ABSTRACT

Globalization as a concept surpasses a mere openness to symbiotic economic relationship. Globalization refers to the level of openness and positive attitude towards the products, values and ideologies of other people and cultures. The study reviews existing literature on the impact of globalization on work ethics across the globe and tries to observe possible trends of convergence of work ethics among several countries. Most of the reviewed studies revealed a significant impact of globalization on work ethics. The more recent studies also showed trends of convergence among some countries that are geographically far apart and initially had different cultural orientations to work. Since globalization is a continuous process, the degree of this convergence may vary as time goes on.

Key words: Globalization, global openness, capitalist work ethics, Islamic work ethics, socialist work ethics.

The concept of work ethics has been used as a broad term to describe the set of moral principles a person abides by in the course of fulfilling their task (Alam and Talib, 2015). The work ethics in a particular environment is closely linked with the cultural ideology and religion being practiced in such a place (Baguma and Furnham, 1993). For this reason, work ethics can be influenced by the degree of openness to foreign cultures and ideologies that are made possible through globalization. Globalization is a term that is commonly used in recent times to refer to the suppression of barriers to economic trade and openness to foreign economic interest. However, in this study, we view globalization for the perspective of the general direction in which the world as a whole is moving towards (Velho, 1997). Globalization refers to the influence (whether economic, social or political) that countries and regions have over one another through the inter-transfer of people, products and values. Globalization, in this light, can be seen as providing a medium for exchange of work ethics in terms of attitude to work.

Several studies have investigated the possible impact of globalization on the work ethics of individuals living in a particular community and have offered different (sometimes conflicting) results. Thus, there is need to review these studies and bring together the different results. Also, globalization is a two-way street because all the parties involved get to influence and be influenced by others. Thus, if globalization has indeed influenced work ethics, there ought to be some traces of convergence of work ethics among the countries that were studied. This study tries to fill these gaps by reviewing recent empirical works that associate globalization with work ethics. This study tries to bring together most of these previous empirical works and compare their results to identify traces of convergence of work ethics among the different countries that were studied.

The next four sections of this paper present a conceptual review of globalization and work ethics, a review of theories that explain the expected impact of globalization on work ethics and a systematic review of empirical literature on impact of globalization on work ethics. The results were examined and discussed in the discussion session. The remainder of the paper consists of conclusion, limitations, implications and future research directions.

Conceptual review

The concept of globalization is one that has attained common usage in recent times and has been used as a general term to describe global openness to foreign trade relationships. However, some authors have tried to give varying views on the concept of globalization that transcend the solely economic perspective and in accord with existing theories (Robertson, 2007; Robertson and Lechner, 1985; Suh and Kwon, 2002; Schütte and Ciarlante, 1998). Work ethics is a term that has also evolved over time and across several regions. Different perspectives to work ethics have been reviewed in existing literature and will be discussed in later sections.

Globalization

The dynamic theory of globalization recognizes different levels of globalization in the mindset of individuals, businesses and countries (Suh and Smith, 2008). These levels of globalization differ in terms dimensions. For instance, there is a psychological dimension and an economic dimension to globalization and a country can progress in one while remaining the same in the other (Schütte and Ciarlante, 1998; Suh and Kwon, 2002).

Establishment of institutions and increase in global economic activity may increase a country’s level of economic globalization but may not have any real effect on their level of cultural or psychological development if there is no openness and positive attitude towards cultural or psychological globalization. There are several other definitions that address globalization in this light.

Robertson and Lechner (1985) define globalization as the processes through which the world is being made into a single place with systemic properties. The popular notion of the world being a ‘global village’ has its roots in this definition. Meanwhile, Schütte and Ciarlante (1998) define globalization as a psychological and spiritual process of deepening consciousness and increasing sensitivity to the culture and values of other people. Suh and Kwon (2002) tried to define globalization with its constituent effect. They describe it as the long-term effort to integrate the global dimensions of life into each country’s economic, political, and cultural systems. The economic globalization is often the first step of globalization, which is then followed by the others (political and cultural). According to Robertson (2007), globalization refers to the transmission of ideas and intermingling of culture across borders.

In this study, we view globalization in aggregate terms as the general direction in which the world as a whole is moving towards (Velho, 1997). Globalization refers to the influence (whether economic, social or political) that countries and regions have over one another through the inter-transfer of people, products and values. This takes the form of a symbiotic or complementary relationship and ought to lead to a convergence of values across the participants. Globalization, in this light, can be seen as providing a medium for exchange of work ethics in terms of attitude to work.

Work ethics

From an individual perspective, work ethics can be described as a set of moral principles a person abides by in the course of fulfilling their task. From an organizational perspective, work ethics refers to the professional or business codes of conduct that sets the standard for judging the values and moral actions of employers and employees that arise in the course of the business (Alam and Talib, 2015). Different approaches to work ethics have eloped over time but these different approaches have been summarized to two broad perspectives; the Capitalist perspective and the anti-capitalist perspective.

Capitalist perspective of work ethics

The capitalist work ethics originated from the protestant work ethics by Max Weber and can be traced back to the seventeenth and eighteenth century (Weber, 1930). The protestant work ethics summarizes the puritan attitude towards work that characterized the early Protestants (Calvinists) who saw working hard as a sign of predestination. Phrases like ‘time is money’ and ‘he who does not work, let him not eat’ were commonly used in this era. Some major defining characteristics of the protestant work ethics are; belief in hard work, leisure avoidance, independence from others, and asceticism (Furnham, 1990). According to Scherer et al. (2009), the protestant work ethics became linked with capitalism in the nineteenth century, which was characterized by a period of brutal capitalism. This era saw many capitalist entrepreneurs (e.g. Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew Carnegie, J.D Rockefeller, J.P Morgan) who saw worldly success as a sign of divine grace. Thus, they felt the need to make even more money and give back to society. The common notion of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as ‘mere philanthropy’ has its root in this era. The capitalist work ethics is more individualistic and values work with respect to productivity and profit. It was hinged on a general belief of egalitarianism (referring more to all men deserving equal opportunity than having equal human dignity), and thus reward systems for work was based on individual merit (Mirels and Garrett, 1971). The work ethics of Western countries have been commonly found to portray the features of capitalist/protestant work ethics. Some of the negative consequences of the extreme version of this work ethics include workaholism, suppression of humor and objectification of labor force (which goes against the fundamental principle of egalitarianism).

Anti-capitalist perspective of work ethics

Some of the foundational principles behind the anti-capitalist perspective to work ethics can be traced to the socialism of Karl Max. However, the anti-capitalist work ethics was majorly championed by André Gorz, a French philosopher. He argued that the need for higher levels of production have already been met (there is enough resource to go round) and that increase in production did not result in increase in quality of life before the era of capitalism and even afterwards (Gorz, 2001). He refuted the capitalist pitch of hard work as an agenda to get the poor to work and increase the wealth of the rich. To protect the interest of the community rather than individual interest, he discourages competition among paid labor workers and suggested that people should work less so as to give others an opportunity to work and earn a living. Unlike the capitalist perspective, this perspective peculiarly supports collectivism (Heins, 1993).

Although the Islamic work ethics, which was first introduce by Ali (1988), shares some characteristics with the protestant work ethics (belief in hard work, careful use of time, asceticism), but it emphasizes more collectivism (collaboration at work and consideration for our fellow men) as opposed to individualism. Elements of collectivism can be observed from the no-interest policy on lending, prohibition of gambling and prohibition of risk sharing (Shirokanova, 2015). The Islamic work ethic hinges more on religion compared to the protestant work ethics as it promotes hard work as long as it does not go against the dictates of the Islam religion (Ahmad and Owoyemi, 2012).

Globalization and work ethics

With the growing levels of migration, foreign economic interest and trade relationships among governments and multinationals, countries are being affected whether voluntarily or involuntarily by the value systems of other countries. Even though the effects of globalization often begin with economic relationships, globalization should not be seen merely as a means to acquire economic prowess but should transcend to openness towards the positive aspects of other cultures (Pope Francis, 2020). No cultural, economic or political system is complete (each society holds a piece of the whole) and only through intermingling of cultures do we benefit from the positive aspects of other cultures.

Globalization has influenced the diffusion of cultural values across countries and continents and these values have a major influence on the work ethics of that environment (Baguma and Furnham, 1993; Ladhari et al., 2015). On this basis, it could be inferred that the current trend of globalization ought to influence the work ethics in different countries through their cultural values as can be seen in the conceptual model (Figure 1). The convergence of cultural values that has been observed in recent years ought to be accompanied by a convergence of work ethics across the globe.

Theoretical review

There are several theories that relate to globalization as well as to work ethics. However, only a few of these theories explain the nature of the relationship between globalization and work ethics. One of these theories is the conventional theory of globalization. The conventional theory suggests that globalization has an impact on the willingness of a particular country to adopt ideas, values and products of other countries.

Conventional theory of globalization

The conventional theory originated as a theory on Country of origin effects (Nagashima, 1970) but has been used as a general theory to explain the attitude of individuals and countries towards globalization (Roth and Romeo, 1992; Suh and Smith, 2008). The conventional theory suggests that individuals, businesses and countries are reluctant to change, and thus tend to reject foreign ideas, values and products. This preference for the status quo may be fueled by a lack of trust in foreign ideas and products (country of origin effect) or an irrational preference for products and ideas of local origin (ethnocentrism). Regarding work ethics, the theory suggests an absence of relationship between globalization and work ethics since countries would prefer to stick to their own values and attitude to work than adopt foreign values. Given that the conventional theory of globalization was the most relevant theory for this study, we use it as our main model for contextualizing the results of the reviewed studies.

The research questions of this study were investigated using the systematic review method. This method can be considered appropriate as it involves a review of existing literature on globalization and work ethics with the aim of extracting and mapping the different research findings as well as detection of patterns that could answer some pertinent questions or suggest areas for further research (O'Gorman et al., 2013).

Article search and selection strategy

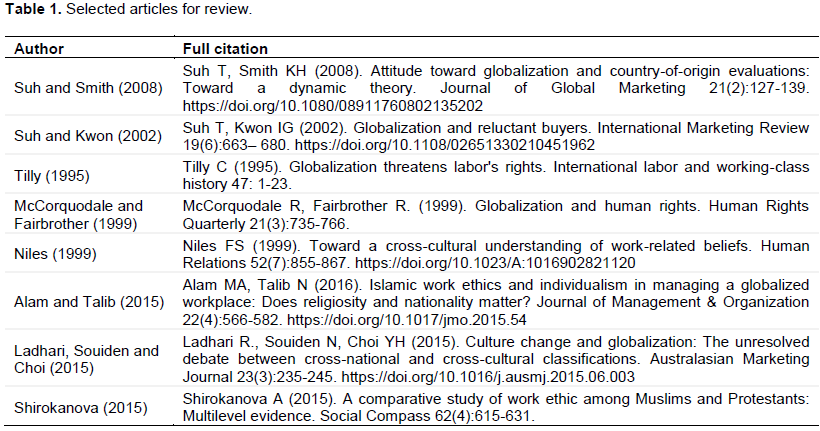

Studies that have investigated the impact of globalization on work ethics directly are quite scanty. Most of the studies investigate the impact of globalization on work ethics in the light of cultural bias (like ethnocentrisms and country-of-origin bias) and enforcement of labor laws. Thus, studies that discuss globalization in this light were selected for review. Since the flourishing of globalization in the 1990’s, the ethical conduct of multinational companies and other companies whose activities occur across borders have gained special interest (Tian et al., 2015). The reason for this can be traced to the fact that some authors have identified work ethics as one of those resources that can give an organization competitive advantage (Manroop et al., 2014). For this reason, this study targeted empirical studies that have been carried out from 1995 to 2015. Only works that were done within this time frame, addressed the structural research question (what is the nature of the impact of globalization on work ethics?), were empirical in nature (or at least involved some rigorous methodology), and approached the study in the light of cultural bias and enforcement of labor rights were selected. Only eight (8) works met these criteria (Table 1) and thus were reviewed extensively and mapped according to their findings.

Impact of globalization on work ethics

Several works have attempted to evaluate the effect of globalization on the adoption of different approaches to work ethics in different countries. The elements that make up the different work ethics in a particular country can be partly traced to some cultural ideas which may be of domestic or foreign origin. Few authors are of the opinion that globalization has not really changed the approach to culture and work ethics in some countries. For instance, Suh and Smith (2008), in their study, tried to test the impact of globalization on the decision to accept or reject certain ideas or products of foreign origin. They carried out a study on the attitude of individuals towards globalization (global openness) and Country-of-Origin effect. Country of origin effect was measured from a positive perspective (i.e. the tendency to accept a product or idea due to its country of origin). They tested data from a sample of 133 residents in Korea. They discovered that there is a negative relationship between individual ethnocentrism and country of origin effect while there was no relationship between globalization and country of origin effect. Thus, globalization has not had any significant effect on the reduction of country of origin bias.

These results are similar to those of Suh and Kwon (2002). Suh and Kwon (2002) did a study on ‘globalization and reluctant buyers’ in which they tried to test the hypothesis that globalization has led to homogeneity in consumers’ buying behavior (in terms of reluctance to purchase foreign-made goods). Using samples of US and Korea, they found that customers are more reluctant to purchase foreign-made goods, in spite of the increasing level of global openness. The reason was attributed to consumer ethnocentrism (in both countries) and product judgment (in US only). They also discovered that, despite the growing trend of globalization, countries with different buying culture have remained different, thus emphasizing a lack of impact on the part of globalization and confirming the conventional theory of globalization. These studies may have only addressed buying behavior for products but the reasons for the lack of influence of globalization can be attributed to cultural ideas and work ethics as well.

Some other authors like Tilly (1995) have even advocated that globalization has a negative effect on work ethics. The author argues that the ability of the state to protect the rights of workers (and indeed, enforce other social policies) is highly dependent on their ability to control the stocks and flows of migration, drugs, capital, technology, political practices and other culture carriers. Given the fact that globalization has reduced the control of the state over these factors, the power and ability of the state to enforce and protect worker’s rights is reduced.

On the other hand, several authors have found globalization to have a positive influence on the diffusion of certain aspects of culture and work ethics across the globe. McCorquodale and Fairbrother (1999) tried to examine the impact of globalization on human rights, which ultimately influences work place relationship. In terms of international Human Rights Law, at one time, governments dealt with those within their jurisdiction as they wished and resisted all criticisms of their actions by claiming that human rights were matters of "domestic jurisdiction". But with globalization, human rights are an established part of international law with an institutional structure to enforce them. In the study by Niles (1999) on a cross-cultural understanding of work-related beliefs, the author was able to identify certain work-related traits in Australia (a Western Christian country) and Sri Lanka (a non-Western and Buddhist country) using the protestant work ethics as a reference point. Data was collected using a questionnaire and the data from the test items were analyzed using factor analysis. Although, both cultures had the same idea of the concept of work, the Sri Lankans seemed to be more committed to hard work but had less belief that hard work leads to success compared to the Australians. However, over time, the author was able to uncover several proofs of a diffusion of certain aspects of the protestant work ethics across Sri Lanka (a non-Protestant and even non-Western country). This primary cause was ultimately traced to globalization. Similarly, Alam and Talib (2015) did a study on Islamic work ethics and individualism in a globalized workplace. The western capitalist approach to work ethics has been known to be more individual-centered (Individual incentives and rewards are given priority over group incentives and rewards). The basis for this is the notion that one should be proud of his own achievements and accomplishments and not just ride on the achievement of a group. On the other hand, the Islamic approach towards work ethics has been known to be more group-centered (employees are often rewarded as a group). One of the bases for this approach is the desire to promote team work and to promote common goals as superior to individual goals. The authors were able to prove that globalization has made Islamic work ethics to move away from collectivism and more towards individualism. Ladhari et al. (2015), in their study, were able to show some level of convergence of work ethics caused by globalization using a sample of three countries in different continents (Canada, Japan and Morocco). They tested for the existence of certain cultural values that extend beyond national borders among the three countries in the sample. The data on the cultural values were measured using the Horizontal-Vertical Individualism-Collectivism scale (a bit similar with Alam and Talib).

They found that although these countries had some aspects of culture that were specific to them, horizontal collectivism (tendency to cooperate and be rewarded collectively among peers) was consistent among all three countries.

Studies like that of Shirokanova (2015) give mixed results. Shirokanova (2015) did a comparative study on work ethics among Muslims and Protestants. The author tried to test Inglehart’s theory of post-materialist shift. This theory explains the societies’ change in values that occur as such societies develop. Since many societies experience similar socio-economic conditions (although at different times) they experience similar cultural, political and economic changes as they develop (Inglehart, 1997). During the modernization phase (i.e. the stage of revolutionary development), there is a highly committed attitude to hard work. However, during the post-modernization era of societal development (the period of diminishing marginal gain in material and subjective well-being), there is a shift from survival values (commitment to intense work and individualism) to well-being values (leisure and participatory management). The author also investigated whether the practice of protestant work ethics was limited to countries with a protestant religion. They conducted a survey on about 25,437 respondents in 55 different countries and discovered that living in a society that is predominantly protestant does not significantly increase commitment to hard work but belonging to a protestant religion does. This suggests that the adoption of the protestant work ethics depends more on religious identification than on mere migration policy. Also, they found that as countries develop, there is less commitment to hard work. The study admits to globalization having an effect on work ethics but from a religious perspective (i.e. a certain level of convergence of attitude towards work between protestant and Islam religion).

Convergence of work ethics across countries

Some of the studies that were reviewed were able to provide evidence of a convergence in work ethics among countries that originally had dissimilar attitude to work prior to globalization.

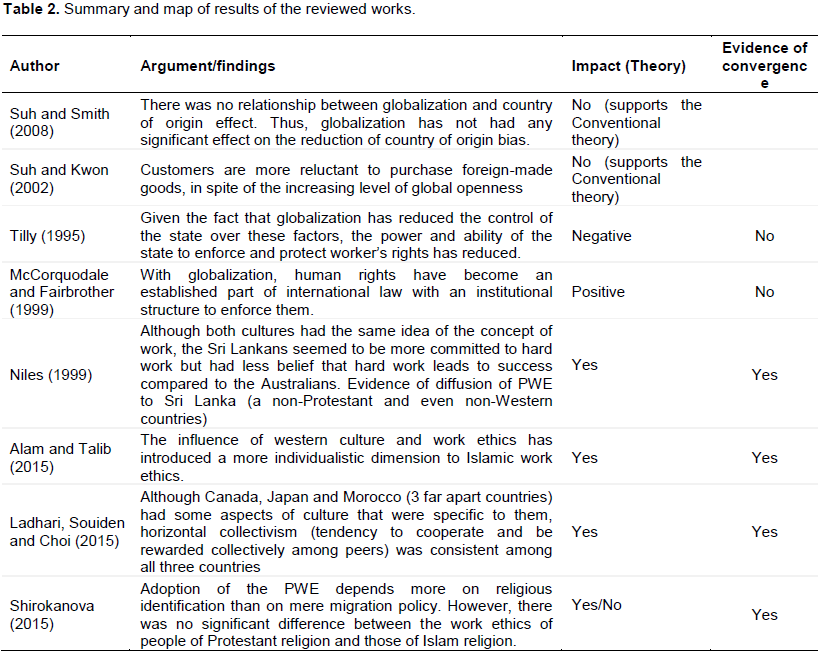

In the study by Niles (1999), Australia and Sri-Lanka were found to share similar idea of work. The author also discovered evidence of diffusion of some protestant work ethics traits to Sri Lanka over time and attributed it ultimately to globalization. Alam and Talib (2015) also proved that the influence of western culture and work ethics has introduced a more individualistic dimension to Islamic work ethics. They showed that globalization has caused a significant shift in Islamic work ethics to move away from collectivism and tend more towards individualism. In the study by Ladhari et al. (2015), the different countries (Canada, Japan and Morocco) were selected on the basis of continent dispersion and difference in cultural orientation. Over time, the work ethics in the three countries were found to share a culture of high horizontal collectivism which is characterized by high level of cooperation among colleagues. Shirokanova (2015), in her study, discovered that there was no significant difference between the work ethics of people of Protestant religion and those of Islam religion. The work ethics in about 55 countries of study were found to be similar regardless of the religion that the people practiced. This suggests some level of intermingling of work values and ethics. A summary of the results of the reviewed studies can be found in Table 2.

Work ethics is an element of a society’s culture and has been affected by globalization over the years. From the review of empirical literature, there are evidence of mixed results about the nature of this effect (Table 2). Some of the reviewed studies show that globalization has led several countries to adopt certain approaches to work ethics (both protestant and Islamic work ethics) thus creating overlaps of each approach across countries where they were previously foreign (Alam and Talib, 2015; Ladhari et al., 2015). Also, less developed countries tend to be more committed to hard work (Niles, 1999; Shirokanova, 2015). Globalization has also spread the awareness and enforcement of basic principles like fundamental human rights and other work place ethics (McCorquodale and Fairbrother, 1999), this spread is often restrained by existing barriers like country-of-origin bias, individual ethnocentrism and religious bias. This aligns with the suggestion of the dynamic theory of globalization. Religion was identified as a major mediating variable that determines the effect of globalization on work ethics (Shirokanova, 2015). On the other hand, few studies also confirmed the conventional theory that suggests globalization as an irrelevant (Suh and Smith, 2008; Suh and Kwon, 2002) or even negative factor in improving work ethics across borders, in so far as it limits the power of the state to properly enforce social policies (Tilly, 1995). Over all, out of the eight studies that were reviewed, three (3) confirmed the conventional theory (suggested a lack of positive influence of globalization on work ethics) while the other five (5) opposed the suggestions of the conventional theory.

Some of the recent studies that were reviewed were able to provide evidence of a convergence in work ethics among countries that originally had dissimilar attitude to work prior to globalization. Australia and Sri-Lanka tend to share similar idea of work (Niles, 1999). The work ethics in about 55 countries were found to be similar regardless of the religion that the people practiced (Shirokanova, 2015). The work ethics in Canada, Japan and Morocco were found to share a culture of high horizontal collectivism which is characterized by high level of cooperation among colleagues (Ladhari et al., 2015). Most of the sample countries in the reviewed studies are geographically far from one another and originally had different cultural orientations.

In this study, the concepts of globalization and work ethics were reviewed. The different perspectives of work ethics that have originated from different cultures and religions may have some flawed element, but also contain lots of virtues to be imitated in terms of attitude to work. The benefits of foreign cultural values and orientations will be realized only if countries, businesses and individual are more open to globalization. Although, barriers to globalization like ethnocentrism and country- exist, many of the reviewed empirical studies have revealed some impact of globalization on the work ethics of different countries. The more recent studies tend to suggest a significant impact of globalization on work ethics. This could suggest that such psychological biases may be strong but only effective in the short term. In the long run, globalization tends to overcome these barriers. Also the works that suggest significant impact of globalization on work ethics tested their hypotheses using larger respondents (larger sample size). This could suggest that those who hold these biases constitute the minority of individuals.

Some of the reviewed studies also showed evidence of convergence of attitudes to work and work place relationships. It is also important to mention that these results are not fixed. Since globalization is a continuous process, the findings of this study may be true as at the time of study but may change afterwards.

The results of the reviewed studies have some implications for countries, business organizations and individual workers. Contrary to the proponents of the conventionalist, globalization does affect the attitude to work at different levels and in different countries. In response, countries often establish policies to regulate the exchange of economic value across their borders. However, little effort is made in ensuring a moderate regulation of the transfer of socio-cultural and political values. These values should not be viewed with unnecessary skepticism since each culture has its good and bad sides. Instead of going to either extremes (allowing everything and allowing nothing), efforts should be put towards regulating what comes in. This will help in maximizing the good and minimizing the bad. Governments cannot afford to simply ‘fold their hands and hope for the best’. Development occurs through individuals, and so governments can establish immigration policies that attract individuals with certain dispositions to work that will promote both economic and cultural development. In the past few years, countries like Canada and Australia have begun to gear their immigration policies towards attracting certain quality of individuals and this has improved their economic performance in recent times. For this reason, it is no surprise that they are one of the countries that studies have found to exhibit some level of harmonization of work ethics. This increase in dynamics of work ethics can help in the character development of individual workers and this will only be realized if countries, businesses and individual are open to globalization.

Also, where there is convergence of work ethics, businesses will experience more dynamics in workers’ attitude. Such dynamics could be advantages as it could expose new ways of doing things that could improve on previous ways. Although, this new way of doing things may be obtained through technology transfer and other economic-oriented means. Work ethics still constitutes a major value creation element that can give a business competitive advantage across borders. For instance, many construction companies like to hire Germans because of their perceived orientation towards efficiency and toughness. And indeed, many of the top construction companies all over the world (both German and non-German) often have a number of German employees. Each category of attitude to work has its benefits and preferred context and thus convergence can bring about a more complete work environment compared to a work environment that possesses only one or the other.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTION

Despite the mostly positive intentions of its proponents, globalization is often hindered by some barriers. At the national level, Zinn and Grosse (1990) identified government policies and regulations (e.g. embargoes and legal restrictions placed on foreign products, ideas and values) as barriers to globalization. At the business perspective, Carrieri et al. (2013) identified poor functioning institutions, poor corporate governance and lack of transparent markets as significant barriers to globalization. All these factors limit effect of globalization on cultural development (particularly in the area of work ethics) and more studies could be carried out to investigate the effect of these factors on globalization and recommend possible solutions.

Also, a major limitation in the reviewed works is the measurability of the focal concepts. Globalization as a concept may be measured quantitatively using measures like the Globalization Index that measures the economic, social and political dimensions of globalization (KOF index), but work ethics is one that is difficult to capture from a quantitative perspective. Few of the reviewed studies measured work ethics partially, in terms of attitude towards foreign culture and values (e.g. individual ethnocentrism and country-of-origin effect).

Also, the more recent studies showed trend of convergence among some countries that are geographically far apart. Since globalization is a continuous process, the degree of this convergence may vary over time. Studies can be done to capture the degree of convergence work ethics across different countries over time.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ahmad S, Owoyemi MY (2012). The Concept of Islamic Work Ethic: An Analysis of Some Salient Points in the Prophetic Tradition. International Journal of Business and Social Science 3(20):116-123.

|

|

|

|

Alam MA, Talib N (2016). Islamic work ethics and individualism in managing a globalized workplace: Does religiosity and nationality matter? Journal of Management and Organization 22(4):566-582.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ali A (1988). Scaling an Islamic Work Ethic. The Journal of Social Psychology 128(5):575-583.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Baguma P, Furnham A (1993). The Protestant work ethic in Great Britain and Uganda. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 24(4):495-507.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Carrieri F, Chaieb I, Errunza V (2013). Do implicit barriers matter for globalization? The Review of Financial Studies 26(7):1694-1739.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Furnham A (1990). A content, correlational, and factor analytic study of seven questionnaire measures of Protestant work ethic. Human Relations 42(4):383-399.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gorz A (2001). Critique of economic reason: summary for trade unionists and other left activists. Global Solidarity Dialogue.

|

|

|

|

|

Heins V (1993). Weber's Ethic and the Spirit of Anti-Capitalism. Political Studies 41(2):269-283.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Inglehart R (1997). Modernization and Post-modernization. Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ladhari R, Souiden N, Choi YH (2015). Culture change and globalization: The unresolved debate between cross-national and cross-cultural classifications. Australasian Marketing Journal 23(3):235-245.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Manroop L, Singh P, Ezzedeen S (2014). Human resource systems and ethical climates: A resource-based perspective. Human Resource Management 53(5):795-816.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

McCorquodale R, Fairbrother R (1999). Globalization and human rights. Human Rights Quarterly 21(3):735-766.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mirels HL, Garrett JB (1971). The Protestant ethic as a personality variable. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 36(1):40-44.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nagashima A (1970). A comparison of Japanese and U.S. attitudes toward foreign products. Journal of Marketing 34:68-74.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Niles FS (1999). Toward a cross-cultural understanding of work-related beliefs. Human Relations 52(7):855-867.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

O'Gorman CS, Macken AP, Cullen W, Saunders J, Dunne C, Higgins MF (2013). What are the differences between a literature search, a literature review, a systematic review and a meta-analysis? And why is a systematic review considered to be so good? Irish Medical Journal 106(2):8-10.

|

|

|

|

|

Pope Francis (2020). Fratelli Tutti: Encyclical on Fraternity and Social Friendship, Rome: Orbis Books.

|

|

|

|

|

Robertson R, Lechner F (1985). Modernization, globalization and the problem of culture in world systems theory. Theory, Culture and Society 2(3):103-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Robertson R (2007). Globalization and Working Conditions: A Guideline for Country Studies. Unpublished, Washington, DC: World Bank.

|

|

|

|

|

Roth MS, Romeo JB (1992). Matching product category and country image perceptions: A framework for managing country-of-origin effects. Journal of International Business Studies 23(3):477-497.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Scherer AG, Palazzo G, Matten D (2009). Introduction to the special issue: globalization as a challenge for business responsibilities. Business Ethics Quarterly 19(3):327-347.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schütte H, Ciarlante D (1998). Consumer Behavior in Asia. New York: New York University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shirokanova A (2015). A comparative study of work ethic among Muslims and Protestants: Multilevel evidence. Social Compass 62(4):615-631.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Suh T, Kwon IG (2002). Globalization and reluctant buyers. International Marketing Review 19(6):663-680.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Suh T, Smith KH (2008). Attitude toward globalization and country-of-origin evaluations: Toward a dynamic theory. Journal of Global Marketing 21(2):127-139.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tian Q, Liu Y, Fan J (2015). The effects of external stakeholder pressure and ethical leadership on corporate social responsibility. China. Journal of Management and Organization 21(4):388-410.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tilly C (1995). Globalization threatens labor's rights. International Labor and Working-Class History 47:1-23.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Velho O (1997). Globalization: Object, Perspective; Horizon. In LE Soares (Ed.), Cultural Pluralism, Identity, and Globalization: 98-125. Rio de Janeiro: UNESCO.

|

|

|

|

|

Weber M (1930). The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. New York: Scribners.

|

|

|

|

|

Zinn W, Grosse R (1990). Barriers to globalization: Is global distribution possible? International Journal of Logistics Management 1(1):13-18.

Crossref

|

|