Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This study aims to assess the effectiveness of alternative monetary policy transmission channels in Tanzania. Theoretically, monetary policy transmission is expected to differ between developed and developing countries due to varied structural and institutional features. The empirical work undertaken by this study suggests that the sensitivity of output and prices to changes in monetary policy are generally weak and slow. Moreover, the study found a significant contribution of monetary policy in explaining the dynamics of the supply of credit to the private sector which matters in fostering the growth of the economy. And lastly, it appears that inflation and exchange rate dynamics in Tanzania are highly influenced by developments in international oil prices. There are potentially three policy implications, the first one being sustaining financial sector reforms geared towards eliminating the remaining structural impediments that hinder financial deepening, the Bank may choose to switch to an alternative monetary policy framework that has proved to be successful in attaining price stability, the Bank of Tanzania should continue with close monitoring of the global developments especially the movements in the international oil prices and react appropriately to safeguard the domestic macroeconomic stability.

Key words: Monetary policy, central banks and their policies.

INTRODUCTION

The concern about the impact of monetary policy on the economy has received enormous attention in macroeconomic theory and among central banks in the world. It is generally agreed that the monetary policy affects output and prices by influencing key financial variables such as interest rates, exchange rates and monetary aggregates (Mishkin, 1996).

Changes in monetary policy are “proliferated” through the economy by means of a transmission mechanism, normally referred to as the monetary transmission mechanism.

Since 1995, the Bank of Tanzania implements a monetary policy framework that is directed towards attaining low (Low and stable inflation is defined as inflation of 5.0 percent in the medium term) and stable inflation (price stability) conducive to the balanced and sustainable growth of the economy (Bank of Tanzania (BOT) Act, 2006). In the current framework, the Bank targets monetary aggregates (the extended broad money-M3) as a nominal anchor (Reserve money or base money is used as operational/policy variable in realizing extended broad money targets) in attaining the policy objectives. However, the Bank is currently contemplating moving into the inflation-targeting framework (The move is also justified by the unstable money demand following financial innovations) as part of its commitment to the implementation of the East Africa Monetary Union (EAMU) Protocol (Bank of Tanzania (BOT), 2018).

It is widely acknowledged that changes in the structure of the economy tend to alter the effectiveness of a given monetary policy transmission mechanism (Carranza et al., 2010; Mishra et al., 2012; Ma and Lin, 2016). There have been enormous developments in the financial sector in Tanzania, especially since the 2000s that were brought about by financial innovations mainly related to developments in payments systems and financial markets developments such as the introduction of new financial instruments. All these have enhanced the financial inclusion that involves an increase in access and usage of financial services (FSDT, 2017). These financial sector developments are expected to be sustained and ultimately impact the transmission mechanism of the monetary policy in Tanzania, either by changing the overall impact of the policy on key macroeconomic variables or by altering the channels through which it operates.

Similarly, the insensitivity of lending rates to changes in a monetary policy stance that has been observed in Tanzania together with the recent declinein the growth of credit to the private sector despite monetary policy easing makes it important to re-assess the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission mechanisms to key macro-economic variables.

Along the same line, the decision by the EAC central banks to adopt the Monetary Union (EAMU) by 2024 makes it relevant for the central banks in the block to undertake a regular assessment of the effectiveness of the monetary policy transmission mechanism in their respective countries for harmonization of the monetary policies with the appropriateframework.

In studying the monetary policy transmission mechanism two key issues usually emerge including, the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission channels such as money/interest rate, credit, exchange rate and asset price in transmitting policy shocks to output and prices as well as the timing and magnitude of the effects of the monetary policy shocks on selected macroeconomic variables. This is what Mishkin (1995) called the ‘timing and effect’ of monetary policy in the economy.

In the case of Tanzania, several studies on the monetary policy transmission have been conducted and yielded some conflicting views but agreed on the weakness of the monetary policy transmission in the country, see for example (Davoodi et al., 2013; Mbowe, 2015a; Montiel at al., 2012).

It is against this background that there seems a need for the Bank of Tanzania to re-assess the transmission mechanism regularly to first determine whether there is any change which could inform the Bank on how to adjust its policy actions to meet the intended results (Tahir, 2012). The understanding is expected also to enlighten the Bank on the appropriate choice of the monetary policy anchor. Lastly, the understanding of the monetary policy transmission mechanism is important for the Bank to guide on the type of financial sector/monetary reforms which are needed (Mukherjee and Bhattacharya, 2011).

Thus, this paper attempts to assess the impact of changes in monetary policy on key macroeconomic variables in Tanzania and explore the effectiveness of alternative monetary policy transmission channels.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Following the introduction section, section 2 gives an overview of the banking sector and monetary policy in Tanzania. Section 3 reviews both theoretical and empirical literature. The study’s modelling approach, the model structure and data-related issues are described in Section 4. Section 5 provides the estimation results of the empirical model. Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the main findings and providing policy recommendations as well as areas for further research.

An overview of the financial sector developments and monetary policy in Tanzania

The effectiveness and efficiency of monetary policy depend on financial sector developments which facilitate the transmission of monetary policy actions to the real economy (Montiel et al., 2012). The financial sector in Tanzania has undergone various notable developments geared towards enhancing efficiency and inclusion.

Before the 1990s, the financial sector in Tanzania was characterized by financial repression, weak and unclear institutional framework, and dominance of state-owned financial institutions which performed poorly exacerbating Non-Performing Loans (NPL) to reach 65% in 1990. Fiscal and financial operations were intermixed, and the regulatory system was characterized by inefficiencies (Cheng and Podpiera, 2008). These challenges were caused mainly by the intervention by the government in the day-to-day operation of financial institutions on pricing and resource allocations coupled with a lack of competition among financial institutions (Nyorekwa and Odhiambo, 2014). Monetary policy performance in Tanzania (1961 to 2014): A review on Banks and bank systems, (9, Iss. 4), 8 to 15. During the period, the formulation and implementation of monetary policy were guided by the Bank of Tanzania (BOT) Act, 1965 with multiple goals; to regulate the money supply, to fix monetary variables (direct controls of interest rate and exchange rate) and to provide for development finance. As a result, the Bank lacked autonomy in setting monetary policy targets. The period also exhibited underdeveloped financial markets with the absence of money and capital markets. These challenges necessitated the introduction of First-Generation Financial Sector Reforms (FGFSR) in 1991 following recommendations by the Nyirabu Commission and were followed by the Second-Generation Financial Sector Reforms (SGFSR) in 2003 following recommendations of the World Bank/IMF mission of Financial Sector Assessment Programme (FSAP) 2003.

The implementation of FGFSR allowed for the market determination of Interest rates and exchange rates; freedom of entry of the private banks (both domestic and foreign) into the banking business by enacting of BFIA 1991; enactment of Foreign Exchange Act 1992 and the Bank of Tanzania (BOT) Act 1995 (Nyagetera and Tarimo, 1997:71-77). These reforms strengthened the supervisory capacity of banks and with the BOT Act 1995, a new modality of monetary policy formulation and implementation was introduced. The Act mandated the BOT with a single objective of ensuring domestic price stability. Several indirect monetary policy instruments were introduced such as open market operations, repurchase agreements, discount and Lombard window, foreign exchange market operation as well as statutory minimum reserve requirements. The FGFSR succeeded in increasing the number of financial institutions in the market but did not succeed to make that service reach the majority of the people (financial inclusion) hence necessitate the SGFSR. The SGFSR were focused on financial inclusion, tackling the remnants of the reforms under FGFSR, including putting in place structures and institutional arrangements to support the functioning of the market economy and improve the business environment. More specifically, the SGFSR recommended, among others, continued privatization of financial institutions, removal of the main obstacles to lending, enhancement access to financial services including promotion of microfinance and creation of a credit registry.

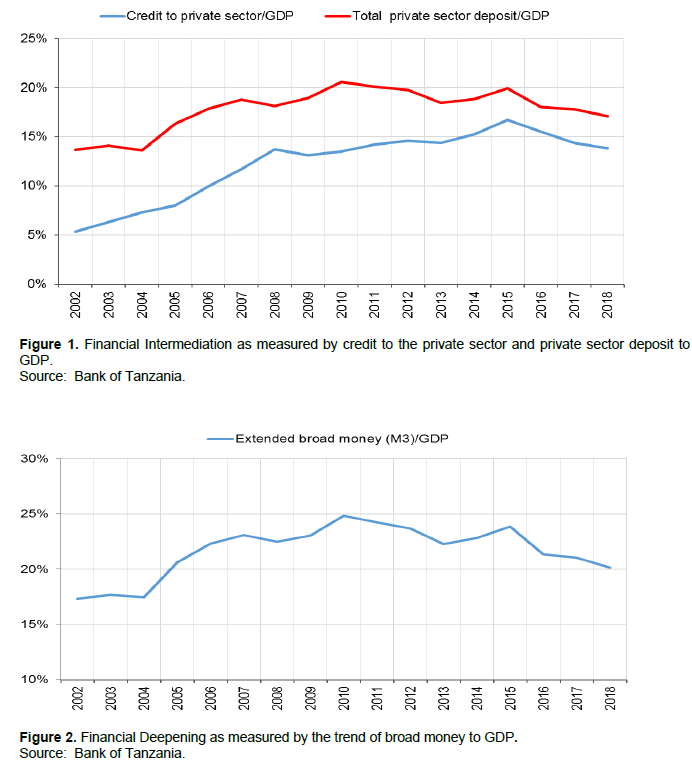

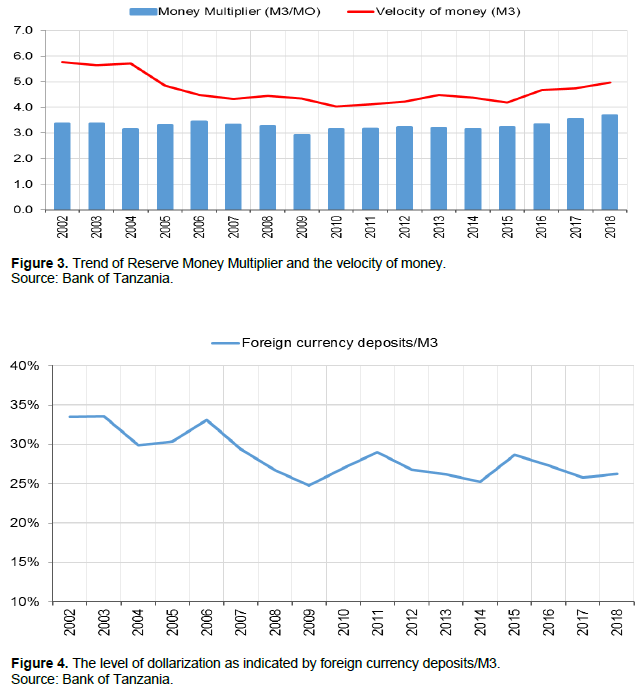

Notable financial sector developments since the onset of SGFSR include among others, the increase in the number of participants in the financial sector. For instance, the number of banks and financial institutions increased from 26 in 2004 to 58 in 2017 (BOT, Banking Supervision Report, 2004 and 2017). This reflected the increase in the financial deepening and financial intermediation as measured by the private sector credit to GDP and the ratio of bank deposits to GDP which increased to 13.7 and 17.0% in 2018 from 5.3 and 13.6% in 2002 respectively (Figure 1), Meanwhile, the level of monetization of the economy as measured by Extended Broad Money (M3) to GDP increased to 20.0% in 2018 from 14.0% in 2002 (Figure 2). The increased number of banks and financial institutions also boosted competition which is important in providing consumers with a wide range of choices on financial services.

The on-going developments in the financial sector and its products have also helped to improve financial inclusion driven mostly by the use of digital financial services and other innovative platforms, which have increased access to financial services for the majority of the population. According to the Fin Scope survey 2017 financial inclusion reached 65.05 from 11.2% in 2006 of the adult population in Tanzania.

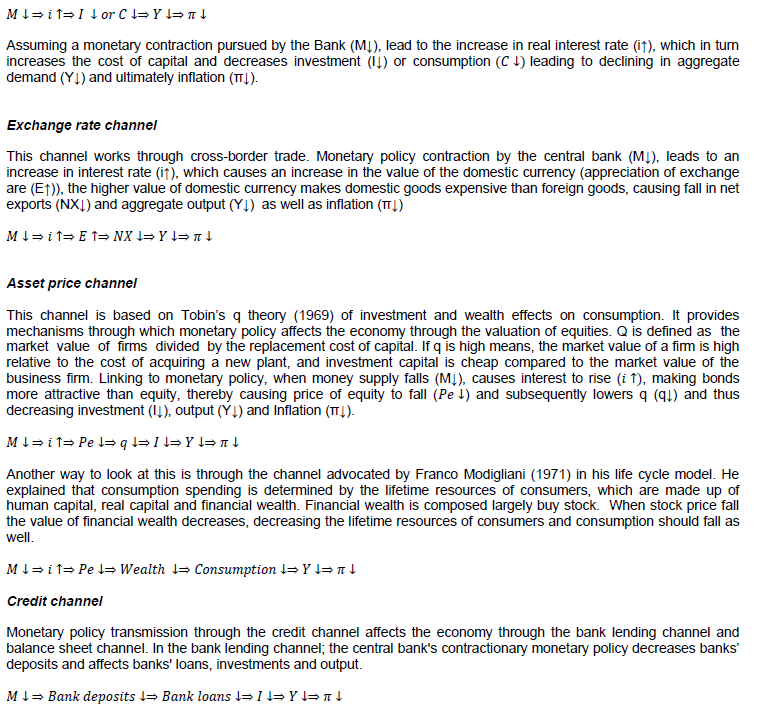

The use of innovative platforms has also impacted the velocity of money in circulation and ultimately the stability of money demand (Figure 3). This has also necessitated the Bank to rethink the appropriate channel of monetary policy transmission. It is worth noting that, financial inclusion improves the sensitivity of macroeconomic variables to the interest rate as compared to the monetary aggregate.

Over the recent years, other developments have been registered in the financial sector including the capital account liberalization initiative which was carried out in 2014 to enhance the interlinkage of the domestic financial sector with the global financial system (Kessy et al. (2017). This increased number of cross-listed companies in the equities market and instruments together with the participation in the equity market by non-residents. Meanwhile, participation in government securities by EAC residents remained minimal probably a result of the existing speed bumps.

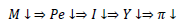

At the same time, the level of dollarization has significantly declined as indicated by the ratio of foreign currency deposits to extended broad money (M3) since a high level of dollarization indicates a lack of confidence in the local currency and hence affects negatively the effectiveness of monetary policy. In 2018, the ratio declined to 26.3% from 34.0% in 2002 (Figure 4).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Theoretical literature review

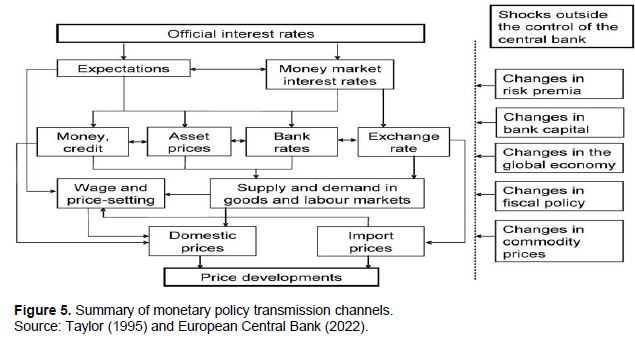

According to Taylor (1995), the monetary policy transmission mechanism can be defined as the process through which monetary policy actions impact the key macro-economic variables. As a result, monetary policy plays a crucial role in influencing economic activity and prices through several channels. The effective functioning of a particular channel depends on the properties and structure of the economy. The respective channels include; the interest rate channel, the exchange rate channel, the asset price channel and the credit channel.

Interest rate channel

The basis for an interest rate as a transmission mechanism is basic Keynesian models, which view how monetary policy is transmitted to the real economy. According to Taylor (1995), the monetary transmission mechanism lies in two key assumptions that underlie most financial market price models; rational expectations and temporary rigidities of prices and wages. For example, a rise in the nominal interest rate will cause a rise in the real interest rate if the rationally expected inflation rate does not increase by the same value. Because of the slow adjustment of goods prices, the expectation of changes in goods prices over short time horizons will also adjust slowly if expectations are rational. Hence, an increase in the nominal interest rate results in a change in the real interest rate, over the period where prices and expectations are adjusting.

On another hand, the balance sheet channel operates through the net worth of business firms as described in the asset price channel. Low net worth means borrowers have less collateral for the loans, hence a decrease in demand for loans and therefore low investment and output.

On the other hand, monetary policy, which leads to an increase in interest rate also causes a deterioration in the firm’s balance sheet by reducing cash flow. On the consumption side, contractionary monetary policy leads to a decline in equity prices, which reduces the value of financial assets, consumer spending and aggregate output.

Expectations channel

This channel works via the expectations that households and firms form about key macroeconomic variables, such as the GDP. There is an agreement amongst economists that expectations impact economic activity (Taylor, 1995). For example, expectations of depreciation in Tanzanian Shilling are likely to increase consumer prices, thus exerting inflationary pressure on overall prices. A rise in consumer prices will spur economic agents’ expectation of higher interest rates in the future to mitigate inflationary pressures, a situation which may lead to increased spending and amplified inflationary pressures in the short run. Figure 5 depicts the primary channels via which monetary policy decisions are transmitted (Taylor, 1995).

EMPIRICAL LITERATURE REVIEW

The review of the empirical literature indicates that several studies have been done in different countries with respect to the subject matter. In this study, however, the review is done for some selected studies that were done in developing countries, East African countries and Tanzania, in particular.

A review of the studies which assess the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission mechanisms agrees largely on the weakness of transmission mechanisms in developing countries (Mishra et al., 2010). The reasons cited are an underdeveloped financial system, limited international capital movements and the exchange rate regime which weakens the effectiveness of the interest rate, the asset, or the exchange rate channel. Credit channel remains the only channel presumed to work in these economies due to the dominance of the banking sector in the financial system.

However, due to underdeveloped institutions leading to high-cost financial intermediation, banks tend to hold a large percent of their deposits as reserves at the central bank and in the form of short-term foreign assets; Sacerdoti (2005). This again could weaken the transmission through the credit channel.

Buigut (2009) applied structural VAR methods to annual data from 1984 to 2005 for EAC countries. The results indicated that the effects of monetary policy on output were relatively similar for the three EAC countries in terms of the pattern and timing however, the magnitude of the impact was insignificant. In the case of inflation, the effects were different in terms of speed and direction for all countries, but the impact was also small and insignificant.

Montiel et al. (2012) using a recursive VAR model employed monthly data from Tanzania from January 2002 to September 2010 and found that reserve money had a statistically significant effect on the price level, but the effect was not economically significant. He further employed a structural VAR model and found monetary policy expansion increased lending rates and reduction in prices. He also found out that the monetary policy had negative effects on output in the first eight months and a shock. The authors attributed the counterintuitive responses of monetary policy shock to the weak monetary policy transmission in Tanzania.

Davoodi et al. (2013) used a recursive VAR model and estimated for 2000 to 2010, to study the monetary transmission mechanism in the East African Countries and concluded that the precise transmission channels and their importance differ across EAC. For Tanzania, the authors found out that, the positive shock to reserve money increases inflation in the first year and a half though the effect was not statistically significant. However, when he applied VAR for a longer period, the results were highly significant. Similar conclusions were obtained using BVAR and FAVAR. Also using similar sample periods, they found out that a positive shock to the interest rate increases inflation, a “price puzzle” however the impact was not statistically significant which indicates weak monetary transmission. The authors argue that a weak monetary transmission mechanism can be a result of an unstable money multiplier and velocity in the short run. The authors conclude that shocks to reserve money are transmitted to money, but transmission from money to prices or output is weak because shifts in velocity, caused perhaps by financial innovations, may attenuate any aggregate demand effects. The other reason for the weak monetary transmission mechanism in Tanzania was cited as the presence of capital controls, especially on the exchange rate channel.

Mbowe (2015a) investigated the pass-through of the monetary policy rate to banks' retail rates in Tanzania using an error correction model. The study aimed at providing insight into the pass-through of the monetary policy rate to the interbank rate and retail bank interest rates in Tanzania. The study concluded that the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission to the economy through the interest rate channel may be limited due to weak and lagged pass-through of the interbank rate to deposit rate, though the pass through of the policy rate to interbank rate was generally strong.

A similar observation was noted by Berg et al. (2013) by using a narrative approach. The study also found that, the exchange rate was responding to the tightening monetary policy episodes, which is different from the findings from empirical studies by Montiel et al. (2012) and Davoodi et al. (2013) who found that this channel is weak due to controls imposed in the cross-border movement of capital. In the same vein, Balele et al. (2018) obtained a similar observation, where monetary policy seems to have a weak influence on core inflation.

On the other hand, the bank lending channel was noted to be strong in Tanzania, Mbowe (2015b); and Berg et al. (2013). However, Mbowe cautioned that the reaction by banks was asymmetric based on ownership structure, whereby lending channel was stronger through domestically-owned banks and privately-owned banks than foreign-owned banks and public-owned banks, possibly due to having other sources of funding.

METHODOLOGY

Model specification

The Vector Autoregression (VAR) model pioneered by (Sims, 1980) has been extensively used when assessing the monetary policy transmission mechanism. Structural VAR is an extension of VAR, which intends to remove the drawbacks in the VAR methodology, see for example (Pham, 2016).

In SVAR, there are several assumptions (grounded on economic theory) that have to be made with regard to the relationship among macroeconomic variables before estimation. Therefore, the SVAR approach helps to give several inferences for the model parameter and also describes the nature of the shock as whether transitory or permanent, see for example (Nguyen, 2014) and (Pham, 2016). The current study employs structural VAR to assess the monetary policy transmission mechanism in Tanzania. The Structural VAR takes the following general representation:

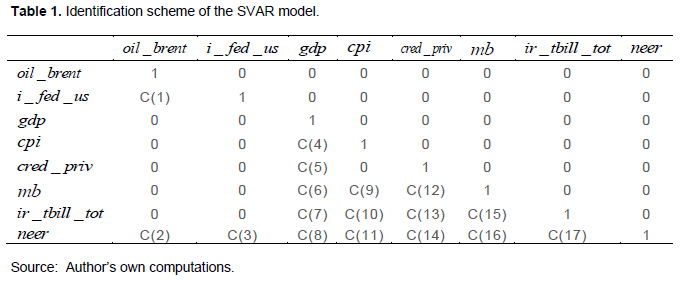

Identification of the SVAR Model

The fundamental concern in the estimation of the structural VAR model is the identification of the empirical model. The identification of monetary policy shocks requires adequate short-run restrictions on the SVAR model, Bernanke (1986) and Sims (1992). As a result, there is a need that equation (3) to be restricted with parameters that are theory-consistent. The canonical SVAR model is represented as follows:

The first identification is about foreign variables whereby we assume that the international oil prices are completely exogenous in the sense that they are contemporaneously affected by factors outside the specified model. In the second identification, US monetary policy (Fed’s fund rate) is assumed to react contemporaneously to changes in international oil prices.

The exchange rate (the most endogenous variable in the model) is assumed to be contemporaneously affected by all variables in the model. Prices and supply of credit to the private sector are assumed to be instantaneously driven by output and in the case of money demand behaviour. The money equation (M), represented as real money balance, follows the traditional money demand that is contemporaneously influenced by the level of output (GDP), and prices (CPI).

And lastly, interest on treasury bills is assumed to be driven by GDP, prices and shock to monetary aggregates both credit and the monetary base.

Data and variables

The study uses quarterly data covering the first quarter of 2002 to the fourth quarter of 2018. As in many VAR studies, the analysis is done in the first difference of the variables which are seasonally adjusted. All the variables are expressed in logarithms.

Before the estimation of the model, the time-series properties of each of the variables in the model was examined, two widely-used unit root tests were performed: the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test and the Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, and Shin (KPSS) test. The overall results suggest that most variables under consideration have a unit root in a level form but are stationary in the first-order log-difference form.

Having specified the model, the appropriate lag length of the VAR model was decided using the Akaike information criteria (AIC). There is an advantage of selecting optimal lag length since choosing a relatively too large lag length will typically result in poor and inefficient estimates of the parameters while a too-short lag length, will lead to biased estimates, as unexplained information will be left in the error term. The adjustment was made to allow for more lags to ensure the residuals are white noise.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Unit root test for model variables

Results of the ADF and PP unit root tests are reported in Annex 2. Except for credit to the private sector and reserve money, all other variables have unit root in level. However, after differencing, the null hypothesis of unit root is rejected for all variables at all significance levels implying all variables are I (1) (Annex 1).

Selection of lag length

The results of lag length based on various lag selection criteria are provided in Annex 3. The results indicate that Schwarz information criterion (SC) and Hannan-Quinn information criterion (HQ) supported a lag length of 1 while sequentially modified LR test statistic and Final prediction error (FPE) proposed a lag length of 2. On the other hand, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) recommended a lag length of 5. The study picks a lag length of 2 in the baseline model and a lag length of 3 in the robustness check.

Model estimation results

Contemporaneous coefficients

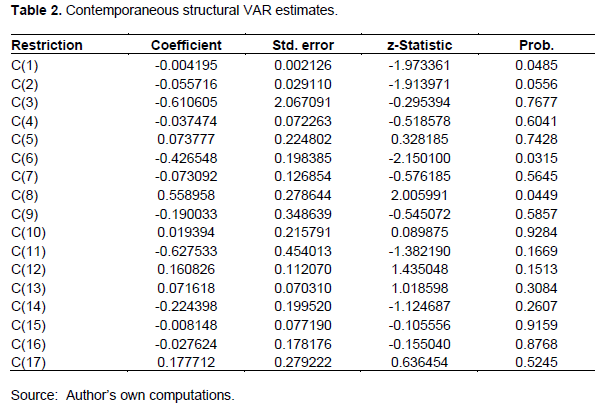

Table 2 presents the coefficients of the SVAR identification restrictions that were estimated using the OLS method. The results indicate that 4 out of 17 estimated structural contemporaneous parameters are statistically significant. The majority of the parameters appear to be statistically insignificant meaning that there exists no meaningful instantaneous relationship between the variables in the SVAR model (Annex 4).

The first significant parameter is C (1) which captures the contemporaneous effect of the changes in international oil prices on the US fed fund rate. The coefficient carries a negative sign, implying that the Fed fund rate reacts negatively to the rising global oil prices.

The second parameter is C (2) which captures the contemporaneous pass-through of the international oil prices to the nominal exchange rate of the Tanzanian Shilling against a basket of currencies. Again, the coefficient carries a negative sign, which means that an increase in global oil prices leads to an appreciation of the currency; this is counter-intuitive since Tanzania is not an oil-exporting country.

The third coefficient is C (6) which captures the instantaneous reaction of monetary policy (through the monetary base) to aggregate demand shock (output). The coefficient is negative implying that, the monetary policy responds negatively to a positive demand shock (increase in output). This is counter-intuitive based on the quantity theory of money (Friedman and Schwarts, 1963).

The last coefficient is C (8) which captures the contemporaneous reaction of the exchange rate to an aggregate demand shock. The coefficient is positive implying that, an increase in output causes depreciation of the nominal exchange rate.

The nature of causality between macroeconomic variables present in the model was also assessed by using the Granger causality test as reported in Annex 5.

Although the SVAR is a very reliable method in econometric analysis, it is challenging to interpret the coefficients of the contemporaneous relationships straight. As a result, Stock and Watson (2001) suggested the impulse response functions and forecast error variance decomposition as more powerful explanatory techniques to understand the relationship among the variables.

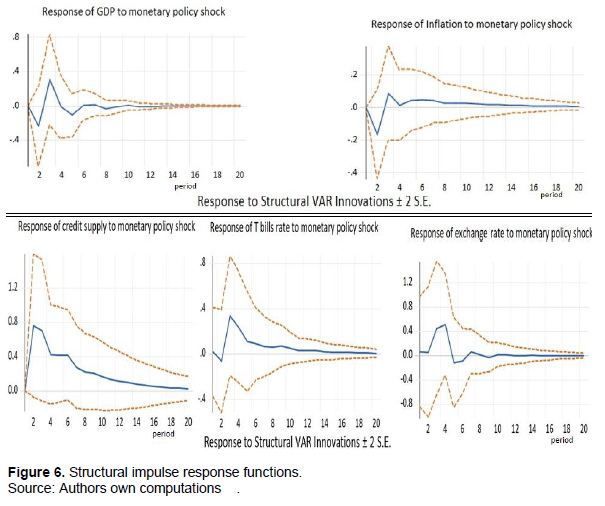

Structural impulse response function

Figure 6 reports the results of the structural impulse response functions for all variables in the SVAR model. The impulse response functions show the dynamic response of output, prices, exchange rate, credit to the private sector and nominal exchange rate to a positive monetary policy shock (increase in reserve money) over 20 quarters. The reserve money is chosen as a proxy for monetary policy shocks since it is regarded as a de facto operating target in the monetary policy formulation and implementation by the Bank of Tanzania. Point estimates (the solid line) and the 90% confidence intervals (the dashed lines) are graphed for all the variables (Annex 6).

i) Initially, the monetary policy easing lowers output marginally in the first two quarters, which is inconsistent with the economic theory before starting to increase in the succeeding quarters. The maximum impact of the monetary policy shock is attained after three quarters. This finding is consistent with the study by Montiel et al. (2012) and perhaps indicates the dominance of supply factors in explaining output variation in Tanzania.

ii) Similarly, as a result of the initial decline in output, prices fall slightly in the first two quarters consistent with economic theory. Thereafter, prices start to increase. The peak effect of monetary policy shock on prices is attained after four quarters. This finding is also consistent with the study by Montiel et al. (2012).

iii) Following monetary policy easing, the supply of credit to the private sector responds positively peaking in the second quarter and remaining positive throughout the period. This signals the effectiveness of the credit/bank lending channel in line with the findings of the study by Mbowe (2015b).

iv) As expected, following the monetary policy shock, the treasury bills rate responds negatively in the first two quarters before starting to increase in successive quarters.

v) As a result of monetary policy easing, the exchange rate depreciates and remains so for about five quarters consistent with economic theory.

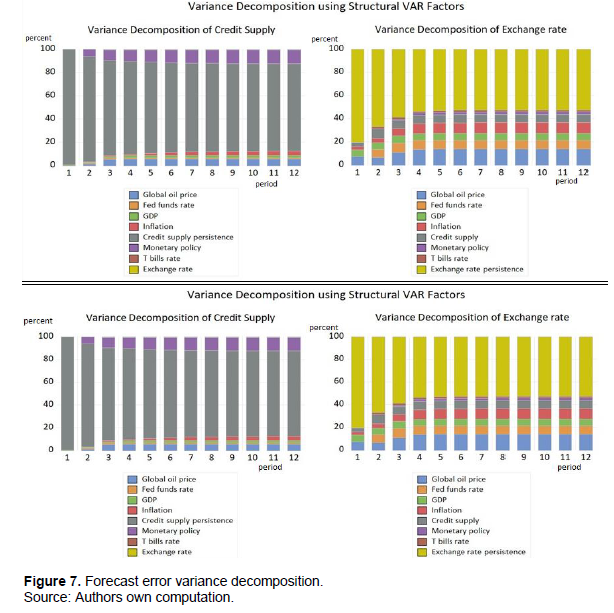

Forecast error variance decomposition

The results of forecast error variance decompositions for GDP, Inflation, the supply of credit to the private sector and nominal effective exchange rate are illustrated in Figure 7 and Annexes 7 and 10. The variance decompositions are computed using the Monte Carlo approach of Runkle (1987). The forecast error variance decomposition splits the variation in an endogenous variable into the component shocks to the SVAR. Therefore, the variance decomposition gives information about the comparative importance of each shock in affecting the variables in the SVAR model.

The results of the variance decomposition of the SVAR model show that the variation in output is mostly by itself. The fluctuations due to reserve money are not so large indicating that the transmission of the monetary shocks into the real economy is rather weak (Twinoburyo and Odhiambo (2018). Innovations in the monetary policy account for almost 3.7% of fluctuations in GDP after 4 quarters and 4.0% after 8 quarters (Annex 10). The GDP dynamics is mainly explained by changes in the global oil prices and changes in the nominal exchange rate that account for 4.7 and 4.0% respectively in variation in output after four quarters. The high contribution of international oil prices on output may be explained by the fact that changes in global oil prices impact production costs domestically.

About 77.1% of inflation dynamics after four quarters are mostly due to its innovations, indicating a relatively high degree of inflation persistence. After four quarters, inflation dynamics are mainly explained by variations in global oil prices (8.2%) and domestic demand conditions (5.5%) while monetary policy explains only 2.3%. The results imply that the role of monetary policy in explaining GDP dynamics is relatively much stronger compared to inflation dynamics.

Thus, the forecast error variance decomposition results with regard to the effectiveness of monetary policy in explaining the ultimate policy variables indicate that the transmission is weak. On the other hand, results indicate that the money supply is relatively stronger in explaining variation in output compared to inflation dynamics.

The results also indicate that the contribution of monetary policy in the variation of the supply of credit to the private sector is the largest among all variables in the model. It contributes about 10% after four quarters.

It can also be noted from the results of the forecast error variance decomposition that the significance of the variables' own innovations may imply the importance of structural factors such as exogenous supply shocks, terms of trade and productivity shocks and expectations in explaining the dynamics of the model variables.

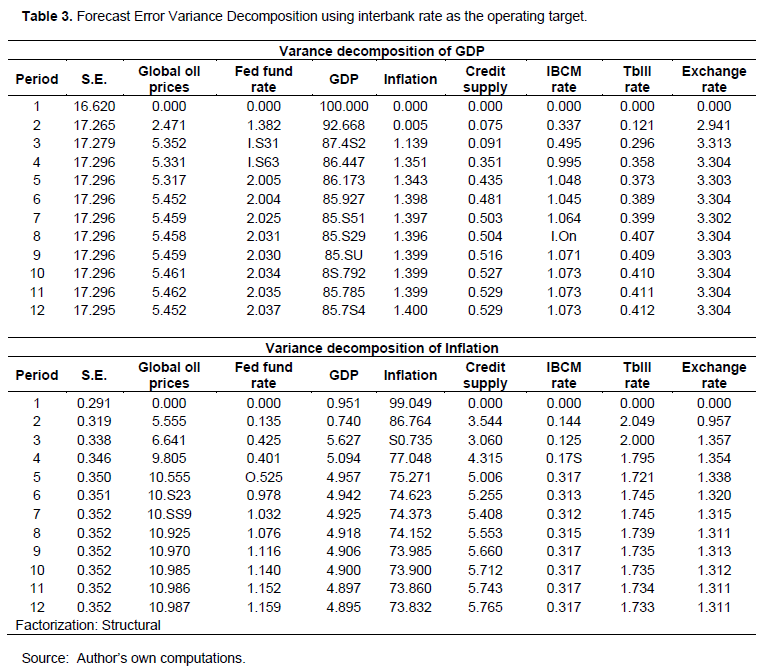

Variance decomposition using interbank rate as an operating target

Figure 7 shows the forecast error variance decomposition using the interbank rate as a monetary policy operating target. The results indicate that the interbank bank rate is relatively weaker in explaining output and inflation variations than the monetary base. The weakness of the interest rate can be attributed to the fact that; the monetary base has been used as a monetary policy operating target while the interest rate was taken exogenously. Table 3 show the forecast error variance decomposition using interbank rate as the operating target.

Robustness checks

For robustness purposes, two approaches are used. In the first approach, the results of forecast error variance decomposition using structural identification are compared with Cholesky identification using the same number of lags. The results are broadly identical confirming thatthe structural identification was robust in identifying responses to the monetary policy shock (Annex 8). In the second approach, the results of the forecast error variance decomposition using structural identification with two lags are compared with forecast error variance decomposition using structural identification with one lag (Annexes 9 and 10). Likewise, the results are broadly the same, confirming that the baseline specification of the model was appropriate.

Comparison with other studies

The results of the study are broadly similar to those of Montiel et al. (2012), Mbowe (2015a) and Berg et al. (2013) on the weaker role of monetary policy for macroeconomic stabilization. Also, the strength of the bank lending channel is similar to the findings by Mbowe (2015b).

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATION

This study endeavoured to assess the monetary policy transmission mechanism in Tanzania over the period 2002 to 2018. The study used the average reserve money as a measure of the stance of the monetary policy.

Generally, consistent with other studies in developing countries; the empirical findings indicate that the effectiveness of monetary policy in explaining GDP and inflation variations is relatively weak. This implies that the responsiveness of output and prices to changes in monetary policy are generally limited and slow.

Nevertheless, it appears that the impact of monetary policy in Tanzania is relatively stronger in explaining the dynamics of credit supply and output than in the case of inflation. Inflation dynamics are highly influenced by developments in international oil prices. The global oil prices also explain much of the variations in the nominal exchange rate.

The result portrays two major policy implications, the first one being sustaining financial sector reforms geared towards eliminating the remaining structural impediments that hinder financial deepening.

Secondly, to enhance price stabilization, the Bank may opt to switch to an alternative monetary policy framework. The alternative framework could be inflation targeting using interest as an operating target. The inflation-targeting framework has proved to be successful in other countries and is also set to be the de facto framework under the envisaged East African Monetary Union (EAMU) in 2024.

Regarding the weak transmission of monetary policy to prices, the study recommends the Bank of Tanzania embark on an inflation-targeting framework using the interest rate as an operating target to enhance price stabilization.

Also, the Bank of Tanzania should continue monitoring global developments, especially the movements in international oil prices to constrain the impact of the shocks and safeguard domestic macroeconomic stability.

Concerning areas for further research, the study might benefit from further research in the following lines of enquiry.

The first inquiry should base on an investigation of the relative importance of fiscal policy in driving price and output dynamics. This might be achieved by the inclusion of the overall deficit to GDP ratio in the model to capture the stance of the fiscal policy.

Another interesting area for further research is to analyse whether the weak effects of monetary policy on key macroeconomic variables are present also in other East African countries.

Lastly, it is also recommended to do another study that will split the sample between two periods, that is, the period before and after financial innovations which started in 2013/14 to gauge the relative strength of the monetary policy in the two episodes. This was not done in the current study due to data limitations, particularly after the financial innovations.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Balele N, Kessy N, Mpemba Z, Aminiel F, Sije G, Mung'ong'o E (2018). Financial Sector Reforms and Innovations and their Implications on Monetary Policy Transmission in Tanzania, Bank of Tanzania working paper, Dar es salaam. |

|

|

Bank of Tanzania (BOT) (1965). Bank of Tanzania Act. Dar es salaam. Tanzania. |

|

|

Bank of Tanzania (BOT) (1995). Bank of Tanzania Act. Dar es salaam. Tanzania. |

|

|

Bank of Tanzania (BOT) (2004). Banking Supervision Report. Dar es salaam. Tanzania. |

|

|

Bank of Tanzania (BOT) (2006). Bank of Tanzania Act. Dar es salaam. Tanzania. |

|

|

Bank of Tanzania (BOT) (2017). Banking Supervision Report. Dar es salaam. Tanzania. |

|

|

Bank of Tanzania (BOT) (2018). Monetary Policy Statement 2018/19. Dar es salaam. Tanzania. |

|

|

BFIA (1991). Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1991, Cap 342 (the "BFIA '91"). |

|

|

Berg MA, Charry ML, Portillo MRA, Vlcek MJ (2013). The monetary transmission mechanism in the tropics: A narrative approach. International Monetary Fund. |

|

|

Bernanke BS (1986). Alternative explanations of the money-income correlation, Econometric Research Memorandum No. 321. |

|

|

Buigut S (2009). Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanism: Implications for the Proposed East African Community (EAC) Monetary Union, available at: |

|

|

Carranza L, Galdon-Sanchez JE, Gomez-Biscarri J (2010). Understanding the relationship between financial development and monetary policy. Review of International Economics 18(5):849-864. |

|

|

Cheng K, Podpiera R (2008). Promoting Private Sector Credit in the East African Community: Issues Challenges and Reform Strategies. Washington DC: World Bank. |

|

|

Davoodi HR, Dixit S, Pinter G (2013). Monetary Transmission Mechanism in the East African Community: An Empirical Investigation, IMF Working Paper 13/39. |

|

|

Friedman M, Schwarts AJ (1963). Money and Business Cycles. Review of Economics and Statistics. |

|

|

FinScope Survey (2017). 'Insights That Drive Financial Inclusion'. Dar es Salaam: FinScope Tanzania. Available at: |

|

|

FSAP (2003). The 2003 Tanzania FSAP report is available online at: |

|

|

FSDT (2017). State of The Financial Sector: are Financial Services Meeting the Needs of the Market? Supply-Side Report. |

|

|

Kessy PJ, Nyella J, Stephen AC (2017). Monetary Policy in Tanzania. Africa: Policies for Prosperity Series P 241. |

|

|

Ma Y, Lin X (2016). Financial development and the effectiveness of monetary policy. Journal of Banking and Finance 68:1-11. |

|

|

Mbowe WEN (2015a). Monetary Policy Rate Pass-through to Retail Bank Interest Rates in Tanzania. Bank of Tanzania working papers. |

|

|

Mbowe WEN (2015b). The Bank Lending Channel of Monetary Policy Transmission: Estimation using Bank-Level Panel Data on Tanzania, Bank of Tanzania working papers. |

|

|

Mishkin F (1995). Symposium on the Monetary Transmission Mechanism: Journal of Economic Perspectives 9(4). |

|

|

Mishkin F (1996). The Channels of Monetary Transmission: Lessons for Monetary Policy, NBER Working Paper no. 5464. |

|

|

Mishra MP, Montiel MP, Spilimbergo MA (2010). Monetary Transmission in Low Income Countries, IMF Working Paper. |

|

|

Mishra P, Montiel PJ, Spilimbergo A (2012). Monetary transmission in low-income countries: effectiveness and policy implications. IMF Economic Review 60(2):270-302. |

|

|

Modigliani F (1971). Consumer Spending and Monetary Policy: The Linkages. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Conference Series 5. |

|

|

Montiel P, Adam CS, Mbowe W, O'Connell S (2012). Financial Architecture and the Monetary Transmission Mechanism in Tanzania, CSAE Working Paper, WPS/2012-03. |

|

|

Mukherjee S, Bhattacharya R (2011). Inflation Targeting and Transmission Mechanisms in Emerging Economies, IMF working Paper no. 11/229. |

|

|

Nyagetera BM, Tarimo B (1997). 'Financial and Monetary Sector Management During and After Reform in Tanzania'. In D. Bol, et al., (eds.). Economic Management in Tanzania, Dar es Salaam, Economic Research Bureau and Department of Economics. |

|

|

Nguyen HT (2014). Monetary transmission mechanism analysis in a small, open economy: The case of Vietnam. PhD thesis, University of Wollongong. |

|

|

Nyorekwa E, Odhiambo N (2014). Monetary policy performance in Tanzania (1961-2014): A review. Banks and Bank Systems 9(4):8-15. |

|

|

Pham TA (2016). Monetary policies and the macroeconomic performance of Vietnam. PhD Thesis. Queensland University of Technology. Available from: |

|

|

Runkle DE (1987). Vector Autoregressions and Reality, Journal of Business and Economic Statistics pp. 437-442. |

|

|

Sacerdoti E (2005). Access to bank credit in Sub Saharan Africa: Key Issues and Reform Strategies. Washington DC: IMF. |

|

|

Sims CA (1980). Macroeconomics and Reality, Econometrica 48:1-49. |

|

|

Sims CA (1992). Interpreting the macroeconomic time series facts: The effects of monetary policy. European Economic Review 36:975-1000. |

|

|

Stock JH, Watson MW (2001). Vector Auto regressions. Journal of Economic Perspectives 15:101-115. |

|

|

Tahir MN (2012). Relative Importance of Monetary Transmission Channels: A Structural Investigation; A case of Brazil, Chile, and Korea. University of Lyon Working Paper Series. |

|

|

Taylor JB (1995). The Monetary Transmission Mechanism: An Empirical Framework. Journal of Economic Perspectives 9(4):11-26. |

|

|

Tobin J (1969). A General Equilibrium Approach to Monetary Theory. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 1(1):15-29. |

|

|

Twinoburyo EN, Odhiambo NM (2018). Can Monetary Policy drive economic growth? Empirical evidence from Tanzania. Contemporary Economics 12(2):207-222. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0