Rorya is one of new districts in Tanzania established in 2007. The district is a reflection of typical rural life in Africa South of Sahara where rural communities inhabiting dry woodlands and dependent on natural resources for their sustenance do not consider indigenous tree species as valuable resources of income. The study was conducted in the low lands of Rorya district-Tanzania to assess contribution of wild Acacia species for sustenance among rural communities. Ethnobtanical survey and standard sapling procedures were used for data collection and description of Acacia distribution patterns. Distribution and diversity of Acacia species is affected by multiple factors some of which could not be addressed by the arithmetic models employed in this study. Of all the sampled Acacia species, A. seyal ranked topmost as potential tree resource for a wider local and cross border market. Unlike other sampled Acacias, A. seyal has comparatively rapid biomass turnover within a short period. Density of A. seyal is much higher in swampy black cotton soils. Despite the economic potential of the species, significant proportion of Acacia woodlands is cleared annually for charcoal. Though Acacia seyal stumps coppices readily, combination of clearing and over grazing can convert the Acacia woodland to typical grasslands within a shorter duration of 20 years. At the same time, there is neither a conservation guideline nor land tenure arrangement in place for sustainable conservation. The study is recommending urgent legislative and land tenure reforms to control the current free access and encroachment that has nastily denuded the wood lands. Acacia being good source of pollen, commercial placement of bee hives is advocated as a supplementary economic activity in parallel with selling of wood fuel.

Life on the earth is totally dependent on the natural resources which are the resultant of structure and functioning of the ecosystems. The ecosystem provides services which regulate the cycling of material and nutrient and flow of energy among organisms (Bargali et al., 1992a, b; Parihaar et al., 2014; Bargali, 2018). Anthropogenic pressures lead to land degradation and reduced the natural resources at an alarming rate during the recent past (Padalia et al., 2017; Bargali et al., 2018; Bargali et al., 2019). Due to this the pressure on easily available and more productive resources increased continuously and have been pushed towards the threat which needs the sustainable management and utilization. Rorya district in Tanzania is a mirror image of other areas in the world and in African region with similar ecological degradation and social economic challenges. The district is characterized by regular hunger, poverty, draught and over dependence on natural resources for survival (Mugini, 2012). Up to 1980s the study area was fairly covered with intact vegetation with Acacia seyal and A. sobusta being dominant species especially in Mori and Nyaburongo valleys. These two valleys have approximate dimensional stretches of 20x40 km and 25x10 km for Mori and Nyaburongo valleys respectively thus accounts to about 10% of the forest cover in the district. According to 2012 national census (Wikipedia, 2020), Nyaburongo and Mori Valleys served approximate population of 83,767 in 6 wards including Nyathorogo - 14,809 people, Rabour - 11,259, Kisumwa - 12,447, Komuge - 13,651, Nyamunga - 13,161 and Kyang'ombe - 18,438.

Communities around the said woodland have been dependent on these natural resources for firewood, poles, timber, bricks burning, farm hedge, logs, thatching grass and grazing. The valleys have been water catchment for rivers Mori, and Nyaburongo for supported fishing of Mud and Lung fish. Nevertheless, the fish particularly lung fish have disappeared from the rivers following the current biodiversity loss and tremendous decline in water catchment capacity. Besides, the biodiversity loss in the past three decades was exacerbated by the emergence of commercial charcoal making and supply of logs for Co-Bricks factory specialized in burnt earth bricks. Consequently, the woodland was quickly converted to grassland by roughly one-third within a span of 30 years from late 1970s to 2000. Charcoal business is regarded as source of quick money among the youth compared to traditional livestock keeping and peasantry. Majority of active age group embrace charcoal burning with a consequence to Acacia woodland fast shrink. Moreover, fast annual population growth rate at 2.8% hiked demand for farming land and consequently encroachment into the Acacia woodland for settlement and new farms. Preference for charcoal by rural communities is gradually surpassing use of firewood and is perceived as a civilization. Disappointingly there has never been a tree planting culture or a habit for conserving natural forests in the area. Destruction of Acacia woodland in Rorya district is aggravated by lack of legislations against free access and chopping down of natural vegetation. Consequently, the woodlands have been a typical common property as they do not fall within the customary jurisdictions that are labeled with cultural restrictions. Quality of the Acacia woodland plunged further with the increased herds of cattle. The objective of this study was to advocate establishment of local legislations and land tenure reforms for restored productivity of the Acacia woodlands in the Mori and Nyaburongo valleys for improved livelihoods and ecological resilience.

Study area

The study was carried out between October 2002 and November 2018 in the catchment areas of rivers Nyaburongo and Mori in Rorya District located at Latitude 1°02' - 1°32'S and Longitude 33°45' - 34°35'E (Figure 1). The land in the study area consist of gneiss, quartz and schistose rocks, covered in the elevated parts with marl and red clay, and in the valley with a rich black loam (Lyaruu and Eliapenda, 2001).

Ethnobotanical survey

Ethnobotanical survey on Acacia Mill. (also applies to genera Senegalia Raf., Vachellia Wight and Arn and Faidherbia A.Chev.) was conducted to optimize their sustainable uses for environmental and socio-economic development. Semi-structured interviews from 94 correspondents, standard field inventory and participant observation techniques were used to collect information. Main ethnobotanical uses were fuel wood (charcoal and fire wood), agriculture, grazing, extraction of construction poles, other wood based uses and herbal medicines. In order to assess the consumption of charcoal, estimates were done at two permanent stations. Recording was done from August 16 to September 14, 2014 when extraction for charcoal is at the peak. The recording could not capture information on charcoal consumed locally in villages. One bag of charcoal = 28.4 kg of round wood (Ishengoma, 1982).

Sampling for quantitative estimates

Four transect lines were established, one line along either sides of each of rivers Mori and Nyaburongo at an interval of 200 m away from the real course of the river. This was done to avoid likely bias by high stocking along the river banks. Sampling plots were placed systematically along the transects at 1 km intervals.

Nested quadrat sampling method according to Stohlgren et al. (1995) was used to sample plants within the sample plots. Each sampling plot was partitioned into three levels of sampling; trees were enumerated in big quadrats measuring 50 x 20 m, shrubs in 5 x 2 m quadrats, herbs were sampled in smaller quadrats of 2 x 0.5 m. For the case of Acacias, there were no herbs so the inner quadrat was skipped.

Data analysis

Various models were used to analyze the effect of plant use by local communities to the diversity and distribution of plants in-situ. Some equations indicate quantitative preference to a particular plant by local communities presented as follow.

Use value (UVs)

This is the arithmetic model used to determine plant species commonly used by many informants for a particular ethnobotanical use category. The higher values of UVs for a particular plant are an indication of more preference or higher use frequency and vice versa.

Ethnobotanical uses

Eleven species of the previous broad genus Acacia Mill. were recorded namely Acacia seyal (Delile) P. Hurter. (Vachellia seyal), Acacia polyacantha (Willd) Seigler & Ebinger. (Senegalia polyacantha), Acacia robusta (Burch.) Kyal. & Boatwr. (Vachellia robusta), Acacia hockii (De Wild.) Seigler & Ebinger. (Vachellia hockii), Acacia drepanolobium (Harms ex Y.Sjöstedt) P.J.H.Hurter. (Vachellia drepanolobium), Acacia senegal (Linn.) Willd. Acacia lahai Steud. & Hochst. ex Benth. (Senegalia lahai), Acacia nilotica (L.) P.Hurter & Mabb. (Vachellia nilotica), Acacia xanthophloea (Benth.) Banfi & Galasso. (Vachellia xanthophloea), Acacia tortilis (Forssk.) Gallaso & Banfi. (Vachellia tortilis), Acacia brevispica Harms (Senegalia previspica) and Acacia albida (Delile) A. Chev. (re-clasified as Faidherbia albida).

Several ethnobotanical use categories were mentioned by respondents on the use of species, however for the sake of clarity, only major local uses were recorded including agro-forestry, bricks burning, charcoal, cow pen, firewood, fodder, farm hedges, logs, medicine, poles, food, posts rafters, resins, shade, sledge, timber and tool handles. Bee keeping was mentioned as one of the potential economic activity that can be pursued in the woodland, however because the area is a public land with free access. The investment is not feasible with the current economic trends unless some adjustments in land use are introduced to support the initiative.

Fuel wood

All residents of rural Rorya District use firewood as a source of fuel. The most preferred species for firewood are hard, low burning, non-succulent, less smoky wood in an order from Teclea nobilis, Rhus spp and Acacia spp. Traditionally, firewood for domestic use involve collection of naturally dry twigs, except for mass collection during ceremonies. This household consumption of firewood has negligible effect to the plant diversity. Consumption of firewood per household in Rorya District was estimated at 2±1 headloads per week. Similarly, Kajembe et al. (2004) reports consumption of firewood per household in Mawiwa-kisara catchments Forest in Kilosa District, Tanzania as 1 to 7 headloads per week with an average of 3 headloads per household per week. High demand of firewood hoists by increasing demands both in the nearby Barric gold mines and to the high populated fishing camps on Lake Victoria shorelines where firewood is the only source of energy for cooking and in part for fish curing. This increased consumption makes it one of the money earning wood-based products in the district. Firewood is sold to these camps at Tsh 2000.0 per headload. Increase in the market value of firewood in the basin of Lake Victoria is an opportunity for income generation through marketing of firewood. This can be sustained if local people are sensitized to plant and maintain individual woodlots of fast growing Acacia seyal. Unfortunately, the woodlands in the valleys of rivers Mori and Nyaburongo are public land with free access for grazing and for wood extraction. There are no guidelines or land tenure arrangements in place to regulate and control human activities in an area.

Another source of fuelwood in Rorya District that is gradually gaining popularity is charcoal. The estimates of charcoal marketed locally and across the border to Kenya are presented in Table 1. The counting was done at the fixed counting stations along the main roads to Musoma town, Tarime town and on the way to Kenya.

At least 27 plant species are exploited for charcoal whereas A. seyal is one of the most preferred due to good quality charcoal and their high stocking around the kilns. Extraction for charcoal was estimated as 358.84 tons/year. Wood biomass was estimated as 3.3 tons/ha. Up to 72.5 ha were being cleared annually for charcoal. About 113 charcoal makers were recorded each producing 111.8±12 bags of charcoal per annum. Selling price was Tsh. 5,500/bag. Hence the mean income per charcoal dealer was Tsh. 615,026/annum. The estimated round wood biomass of A. seyal of 3.3 tones/ha was comparable to findings by Malimbwi et al. (1994) in Kitulangalo forest reserve in Tanzania for other Acacia species as 3.99, 0.33, 3.8 and 032 tons/ha for Acacia nigrescens, Acacia usambarensis, Acacia nilotica and Acacia polyacantha, respectively. The area is losing 72.5 ha per year through charcoal burning alone. Since 1980s when the use of charcoal was intensified, an area approximately 60 km2 between Kowak and Chereche villages is already converted into typical grassland.

Before 1980s, A. seyal and A. robusta relatively constituted a close canopy within the study area especially in large part of Luo-imbo plains, Suba and Ingwe Divisions though at present, due to unsustainable utilization, they are depleted for charcoal making and brick burning by the defunct Kowak Co-bricks project. The current biomass is only 3.3.tons/ha that is comparatively low to 40.5 tons per ha as reported by Otieno (2000) in Miombo woodland in Babati District Tanzania. Currently the average DBH of Acacia spp in Nyaburongo valley is 7 to 8.8 cm that is equated to a DBH of samplings. Probably, another reason why deforested Acacia woodland may fail to regenerate in the woodlands of Rorya District is the continual decline in the seed bank. Trees in the area are cut young before the establishment of enough seeds reserve in the soil, then the sites remain bare long enough for seed reserves to diminish. Bergsten (1993) commented that even when a highly degraded soil stabilizes, it contains few seeds that may retard succession. Natural re-colonization of the trees in the affected area cannot be realized through tree seed because such seeds have disappeared from the soil (Lyaruu, 1995).

Timber/poles

Of all sampled Acacia species, mature A. robusta is the most preferred choice for construction poles. Lack of construction poles from other indigenous tree species has intensified exploitation of A. robusta as the closest alternative. The mature A. robusta are chosen for poles due to the ingrained resinous secretions that check termites and other insect borers. At present the species are totally clear felled from Nyaburongo valley. Unfortunately, according to local people, A. robusta does not coppice at maturity from either root suckers or stumps. Pole cutting causes adverse effect to the quality of forest because only trees of prime and straight stems are cut. According to Kajembe et al. (2004) this leads to lower quality of growing stock and depletion of the gene most used due to their abundance though less durable and borer-prone. A. seyal poles are used after local pre-treatment that is achieved by immersing green poles in ponds or rivers for at least 3 months. Within the period of 3 months the poles acquired considerable tensile strength and resistance against wood-borers. This skill is unique in that area and not reported previously.

Fully grown A. polyacantha in the study areas measure at least 30 cm DBH thus qualify them mainly for furniture, coffins and door tops. With modernization, dead relatives are buried in coffins instead of traditional hides/mats; office chairs are replacing cultural stools, cupboards instead of pots, wooden doors for woven withies etc.

Effect of rice farming on Acacia species

Black cotton soils are the ecological niche for both V. seyal and V. robusta. The same soils favor cultivation of rice. Rice farms were started in Nyaburongo and Mori valleys in 1990s. This has piloted clearing of vegetation (mainly Acacia seyal and A. robusta) around the farms to keep away bird pests (Quelea). Trees around rice farms attract pest-birds to alight on before raiding the crops. The surrounding trees and shrubs are cleared to up to 50 m from the edge of the farm on all sides as a way of pest control. Most of these cleared farms are abandoned in consecutive years in search for new sites in such a way that more areas of woodland are destroyed.

Logs

Bricks burning consume large quantity of logs mainly from A. seyal and A. robusta. These uses threatened plant diversity as they consume large trees that forms the top canopy of the habitats they are found. As a result, the removal of wood products from the natural ecosystems supersedes the rate of their recruitment. As more modern houses are built by using burnt bricks, more logs from A. seyal are consumed for bricks burning. Fortunately, the rate of A. seyal to regenerate is fast that can synchronize the drain.

Effect of free grazing to the Acacia woodlands

Conversion of Acacia woodlands to grasslands in the catchments of Rivers Mori and Nyaburongo may be irreversible unless some strict remedial measures are engaged. The area is cleared for charcoal and concurrently subjected to heavy grazing such that regeneration of Acacia saplings is affected. This is in accordance to Walter (1973) who claimed that vegetation change due to grazing may not be reversible in connection to “bush encroachment” which may take place as a result of heavy grazing. Pastoralism in the district is in a form of free grazing, and often, livestock keeping conflict with agriculture due to shrinking public land. Fodder trees of high canopy are cut by shepherds to be browsed by goats. Livestock keeping also involves cutting of thorny Acacia species for making of cattle sheds. Pastoralism leads to soil compaction around water sources especially of river Mori and its distributaries, gully erosion along grazing trails and overgrazing of some palatable species. The impact of grazing can be clearly seen in Nyancha, Suba and Luo-imbo Divisions where suitable pasture grasses such as Andropogon eucomus, Cynodon dactylon and Panicum maximum are overgrazed and have been replaced by unpalatable coarse grass such as Sporobolus natalensis and Enteropogon macrostachys. According to this study, the later species are indicators of reduced rangeland quality and equally, browsing of tree coppices worsens in dry months when palatable grasses are scarce. Chidumayo and Marunda (2010) comment that grasses and herbs alone cannot support a livestock industry in the semi-arid regions; browse, especially from Acacia species plays an essential part. Similar observation in Zimbabwe is reported by Hayward (2004) that in time of drought, when cereals and grass fails, Acacia trees provide fodder crops to livestock as well as a range of products for domestic and economic use.

Despite the intensified browsing in the Acacia woodlands, it is herewith established that the stumps of A. seyal can coppice and attain a height of 15 cm within 8 months. In this study however, the stumps that are exposed to an area of heavy grazing such that fresh coppices are browsed consistently, and do not grow enough to carry out photosynthesis, the roots starve and the stumps dry-up after a period of 3 to 5 years depending on the size of the stump. It was observed in this study that large stumps > 10 cm survived longer than 5 years, while small stumps <10 cm that were clear felled in the past five years were all dead. Timberlake et al. (2010) support that the ability to sprout takes advantage of the extensive root system and the substantial food storage in the remaining parts of the parent plant.

Overgrazing and clear felling of woodlands for charcoal is exhausting most rangelands in the study area, yet another challenge exist; funds accrued from charcoal are re-invested into more stocks of cattle and again grazed onto the same already deforested ecosystem. The outcome has been more destruction of pastures, low yield and frequent livestock diseases. Peasant’s life is characterized by overuse of land and vegetation accompanied by degradation due to lack of inputs. Poverty and hunger, which are common in peasant life, lead to environmental degradation, deterioration of agriculture and hence create more poverty and hunger (FAO, 1991). Livestock production is undoubtedly the most suitable industry for the utilization of the rangelands but full regard must be made for sustainability not exploitation (Chidumayo and Marunda, 2010).

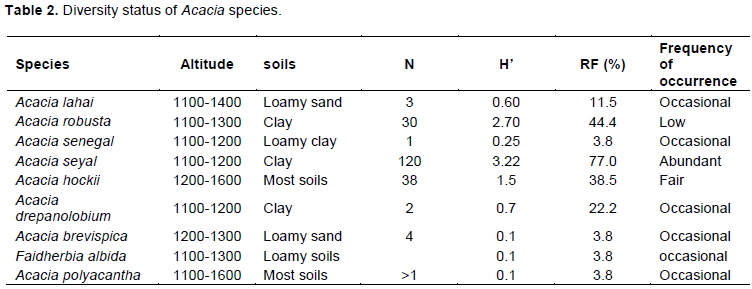

Diversity of Acacia species

The diversity and distribution status of Acacia species in Rorya district is presented in Table 2. Distribution and diversity trends of most recorded species in the study area do not coincide with findings in other studies in the region. With an exception of A. seyal, A. hockii, and A. robusta with 120, 38 and 30 number of stem/ha respectively, the rest of the recorded species have densities less than 4 stem/ha, and Shannon and Weaver Index (H) values below the average range of 1.5 to 4.5. This is because of their exceptionally low number of stem per hectare (Table 2). In a similar study within the same region in Serengeti ecosystem, Mligo (2015) estimated average H’ for woodland at 2.06 to 2.38. The stem density for most species in the study area are falling far short when compared to findings by Marshall et al., (2012) who estimated densities of East African Acacia in their diversity hotspots as 83, 60, 136, 28, 178, 46, 11.56 and 17 stems/ha for A. brevispica, A. drepanolobium, A. hockii, A. lahai, A, nilotica, A. robusta, A. Senegal, A. sieberiana, A. tortilis and A. xanthophloea, respectively. Basing on H’ values by Mligo (2015), it is implied that A. seyal in the study area (H’=3.2) is of fair diversity status. This is a strength supporting its inclusion in socio economic development programs. The densities of the rest of Acacia species are too low for immediate economic venture. Acacia hockii is tolerant to most soils and has moderate density, however it is a small shrub most appropriate for household fuel wood use. More Acacia species are sparsely distributed in the middle altitude from 1200 to 1400 m above sea level (asl) rich in sandy loam, neutral to alkaline pH. These neutral soils and higher altitudes are more supportive to agricultural crops. As a result natural vegetation including Acacia species are cleared to get more space for settlement and farms. Acacia species are not regarded with high esteem for conservation around the settlements. Marshall et al., (2012) also reported that many of the high Acacia diversity areas in East Africa have not previously been highlighted as of major importance for conservation of the genus. At lower altitudes between 1101 and 1200m asl (Table 2), A. seyal, A. robusta and A. drepanolobium dominated by being distributed in black cotton soils in Luo-imbo Division. These low altitudes are comparatively dry with average annual rainfall of 800 to 1000 mm that bears transitional features to semi desert vegetation. A. seyal is luckily performing best in these soil types that are less preferred for traditional food crops.

A. seyal is a potential source of income to about 20 villages in Rorya District if controlled extraction for charcoal is achieved. The species has good quality charcoal and can regenerate very fast to extractable Diameter at Breast Height (DBH) of 15-20 cm within 5 to 10 years. This is the growth rate of 3 cm per year. The growth rate of A. seyal in Nyaburongo and Mori valleys is superior to a report by Okello et al. (2006) that the majority of tree species have diameter increments ranging from 0.03 to 2.6 cm per annum. Acacia species regenerate fast naturally from soil seeds and from old stumps. Nevertheless, areas that are completely denuded of natural soil seed banks, planting can be initiated through imported seeds. Simple conservation guidelines and land tenure allocating monopoly to individuals will favor resilience of the woodland within 10 to 15 years. A. seyal species in this regard are a target species for their rapid biomass build-up and fast growth. Within a period of five years, retained Acacia species reaches an average diameter at breast height of 15 cm. This measure is sufficient for commercial charcoal making, poles and for firewood for sale to the available wood fuel markets. Major impending challenge is that Acacia woodlands in Nyaburongo and Mori valleys are public lands without a defined regulation on access. If nothing is done now to regress losses in the woodlands, then this precious resource will turn into bare woodlands for the ill fortune of rural communities who are dependent on it.

Rorya district is endowed with several Acacia species that are distributed unevenly due anthropogenic related activities. Of all, A. seyal is the most abundant with multiple ethnobotanical uses and obvious possibility for commercial extraction for charcoal. A. seyal accumulate wood biomass very fast than most imported species. The species can contribute not only to ecological stability but more on improved income of the households through selling of charcoal and firewood to the urban users under sustainable management. Acacia are able to colonize disturbed sites rapidly and act as natural repair kits on depleted soils (Hayward, 2004). Acacia therefore, offer great potential in areas of Africa where increasing population and livestock, together with series of drought have led to deforestation and severe land degradation (ibid). In a different scenario, this study recorded a positive local invention whereby the less durable Acacia species is pretreated to assume considerable strength for construction purposes. In addition, A. polyacantha previously considered less useful is now a potential source of timber for furniture and consequently is domesticated in home gardens or farms. Improved capacity of the Acacia woodlands in the valleys of Mori and Nyaburongo rely on re-addressing devastating forces in the area namely, free access for grazing, uncontrolled charcoal making, encroachment for farming and settlement. For immediate and permanent solution, responsible local governments must formulate guidelines and land tenure arrangements that grant sole ownership and user rights to individuals and dedicated social groups capable of managing demarcated land portions within the Acacia woodlands. The new guidelines will control charcoal burning and other human activities with adverse effect to the woodland ecosystems.