ABSTRACT

The present study was conducted to assess vascular plant diversity in a modified habitat in Shivalik region. Extensive surveys were conducted to document the species in each season and identification was done with the help of regional floras. A total of 191 species comprising 181 species of angiosperms (176 genera and 76 families), 2 species of pteridophytes (2 genera and 1 family), and 8 species of gymnosperms (7 genera and 5 families) were observed. The dominant Angiosperms families include Asteraceae (18 genera and 18 species), followed by Fabaceae (16 genera and 18 species), Lamiaceae (8 genera and 9 species), Solanaceae (5 genera and 9 species), Amaranthaceae (7 genera and 8 species), Euphorbiaceae (4 genera and 8 species) and Apocynaceae (6 genera and 7 species). In Gymnosperms, 5 families were recorded which include family Pinaceae, Cycadaceae, Zamiaceae, Araucariaceae and Cupressaceae. In pteridophytes, only two species of the family Pteridaceae were recorded. The categorizations on the basis of species habit, 96 species were recorded as herbs, 23 shrubs, 48 trees, 14 climbers, 8 grasses and 2 species of ferns. On the basis of species economic importance, 111 species had medicinal value, 43 ornamental, 8 medicinal-edible, 8 fodder, 7 edible, 2 medicinal-ornamental, 2 edible-fodder, 1 medicinal-timber, 1 fuel-fodder, 1 fuel-timber-edible-ornamental, 1 medicinal-fiber, 1 medicinal-fuel-fodder-religious, 1 ornamental-fuel, 1 ornamental-religious, 1 condiment uses while rests of the 2 species have other uses. In terms of occurrence, 36.64% species were native, while 63.35% species were non-native. The study provides baseline information on a modified habitat in an important eco-region and would be helpful in monitoring the changes in future.

Key words: Doon University, vascular plants, life form, nativity, exotic.

India is one of the 19 megabiodiverse countries of the world and consists of 48,158 species of plants (Anonymous, 2016) and 97,514 species of animals (Anonymous, 2016) in its ten biogeographic regions. The Shivalik or sub-Himalayan region is the youngest and ecologically fragile mountains have been categorized under the Indo-Gangetic plains with unique significance which integrates ecosystem of Indo-Malayan and palaearctic regions (Shivkumar et al., 2010). Shivalik Himalaya ranges over a stretch of 1500 miles long and 20 to 30 miles wide from the Indus to Brahmaputra in Assam (Kohli, 2002). In Uttarakhand State, the Shivalik Himalaya covers Tarai-Bhabhar, Shivalik and lesser Himalayan zones which include the part of district Pauri, Tehri, Dehradun and Haridwar, etc (Sharma et al., 2011).

Information on floral diversity of any region is a fundamental requirement to understand ecosystem type, biodiversity pattern and other ecological qualities pertaining to natural resource management and conservation planning at local, regional and global levels (Rajendran et al., 2014). Several studies have been conducted to understand vegetation diversity and pattern of Shivalik and its adjacent areas such as Upper Gangetic plains (Raizada, 1976), Chakrata, Dehradun and Saharanpur (Kanjilal, 1979), Mussoorie (Raizada and Saxena, 1984), Shimla (Collet, 1980), Garhwal Himalaya (Gaur, 1999; Sharma, 2013), Rajaji National Park (Singh and Anand, 2002), Dehradun (Adhikari, 2008, 2010) and Binog Wildlife Sanctuary (Kumar et al., 2012). Outstanding work on economically important plant species was also done by various workers (Nadkarni, 1910; Jain, 1968; Chauhan, 1999; Prajapati et al., 2003; Rawat and Vashistha, 2011).

Invasion of alien species has been considered a significant threat to an ecosytem which trigger the alteration of ecological characteristics of a habitat. Organisms immigrating to new habitats have been specified as alien, adventative, exotic, introduced and non-indigenous (Mack et al., 2000; McGeoch et al., 2010). Invasive species may occur through accidental, import for a limited purpose and subsequently escape or persistent introduction on a large scale (Ehrenfeld, 2003). These species affect natural ecosystem structure and function (Sekar et al., 2012), although have significant ecological benefits too. Alien species differ in their nutrient requirement, mode of resource utilization which cause changes in soil structure and profile (Negi and Hajra, 2007; Raizada et al., 2008). Invasion of exotic plant species might have significant adverse changes on the biodiversity and ecosystems functioning (Sharma and Raghubanshi, 2011) which further affect the environment as well as human health (Sekar, 2012). Over the years, invasion of various alien species of diverse origin has been increased in India and reported mainly from regions like Doon valley (Negi and Hajra, 2007), Kashmir Himalaya (Khuroo et al., 2007; Khuroo et al., 2010), Uttarakhand (Tewari et al., 2010), Uttar-Pradesh (Singh et al., 2010), Himachal-Pradesh (Jaryan et al., 2013), Assam (Das and Duarah, 2013), Jammu (Kaur et al., 2014), North-Eastern Uttar Pradesh (Srivastava et al., 2014), Karnataka (Kambhar and Kotresha, 2011), Madya-Pradesh (Wagh and Jain, 2015), Delhi (Mishra et al., 2015) and Haryana (Singh and Mohammed, 2015).

Over the years, as developmental activities are continuing to modify the natural ecosystem throughout the world, native floral and faunal species are continuously decreasing with their diminishing habitat. Therefore, it is important to document the current biodiversity status (diversity, life form, habitat, use values and phenological patterns) and monitor the changes in vegetation pattern over the time. Considering these facts, the present study has been conducted to assess plant diversity within the Doon University campus which would be important to monitor the change in near future and implementation of suitable management plan.

Study area

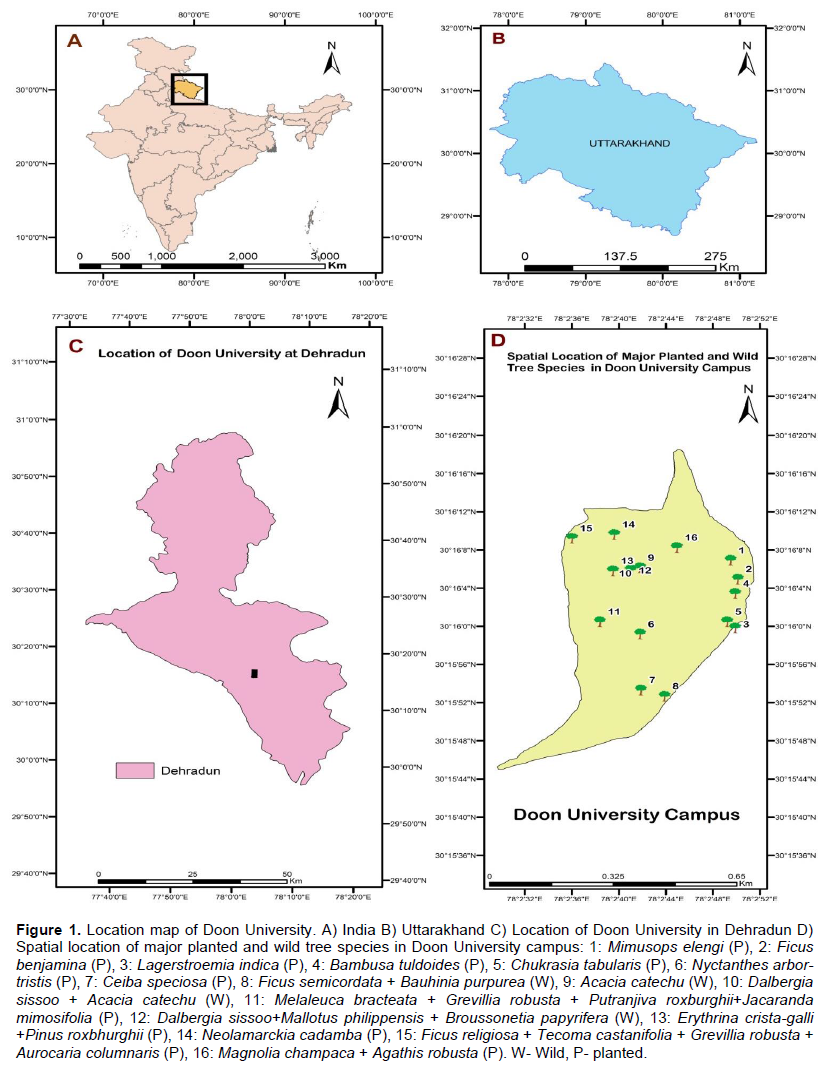

The present study was conducted in the Doon University campus, situated in the foot hills of Shivalik mountains, lying between 30°15'60''-30°16'10'' latitudes and 78°2'36''-78°2'50'' longitudes with an altitudinal range of 600 to 630 m asl and covering an area of approximately 0.199 km2 (Patwal and Naithani, 2014) (Figure 1). It is situated in a mosaic of various habitat types which includes thick deciduous forest, riverine habitat, agricultural fields and human settlements. Tectona grandis, Shorea robusta, Terminalia alata, Anogeissus latifolia, Mallotus phillippensis and Melia azedarach are major tree species in the forest. The riverine habitat is constituted by river Rispana which flows through eastern side of the campus and further join Song River, a tributary of the River Ganga. The average temperature remains moderate year round ranging from 35 to 40°C in the summers to 15 to 25°C in winter. The average annual rainfall recorded for the area is 2073 mm and most of the rainfall received during the month of June to September. Due to its unique location in the vicinity of different habitat types, the campus consist suitable environmental conditions to supports a variety of floral and faunal species.

Intensive plant surveys were conducted from August 2014 to December 2015 in different seasons, floral specimens were collected from different locations and identified with the help of relevant floras, book chapters and published literature (Raizada, 1976; Kanjilal, 1979; Raizada and Saxena, 1984; Collet, 1980; Gaur, 1999; Singh and Anand, 2002; Adhikari et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2011, 2013; Rajendran et al., 2014). For each species, information was collected on local name, altitudinal range, life form, flowering and fruiting periods. Information on economic importance and plant part used was collected through formal discussion with local people working as gardner and wage labour in the campus and from various earlier studies (Nadkarni, 1910; Prajapati et al., 2003; Kumar et al., 2012; Subramanion et al., 2013). In addition, information on ornamental flora was assembled from local plant nurseries and botanical gardens in Dehradun. Additional information such as updated nomenclature of native and exotic plant species was generated through related websites like international plant name index (IPNI, 2015), the plant list (2015), encyclopedia of life (EOL, 2015), tropicos (2016) and the global biodiversity information facility (GBIF, 2015). The nativity of the invasive plants has been recorded from published literatures (Champion and Seth, 1968; Negi and Hajra, 2007; Khuroo et al., 2007; Raizada et al., 2008; Reddy, 2008; Sharma and Raghubanshi, 2008; Weber et al., 2008; Khuroo et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2010; Tewari et al., 2010; Kambhar and Kotresha, 2011; Sekar et al., 2012; Sekar, 2012; Khuroo et al., 2012; Jaryan et al., 2013; Das and Duarah, 2013; Hiremath and Sundaram, 2013; Kaur et al., 2014; Srivastava et al., 2014; Wagh and Jain, 2015; Mishra et al., 2015; Singh and Mohammed, 2015) and further categorized according to their vernacular name, English name, altitudinal range, life forms (herb, shrub, trees, grass, climber and ferns), flowering fruiting periods, plant parts (leave, root, stems, rhizomes, bark, flowers, fruits, seeds and pods). Plants were further categorized according to their economic uses such as medicinal, ornamental, edible, timber, fuel, fodder, condiments and religious. Synonyms of plant species were not included to avoid the taxonomic inflation.

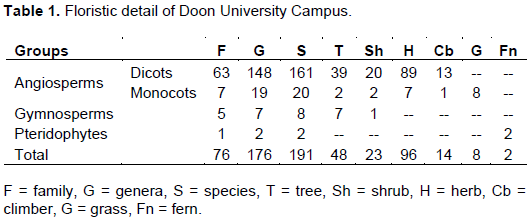

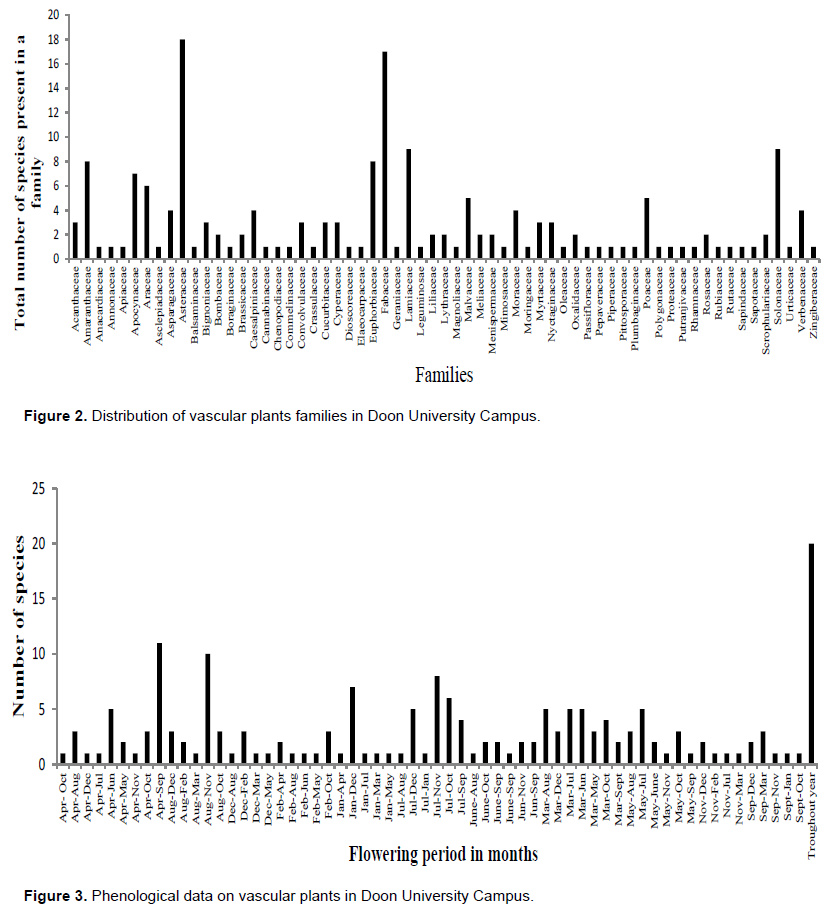

A total of 191 species of vascular plants (Angiosperms, Gymnosperms and Pteridophytes) belonging to 176 genera and 76 families were recorded within the campus. Among these species, 181 species were angiosperms including 161 species of dicotyledons and 20 species of monocotyledons (63 families and 148 genera), 8 gymnosperms and 2 pteridophytes. In terms of habit types, 48 tree species, 96 herb, 23 shrubs, 14 climbers, 8 grasses and rest of 2 species are belonging to ferns were recorded (Table 1). Family Asteraceae (18 genera, 18 species), Fabaceae (16 genera and 18 species), Lamiaceae (8 genera and 9 species), Solonaceae (5 genera and 9 species) were among the dominant families and are followed by Amaranthaceae (7 genera and 8 species), Euphorbiaceae (4 genera and 8 species), Apocynaceae (6 genera and 7 species), Araceae (5 genera and 5 species), Poaceae (5 genera and 5 species), Malvaceae (4 genera and 5 species) and Family Caesalpiniaceae, Verbenaceae, Moraceae, Asparagaceae (4 genera and 4 species in each families) are among the other (Figure 2). In gymnosperms, 8 species from 5 families (Pinaceae, Cycadaceae, Zamiaceae, Araucariaceae and Cupressaceae) were recorded, while 2 species of fern from family pteridaceae were recorded. Maximum flowering and fruiting period was observed in the plants throughout the year (20 species), followed by April to September (11 species), August to November (10 species), July to November (8 species), January to December (7 species), July to October (6 species), April to June (5 species), etc (Figure 3).

Economic importance of the species

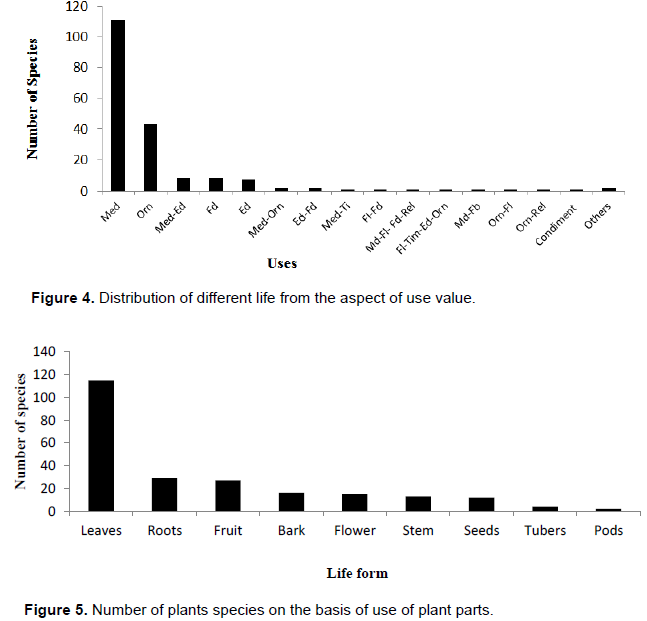

Out of the recorded 191 species, all species were found to be used for various economic purpose which includes 111 (58%) medicinal, 43 (23%) ornamental, 8 (4%) medicinal-edible, 8 (4%) fodder, 7 (4%) edible, 2 (1%) medicinal-ornamental, 2 (1%) edible-fodder, 1 (1%) medicinal-timber, 1 (1%) fuel-fodder, 1 (1%) fuel-timber-edible-ornamental, 1 (1%) medicinal-fiber, 1 (1%) medicinal-fuel-fodder-religious, 1 (1%) ornamental-fuel, 1 (1%) ornamental-religious, 1 (1%) condiment uses, while rests of the 2 (1%) species have other uses (Figure 4). In terms of part used for economical and ethno-botanical value, a total of 49% species leaves are used which is followed by root 12%, fruits 12%, bark 7%, seeds 5%, stem 6%, flower 6%, tubers 2% and of 1% pods (Figure 5).

Species of medicinal value

Most of the plant species recorded from the study site are highly medicinal in nature. Some important herbaceous medicinal plants from the study site are Acyranthus aspera L., Centella asiatica (L.) Urb., Calotropis procera (Aiton) Dryand., Dioscorea bulbifera L., Chamaesyce hirta L., Asperagus adscendens Buch.-Ham.ex Roxb.,

Erythrina suberosa Roxb., Ficus palmata Forssk., Moringa oleifera Lam., Mimusops elengi L., Nyctanthes arbor-tristis L., Chukrasia tabularis A. Juss., Mangifera indica L., Cassia fistula L., Phyllanthus emblica L., Elaeocarpus ganitrus (Roxb.) and Bauhinia purpurea (L.) Benth. are important medicinal plants.

Artemisia nilagrica (C.B.Clarke) Pamp., Acmella ciliata (Kunth) cass., Malvestrum coromendelianum (L.) Garcke, Cissampelos pereira L., Tinospora cordifolia (Thunb.) Miers, Boerhavia diffusa L., Plumbago zeylanica L., Oxalis latifolia Kunth, Murraya koenigii L. Sprengel, Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf. and Hellenia speciosa (J. Koenig) Govaerts. Among the woody plant species Ficus religiosa L., Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. ex DC.,

Nativity

Among the 191 recorded species, 70 (36.64%) are native, while 121 (63.35%) are non-natives or exotic species. Thus, the study reveals that the floristic diversity is dominated with exotic species and most of them are planted for ornamental purposes in the campus.

Native plant species

The native species diversity within the University campus are comparatively low. Among these species, Barleria cristata L., Cryptolepis dubia (Burm.f.) M.R. Almeida, Cynoglossum glochidiatum Wall. ex Benth., Bauhinia purpurea (L.) Benth., Cassia fistula L., Cycas rumphii Miq, Cyperus rotundus L., Phyllanthus emblica L., Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. ex DC., Desmodium concinnum DC., Erythrina suberosa Roxb., Crotalaria spectabilis Roth., Alysicarpus pubescens Y.W Law, Elaeocarpus serratus L., Leucas cephalotes (Roth) Spreng., Anisomeles indica (Linnaeus) Kuntze, Ajuga bracteosa Wall ex Benth., Perilla frutescens (L.), Asparagus adscendens Buch.-Ham.ex Roxb., Chukrasia tabularis A.Juss., Ficus palmata Forssk., Ficus religiosa L., Ficus sarmentosa Buch.-Ham. ex Sm., Moringa oleifera Lam., Nyctanthes arbor-tristis L., Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers., Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf., Putranjiva roxbhurghii Wall., Murraya Koenigii L. Sprengel, Mimusops elengi L., Clerodendrum infortunatum L. and Hellenia speciosa (J. Koenig) Govaerts are major native plants.

Invasive plants

Major exotic invasive species include Lantana camara L., Parthenium hysterophorus L., Ageratum conyzoides L., and Ricinus communis L. and are dominant throughout the campus. Species like Chenopodium album L., Bidens pilosa L., Amaranthus spinosus L., Synedrella nodiflora (L.) Gaertn., Galinsoga parviflora Cav., Sigesbeckia orientalis L., Tridax procumbens L., Xanthium strumarium L., Sonchus asper (L.) Hill., Argemone maxicana L., Impatiens balsamina L., Senna tora (L.) Roxb., Ipomoea quamoclit L., Cyperus iria L., Euphorbia heterophylla L., Chamaesyce hirta L., Mimosa pudica L., Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC., Sesbania bispinosa (Jacq.) W. Wight., Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit., Saccharum spontaneum L., Solanum nigrum L., Solanum viarum Dunal., Solanum torvum Sw., Vitex negundo L. were among the other naturally grown exotic species.

Exotic ornamental species

Among the recorded species, 63.35% species are non-natives or exotic. Some of these species are critical to native biodiversity and its ecological and socio-economic framework. Despite the fact, non-native or exotic species generally considered as noxious. However, they also play a significant role in ecological restoration, soil conservation and generating new socio-economic prospects. The field investigation revealed that exotic plants like Grevillea robusta A.Cunn. ex R.Br is used for its fuel wood and aesthetic value. Some other species like Vachellia nilotica (L.) P.J.H. Hurter & Mabb., Sesbania bispinosa (Jacq.) W. Wight, Pennisetum setaceum (Forssk.) Chiov and Trifolium resupinatum L. are used as fodder species. Tree species like Polyalthia longifolia (Sonn.) Thwaites, Plumeria obtusa L., Plumeria alba L., Hyophorbe lagenicaulis (L. H. Bailey) H. E. Moore., Agathis robusta (C. Mooreex F. Muell.) F. M. Bailey., Araucaria columnaris (G. Forst.) Hook., Jacaranda mimosifolia D. Don., Tecoma castanifolia (D. Don) Melch., Delonix regia (Bojer ex Hook.) Raf., Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco., Pongamia pinnata (L.) Pierre., Magnolia grandiflora L., Chukrasia tabularis A. Juss., Ficus benjamina L., Melaleuca bracteata F. Muell. and Zamia furfuracea L. F. in Aiton contributed to the aesthetic artistry of the university campus.

Origin of invasive species

A total of 11 geographic provinces were recorded in terms of species origin or nativity for the present study. The Tropical America contributed to the maximum percentage of species 61 (31.94%) followed by Asia (excluding Indian sub-continent) 20 (10.47%), Tropical Africa 12 (6.28%), Europe 10 (5.24%), Australia 7 (3.66%), Madagascar 5 (2.62), Eurasia 4 (2.09%),Mediteranean 2 (1.05%), Mascarene Islands 1 (0.52%), New Caledonia 1 (0.52%) and the West Indies 1 (0.52%). American continents have also contributed to majority of invasive species in other parts of India like Doon Valley and Uttarakhand (Negi and Hajra, 2007; Sekar et al., 2012), Indian Himalayan region (Sekar, 2012), Uttar Pradesh (Singh et al., 2010; Srivastava et al., 2014), Himachal Pradesh (Jaryan et al., 2013), Karnataka (Kambhar and Kotresha, 2011), Madhya Pradesh (Wagh and Jain, 2015), South Western Ghats (Aravindhan and Rajendran, 2014), Darjiling Himalaya (Moktan and Das, 2013), Tamil Nadu (Narasimhan and Arisdason, 2009).

The findings from literature and discussions with local inhabitants indicate that several invasive species are also used for various other purposes. For example, leaves of A. spinosus are edible and used as fodder while leaves and stem of G. parviflora are used for medicinal (anti-itch) as well as fodder purposes while Tagetes erecta is considered and used as religious plant species. A total of 67 species were reported to use for medicinal purposes by the local inhabitants and 42 exotic species planted for ornamental purposes within the campus. The economic uses of 3 species namely Barbarea vulgaris R.Br., Ipomoea triloba L. and Pteris vittata L. are not known (Table 2).

The vegetation pattern is crucial for the existence of various faunal species in any habitat. The unique floral diversity within the University campus provides suitable habitat to a number of wild faunal species including mammals (7), avifauna (138), reptiles (8), lepidopteron (41) and other insects (Balodi et al., unpublished). With the modification on the riverine habitat, nesting of species like Red-wattled lapwing Vanellus indicus has been affected and cutting of natural stand of Acacia catechue (L. f.) Willd. has affected nesting of Baya weaver Ploceus philippininus. However, one single A. catechue (L. f.) Willd tree holds one of the larget nesting colony (more than 150 nests from last two years) within the Doon Valley (Balodi et al., unpublished). The ornamental plant species like Hyophorbe lagenicaulis, Jacaranda mimosifolia D.Don., Bauhinia purpurea (L.) Benth.., Delonix regia (Bojer ex Hook.) Raf.., Vachellia nilotica (L.) P.J.H. Hurter & Mabb. Lagerstroemia indica (L.) Pers., Bombax ceiba L. Ceiba speciosa (A.St.-Hil.) Ravenna., Magnolia gradiflora L.., Grevillea robusta A. Cunn. ex R.Br.., Putranjiva roxbhurghii Wall., Neolamarckia cadamba (Roxb.) Bosser., Mimusops elengi L. and Zamia furfuracea L.F. in Aiton provide suitable nesting sites to various aviafaunal species like crows, Asian-pied sterling, kites and some other birds. Ornamental plant like P. orientalis (L.) Franco., is observed to be preferred by scaly-breasted munia Lonchura puctulata for its nesting. Various frugivorus birds’ species can be observed on many ornamental plant species during the fruiting season (Balodi et al., unpublished).

Bird community structure play vital roles in seed dispersal in human-alteredlandscapes(Pejchar et al., 2008) as birds are considered best dipersal agents. At a time when natural regeneration of native plant species experience challenges from climate change, land-use change, introduction of invasive species, birds play a vital role in dispersing seeds to suitable sites for regeneration (Gosper et al., 2005; Ruxton and Schaefer, 2012). However, seed dispersal of invasive species through avian communities in the important eco-regions like Shivalik could have adverse ecological consequences on the native flora.

The study provides baseline information on floristic diversity of a modified habitat from riverine and agricultural to concrete jungle and plantation in Shivalik landscape.Thesefindingwouldbeimportant in monitoring the changes in vegetation pattern in the near future. At present, the exotic floras dominate the native flora and are important in terms of influencing local environmental condition of the habitat. The flowering period of plants species of different origin would help in prediction of climate change over the years and role of interaction between local environmental conditions as well as their native behavior. Regular monitoring of vegetation and scientific inputs are crucial to promote native species and proper management of floristic diversity is crucial as they provide unique habitat to more than 138 bird species (used for perching, foraging, nesting, breeding, etc) and about 41 lepidopteron species. Further studies on their beneficial uses through phyto-chemical investigation would be important to conserve the important gene flow in a managed landscape to validate and sustain their ethno-medicinal importance.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

REFERENCES

|

Adhikari BS, Babu MM (2008). Floral diversity of Baanganga Wetland, Uttarakhand, India. Check List. 4(3):279-290.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Adhikari BS, Babu MM, Saklani PL, Rawat GS (2010). Medicinal plants diversity and their conservation status in Wildlife Institute of India (WII) campus, Dehradun. Ethnobotanical Leaflets. 14(1):46-83.

|

|

|

|

|

Anonymous (2016). Animal Discoveries: New species and new records, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata. pp.1-121.

|

|

|

|

|

Anonymous (2016). Plant Discoveries: New genera, species and new records, Botanical Survey of India, Kolkata. pp.1-128.

|

|

|

|

|

Aravindhan V, Rajendran A (2014). Diversity of Invasive Plant Species in Boluvampatti Forest Range, The Southern Western Ghats, India. Am. Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 14(8):724-731.

|

|

|

|

|

Champion HG, Seth SK (1968). A revised survey of the forest types of India, Natraj Publishers, Dehradun, India.

|

|

|

|

|

Chauhan NS (1999). Medicinal and Aromatic plants of Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi, India.

|

|

|

|

|

Collet H (1980). Flora Simlensis: A Handbook of the Flowering plants of Shimla and the Neighborhood. Bishan singh and Mahendra pal singh, Dehradun.

|

|

|

|

|

Das K, Duarah P (2013). Invasive alien plant species in the roadside areas of Jorhat, Assam: their harmful effects and beneficial uses. J Eng. Res. Appl. 3(5):353-358.

|

|

|

|

|

Ehrenfeld JG (2003). Effects of exotic plant invasions on soil nutrient cycling processes. Ecosystems. 6(6):503-523.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

EOL- Encyclopedia of life (2015). Free and open access to biodiversity data. http://www.eol.org. Accessed on 20 Oct 2015.

|

|

|

|

|

Gaur RD (1999). Flora of the District Garhwal, North West Himalaya. Transmedia. Srinagar.

|

|

|

|

|

GBIF - Global Biodiversity Information Facility (2015). Free and open access to biodiversity data. http://data.gbif.org/welcome.htm Accessed 15 January 2015.

|

|

|

|

|

Gosper CR, Stansbury CD, Vivian SG (2005). Seed dispersal of fleshy-fruited invasive plants by birds: contributing factors and management options. Diversity and Distribution. 11(6):549-558.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hiremath AJ, Sundaram B (2013). Invasive plant species in Indian protected areas: conserving biodiversity in cultural landscapes. In Plant Invasions in Protected Areas. Springer Netherlands. pp. 241-266.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

IPNI- The International plant name index (2015). Free and open access to biodiversity data. http://www.ipni.org. Accessed 17 Oct 2015.

|

|

|

|

|

Jain SK (1968). Medicinal plants. National Book Trust, New Delhi, India.

|

|

|

|

|

Jaryan V, Uniyal SK, Gupta RC, Singh RD (2013). Alien Flora of Indian Himalayan State of Himachal Pradesh. Environ.Monit. Assess. 185(7):6129-6153.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kambhar SV, Kotresha K (2011). A study on alien flora of Gadag District, Karnataka, India. Phytotaxa. 16(1):52-62

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kanjilal UN (1979). Forest flora of the Chakrata, Dehradun and Saharanpur forest divisions, United provinces. Bishan singh and Mahendra pal singh, Dehradun, India.

|

|

|

|

|

Kaur B, Kour R, Bhatia S, Sharma KK (2014). Diversity of invasive alien species of Jammu district (Jammu and Kashmir). Intern. J. Interdiscipl. Multidiscipl. Stud. 1(6):214-222.

|

|

|

|

|

Khuroo AA, Rashid I, Reshi Z, Dar GH, Wafai BA (2007). The alien flora of Kashmir Himalaya. Biol. Invasions 9(3):269-292.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Khuroo AA, Reshi ZA, Malik AH, Weber E, Rashid I, Dar GH (2012). Alien flora of India: taxonomic composition, invasion status and biogeographic affiliations. Biol. Invasions 14(1):99-113.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Khuroo AA, Weber E, Malik AH, Dar GH Reshi, ZA (2010). Taxonomic and biogeographic patterns in the native and alien woody flora of Kashmir Himalaya, India. Nord. J. Bot. 28(6):685-696.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kohli MS (2002). Mountains of India: Tourism, Adventure and Pilgrimage. Indus Publishing. P 21.

|

|

|

|

|

Kumar A, Mitra M, Singh G, Rawat G (2012). An inventory of the flora of Binog wildlife sanctuary, Mussoorie, Garhwal Himalaya. Indian J. Fundam. Appl. Life Sci. 2(1):281-299.

|

|

|

|

|

Mack RN, Simberloff D, Mark Lonsdale W, Evans H, Clout M, Bazzaz FA (2000). Biotic invasions: causes, epidemiology, global consequences, and control. Ecol. Appl. 10(3):689-710.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

McGeoch MA, Butchart SH, Spear D, Marais E, Kleynhans EJ, Symes A, Chanson J, Hoffmann M (2010). Global indicators of biological invasion: species numbers, biodiversity impact and policy responses. Divers. Distrib. 16(1):95-108.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mishra AK, Mir SA, Sharma MP, Singh, H (2015). Alien plant species in Delhi flora. Int. J. Geol. Earth Environ. Sci. 5(2):128-140.

|

|

|

|

|

Moktan S, Das AP (2013). Diversity and distribution of invasive alien plants along the altitudinal gradient in Darjiling Himalaya, India. Pleione. 7(2):305-313.

|

|

|

|

|

Nadkarni KM (1910). Indian plants and drugs with their medical properties and uses, Asiatic Publishing House, Delhi.

|

|

|

|

|

Negi PS, Hajra PK (2007). Alien flora of Doon Valley, Northwest Himalaya. Curr. Sci. 92(7):968-978.

|

|

|

|

|

Patwal PS, Naithani S (2014). Data base creation and analysis for rational planning. J. Stud. Dyn. Change 1(1):29-37.

|

|

|

|

|

Pejchar Liba, Pringle RM, Ranganathan J, Zook JR, Duran G, Oviedo F, Daily GC (2008). Birds as agents of seed dispersal in a human-dominated landscape in southern Costa Rica. Biol. Conserv. 141(2):536-544.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Prajapati ND, Purohit SS, Sharma AK, Kumar T (2003). A Handbook of Medicinal Plants: A complete source book. Agrobios (India).

|

|

|

|

|

Raizada MB, Saxena HO (1984). Flora of Mussoorie. Vol.1. Periodical expert Book Agency, Delhi.

|

|

|

|

|

Raizada P, Raghubanshi AS, Singh JS (2008). Impact of alien plant species on soil processes: A review. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biol. Sci. 78(4):288-298.

|

|

|

|

|

Raizada, MB (1976). Supplement to Duthe's Flora of the Upper Gangetic plain and the adjacent Siwalik and Sub-Himalayan Tracts. Bishan singh and Mahendra pal singh. International Book Distributors, Dehradun, India.

|

|

|

|

|

Rajendran A, Aravindhan V, Sarvalingam A (2014). Biodiversity of the Bharathiar university campus, India: A floristic approach. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 6(4):308-319.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rawat R, Vashistha, DP (2011). Common herbal plant in Uttarakhand, used in the popular medicinal preparation in Ayurveda. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 3(3):64-73.

|

|

|

|

|

Reddy CS (2008). Catalogue of invasive alien flora of India. Life Sci. J. 5(2):84-89.

|

|

|

|

|

Ruxton GD,Schaefer HM(2012. The conservation physiology of seed dispersal. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367(1596):1708-1718.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sekar KC (2012). Invasive alien plants of Indian Himalayan Region- Diversity and Implication. Am. J. Plant Sci. 3:177-184.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sekar KC, Manikandan R, Srivastava SK. (2012). Invasive alien plants of Uttarakhand Himalaya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 82(3):375-383.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sharma CM, Butola DS, Ghildiyal SK, Gairola S (2013). Phytodiversity along an altitudinal gradient in Dudhatoli forest of Garhwal Himalaya, Uttarakhand, India. Indian J. Med. Aromat. Plants 3(4):439-451.

|

|

|

|

|

Sharma GP, Raghubanshi AS (2011). Invasive Species: Ecology and Impact of Lantana camara. Invasive Alien Plants An Ecological Appraisal for the Indian Subcontinent. 1:19.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sharma J, Gaur RD, Painuli RM (2011). Conservation status and diversity of some important plants in the Shiwalik Himalaya of Uttarakhand, India. Indian J. Med. Aromat. Plants 1(2):75-82.

|

|

|

|

|

Singh A, Mohammed I (2015). Diversity of Invasive alien plant species in district Yamuna Nagar of Haryana, India. Biol. Forum. 7(2):1051-1056.

|

|

|

|

|

Singh K.P, Shukla AN, Singh JS (2010). State-level inventory of invasive alien plants, their source regions and use potential. Curr. Sci. 99(1):107-114.

|

|

|

|

|

Singh KK, P Anand (2002). Flora of Rajaji National Park, Uttaranchal. Bishan singh and Mahendra pal singh, Dehradun , India.

|

|

|

|

|

Sivakumar K, Sathyakumar S, Rawat GS (2010). A Preliminary review on conservation status of Shivalik landscape in Northwest, India. Indian Forester. 136(10):1376.

|

|

|

|

|

Srivastava S, Dvivedi A, Shukla RP (2014). Invasive alien species of terrestrial vegetation of North-Eastern Uttar Pradesh. Int. J. For. Res. 1-9.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Subramanion LJ, Siew YC, Dharmaraj S, Subramanian D, Lachimanan YL, Soundararajan V, Sreenivasan S (2013). Polyalthia longifolia Sonn: an Ancient remedy to explore for novel therapeutic agents. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 4(1):714-730.

|

|

|

|

|

Tewari LM, Jalal, JS, Kumar S, Pangtey YPS, Kumar R (2010). Wild and exotic gymnosperms of Uttarakhand, central Himalaya, India. Electronic J. Biol. Sci. 4:32-6.

|

|

|

|

|

The Plant List (2015). Free and open access website for updated names of plants. http://www.theplantlist.org. Accessed 17 Oct 2015.

|

|

|

|

|

Tropicos (2016). Free and open access to biodiversity data http://www.tropicos.org/. Accessed on 25 Dec 2015.

|

|

|

|

|

Wagh VV, Jain AK (2015). Invasive alien flora of Jhabua district, Madhya Pradesh, India. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 7(4):227-237.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Weber E, Sun SG, Li B (2008). Invasive alien plants in China: diversity and ecological insights. Biol. Invasions. 10(8):1411-1429.

Crossref

|

|