Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

Forest elephants play a vital role as keystone species in forest ecosystems, but little information is known on their feeding pattern which is a key concern for its conservation. This study was carried out in Nki National Park and the specific objective was to identify cultivated and non-cultivated plants eaten by elephants. Eleven 2 km line transects, and reconnaissance walk of approximately 40.16 km were used to identify all feeding signs of elephants. Also, administration of semi-structured questionnaires to 107 participants in 9 villages around the park was used to collect data on Human-Elephant Conflict mainly on crop raiding to identify cultivated plants eaten by elephants. Analysis was done using descriptive statistics in Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23. Results showed that 25 wild and 18 cultivated plants from 24 families were consumed by elephants in the park and along its peripheries with diet preference of fruits (62%) and least being stems (6%). The most abundantly consumed plant families were Poaceae (Setaria palmifolia), Sapotaceae (Gambeya lacourtiana), and least being Pandaceae (Panda oleosa) among other families. This shows that elephants have a very diverse diet requirement which is important in the management and conservation of this critically endangered species.

Key words: Feeding pattern, wild plants, cultivated plants, conservation, Loxodonta cyclotis.

INTRODUCTION

Population pressure, poverty, agricultural intensification and expansion, development of infrastructure, etc., have been marked as main threats to biodiversity in the tropics (Davidar et al., 2010; Bargali et al., 2018, 2019; Vibhuti et al., 2020; Padalia et al., 2022). Merely 7% of the earth's land surface is covered by tropical forests and harbour more than half of the world's species (Wilson, 1988) and are highly threatened by human activities (Htun et al., 2011; Baboo et al., 2017; Mourya et al., 2019). The aforementioned factors have reduced the natural resources for wild life and domestic life.

Forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis Matschie, 1900) consume all plants life forms and fruits make up a greater part of their diet with grass making a small proportion of their diet (Tchamba, 1996). Forest elephants rarely move far away from permanent drinking water, thus drinking water availability does not constrain their access to food resources, habitat selection, or long-distance movements (Powell, 1997). Forest elephants do not make large-scale migratory movements such as those exhibited in savannah elephants, this is confirmed by incipient data from telemetric studies (Powell, 1997), though, more recent telemetric studies showed that forest elephants may make movements of over 100 km when their range is not restricted by human activity. This is done using collars fitted with Global Positioning Systems (GPS).

Vegetation distribution and characteristics are important determinants of elephant density and distribution in African forests (Fay and Agnagna, 1991b; White, 1994a). Does drinking water availability drive the distribution and large-scale movements by forest elephants? Powell (1997) argued that the determinant of forest elephant distribution is brought about by ripe fruit availability and White (1994b) alluded that elephant may move as far as 50 km into the forest in search of super-abundant fruit patches. Forest elephants maintain a high fibre intake throughout the year consisting of leaf browse, wood, bark, roots, stems, and aquatic vegetation though fruit constitute a larger part of the diet, (White et al., 1993). Feeding ecology of African forest elephants precisely in Central Africa, has been less documented. Studies in Cameroon precisely in Santchou Forest Reserve (Tchamba and Seme, 1993), Bayang-Mbo and Korup forests (Powell, 1997) showed that different plant parts make up forest elephants’ diet which include leaves, bark, wood, roots, and fruit. Despite the unavailability of quantitative data, fruits, terrestrial herbaceous vegetation (THV) and secondary woody growth, all make up very important components of forest elephant diet, at least seasonally, and may influence elephant abundance and distribution (Short, 1983).

Forest elephants also occur at high density in open canopy, including secondary forests in Central Africa (Barnes et al., 1995a, b; Powell, 1997), where the abundance of forest floor vegetation may be higher than

the closed canopy forest types (Short, 1983; Barnes et al., 1991). The Marantaceae forest of the Lopé Reserve, Gabon has recorded the highest consistent density of forest elephants (3 individuals ha-1) (White, 1994b), where Terrestrial Herbaceous Vegetation (THV) (Rogers and Williamson, 1987) is more abundant as compared to the herb layer. As compared to the scrub forests of Kibale, the Lopé Marantaceae forest is also in the late stage of forest succession toward closed canopy or mature forest (White and Tutin, 2001). An abundant source of herbaceous browse may also be found in swamp forest (Barnes et al., 1991), as they do for savannah elephants in East Africa (Western and Lindsay, 1984). In addition to leafy vegetation, fruit availability may also influence the density and distribution of forest elephants (Short, 1983; Merz, 1986; White, 1994c; Powell, 1997).

Among some of the most important plants consumed by forest elephants are Anonidium mannii, Dudoscia species, Panda eleosa, Myrianthus arboreus, and Gambeya lacourtiana (Blake, 2002). The flora of Nki National Park was surveyed and found to consist of about 831 plant species belonging to 111 families (Nkonmeneck, 1998) but no study has been done in the park to ascertain the plants consumed by elephants which led to this study. A full knowledge of elephant foraging patterns is important for understanding their habitat requirements and for assessing their habitat condition for effective management. The primary objective of this study was to establish the different varieties of both wild and cultivated plant species consumed by elephants in the Nki National Park and its surroundings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of study area

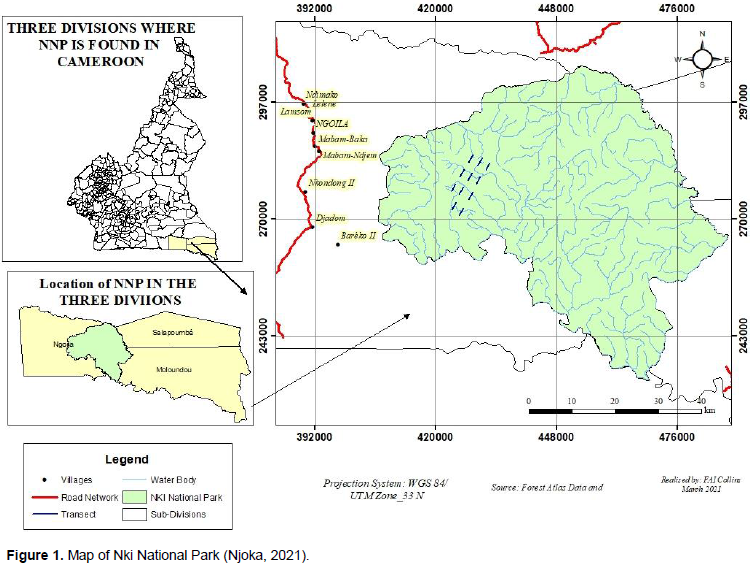

The Nki National Park (NNP) is situated between latitudes 2°05?N to 2°50?N and longitudes 14°05?E to 14°50?E. It covers a surface area of about 309,362 ha (3,093.62 km2) (Nyenty, 2016). It is situated in the East Region of Cameroon between Ngoyla sub-division in the Upper-Nyong division, Moloundou sub-division in the Boumba-and-Ngoko and Salapoumbé divisions (Figure 1).

Floristic results of the NNP revealed by Nkonmeneck (1998) and Ekobo (1998) showed the presence of 8 different types of vegetation disseminated in an evergreen, mixed and semi-deciduous forest. These include mono dominant forests of Gilbertiodendron dewevrei, mixed forests of G. dewevrei and Raphia regalis, forests dominated by R. regalis, forest clearings and swampy grasslands with or without salt licks, swampy forests of Raphia species, forests of Mapania species, forests of Baphia leptobotrys forests with undergrowth dominated by the family of Marantaceae. The wildlife of this region is estimated at 34 species of which large mammals are made of 11 species of primates, 12 species of ungulates and sub-ungulates including elephants and 4 species of carnivores (Ekobo, 1998).

Data collection

Data was collected in Ikwa area in the Nki National Park on eleven 2 km transect and approximately 40.16 km recce walkways and in nine villages surrounding the Nki National Park from the 18th of March to the 28th of May 2021. For this length of time, the research team went to the field twice collecting information on elephant feeding pattern. During surveys along the transects and approximately 40.16 km recce in between transects, all ‘fruit fall events’ of succulent fruits and pods observed along each transect and recce were recorded and identified to species where possible. Any fruit fall case was described as the fruit fall from a single plant seen on the survey route. Also, large trees, understory vegetation and vegetation on forest clearings eaten by elephants were identified.

Information on cultivated plant species eaten by elephants was collected by using semi-structured questionnaires/interviews (Bargali et al., 2007, 2009; Pandey et al., 2011; Parihaar et al., 2015; Padalia et al., 2017; Bisht et al., 2021) in nine selected villages. A total of 107 village informants were selected to get the required information for the study. Informants/Respondents were selected from the age of 16 and above and the questionnaire was based on elephant occupancy, detectability, and human-elephant conflict most especially on crop raiding to identify the cultivated plants consumed by elephants. Before the administration of questionnaires to the villagers, a pretesting was done in one of the villages (Doumzock) which was not included in the nine selected villages. This was to ensure that locals understand the questions. The nine selected villages were Dimako, Lelene, Lamson, Ngoyla-village, Mabam-Baka, Mabam-Ndjem, Nkondong II, Djadom and Bareko II.

Plant identification

Plant identification was done in the field using morphological characters. Plant samples, videos and images of plant characters were recorded for later identification by Mr. Belinga Bana Jean Paul (botanist at WWF-Jengi Tridom in Ngoyla) and an inventory of these plants was made.

Data analysis

Inventory was made of the collected and identified plants showing their families, species and the part of the plant consumed by elephants. These plants were also grouped into monocots and dicots and descriptive statistics were used to compare various variables using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 23 and the results presented in three tables and four figures.

RESULTS

Species of plants eaten by elephants in the Nki National Park and its peripheries

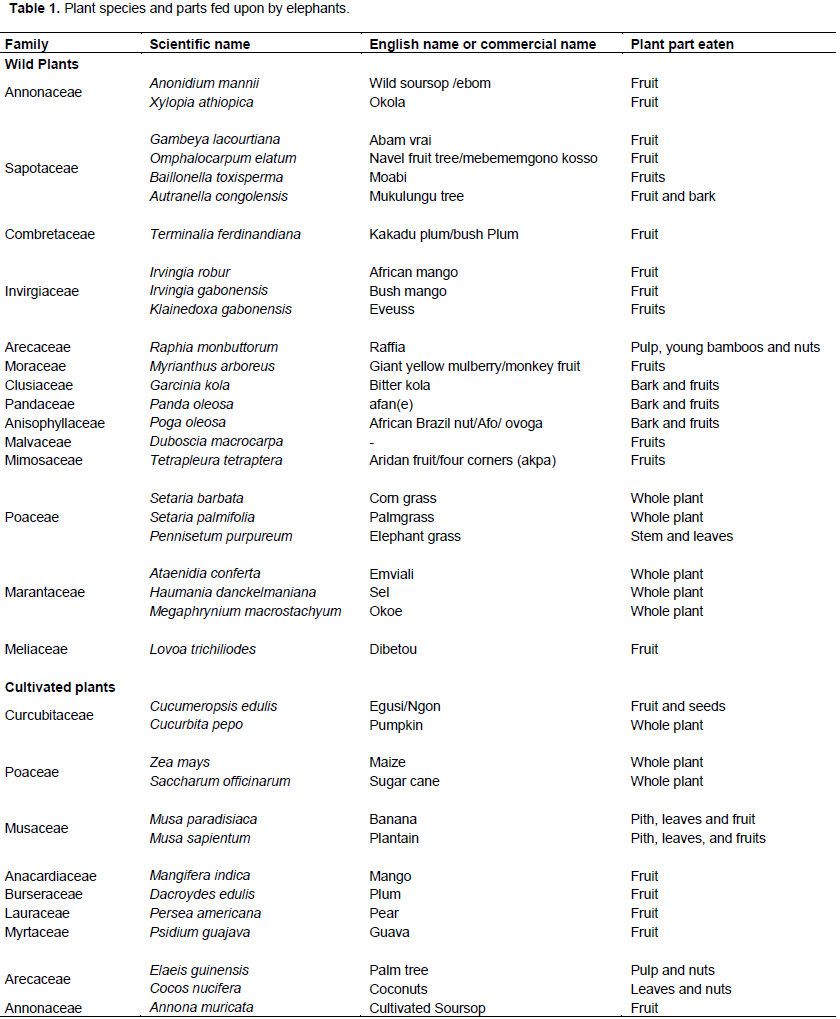

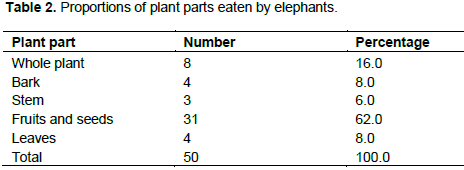

During the survey on transects, recces and interviews, several species of wild and cultivated plants were recorded. 25 wild plants and 18 cultivated plants were identified to be fed upon by elephants in the Nki National Park. These plants were grouped into 24 families with different plant parts consumed: leaves, stems, bark, fruits, seeds, and pulp (Table 1).

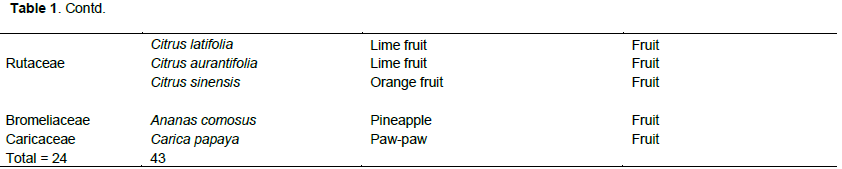

Plant parts consumed by elephants

The identified plants species were grouped according to the different parts consumed by elephants; fruits and seeds, leaves, stems, bark, and whole plant (Table 2). From the identified plants eaten by elephants, the highest proportion of the plant part eaten were fruits and seeds (62%) and the least was stem (6.0%).

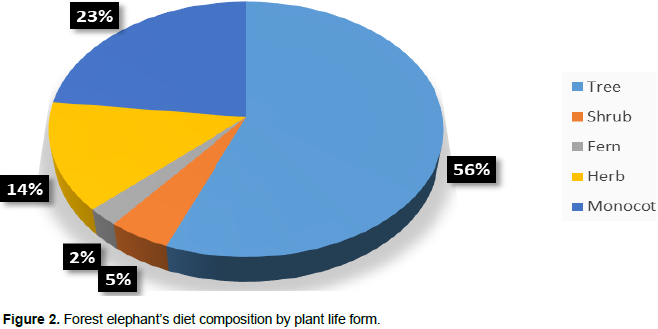

Forest elephant’s diet composition by life form

Elephants fed more on trees which accounted for 56% of their food from plant life form, followed by monocotyledons with 23% of species and the least was fern with 2% (Figure 2).

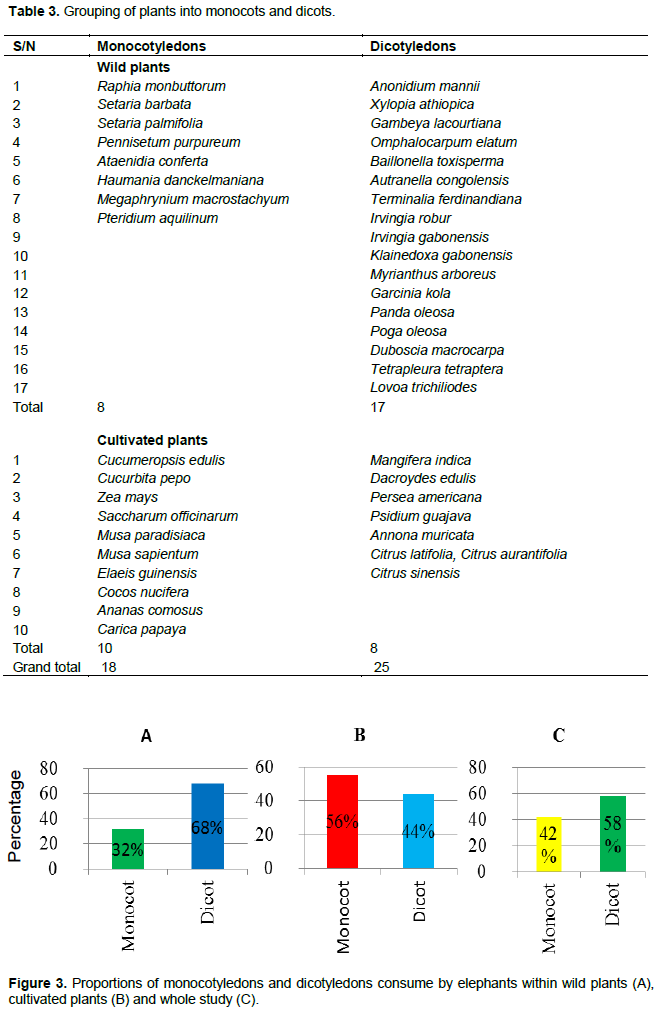

Monocotyledons and dicotyledons’ percentage consumption by elephant

Plant species eaten by elephants were grouped into monocotyledons and dicotyledons for both wild and cultivated plant species and for the entire plant species collected (Table 3). Among the wild plants collected, 68.0% were dicots while 32.0% were monocots. Cultivated plants showed 44% dicots and 56% monocots but overall, 58% dicots and 42% monocots plants are consumed by elephants (Figure 3).

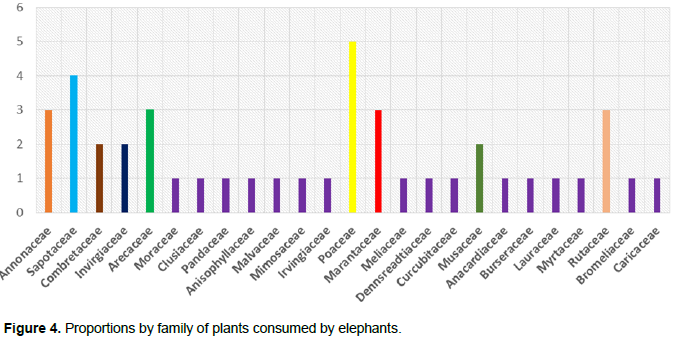

Plant species eaten by elephants classified according to family

The different plant species eaten by elephants were classified according to families to identify which family had the highest number of species eaten by elephants (Figure 4). Many families had the same number of plants that were consumed by elephants. Poaceae was the family with the most abundant plant species consumed by elephants, followed by Sapotaceae and lastly by Pandaceae among many other families. Many families had the same number of plants that were consumed by elephants.

DISCUSSION

The flora of Nki National Park is diverse with about 831 plant species belonging to 111 families of which 544 are in the undergrowth and 287 have diameters greater than or equal to 10 cm (Nkonmeneck, 1998). Of this great diversity, this study recorded only 25 wild plants in the park and 18 cultivated plants along the peripheries of the park known to be eaten by elephants in this park. In the Santchou reserve, Tchamba and Seme (1993) identified only 39 plant species consumed by forest elephants out of which 17 were fruits. Blake (2002) recorded 351 different plant species from 73 families in Ndoki National Park. The comparatively large food list for elephants in the Ndoki National Park may have more to do with the focus and long duration of the study and not a difference in the forest elephant diet.

It is ascertained that forest elephants consume more fruits compared to savannah elephants (Alexandre, 1978; Gautier-Hion et al., 1985; Dudley et al., 1992; Tchamba and Seme, 1993; White et al., 1993; Feer, 1995; Powell, 1997). This study indicated that fruits accounted for the highest proportion (62%) of plant part consumed by elephants. This aligns with an extensive study on the role of forest elephants as seed dispersers in Bayang-Mbo and Korup forests Cameroon (Powell, 1997) who isolated 93 different species of germinating seedlings in elephant dung piles. This was further confirmed by the study of Blake (2002) in the Ndoki National Park where elephants consumed a minimum of 96 species of fruit from 35 families, and fruit was present in 94.4% of dung piles.

Overall, trees mostly dicots (58%) were the most heavily consumed plant life form. Grass was rarely eaten by elephants in the forest though the most abundant plant family (Poaceae) recorded were grasses, but their consumption rate was low. This same pattern was reported by Blake (2002) in the Ndoki National Park in neighboring Congo where forest elephants fed mostly on tree products than grasses. Information on food selection of forest elephants by life form is limited. Tchamba and Seme (1993) reported that in the Santchou reserve, elephants feed mostly by either grazing or stripping off fruit' which constituted 45 and 38% of their records, while only 6% of feeding observations were recorded of elephants eating leaves and twigs. The Santchou reserve has many vegetation types; savannah, swamp forest and farmland, and forest elephant rates of feeding may vary by vegetation type and these data may not reflect overall life form selection rates of elephants. Other published studies of forest elephant feeding ecology give no information on the relative frequency with which the different plant life forms are eaten but rather species lists by life form is used as an indicator of the importance of each plant species (Merz, 1981; Short, 1981; White et al., 1993). All these studies show that, in terms of number of species, small dicotyledonous trees are the most commonly eaten plant type. This present study shows 68% dicots and 32% monocots consumption of wild plants, a 56%:44% monocots and dicots consumption pattern of cultivated crops along the peripheries of the park and an overall 58% dicots and 42% monocots consumption rate of all identified plant species. Based on plant life forms, this study showed that trees (57%) were the most consumed, then monocots (23%), herbs (14%), shrubs (4%) and least consumed was ferns (2%). An abundant monocotyledon remains (excluding grasses) in dung samples was found throughout the year in the Lopé Reserve (White et al., 1993), though neither Merz (1981) nor Short (1981) listed a single monocotyledon food species in their study sites, even though these species were present in the understory.

Across all plant life forms, fruits and seeds constituted 62% of all feeding events, though when elephants find themselves on cultivated land, most crops are consumed whole. Other studies have not focused on identifying the different cultivated plant species raided by elephants where human-elephant conflict is prevalent. This study identified 18 species of cultivated plants consumed by elephants on farmlands.

This study recorded Poaceae as the family with the most abundant plant species consumed by forest elephants though their proportion of consumption was very small. The Nki National Park is made of different vegetation types, and since feeding ecology of elephant is influenced by habitat type, grasses may compensate for low fruit availability in some habitat types or during seasonal decrease in fruit availability.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study showed that forest elephants feed on a diverse diet of different plant species consisting of 25 wild plants and 18 cultivated plants with their diet preference mainly consisting of fruits in the Nki National Park and its surroundings. This knowledge on elephant feeding requirements is essential for the conservation of this Critically Endangered Species. Plant species such as A. mannii, G. lacourtiana, Duboscia macrocarpa, Irvingia gabonensis and Baillonella toxisperma among many others which are consumed maximally by elephants should be propagated/regenerated and managed in-situ at higher level/quantity so that elephants could not face any paucity of the food.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Jana Robeyst Trust Fund for funding this study and Ideawild for donating equipment used in this study. Special thanks to the conservator of Nki National Park for granting the authors permission to carry out this research in the park. Gratitude to the field coordinators Fondja Calvin, Belinga Bana Jean Paul and all ecoguards for guidance through data collection.

REFERENCES

|

Alexandre DY (1978). Le role disseminateur des elephants enforêt de Tai, (Côte d'Ivoire). La Terre et Vie 32:47-72. |

|

|

Baboo B, SagarR, Bargali SS, HariomVerma (2017). Tree species composition, regeneration and diversity within the protected area of Indian dry tropical forest. Tropical Ecology 58(3):409-423. |

|

|

Bargali K, Manral V, Padalia K, Bargali SS, Upadhyay VP (2018) Effect of vegetation type and season on microbial biomass carbon in Central Himalayan Forest soils, India. Catena 171:125-135. |

|

|

Bargali SS, Padalia K, Bargali K (2019) Effects of tree fostering on soil health and microbial biomass under different land use systems in Central Himalaya. Land Degradation and Development 30:1984-1998. |

|

|

Bargali SS, Pandey K, Lalji Singh, Shrivastava SK (2009). Participation of rural women in rice based agroecosystem. International Rice Research Notes 33(1):1-2. |

|

|

Bargali SS, Singh SP, Shrivastava SK, Kolhe SS (2007). Forestry plantations on rice bunds: Farmers' perceptions and technology adoption. International Rice Research Notes 32(2):40-41. |

|

|

Barnes RFW, Blom A, Alers MPT, Barnes KL (1995b). An estimate of the numbers of forest elephants in Gabon. Journal of Tropical Ecology 11:27-37. |

|

|

Barnes RFW, Blom A, Alers MPT (1995a). A review of the status of forest elephants (Loxodonta africana cyclotis) in central Africa. Biological Conservation 71:125-132. |

|

|

Barnes RFW, Barnes K, Alers M, Blom A (1991). Man determines the distribution of elephants in the rain forests of northeastern Gabon. African Journal of Ecology. 29:54-63. |

|

|

Bisht V, Padalia K, Bargali SS, Bargali K (2021). Structure and energy efficiency of Agroforestry systems practiced by tribal community in Central Himalayas. Vegetos 34:368-383. |

|

|

Blake S (2002). The ecology of forest elephant distribution and its implications for conservation [PhD]. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh. 319. |

|

|

Davidar P, Sahoo S, Mammen PC, Acharya P, Puyravaud JP, Arjunan M, Garrigues JP, Roessingh K (2010). Assessing the extent and causes of forest degradation in India: Where do we stand? Biological Conservation 143:2937-2944. |

|

|

Dudley JP, Mensah-Ntiamoah AY, Kpelle DG (1992). Forest elephants in a rainforest fragment: preliminary findings from a wildlife conservation project in southern Ghana. African Journal of Ecology 30:116-126. |

|

|

Ekobo A (1998). Large mammals and vegetation surveys in the Boumba-Bek and Nki project area. WWF Cameroon internal report, 63pp. + annexes. |

|

|

Fay JM, Agnagna M (1991b). A population survey of forest elephants (Loxodonta africana cyclotis) in Northern Congo. African Journal of Ecology 29:177-187. |

|

|

Feer F (1995). Morphology of fruits dispersed by African forest elephants. African Journal of Ecology 33:279-284. |

|

|

Gautier-Hion A, Duplantier JM, Quris R, Feer F, Sourd C, Decoux JP, Dubost G, Emmons L H, Erard C, Hecketsweiler P, Moungazi A, Roussilhon C, Thiollay JM (1985). Fruit characters as a basis of fruit choice and seed dispersal in a tropical forest community. Oecologia 65:324-337. |

|

|

Htun NZ, Mizoue N, Yoshida S (2011). Tree species composition and diversity at different levels of disturbance in Popa Mountain Park, Myanmar. Biotropica 43:597-603. |

|

|

Merz G (1981). Recherche sur la biologie de nutrition et les habitats préférés de l'eléphant de forêt. Mammalia 45:299-312. |

|

|

Merz G (1986). Movement patterns and group size of the African forest elephant (Loxodonta africana cyclotis) in the Tai National Park, Ivory Coast. African Journal of Ecology 24:133-136. |

|

|

Mourya NR, Bargali K, Bargali SS (2019). Effect of Coriarian epalensis Wall. Colonization in a mixed conifer forest of Indian Central Himalaya. Journal of Forestry 30(1):305-317. |

|

|

Nkonmeneck P (1998). Les Populations des Zones Forestières Africaines et les projets de Conservation des ecosystems et les resources naturelles: exemple du Cameroon. Com.propos.au sém. FORAFRI, Libreville. |

|

|

Nyenty FA (2016). Survey of large and medium sized mammals in Ikwa bai-Nki National Park. Acadamiaedu. |

|

|

Padalia K, Bargali SS, Bargali K, Vijyeta Manral (2022). Soil microbial biomass phosphorus under different land use systems. Tropical Ecology. |

|

|

Padalia K, Bargali K, Bargali SS (2017). Present scenario of agriculture and its allied occupation in a typical hill village of Central Himalaya, India. Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 87(1):132-141. |

|

|

Pandey K, Bargali SS, Kolhe SS (2011). Adoption of technology by rural women in rice based agroecosystem. International Rice Research Notes 36:1-4. |

|

|

Parihaar RS, Bargali K, Bargali SS (2015). Status of an indigenous agroforestry system: a case study in Kumaun Himalaya, India. Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 85(3):442-447. |

|

|

Powell J (1997). The Ecology of Forest Elephants (Loxodonta africana cyclotis Matschie 1900) in Banyang-Mbo and Korup Forests, Cameroon with Particular Reference to their Role as Seed Dispersal Agents. Ph. D. Thesis. University of Cambridge, Cambridge. |

|

|

Rogers ME, Williamson EA (1987). Density of herbaceous plants eaten by gorillas in Gabon: some preliminary data. Biotropica 19:278-281. |

|

|

Short J (1981). Diet and feeding behaviour of the forest elephant. Mammalia 45:177-185. |

|

|

Short J (1983). Density and seasonal movements of forest elephant (Loxodonta africana cyclotis) in Bia National Park, Ghana. African Journal of Ecology 21:175-184. |

|

|

Tchamba M (1996). History and present status of the human/elephant conflict in the Waza Logone region, Cameroon, West Africa. Biological Conservation 75:35-41. |

|

|

Tchamba MN, Seme PM (1993). Diet and feeding behavior of the forest elephant in the Santchou Reserve, Cameroon. African Journal of Ecology 31:165-171. |

|

|

Vibhuti, Bargali K, Bargali SS (2020). Effect of size and altitude on soil organic carbon stock in homegarden agroforestry system in Central Himalaya, India. Acta Ecologica Sinica 40(6):483-491. |

|

|

Western D, Lindsay WK (1984). Seasonal herd dynamics of a savannah elephant population. African Journal of Ecology 22:229-244. |

|

|

White LJT (1994a). Factors affecting the duration of elephant dung piles in rain forest in the Lope' Reserve, Gabon. African Journal of Ecology 33: 142-150. |

|

|

White LJT (1994c). Sacoglottis gabonensis fruiting and the seasonal movement of elephants in the Lopé Reserve, Gabon. Journal of Tropical Ecology 10:121-125. |

|

|

White LJT (1994b). The effects of commercial mechanised logging on forest structure and composition on a transect in the Lopé Reserve. Journal of Tropical Ecology 10:309-318. |

|

|

White LJT, Tutin CEG (2001). Why chimpanzees and gorillas respond differently to logging: A cautionary tale from Gabon. in Weber LJT, White A, Vedder and L Naughton-Treves editor. African Rain Forest Ecology and Conservation. Yale University Press, New Haven. |

|

|

White LJT, Tutin CEG, Fernandez M (1993). Group composition and diet of forest elephants, Loxodonta africana cyclotis, Matschie 1900, in the Lopé Reserve, Gabon. African Journal of Ecology 31:181-199. |

|

|

Wilson EO (1988). The current state of biological diversity. pp. 3-18. In: Wilson EO, Peter FM (eds.) Biodiversity. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, USA. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0