Using examples of tape recorded conversational data from fifty educated adult Igbo-English bilinguals resident in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, this paper demonstrates that lone English verbs are typically inserted into otherwise Igbo utterances by means of Igbo verbal inflectional morphology. Other verbs are adjoined to a helping verb from Igbo, specifically involving an adapted form. Yet, a few English verbs are inserted into a position corresponding to an Igbo verb without any adaptations. To answer the question as to why the verbal inflectional morphology of Igbo rather than that of English should be used, we show that this is predicted by the Matrix Language Frame (MLF) model, according to which integration into the bound morphology of the base language is expected. Also, the paper identifies that the un-adapted English verbs occur in Igbo serial verb constructions (SVCs). The only type of structure where a full Igbo verb may occur without verbal morphology. Consequently, this paper concludes by arguing that the un-adapted English verbs in Igbo SVCs do not occur in codeswitching (CS) because of the activation of a ‘CS-specific’ compromise strategy, rather they, like the English verbs bearing Igbo verbal inflectional morphology occur in clause structure with restrictions imposed by the base language grammar.

Unless otherwise acknowledged, the examples of lone English verb insertions in otherwise Igbo utterances discussed in the paper come from the conversational CS data collected in the summer of 2011 from 50 educated adult Igbo-English bilinguals resident in the city of Port Harcourt, Nigeria (Ihemere, 2016). Since CS occurs most frequently in informal conversations among in-group members (Deuchar, 2005, 2006; Eze, 1998; Gumperz, 1982; Park, 2000; Poplack, 1980), the social network method based on a pre-existing friendship network was used for the data collection.

The main advantage of this methodology is that the researcher can attach him/herself to a group and, by making use of the group dynamics which influence patterns of language use, obtain very much larger amounts of spontaneous speech than is generally possible in interaction with a single individual who is isolated from his/her customary social network (Milroy, 1987: 35). Furthermore, as Ihemere (2016: 72) observes, the social network method permitted the collection of authentic natural language in interactional situations. The entire corpus contains many examples of different types of CS. In this paper, however, the central focus is on characterizing the strategies used by Igbo speakers to insert lone English verbs in otherwise Igbo utterances.

The nature of Igbo verbs

Drawing on Ihemere (2016: 58-62, 68-69), Igbo verbs like those of English are found immediately preceding their complement(s) in the verb phrase (VP). The verbs can be classified as either active or stative. Active verbs are used for expressing action or activity, while stative verbs (e.g. the copulas: bụ, wụ dị and ná») are used for expressing qualities/states and existential notions of being. There are also several auxiliary verbs which are unlike those of English. For instance, they are all bound morphemes in the language. That is, an Igbo auxiliary verb can only be used in obligatory combination with a verbal derivative which makes it complete and meaningful. Emenanjo (1978: 127) gives a list of seven such Igbo verbs. Here, however, we only list the three that are used by the speakers in the examples (Ihemere 2016: 58-59):

(i) na- marks the progressive:

(a) Progressive affirmative

Nnenna na-a-bịa

AUX-V-come

‘Nnenna is coming’ (‘Nnenna usually comes’)

(b) Progressive negative

Nnenna a-na-ghị a-bịa

V-AUX-NEG V-come

‘Nnenna is not coming’ (‘Nnenna does not usually come’)

(ii) ga- marks the future:

(a) Future affirmative

Nnenna ga-a-bịa

AUX-V-come

‘Nnenna will come’ (‘Nnenna is going to come’)

(b) Future negative

Nnenna a-ga-ghị a-bịa

V-AUX-NEG V-come

‘Nnenna will not come’ (‘Nnenna is not going to come’)

(iii) gaa- marks the unfulfilled:

Nnenna gaa-ra a-bịa

AUX-IND V-come

‘Nnenna should have come.’

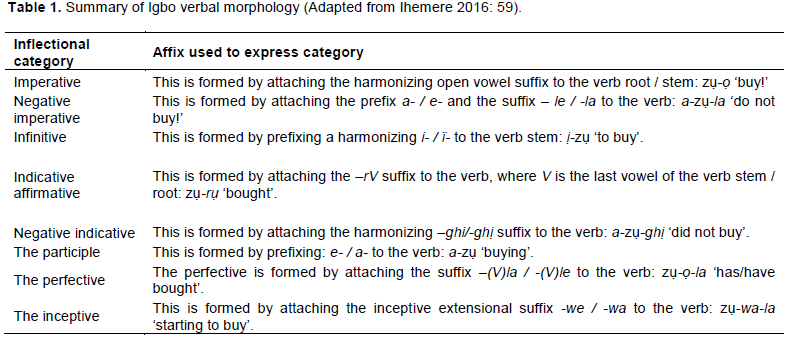

The Igbo bound auxiliary verbs behave like modals in English because they mark tense and aspect and assist to differentiate the different verbal constructions. Furthermore, it is important to point out that the verb is the only grammatical category in Igbo that can take inflectional affixes, shown in Table 1.

Note also that Igbo has three dependent, short and weak pronouns: ị-/i- ‘you (2nd sg)’, á»-/o- ‘he/she/it (3rd pl) and a-/e- ‘some person(s) (non-person-number specific or non-definite)’. Each of the three weak PRNs has two forms and each form is conditioned by the vowel quality of an immediately following verbal element (Ihemere, 2016); this will give a detailed discussion of vowel harmony in Igbo. Given the restricted subject position of occurrence of the pronominal forms, we shall analyse them as pronominal subject clitics (CL for short). Borer (1986) notes that clitics serve as syntactic constituents but are phonologically bound to adjacent elements of lexical categorial status. However, different from lexical items clitics do not constitute prosodically autonomous elements and in this regard, they pattern like affixes (see the descriptions of Igbo affixes in Table 1). Also, the dependent, short and weak pronouns in Igbo can be viewed as special clitics (Zwicky, 1977) since they appear at the subject position before verbal elements as proclitics (Anyanwu, 2012). Some examples of the Igbo subject CLs in constructions are as follows:

(2) á»-da-ra ule

3SG.CL-fail-IND exam/test

‘He/she/it failed (the) exam/test’.

(3) ị-zụ-rụ efe

2SG.CL-buy-IND shirt/dress

‘You bought (a/the) shirt/dress.’

(4) a-rụ-rụ ụlá»

CL-build-IND house

‘Someone built a house.’

Anyanwu (2012) observes that the Igbo dependent pronominal elements can only occupy pro-argument positions in the constructions where they appear, though superficially they seem to appear at subject argument position. Furthermore, he states that the Igbo pronominal subject clitics possess the features of pro in pro-drop languages (Ihemere, 2016: 68-69). We will return to these clitics in subsequent sections of this paper. It will suffice to say for the moment that all Igbo verbs obligatorily receive verbal inflectional morphology, except in serial verb constructions (SVC) where some verbs may appear bare (that is without verbal inflectional morphology).

Amaechi (2013: 156-157) observes that verb serialization is a syntactic resource which allows the speaker to express various aspects of a situation as a single cognitive package within one clause and with one predicate. An important feature of SVC is that the sequence of verbs shares the same subject noun phrase. They may have an intervening object between the verbs as illustrated in the Igbo example.

(5) o jiV1 aka vá»á»V2

He hold hand weed

‘He used his hands (to) weed.’

In Example 5, the object of V1 is understood as the object of V2 in the clause; and both verbs share the same subject in the example. Crucially, Ihemere (2016: 61) identifies that Igbo serial verbs have the following properties:

(a) The two or more verbs with their complement (if any) in an SVC do not have any marker of coordination or subordination (Amaechi, 2013: 157).

(b) The verb phrases (VPs) in the sequence are construed as occurring within the same temporal frame. Some verbs may appear with or without morphology that indicates past tense, but the sentence obligatorily receives a past interpretation (Example 5).

a. Auxiliaries, negation, tense and aspect markers of the sequence of verbs are found with the first verb

b. of the SVC. However, extensional affixes and the open vowel suffix may be found on the other verbs in the SVC, as in Example 6 (Ihemere, 2016: 61):

(6) ỠgaV1-ra ahịa zụV2-Ỡefe

She go-IND market buy-V dress

‘She went to (the) market and bought (a) dress.’

In the language, there are different types of serial verbs as outline briefly after Ihemere (2016: 62):

Instrumental SVC: The verbs ji ‘hold’ and were ‘take’ are used to express instrumentality in Igbo. Both verbs are said to be syntactically similar and occur in a complex structure [- NP VP], typical of SVCs, where it obligatorily takes a complement and a VP. We see this in Example 5, where the object of V1 aka ‘hand’ is also the instrument used to carry out the action of V2.

Multi-event SVC: In a multi-event SVC different events which are related are formed and all the verbs share a single subject. This is illustrated in Example 6.

Dative SVC: Igbo dative SVCs indicate and distinguish the recipient of something given or transferred. They normally surface as V-V compounds, as in Example 7.

(7) ỠzụV1-ta-ra efe nyeV2 m

She buy-ENCL-IND dress/shirt give 1SG.ACC

‘She bought (a/the) dress/shirt (and) gave (it to) me.’

Resultative SVC: In Igbo, resultative SVCs like dative constructions also surface as V-V compounds as in Example 8 (Ihemere, 2016: 62):

(8) Nze meV1-re nwunye ya a-zụV2-Ỡefe

Nze make-IND wife his V-buy-V dress

‘Nze made his wife to buy a dress.’

It was observed in Example 8 that V2 expresses the result of V1 and the object of V1 is seen and understood to be the subject of V2. With respect to the analysis reported in this paper, it is only in SVCs that a full Igbo verb that may appear without verbal inflectional morphology. Therefore, our expectation is that all lone English verbs used in Igbo utterances will obligatorily receive Igbo verbal inflectional morphology apart from those found to occur in serial verb constructions.

INSERTING LONE ENGLISH VERBS IN OTHERWISE IGBO UTTERANCES

Concerning the earlier stated aims and objectives in the introduction, lone English non-finite verbs are inserted in Igbo in two main ways:

(1) The verbs are either inserted in synthetic constructions, where the sole verb is inflected for tense, aspect and negation by the base language, or

(2) They are inserted in periphrastic constructions in which the finite auxiliary comes from the base language (Ihemere, 2016: 130).

In the sections that follow immediately, attention is turned to illustrating how the these two strategies are effected in Igbo-English bilingualism.

Insertion by Igbo verbal inflectional morphology

The following are some utterances from Igbo-English which illustrate the integration of English verbs by means of Igbo verbal inflectional categories (Table 1).

(9) ha miss-ị-rị flight ha…

they miss-V-IND flight ha

‘They missed their flight…’

(10) maka na ha register-ra na the wrong desk …

C C they register-IND PREP the wrong desk

‘because they registered at the wrong desk…’

(11) ma ha book-ụ-rụ na hotel

but they book-V-IND PREP hotel

‘but they booked into (a) hotel’

Examples 9 to 11 make it very clear that the English verbs are not finite forms because the speaker’s intentions call for a past tense marking, but miss-ed, register-ed and book-ed do not occur; the past meaning comes only from the base language inflectional morphology that the English verbs do not influence. Other examples from Igbo-English are given in Examples 12 to 15.

(12) ha a-qualify-ị-ghị

They V-qualify-V-NEG

‘They did not qualify.’

(13) anyị ga-e-kick ha niile out of office

we AUX-V-kick them all out of office

‘We will kick all of them out of office.’

(14) o clean-ị-cha-la moto gi

she clean-V-ENCL-PERF (motor) car your

‘She has finished cleaning your car.’

(15) á»-na-a-chỠị-start ngwa ngwa

CL-AUX-want INF-start quick quick

‘She wants to start quickly.’

In these examples, the ML only supplies all the relevant inflectional morphology on the singly occurring English verbs. The negative inflection -ghị and the verbal paricles in Example 12, the auxiliary ga- and the vowel particle in Example 13, the perfective suffix –la, enclitic (meaning ‘completely’) and verbal particle in Example 14, and the infinitive prefix ị- in Example 15.

Ihemere (2016) observes that in various studies investigating the insertion of verbs from one language into another, researchers such as Backus (1996: 212), Deuchar (2005: 263-267), and Myers-Scotton and Jake (2014: 8) have noted that such verbs are usually non-finite but are made finite by ‘matrix (or base) language means’. Myers-Scotton and Jake (2014: 8) observe that the reason why non-finite EL verbs are easily inserted in CS structure is due to the fact that non-finite verbs do not carry the same costs as finite forms because their levels of predicate-argument structure and/or morphological realization patterns are not salient in structure building. Furthermore, they opine that these EL non-finite verbs only salient level of abstract structure is the level of lexical-conceptual structure. Therefore, such verb forms as infinitives and present participles can take ML verbal inflections without creating any congruence problems regarding the abstract levels referring to grammatical structure.

Taking the insertion of believe in Example 16, we can illustrate the language production process involved in the insertion of mixed verbal expressions in Igbo-English intra-sentential CS.

(16) anyị believe-ụ-rụ na ihe ha kwu-ru na ….

we believe-V-IND PREP thing they say-IND PREP

‘We believed in the thing they said at …’

Stage 1: Conceptual (lemma level)

(1) Once a speaker selects an English content morpheme, such as the verb believe in Example 16 during Igbo-English CS, he/she also selects Igbo as the ML of the mixed verbal expression under production.

(2)The ensuing processes are triggered to commence the building of an appropriate grammatical slot for believe in the clause:

(i) believe is checked for congruence with its Igbo counterpart kwee at the three levels of abstract lexical structure:

(a) lexical-conceptual structure: closest to the speaker’s intentions;

(b) predicate-argument structure: deals with how thematic structure is mapped on to

grammatical relations; and

(c) morphological realization patterns: this is where the morpheme order and system

morpheme criteria apply.

(3) Information from all three levels are sent to the formulator (including information about the full abstract lexical structure of the Igbo counterpart of believe =kwee).

Stage 2: Formulator: The formulator decodes the information sent from the lemma level

(1) Regarding lexical-conceptual structure, the formulator identifies that believe and kwee are sufficiently congruent because:

(a) They encode identical concept, that is, they have analogous lexical-conceptual structure;

(i) They have the same predicate-argument structure:

(b)They are both verbs (believe is used as a transitive verb in Example 16: ‘the speaker considers what is being said in the example to be true’) that assign the same thematic roles to their arguments, i.e. to the subject (Agent) and to the object (Patient);

(2) In relation to morphological realization pattern, they both require no case-marking of their arguments;

(a) Igbo is the language in control of functional level processes, therefore the late system morpheme criterion ensures that only Igbo supplies all the required inflectional morphology in the mixed verbal expressions.

(b) In Example 16, for instance, believe receives the Igbo indicative affirmative inflection marking past tense.

(c) Also, the morpheme order criterion ensures that Igbo morphosyntactic procedures are used in framing the mixed verbal expression. Igbo, like English, is typically an SVO language as reflected in the above examples. Hence, there is no conflict in word order in the examples as far as the switched elements are concerned.

Stage 3: Surface realization

Consequently, believe in Example 16 is inserted into the verbal slot intended for the Igbo verb kwee.

Insertion by pronominal subject clitics and verbal inflectional morphology

As outlined earlier on the nature of Igbo verbs, the language has three singular, three plural and one impersonal pronoun. The three singular pronouns have each an independent and dependent form. In some contexts, the place of the pronoun can be occupied by what may be called a pronominal prefix (or pronominal subject clitics (PSC), after Anyawu (2012), i-/ị- ‘you (singular)’, o-/á»- ‘he/she/it’ and a-/e- ‘nonperson-number specific’, harmonizing with an immediately following verb stem vowel. As PSCs, they can only occupy pro-argument positions in the constructions where they appear in subject argument position.

The Igbo PSCs, like pronominal subject clitics in French (Jaeggli, 1981), must be adjacent to either the main or auxiliary verbs unlike the independent pronouns and lexical NP subjects, which pattern differently (Anyanwu, 2012: 379-380):

(17a) Ọ-*naanị ga-ra ahịa

3SG.CL only go-IND market

(17b) Eze/Unu naanị ga-ra ahịa

Eze/2PL.PRN only go-IND market

‘Only Eze/you went to market.’

Example 17a is unacceptable because the Igbo PSC is split from the verb by the introduction of naanị ‘only’, which can correctly post-modify an Igbo noun or pronoun, as in Example 17b. Another feature of the Igbo PSCs is that they always occur on their own without modification, while the independent pronouns can be modified by numerals, as shown in Example 18 (Anyanwu, 2012: 380):

(18a) Ọ- *atá» ka ha chá»-rá»

3SG.CL NUM FOC 3PL want-IND (self benefactive)

(18b) Ya atá» ka ha chá»-rá»

3SG NUM FOC 3PL want-IND (self benefactive)

‘It is the three (of them) that they want.’

Unlike both lexical NPs and independent pronouns, Igbo PSCs cannot be topicalized. This accounts for why Example 19a is ungrammatical (Anyanwu, 2012: 380).

(19a) *Ọ-, ka Ada nye-re ego

3SG.CL FOC Ada give-IND money

(19b) Ya/Ha/Unu/Eze, ka Ada nye-re ego

3SG/3PL/2PL/Eze FOC Ada give-IND money

‘It is him/they/you/Eze that Ada gave money.’

In Igbo, both the independent pronouns and lexical NPs can be clefted, but the PSCs cannot as indicated by the ungrammaticality of Example 20a (Anyanwu, 2012: 380).

(20a) *Ọ bụ á»- ka Ada nye-re ego

It BE 3SG.CL FOC Ada give-IND money

(20b) Ọ bụ ya/ha/unu/Eze ka Ada nye-re ego

it BE 3SG/3PL/2PL/Eze FOC Ada give-IND money

‘It was him/them/you/Eze that Ada gave (some)

money.’

Whenever there is emphasis on the subject, an independent rather than a PSC is used. This can explain the unacceptability of Example 21a (Anyanwu, 2012: 380).

(21a) *Ọ- bịa!

3SG.CL come!

(21b) Ya/Unu/Ha bịa!

3SG/2PL/3PL come

‘Let him/you/them come.’

An Igbo PSC cannot be conjoined with an independent pronoun or lexical NP. This is unlike the independent pronouns and lexical NPs that can be conjoined with each other, as in Examples 22a-c (Anyanwu, 2012: 380).

(22a) *Ọ- na Ada bịa-ra

3SG.CL and Ada come-IND

(22b) Ya na unu bịa-ra

3SG and 2PL come-IND

‘S/he and you came.’

(22c) Ya/Ha na Ada/gị bịa-ra

S/he/they and Ada/you come-IND

‘S/he/they and Ada/you came.’

With these information in mind, consider the singly occurring English verbs in Examples 23 to 26 from Ihemere (2016: 136-137).

(23) á»-study-rị na London in the 70s

3SG.CL-study-IND PREP London in the 70s

‘He studied in London in the 70s.’

(24) ị-sị na ị-lodge-ị-rị na guest house ahụ

2SG.CL-say C 2SG.CL-lodge-V-IND PREP guest

house DEM

‘You said that you lodged in that guest house.’

(25) e-send–ị-rị invitation card iri

CL-send-V-IND invitation card NUM

‘(Some person/s) They sent ten invitation cards.’

(26) e-decorate-ị-rị hall aná»

CL-decorate-V-IND hall NUM

‘(Some person/s) They decorated four halls

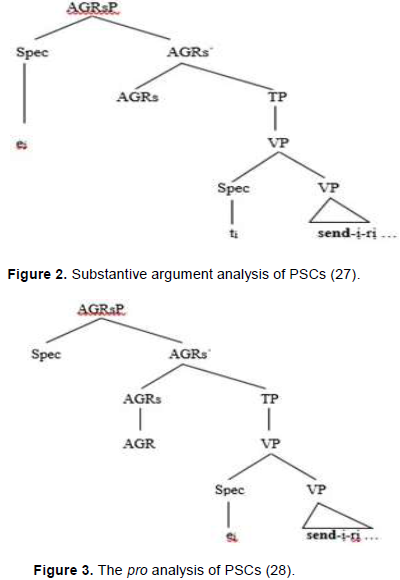

Ihemere (2016) suggests that the PSCs can be analyzed in two ways. They can be analyzed just like the English subject pronouns, in which case the PSCs are arguments in the spec of AGRsP, as in Example 27, representing the structure in Example 25.

The structure in Figure 2 (Example 27) represents the ‘substantive argument analysis of PSCs’ (Anyanwu, 2012: 383). It can be argued that the PSC is generated at Spec, VP from where it raises to Spec, AGRsP for nominative case marking. Additionally, given the morphosyntactic status of the PSCs outlined above the argument analysis implies that the subject pronominal clitic having undergone a Spec-to-Spec move operation is at some point lowered to AGRs by a syntactic operation or by a purely phonological process of cliticization (Ihemere, 2016: 137).

On the other hand, it can be argued that the PSCs cannot occupy Spec, AGRsP argument position but just a mere functional element generated at AGRs which, identifies a null pronominal in subject position (cf. Rizzi 1986, cited in Anyanwu 2012: 383). This type of analysis, the pro analysis Figure 3 (Example 28), entails that the PSC is base generated at AGRs while its Spec, AGRsP is occupied by pro. Thus, the PSC is a spell-out of subject agreement features (cf. Campbell 1998, cited in Anyanwu 2012: 383; Ihemere, 2016: 137-138).

The examples just considered clearly demonstrate that the base language (that is, Igbo) is in complete control of how verbal inflectional morphology is realized in Igbo-English CS. That is, as Ihemere (2016: 133-134) notes, the examples appear to confirm the view expressed by Myers-Scotton and Jake (2014: 7) that the EL is active in CS at the level of lexical-conceptual structure, when an EL verb is selected as the lemma that best satisfies the speaker’s intentions, the EL verb brings along its meaning, but it is the ML that integrates it into predicate-argument and morphological realization patterns. In other words, how thematic roles are realized in the syntax is determined by the base language.

Lone English verbs inserted without Igbo verbal inflectional morphology

Here, we account for the lone English verbs in otherwise Igbo utterances inserted without any verbal inflectional morphology. Such verbs are termed ‘bare forms’ in the literature. Recall from the discussion in the section above, on the nature of Igbo verbs, that, in Igbo, verb serialisation is the only situation when a full Igbo verb may appear bare (that is, without verbal inflectional morphology) as one of a succession of verbs. That the first verb in the series is usually marked for temporal reference. However, we must note that it is not the case that every initial verb in a SVC bears morphology. Some verbs in a SVC may take extensional affixes. Crucially, an important feature of SVCs in connection with Igbo is that one of the verbs bears morphology while the others may occur as bare forms. As it turns out, all the bare EL verbs in our examples occur in SVCs.

Several of the lone English verbs occur in ‘multi-event SVCs’. In this type of SVC, different events which are related are formed; and all the verbs share a single subject as in (29-31) from Ihemere (2016).

(29) o-meV1-re campaignV2 nyeV3 anyị

CL-do/make- IND campaign give us

manifesto ya

manifesto his

'He campaigned and gave us his manifesto.'

(30) commissioner abụỠkaV1 e-meV2-re arrestV3

commissioner two BE V-do/make-IND arrest

kpá»rá»V4 gaV5-wa Abuja

take go-ENCL Abuja

‘Two commissioners were arrested and taken to

Abuja’

(31) councillor anyị baV1-ra government bidoV2

councillor our enter-IND government start

meV3-we embezzleV4 ego

do/make-INCP embezzle money

‘Our councillor entered government and started to

embezzle money.’

Other EL verbs in the data occur in what is termed instrumental SVC, as in Examples 32 and 33 (Ihemere, 2016).

(32) mụ na nwunye m jiV1 aka anyị meeV2

Me/I and wife my hold hand our do/make

dismantleV3 the leaking roof

dismantle the leaking roof

‘My wife and I dismantled the leaking roof with our

hands.’

(33) e-jiV1 ha ụgbỠm̩ miri meeV2 surveyV3 ebe

CL-hold they vehicle water do/make survey place

a-gaV4-a-rụV5 oil rig ahu

V-FUT-V-build oil rig ahu

‘They used a water vehicle (ship) to survey the

location where they will build that oil rig.’

In Igbo, the verb ji ‘hold’ is used to express instrumentality and it usually occurs in a complex structure [- NP VP], typical of SVCs, where it obligatorily takes a complement and a VP, as in Examples 32 and 33. For instance, the object of V1 aka anyị ‘our hands’ in Example 32 is also the instrumental argument of V3.

Example 34 occurs in what may be termed a dative SVC.

(34) nwunye m gaV1-e-meV2 gị inviteV3 gwaV4-kwa

wife my FUT-V-do/make you invite tell-ENCL

gị ụbá»chị m gaV5-a-pụV6-ta á»rụ

you day I FUT-V-leave-ENCL work

'My wife will invite you and tell you what day I will get

off work.’

In Igbo, dative constructions typically surface as V-V compounds; and indicate/distinguish the recipient of something given or transferred, as in the above example. The fourth type of SVC is the resultative SVC, as in (35) below.

(35) o-meV1-re m̩ma ya sponsorV2 ya a-gaV3

3SG.CL-do/make-IND mother his sponsor she V-go

Canada

‘He sponsored his mother and she travelled to Canada.’

As in monolingual Igbo resultative SVCs, in example 35, we observe that V3 expresses the result of V2 and the object of V1 is regarded and understood to be the subject of V3. Additionally, in the example, V2 is analysed as incorporating into V1 to give the complete predicate.

An important feature of verb serialization in Igbo according to Ihemere (2016: 152) is that the sequence of VPs in the construction act together as a single predicate,

without any marker of coordination, subordination, or syntactic dependency of any kind. This is exactly the situation with all the verbs in the bilingual SVCs. For instance, the verbs me-re ‘did’, campaign and nye ‘give’ in Example 29; ka ‘copular’, e-me-re ‘did’, arrest, kpá»rá» ‘take’ and ga-wa ‘start to go’ in Example 30; ba-ra ‘entered’, bido ‘start’, me-we ‘start to do’ and embezzle in Example 31; ji ‘used’, mee ‘do’ and dismantle in Example 32; ji ‘used’, mee ‘do’ and survey in Example 33; ga ‘will’, mee ‘do’, invite, and gwa ‘tell’ in Example 34; and me-re ‘did’ and sponsor in Example 35, are all contained within a single clause (as far as Igbo is concerned). As well, the verbs share syntactic subject and object within their clauses.

Conversely, in the monolingual English translations of the same examples, the mono-clausal bilingual SVCs are expressed as multi-clausal constructions linked by the conjunction ‘and’. Also, other elements of the mono-clausal bilingual SVCs now appear in the monolingual English translations as DP complement of a PP in Example 32, ‘with our hands’ and ADV clauses in Example 33, ‘… where they will build that oil rig’; and Example 34, ‘… what day I will get off work’.

Also, in the monolingual English translations of Examples 31 and 33, the English verbs embezzle and survey appear as ‘to + infinitive’ construction. This is absent in the bilingual SVCs where the two verbs are not inflected with the Igbo infinitive prefix ị-. Thus, the structural configuration of the bilingual SVCs resembles that of Igbo (see the monolingual Igbo SVCs in Examples 5 to 8) rather than English (Ihemere, 2016: 152).

As well, we noted earlier that in Igbo SVCs the VPs in the sequence are construed as occurring within the same temporal frame. Some verbs in the series may appear with or without morphology. Auxiliaries, negation, tense and aspect markers of the sequence of verbs are found usually with the first verb of the SVC. These requirements, it would seem, can account for why all the English verbs in the earlier examples occur without the base language verbal morphology even though a past or future tense reading is implied. Notice that in the monolingual English translations the EL verbs receive the appropriate finite verb inflections, which are missing in the bilingual SVCs. Moreover, we can observe in the bilingual SVCs that auxiliary, negation, tense and aspect markers are found with the first verb in the series. For example, the Igbo auxiliary verb ka ‘BE’ in Example 30, the –rV indicative affirmative suffix on the Igbo verb me ‘do’ in Examples 29, 30, and 35, on ba ‘enter’ in Example 31; and the Igbo bound auxiliary ga- and the verbal particle e- on me ‘do’ in Example 34. In Examples 32 and 33, the Igbo instrumental verb ji ‘hold/use’ is bare but obligatorily receives a past tense reading. From this, it seems that the English verbs are bare only because this is what is expected according to the grammar of Igbo, the ML (Ihemere, 2016: 152-153).