Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

While revisiting the agency theory and how it models the relationship between a principal and an agent, we assess, through participant observation, the optimal contract form for the ubiquitous relationship, where a principal, delegates work to an agent. This forms the basis of the study, as it attempts to redefine the relationship between the taxpayer and the tax administrator. This research is an attempt to reverse the traditional relationship between the taxpayer and the tax administrator in favor of a modern perspective of relational model theory by seeing the taxpayer as the principal and the tax administrator as the agent. This is deeply rooted in the social contract theory, in relation to the agency theory. What this redefinition is expected to do, ultimately, is to make the tax authority more taxpayer centric based on the concept of trust breeds trust, for efficient and effective tax system that would be more accountable, transparent and responsible in service delivery in the 21st century. This paper draws from the application of the social contract theory and the empirical evidences obtained from participant observation in the form of improvement of service delivery to the taxpayers by the tax administrators in the experimental agency, in alignment with the agency theory, hence coming up with the ‘relational agency model’.

Key words: Taxpayer, tax administrator, agency theory, social contract, relational theory, relational agency model.

INTRODUCTION

In Nigeria, and like everywhere else, the taxpayers are the single most important group of stakeholders in the tax system. They are so important that they are recognized in the National Tax Policy Document of Nigeria (2012) and the revised National Tax Policy Document (2017). Even though taxpayers’ responsibilities are fundamental to the functioning of a viable tax system, they must be balanced with taxpayer rights in an equitable and justifiable manner, as trust breeds trust (Feld and Fray, 2002; Olokooba et al., 2018).

It is important to note that a taxpayer is an important variable in the achievement of the objectives of a Tax (Revenue) Authority. Based on this position, it is proper to define who a taxpayer is. Drawing from previous studies, a taxpayer is anyone who is subject to tax on income, irrespective of whether he pays the tax or not. The taxpayer may be an individual, company or organization liable to pay tax (Somorin, 2012; Olokooba, 2019). The individual taxpayer is traditionally seen as a resident in a society, who must be an adult of taxpaying age, earning one source of income or another that is not exempted from income tax, and can be subjected to tax deduction. In the same manner, organizations operating within the society are equally required to pay taxes on income and profits generated in the process of their business operations. However, the not-for-profit organizations are exempted from tax provided certain conditions are fulfilled.

Having define who a taxpayer is, it is of equal importance to explain further what the taxes paid are meant for. The taxes paid by the taxpayers to the authorities of government saddled with the responsibilities of collecting such, are therefore expected to be used in return by the government to provide social and economic infrastructure (facilities) for the benefit of the people in the society, whether taxpayer or not (Awodun, 2018a). This position is based on the social contract theory as enunciated by Bruner (2015), Cook and Dimitrov (2017), Bussolo et al. (2018) and El-Haddad (2020).

The scenario painted above draws a relationship between the taxpayer, the tax authority and the government, following the relational model theory (Haslam and Fiske, 1999). This relationship has been seen from different perspectives in the course of fulfillment of the obligations of the various parties in the past. What is common perspective in Nigeria is to see the tax authority as an agency of government saddled with the responsibilities of collecting taxes from the taxpayers. This is a rather conventional viewpoint. Right as this perspective may be, the emphasis placed on this relational view has given less attention to the other perspectives, and perhaps the reason for the high level of inefficiency of the tax system and low level of compliance of the taxpayers (Hofmann et al., 2014).

One of such other perspective, given less or no consideration, is the relationship between the taxpayer and the tax authority, which has not been properly defined. What we observe is that the tax authority relates with the taxpayers under a lord and master (command) relationship with the understanding that the tax authority, a product of law, is empowered to enforce and apply the law on the taxpayers to extract the due taxes from them (Kirchler and Wahl, 2010).

This approach has proven to be not so effective, with taxpayers devising methods of averting and avoiding the payment of taxes as a result of this approach (Allingham and Sandmo, 1971; Andreoni et al. 1998; Alm and Torgler, 2006; 2011).

However, under close observation, the researchers realize that the taxpayers and the tax authority should operate under a better relational perspective based on the combined understanding of the agency and social contract theories.

This perspective called on the ‘relational agency model’. In examining how taxpayers are treated, the concept of trust breeds trust as put across by Feld and Frey (2007) became relevant. This is because the taxpayer, under this ‘relational agency model’ is in a contractual relationship with the government, on whose mandate the tax authority operates, to collect taxes from the taxpayers, and use such taxes to provide social infrastructure and services for the benefits of all members of the society (both taxpayers and non-taxpayers) within the context of the social contract theory (Awodun, 2016).

The above, therefore, justifies the need to revisit the relationship between these players in the tax system and perhaps come up with an alternative perspective that could exert better result than what we have today. The quest of the study is to redefine the relationship between the taxpayers and the tax authorities in the country with the sole purpose of eliciting a more acceptable outcome to all parties’ concern, hence the development and application of the ‘relational agency model’.

Background to the taxpayer/tax administrator relationship

Searching the literature on taxpayer and tax administrator relationship in Nigeria, the very first time attention was focused on taxpayers in the history of the Nigerian tax system was found in Paragraph 4.11 page 44 of the Report of the Task Force on Tax Administration (1979) where the following recommendation was made:

More publicity should be given to taxpayers about what they are expected to do to satisfy their tax obligations. Similarly, government should mount special publicity programmes aimed to enlighten taxpayers on the use of tax revenue.

The report brought to bear for the first time, the need to sensitize the taxpayers about their civic responsibilities in the form of tax education and enlightenment. In addition, it encouraged government on accountability and transparency on the application of the funds collected as taxes from the taxpayers. The purpose of these two recommendations is obviously to ensure improvement in the level of taxpayer compliance with ultimate increase in taxes collected.

From a critical examination of who a taxpayer is, there are some characteristics that can be deduce which will determine whether an individual is qualified to be regarded as a taxpayer or not. First, is the residency clause that requires the taxpayer to be resident within the society in question? This condition is important and has been discussed in several literatures. The second is adulthood which means that the taxpayer must have attained the tax paying age as contained in the tax laws. The third is that the taxpayer must have at least a source of income (above ?30,000 per month for individuals in Nigeria) from which the tax due could be deducted, and (annual income in excess of ?25 million for companies, in Nigeria).

All of the above are as contained in the tax laws of the society in question, as collection of taxes is based on statute. The power or authority to collect taxes is rested on the government, who in turn establishes an agency to exercise this authority or power on its behalf as stipulated in the tax laws that the government may legislate from time to time. Based on the above, the taxes collected are not arbitrary as they are well spelt out, and the basis of introduction of such taxes also, are well considered and communicated.

The agency established by the government to collect the taxes, as stipulated by law, from the taxpayers, normally regarded as the tax authority, is the tax administration arm of government, and the operators engaged by the agency are the tax administrators. Furthermore, Chapter 3, Paragraph 3.2(v) of the National Tax Policy (2012) also states that a taxpayer is entitled to self-representation or representation by any agent of choice, provided the agent, acting for financial reward, shall be an accredited tax practitioner.

It is, therefore, common for the agency of government (tax authority) and the tax administrators, engaged by the government agency, to see themselves as empowered, by the law establishing them, to enforce compliance to the tax laws (National Tax Policy, 2017). Trust in authorities and power to enforce tax compliance (Wahl et al., 2010) is expressed in why people obey the law (Tyler, 2006) and the detrimental nature of the inconsistencies in punishment procedures to compliance (Van Prooijen et al., 2008). The tax administrators go about the discharge of their responsibilities of assessing, collecting, accounting for taxes as backed up by the laws and conduct their affairs of tax administration from this point of view.

Income tax evasion is a global phenomenon (Allingham and Sandmo, 1971) whose justification and the administrator’s tax compliance struggle are based on ethics, morality, power and law under the social contract theory perspective (Alm and Torgler, 2011; El-Haddad, 2020). Where necessary, the administrators may enforce tax collection from deviant taxpayers using the instrumentality of law. It is not strange, therefore, to observe compliance being achieved mostly through enforcement by the tax agency (Muehlbacher and Kirchler, 2010). This is drawn from the conventional perception that the tax administrators see themselves as an agency of government, empowered by law to bring about the enforced collection of taxes from the residents (individuals) and companies operating in the society under its coverage (Alm and Torgler, 2006; Blackwell, 2007; Somorin, 2019).

The basis of the above position is that the taxpayer is seen as that individual or organization whose income is the subject of tax deduction, will rather do everything to evade paying taxes so as to keep all his income. With this perception, the agency empowered by law, therefore, believes that compliance could be attained through enforcement, if the taxes due to government are to be extracted appropriately from the taxpayer. The tax agency, based on this perception, assumes the position of a government agency from the conventional point of view, playing the traditional role of enforcing the collection of taxes from the taxpayers.

Research problem, hypothesis and model

When the fact that the concept of tax, ordinarily is considered based on the social contract theory (El-Haddad, 2020; Healy and Murphy, 2017) where the residents only surrender their sovereignty to the state to administer their collective affairs in return for the payment of taxes, then the agency relationship of the tax authority would need a revisit, and the relationship between the taxpayer and the tax administrator, a redefinition. This is because rather than the tax agency, whose activities are carried out through the tax administrator, being seen as the agent of the state, this study proposes that a different consideration is given to that relationship based on the concept of the agency theory without undermining the convention.

This approach, as proposed, would see the tax agency, from the ‘relational agency model’ perspective, as an agency of the taxpayer instead of the traditional perspective of being the agency of government. This is because the state is merely a custodian of the collective sovereignty of the residents of the state which is voluntarily surrendered to it. The relational theory (Haslam and Fiske, 1999; Cook and Dimitrov, 2017; Feldmann and Mazepus, 2018) further supports the above position. The people are the constituent of any state, and it is because they have given up their individual sovereignty, in the first instance, that is why the state could entrust the tax authority with the responsibility of tax collection. Hence, the tax authority is better seen as the agency of the people than the agency of the state.

The problem of this study is, therefore, a redefinition of the relationship between the taxpayer and the tax administrator by subjecting it to the test of the triangular ‘relational agency model’ within the context of agency theory, social contract theory and relational model theory. This is being examined from the perspective of the economic psychology of tax behavior (Kirchler, 2007). By so doing, it is expected that the administrator understands the redefinition of their relationship, and the realignment of the tax authority’s operational activities in compliance to this perspective, would ultimately bring about optimum tax collection.

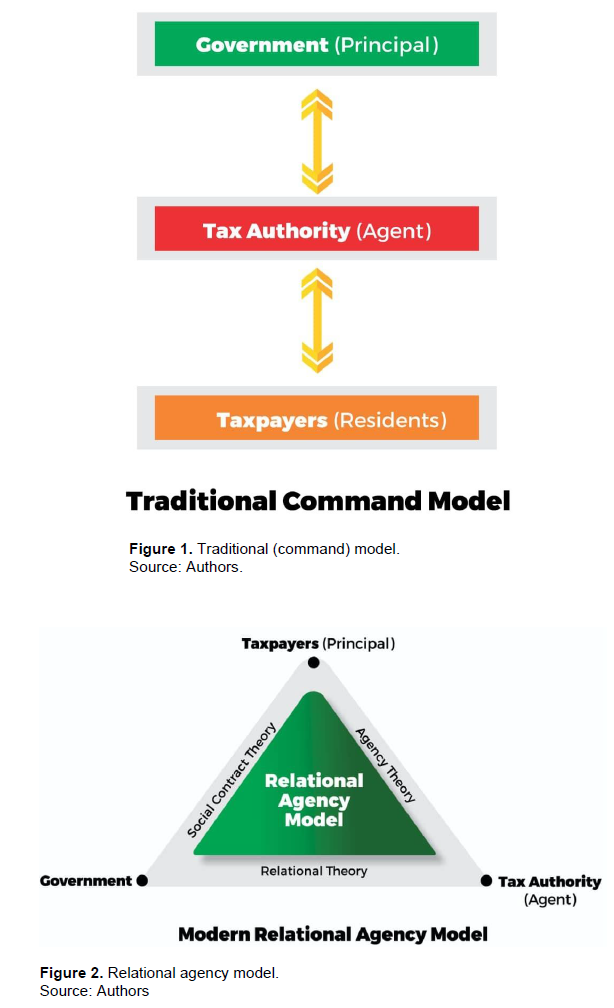

The traditional command approach is a top to bottom model that depicts the government as the principal in the taxpayer relationship management, and the tax authority as the agent. The taxpayer is described to be at the bottom of the ladder and expected to comply strictly with the commands of the government through the tax authority as depicted in Figure 1. Under this approach not much concern and attention is given to the taxpayer beyond the expectation to comply with the payment of taxes through the tax authority.

However, the relational agency model approach is a triangular arrangement that puts the taxpayers as the principal under the agency theory, while the tax authority is the agent. The taxpayers and government come into a relationship under the social contract theory. The tax authority and the taxpayers are also within the relational theory expected to have cordial relationship within the taxpayer relationship management process. The situation as described above forms the basis of what is depicted appropriately in Figure 2 as the relational agency model, the application of which is the basis of this study.

We therefore hypothesize that the taxpayers are more responsive and compliant where and when they are seen and treated by the tax administrators as their principal, as express by the relational agency model than where and when they are seen as subservient residents in the traditional (command) model.

Conceptualizing the ‘relational agency model’ within the context of the agency, relational and social contract theories

The agency theory models relationship between a principal and an agent, considers the optimal contract form for the ubiquitous relationship where a principal, delegates work to an agent (Eisenhardt, 1989; Awodun, 2018b). Agency theory is built on the notion that separation of ownership and control potentially leads to self-interested behaviors by the agent (Kirchler, 2007;. Kirchler et al., 2008). Testing the ‘slippery slope’ framework in Austria, Hungary, Romania and Russia, Kirchler and Wahl, (2010) and Kogler et al. (2013) revealed that trust and power are the determinants of tax compliance

In agency theory, both the principal (that is, shareholders) and the agent (that is, managers) are depicted as utility maximizers (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Fama and Jensen 1983). The agent’s utility function includes power, security, status, and wealth while the principal’s utility function is to maximize the market value of their shares or interests or stakes as the case may be (Awodun, 2018b). The taxpayer’s tax compliance, coercion and legitimate power of tax authorities are as a result of diminishing trust in tax authorities (Hofmann et al., 2014).

Agency theory has witnessed such rigorous research with contributions by researchers such as Berle and Means (1932), Fama and Jensen (1983); and Jensen and Meckling (1976) directed at a particular type of organizing problem, called agency problem (Eisenhardt, 1989). In agency theory literature, the primary agency problems, popularly considered are; moral hazard (MH) and averse selection (AS) (Eisenhardt, 1989). Moral hazard is a problem resulting from the situation where the principal cannot observe or monitor the agent’s actions. Arrow (1985:37) says that the problem here arises when “the agent’s action is not directly observable by the principal.”

Averse selection (AS), on the other hand, is a problem resulting from the situation where the principal cannot assess whether the agent’s actions best serve the principal’s interests. Arrow (1985) opined that the problem, in this situation, arises when “the principal may be able to observe the action itself, but does not know whether it is the most appropriate one.” In other words, the principal cannot ascertain whether the agent is protecting his interest or not, despite being able to observe the activities of the agent.

According to Mitnick (1994), the critical difference between moral hazard and averse selection is that the former principal cannot observe the agent’s actions, giving the agent the latitude to take actions that have undesirable consequences for the principal. While in the latter, the principal may well observe the agent’s actions, but the principal cannot tell whether the agent’s actions are optimal with respect to the principal’s interests. Thus, it is quite conceivable that agency problems could be aggravated if it becomes more difficult for the principal to observe and appraise what the agent is actually doing and has done for the principal.

Agency theory is considered appropriate to situations that have a principal-agent structure. In specific terms, it is popularly related to the headquarters-foreign subsidiary relationship in multinational enterprises where it is applied to the situation of principal agent structure, as the headquarters, delegates’ decision-making authorities and responsibilities to foreign subsidiaries (Gupta and Govindarajan, 1991; Nohria and Ghoshal, 1994; Roth and O’Donnell, 1996; Bonazzi and Islam, 2007). Though the situation under consideration is not similar, however, the extent of difficulty to which the principal (that is, the headquarters) faces in the observation and verification process could be dependent upon the strategic roles of the agent (that is, foreign subsidiaries), and is relevant in this case. Foreign subsidiaries will cast different levels of agency problems to the headquarters depending on the strategic role they are undertaking – that is, specialized contributors, local implementers, and world mandates (Kim et al., 2005) just as the taxpayers constitute different problems to the tax authority whether as individual or corporate taxpayer.

The agency theory substantiates most of these arguments on efficient governance. Considering that the corporation is a bundle of contracts, the contract between managers and shareholders is not different from the contracts between the other agents involved in the value-adding activities (employees, customers, suppliers). Investors as owners of stock in the stock market capitalism delegate decision-making powers to agents (managers and independent directors). The taxpayers, in the same manner should be seen as the owners of the tax authority, particularly from the perspective of the social contract theory, in support of the above agency theory position.

Ultimately, agency costs rise not only because of opportunistic behavior by managers, but also from the monitoring and control mechanisms put in place by stock-holders (Awodun, 2018b). The entire corporate governance system put in place to protect investors’ interest, represent an institutionalization of monitoring and control procedures, raising costs, and diminishing allocative efficiency. Hill and Jones (1992) summarize three sources of agency costs from the perspective of agency theory: (a) principal’s monitoring expenditure; (b) agents’ bonding expenditure; and (c) residual loss.

What can be deduced from all of the above reviews are that the taxpayer is, indeed, the principal in our consideration of applying the ‘relational agency model’ to tax administration, while the tax administrator is the agent. This position does not discard the already established agency relationship between the government and the tax authority which is another line of relationship. It also does not eliminate the agency relationship between the tax authority and the employees (tax administrators). While the first is the new consideration the researchers are focusing attention on in this research, the other two relationships have been well established in several other research. Therefore, the outcomes of the application of the ‘relational agency model’ were presented to the relationship between the taxpayer and the tax administrator in an attempt to redefine this relationship, as indicated in the objective of this study.

RESEARCH METHOD

The methodology of research adopted by this study is participant observation, where the main researcher was involved in the operational activities of a State Internal Revenue Service in the North Central Region of Nigeria for 48 months between 2015 and 2019. Putting across his theoretical observation of the perception of tax administrators and taxpayer relationship, as against the conventional perception, prior to his engagement in the organization, he set out to experiment the new theoretical stand with the commencement of activities of the Agency in October, 2015.

The various top management staff were the first to be sensitized on the need for this experimentation with clearly defined strategic objectives and values for the Agency built around this new paradigm. With the resolve of the top-level management to travel this new road together, the middle level management was brought on board, a month later. The low-level management was the last to be introduced into this paradigm change, and that was achieved through an intensive training that commenced, three months after the commencement of activities. Thus, the experimentation proper started from the first month of 2016.

With the core values of service, honesty, integrity, responsibility and trust, acronym ‘SHIRT’, the entire 147 staff members, that commenced full operations in January 2016, were appropriately sensitized on the ‘relational agency model’ perspective of the tax authority as the agent of the taxpayer based on application of the agency theory to the taxpayer relationship management. The Agency created a taxpayer centric perspective, and in 48 months of operations, applied this new paradigm in its taxpayer relationship management.

Applying the ‘relational agency model’ in redefining the relationship between the tax administrator and the taxpayer

Arising from the description of the ‘relational agency model’ above and from the understanding of rethinking the social contract theory (Bussolo et al., 2018; Bussolo et al., 2019), it can be safely said that the taxpayer in every society is the principal, in this relationship, and the tax authority is the agent. Though, representing the state in the administration of taxes in the society, the tax authority and the state are one, and on the same side of the divide in this relationship, while the taxpayer is on the other side.

As we have established from the social contract theory earlier in Bruner (2015) and El-Haddad (2020), the taxpayers are the collective owners of the resources of the state, but have only appointed the government to manage these resources on their behalf, thus, surrendering their individual rights to the state. The state, in return, had thought it wise to subject every resident to paying a part of their earned income as taxes for them to be able to carry out the administration of the collective resources of the state on behalf of the residents (taxpayers), and for redistribution of income and wealth in the society.

One of the problems encountered, and arising from the application of the ‘relational agency model’ to the taxpayer and tax administrator relationship, called taxpayer relationship management, is the ‘moral hazard’ problem which is as a result of the fact that the principal, in this case, the taxpayers, cannot observe or monitor the agent (tax authority)’s actions. As rightly observed by Arrow (1985), this problem arises because “the agent’s action is not directly observable by the principal.” This situation is the situation that most of the tax authorities had exhibited because they have not rightly seen the taxpayer as their principal under the command (traditional) perspective, and as such do not see themselves as accountable to them. They had rather, on the contrary, believed that they are accountable to the government only, failing to realize that the government are merely representing the taxpayers in the administration of the collective resources of the state.

To address this problem, in the course of experimentation, the researchers subscribed to a reporting mechanism that mandated the agency to report publicly, through various medium, the activities, operations and performance of the tax authorities on a monthly basis through the local media, and a quarterly media parley. By so doing, it became more accountable and responsible to the taxpayers, as our principal, based on the ‘relational agency model’ perspective adopted in taxpayer relationship management.

Another problem arising from the application of the ‘relational agency model’ to the taxpayer and tax authority relationship is averse selection’. This is a problem that results from the situation where the principal (in this case, the taxpayer) cannot assess whether the agent’s actions best serve his interests. Arrow (1985) also noted that this problem arises as a result of the principal, being able to observe the action of the tax authority, but does not know whether these actions are the most appropriate, and in their best interest or not.

To address this observed problem, an infrastructure fund mechanism was also fashioned out with the government where a substantial portion of the taxes collected monthly is legislated to be accrued in an infrastructure fund account and utilized specifically for social infrastructure projects that could be considered as ‘common good’ for the benefit of the society. This infrastructure funding mechanism commenced in October 2016, exactly a year after the commencement of operations of the experimentation.

While in the ‘moral hazard’ problem, the taxpayer, as the principal, cannot observe the agent’s actions, thus, allowing the agent to take actions that have undesirable consequences for the principal, in the ‘averse selection’ problem, however, the taxpayer may well be able to observe the agent’s actions, but cannot tell whether the agent’s actions are optimal with respect to his interest or not.

Thus, it is quite conceivable that agency problems could be aggravated if it becomes more difficult for the principal to observe and appraise what the agent is actually doing or has done for the principal. This is the situation that most of tax authorities face with the taxpayers who are growing more enlightened and more educated. Unlike when the taxpayers were very uneducated and cannot express their rights, the situation today is that the taxpayers are now better informed, with the advent of technology, and therefore, subtly demanding for their rights as the principal in their relationship with the tax authority.

The outcome of this experimentation over a period of 48 months, in the case of the State IRS observed revealed that the earlier the tax authorities begin to understand the relationship between them and the taxpayers and relate with the taxpayers from this point of understanding, the better will be their performances. In other words, the taxpayers should be given more and better attention as tax authorities must be more taxpayer centric than they have ever been in their taxpayer relationship management. This is what the relational agency model is all about.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The findings show that the traditional (command) approach to tax administration cannot be sustained in this modern day for so many reasons, and this has form the basis of our call for a redefinition of relationships, particularly that between the taxpayer and the tax authorities. This paper has subjected that relationship to the agency theory to redefine the relationship such that the taxpayer is now seen as the principal and the tax authority as the agent. To further understand this position, the tripod of the agency, relational and social contract theories came handy. This redefined triangular ‘relational agency model’ approach, when subjected to test at the tax authority of our choice, was able to change the dynamics of tax administration positively, as it was given due consideration by the Agency.

What we observe in the course of the study is that a redefinition of the relationship resulted in giving more attention to the taxpayers who are the customers of the tax agency, on one hand, and the owners of the tax agency on the other hand. The moment, the tax authority, resolve to begin to see the taxpayers from this perspective, consideration for better service and responsible delivery of such service became of topmost priority to the tax administrators. The tax authority, thus, began to think in terms of the taxpayer’s convenience in the course of rendering their service, with the provision of convenient and more efficient tax administration mechanisms, and this resulted in optimal performance.

The ultimate purpose of a tax authority is the growth of taxes collected. In our experimentation of measuring the paradigm change against the internal revenue performance, the researchers observe that the internally generated revenue of the State IRS grew from N7.2 billion in 2015 to N17.4 billion in 2016, N19.6 billion in 2017, N23.1 billion in 2018 and N30.1 billion in 2019 when the experimentation was concluded. The significance of the change in the taxpayer relationship management with the application of the ‘relational agency model’ was felt at the bottom line of the Agency.

Also of significance is the aspect of accountability and transparency which was noted, as not only required for the purpose of satisfying the taxpayers as the principal, but also as a means of eliciting taxpayer’s confidence with the possibility of bringing about more voluntary compliance. This also boosted the effectiveness of the tax authority through increase in the level of compliance, as registered taxpayers grew from 11,217 in 2015 to 52,411 in 2016, 61,233 in 2017, 100,972 in 2018 and 155, 298 in 2019. There is also the aspect of taxpayers’ engagement that complements the responsibility of the tax authority in delivering openness to the principal (the taxpayers) in the tax collection relationship.

In conclusion, the ‘relational agency model’ suggests that corporate governance can reduce agency costs, which in turn leads to improved firm performance. The problem inherent in the failure to do this is known as the principal-agent problem between two parties, the principal and the agent. As concerning corporate governance in multinational enterprises, like in the domestic firms, it involves separation of ownership and control, and this, as far as the open financial system is concern, can resolve the agency problem between management and shareholders. Openness in rendering account of collection of taxes such that all taxpayers can have access to amounts collected is not negotiable in this redefine relationship between the taxpayer and the tax authority.

Finally, is the process improvement that was embarked upon through international standardization, and adoption of technology in the operations of the tax authorities to make service delivery more efficient and effective. This, though a herculean task, because of the resistance to change of the people, was combined with the training and retraining of the tax administrators to re-orientate them appropriately in this new direction that the world of tax administration is moving towards. It made the taxpayer relationship management, under the new model, effective. Based on the above outcomes, over the period of experimentation, we came to that conclusion that the taxpayer should be seen as the principal in the taxpayer and tax authority relationship as professed by the ‘relational agency model’.

CONCLUSION

The tax administrators of the 21st century will be able to make significant difference in their performances, if and when there is a very clear understanding of the basis of their relationship with the taxpayers, as redefined in this paper. The taxpayer, who is seen as the target of fulfillment of the responsibilities of the tax authority, is more importantly the principal in the relationship with the tax authority, and what this means is that they have far more expectations from the tax administrators under the ‘relational agency model’ approach than under the command (traditional) approach.

While the taxpayers are expected to fulfill their obligations of tax payment, the tax administrators have relegated to the background the very important responsibilities expected by the taxpayers also from them. Fulfilling these contractual responsibilities of accountability, service, and transparency, with understanding, will go a long way to make the taxpayers commit to voluntary tax payments than ever, and raise the bar of tax compliance. To make this possible, the tax authorities should begin to think of the taxpayers as their customers, and their shareholders, who will require from them service and accountability, for them to remain relevant in their taxpayer service delivery.

The above, therefore, affirms the significance of our ‘relational agency model’ as a more effective and efficient approach to taxpayer relationship management than the traditional (command) approach.

FURTHER RESEARCH

Following the observed outcomes of this study, and the significance of the performance, it is hereby suggested that the results of performance could be further subjected to a quantitative analytical methodology that would recognize all other factors beyond this ‘relational agency model’ as responsible for the positive results. Some of these factors are already captured and discussed in this study while some others have been left out. However, a quantitative study that would capture all determinants of the positive results of the experimental period will capture the various contributions of all the factors, and provide further insight into the application of this ‘relational agency model’ to the relationship between the taxpayer and the tax administrator.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Allingham MG, Sandmo A (1971). Income tax evasion: a theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics 1(3-4):323-338. |

|

|

Alm J, Torgler B (2006). Culture differences and tax morale in the United States and in Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology 27(2):224-246. |

|

|

Alm J, Torgler B (2011). Do ethics matter? Tax compliance and morality. Journal of Business Ethics 101(4):1-17. |

|

|

Andreoni J, Erard B, Feinstein J (1998). Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature 36(2):818-860. |

|

|

Arrow KJ (1985). The economics of agency. In: Pratt JW, Zeckhauser RJ (eds.). Principals and agents: The structure of business, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. pp. 37-51. |

|

|

Awodun MO (2016). Taxpreneurship: A revolutionary paradigm for improving internally generated revenue in Kwara state, Nigeria. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Management. Kwara State University Centre for Entrepreneurship 1(1):314-332. |

|

|

Awodun MO (2018a). Taxpreneurship, Dubai Printing Press, UAE. |

|

|

Awodun MO (2018b). Managing domestic and multinational enterprises in emerging markets. Dubai Printing Press, UAE. |

|

|

Blackwell C (2007). A meta-analysis of tax compliance experiments. International Studies Program Working Paper, 7, 24. |

|

|

Bonazzi L, Islam SMN (2007). Agency theory and corporate governance: A study of the effectiveness of board in their monitoring of the CEO. Journal of Modelling in Management 2(1):7-23. |

|

|

Bruner JP (2015). Diversity, tolerance and the social contract. Politics, Philosophy and Economics 14(4):429-448. |

|

|

Bussolo M, Lopez-Calva LF, Sundaram R (2018). Leveling the playing field: Rethinking the social contract in ECA. The World Bank, Washington DC. |

|

|

Bussolo ME, Davalos V, Peragine R, Sundaram R (2019). Towards a new social contract: Taking on distributional tensions in Europe and Central Asia. The World Bank, Washington DC. |

|

|

Cook L, Dimitrov M (2017). The social contract revisited: Evidences from communist and state capitalist economies. Europe-Asia Studies 69(1):8-26. |

|

|

El-Haddad A (2020). Redefining the social contract in the wake of the Arab Spring: The experiences of Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia. World Development 127:104774. |

|

|

Eisenhardt KM (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review 14(1):57-74. |

|

|

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983). Separation of ownership and control. Journal of Law and Economics 26(2):301-325. |

|

|

Feld LP, Frey BS (2002). Trust breeds trust: how taxpayers are treated. Economics of Governance 3(2):87-99. |

|

|

Feld LP, Frey BS (2007). Tax compliance as the result of a psychological tax contract: the role of incentives and responsive regulation. Law and Policy 29(1):102-120. |

|

|

Feldmann M, Mazepus H (2018). State-society relations and the sources of support for Putin regime: Bridging political culture and social contract theory. East European Politics 34(1):57-76. |

|

|

Gibson R (1998). Rethinking business. In Gibson R (ed.) Rethinking the future, Nicholas Brealey, London, UK, pp. 1-14. |

|

|

Haslam SA, Fiske AP (1999). Relational model's theory: a confirmatory factor analysis. Personal Relationships 6(2):241-250. |

|

|

Healy S, Murphy E (2017). Reconnecting people and state: Elements of a new social contract. In Reynolds B, Healy S (eds.) Society matters: Reconnecting people and state. Social Justice Ireland, Dublin, Ireland, pp. 1-28. |

|

|

Hill C, Jones T (1992). Stakeholder-Agency theory. Journal of Management Studies 29(2):134-154. |

|

|

Hofmann E, Gangl K, Kirchler E, Stark J (2014). Enhancing tax compliance through coercive and legitimate power of tax authorities by concurrently diminishing or facilitating trust in tax authorities. Law and Policy 36(3):290-313. |

|

|

Gupta AK, Govindarajan V (1991). Knowledge flows and the structure of control within multinational corporations. Academy of Management Review 16(4):768-792. |

|

|

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3(4):305-360. |

|

|

Kim B, Prescott JE, Kim SM (2005). Differentiated governance of foreign subsidiaries in transnational corporations: An agency theory perspective. Journal of International Management 11(1):43-66. |

|

|

Kirchler E (2007). The economic psychology of tax behaviour. University Press; Cambridge. |

|

|

Kirchler E, Hoelzl E, Wahl I (2008). Enforced versus voluntary tax compliance: the "slippery slope" framework. Journal of Economic Psychology 29(2):210-225. |

|

|

Kirchler E, Wahl I (2010). Tax compliance inventory TAX-I: designing an inventory for surveys of tax compliance. Journal of Economic Psychology 31(3):331-346. |

|

|

Kogler C, Batrancea L, Nichita A, Pantya J, Belianin A, Kirchler E (2013). Trust and power as determinants of tax compliance: testing the assumptions of the slippery slope framework in Austria, Hungary, Romania and Russia. Journal of Economic Psychologie 34:169-180. |

|

|

Mitnick B (1994). The hazards of agency. Paper presented in the 1994 Annual Meetings of the American Political Science Association, New York Hilton. |

|

|

Muehlbacher S, Kirchler E (2010). Tax compliance by trust and power of authorities. International Economic Journal 24(4):607-610. |

|

|

National Tax Policy (2012). Federal Ministry of Finance, Nigeria. |

|

|

National Tax Policy (2017). Federal Ministry of Finance, Nigeria. |

|

|

Nohria N, Ghoshal S (1994). Differentiated fit and shared values: Alternatives for managing headquarter-subsidiary relations. Strategic Management Journal 15(6):491-502. |

|

|

Olokooba SM, Awodun MO, Akintoye OD, Abubakar SA (2018). Taxpayer's right to refund under the Nigerian law: A right in fact or privilege in camouflage? Nnamdi Azikiwe University Journal of International Law and Jurisprudence 9(2):192-198. |

|

|

Olokooba SM (2019). Nigerian taxation: Law, practice and procedure simplified. Springer Nature, Switzerland. |

|

|

Report of the Task Force on Tax Administration in Nigeria (1979). Federal Government Printing Press, Lagos, Nigeria. Available at: |

|

|

Roth K, O'Donnell S (1996). Foreign subsidiary compensation strategy: An agency theory perspective. Academy of Management Journal 39(3):678-703. |

|

|

Somorin O (2012). TEJUTAX reference book, on the Nigerian tax system, general terms. Lagos 1 & 2. |

|

|

Somorin OA (2019). Taxpayers: Voices, disconnect and tax compliance. Caleb University 4th Inaugural Lecture, Lagos, Nigeria. |

|

|

Tyler TR (2006). Why people obey the law. Princeton University Press; Princeton, USA. |

|

|

Van Prooijen JW, Gallucci M, Toeset G (2008). Procedural justice in punishment systems: Inconsistent punishment procedures have detrimental effects on cooperation. British Journal of Social Psychology 47(2):311-324. |

|

|

Wahl I, Kastlunger B, Kirchler E (2010). Trust in authorities and power to enforce tax compliance: an empirical analysis of the "Slippery Slope Framework. Law and Policy 32(4):383-406. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0