ABSTRACT

This paper explores the effect of corporate governance on voluntary disclosure. The investigation of the research question was based on hand-collected data from annual reports for a sample of 93 non-financial listed firms on the Athens Stock Exchange for 2017. Using several items to create a voluntary disclosure index, the authors investigate the arguments that ownership structure, board of directors (board) and audit committee affect voluntary disclosure. The results indicate that some corporate governance characteristics (block ownership and board independence) reduce voluntary disclosure, while others (board and audit committee size) increase the extent of disclosure. Additionally, a positive effect on the voluntary disclosure concluded for the size of the firm and the size of the audit firm. The results have implications for capital market regulators and listed firms wishing to reduce conflicts between the firm and its related parties and to strengthen the confidence to the firm’s governance by using corporate governance structures. This paper contributes to the academic debate on the relationship between corporate governance and voluntary disclosure by assessing the effect of ownership structure, board of directors (board) and audit committee on the extent of voluntary disclosure.

Key words: Corporate governance, disclosure, voluntary disclosure, ownership, board of directors, audit committee.

The purpose of this paper is to extend prior research in the field of voluntary disclosure by exploring the association of corporate governance with the extent of voluntary disclosure in Greece. Many studies in different institutional contexts show that several elements of corporate governance are likely to have a positive or negative effect on firm’s disclosure processes (Fiori et al., 2016; Sarham and Ntim, 2019; Zhou, 2019; Saha and Kabra, 2021). The Greek context constitutes an interesting case for investigating voluntary disclosure and corporate governance.

The Greek crisis in 2009 resulted in a significant drop in the value of the shares of listed firms. One of the main reasons was the decline in investors’ confidence, as the crisis was not only a stock market crisis but mainly fiscal and economic crisis. Corporate governance plays an important role in restoring confidence between stakeholders. A crucial procedure in this direction is to increase the flow of information to reduce information asymmetry with financial statements being a key information process in the communication with stakeholders. Although annual reports are the first source of information for investors and other related parties, they have significant limitations as other sources of information beyond financial performance are also used to evaluate a company that is not adequately presented in the annual report (Fiori et al., 2016). Moreover, the current business environment challenges the adequacy of the limited mandatory information and as the nature and extent of information differs from the past, the need for companies to voluntarily disclose more information arises (Elfeky, 2017). Additional voluntary disclosures in the annual reports can therefore reduce the information gap, enhance accountability and improve decision making.

Previous studies have examined disclosure issues in the Greek context (Leventis and Weetman, 2004a, 2004b; Galani et al., 2011; Iatridis and Alexakis, 2012; Skouloudis et al., 2014; Tasios and Bekiaris, 2014), without focusing on the impact of corporate governance on voluntary disclosure. This study investigates the effect of specific corporate governance elements on the extent of voluntary disclosure that has not been adequately examined in Greece and contributes to better understanding on the determinants of voluntary disclosure In addition, the results of this study complement the existing literature on the discussion of corporate governance and its effect on firms’ disclosure. Arguments were produced about the association of corporate governance elements and voluntary disclosure in an environment with specific characteristics such as the Greek stock market, where quite often the CEO is also the chairman of the board (Vadasi et al., 2021), there is a single board (one-tier system) involving executive and non-executive directors, which may lead to information asymmetry (Paape, 2007), founding family often plays an important role (in the results of this study the mean proportion of ordinary shares owned by the founding family and their relatives reached 57%) which may lead a firm to face more agency problems.

Corporate governance characteristics that have been identified in the literature and are expected to affect disclosure relate to shareholder structure, board of directors (board), and audit committee. A voluntary disclosure index with 65 items, including strategic, non-financial and financial information, was designed to assess the extent of voluntary disclosure (Allegrini and Greco, 2013; Chau and Gray, 2010, 2002; Leventis and Weetman, 2004a; Meek et al., 1995). Using regression model to analyze data from the annual reports of 93 non-financial listed firms on the Athens Stock Exchange (ASE) in fiscal year 2017, the authors concluded to a significant effect of specific corporate governance elements on voluntary disclosure.

Specifically, we found a positive effect of board size and audit committee size on voluntary disclosure. According to board independence the results indicate a negative effect on voluntary disclosure, while negative effect was also found for ownership structure, specifically for the existence of block owners. Finally, evidence was found that the size of the firm and the size of the audit firm increases voluntary disclosure. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses Greek context, section 3 provides the literature review and hypotheses development, section 4 contains the voluntary disclosure index, the sample selection and the research model, section 5 presents the empirical results and section 6 reaches a conclusion.

Corporate governance and disclosure in Greece

The Greek stock market is an interesting case to study due to the significant financial crisis that occurred during 2009-2018 (Galani et al., 2011). The Greek stock exchange (ASE) experienced a significant growth during 1990-1999 as the improvement of the economy brought the macroeconomic fundamentals of Greece closer to the European average (Patra and Poshakwale, 2006). The peak of the market in 1999 gave way to a sharp correction in 2000. The following decade is described as a period of consolidation of the Greek stock market. This course was violently interrupted by the Greek sovereign debt crisis (2009-2018) which was characterized by violent upheavals and structural changes in the Greek economy and therefore in the Greek stock market. However, Greece had to face additional problems such as high budget deficit (with ever-increasing revisions), high public debt, low competitiveness, bank liquidity, red loans, and low private investment, among others (Nerantzidis and Filos, 2014; Kourdoumpalou, 2016; Bekiaris, 2021). In times of constant and violent change where trust is undermined, financial disclosure reporting, mandatory and voluntary, is the main bridge of establishing confidence between firms and investors (Boman and Elvin, 2018). A key element in confidence-building is good corporate governance which aims to defend the interests of all the participating parties. Corporate governance requires increased accountability through voluntary disclosure, as it reduces information asymmetries and improves relations between firms and stakeholders.

The evolution of corporate governance in Greece follows a series of steps related to various national (e.g., rise and fall of the stock market in 2000, Greek financial crisis in 2010, Folli Follie scandal) and international events (e.g., scandal in Enron, international financial crisis of 2008). More specifically in 1999 the Committee on Corporate Governance in Greece issued a white paper titled “The principles of corporate governance in Greece: recommendations for its competitive transformation”. Since then, the main characteristic of Corporate Governance in Greece is the existence of a multitude of laws, acts, regulatory decisions and legal provisions (e.g. L. 2190/1920, HCMC 5/204/2000, L. 3016/2002, L. 3693/2008, L. 3873/2010) which are following national and global trends and events (e.g., L. 3016/2002 follows Sarbanes-Oxley Act and L. 3873/2010 introduces “comply or explain rule” just after the outbreak of Greek crisis). Nevertheless, corporate governance requirements in Greece are reviewed regularly since 1999. For instance, the new Corporate Governance Law 4706/2020 was enacted in late 2020 (after the Folli Follie scandal) by the Hellenic Capital Market Commission (HCMC) empowering corporate governance legislation.

Disclosure rules governing the content of the annual reports for listed companies are defined by law 3556/2007, as well as the decisions of the board of directors (board) and the circulars of the Hellenic Capital Market Commission (HCMC). One of the most significant attempts to improve the quality of the financial reporting in Greece occurred in 2005, with the mandatory application of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) for all firms listed on the ASE. Another significant change took place in 2014 with law 4308 which introduced Greek Accounting Standards in an E.U. effort to align accounting principles across its members.

Previous studies have investigated disclosure issues in Greece; In a study conducted by Leventis and Weetman (2004a) on the annual reports of 87 listed firms on the ASE in 1997 the extent of voluntary disclosure was found to be relatively low. Iatridis and Rouvolis (2010) in their study found that firm size and debt and equity financing needs are determinants of the provision of voluntary IFRS disclosures before the official period of adoption (2005). Furthermore, Iatridis and Alexakis (2012) in their investigation of 171 Greek firms for 2006 -2009 period found that voluntary disclosers exhibit higher profitability and that the provision of voluntary accounting disclosures is negatively associated with earnings management. Finally, Tasios and Bekiaris (2014) studied annual reports of 72 listed firms on the ASE in 2011 found an adequate degree of average compliance with mandatory disclosure requirements, while Skouloudis et al. (2014) studied non-financial reports of firms operating in Greece in 2005 argued that there is much room for improvement as significant gaps were found in the firms’ disclosure practices. This paper examines the association between corporate governance characteristics and the extent of voluntary disclosure in 2017, a year of de-escalation of the crisis in Greece.

“The principles of corporate governance in Greece: recommendations for its competitive transformation”, available at: https://ecgi.global/code/principles-corporate-governance-greece-recommendations-its-competitive-transformation.

Disclosure, mandatory and voluntary, is a crucial element of corporate reporting (Doni et al., 2019; Krasodomska et al., 2020). Voluntary disclosure concerns the provision of information by firm’s management in addition to the disclosure requirements arising from accounting principles and rules of regulatory authorities. This information helps rational financial decisions to be made by third interested parties who make use of the annual reports of listed firms. Therefore, voluntary disclosure can be considered as a control mechanism like corporate governance (Allegrini and Greco, 2013) and can be examined through the framework provided by agency theory (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). According to agency theory, there is a possibility that managers will act against shareholders’ interests, so an attempt is made to align the interests of the two groups. However, full alignment is difficult, so various management monitoring mechanisms are used (Cohen et al., 2002). Voluntary disclosure can mitigate agency costs as managers, by disclosing additional information, point to third parties concerned that they are acting in line with shareholders’ interests (Barako et al., 2006). The extent of voluntary disclosure is affected by the corporate governance and ownership structure as indicated in the literature.

Enache and Hussainey (2020) investigated the joint effect of voluntary disclosure and corporate governance on firm performance, arguing that the two mechanisms may be independent, substitutive, or complementary. Their findings on data from a sample of US biotech firms indicate a substitutive effect on firm performance, for firms with products in advanced stages of development. Zhou (2019) by using a sample of Chinese publicly traded manufacturing firms found that corporate aspects like board of directors and ownership structure are associated with the decision of voluntary disclosure on corporate social responsibility reports. Two meta-analysis studies investigated the effect of corporate governance on disclosure; Samaha et al. (2015) analyzed 64 empirical studies concluding that corporate governance affects voluntary disclosure, but geographical location mitigates such as this relationship for some corporate governance variables, such as board size and composition. Lagasio and Cucari (2019) in a meta-analysis of 24 empirical studies investigated the relationship between several corporate governance elements and environmental, social and governance disclosure, concluding in several significant associations (e.g., board independence, board size, female members).

Many studies have investigated the effect of corporate governance variables on voluntary disclosure in different institutional settings (Barako et al., 2006; Patelli and Prencipe, 2007; Akhtaruddin and Haron, 2010; Chau and Gray, 2010; Gisbert and Navallas, 2013). By constructing an index of voluntary disclosure with data from the annual reports of listed firms in various countries, they found a significant effect of various corporate governance elements on voluntary disclosure. Relying on prior literature, we identified three basic corporate governance areas that are expected to be associated with voluntary disclosure; namely, ownership structure, board of directors, and audit committee.

Hypothesis development

Literature review of theory and prior research indicates that several governance and companies’ characteristics have been used as explanatory variables of the relationship between voluntary disclosure and corporate governance. The variables of this study were selected based on the following criteria: a) corporate governance theory and results of prior research, c) relevance and importance of the variables for the objectives of the study and c) the characteristics of the environment where the study was conducted. Based on the above the following corporate governance characteristics were examined:

1.

2.

3.

Ownership structure

Previous studies examined the link between various ownership structure variables and voluntary disclosure (Eng and Mak, 2003; Patelli and Prencipe, 2007; Gisbert and Navallas, 2013; Elfeky, 2017). Akhtaruddin and Haron (2010) found that the proportion of executive share ownership to the total shares of the firm is negatively related to voluntary disclosure. The same result was reached by Eng and Mak (2003), while they did not find evidence for a significant effect of blockholder ownership (percentage of equity ownership by substantial shareholders – with equity of 5% or more). Elfeky (2017) and Kolsi (2017), on the other hand, found a negative effect of blockholder ownership on voluntary disclosure, suggesting that capital concentrated firms disclose less information than other firms. Additionally, Lagasio and Cucari (2019) reported a negative effect of board ownership on environmental social governance disclosure. From the other side, evidence has been found that dispersal of equity can lead to better disclosure conditions; Chau and Gray (2002) found a positive association between wider ownership and voluntary disclosure and Patelli and Prencipe (2007) reported a positive impact of the percentage of share capital owned by shareholders who possess less than 2% of the share capital on the extent of voluntary disclosure. In line with that, Barako et al. (2006) found that lower disclosure appears for firms with higher proportion of shares held by the top 20 shareholders. Based on these arguments we expected a negative impact of blockholder ownership on voluntary disclosure.

Another element of ownership structure that has been extensively examined on the literature is family ownership, an important parameter as firms with high percentage of family ownership face significant agency problems. Previous studies indicated a negative relationship between the percentage of shares held by family members and voluntary disclosure (Chau and Gray, 2010, 2002). In the same direction, other studies (Ho and Wong, 2001; Haddad et al., 2015) reported that firms with more family board members disclose less information. Ali et al. (2007) found that family firms that report better quality earnings, disclose less information about their corporate governance practices, although they are more likely to warn for bad news. Chen et al. (2008) also found that family firms provide more earnings warnings, but less earnings forecasts and conference calls. Drawing on these arguments, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H1. The extent of voluntary disclosure is negatively associated with blockholder ownership.

H2. The extent of voluntary disclosure is negatively associated with the level of family shareholding.

Board of Directors (board)

The board is an important mechanism of corporate governance. Many studies have investigated board structure effect at various measures, such as firm performance and earnings management; Gaur et al. (2015) found that board size and CEO duality positively affect firm performance, while board independence has a negative effect on firm performance. Shahrier et al. (2020) concluded that the independent members of the board are positively associated with firm performance, while CEO duality adversely affects firm performance. In addition, González and García-Meca (2014) reported a positive relationship between board size and earnings management and a negative one between board independence and earnings management. In the field of disclosure prior literature investigates the impact of three board structure elements, namely board size, board independence and CEO duality. Previous studies have shown a significant positive association between the number of board directors and the extent of voluntary disclosure (Allegrini and Greco, 2013; Gisbert and Navallas, 2013; Samaha et al., 2015). Moreover, Lagasio and Cucari (2019) in a meta-analysis review found that board size enhances environmental social governance disclosure.

Another board structure element that was examined in the literature is the effect of board independence in voluntary disclosure, with the results indicating a positive (Chau and Gray, 2010; Gisbert and Navallas, 2013; Elfeky, 2017; Shan, 2019), negative (Eng and Mak, 2003; Gul and Leung, 2004; Barako et al., 2006) and no effect (Ho and Wong, 2001; Allegrini and Greco, 2013). Cases of positive effect suggest that the two control mechanisms co-exist (Patelli and Prencipe, 2007), while in cases of negative association it is suggested that independent directors substitute the monitoring role of disclosure (Eng and Mak, 2003). In addition, Lagasio and Cucari (2019) found that board independence enhances environmental social governance disclosure and Neifar and Jarboui (2018) found the same impact for operational risk voluntary disclosure.

The separation of the persons holding the positions of the CEO and the Chairman of the board seems to affect the extent of voluntary disclosure in different directions; Previous studies (Allegrini and Greco, 2013; Gisbert and Navallas, 2013; Alfraih and Almutawa, 2017) found that CEO duality is negatively associated with disclosure, while Chau and Gray (2010) discovered a positive relationship. In the cases of specific information disclosures, it was found that CEO duality negatively affects risk disclosure practices (Neifar and Jarboui, 2018; Alshirah et al., 2020) and does not improve environmental social and governance disclosure (Lagasio and Cucari, 2019). Different results are due to different theories; On the one hand, according to agency theory, CEO duality increases CEO’s power over the board, which is likely to reduce board’s ability to prevent speculative behavior on the part of management (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Stewardship theory, on the other hand, explains that a strong CEO who is also the chairman of the board can act as a steward of the firm resources and contribute to the implementation of effective control mechanisms (Donaldson and Davis, 1991). Based on the preceding discussion, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H3. The extent of voluntary disclosure is positively associated with board size.

H4. The extent of voluntary disclosure is positively/ negatively associated with board independence.

H5. The extent of voluntary disclosure is positively/ negatively associated with the CEO duality.

Audit committee

Audit committee as a standing committee of the board of directors in the context of the requirements of article 44, Law 4449/17, is a crucial mechanism of corporate governance. Audit committee assists the board in fulfilling its responsibilities towards shareholders and third parties, especially regarding financial reporting and monitoring procedures. In this context, previous studies have investigated the effect of the audit committee on the extent of voluntary disclosure (Gul and Leung, 2004; Samaha et al., 2015; Akhtaruddin and Haron, 2010). It was found that the presence of an audit committee in the firm is positively associated with firm’s voluntary disclosure (Ho and Wong, 2001; Barako et al., 2006). Moreover, Samaha et al. (2015) in a meta-analysis review of 22 studies found a positive relationship between audit committee and voluntary disclosure; the number audit committee members and the percentage of independent directors bears a positive effect on voluntary disclosure. In line with this argument, Akhtaruddin and Haron (2010) and Barros et al. (2013) argued that an increase in the number of independent directors in the audit committee increases voluntary disclosure. Drawing on these arguments, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H6. The extent of voluntary disclosure is positively associated with audit committee size.

H7. The extent of voluntary disclosure is positively associated with audit committee independence.

Voluntary disclosure index (VDI)

A disclosure index consisting of 65 items was constructed to measure the extent of voluntary disclosure. The index was based on prior research and specifically on Allegrini and Greco (2013), Chau and Gray (2010, 2002), Leventis and Weetman (2004a) and Meek et al. (1995) and categorized the elements of voluntary disclosure into three main categories: (1) strategic information (general corporate information, corporate strategy, research and development, projected information); (2) non-financial information (employee information, social policy and value-added information, directors’ information); (3) financial information (segmental information, ratios, financial review, capital market information).

The scoring procedure applied was dichotomous in which an item scored 1 if it was disclosed and 0 otherwise. In line with previous studies (Meek et al., 1995; Ho and Wong, 2001; Eng and Mak, 2003; Chau and Gray, 2010, 2002; Allegrini and Greco, 2013), the score given to the index items was not weighed to avoid the subjectivity of this process. Total disclosure score per firm was calculated as follows:

The detailed list of the 65 items included in the VDI is reported in the Appendix; Panel A provides information about categories and sub-categories of the VDI and Panel B provides the 65 items and their rates in the sample.

Sample selection

The sample comprises listed firms on the Athens Stock Exchange for the year ending 31.12.2017. Data were extracted from the annual reports which were released during 2018. Financial firms were excluded from the sample due to the specificity of their operations and their reporting requirements which differentiate them from other firms. Moreover, firms suspended from trading, firms with a reporting period other than 31.12.2017 and firms with missing data were also excluded from the final sample. The study is limited to one year (2017) as firms tend to follow a stable disclosure strategy over time (Botosan, 1997). Table 1 provides the sample selection process (Panel A) and industry distribution of the sample (Panel B).

Model specification

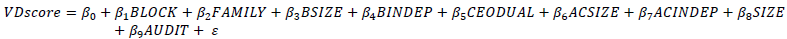

The following ordinary least square (OLS) regression model is examined in the study:

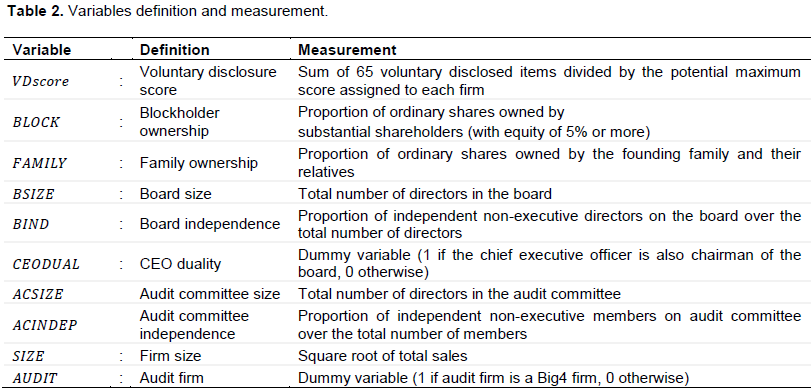

The model combines corporate governance variables (predictor variables) with firm characteristics (control variables). Predictor variables were used to test the arguments of this study as outlined in section 3; Control variables are based on the literature and involve factors that can potentially affect voluntary disclosure. Following previous studies, two control variables are included, namely firm size and audit firm. Large part of the literature reached the conclusion that firm size ( ) has a positive effect on voluntary disclosure (Akhtaruddin and Haron, 2010; Chau and Gray, 2010; Patelli and Prencipe, 2007; Allegrini and Greco, 2013; Scaltrito, 2016; Elfeky, 2017). In addition, many studies investigated the impact of the audit firm ( ) on voluntary disclosure, namely whether being the audit firm one of the large audit firms, plays a role in the degree of voluntary disclosure (Eng and Mak, 2003; Barako et al., 2006; Akhtaruddin and Haron, 2010). Chau and Gray (2010) found a negative relationship possibly indicating a substitute role of external audit regarding disclosure, while other researchers (Barros et al. 2013; Scaltrito, 2016; Elfeky, 2017) concluded on a positive impact of external audit quality on voluntary disclosure. The definition and measurement of the variables in the model is presented in Table 2. The statistical analysis of the data and the estimation of the regression model were performed with IBM SPSS (version 26).

Univariate analysis

Descriptive statistics for voluntary disclosure

Table 3 provides descriptive statistics for the total voluntary disclosure score and its subcategories for the 93 companies of our sample. Total average voluntary disclosure score (VDscore) was relatively low and amounted to 37.7%, with a minimum value of 16.9% and a maximum value of 78.5%. This indicates that listed companies on the ASE appear to be reluctant to disclose more information in their annual reports than that required by the regulatory framework. The same conclusion applies for the subcategories of the index. Average disclosure for strategic information amounted to 42.3% (SVDscore), for non-financial information to 36.3% (NFVDscore) and for financial information to 34.8% (FVDscore).

As seen in the appendix the items with the highest observed disclosure (above 95%), relate to information on products/services (100.00%), brief history of the firm (98.92%), profitability ratios (98.92%), cash flow ratios (97.85%) and assumptions underlying forecasts (97.85%).

On the other hand, the items with the lowest disclosure (below 5%), were qualitative analysis of competitors (4.30%), qualitative effect of inflation on assets (3.23%), market capitalization trend (3.23%), number of employees on research and development (2.15%), quantitative effects of inflation on results and assets (1.08%), and quantitative competitor analysis (0.00%).

From the above it can be concluded that listed firms on the ASE are more willing to disclose information that may attract customers and have a positive impact on the operations such as information regarding product/ services, the history of the firm or profitability. On the other hand, companies appear reluctant to disclose information that may harm their competitive advantage or have a negative impact, such as competitor analysis or the effect of inflation.

Descriptive statistics for independent variables

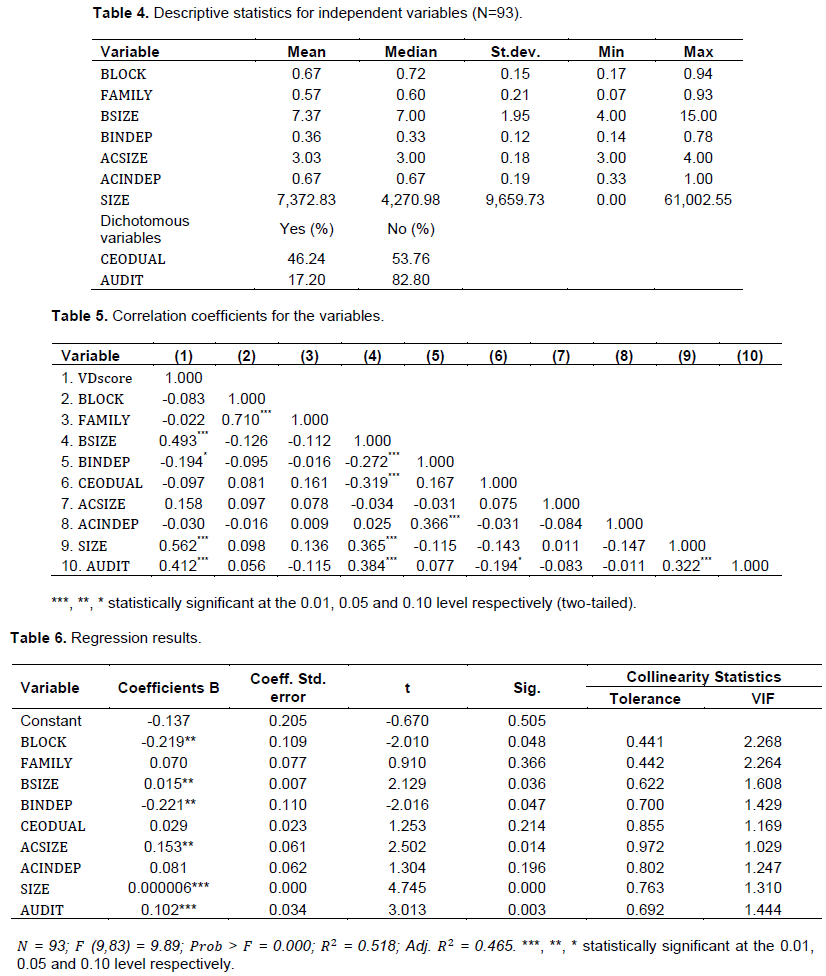

Table 4 reports the descriptive statistics for the independent variables (predictor and control) included in the regression model.

The ownership of the share capital was highly concentrated for the companies of the sample (BLOCK ) with a mean value of 67%. In addition, most of the firms were family owned with mean family ownership (FAMILY) amounting to 57%. Average board size (BSIZE ) comprised 7 members with a minimum of 4 members and a maximum of 15 members. Audit committees on average had 3 members (ACSIZE). About one third of the board members (36% - BINDEP) and two thirds of audit committee members were independent (67% - ACINDEP). CEO duality (CEODUAL) was observed on 46% of the firms of the sample, while the majority of the firms (83%) were audited by non big4 audit firms (AUDIT). The descriptive statistics indicate that the listed companies of the sample present high levels of ownership concentration and are in their majority family controlled. Although boards of directors appear to have an adequate number of independent members, a significant concentration in the decision-making power is observed.

Multiple analysis

Correlation analysis

Table 5 provides Pearson correlations for all variables in our model. Voluntary disclosure (VDscore ) is significantly positively associated with board size, firm size and audit firm size at the 1% level of significance, providing some evidence in support of these hypotheses. Furthermore, a significant negative association with board independence is observed at the 10% level of significance. As far as the independent variables are concerned, board size is significantly associated with board independence, with CEO duality, with firm size and with audit firm size. Moreover, board independence is significantly associated with audit committee independence; audit firm size is significantly associated with firm size and with CEO duality; and block ownership is significantly associated with family ownership. Although correlation results suggest that for several of the independent variables correlation coefficients are significant, correlation is not high (in excess of 0.80) to indicate multicollinearity (Gujarati, 2003; Field, 2018). In any case multicollinearity was also assessed with variance inflation factor (VIF), as in models with more than two explanatory variables correlations have limited power for the detection of multicollinearity (Gujarati, 2003).

Regression analysis

Table 6 presents the results of multiple regression model in which voluntary disclosure (VDscore) is used as the dependent variable and the set of predictor variables identified by the literature review. Results indicate a significant positive association between the extent of voluntary disclosure and the characteristics of board size, audit committee size, firm size and auditor type; there was a significant negative association with block ownership and board independence. The adjusted coefficient of determination R2 amounts to 46.52% and indicates that the research model has a satisfactory explanatory power, comparable or higher to other disclosure studies (Scaltrito, 2016; Elfeky, 2017; Kolsi, 2017). F value amounts to 9.89 and shows that the model is statistically significant (Prob > F = 0.0000). Breusch Pagan/Cook Weisberg test (chi2 = 3.56, prob > chi2 = 0.059) and White’s test ( chi2 = 44.49, prob > chi2 = 0.494) for heteroskedasticity indicate that the assumption of homoskedasticity is not violated. Τhe maximum value of VIF amounts to 2.27 and supports the lack of presence of multicollinearity in the research model. As a rule of thumb, a variable is considered highly collinear if the VIF exceeds 10 (Gujarati 2003).

The findings of the study provide support for the hypotheses H1 (BLOCK), H3 (BSIZE), H4 (BINDEP) and H6 (ACSIZE). Board size and audit committee size are positively associated with the level of voluntary disclosure (VDscore) at the 5% level of significance. This indicates that firms with more board and more audit committee members voluntarily disclosed more information in their annual reports. On the other hand, block ownership and board independence are negatively associated with voluntary disclosure also at the 5% level of significance. This means that firms with a higher ownership concentration and more independent members disclosed less information in their annual reports. As far as the control variables are concerned firm size (SIZE) and auditor type (AUDIT) are positively associated with the extent of voluntary disclosure at the 1% level of significance indicating that larger firms and firms audited by big4 audit firms voluntarily disclosed more information.

The significant positive relationship between the level of disclosure and the size of the board and audit committee, verifies the findings of prior studies which also found a positive relationship (Allegrini and Greco, 2013; Gisbert and Navallas, 2013; Samaha et al., 2015). Supporting the arguments that stem from agency and signaling theory, companies with larger boards and larger audit committees may have disclosed more information in their annual reports to signal to all related parties that they act in line with shareholders’ interests. Although board size has a positive effect on the level of voluntary disclosure, the increase in the number of independent directors has an opposite impact. The presence of more independent members on the board appears to be associated with lower levels of voluntary disclosure, adding new evidence to the controversial results of prior studies on the relation between disclosure and board independence (Eng and Mac, 2003; Allegrini and Greco, 2013; Elfeky, 2017; Shan, 2019). Audit committee independence on the other hand, does not constitute a significant explanatory factor of voluntary disclosure.

Consistent with our expectation from the literature review (Elfeky, 2017; Kolsi, 2017) block ownership constitutes a significant factor of voluntary disclosure, as capital concentrated firms disclosed less voluntary information. This finding supports the argument that in companies with diffused ownership, shareholders may not be an influential factor of corporate reporting practices, due the low level of individual shareholding (Barako, 2006). Contrary to our expectations and even though most of the firms of our sample are family-controlled, family ownership and CEO duality do not exert a significant influence on the extent of voluntary disclosure. Finally, the findings of the study highlight the decisive role that firm size and audit firm type play on voluntary disclosure. Larger firms and firms audited by big4 firms disclosed more information in their annual reports, confirming the results of prior research that has identified them as two of the main factors driving corporate disclosures (Akhtaruddin and Haron, 2010; Patelli and Prencipe, 2007; Allegrini and Greco, 2013; Barros et al., 2013; Scaltrito, 2016; Elfeky, 2017).

Voluntary disclosure is considered as one of the most important mechanisms for the efficient functioning of capital markets, the resolution of conflicts between a company and its related parties and the strengthening of confidence to a company and its governance. The objective of this study was to examine the extent of voluntary disclosure in Greece and assess the disclosure arguments that stem from the theorical framework of corporate governance and focus on ownership, board of directors and audit committee structure. For this purpose, a disclosure index comprising 65 items was constructed and applied on the annual reports of a sample of 93 non-financial companies listed on the ASE. Descriptive statistics show that the average level of voluntary disclosure was relatively low (37.7%) and indicate that listed companies in Greece are reluctant to disclose more information in their annual reports than that required by the regulatory framework.

The study contributes to corporate governance and disclosure literature by providing new empirical evidence on the impact of corporate governance attributes on voluntary disclosure. Consistent with the arguments of agency and signaling theory a significant positive relationship between the extent of disclosure and board and audit committee size was found. This indicates that companies with larger boards and with more audit committee members disclosed more voluntary information in their annual reports. On the other hand, voluntary disclosure was found to be significantly negatively associated with block ownership and board independence, showing that companies with higher ownership concentration and more independent members disclosed less information. Moreover, the findings verify the significant role of firm size and audit firm type on voluntary disclosure. Contrary to our expectations, family ownership, CEO duality and audit committee independence do not appear to exert a significant influence on the extent of voluntary disclosure of listed companies in Greece.

We acknowledge that the study has some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, the study focuses on three main corporate governance attributes: ownership, board of directors and audit committee. Other governance characteristics like gender diversity, financial expertise, remuneration and nomination policy may influence the extent and type of information disclosed in the annual reports. Moreover, the study is limited in one year. Although reporting practices tend to remain relatively stable over time, a comparison of the extent of disclosure could provide useful conclusions. Α significant limitation derives also, from the research instrument. Despite the fact that an unweighted procedure was applied to limit subjectivity into the scoring of the index, subjectivity may have not been fully eliminated, as it is inherent in the scoring process.

The results of the study can be useful to policy makers, supervisory authorities, management, researchers, and all other parties engaged in corporate governance and corporate reporting by providing information regarding the voluntary disclosure of certain items in the annual reports and identifying key governance factors that affect the extent of disclosure. Future research may extend the understanding of the relationship between corporate governance and disclosure by examining more governance attributes and more disclosure items. In addition, it would be extremely interesting to study voluntary disclosures in the context of the conditions created by the coronavirus pandemic. Finally, qualitative research could supplement the findings of this study by providing useful conclusions on the reasons for the high or low voluntary disclosure of certain items of the disclosure index.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Akhtaruddin M, Haron H (2010). Board ownership, audit committees' effectiveness, and corporate voluntary disclosures. Asian Review of Accounting 18(3):245-259.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Alfraih MM, Almutawa AM (2017). Voluntary disclosure and corporate governance: empirical evidence from Kuwait. International Journal of Law and Management 59(2):217-236.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ali A, Chen T, Radhakrishnan S (2007). Corporate disclosures by family firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics 44:238-286.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Allegrini M, Greco G (2013). Corporate boards, audit committees and voluntary disclosure: evidence from Italian listed companies. Journal of Management and Governance 17(1):187-216.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Alshirah MH, Abdul Rahman A, Mustapa IR (2020). Board of directors' characteristics and corporate risk disclosure: the moderating role of family ownership. Euromed Journal of Business 15(2):219-252.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Barako DG, Hancock P, Izan HY (2006). Factors influencing voluntary corporate disclosure by Kenyan companies. Corporate Governance: An International Review 14(2):107-125.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Barros C, Boubaker S, Hamrouni A (2013). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure in France. The Journal of Applied Business Research 29(2):561-578.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bekiaris M (2021). Board structure and firm performance: An empirical study of Greek systemic banks. Journal of Accounting and Taxation 13(2):110-121.

|

|

|

|

|

Boman A, Elvin N (2018). Voluntary disclosure and trust in corporations - A study of listed corporations in Sweden, Dissertation, School of Business, University of Skövde.

|

|

|

|

|

Botosan C (1997). Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review 72(3):323-349.

|

|

|

|

|

Chau GK, Gray SJ (2002). Ownership Structure and Corporate Voluntary Disclosure in Hong Kong and Singapore. The International Journal of Accounting 37:247-265.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chau G, Gray SJ (2010). Family ownership, board independence and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 19:93-109.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chen S, Chen X, Cheng Q (2008). Do family firms provide more or less voluntary disclosure? Journal of Accounting Research 46:499-536.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cohen J, Krishnamoorthy G, Wright A (2002). Corporate governance and the audit process. Contemporary Accounting Research 9:573-594.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Donaldson L, Davis JH (1991). Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management 16(1):49-64.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Doni F, Bianchi Martini S, Corvino A, Mazzoni M (2019). Voluntary versus mandatory non-financial disclosure: EU Directive 95/2014 and sustainability reporting practices based on empirical evidence from Italy. Meditari Accountancy Research 28(5):781-802.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Elfeky MI (2017). The extent of voluntary disclosure and its determinants in emerging markets: Evidence from Egypt. The Journal of Finance and Data Science 3:45-59.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Enache L, Hussainey K (2020). The substitutive relation between voluntary disclosure and corporate governance in their effects on firm performance. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 54:413-445.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eng L, Mak Y (2003). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 22:325-345.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Field A (2018). Discovering Statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics 5th Edition, Sage.

|

|

|

|

|

Fiori G, di Donato F, Izzo MF (2016). Exploring the effects of corporate governance on voluntary disclosure: an explanatory study on the adoption of integrated report. Performance Measurement and Management Control: Contemporary Issues. Studies in Managerial and Financial Accounting 31:83-104.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Galani D, Alexandridis A, Stavropoulos A (2011). The Association between the firm characteristics and corporate mandatory disclosure: The Case of Greece. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology 77:101-107.

|

|

|

|

|

Gaur SS, Bathula H, Singh D (2015). Ownership concentration, board characteristics and firm performance: A contingency framework. Management Decision 53(5):911-931.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gisbert A, Navallas B (2013). The association between voluntary disclosure and corporate governance in the presence of severe agency conflicts. Advances in Accounting 29(2):286-298.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

González JS, García-Meca E (2014). Does corporate governance influence earnings management in Latin American markets? Journal of Business Ethics 121(3):419-440.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gujarati D (2003). Basic Econometrics 4th Edition, McGraw Hill.

|

|

|

|

|

Gul F, Leung S (2004). Board leadership, outside directors' expertise and voluntary corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 23:351-379.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Haddad AE, AlShattarat WK, AbuGhazaleh NM, Nobanee H (2015). The impact of ownership structure and family board domination on voluntary disclosure for Jordanian listed companies. Eurasian Business Review 5(2):203-234.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ho SSM, Wong KS (2001). A Study of the relationship between corporate governance structures and the extent of voluntary disclosure. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 10(2):139-156.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Iatridis G, Rouvolis S (2010). The post-adoption effects of the implementation of International Financial Reporting Standards in Greece. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 19(1):55-65.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Iatridis G, Alexakis P (2012). Evidence of voluntary accounting disclosures in the Athens Stock Market. Review of Accounting and Finance 11(1):73-92.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976). Theory of firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3(4):305-360.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kolsi MC (2017). The determinants of corporate voluntary disclosure policy: Evidence from the Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange (ADX). Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 7(2):249-265.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kourdoumpalou S (2016). Do corporate governance best practices restrain tax evasion? Evidence from Greece. Journal of Accounting and Taxation 8(1):1-10.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Krasodomska J, Michalak J, ?wietla K (2020). Directive 2014/95/EU: Accountants' understanding and attitude towards mandatory non-financial disclosures in corporate reporting. Meditari Accountancy Research 28(5):751-779.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lagasio V, Cucari N (2019). Corporate governance and environmental social governance disclosure: A meta?analytical review. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26(4):1-11.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Leventis S, Weetman P (2004a). Voluntary disclosures in an emerging capital market: some evidence from the Athens Stock Exchange. Advances in International Accounting 17:227-250.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Leventis S, Weetman P (2004b). Impression management: Dual language reporting and voluntary disclosure. Accounting Forum 28:307-328.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Meek GK, Roberts CB, Gray SJ (1995). Factors influencing voluntary annual report disclosures by US, UK and Continental European multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies 26:555-572.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Neifar S, Jarboui A (2018). Corporate governance and operational risk voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Islamic banks. Research in International Business and Finance 46:43-54.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nerantzidis M, Filos J (2014). Recent corporate governance developments in Greece. Corporate Governance 14(3):281-299.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Paape L (2007). Corporate Governance: The Impact on the role, position, and scope of services of the Internal Audit Function. Dissertation, Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM), Erasmus University Rotterdam.

|

|

|

|

|

Patelli L, Prencipe A (2007). The Relationship between voluntary disclosure and independent directors in the presence of a dominant shareholder. European Accounting Review 16(1):5-33.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Patra T, Poshakwale S (2006). Economic variables and stock market returns: evidence from the Athens stock exchange. Applied Financial Economics 16(13):993-1005.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Saha R, Kabra KC (2021). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from India. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting Vol. ahead of print No. ahead of print.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Samaha K, Khlif H, Hussainey K (2015). The Impact of Board and Audit Committee Characteristics on Voluntary Disclosure: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 24:13-28.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sarham AA, Ntim CG (2019). Corporate boards, shareholding structures and voluntary disclosure in emerging MENA economies. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 9(1):2-27.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Scaltrito D (2016). Voluntary disclosure in Italy: Firm-specific determinants an empirical analysis of Italian listed companies. EuroMed Journal of Business 11(2):272-303.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shahrier NA, Ho JSY, Gaur SS (2020). Ownership concentration, board characteristics and firm performance among Shariah-compliant companies. Journal of Management and Governance 24:365-388.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shan YG (2019). Do corporate governance and disclosure tone drive voluntary disclosure of related-party transactions in China? Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 34:30-48.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Skouloudis A, Jones N, Malesios C, Evangelinos K (2014). Trends and determinants of corporate non-financial disclosure in Greece. Journal of Cleaner Production 68:174-188.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tasios S, Bekiaris M (2014). Mandatory disclosures and firm characteristics: evidence from the Athens Stock Exchange. International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting 6(4):303-321.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vadasi C, Bekiaris M, Andrikopoulos A (2021). Internal Audit Function Quality and Corporate Governance: The Case of Greece. Multinational Finance Journal 25(1/2):1-61.

|

|

|

|

|

Zhou C (2019). Effects of corporate governance on the decision to voluntarily disclose corporate social responsibility reports: evidence from China. Applied Economics 51(55):5900-5910.

Crossref

|

|