Ethiopia is one of the sub-Saharan African countries with high maternal mortality rate due to complication of delivery. Institutional delivery care and postnatal care are key health services that can reduce maternal mortality. The main objective of this study was to identify factors affecting utilization of institutional delivery and postnatal care services. The data for this study were obtained from the 2014 EDHS which is a national representative of women aged 15-49 years. The total number of women included in the study was 3710. Descriptive analysis and binary logistic regression model were used to analyze the data. The descriptive results showed that about 26.2 and 23.6% of women used institutional delivery and postnatal care services, respectively. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the effect of each predicator variable on the use of institutional delivery and postnatal care among women. Accordingly, educational level, place of residence, sex of household head, wealth index, region and ANC visits were found to be significant determinants of utilizing both institutional delivery and postnatal care at 5% level of significance. Number of living children was also found to be a significant predictor of institutional delivery use. Women who reside in rural areas were less likely to use maternity health care services than those who live in urban areas. Education and wealth index were found to be statistically significant in the use of IDC and PNC. Thus, great attention should be given to women who are living in rural areas, in low wealth index and in illiterate group.

The WHO estimated that 536,000 women of reproductive age die each year due to pregnancy related complications worldwide. Developing countries accounted for 99% of these deaths (533,000). 51% of maternal deaths (270,000) occur in the sub-Saharan Africa regions, followed by 35% (188,000) in South Asia. Thus, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia accounted for 86% of the global maternal deaths. This showed that a high proportion of maternal deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa (WHO, 2005). In 2005, maternal mortality ratio was the highest in developing countries with 450 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. In contrast, maternal mortality ratio for developed regions was 9 deaths per 100,000 live births and in countries of the Common Wealth of Independent States, it was 51 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. Among the developing countries, sub-Saharan Africa including Ethiopia had the highest maternal mortality rates (MMR) with 900 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2005, followed by South Asia (490), Oceania (430), South-Eastern Asia (300), Western Asia (160), Northern Africa (160), Latin America and Caribbean (130), and Eastern Asia (50) (WHO, 2005). Ethiopia is one of the countries with the highest MMR in the world. The MMR was 871 per 100,000 live birth in the year 2000; it was also 673 per 100,000 live births in year 2005 and 676 per 100,000 live birth in year 2011, that is, maternal mortality ratio has not changed in the country. A study by Miteku et al. (2016) revealed that increasing awareness about postnatal care, preventing maternal and neonatal complication, and scheduling mothers based on the national postnatal care follow-up protocol would increase postnatal care service utilization.

According to the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey report, only 34, 10 and less than 9% of women had antenatal care, delivery care and postnatal care services by skilled providers, respectively (CSA, 2011). Institutional delivery and postnatal care services are the crucial issues to reduce the risk of complications and infections that can cause the death or serious illness of a mother and newborn. Despite the fact that utilization of institutional delivery care and postnatal care services are essential for further improvement of mothers and newborn health, a small proportion of babies are delivered in health facilities and majority of the women with a live birth are not checked by skilled health providers. Different studies have shown that the use of skilled delivery attendants and postnatal care services are very low in Ethiopia because of socio-economic and demographic factors. Majority of births occurred at home without the help of skilled providers and many mothers do not go for checkup after delivery. There is unbalanced distribution of using maternal health care service between regions (Kasu, 2013). Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify factors affecting utilization of institutional delivery and postnatal care services, and assess variation in the use of these services among different regions of Ethiopia.

Source of data

The source of data is the 2014 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey which is obtained from Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency designed to provide estimates for the health and demographic variables of interest for the following domains: Ethiopia as a whole, urban and rural areas of Ethiopia, and all geographical areas (nine regional states and two chartered cities), namely: Tigray, Affar, Amhara, Oromiya, Somali, Benishangul-Gumuz, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples, Gambela, Harari, Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa.

Data collection

In order to achieve the objective of the survey, a total of 9135 households aged 15 to 49 were selected, of which, 8,727 were found to be occupied during the data collection. Among the occupied households, 8492 eligible women were identified for individual interview; then interviews were completed for 8070 women yielding an individual response rate of 95%. Women were asked whether they have practiced ANC, institutional delivery and postnatal care services in the five years preceding the survey. Only 3710 of them responded and gave information on their practice of IDC, IDC and PNC (CSA, 2014).

Variables of the study

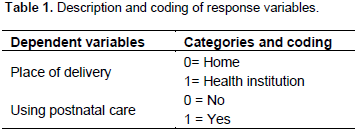

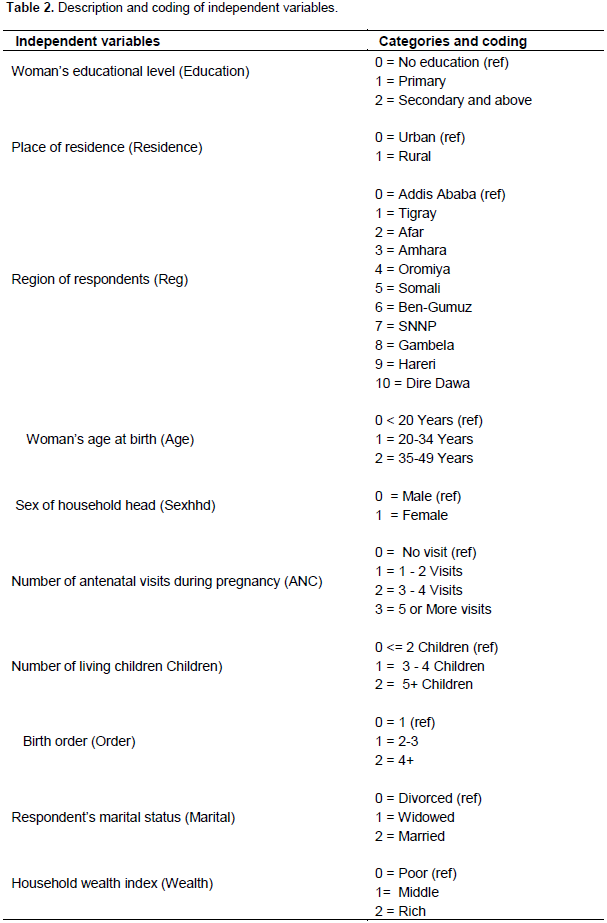

In this study, two response variables influenced by explanatory variables were obtained from questions in the maternal health component of EDHS questionnaire. The main focus was a number of specific questions that were addressed to women about their last child in the five years preceding the survey. Women were asked whether they: 1) delivered their last child from health institutions; 2) received a medical checkup within two days after delivery. As indicated in Table 1, the response variable was coded as “1” if the woman used this service and “0” if not. Explanatory variables included in the study for the purpose of the analysis were chosen by referring and reviewing related literatures. These variables are coded as indicated in Table 2 and are expected to influence the dependent variable (institutional delivery, postnatal care services) in Ethiopia.

Descriptive analysis

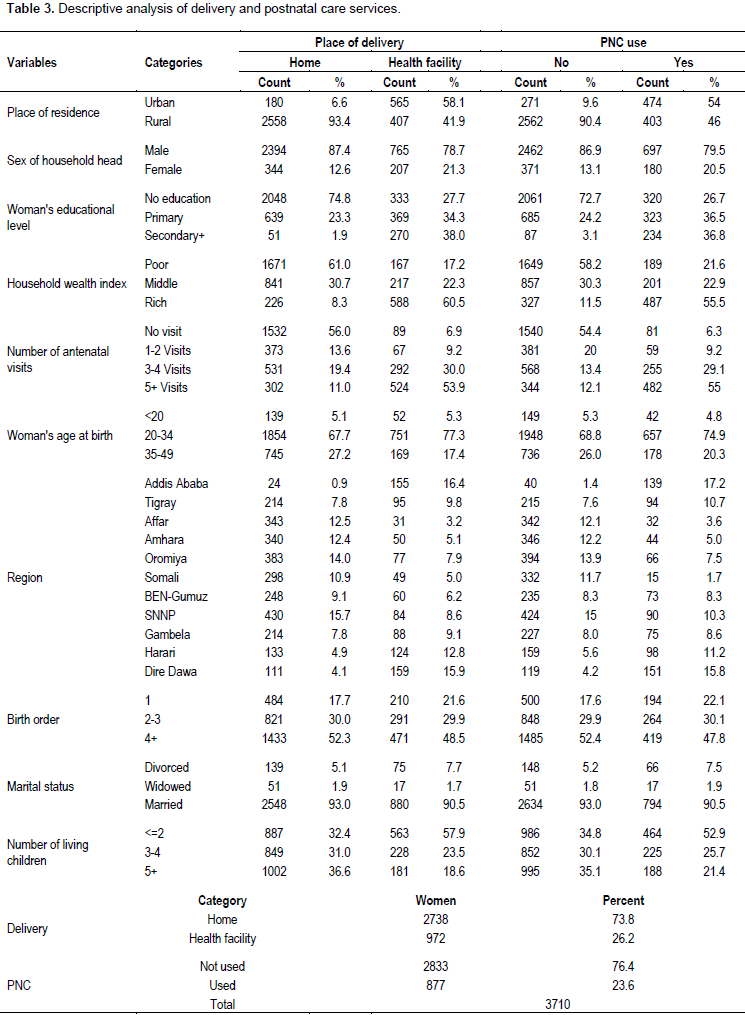

The main socio-economic and demographic factors of maternal health care service utilization of women are presented in Table 3. The total number of women included in the study is 3710. Among those, 972 (26.2%) delivered their last child at health facility while 2738 (73.8%) delivered at home. Similarly, 877 (23.6%) received postnatal care whereas 2833 (76.3%) did not. Women who lived in different states had unequal status of using institutional delivery and postnatal care services. The proportion of mothers who delivered their last child at health facilities in Affar, Amhara, Somali, Oromiya, Ben-Gumuz, SNNP, Gambela, Tigray, Hrarari, Dire Dawa and Addis Ababa are 3.2, 5.1, 5.0, 7.9, 6.2 and 8.6, 9.1, 9.8, 12.8, 15.9 and 16.4% respectively. Similarly, the proportion of mothers that received postnatal care in Affar, Amhara, Somali, Oromiya, Ben-Gumuz, SNNP, Gambela, Tigray, Hrarari, Dire Dawa and Addis Ababa are 3.6, 5, 1.7, 7.5, 8.3, 10.3, 10.7, 8.6, 11.2, 15.8 and 17.2%, respectively. The proportion of using institutional delivery and postnatal care services also differed by place of residence. Among the women who resided in urban areas, 58.1 and 54% used institutional delivery and postnatal care services, respectively, while among the rural women, 41.9% delivered at health facility and 46% received postnatal care services. Table 3 also showed that the highest distribution of using institutional delivery and postnatal care were 38 and 36.8% for women who had secondary or above education and followed by 34.3 and 36.5% for women who had primary education. Among mothers with male household head, 78.7% used institutional delivery care, while only 21.5% of mothers with female household head used this care. Similarly, mothers with male headed household (79.5%), used postnatal care service, whereas 20.5% of mothers with female headed household received postnatal care service.

Women with the higher wealth index see medical professionals for their child birth than women in lower wealth index. 60.5 and 55.5% of women whose household wealth index is rich used institutional delivery and postnatal care services. 22.3 and 22.9% of women with middle wealth index used IDC and PNC services, respectively. On the other hand, only 17.2 and 21.6% of mothers with poor wealth index used IDC and PNC, respectively. Regarding the number of children, 57.9 and 52.9% of mothers who had less than two children received IDC and PNC services, while only 18.6 and 21.4% of mothers with five or more children used IDC and PNC services, respectively. Using IDC and PNC services increase as antenatal care practice increases. Among mothers who did not follow antenatal visits, only 6.9% delivered at health facility and 6.3% received postnatal care services. Institutional delivery and postnatal care services were observed by 9.2% of women who used one or two antenatal visits. Similarly, 30 and 29.1% of women with three or four antenatal visits experienced institutional delivery and postnatal care services, respectively. 53.9 and 55% of mothers who used institutional delivery and postnatal care were observed with five or more antenatal visits. Table 3 also showed that the observed proportions of using institutional delivery and postnatal care for mothers with the first child birth were 21.6 and 22.1%, respectively. With two or three birth orders, women (29.9 and 30.1%) used institutional delivery and postnatal care services.

Bivariate analysis

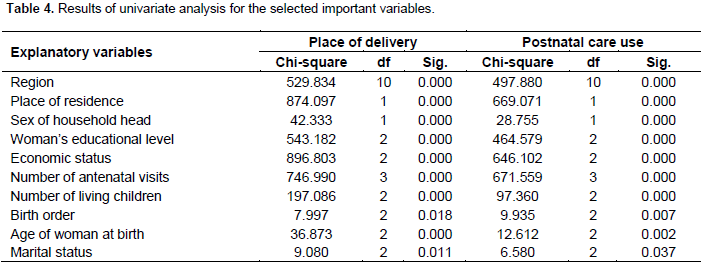

Bivariete analysis is used to describe the effect of individual explanatory variable on the outcome variables without considering other predictors. It showed the relationship between the response variable (IDC, PNC) and explanatory variables. The analysis was carried out for each predictor independently using enter method and variables were statistically significant at 5% significance level since P- value < 0.05 (Table 4). These variables are important for the multiple logistic regression analysis.

Results of binary logistic regression analysis for delivery care services

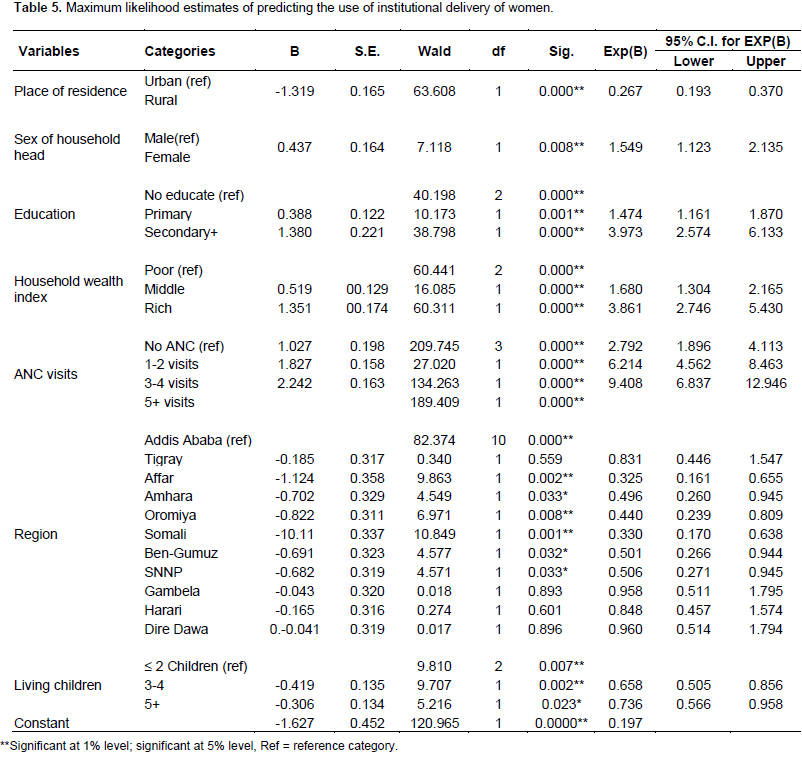

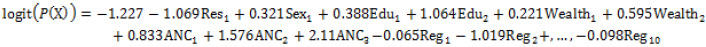

Multiple logistic regressions were applied to analyze the effect of each independent variable on institutional delivery care utilization controlling for the effect of the other independent variables. A statistical significance of the individual regression coefficients was tested using the Wald Chi-square statistic. Accordingly, region, place of residence, educational level of women, sex of household head, wealth index, and number of living children and frequency of antenatal visits were found to be significant predictors for the use of institutional delivery care services. Based on the result in Table 5, the final estimated regression equation consisting of the significant variables is given by:

When all explanatory variables are removed in the model, an average probability of using institutional delivery care service by Ethiopian women is predicted to be

= 0.164.

The logistic regression model revealed that there is a statistically significant effect between mother’s place of residence and the use of institutional delivery care services. The women who lived in rural area were 73% lower than those who delivered their last children at health facility as compared to those who live in urban area (OR=0.267; CI: 0.193-0.370) controlling for the other variables in the model. The result of the model also showed that women who are living in households where a female is the head of household were 1.549 times more likely to use institutional delivery care service as compared to women where the head of household is male. The findings of the model revealed that the odds ratio of using institutional delivery care for women who lived in Amhara and Oromia regions relative to those women living in Addis Ababa were 0.496 (CI: 0.260-0.945) and 0.440 (CI: 0.239-0. 809). Similarly, the odds ratios of using delivery care for women who lived in SNNP and Ben- Gumuze as compared to women who reside in the reference category were 0.506 (CI: 0.271-0.945) and 0.501 (CI: 0.266-0.944), respectively.

This implied that women who live in SNNP and Ben-Gumuze were about 49 and 50% lower with respect to delivering at health facilities as compared to women who live in Addis Ababa, controlling for the other variables in the model. Moreover, the likelihoods of using delivery care in health institutions for mothers who live in Somali and Affar region as compared to mothers who reside in the base category were 0.330 (CI: 0.170-0.638) and 0.325 (CI: 0.161-0.655), respectively, controlling for the other variables in the model. Meaning that women who reside in Somali and Affar are about 67 and 67.5% less likely to use institutional delivery service as compared to women who reside in the reference region, controlling for other variables in the model. This showed that majority of the women who live in Somali and Affar regions delivered their last children at home. On the other hand, the odds of using IDC for women who live in Dire Dawa, Tigray, Harari and Gambela were not significantly different from that of women who live in

Addis Ababa.

The other important significant predictor of woman’s utilization of institutional delivery care services is their educational level. Mothers with primary education were 47% more likely to use institutional delivery care relative

to those without education (OR =1.474, IC: 1.161-1.870). Similarly, the odds ratio of using institutional delivery care was 3.973 times more likely for mothers who had secondary or above education as compared to mothers who had no education, controlling for the other variables in the model. A model also explained that household wealth index has a statistically significant association with utilization of mother’s delivery care. The likelihoods of using delivery care in a health institution were 1.68 and 3.861 times more likely for women from middle and rich families, respectively, as compared to those from poor families, controlling for the other variables. Antenatal care during pregnancy has a statistically significant effect on the use of delivery care service. Women with one or two antenatal visits, three or four visits and five or above visits are 2.792, 6.214 and 9.408 times more likely to use institutional delivery care respectively, as compared to those without antenatal visit, while controlling for the other variables in the model. This indicated that women with more antenatal visits during pregnancy were better to deliver their child at health center. In the contrary, the study identified the inverse relationship between using institutional delivery care of women and their living children. The odds ratio of using delivery care in health facility was 34% less likely for women who had three or four children relative to those who had two or less children (OR = 0.658, 95% CI: 0.505-0.856).

Results of binary logistic regression analysis for PNC

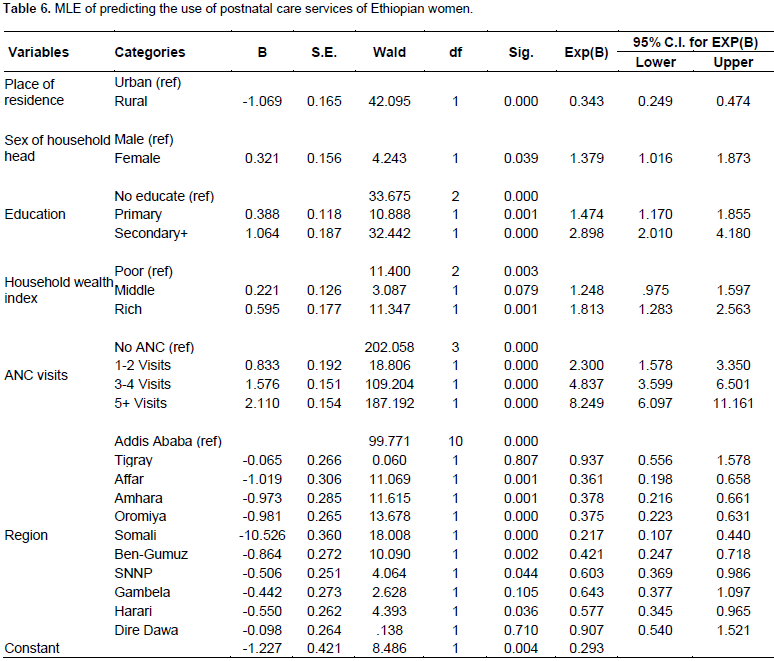

Accordingly, region, place of residence, educational level of women, sex of household head, wealth index and frequency of antenatal visits were found to be significant determinants for the use of postnatal care services at 5% level of significance. The maximum likelihood estimates (MLE) of predicting the use of postnatal care services of Ethiopian women is presented in Table 6. Based on this result, the final regression equation consisting of the significant variables is given by:

If all explanatory variables are removed in the model, an average probability of receiving postnatal care service of women from skilled providers is estimated to be = 0.227. The model revealed that there is a strong association between mother’s place of residence and the use of postnatal care services. The women who lived in rural area were about 66% lower for use of postnatal care service as compared to those who live in urban area (OR=0.343; 95% CI: 0.249-0.474), controlling for the other variables in the model. The result of the model also showed that women living in the household where a female is the head of household were 1.379 times more likely to receive postnatal care services as compared to women where the head of household is male. The model also showed that women who reside in Amhara and Oromia are 62.2 and 62.5% less likely to use postnatal care service, respectively, as compared to women who live in Addis Ababa, controlling for the other variables in the model. That is, the odds ratio of using postnatal care for women who live in Amhara and oromia as compared to women who reside in the reference category were 0.378 (CI: 0.216-0.661) and 0.375 (CI: 0.223-0.631), respectively. Similarly, the odds ratio of using postnatal care service for women who live in SNNP and Ben- Gumuze as compared to women who reside in the reference category were 0.603 (CI: 0.369-0.986) and 0.421 (CI: 0.247-0.718), respectively.

This indicated that women who live in SNNP and Ben-Gumuze were about 40 and 58% less likely to receive postnatal care services as compared to women who live in Addis Ababa, controlling for the other variables in the model. Moreover, the odds of using postnatal care for mothers who settled in Affar and Somali region as compared to mothers who live in the reference category were 0.361 (CI: 0.198-0.658) and 0.217 (CI: 0.107-0.440), respectively, controlling for the other predictors in the model. In other words, women who reside in Somali and Affar are 78 and 64% less likely to use postnatal care service as compared to women who reside in the reference region, controlling for the other variables in the model. This showed that majority of the women who live in Somali and Affar region did not receive postnatal care service. On the other hand, the odds of using postnatal care service for women who live in Dire Dawa, Tigray and Gambela were not significantly different from that of women who live in Addis Ababa. The other important significant predictor of woman’s utilization of postnatal care services is educational level. Mothers with primary education were about 47% more likely to use postnatal care service relative to those without education (OR =1.474, IC: 1.170-1.855).

Similarly, the odds ratio of using postnatal care service is 2.898 times more likely for mothers who had secondary or above education as compared to mothers who had no education, controlling for the other predictors in the model. A model also explained that household wealth index has significant positive association with utilization of mother’s postnatal care service. The likelihoods of using postnatal care service were 1.248 and 1.813 times more likely for women from middle and rich families, respectively as compared to those from poor families. Antenatal care during pregnancy had also a positive association with the use of maternal postnatal care service. Women with one or two antenatal visits, three or four visits and five or above visits were 2.3, 4.837 and 8.249 times more likely to receive postnatal care, respectively, as compared to those without antenatal visit while controlling for the other variables in the model. This indicated that more antenatal visit during pregnancy to checkup after delivery is better for mothers.

Testing goodness of fit of the model

After logistic regression model has been fitted, goodness of fit test of the resulting model was performed. It is necessary to show the adequacy and usefulness of the fitted model. The most common techniques are Pearson's Chi-square test, likelihood ratio test, Hosmer- Lemeshow test and the Wald goodness of fit test.

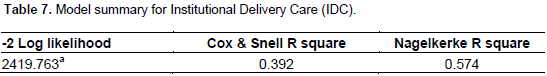

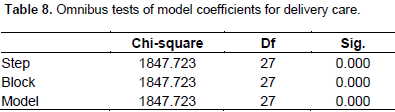

The Omnibus or likelihood-ratio test (LRT) for delivery care

LRT is the common assessment of the overall model fit in logistic regression, which is simply the Chi-square difference between the reduced model with the constant only and the full model including a set of predictors. As indicated in Table 7, the -2 log likelihood statistics is 2419.763. This statistic shows how much improvement is needed before the predictors provide the best possible prediction of IDC, the smaller value of statistic is the better of the model. The statistic for the model (Table 8) with only the intercept is given by -2LL0 = 1847.723+2419.763 = 4267.486. The model with predictors reduced the -2 Log Likelihood statistics (null model) by 4267.486– 2419.763 = 1847.723, which is observed in the model Chi-square for omnibus test. The omnibus test can be interpreted as a test of the ability of all explanatory variables in the model jointly to predict the response variable. The omnibus test of model coefficients is used to assess the overall fit of logistic regression model. The results (

=1847.723, d.f=27, p-value = 0.000) in Table 8 showed that the model fit is good, at least one of the predictors is statistically significant to predict the use of institutional delivery services. Deleting independent variables from the model change its predictive ability or the null hypothesis that there is no difference between the model with only a constant and the model with predictors was rejected.

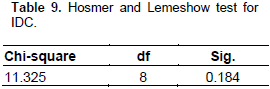

Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test for delivery care service

The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test divides subjects into ten groups based on predicted probabilities, then a Chi-square is computed from observed and expected frequencies in a 10x2 table. A non-significant value of a Chi-square test indicated that there is no difference between the observed and the predicted values and hence the estimated model goodly fit the data. Since the p-value = 0.184 is greater than 0.05, it is not significant, which is an indication that the overall fitted model is good (Table 9).

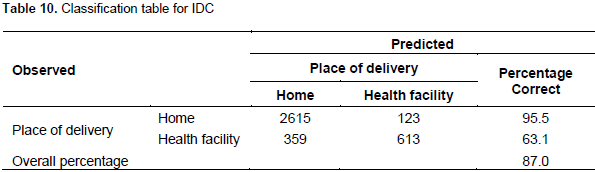

The classification table for IDC

The classification table showed the validity of predicted probabilities. The accuracy of the classification is measured by sensitivity (ability to predict an event correctly) and specificity (ability to predict the non-occurrence of an event correctly). Table 10 shows that 63.1% of women who delivered at health center were correctly classified, whereas 95.5% of women that delivered at home were correctly classified.

Model diagnostics for IDC and PNC

The adequacy of the fitted model was checked for possible presence of outliers and influential values. Results of the diagnostic test for detection of outliers and influential values are presented in Appendix 1 (Tables 1 and 2). The DFBETA for model parameters is small (all values are less than one). This means that there are no influential observations for the individual regression coefficients. Cook’s distance less than one implied that an observation had no overall impact on the estimated vector of regression coefficients β. A small value of leverage statistic showed that no subject has a substantial large impact on the predicted values of the model. Another method of detecting outliers is normalized residuals. The absolute value of normalized residual is less than 3. This indicated the absence of outlying observation (Appendix 1: Table 1). Hence, from the above goodness of fit test and diagnostic checking, it can be said that our model is adequate to predict the data.

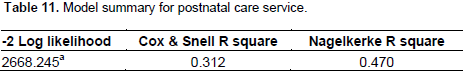

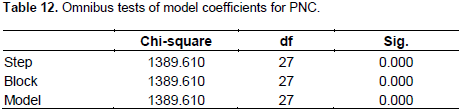

The omnibus or likelihood-ratio test for postnatal care

On Table 11, it was considered that the -2 log likelihood statistics equals 2668.245. This statistic shows how much improvement is needed before the predictors provide the best possible prediction for the use of postnatal care of women. The statistic for the null model is given by -2LL0 = 1389.610+2668.245=4057.855. The inclusion of parameters reduced the -2 Log Likelihood statistics of null model by 4057.855–2668.245 = 1389.610, which is observed in the model Chi-square of omnibus test. The results, Chi-square = 1389.610, df = 27, p-value=0.000 showed that the model fit is good, that is, at least one of the predictors is statistically significant to predict the use of postnatal care service (Table 12). This is the null hypothesis that there is no difference between the model with only a constant and the model with predictors was rejected.

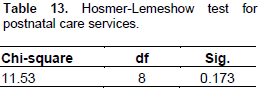

Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test for PNC

The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test divides subjects into ten groups based on predicted probabilities, then a Chi-square is computed from observed and expected frequencies in a 10x2 table. A non-significant Chi-square indicated that there is no difference between the observed and the predicted values and hence estimates of the model adequately fit the data. Since the p-value 0.173 in Table 13 is greater than 0.05, the model is good fit to the data.

The classification table for PNC

A classification table shows the validity of predicted probabilities. The accuracy of the classification is measured by sensitivity (ability to predict an event correctly) and specificity (ability to predict the non-occurrence of an event correctly). Table 14 shows that 54.4% of women who received postnatal care were correctly classified, whereas 94.7% who did not receive postnatal care were correctly classified.

Model diagnostics for PNC

The adequacy of the fitted model was checked for possible presence of outliers and influential values. Results of the diagnostic test for detection of outliers and influential values are presented in Appendix 1 (Table 2). The DFBETA for model parameters is small (all values are less than one). This means that there are no influential observations for the individual regression coefficients. Cook’s distance less than one implied that an observation had no overall impact on the estimated vector of regression coefficients β. A small value of leverage statistic showed that no subject has a substantial large impact on the predicted values of the model. Another method of detecting outliers is normalized residuals. The absolute value of normalized residual is less than 3. This indicated the absence of outlying observation (Appendix 1: Table 2). Hence, from the above goodness of fit test and diagnostic checking, it can be said that our model is adequate to predict the data.

Test of heterogeneity

A Chi-square test statistic was applied to assess heterogeneity in the proportion of women who had an experience of maternal health care services between regions. The test yield Chi-square = 529.834 for place of delivery and 497.880 for postnatal care, df =10, P- value <0.05. Thus, there was an evidence of heterogeneity with respect to using institutional delivery and postnatal care services across regions.

A total of 3710 women were included in the study to investigate determinant factors influencing utilization of institutional delivery and postnatal care services. The descriptive analysis of this study showed that 26.2 and 23.6% of women use institutional delivery and postnatal care services, respectively. The study identified major socio-economic and demographic factors of institutional delivery and postnatal care services in Ethiopia. The study revealed that place of residence, women’s educational level, region, wealth index of the household, number of antenatal visits during pregnancy and sex of household head were significant factors for both institutional delivery use and postnatal care services. Number of living children is also a significant predictor of using institutional delivery service, while age, marital status and birth order were found to be insignificant variables of utilizing institutional delivery and postnatal care services. The study showed that utilization of institutional delivery care service was significantly associated with place of residence. Women who resided in rural areas and with lower wealth index were at less advantage to deliver in health facilities and receive postnatal care. This is in agreement with the findings of others studies (Mesfin et al., 2004; Eyerusalem, 2010; Asmeret, 2013). The finding also showed that place of residence was statistically a significant predictor for the use of postnatal care service. Rural women are less likely to use postnatal care service relative to urban women. This confirmed the finding of the other studies (Mitiku et al., 2016; Mekonen, 2002; Asma, 2013). The reason for this difference is unfair distribution of health care services; most of the health care services are concentrated in urban areas than rural and various health promotion programs that use urban-focused mass media leads to the advantage of urban residents to use maternal health service. In addition, women living in rural residence are more influenced by traditional or cultural practice regarding delivery and postnatal than urban women.

The finding revealed that mother’s education has a strong positive association with the use of institutional delivery and postnatal care services. Women with primary, secondary or higher level of education were more likely to deliver at health facility and receive postnatal care than women who had no education. This finding, in agreement with Mekonnen and Mekonnen (2002), Umurungi (2010) and Abeje et al. (2014), revealed that the lower use of maternal health care was observed among illiterate women. The reason might be that a higher education can enable women to develop the confidence of utilizing health facility services and greater awareness of the need for their care during delivery and after delivery. Wealth index of the household is one of the most positive determinants of using institutional delivery and postnatal services among Ethiopian women. According to the current study, giving birth at health facility as well as receiving postnatal services were higher for women in middle and rich households as compared to women living in lower economic status. This finding is consistent with other studies carried out by Fort et al. (2011) and showed that women with middle and rich households were more likely to utilize delivery and postnatal services in health center. Similar studies (Adamu, 2011; Kasu, 2013) revealed that household wealth index was a significant predictor for women to deliver at health facilities and to use postnatal care. As recommended by WHO, at least, four ANC visits are important for maternal health.

The results of this study showed a significant difference in the proportion of health facility delivery among women who followed one or more ANC visits as compared to women who had no ANC visits. This confirmed the findings of other studies (Mesfin et al., 2004; Asmeret, 2013) showing that women with ANC visits were more likely to deliver at health facility as compared to those without ANC visits. The study also showed a positive association of ANC visits during pregnancy with mother’s utilization of postnatal care service, which is consistent with the findings of the other studies (Asma et al., 2013; Daniel et al., 2014), that following the higher antenatal care increases the use of postnatal care services. Sex of household head is also statistically a significant predictor for utilization of institutional delivery and postnatal services among women. The finding showed that women who live in female headed households were more likely to deliver at health facility and receive postnatal care services as compared to those who live in male headed households. This result is in agreement with Kasu (2012), which showed that the estimated odds ratio of mothers who live in house where the head of household is female were more likely to receive delivery and postnatal care from a health facilities as compared to women who live in household where the head is male.