ABSTRACT

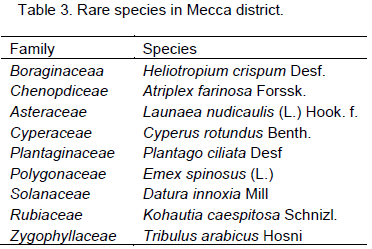

The flora of Mecca city district, Saudi Arabia has been recently studied between March and July, 2014. Four hundred and thirty three (433) specimens were collected from the study area. The specimens were found to belong to forty four (44) families, one hundred twenty five (125) genera and one hundred and eighty four (184) species. In this work and for the first time, four new species (unidentified, possibly new) were collected with specimen’s numbers: 40, 175, 279 and 415. Besides, the study came out with nine rare species to the flora of Saudi Arabia: Tribulus arabicus Atriplex farinosa, Cyperus rotundus, Datura innoxia, Emex spinosus, Heliotropium crispum, Kohautia caespitosa, Launaea nudicaulis and Plantago ciliata. It was found that the largest family in Mecca is Poaceae represented by 17% followed by Fabaceae with a percentage of 13%. The most prevalent species was Calotropis procera. From the analysis of species, the most chorotype prevalent was Saharo-Arabian with 27.70%. In addition, the most life-forms prevalent is the Therophytes with 41%. On the other hand, most of the species of high percentage 24.57% are used for medicinal purpose.

Key words: Flora, mecca, Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia represents almost 80% of the Arabian Peninsula with an area of about 2.25 million km2 (Almazroui et al., 2012). It extends between latitude 16’ 83? N 32’43? N and longitude 34’ 36? E 56?E (Meelad, 2006; Al-Amri, 2007). It is an important source of biodiversity and contains about 2250 species. Moreover, the number of species increased from approximately 1500 to almost 2300 (Alfarhan et al., 2005; Masrahi et al., 2012).

Overall, the most dominant families are Fabaceae and Poaceae due to arid and extreme arid climate adaptation (Chaudhary, 1989). The vegetation cover in the area is xerophytic (El-Ghanim et al., 2010).

Alshareef, (1984) reported that Mecca is located in Wadis between the mountainous region of the west of Saudi Arabia. Moreover, it is located in a fragile system (Abdel Khalik et al., 2013). More specifically, the tempera-ture in Mecca ranges between 40-49°C (Ashrae, 2005). The rate of rainfall ranges between 50-80 mm / year and most of precipitation is in winter that causes reduced vegetative cover.

The study area is a rangeland in Western of Saudi Arabia along with the coast of Red Sea, including major rangeland sites in Mecca Province (Daur, 2012).

Broadly, Mecca is specialized by different types of plants and great species diversity(Al-Said, 1993; Rahman et al., 2004).

Apparently, so many species have been playing a vital part of healthcare since the past days to the present day (Sher and Aldosari, 2013), for example, some of the flora elements are beneficial to human being used in folk medicine in the past (El-Ghazali et al., 2010). In addition, El-Ghazali and Al-Soqeer (2013) believed that other flora elemnts can cause a lot of losses in crops such as weeds flora. Besides, Luramiaceae medicinal plants are most abundant in Saudi Arabia (Rahman et al., 2004).

Fundamentally, the interesting fact about Mecca is the overlapping with Hail, based on its loacation as being in a wadi between two mountain ranges Aja and Salma. The major types of plants in wadi Rimah-Hail region are Acacia and some of Senna (Al-Turki and Al-Olayan, 2003).

The flora of Saudi Arabia has been extensively studied (Zohary, 1957); the most important studies is given by Mighaid (1974) 'Flora of Saudia Arabia' and published for four times, the last edition was published in 1996. Furthermore, three volumes about 'Flora of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Illustrated' was written by Chaudhary (1999, 2000, 2001). Moreover, a book was written by Chaudhary and Al-Jowaid (1999, 2013) titled Vegetation of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as published for two times. Large number of articles have discussed this topic such as Contribution to the Flora of Saudi Arabia: Hail Region by Al-Turki and Al-Olayan (2003), A floristic account on Raudhat Khraim Central province, Saudi Arabia by Alfarhan (2011) and Diversity Of Perennial Plants At Ibex Reserve In Saudi Arabia by Al-Khamis et al. (2012).

The main objectives of this study were collecting and identifying of the flowering plants species in Mecca, mapping the geographical distribution of the recorded species based on GIS recording and analysis of the flora components.

Study area

In April 2014, a floristic survey was carried out in Mecca Province. Mecca is located in western part of Saudi Arabia and western Arabian Peninsula. In particular, it is in the valley area between Hijaz mountain at the intersection of degree latitudes 27/19 N longitude 40/39 E, about 80 km from Jeddah on the Red Sea coast (Figure 1). Mecca is bound by Al-Gamom on the north, Al- Lith in the south, Taif in the east and the Red Sea coast and Jeddah in the west. In addition, it is characterised by high temperature ranges between 40-49°C, low rain fall (50-80 mm/year), high light intensity

and low humidity (Al- Khalif et al., 1430). Moreover, it consists of several regions (Arafat, Mina, Muzdalifah, Mount Thour, Mount Alnoor, Kuday, Al-Zahir, Al-Utaibiyyah, Al-Nuzha, Alzama, Al-Sharaai (Mount Tashbeer), Valley Numan, Al-Maabdah and Al-Abdeeah) (Figures 1 and 2).

Some of those regions are valleys below 250 m and others are mountainous areas above 700 m. Besides, Mecca contains very solid granitic rocks, as well as, it rises above the sea level about 330 m (Figures 3 and 4). Thus, the heights in Mecca ranges from 250-700 m with the most common height of about 330 or 350 m.

Survey procedure

To cover and satisfy the research objectives as well as to gather the needed information, two trips to Saudi Arabia (Mecca) were conducted. The first trip was conducted during the growing season at the beginning of April, 2014 and consisted of 48 localities as showed in the study area. Furthermore, localities were recorded by determining the locations using Global Positioning System (GPS).

Plant material

Tools used for collection

The data were collected through samples taken from daily field trips during April as it was representing in forty-eight sites were determined using (GPS). The samples were collected using secateurs to cut plant parts and then put them in various sizes of plastic bags. Moreover, duplicates for each sample were taken depending on plant availability. Pictures using camera (Nikon D3100) for each plant samples was taken.

By the end of the field trip, these samples were taken to the herbarium at The University of Jordan, Department of Biological Sciences, Amman-Jordan (AMM) for poisoning mounting, identifying and preservation as herbarium specimens.

Preparation of plant specimens

Several steps were used to prepare the plant specimens.

Collection

The collecting of specimens was done by random stops in various areas of Mecca region depending on the existence of the plants. Then the collected plants were put in plastic bags with numeric numbers mentioned in the Table 1.

Pressing and drying

The collected material of plant specimens were pressed using wooden board presses, old newspaper, drying paper and filter paper to drying the specimens, every day filter paper were changed for a week up to ten days until specimens were dried.

Poisoning

A mixture of 150 g of mercuric chloride (HgCl2) and 350 g of ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) was dissolved in as little needed water as possible until the solution had no residue and became trans-parent. The solution was prepared using automating stirrer. Then the solution was added to 10 L of commercial alcohol (96% ethanol) and used for every specimen.

Filling

Arrangement and insersion of collected specimen to the herbarium, Department of Biological Science, Faculty of Science, The University of Jordan (AMM) was done.

Method of identification

Basically, the collected plant specimens were identified and named by Prof. Al-Eisawi, using references for Flora of Saudi Arabia, Flora Palaestine and Flora of Egypt (Bouls, 1999-2005; Chaudhary, 1989; Chaudhary, 1999-2001; Chaudhary and Al-Jowaid, 1999; Chaudhary and Zawawi, 1983; Feinburn-Dothan, 1978 and 1986; Migahid, 1978 and 1988; Migahid and Hammouda, 1974; Migahid et al., 1977; Zohary, 1966, 1972).

Species life-forms were determined according to the location of regenerative buds and the parts shed during the unfavorable season (Raunkier, 1934). A chronological analysis of the floristic categories of species was made to assign the recorded species to world geographical groups, according to Chaudhary (2001) and Zohary (1966, 1972).

List of the flora of Mecca

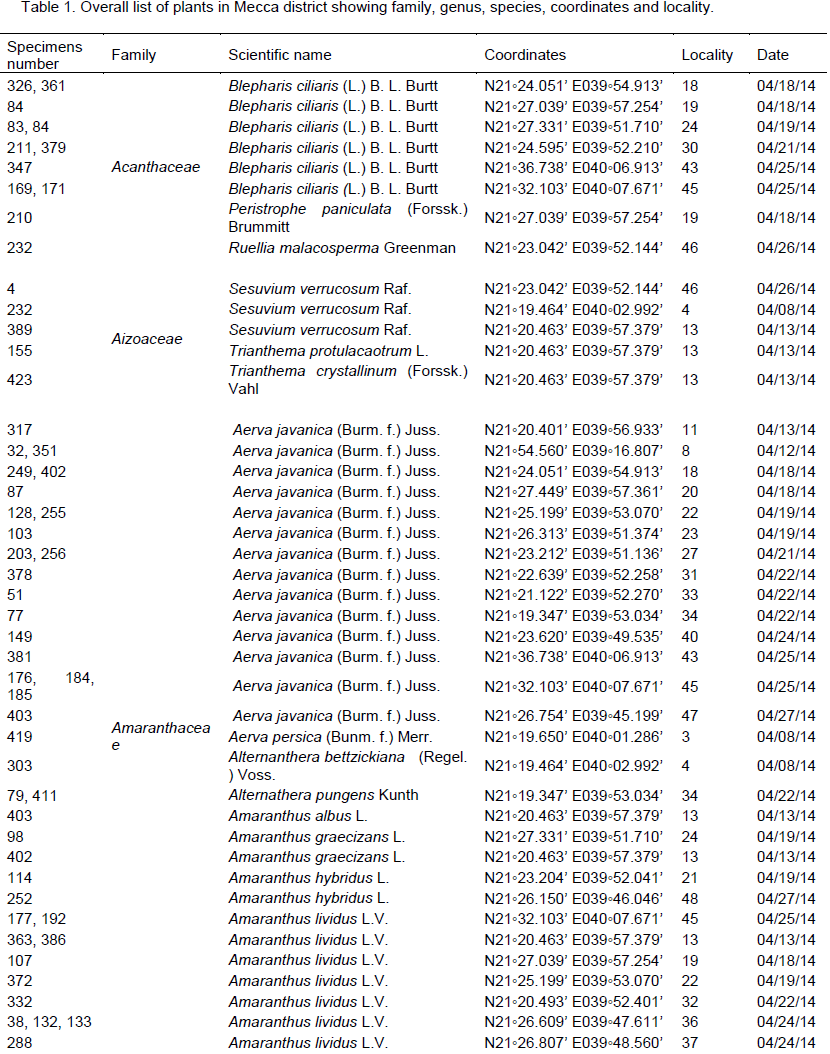

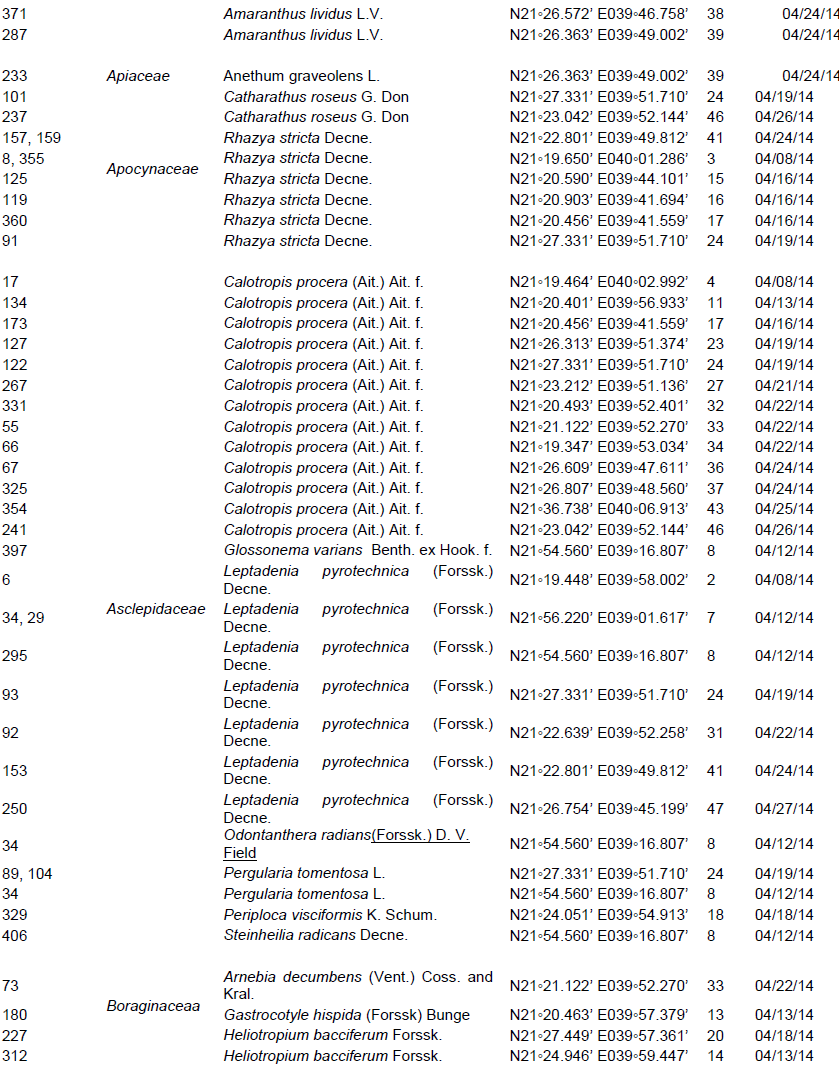

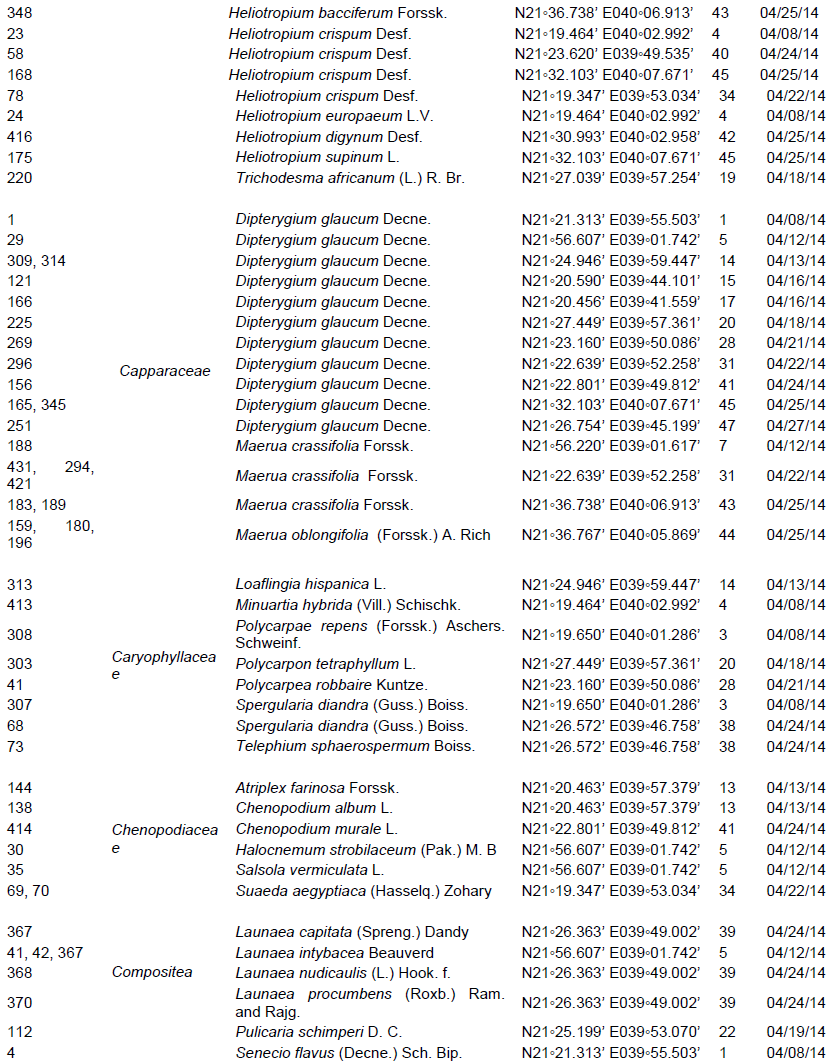

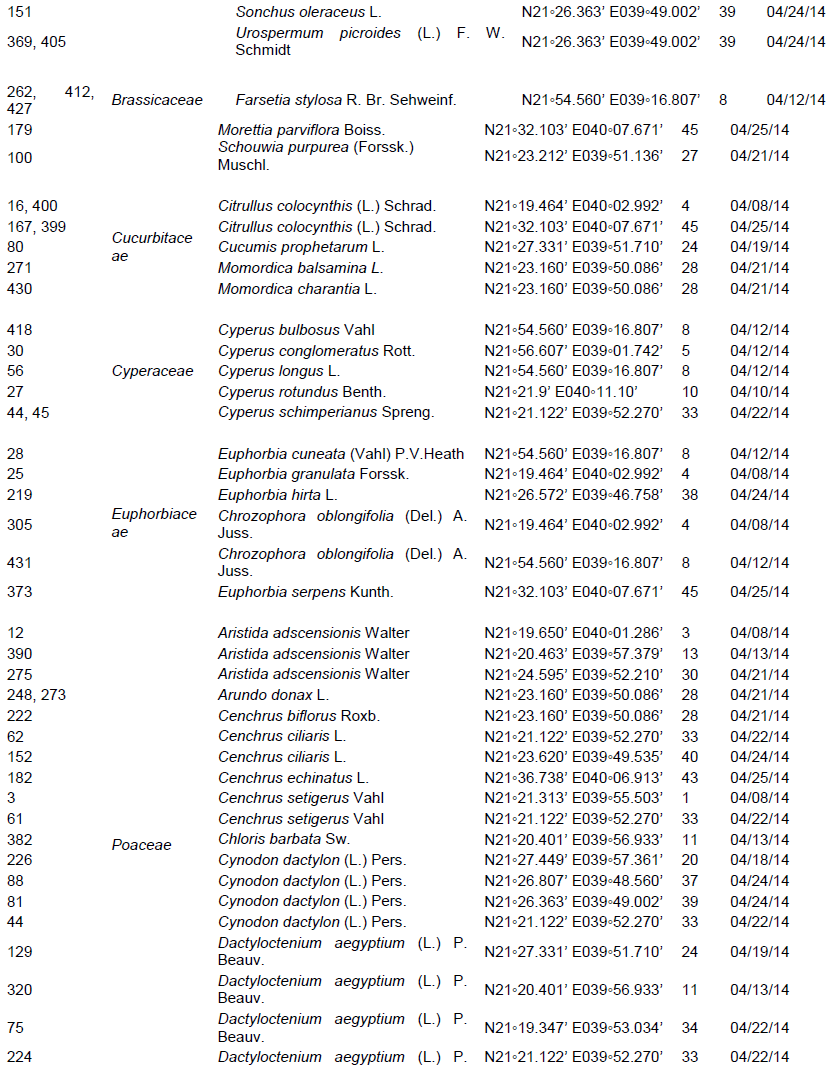

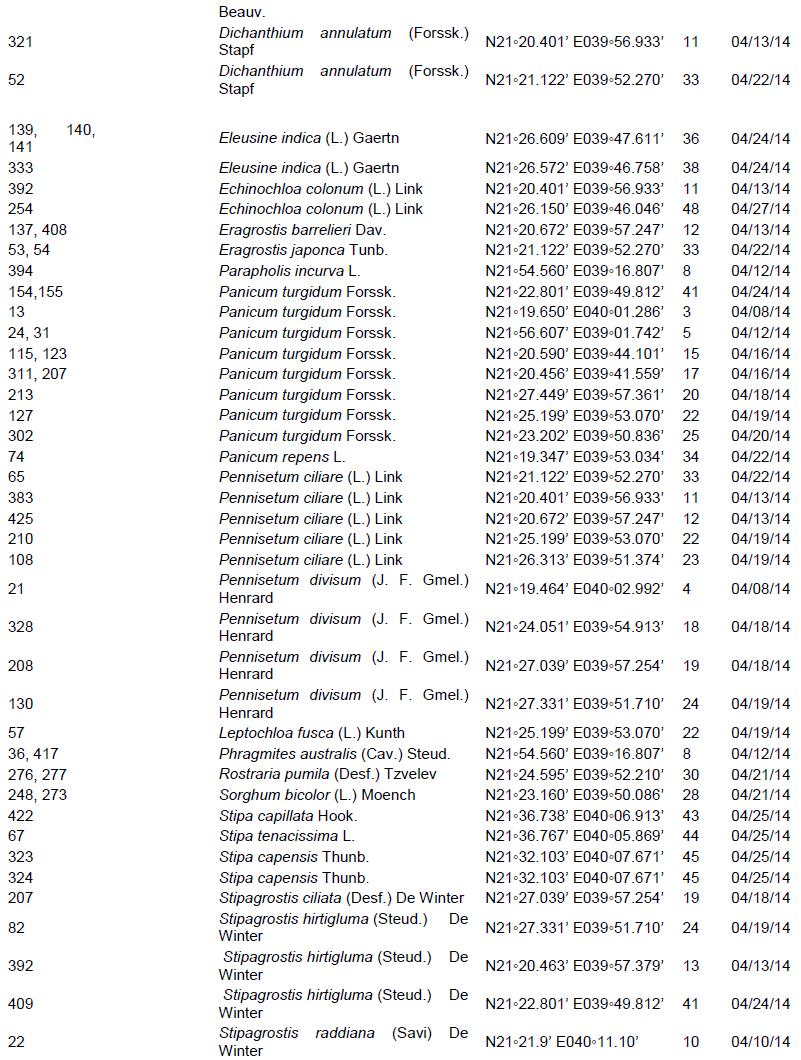

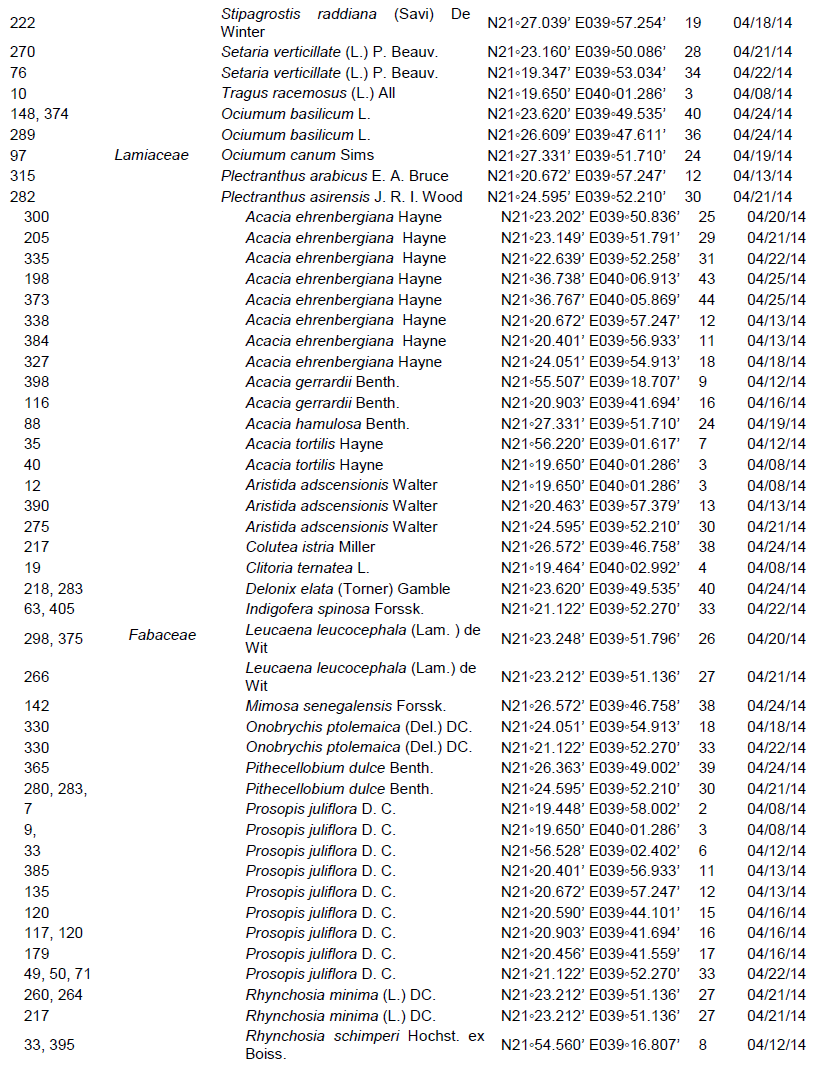

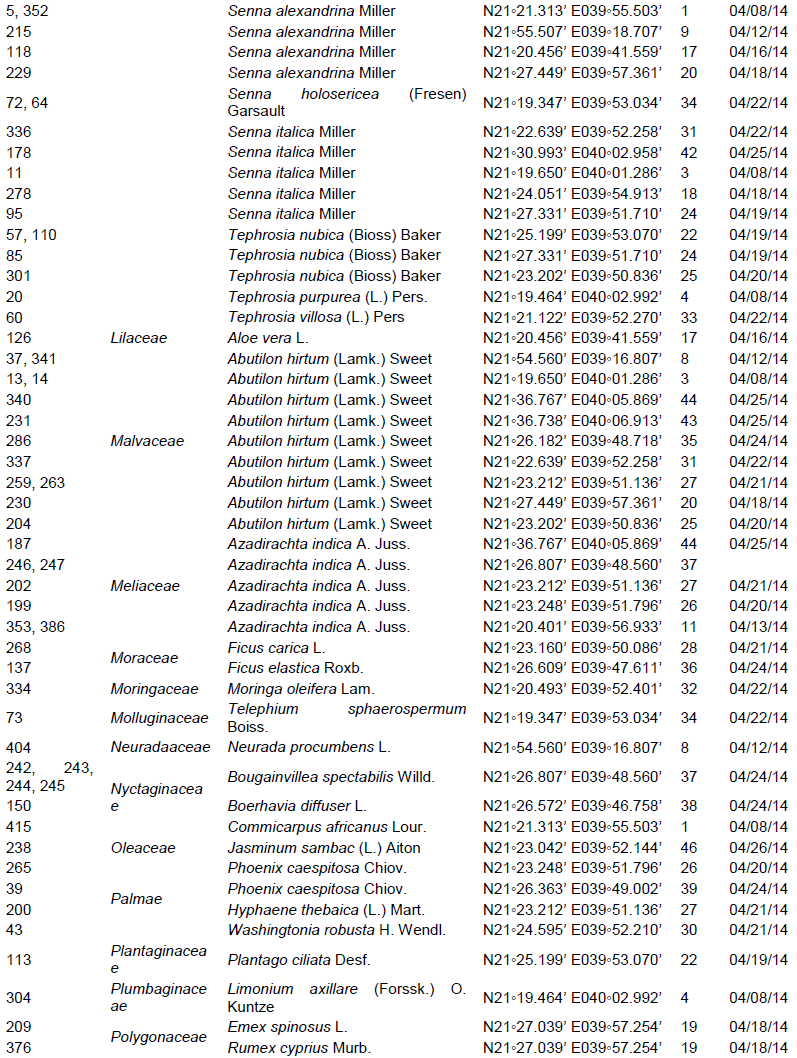

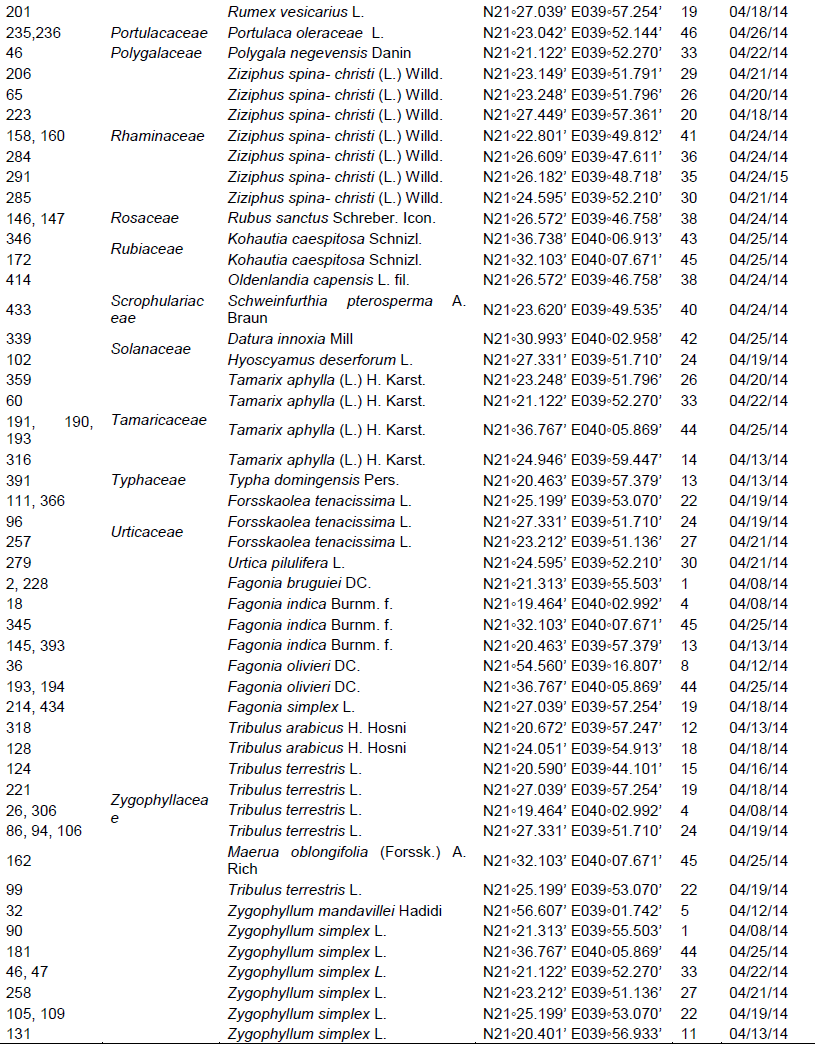

A number of 433 plant specimens was colleced. The total number of species is one hundred and eighty four (184) species belonging to one hundred and twenty five genera (125) and forty four (44) families (Table 1). It was found that these plants share characteristics with flora of Saharo-Arabian and Irano–Turranean (Al-Turki and Al-Olayan, 2003).

Moreover, forty eight (48) locations were found to have little diversity in general terms of biodiversity assessments due to the reason that there is limited change among these locations in terms of light intensity, relative humidity and topography.

Rare and unrecorded species

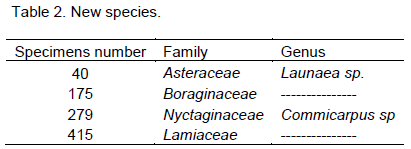

More significantly, the research has ended up with four new species considered as unknown and most probably new species to sciences. We could not confirm their identity at the time, waiting for new plant collection which has more details of the plant characteristic, specially, mature fruit. These specimens have the specimen numbers 40, 175, 279 and 415 (Table 2). There are nine species recorded as rare species to the flora of Saudi Arabia (Table 3).

Number and percentage of families and species in flora of Mecca

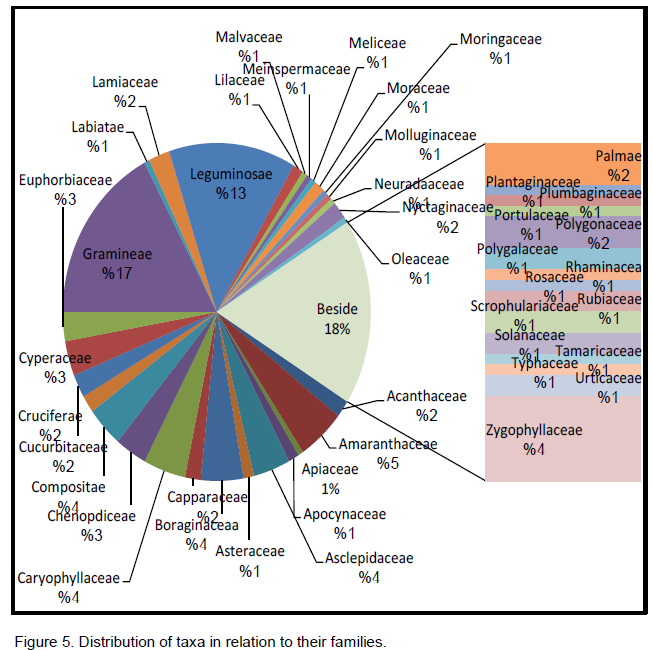

It was found that there are forty four (44) families in the flora of Mecca and the most prevalent one is Poaceae with 16.94% followed by Fabaceae with a percentage of 13.11% and Amaranthaceae with 4.92% while the lowest plant families are Apiaceae, Malvaceae Menispermaceae, Meliaceae, Moringaceae, Molluginaceae, Neuradaceae, Oleaceae, Plantaginaceae, Plumbaginaceae, Portulacaceae, Rhaminaceae, Rosaceae and Tamaricaceae with a percentage of 0.56% (Figure 5).

In relation to all species collected from Mecca, the most prevalent species are Calotropis procera with percentage 4.21% followed by Aerva javanica with percentage 3.93%, Dipterygium glaucum and Panicum turgidum both with percentage 3.37% and Abutilon hirtum with percentage 2.81% while the lowest recorded percentage is 0.28% in the following species Peristrophe paniculata, Ruellia malacosperma, Trianthema protulacaotrum, Trianthema crystallinum, Aerva persica, Alternanthera bettzickiana, Alternanthera pungens, Amaranthus graecizans, Amaranthus hybridus, Pulicaria schimperi, Steinheilia radicans, Periploca visciformis, Odontanthera radians etc.

Chorotype of taxa

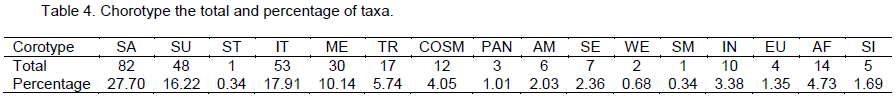

The analysis of flora is necessary to display the chorotypes of the species, Saharo-Arabian (SA); Sudano-Zambezian (SU); Sudanian territories (ST); Irano-Turanian (IT); Mediterranean (ME); Tropical (TR); Cosmopolitan (COSM); Panotropic (PAN); American (AM); Euro-Siberian (ES);, W Europe (WE); Africa (AF); and Asia (SI).

The largest number of chorotype groups is the Saharo-Arabian with a percentage of 27.70%, then Irano-Turanian with a percentage of 17.91% and followed by Sudano-Zambezian with a percentage of 16.22%, while the least number are Sudanian territories, Sahalian Somali and Madagascar with a percentage of 0.34% This percentage of plant chorotype groups agrees with the results found in this study since no records for American and W Europe or Euro-Siberian, since the study area does not fall within these terretories.

Life-form of all species and uses of plants

In the current study, the Life-forms of all species in Mecca district follow Raunkiaer scale as shown in Figure 8, whereas each species will be presented by its initial such as: H, hemicryptophyte; Ch, chamaephytes; GH, geophytes-helophytes; Ph, phanerophytes; Th, therophytes and He, helophyte. In relation to all species collected from Mecca, the most prevalent life-forms are therophytes with 41% followed by chamaephytes with 34% followed by phanerophytes with 11% (Figure 7).

In short conclusion the flora species and components in general are very important science; it deals with differenttypes of plants (medicinal, aromatic, poisonous... etc). This classification is very important and practical regarding human social structure and behavior and it is usually given the term of ethnobotanical uses of local communities which really affect their life style and the sustainable use of their resources (Oran, 2014; Oran and Al-Eisawi, 2014).

Overall, during the identification of the collected samples of plants in relation to their usages, they can be classified

into medicinal plants representing 71 species, species economical plants, 46 species; aromatic plants, 5 species; poisonous plants, 18 species; range grasses (fodder grasses) plants, 69 species; ornamental plants, almost 47 species; wood (fuel) plants, 29 species; other uses, about 4 species (Table 5, Figure 8). The most popular medical plant in Mecca is Senna italica Miller, which is used as laxative. Senna is a very well-known universal plant laxative used in medical industry as well as herbal medicine known in Arabic Language as Sanamekka; as clearly shown, the scientific name of the plant seems as originally taken from its old, local Arabic name. The plant at present is commonly used in the study area, Saudi Arabia, the Arabian Peninsula, Majority of the Arab World and India (Michael et al., 1999).

Saudi Arabia as mentioned earlier is a huge country with variable biogeographic regions. Therefore, it is very rich in biodiversity and special groups at the generic level such as Alloe, Caralluma, Acacia, or at the family level, such as Resedaceae, Leguminosae (Fabaceae) and Amaranthaceae.

The number of the recorded species in general in Saudi Arabia is increasing day after day based on new field trips and biodiversity surveys. As an indicator of that; is the first number 1500 species which was recorded by Migahid between the years 1974-1988. Later on the number was raised to reach 2300 within a period of about 30 years; this is based on the records given in the Flora of Saudi Arabia (Chaudhary, 1999-2001; Alfarhan et al., 2005; Masrahi et al., 2012). This is very true for the Flora of Egypt which was recorded to be less than 1700 species by Täckholm (1974) and raised to over than 2000 species by Bolous (1999-2005) in the new flora of Egypt. The same thing applies to Jordan, in the First Checklist of Vascular Plants of Jordan 2087 species (Al-Eisawi, 1982); recently a new checklist for the flora of Jordan was produced including 2545 species (Al-Eisawi, 2013). All of these examples indicate that the flora and biodiversity in the Arab world is not really extensively studied, in fact it is still very much under studied and needs further surveys in a wide field of biodiversity knowledge especially, insects and invertebrate biology.

However, this study is restricted to specific part of Saudi Arabia which is Holy Mecca. Accordingly, Mecca district is located in the west of Saudi Arabia in an arid zone of Saudi Arabia. Mecca is a restricted area for foreign visitors, therefore, it has been very little times investigated and thoroughly studied. Accordingly, it was selected for investigation using a local resident person who knows the various parts and has access and local help to survey the study are.

Based on this study where 184 species were collected and identified from this restricted area, it shows that it contains 8.48% of species from the total flora of Saudi Arabia. In this study, 80 more species have been recorded as additional species to the Flora of Mecca since the publication of the paper by Abdel Khalik et al. (2013). They recorded only 104 species. It is more likely that intensive collection at the year around would possibly discover more species. Mecca is considered to be poorly investigated since it is a restricted area to nonmuslim visitors. The most prevalent species recorded in this study are Calotropis procera, Aerva javacica which typical species of dry subtropical ecosystem, similar to conditions prevailing in Jordan Rift Valley, Southern Egypt, and Sudan and extending to the Indian peninsula (Al-Eisawi, 1996).

In terms of floristic and vegetation composition in the studied area

Poaceae and

Fabaceae are represented by the highest number of species (31 and 24, respectively). The dominance of members of

Poaceae and

Fabaceae coincides with the findings reported by Al-Turki and Al-Olayan (2003), El-Ghanem et al. (2010) and Abdel Khalik

et al. (2013).

The results show that the most chorotype distribution in the study area is Saharo-Arabian (27.70%), followed by Irano-Turanian (17.91%) and then Sudano-Zambezian (16.22%). A floristic analysis shows that the majority life-form of plants in the study area is therophytes followed by chamaephytes, phanerophytes as a result of adaption to the hot dry climate.

The study shows also that the most highly percentage for uses of plants was used as medicinal plants with a percentage of 24.57% followed by grazing plants with percentage of 23.88% while the least percentage was a aromatic plants with a percentage of 1.73%. It is worth mentioning here that the aim of this study was only survey of biodiversity, then classifying plant uses without working on their chemical constituents, but based on their records in previous literature (Al-Eisawi, 2014, 2015; Oran and Al-Eisawi, 2014, Oran, 2014).

The plants in Mecca region are predominately arid zone plants, where the leaves are covered with a waxy layer and have large roots and branched which came as a result of the increase in the rate of photosynthesis and search for water (Michael et al. 1999).

During this research, differences in the thickness of leaves and waxy layer of plant Calotropis procera was observed; the thickness of leaves and waxy layer is related to the water availability. When water is available the thickness of leaves and waxy layer will decrease and vice versa.

In conclusion, it is expected that further studies on the biodiversity of organisms will take place, in addition to vegetation and ecophysiology parameters. The vegetation in general and dry ecosystem in particular, extremely varies from year to year based on environmental conditions especially, rainfall and prevailing temperature.

The author(s) have not declared any conflict of interests.

The authors would like to thank the University of Jordan for the facilities and support especially, during sabbatical year. Also thanks are due to the Missouri Botanical Garden and to the University of Washington, St. Louis for their kind invitation and the use of their facilities.

REFERENCES

|

Abdel KK, El-Shikh M, El-Aidarous A (2013). Floristic diversity and vegetation analysis of wadi Al-Noman, Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Turkish J. Bot., 37:894-907.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Al-Amri M Co. (2007). Doing Business in Saudi Arabia. BDO International, 1:1-26. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia.

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Eisawi DMH (1982). List of Jordan Vascular Plants. Mitt. Bot. München, 18:79-182.

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Eisawi DMH (2013). Flora of Jordan Checklist-Revised Edition. The University of Jordan Press, Jordan.

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Eisawi DMH (1996). Vegetation of Jordan. UNESCO- Regional Office for Science and Technology for the Arab States. Cairo, Pp.266.

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Eisawi DMH (2014). Vegetation community analysis in Mujib Biosphere Reserve, Jordan J. Nat. History. 1:35-58.

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Eisawi DMH (2015). Medicinal plants in Mujib Biosphere Reserve, Jordan. Int. J. Pharm. Therapeut. 6(1):25-32.

|

|

|

|

|

Alfarhan A (2011). A floristic account on Raudhat Khraim Central province, Saudi Arabia. Saudi. J. Bio. Sci., 8:80- 87.

|

|

|

|

|

Alfarhan A, Al-Turki T, Basahy A (2005). Flora of Jizan Region. King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 1: 1-523.

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Khamis HH, Al-Hemaid F, Ibrahim A (2012). Diversity of Perennial Plants at Ibex Reseve in Saudi Arabia. J. Animal Plant Sci., King Saud University Saudi Arabia, 22 (2) 484-492.

|

|

|

|

|

Almazroui M, Islam, M, Athar H, Jonesa P, Rahmana, M (2012). Recent climate change in the Arabian Peninsula: annual rainfall and temperature analysis of Saudi Arabia for 1978-2009. Int. J. Climatol., 32: 953–966.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Said M (1993). Traditional Medicinal Plants of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh. Amer. J. Chinese Med., 21:291-298.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Alshareef A (1984). Geography of Saudi Arabia South-West of the Kingdom. Dar Almerikh, Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 2: 1- 488.

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Turki T, Al-Olayan H (2003). Contribution to the Flora of Saudi Arabia: Hail Region. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 10: 190-221.

|

|

|

|

|

Ashrae H (2005). Design condition for Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Fundamentals (SI), 1:1-2.

|

|

|

|

|

Bolous L (1999-2005). Flora of Egypt, Al-Hadara Publishing. Cairo, Egypt. 1-4.

|

|

|

|

|

Chaudhary S (1989). Grasses of Saudi Arabia. Regional Agriculture and water research center Ministry of agriculture and water kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 1: 1-465.

|

|

|

|

|

Chaudhary S (1999). Flora the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Illustrated. National herbarium ministry of agriculture and water Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 1: 1-691.

|

|

|

|

|

Chaudhary S (2000). Flora the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Illustrated. National herbarium ministry of agriculture and water Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 2(3):1-432.

|

|

|

|

|

Chaudhary S (2001). Flora the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Illustrated. National herbarium ministry of agriculture and water Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 2(1):1-675.

|

|

|

|

|

Chaudhary S (2001). Flora the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Illustrated. National herbarium ministry of agriculture and water Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 2(2):1-542.

|

|

|

|

|

Chaudhary S, Akram M (1987). Weeds of Saudi Arabia and the Arabian Peninsula. Regional Agriculture and water research center Ministry of agriculture and water kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 1:1-246.

|

|

|

|

|

Chaudhary S, Al-Jowaid A (1999) Vegetation of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. National agriculture and water research center ministry of agriculture and water kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 1: 1-689.

|

|

|

|

|

Chaudhary S, Al-Jowaid A (2013) Vegetation of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. National agriculture and water research center ministry of agriculture and water kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 1: 1-680.

|

|

|

|

|

Chaudhary S, Zawawi M (1983). A Manual of Weeds of Central and Eastern Saudi Arabia. Ministry of agriculture and water Regional Agriculture and water research center kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 1: 1-326.

|

|

|

|

|

Daur I (2012). Plant Flora in the Rangeland of Western Saudi Arabia. Pak. J. Bot., 44: 23-26.

|

|

|

|

|

El-Ghanim W, Hassan L, Galal T, Badr A (2010). Floristic composition and vegetation analysis in Hail region north of central Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci., 17: 119–128.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

El-Ghazali G, Al-Soqeer A (2013). Achecklist of the weed flora of Qassim region, Saudi Arabia. Australian J. Basic Appl. Sci., (2): 900-905.

|

|

|

|

|

El-Ghazali G, Al-Khalifa K, Saleem G, Abdullah E (2010). Traditional medicinal plants indigenous to Al-Rass province, Saudi Arabia. J. Med. Plants Res., 4(24):2680-2683.

|

|

|

|

|

Feinburn-Dothan N (1978). Flora Palaestina, Part III. Jerusalem. Isr. Acad. Sci. Humanities. Jerusalem.

|

|

|

|

|

Feinburn-Dothan N (1986). Flora Palaestina, Part IV. Jerusalem. Isr. Acad. Sci. Humanities. Jerusalem.

|

|

|

|

|

Masrahi Y, AL-Huqail A, AL-Turki T, Thomas J (2012). Odyssea mucronata, Sesbania sericea, and Sesamum alatum–new discoveries for the flora of Saudi Arabia. Turk. J. Bot., 36:39-48.

|

|

|

|

|

Meelad M (2006). Flora Study Series in Saudi Arabia: A Study of the Soil of Makkah- Madinah Road until Rabigh. Umm Al-Qura. Univ. J. Sci. Med. Eng. 18:13 -29.

|

|

|

|

|

Michael FT, Omar RL, Thomas AK (1999). Responses of Tropical Understory Plants to a Severe Drought: Tolerance and Avoidance of Water Stress1. Biotropica, 31(4):570-578.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Migahid A (1978). Flora of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh University. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 1:1-647.

|

|

|

|

|

Migahid A (1988). Flora of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh University. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 3: 1-647.

|

|

|

|

|

Migahid A, Hammouda M (1974). Flora of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh University. Riyadh. Saudi Arabia, 1:1-574.

|

|

|

|

|

Migahid A, Shalaby A, Ali M, Abu-zinda A, Hajara H, Batanouny K (1977). Proceedings of the first conference on the biological aspects of Saudi Arabia held at the Riyadh University. Riyadh University press. Riyadh Saudi Arabia, 2:1-368.

|

|

|

|

|

Oran SA (2014). The Status of Medicinal Plants in Jordan. J. Agric. Sci. Technol., A and J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B, 4(6A):461-467).

|

|

|

|

|

Oran SA, Al-Eisawi DM (2014). Medicinal Plants in the High Mountains of Northern Jordan. Int. J. Biodiv. Conserv., 6(6):28-40.

|

|

|

|

|

Rahman M, Mossa J, Al-Said M, Al-Yahya M (2004). Medicinal plant diversity in the flora of Saudi Arabia 1: A report on seven plant families. Fitotherapia, 75:149–161.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Raunkiaer C (1934). Life Forms of Plants and Statistical Plant Geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Sher H, Aldosari A (2013). Ethnobotanical survey on plants of veterinary importance around Al-Riyadh (Saudi Arabia). Afri. J. Pharm. Pharmacol., 7(21): 1404-1410.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Täckholm V (1974). Student's Flora of Egypt. Second Edition. Published by Cairo University. Printed by Cooperative Printing Company. Beirut. Lebanon. Pp. 888.

|

|

|

|

|

Zohary M (1957). A contribution to the flora of Saudi Arabia. J. Linnaean Society of London, Bot., 55:632-643.

|

|

|

|

|

Zohary M (1966). Flora Palaestina. Part 1. Israel Acad. Sci. and Humanities, Jerusalem.

|

|