land owned by the iNgonyama Trust at 2 700 000 ha.

b. The population within iNgonyama Trust Land at 4558 698.

c. Traditional Authorities at 241.

d. Section 2(4) - bides the Ingonyama to deal with land with reference to section 3(1) in accordance with Zulu indigenous law or any other applicable law.

e. Section 2(5) - which accentuates the powers of the traditional authority, who in turn obtains a written concern from community members which then gives power to the Ingonyama to encumber, pledge, lease, alienate or otherwise dispose of any of the said land or any interest or real right in the land

f. 2(7) –promoting any national land reform programme established and implemented in terms of any law shall apply to the land referred to in section 3(1): with consultation with Ingonyama.

g. Section 2(8) – which upholds existing rights and interests and protects them against any infringement by Ingonyama?

THE SOUTH AFRICAN DEMOCRATIC ENGAGEMENT OF LAND ISSUE: LEGAL FRAMEWORK ON LAND

Besides the land which has to do with the Zulu Monarchy, there is land which is outside the confines of the Ingonyama Trust. Some of that land was once privately owned by people who bought land when Reverend Colenso advised so The South African Constitution provides for the land restitution programme in section 25(7) and section 25(5); Section 25(7) which situates that an individual or community dispossessed of property after 19 June 1913 as a consequence of past racially discriminatory laws or practices is eligible to restitution of that property or to equitable redress through restitution, land redistribution and tenure security. This law becomes a problem as it looks at dispossessions as some event that just happened in 1913 and forcible removals are not spelt out clearly. If a person was forcibly removed, there should be no negotiation on redressing that situation. People lost land from the day white people came to South Africa. Land was what they wanted. The following is part of our Section 25 of the Constitution through programmes of restitution, which aimed to return land to Africans who had once had title and lost their property during the apartheid era (p.32). That was going to be done through redistribution, restitution and tenure as spelt out in the subsequent paragraphs a) Redistribution, using government subsidies to buy farms and tenure reform (Provision of Land and Assistance Act, 126 of 1993, as amended by Act 58 of 2008 (Section 10); b) Tenure reform which aimed to safeguard the rights of residents of white farms and state land in the former homelands and thus protect poor people from summary eviction by securing their existing rights or by buying alternative land on which they could live” (Moore, 2011: 33). c) The last bout on land has been the land expropriation without compensation, which is highly contestable. This is extended by arguments which Kloppers and Pienaar wrote about from page 677 to page 678 (Kloppers and Pienaar, 2014:677-678), which reminds one that indeed the Holocaust was a racial crime perpetrated against racialized whites in Europe, (Ce´saire in Mignolo, 2007:155). All what these authors worry about, is none of the dispossessed people’s problems as land grabs were introduced by the white colonialists with their expansionist project, voyages of discovery and explorer conservationists with the eventuality of from Cape to Cairo projects. The land they possess is entangled with a long umbilical cord of racialized dispossessions (Moyo, 2015:108). With the act of their Parliament, they promulgated all notorious acts to disposes Black people of their land without compensation. The pharmaceutical industry intends using same apparatus and laboratories.

Squatters Act (No: 11) of 1887

This is one of the acts of parliament which disenfranchised thousands of indigenous communities who found themselves being called squatters in the ancestral land. The South African Republic (ZAR) government promulgated the Squatters Act to regulate 'squatting' on White owned farms. In terms of the Act, not more than five families of Blacks were permitted to live on farms. This caused a lot of forced removals as when blacks have exceeded five families, they would be removed. The blacks would provide cheap labour to white farm owners.

NOTORIOUS ACTS

Natives Land Act (No: 27)1913

This act prohibited the indigenous people from buying or hiring land in 93% of South Africa as its section 1, sub section ‘a’ says, “a native shall not enter into any agreement or transaction for the purchase, hire, or other acquisition from a person other than a native, of any such land or of any right thereto, interest therein, or servitude there over.” The 1913 Natives Land Act and the so called Mfecane were seen as accomplishing the thieving process of black man’s land by foreigners, as both are referred to as close companions, (Cobbing, 1984:16).

The native administration bill 1917

This was a Bill that made recommendations for acquiring more land from Black people on a scale that was even broader than the Natives Land Act of 1913.

Prevention of illegal squatting Act (No: 52) 1951

This anti-squatting act forced private landowners and local government authorities to demolish and remove all structures or buildings that were built without permission of the land owner.

Bantu laws amendment act (No: 42) 1964

This law gave the government the power “to expel any African from any of the towns or the white farming areas at any time" (Thompson, 1990:199).

The group areas act of 1950

The Population Registration Act No 30 of 1950 is one of the pillars of Apartheid and had to be promulgated to lay a foundation for the Group Areas act of 1950. The Population Registration Act required people to be identified and registered from birth as one of four distinct racial groups: White, Coloured, Bantu (Black African), and other. Apartheid model of the city was a commercial city centre, transitional mixed-use area, white residential, coloured residential, black residential on outskirts.

The native land act of 1913

Theophilus Shepstone, in 1846 drove the Native Policy of the British Natal, in 1847 managed the Locations System which is the reason why the years between 1843 to 1855 are registered as “Shepston’s System”, as this system caused Africans to be relegated to reserves and rocky lands which continues to haunt the post-Apartheid generation (McClendon, 2002:531). The ANC-led Government has caused a lot of pain to the remaining Elderly of the dispossessed indigenous South Africans by fixing dispossession in 1913 as if one was dispossessed on the 31st December 1912 that makes a huge difference from the person dispossessed the following day in 1913. The day the land-grabbers promulgated the 1913 Land Act continues to haunt Black people as the Whites who grabbed the land in 1912 are secured with stolen continuing the legacy of a generational wealth for their generations when its actual owners continue to suffer landlessness. Dispossessions were in gradations and people were moving away from visible places to deep areas in mountains and forests so they did not even know when they felt actual dispossession as this was a political issue where people would negotiate their existence. This becomes a legacy of neoliberalism that benefits the white elite and global capital system, (Mudau, 2021:1).

Despite all the policies which were instituted during the period from 1991 to 1997, which were aimed at abolishing racially-based laws and practices related to land, 70% of land is still in the hands of white people in South Africa. Section 25(3) of the South African Constitution spells the calculation of just and equitable compensation of land is governed by s 25(3), which reads:

“The amount of the compensation and the time and manner of payment must be just and equitable, reflecting an equitable balance between the public interest and the interests of those affected, having regard to all relevant circumstances, including:

(a) The current use of the property;

(b) The history of the acquisition and use of the property;

(c) The market value of the property;

(d) The extent of direct state investment and subsidy in the acquisition and beneficial capital improvement of the property; and

(e) The purpose of the expropriation.”

Furthermore, the same section 25 allows for the expropriation without compensation, which has been highlighted as some event that once happened in the history of the country as far back as 1915, where the Appellate Division recognised that Parliament had a right to expropriate without compensation (Ngcukaitobi and Bishop, 2018:1). What remains a mystery is how people who expropriated the land without compensating the black people (Atuahene, 2011: 121) expect to be compensated. Moreover, lawyers maintain that there is no need to amend the Constitution as it permeates expropriation without compensation if that is to advance land reform, (Ngcukaitobi and Bishop, 2018:2). The application of the 1913 Land Act as a significant landmark of dispossession of land which was inflicted by Whites in South Africa is contentious rhetoric application of a polemic discourse aimed at supporting a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. While authorship applaud the post 1994 era which saw women winning cases of land claims (Sihlali 2018). The illiterate dispossessed ageing frail members of the indigenous societies are locked outside their ancestral lands by Whites whose ancestors stole the land and the state thinks that is so constitutional. The gap on legalistic and litigious culture is so wide as from day one the whites grabbed the first piece of land in Zululand, whetted their appetite for stealing more land, and they closed doors of social institutions they found here which would have evolved technically, technologically and otherwise. The ANC-led government positions the White Farmers to have available to them a repertoire of moves denied to their Black counterparts (White, 1992:54).

LAND AND POWER

In Quijano’s seminal article the colonial matrix of power has been described in four interrelated domains: control of economy (land appropriation, exploitation of labour, control of natural resources); control of authority (institution, army); control of gender and sexuality (family, education) and control of subjectivity and knowledge (epistemology, education and formation of subjectivity). With what Quijano puts forth, the author conceptualised that the land that has been syphoned from black ownership to foreigners has never been bought but blacks were forcibly removed and given dry and mountainous areas. The economy was developed from the centre and black people were at the periphery. They would move from the periphery to the centre to provide labour, sometimes without pay. Squatters would pay for their squatting with labour. Paying for a stay in your ancestral land, which leaves much to be desired if the present government believes the paradigm has shifted as people are still dispossessed.

CONCLUSION

Indigenous communities have a special affinity with land. The sense of ownership as a property in their land is about asserting a permanent physical kinship and an in-depth spiritual relationship with their land. This claim is about the legitimacy of one's personal space in a specific land as they assert that the land is 'proper' to them and they have, as an electorate, a significant self-constituting identity with the land. This spiritual connection with the land acts as a measure that venerates their origin to the soil, as they daily traverse in it, consume its waters and gaze through its firmament and their destined internment. The land confirms an embodiment of one's personality and autonomy. To indigenous communities in South Africa, the property in the soil means the appropriation of a limited form of sovereignty over the land and not a generic of it. This means selling of land or exchanging it for another land was never an option as they say the soil is where one originates, (uhlanga lomhlabathi), where one’s body waste is deposited(ukusala kwensila) and where their navel gets deposited, (inkaba yakho isala khona) as a reminder of place of origin. It is to allege the emotion and an invested compounded relationship with the ancestors as the land presages an ultimate, a deeply instinctive self-affirming sense of belonging and control. Being buried in their soil is a negotiation for a permanent spiritual rest and to attain that one would have had an organically sanitized relationship with the people of that land, which is a reason why when a visitor was sick to die, that visitor would yearn to die in their proper domicile.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adhikari M (2013). Burdened by race: Coloured identities in Southern Africa Edited by Mohamed Adhikari Burdened by race: Coloured identities in southern Africa. Cape Town: 2009 © University of Cape Town. |

|

|

Amadife E, Warhola J (1993). Africa's Political Boundaries: Colonial Cartography, the OAU, and the Advisability of Ethno-National Adjustment. International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 6(4):533-554. |

|

|

Atuahene B (2011). South Africa's Land Reform Crisis: Eliminating the Legacy of Apartheid. Foreign Affairs 90(4):121-129. |

|

|

Bramdeow S (1988). Henry Francis Fynn and the Fynn Community in Natal 1824-1988. |

|

|

Britannica T Editors of Encyclopaedia (2019). Anglo-Zulu War. Encyclopedia Britannica. |

|

|

Bundy C J, Gordon DF (2020). South Africa.Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, incorporated. |

|

|

Buthelezi MG (1983). At Imbali, Pietermaritzburg, on the occasion of 'King DinganeKing Dingane's Day. |

|

|

Butler J, Robert I, Rotberg RI, Adams J (1978). The Black Homelands of South Africa: The Political and Economic Development of Bophuthatswana and Kwa-Zulu. Berkeley: University of California Press. |

|

|

Canwell D (2004). Zulu Kings and their Armies. Pen and Sword, 30 Sep 2004, History. |

|

|

Colenso H (2010). The Historical Image of King Cetshwayo of Zululand: A Centennial Comment. Natalia, Natal Society Foundation. |

|

|

Cope RL (1995). The Origins of the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. |

|

|

Globler J (2011). The Retief Massacre of 6 February 1838 revisited. Historia 56(2):113-132. |

|

|

Hamilton C (1991). The character and objects of Chaka: A re-consideration of the making of Shaka as Mfecane "Motor".University of Witswatersrand African studies institute. |

|

|

Kloppers H, Pienaar G (2014). The historical context of land reform in South Africa and early policies. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal/Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad 17(2):676-706. |

|

|

Knight I (2015). The Anatomy of the Zulu army: From Shaka to Cetshwayo, 1818-1879. Greenhill Books Frontline Books. |

|

|

Kunene M (1979). Emperor Shaka the great: A Zulu epic. Heinemann, London. |

|

|

Kuper A (1993). The 'House' and Zulu Political Structure in the Nineteenth Century. The Journal of African History 34(3):469-487. |

|

|

Laband J (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Zulu Wars. Historical Dictionaries of War, Revolution, and Civil Unrest, No. 37, The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Oxford. |

|

|

Maphalala SJ (1979). The participation of the Zulus in the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902.University of Zululand, KwaDangezwa. |

|

|

Marks S (1970). Reluctant Rebellion. Oxford, 127. |

|

|

Mbele T, Houston GFP (2011). KwaZulu-Natal History of Traditional Leadership .Leadership. Human Sciences Research Council Democracy and Governance, Cato Manor. |

|

|

McClendon T (2002). "The Man Who Would Be Inkosi: Civilizing Missions in Shepstone's Early Career." Journal of Southern African Studies 30(2):339-358. |

|

|

Mignolo WD (2007). Introduction, cultural studies. Routledge Taylor & Francis 1:21:155-167. |

|

|

Mudau J (2021). Land Expropriation without Compensation in a Former Settler Colony: A Polemic Discourse. African Renaissance 18:3. |

|

|

Mvenene J (2014). A social and economic history of the African people of Gcalekaland, 1830-1913. Historia 59(1):59-71. |

|

|

Muntu ME (2006). Zulu perceptions and reactions to the British occupation of land in Natal Colony and Zululand, 1850-1887: a recapitulation based on surviving oral and written sources. |

|

|

Ngcukaitobi T, Bishop M (2018). "The constitutionality of expropriation without compensation", paper present at the Constitutional Court Review IX Conference, held at the Old Fort, Constitutional Hill, 2-3 August 2018. |

|

|

Ngwenya SJ (2020). Suplementary submission by the Ingonyama Trust Board (ITB), on the ground of Land Tenure Rights Amendment Bill. |

|

|

Peires J (1993). Paradigm Deleted: The Materialist Interpretation of the Mfecane. Journal of Southern African Studies 19(2):295-313. |

|

|

Porterfield A (1997). The Impact of Early New England Missionaries on Women's Roles in Zulu Culture. Church History 66(1):67-80. Rautenbach TC (1989). Sir George Napier en die Natal se Voortrekkers, 1838-1844. Historia 34(2):22-31. |

|

|

Shamase MZ (1999). The Reign of King Mpande and his Relations with the Republic of Natalia and its Successor, the British Colony of Natal. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History, University of Zululand. |

|

|

Shamase MZ (2015). Relations between the Zulu people of Emperor Mpande and the Christian missionaries, c.1845-c.1871.Department of History, University of Zululand. |

|

|

Sihlali N (2018). A reflection on the lived experiences of woman in rural Kwazulu-Natal living under Ingonyama Trust. Agenda 32(4):85-89. |

|

|

Stuart J (1913). The Zulu Rebellion 1906 and of Dinuzulu's Arrest, Trial and Expatriation. Macmillan and Co., Limited St. Martin's Street, London. |

|

|

Sutherland J, Canwell D (2004). Zulu Kings and their Armies. Pen and Sword. |

|

|

Thompson L (1990). A History of South Africa (1990-09-10). The Yale University Press 1:1615. |

|

|

Turner R (2013). Land restitution, traditional leadership and belonging: Defining Barokologadi identity. The Journal of Modern African Studies 51(3):507-531. |

|

|

van Heyningen E (2016). The South African War as humanitarian crisis. The evolution of warfare. International Review of the Red Cross 97:900. |

|

|

Wassermann MJ (2011). The Anglo-Boer War in the Borderlands of the Transvaal and Zululand, 1899-1902. Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies 39((2):25-51. |

|

|

Wassermann MJ (2004). The Natal Afrikaner and the Anglo-Boer War. Doctor Philosophiae in the Faculty of Humanities (Department of History and Cultural History) at the University of Pretoria. |

|

|

White JB (1992). The Invisible Discourse of the Law: Reflections on Legal Literacy and General Education. Mountain View, California: Mayfield Publishing Company. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0