ABSTRACT

The main objective of the study is to analyze the errors in billboard advertisements written in Afan Oromo in Jimma town. There are many writing problems on most of the billboards in the town. However, the data collection for this study focused only on the errors that totally changed the meaning of the words and phrases and affected communication. In order to achieve the main objective, three specific objectives related to the types of errors in the writings of the billboards, the extent to which the errors affect communication, and the negative impacts of the errors on the development of the language were formulated. The data for the study were collected through observation. The collected data were analyzed qualitatively. The result of the study shows that letters are misspelled in most words of the advertisements as a result of which the word meaning is changed to an unintended one, in most phrases or sentences in which double adjectives were used, the adjectives were disordered and the sentences or phrases became meaningless, and some phrases or sentences are directly translated from Amahric to Afan Oromo which is not correct because Afan Oromo has its own rule. The errors have no specific purpose or they were not to attract attention of the consumers to the product. Generally, it is possible to say that the errors are high in magnitude because they not only affect communication but also they have negative impact on development of the language (Afan Oromo). Hence, Jimma University, specifically, Afan Oromo Department, should work cooperatively with the culture and tourism office of the town and other concerned bodies to mitigate the writing problems observed in the town because teaching the language (Afan Oromo) alone cannot develop the language, but it requires a perpetual follow up of how people are using the language.

Key words: Bill board advertisement, Afan Oromo, error, professionals, adjective, phrase, morpheme, derived adjectives, intended meaning, diverted meaning, inscribers, anonymity.

Afan Oromo is the most widely spoken language in the family of Cushitic branch, and the most populous language of Ethiopia (Roba, 2004). Afan Oromo is the official language of Oromia Region, and it is used in education, administration, justice and the media apart from being the lingua franca in the vast wide areas in the country (Getachew and Derib, 2006). It is used as a medium of instruction in elementary schools (Grade 1 to 8) and in the teachers’ education colleges of the region. It is being taught as subjects from grade 1 to 12. Moreover, it is offered in different Ethiopian universities from first degree up to post graduate level.

Afan Oromo uses the Latin script instead of the Amharic letters based on linguistic, pedagogical, and practical issues reasons (Tilahun, 1992). It has 33 characters (letters) and writing using the language (Afan Oromo) requires knowing how these characters can be used (spelled). In Afan Oromo, we use double vowels for long sound and we use double consonant for long consonant. A doubled vowel makes the vowel long and can often change the meaning of the word, as in lafa (“ground”) and laafaa (“soft”) (http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Afaan_Oromo/Alphabet). On the other hand, consonant length is often indicated by writing a consonant twice ("ss", "kk", "pp", and so forth) and its length can distinguish words from one another, for example, badaa ('bad'), baddaa ('highland') (http:// en. wikipedia. org /wiki / Gemination). This shows that in Afan Oromo, length is lexically distinctive both with vowels and consonants.

The position of adjective is also different in Afan Oromo sentence or phrase when compared with the position of adjective in Amharic or English sentences. Unlike in the two languages, in Afan Oromo, adjectives are used after the noun or pronoun which they modify (Getachew, 2011). For example, in the phrase ‘Nama dheeraa’ (Tall man), the adjective dheeraa (tall) is used after the noun nama (man).

Moreover, word order in Afan Oromo sentence is different from that of English. Afan Oromo sentence follows Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) format (http:// en.wikibooks.org/ wiki/ Afan_Oromo/ Chapter_02). Example:

“He loves football” (SVO) → “Inni kubbaa miillaa jaallata” (SOV).

From the earlier mentioned points, we can understand that someone who wants to write in Afaan Oromo should have the necessary skill and knowledge of writing at least on the earlier mentioned issues about the language. This is because good writing should follow all the rules of a language (http://examples.yourdictionary.com/bad-grammar-examples.html.

However, most of the time, intentionally or unintentionally, people make mistakes when writing using the language (Afan Oromo). For example, most billboard advertisements written in Afan Oromo in Jimma town do not seem to have been written by the writers who know the issues explained above about the language because the writings are full of errors. The errors have no specific purpose (they are not stylistic innovations).

Regarding this, Amanuel (2012) conducted a case study on Jimma town’s linguistic landscape inscribers’ attitude toward Afan Oromo. His findings showed that the inscribers’ lack of knowledge on the language and their negative attitude toward the language are the root causes of the errors.

In this survey research, the researcher wanted to see the magnitude of the errors in billboard advertisements written in Afan Oromo in Jimma town. Accordingly, this study intends to answer the following research questions:

1. What are the types of errors in the writings of the billboards?

2. To what extent the errors affect the intended communication?

3. Do the errors have negative impact on the development of the language?

Survey based cross-sectional study was carried out in Jimma town from January, 2015. Jimma is one of the Oromiya zones and it is located in south west of Ethiopia. It is 352km away from the capital of Ethiopia. Afan Oromo is a native language in the zone. That is why most billboard advertisements are written in Afan Oromo in the town in addition to Amharic. Nineteen (19) billboards on the main streets were surveyed and data were collected for the study. The data for the study were collected through observation. Thus, the writings on the billboards were assessed on the basis of the already prepared check list. The questions on the check list were pre tested and they were used after they were proved to be valuable.

Though there are many writing problems on most of the billboards in the town, the data collection focused only on the errors that totally changed the meaning of the words and phrases and affected the communication. Since the intention of the paper was to see the magnitude of the errors, the researcher did not want to conduct interview with copy writers, advertising professionals and the consumers of the advertised messages. Even though the interview was not conducted with copy writers, it is clear that the errors have no specific purpose, or they were not used to attract attention of the consumers to the product.

The name Abebe in the data is not the actual name taken from the billboards, but it is used as a code to preserve the anonymity of the owners of the billboards. The data obtained from the billboards about the topic under the study were analyzed using descriptive method. Since the study is purely descriptive, the result of the study is reported qualitatively.

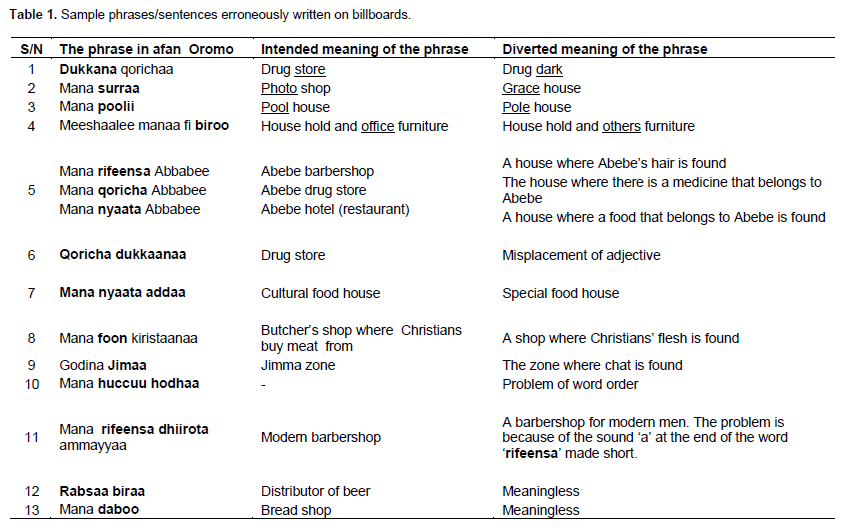

Sample phrases /sentences erroneously written on billboards. The word/s with a problem in each phrase/sentence is/are written in bold are listed in Table 1.

Below is the analysis of the data in Table 1. The words and phrases in Afan Oromo are made bold in the analysis to distinguish them from the English words/phrases. The word ‘Dukkaana’ in Afan Oromo represents the word ‘store’ which ‘Dukkaana qorichaa’ means ‘drug store’. The vowel ‘a’ sound should be long (aa), otherwise, if we make the vowel ‘a’ short as ‘dukkana’, it gives different meaning ‘dark’ and changes the meaning totally.

The words ‘Surraa’ and ‘Suura’ are different in meaning. ’Surraa’ means grace and ‘Suura’ means photo in Afan Oromo. This difference has come because of long and short consonant sound. As can be seen in the above table, the writer wanted to say ‘photo shop’ but because he/she made the consonant ‘r’ long, the meaning is changed to other_ ‘Grace house’ which is a total change in meaning (Appendix 1).

The word ‘poolii’ is also wrongly used to refer to ‘pool’. Afan Oromo word is read as written following the spelling. ‘Poolii’ is a word with long ‘o’ sound in the middle and long ‘i’ sound at the end and can be read as it is. Its equivalent meaning in English is ‘pole’. In writing this, the writer wanted to write the word with long ‘u’ sound in the middle and long ‘i’ sound at the end_ ‘puulii’. So, the intended phrase is ‘mana puulii’ which means ‘pool house’, but the meaning is changed to other - ‘pole house’ because of the discussed problem.

The phrase ‘Meeshaalee manaa fi biroo’ has also a meaning defect as result of a sound problem in the word ‘biroo’. The intension was to write as ‘Meeshaalee manaa fi biiroo’ which means ‘House hold and office furniture’. The word ‘biroo’ in Afan Oromo represents the word ‘Others’. The intended meaning can be obtained if the same word is written with a long ‘i’ sound next to the consonant (letter) ‘b’. Since the vowel ‘i’ sound is made short, the meaning of the phrase is changed from ‘a house hold and office furniture’ to ‘house hold and others furniture’.

In the phrases ‘Mana refeensa Abbabee’, ‘Mana nyaata Abbabee’ and ‘Mana qoricha Abbabee’, the words used after the word mana (house) were assumed to function as adjectives to modify the word mana (house). Nevertheless, the vowel ‘a’ sound at the end of each word is made short as a result of which the meaning is changed. Contrary to the writer’s intension, the words are functioning as a noun rather than as adjectives. For example, the phrase ‘Mana qoricha Abbabee’ was written to say ‘Abebe drug Shop’, but the meaning is changed to ‘A house where there is a medicine that belongs to Abebe’ or ‘a house from where Abebe takes medicine’. The following are correct unlike the way they are written on billboards:

(1) Mana qorichaa Abbabee (Abebe drug shop)

(2) Mana nyaataa Abbabee (Abebe restaurant)

(3) Mana rifeensaa Abbabee (Abebe barbershop)

The sentence and phrase structure of Afan Oromo is different from sentence and phrase structure of English. Moreover, unlike in English and in Amharic, in Afan Oromo, adjectives come after the noun that they modify. For example, the adjective ‘gurracha’ (black) comes after the noun Nama (man) to modify it. So it becomes ‘Nama gurracha’ (black man). In the phrase ‘Qoricha dukkaanaa’, the structure is wrong because the writer followed the structure of Amharic in which adjectives come before the noun they modify. This is because in Amharic we say ‘Medihanit Medebbir’ (mÓ™dIhα:ni:t mÓ™dÓ™bbIr) Medihanit (mÓ™dIhα:ni:t) (Drug) and Medebbir (mÓ™dÓ™bbIr) (Store).The word ‘qoricha’ (drug) here is a noun adjective to modify the noun ‘dukkaana’ (store). Therefore, it should be written as ‘Dukkaana qorichaa’ (drug store) to give meaning; otherwise, it has no meaning as it is.

In the phrase ‘Mana foon kristaanaa’, the writer’s intention is to say ‘a house/shop where Christians can get or buy meat to eat. On the other hand, it is to say that a butcher man is a Christian, and the meat is for Christians not for Muslims. Nevertheless, as it is, it cannot convey the message that is intended. The phrase is formed from the noun mana (house) and an adjective phrase ‘foon kiristaanaa’ (Christians’ flesh).The meaning of the entire phrase is out of imagination which ‘mana foon kiristianaa’ means a house where Christians’ meat (flesh) is sold. The meaning is totally diverted to an unacceptable one because it is odd. To correct the meaning to the intended one, there should be a long /i/ sound at the end of the word ‘foon’; then it becomes ‘foonii’. Thus, the correct phrase that bears the intended meaning is ‘mana foonii kiristianaa’.

The other phrase says ‘Godina Jimaa’ which was written to say Jimma zone, but its meaning is diverted. To convey the intended meaning (message), the letter ‘m’ sound should have been made long. Since it is short now, it conveys another meaning. Thus, the word ‘Jimaa’ as it is means ‘chat’ as a result of which the meaning of the entire phrase is changed to ‘the zone in which chat is found’.

On the other hand, there is a misplaced modifier in the phrase ‘mana huccuu hodhaa’. Even though both huccuu (cloth) and hodhaa (sewing) function as adjectives in the phrase, they are disordered. The adjective hodhaa (sewing) should modify the word mana (house) by coming next to it. ‘Mana hodhaa’ means the house in which sewing activities are performed. In order to make the meaning of the phrase more clear, we need to add a noun adjective ‘huccuu’ (cloth) and it becomes ‘mana hodhaa huccuu’ (the house in which clothes are sewed).Thus, hodhaa (sewing) modifies mana (house) and huccuu (cloth) modifies hodhaa (sewing). Unlike the above, this is the correct order.

The phrase ‘Rabsaa biraa’ is also found on one of the bill boards in the town. The intention was to say ‘distributor of beer’, but the phrase does not convey the intended message because the vowel ‘a’ sound in the word ‘rabsaa’ next to letter ‘r’ and the vowel ‘i’ sound in the word ‘biraa’ were made single while they should have been made double to make the sound long. Raabsaa (distributor) and biiraa (beer) are correctly written words and when they are written together, they form meaning full phrase – Raabsaa biiraa (Distributor of beer).

Afan Oromo has five vowels, that is, sounds that can differentiate word meaning. They can be short or long. We use double vowels for long vowel sound. The length of the vowel makes a difference in word meaning for example, laga ‘river’ and laagaa ‘roof of the mouth. On the other hand, the language (Afan Oromo) has 28 consonants, that is, sounds that make a difference in word meaning (http://oromiaacademy.org/oromo-language/afaan-oromo-grammar/). We indicate consonant length by writing a consonant twice ("ss", "kk", "pp", and so forth) and its length can distinguish words from one another, for example, badaa 'bad', baddaa 'highland' (http:// en. wikipedia. org /wiki / Gemination).

However, the errors analyzed above show that most of the billboard advertisements written in Afan Oromo in the town did not consider the rule of the language. This is because; letters are misspelled in most words of the advertisements as a result of which the word meaning is changed to an unintended one. Byrne (1988), states that writing involves not only the representation of language with symbols, but also it entails correct arrangement of symbols which gives meaningful messages.

In his study, Amanuel (2012) states that most of the inscribers in the town are non-speakers of the language and also they did not take any formal training in Afan Oromo. According to him, both copy writers and the owner of the billboard intentionally want to misspell words for two reasons. First, they want to save space, second, they want to save money because money is paid for each letter. This shows that they prioritized something else than the purpose for which the advertisement is written. They did not realize the impact it has on meaning. This may be because of the lack of knowledge about length is lexically distinctive both with vowels and consonants in Afan Oromo. Moreover, they are careless about the language because of their deep-rooted negative attitude towards it.

The other serious problem observed from the analysis is related to misplacement of adjective(s) in a sentence or phrase. Unlike in both Amharic and English sentence/phrase, the position of adjective in Afan Oromo sentence or phrase is after the noun or pronoun which it modifies. Supporting this idea, Catherine (2001) described that adjective comes after noun or pronoun in Afan Oromo. Getacho (2014) also described that adjective (ibsi maqaa) come after the noun or pronoun it modifies in Afan Oromo. For example, in the phrase ‘Nama gurraacha’ (Black man), the adjective gurraacha (Black) is used after the noun Nama (man). The position of an adjective in Amharic sentence is the same with English. For example, the above phrase can be written as “ጥá‰áˆ ሰዉ” (Tikur sew) (Black man) the adjective “ጥá‰áˆ” (Tikur) (Black) is used after the noun “ሰዉ” (sew) (man). This implies that someone cannot write effective and meaning full sentence in Afan Oromo using his/her Amharic or English language knowledge unless he/she knows the language (Afan Oromo) itself well.

Nevertheless, in some of the billboard advertisements written in Afan Oromo, adjectives are used before what they are intended to modify. This shows that the writers directly translated the phrases or sentences from Amahric to Afan Oromo which is not correct because Afan Oromo has its own rule. For example in the phrase ‘Qoricha dukkaanaa’ (Table), the word ‘Qoricha’ is noun adjective and it should have been stated after the noun it modifies ‘Qoricha’. As it is, it is the direct translation from Amahric because in Amahric, we say ‘Medihanit Bet’ which is similar with ‘Drug store’ in English. The writer has no knowledge of Afan Oromo and he/she wrote this way by using his/her Amaric knowledge. The inscribers in Jimma town have no knowledge of the language (Afan Oromo) (Amanuel, 2012).

Moreover, when two or more adjectives are used together in Afan Oromo sentence, the adjectives should be ordered according to the rule of the language. When using multiple adjectives in a sequence, you must be aware of the correct adjective order (http://www.ecenglish.com/learnenglish/lessons/adjective-word-order). However, in most phrases or sentences in which double adjectives are used, in the billboards of the town, the adjectives were disordered and as a result, the sentences or phrases became meaningless. For example, in the phrase ‘Mana huccuu hodhaa’, the adjectives are disordered (Table 2).

Even though both huccuu (cloth) and hodhaa (sewing) are not basic adjectives, they function as adjectives in the phrase, and they should have been ordered correctly. The adjective hodhaa (sewing) should modify the word mana (house) by coming next to it. ‘Mana hodhaa’ means the house in which sewing activities are performed. In order to make the meaning of the phrase more clear, we need to add a noun adjective ‘huccuu’ (cloth) and it becomes ‘mana hodhaa huccuu’ (the house in which clothes are sewed).Thus, hodhaa (sewing) modifies mana (house) and huccuu (cloth) modifies hodhaa (sewing).

Generally, in Afan Oromo, we can classify adjectives in to four types based on the way they are formed or used. They are basic adjective (maqibsa bu’uuraa), nouns used as adjective (maqaalee akka maqibsaatti tajaajilan), drived adjective (maqibsa yaasaa) and compound adjective (maqibsoota digalaa) (Adugna, 2012). Each of them is explained below:

(1) Basic adjective (maqibsa bu’uuraa): It is not formed from another word. The following are the examples of basic adjectives:

Diimaa (red), gurraacha (black), adii (Wight), dheeraa (tall), gabaabaa (short), furdaa (fat), qalloo (thin), haaraa (new), magariisa (green), etc.

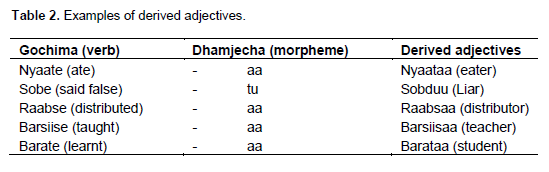

(2) Derived adjective (maqibsa yaasaa): This adjective is formed by adding morpheme (dhamjecha) on verb (gochima).So after taking the morpheme, the verb will be changed to adjective. Table 2 shows the examples of derived adjectives:

(3) Compound adjective (Maqibsa diigalaa): This type of adjective is formed from the combination of two different words. For example, the adjective ‘haraara-qabeessa’ is a compound adjective that is formed from the words ‘haraara’ (mercy) and ‘qaba’ (have).So the adjective ‘haraara-qabeessa’ means ‘merciful’ in English. The word ‘haraara’ is a noun and the word ‘qaba’) is a verb, so the compound adjective is formed from a noun and a verb.

(4) Nouns used as adjective (maqaalee akka maqibsaatti tajaajilan): For example, in the following phrases ‘Mana refeensaa’, ‘Mana nyaataa’ and ‘Mana qorichaa’, the words used after the word mana (house) are nouns. However, they are functioning as adjectives to modify the word mana (house). The vowel ‘a’ sound at the end of each of the words is made long to make the nouns function as adjectives.

Even though these are the facts about Afan Oromo adjectives, the errors on billboards in Jimma town show that the inscribers (writers) in the town lack this knowledge.

This survey, as mentioned in the introduction, was intended to analyze the errors on bill board advertisements written in Afan Oromo in Jimma town. Ninety five percent of the billboard advertisements written in Afan Oromo in the town are full of errors. However, this study focused only on the errors that totally changed the meaning of the words and phrases and affected communication. Data were collected from the bill boards in the town through observation. The collected data were analyzed using qualitative method of data analysis. Accordingly, the following are the findings of the survey:

(1) Letters are misspelled in most words of the advertisements as a result of which the word meaning is changed to an unintended one.

(2) In most phrases or sentences in which double adjectives are used, the adjectives were disordered and the sentences or phrases became meaningless.

(3) Most of the phrases or sentences were directly translated from Amahric to Afan Oromo which is not correct because Afan Oromo has its own rule.

(4) Therefore, it is possible to say that the errors are high in magnitude because of the following reasons:

(a) The existence of the errors is not stylistic (not for specific purpose)

(b) The errors changed the intended meaning to an unintended one

(c) The errors can mislead other people who do not know the language, and who perceive them as correct.

(d) The errors have negative impact on the development of the language

(1) There are two reasons for the problem to happen (Amanuel, 2012).

(a) Inscribers’ lack of knowledge on the language

(b) Inscribers’ negative attitude about the language

The errors not only affected communication but also they have a negative impact on the development of the language. Hence, the culture and tourism office of the town should do the following things to alleviate the problem:

1. Work cooperatively with the owners of the billboard advertisements erroneously written in Afan Oromo to get the advertisements rewritten correctly.

2. Teach people of the town to consult language professionals when they want to have billboard advertisements written in Afan Oromo.

3.Should not allow people who do not know the language

well (who are not professionals in the language) billboard advertisements.

4. Establish an office that supervises and checks language problems of any billboard advertisements written in Afan Oromo before they are posted.

5. Give trainings to the inscribers of the town on how to write in Afan Oromo.

6. Work cooperatively with Jimma University to mitigate the factors that affect the development of the language in the town.

Finally, the Oromia culture and tourism office in collaboration with other concerned bodies (stake holders) should strive hard to safeguard the language which is the identity of the Oromo people.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Amanuel R (2012). Linguistic landscape and language attitude: A case study on Jimma town's linguistic landscape inscribers' attitude for Afan Oromo.

|

|

|

|

Byrne D (1988). Teaching Writing Skills. Longman.

|

|

|

|

Catherine GM (2001). A Grammatical Sketch of Written Oromo. Rudier Koppe Verlag. Koln, ISBN 3-89645-039-5.

|

|

|

|

Getachew R (2011). Oromo Grammar. Addis Ababa: Kuraz international Publishing Enterprise.

|

|

|

|

Getacho R (2014). Oromo Grammar. Addis Ababa: Kuraz International Publishing Enterprise.

|

|

|

|

Getachew A, Derib A (2006). Language Policy in Ethiopia: History and Current Trends. JU Education Faculty Jimma, Ethiopia. Pam Hurley Hurley Write Inc. Wilmington NC, 14 March, 2014, Last Modified: 4/18/2014 10:00:35 AM.

|

|

|

|

Roba TM (2004). Modern Afaan Oromo grammar: Qaanqee galma Afaan Oromo. Bloomington, IN: Author house

View

|