ABSTRACT

There is insufficient evidence documenting and comparing the prevalence and covariates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk behaviours among circumcised and uncircumcised men in Botswana. The main aim of this paper was to assess prevalence and covariates of HIV risk behaviours among circumcised and uncircumcised men in Botswana. Data used for this study was derived from the 2013 Botswana AIDS Impact Survey which was a nationally representative, population-based survey. Cross-tabulations and logistic regression analysis were used to assess covariates of HIV risk behaviours among circumcised and uncircumcised men. Mean age for participants in the study was 30.46 years. From a total sample of 3809 men, only 25% were circumcised, 90% had ever heard about safe male circumcision program, 9% were of the view that circumcised men should stop using condoms. Results show that 67% of men were circumcised in government health facility, 16% in private health facility, while 17% in a traditional setting. Logistic regression results show evidence of risk compensation (multiple sex partners) among circumcised men (OR=1.027; 95% CI: 1.002-1.053). On the other hand, circumcised men were less likely to have not used condoms consistently (OR=0.672; 95% CI: 0.531-0.753). Alcohol consumption was found to be a statistically significant covariate of having multiple sex partners (OR=2.101; 95% CI: 2.044-2.161) while in rural residence, Christianity, primary education and the belief that circumcised men should stop using condoms were associated with inconsistent condom use. Further research is needed to understand the complex relationship between men’s circumcision status and HIV risk behaviours in order to design effective interventions.

Key words: Determinants, circumcised, un-circumcised, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk behaviour, Botswana.

In 2009, the government of Botswana adopted safe male circumcision (SMC) as one of the possible strategies to prevent and reduce transmission of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). This came about because Botswana is among the top three countries in sub-Saharan Africa which have been highly affected by HIV/AIDS epidemic. Recently, HIV/AIDS and related sicknesses have been the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in Botswana. Meanwhile, the introduction of antiretroviral has led to substantial declines in HIV/AIDS related morbidity and mortality (Keetile and Rakgoasi, 2014). In 2004, the Botswana AIDS Impact Survey II (BAIS II) estimated a national HIV/AIDS prevalence rate of 17.1%, in 2008 BAIS III prevalence rate was estimated at 17.6% (Statistic Botswana, 2009), while in the latest BAIS IV (2013), the national HIV/AIDS prevalence rate was estimated at 18.5% in the general population, and at 15.6% among men (NACA, 2014).

Safe male circumcision in Botswana was introduced as a national response to HIV/AIDS epidemic and it serves to augment existing series of response plans adopted by the government of Botswana over the years. Some initial studies on safe male circumcision have identified SMC as an effective strategy to reduce HIV infection among hetero sexual men (Bailey, 2002; Largarde et al., 2003; Gray et al., 2007). These initial studies from Kenya, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, South Africa, and also in Botswana, have evidently indicated that in settings where HIV prevalence is high there are also high levels of acceptability of SMC (Nnko et al., 2001; Bailey, 2002; Largarde et al., 2003; Kebaabetswe et al., 2003; Mattson et al., 2005).

Further, the three randomized clinical trials have shown that men who are circumcised are less than half as likely to become infected with HIV within the trial periods (Bailey et al., 2002; Lagarde et al., 2003; Gray et al., 2007). A randomized controlled trial conducted among uncircumcised men aged 18 to 24 years in South Africa in 2005, showed that male circumcision reduced the risk of acquiring HIV by 60% (Auvert et al., 2005). Moreover, two more studies conducted in Uganda (Gray et al., 2012) and Kenya (Westcamp et al., 2017) showed similar results. Models based on data from the clinical trials have predicted that routine male circumcision across sub-Saharan Africa could prevent up to six million new HIV infections and three million deaths in the next two decades (Mattson et al., 2005; Agot et al., 2007; Bailey et al., 2002).

There is evidence on the efficacy of safe male circumcision in reducing risk of HIV infection among heterosexual men which has resulted in increased demand for male circumcision services in many African countries (Letamo, 2011; Shi et al., 2017).

In Botswana, available evidence indicates that the proportion of circumcised men stood at 11% in 2008 and it had increased to 25.4% in 2013 (NACA, 2014). BAIS IV results indicate that younger men showed lower circumcision rates than their older counterparts. About 23% of young men in the 15-19 and 20-24 year categories were circumcised compared to 27, 31 and 39%, respectively, among those in the 30-34 and 35-39 and 55-59 years groups (NACA, 2014). There is need to re-assess the current prevalence and covariates of HIV risk behaviors among circumcised and uncircumcised men in Botswana. Previous study using data derived from BAIS III survey of 2008 indicated that being circumcised, or expressing willingness to be circumcised, was associated with significant increase in the likelihood of having two or more current sexual partners, and having had sex with multiple partners during the year leading to the survey (Keetile and Rakgoasi, 2014).

Further, a study by Ayiga and Letamo (2011) found that 15% of circumcised men did not use condoms compared to 12% of uncircumcised men, and circumcision was not significantly associated with condom use and also that non-use of condoms was significantly affected by religious beliefs, low level of education, marriage, drunkenness, and misconceptions regarding antiretroviral therapy.

Although, the two mentioned studies were on SMC and HIV risk behaviours, none has specifically made a comparative analysis of the prevalence of HIV risk behaviours among circumcised and uncircumcised men in Botswana and both used BAIS III data, hence, there could have been changes in HIV risk behaviours during the inter survey period. This paper, therefore, uses a comparative approach to assess extensively the prevalence and covariates of HIV risk behaviours among circumcised and uncircumcised men in Botswana using the latest BAIS data.

Data sources

Data used in this paper is from the 2013 Botswana AIDS Impact Survey (BAIS-IV), which is the fourth and latest among a series of nationally representative demographic surveys aimed at providing up to date information on the Botswana’s HIV/AIDS pandemic. Some of the objectives of the BAIS IV included providing latest information on the national HIV prevalence and incidence estimates among the population 18 months and above; to provide indicative trends in sexual and preventive behavior among the population aged 10-64 years; and provide a comparison between HIV rate, behavior, knowledge, attitude, poverty and cultural factors that are associated with the pandemic with estimates derived from previous surveys.

Stratification

All districts and major urban centres became their own strata. Enumeration Areas (EAs) were grouped according to ecological zones in rural districts and according to income categories in cities/towns.

Geographical stratification along ecological zones and income categories was undertaken to improve the accuracy of the survey data because of the homogeneity of the variables within each stratum.

Sampling design

BAIS-IV employed a national two stage sample survey design. The first stage was the selection of Enumeration Areas (EAs) as Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) selected with probability proportional to measures of size (PPS), where measures of size (MOS) were the number of households in the EA as defined by the 2011 Population and Housing Census.

EAs were selected with probability proportional to size. In the second stage of sampling, the households were systematically selected from a fresh list of occupied households prepared at the beginning of the survey's fieldwork (that is, listing of households for the selected EAs) and households were drawn systematically. Data collection was done using smart phone tablets instead of the conventional paper based method. Estimates for response rates showed that 83.9% of persons aged 10 to 64 answered individual questions. The targeted sampled population (aged 10-64 years) for BAIS IV was 9,807 and from this, 8,321 individuals were successfully interviewed yielding a response rate of 83.9% (NACA, 2014).

Study sample

From a total of 8,321 individuals who were successfully interviewed during BAIS IV, a sample of 3809 males aged between 10 and 64 years who had successfully completed BAIS IV individual questionnaire was selected using SPSS data selection command and included for analysis.

Measurement of variables

Dependent variables

The main outcome variable for this paper is HIV risk Behaviour, measured by two related variables.

Multiple sexual partners: This was derived from a question which sought to find out the number of sexual partners a respondent had in the past 12 months preceding the survey.

Based on this question, respondents were requested to list the number of sexual partners they had, the responses ranged from 0 partner to many partners (denoted by the highest number of partners listed).

The variable was coded such that respondents who had 0 to 1 partner meant they had safe sexual behaviour in the past 12 months, while more than 1 partners meant multiple sexual partners, hence HIV risk behaviour. The outcome variable was coded such that, multiple sex partners yes=1 and no=0.

Inconsistent condom use: Inconsistent condom use was measured by responses to questions that sought to find out if the respondents had always used condoms with three different sexual partners.

A composite variable for condom use inconsistency with past three sexual partners was then derived from the three questions, which are as follows: did you always use condoms with most recent partner in the past 12 months (possible responses, yes=1 and no=2); did you always use condoms with next most recent partner in past 12 months (possible responses, yes=1 and no=2), and did you always use condoms with second most recent partner in past 12 months (possible responses, yes=1 and no=2)?

All the ‘no’ responses for an individual were summed up to indicate level of condom use inconsistency, while all ‘yes’ responses were summed up to denote consistent condom use. Inconsistent condom use therefore means that the respondent did not use condom consistently with their partner(s) in the past 12 months.The resultant variable was coded such that inconsistent condom use, yes=1 and no=0.

Explanatory variables

This paper assesses the effect of the following variables on men’s HIV risk behaviour.

Male circumcision: Male circumcision was used as the key independent variable for HIV risk behaviour among men. This variable was gotten from the question, “Are you circumcised”. Responses to this question were yes, no and don’t know and the ‘don’t know’ response was filtered out to remain with yes =1 and no = 2.

Control variables

Variables such as age, education, marital status, religion, and place of residence were used as control variables. Previous studies have used these variables as control variables (Rosenberg et al., 1999; Mah and Halperin, 2010) because conceptually these variables are likely to have an association with men’s sexual and HIV risk behaviours. In order to hold constant their likely association with men’s HIV risk behaviours, these variables were included in the regression models, so that the association between independent variables becomes isolated and clear.

Furthermore, the following behavioural variables have been used as extraneous variables which may influence the effect of male circumcision on HIV risk behaviours.

HIV status: The following question was used “What were the results of your test?” This was a follow-up question to the question “Have you ever been tested for HIV, the virus that causes AIDS? This question on HIV results was asked of men who said yes they have been tested for HIV. Possible responses were HIV Negative=1, HIV Positive=2. The ‘don’t want to tell’ and ‘don’t know’ responses were dummy coded to derive a ‘don’t know and don’t want to tell category=3’.

Do you think circumcised men should stop using condoms: This question was used to assess whether circumcised and uncircumcised men who thought that circumcised men should stop using condoms had HIV risk behaviour. Possible responses to this question were yes=1 and no= 2.

Alcohol consumption: This variable was derived from item asking respondents whether they have been taking alcohol in the past 12 months. The codes were such that yes=1 and no=2.

Information about circumcision: This was derived from the question asking men whether they have seen information about safe male circumcision in the last four weeks? Responses were coded such that yes=1 and no=2.

Statistical analysis

Bivariate and multivariate data analysis techniques were employed to assess the influence of independent variables on the dependent variables. Results for bivariate analysis were presented as percentages. Pearson c2 tests were used for testing the association between circumcision status, socio-demographic and behavioural variables, at p<0.05. Binary logistic regression results were presented as Odds Ratios (OR) together with their 95% confidence intervals. Two logistic regression models were run to predict the association between male circumcision and HIV risk behaviours. Model 1 presents the probability of HIV risk behaviour among men while controlling for socio-demographic characteristics of respondents. Model 2 introduces behavioural variables to assess the probability of HIV risk behaviour among men while controlling for background and behavioural variables. The model includes male circumcision status, background, and behavioural variables. Data analysis was done using SPSS version 22 program. Complex samples modules in SPSS was used to control for cluster effects since the data analysed was collected using stratified cluster sampling.

Study sample

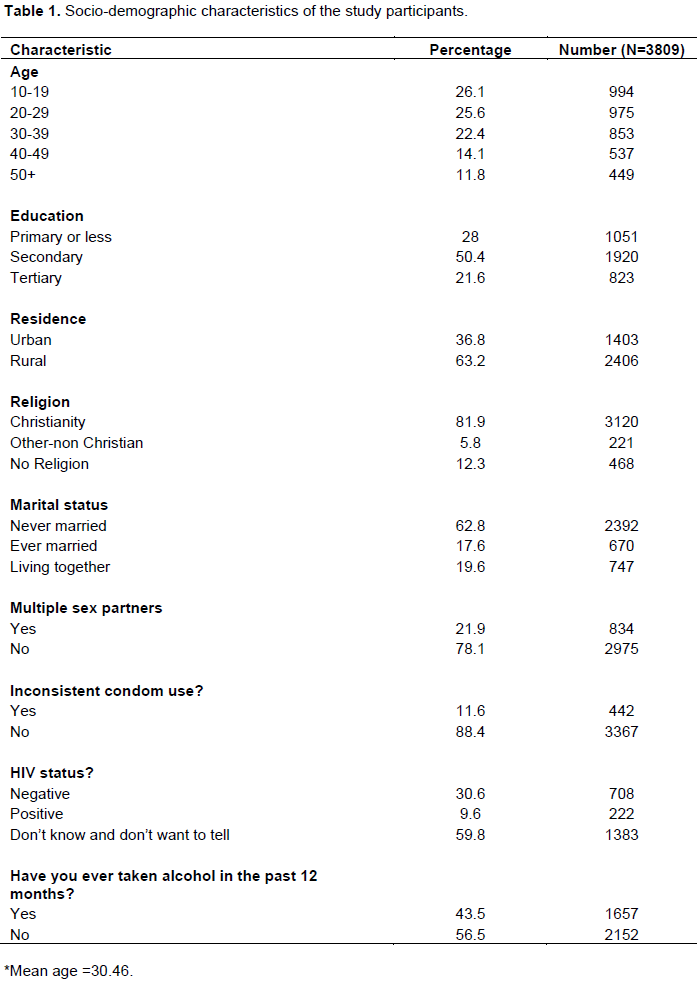

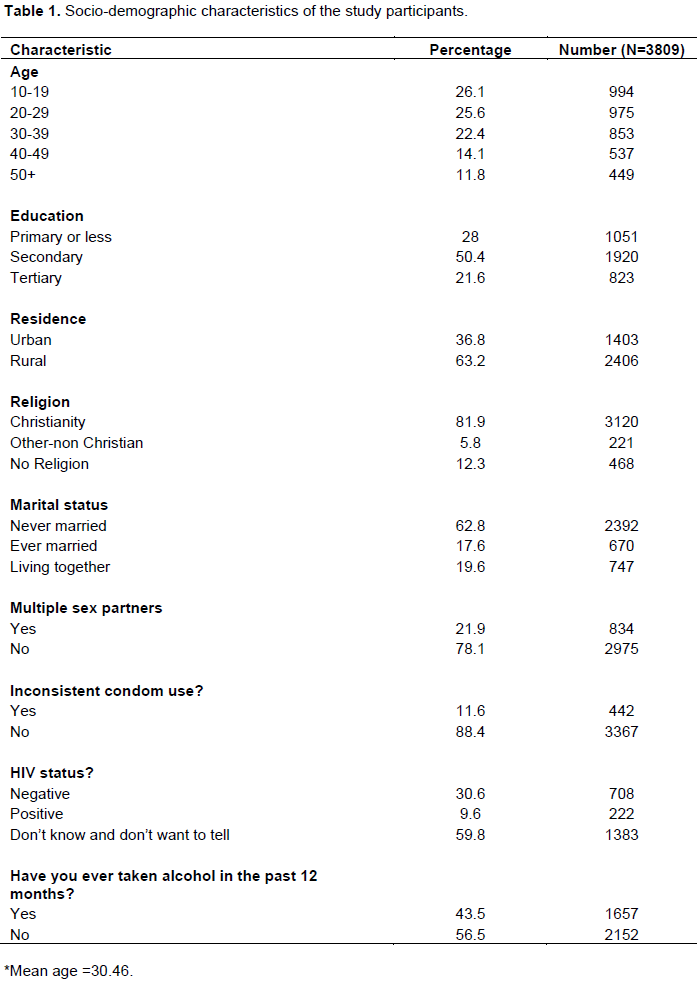

From a total sample of 3809 men aged 10 to 64 years, only 25% (960) of men were circumcised. Mean age for men who participated in the study was 30.7 years. Table 1 results show that men in ages 10-39 years represented about three quarter (74%) of the study participants, while respondents in ages 40-64 years accounted for about one quarter (26%) of the sample. Half (50%) of men in the sample had secondary education, more than one quarter (28%) had primary education while about one fifth (21%) had tertiary education. Men in the sample were predominantly from rural areas, accounting for 63%. Meanwhile, 82% of men were reported to be of Christian religion, 12% no religion, while the remaining 6% were from other non-Christian religions. More than one fifth (22%) have had multiple sex partners in the past 12 months prior to the study, while 12% reported inconsistent condom use in the past 12 months. A large percentage (96%) of men had once tested for HIV/AIDS, while more than two fifths (44%) of men reported to have taken alcohol in the past twelve months.

Prevalence of HIV risk behaviours among men by circumcision status, socio-demographic and behavioural variables

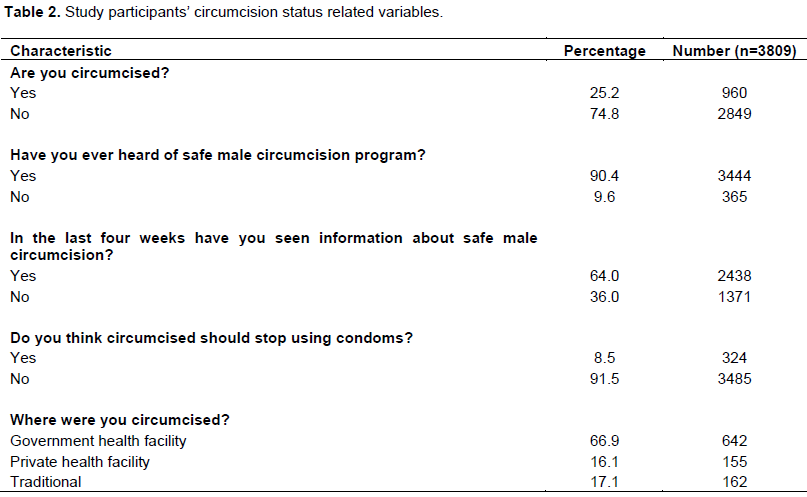

Table 2 show variables relating to male circumcision. Results indicate that about one quarter (25%) of respondents was circumcised. More than 90% of men in the study had ever heard about the safe male circumcision program, while 64% of men had seen information about safe male circumcision in the last four weeks prior to the survey.

About 9% of men in the sample were of the view that circumcised men should stop using condoms. Among circumcised men 67% were circumcised in a health facility, 16% in a private health facility and 17% were circumcised in a traditional setting.

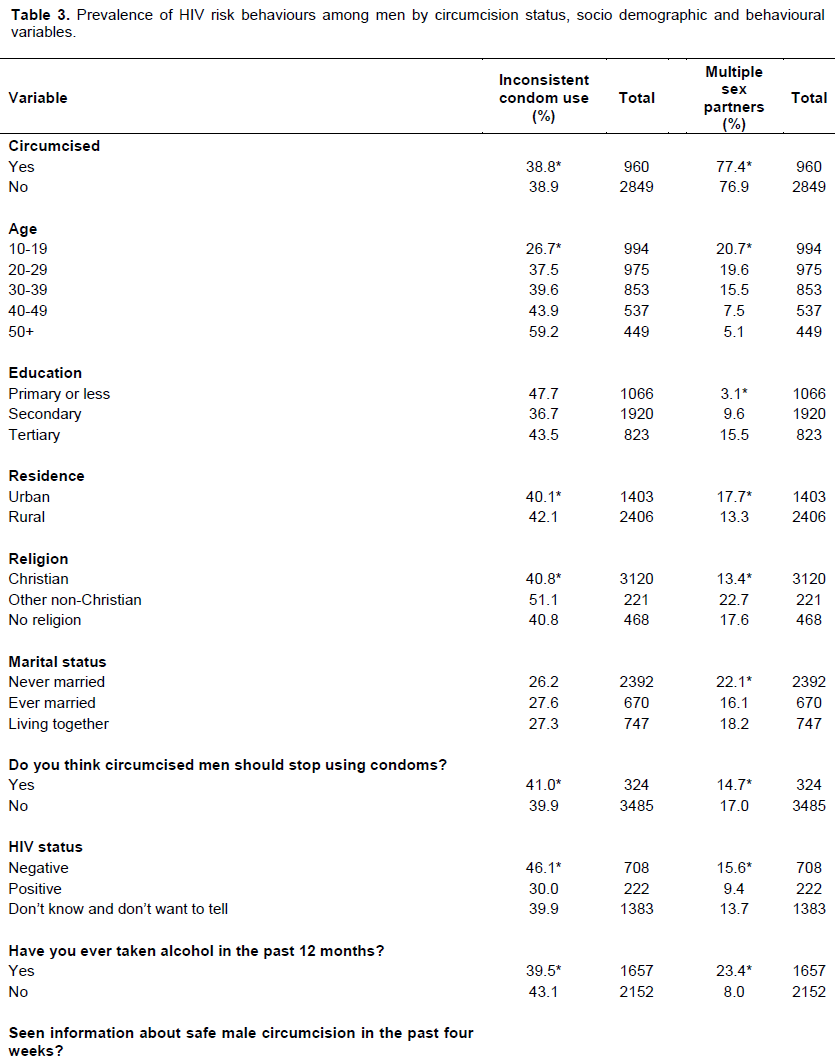

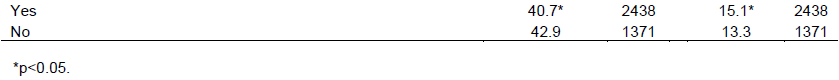

Table 3 results show statistically significant association between circumcision status and inconsistent condom use. About 39% of both circumcised and uncircumcised men reported inconsistent condom use with the past three sexual partners.

As age increases the proportion of men (both circumcised and uncircumcised) who reported inconsistent condom use also increased. Inconsistent condom use was significantly high among circumcised men with primary or less education (53%) compared to men in other education groups and it was also significantly high in rural areas (42%) than men in urban areas (40%).

Results show that 41% of men who were of the view that circumcised men should stop using condoms did not use condoms consistently, while 46% among HIV negative men did not use condoms consistently compared to 30% among HIV positive men.

A slightly high proportion among circumcised men (77.4%) than uncircumcised men (76.9%) reported multiple sex partners. Meanwhile as age increases the proportion of men reporting multiple sex partners among age groups declined for circumcised men. For example men in ages 10 to 19 years (21%) reported multiple sex partners than men in ages 50+ years (5%).

Furthermore results indicate that circumcised men with tertiary education (19%) had multiple sex partners than men of other education groups, while 18% among men in urban areas compared to 13% among men in rural areas also reported multiple sex partners. The proportion of men who were of the view that circumcised men should stop using condoms (15%) was lower than for the men who thought otherwise (17%). Multiple sex partners were also high among HIV negative men (16%) than HIV positive men (9%), while among men who had taken alcohol in the last 12 months (23%) reported to have had multiple sex partners.

Covariates of HIV risk behaviours among circumcised and uncircumcised men

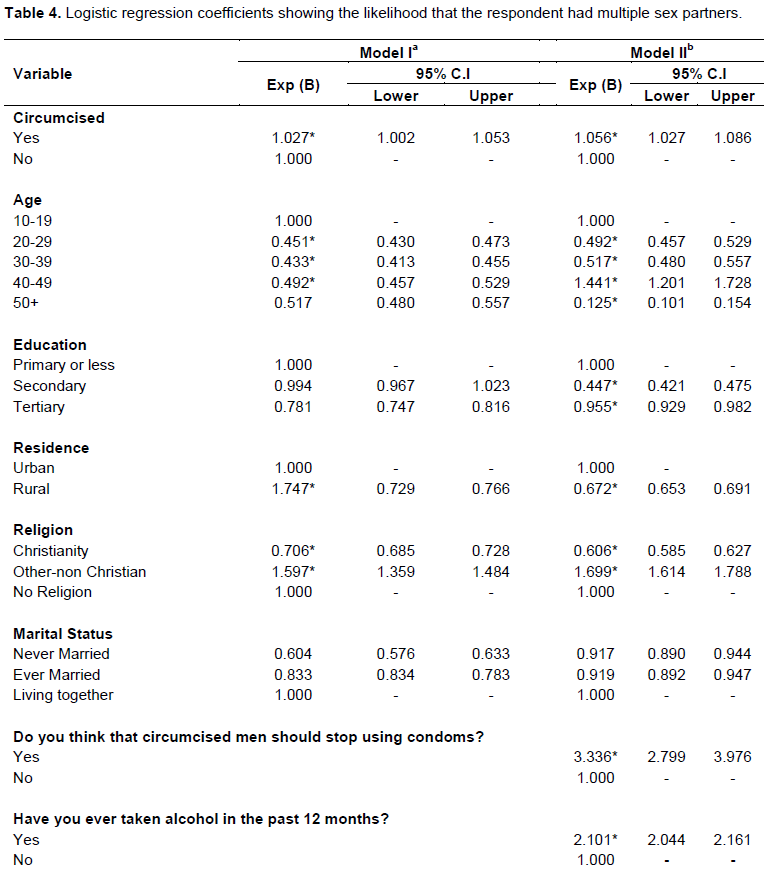

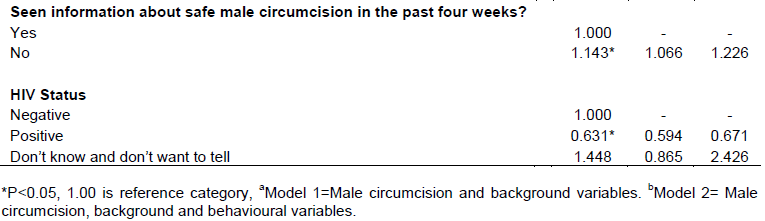

This part of the article presents results on the association between male circumcision and HIV risk behaviours, mainly multiple sex partners and inconsistent condom use using logistic regression models. The results show the odds ratios for the effect of male circumcision on HIV risk behaviours. For each HIV risk behaviour, there were two models run; Model 1and Model 2

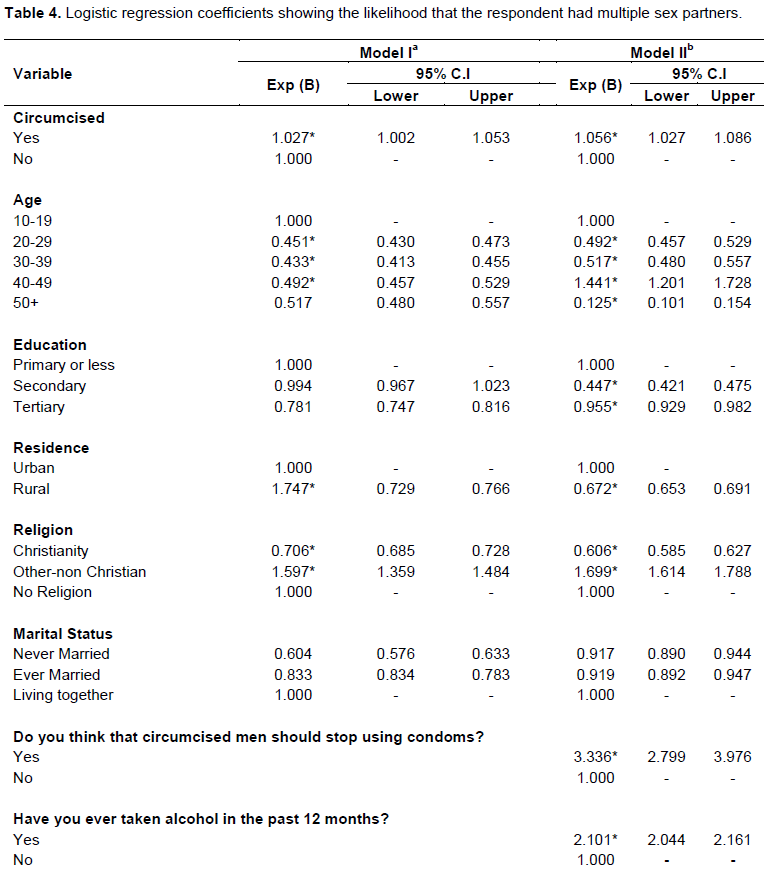

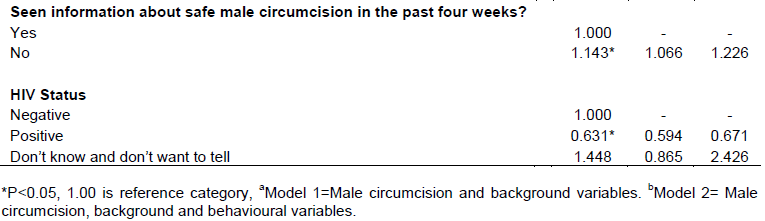

Male circumcision and multiple sex partners

Table 4 shows logistic regression odds ratios of the association between male circumcision and having multiple sex partners. Bivariate results (Table 3) have shown significant association between circumcision status and HIV risk behaviours. Furthermore, logistic regression results also show statistically significant association between socio-demographic, behavioural variables and HIV risk behaviours. Controlling for background variables (in Model I) circumcised men were more likely (OR=1.027; CI: 1.002-1.053) to have multiple sex partners compared to uncircumcised men. Meanwhile, socio-demographic variables such as age, education, residence, and religion were found to be significantly associated with having multiple sex partners. Results show that as age increases the odds of multiple sex partners decline. Men of other-non Christian religious affiliation were more than 1.5 times (OR=1.597; CI: 1.359-1.484) more likely to have multiple sex partners than men with no religious affiliation. Meanwhile Christian men were less likely (OR=0.706; CI: 0.685-0.728) to have multiple sex partners compared to men with no religion.

Model II introduces behavioural variables which may have an effect on the association between male circumcision and having multiple sex partners. Results indicate that even after introducing behavioural variables, the positive association between male circumcision and multiple sex partners is still maintained. Circumcised men were observed to be more likely (OR=1.056; CI: 1.027-1.086) to report multiple sex partner than uncircumcised men. Even after introducing behavioural variables, socio-demographic variables such as age, education, residence, religion and marital status maintained their significant association with multiple sex partners.

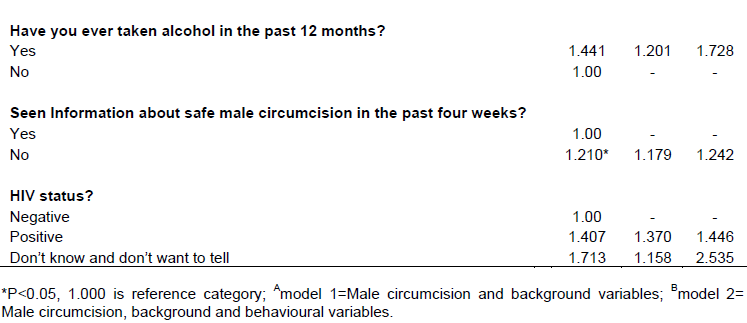

No statistical association was found between having multiple sex partners, marital status, and the view that circumcised men should stop using condoms. Results however, indicate significant association between having multiple sex partners and alcohol consumption, information about safe male circumcision and HIV status. For instance men who consume alcohol were 2 times (OR=2.101; CI: 2.044-2.161) more likely to report multiple sex partners than men who do not consume alcohol, while men who did not see any information about safe male circumcision in the past four weeks were also more likely (OR=1.143; CI: 1.066-1.226) to have multiple sex partners compared to those who had seen information. HIV positive men were less likely (OR=0.631; CI: 0.594-0.671) to have multiple sex partners compared to HIV negative men.

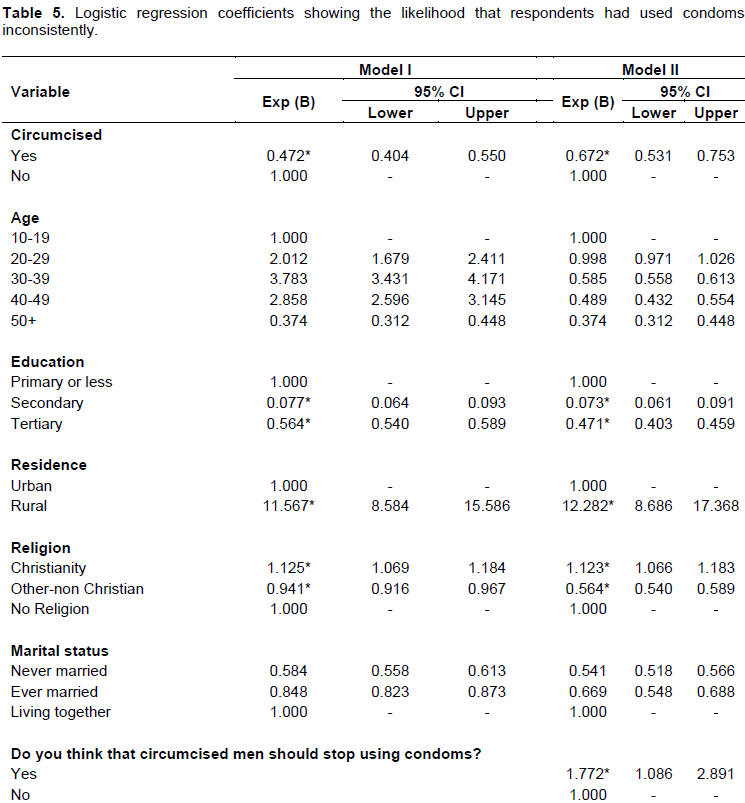

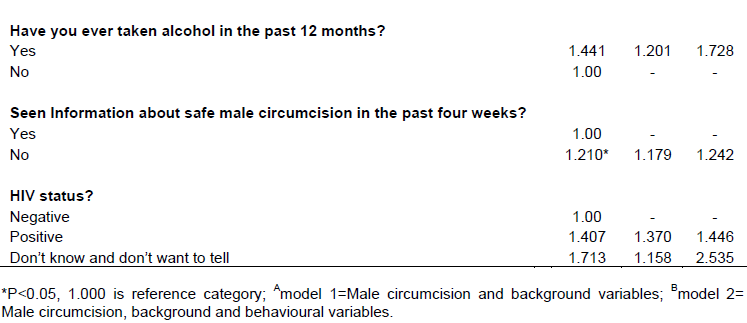

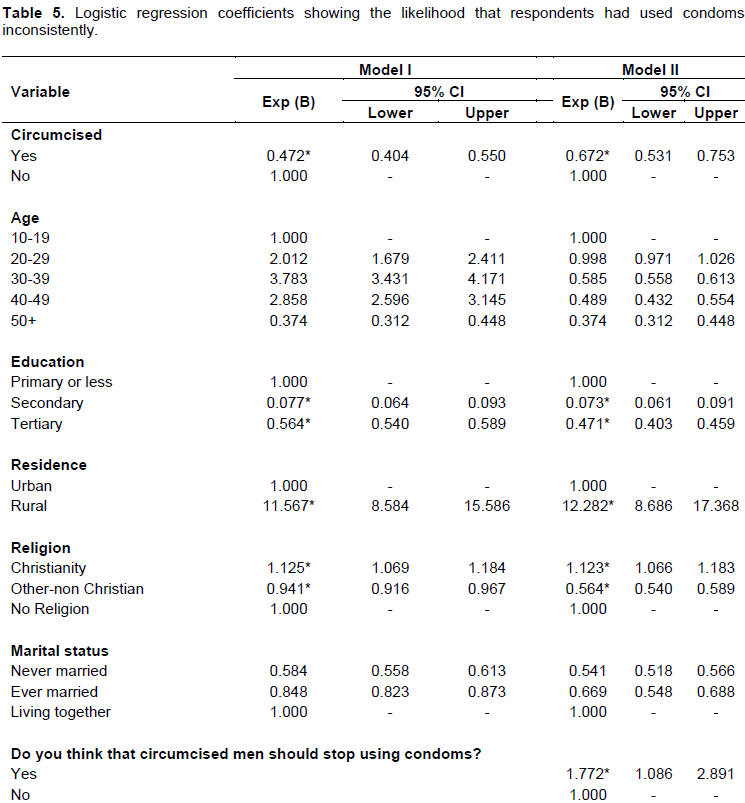

Male circumcision and inconsistent condom use

Table 5 shows logistic regression odds ratios of the association between male circumcision and inconsistent condom use among men. Results indicate that circumcised men were 53% less likely (OR=0.472; CI: 0.404-0.550) to use condoms inconsistently compared to uncircumcised men. Men with secondary (OR=0.077; CI: 0.064-0.093), and tertiary education (OR=0.564; CI: 0.540-0.589) were likely to report inconsistent condom use compared to those with primary or less education. When considering residence respondents in rural areas were 11 times (OR=11.567; CI: 8.584-15.586) more likely to report inconsistent condom use than men from urban areas. Results indicate that men of Christian religion were more likely (OR=1.125; CI: 1.069-1.184) to report inconsistent condom use than men of no religion, while men of other non-Christian religion were less likely to report in consistent condom use. There is no significant association between education and inconsistent condom use.

Model II results show that even after introducing behavioural variables, results indicate that circumcised men were less likely (OR=0.672; CI: 0.531-0.753) to report inconsistent condom use compared to uncircumcised men. Meanwhile men with secondary and tertiary education were less likely to report inconsistent condom use compared to men with primary or less education. There was residential difference in inconsistent use of condoms. For instance, men who reside in rural areas were 12 times more likely (OR=12.282; CI: 8.686-17.368) to report inconsistent use of condoms than men in urban areas. Christian men were also more likely (OR=1.123; CI: 1.066-1.183) to report inconsistent condom use than men with no religion. Men who were of the view that circumcised men should stop using condoms were more likely (OR=1.772; CI: 1.086-2.891) to have used condoms inconsistently than men who thought otherwise. Moreover, men who had seen information about safe male circumcision in the past four weeks were more likely (OR=1.210; CI: 1.179-1.446) to have not used condoms consistently. Age, marital status, alcohol consumption and HIV status were not significantly associated with inconsistent condom use.

Results in this study show that one quarter (25%) of men were circumcised and about 9% were of the view that circumcised men should stop using condoms. Circumcised men were less likely to have not used condoms consistently compared to men who were uncircumcised. This is not consistent with findings from other studies (Kibira et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2017) which have revealed that circumcision often gives circumcised men more freedom to have unprotected sex and in some instances to have many sexual partners. Decline in condom use is the most consistently expressed concern regarding male circumcision promotion and uptake, although our findings show the contrary. However, in Botswana there is need for more information and education about the actual benefits and disadvantages of circumcision to maintain consistent condom use.

It was found out that circumcised men were more likely to report multiple sex partners than uncircumcised men, when controlling for socio-demographic variables. Moreover, the odds of reporting multiple sex partners increased further with inclusion of behavioural variables. Some studies attribute HIV risk behaviours such as having multiple sex partners to behaviour risk compensation, where men change their sexual behaviours for the worse with the knowledge that their risk of infection is reduced (Riess et al., 2010; Andersson et al., 2011; Westercamp et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2014). A study by Riess et al. (2010) also showed that some men increased the number of sexual partners after undergoing male circumcision as part of the new program in Kisumu, Kenya, while others stopped using condoms consistently.

Evidence of risk compensation was also observed in the three randomized clinical trials that gave rise to the circumcision recommendation by UNAIDS in 2007. In another trial, circumcised men reported inconsistent condom use than uncircumcised men at the 4-12 and 13-21 months recall periods (Kibira et al., 2013). Further investigation into risk compensation in the Kenya trial (Mattson et al., 2008) demonstrated no marked increase in sexual risk behaviour among circumcised men, while in Uganda, inconsistent condom use was higher among circumcised men (Gray et al., 2012). In Botswana, a study on men’s willingness to undergo circumcision found that expressing willingness to be circumcised was associated with significant increase in the likelihood of having multiple sex partners (Keetile and Rakgoasi, 2014). The observation that circumcised men in this study had multiple sex partners is a notable possibility of behaviour risk compensation.

Meanwhile, men who were of the view that circumcised men should stop using condoms were more likely to have multiple sex partners and report inconsistent condom use. This also could be attributed to perceived risk compensation among these men. Risk compensation can result when perceived risks for HIV infection are lowered due to certain attitudes and beliefs about the protective benefits of circumcision (Eaton at al., 2011) among these men. These results clearly imply wrong beliefs and attitudes of men towards male circumcision’s protective benefits. Conversely, results from a study by Kong et al. (2012) in Uganda showed that uncircumcised men became significantly more likely than circumcised men to report multiple sex partners in the previous year and non-use of condoms at last sex with a non-marital partner. The magnitude to which risk compensation will moderate the protective benefits of a widespread scale-up of MC, such as that occurring in Botswana, need to be coupled with robust information, education and communication strategy. There is need to dispel some myths, attitudes and beliefs about safe male circumcision which may fuel risky behaviours. Sabone et al. (2013) observed that some wrong beliefs, myths and attitudes are key impediments to uptake of safe male circumcision among men in Botswana. They (Sabone et al., 2013) suggested the need for further information, education and communication about SMC to reduce the level to which risk compensation could moderate the protective effects of SMC.

Alcohol consumption was positively linked with having multiple sex partners and not with inconsistent condom use. Some studies have shown that alcohol consumption is the key driver of HIV/AIDS in Africa, especially through risk behaviours such multiple sex partnerships and inconsistent condom use (Leclerc-Madlala, 2009; Morojele, 2013; Braithwaite et al., 2014). Moreover, recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that alcohol use was found to be associated with HIV risk behaviours especially having multiple sex partners (Scott et al., 2013; Sales et al., 2012).

Furthermore, our findings indicate that HIV positive men were less likely to have multiple partners compared to HIV negative men. This indicates awareness of the possibility of re-infection among HIV positive men. Circumcised HIV negative men on the other had reported having multiple sex partners. Given this evidence, promotion of the SMC program without increased education and counselling among men may hinder progress in further HIV reduction (WHO, 2015), since circumcised men engage in risky sexual behaviour. Anderson and Cockroft (2012) observed that the belief in an exaggerated protective effect of SMC might lead to risk compensation.

They found that young men who held the misconception that MC provides full protection against HIV infection were more prone to have multiple sex partners. Despite the campaign about SMC having begun long time in Botswana, misconceptions about SMC are still common. This may undermine the efforts in the fight against HIV/AIDS, or even reverse the gains made in reducing HIV incidence.

There should be more studies designed to monitor post-circumcision risk compensation over time, in a context of active promotion of male circumcision as an HIV prevention strategy. This should be done within a context of providing free information, education and communication materials that dispel myths and beliefs about SMC promptly.

The emphasis should not only be on the protective benefits of male circumcision but also that risk compensation could significantly reduce or negate the protective effects of circumcision against HIV if certain attitudes and beliefs are unchecked.

According to Westercamp et al. (2014), it is very possible that the behavioural changes observed in circumcised men may reflect a form of cognitive dissonance in which the psychological state of conflict between attitudes, beliefs or behaviours result in realignment to decrease discomfort caused by the conflict-in which men re-evaluate their behaviours in light of the personal investment involved in getting circumcised.

Circumcised men showed high propensity of having multiple sex partners and not inconsistent condom use. Although this analysis is based on data derived from a cross-sectional survey and this has precluded conclusions about causal associations between circumcision and risk behaviours, results indicate the need for further information about actual benefits of SMC.

Although our findings provide vital insights about the association between male circumcision and HIV risk behaviours in Botswana where there is rapid scale up of male circumcision, there are some limitations. The main limitation of the study is the use of secondary data which has limited us to the variables within dataset. There is need for further qualitative investigation on male circumcision and HIV risk behaviours, especially that there are differentials in the association of male circumcision and two HIV risk behaviours variables-multiple sex partner and inconsistent condom use. The second limitation is that since data is derived from cross sectional survey, it limits this analysis because data on each participant are recorded only once, hence it would be difficult to infer the temporal association between a risk factor and an outcome.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Agot K, James K, Huong N, Odhiamb J, Onyango TM, Weiss N (2007). Male circumcision in Siaya and Bondo Districts, Kenya: prospective cohort study to assess behavioral disinhibition following circumcision. J. Acquired Immune Defic. Syndr. 44(1):6670-6678.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Andersson KM, Owens DK, Paltiel AD (2011). Scaling up circumcision programs in southern Africa: the potential impact of gender disparities and changes in condom use behaviours on heterosexual HIV transmission. AIDS Behav. 15(5):938-948.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bailey RC, Mugar R, Poulussen R, Abicht H (2002). The acceptability of male circumcision to reduce HIV infections in Nyanga Province, Kenya. AIDS Care 14(1):27-40.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Braithwaite RS, Nucifora KA, Kessler J, Toohey C, Mentor SM, Uhler LM, Roberts MS, Bryant K (2014). Impact of interventions targeting unhealthy alcohol use in Kenya on HIV transmission and AIDS-related deaths. Alcoholism: Clin. Exp. Res. 38(4):1059-1067.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eaton LA, Cain DN, Agrawal A, Jooste S, Udemans N, Kalichman SC (2011). The influence of male circumcision for HIV prevention on sexual behaviour among traditionally circumcised men in Cape Town, South Africa. Intl. J. STD AIDS. 22:674-679.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gray RH, Kigozi G, Kong X, Ssempiija V, Makumbi F, Wattya S, Serwadda S.D, Nalugoda F, Sewenkambo NK, Wawer MJ (2012). The effectiveness of male circumcision for HIV prevention and effects on risk behaviors in a post-trial follow up study in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS 26(5):609-615.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kebaabetswe P, Lockman S, Mogwe S, Mandevu R, Thior I, Essex M, Shapiro RL (2003). Male Circumcision: An acceptable strategy for HIV prevention in Botswana. Sexually Transmitted Infect. 79(3):214-219.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Keetile M, Rakgoasi SD (2014). Male circumcision: Willingness to undergo safe male circumcision and HIV risk behaviors among men in Botswana. Afr. Popul. Stud. 28(3):18-26.

|

|

|

|

|

Kibira SP, Sandøy IF, Daniel M, Atuyambe LM, Makumbi FE (2016). A comparison of sexual risk behaviours and HIV seroprevalence among circumcised and uncircumcised men before and after implementation of the safe male circumcision programme in Uganda. BMC Publ. Health 16(1):7-15.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kibira SPS, Nansubuga E, Tumwesigye NM (2013). Male Circumcision, Sexual Behavior, and HIV Status in Uganda. Demogr. Health Surveys 100:7-31.

|

|

|

|

|

Kong X, Kigozi G, Nalugoda F, Musoke R, Kagaayi J, Latkin C, Ssekubugu R, Lutalo T, Nantume B, Boaz I, Wawer M (2012). Assessment of changes in risk behaviors during 3 years of posttrial follow-up of male circumcision trial participants uncircumcised at trial closure in Rakai, Uganda. American J. Epidemiol. 176(10):875-885.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lagarde E, Dirk T, Puren A, Reathe RT, Bertran A (2003). Acceptability of male circumcision as a tool for preventing HIV infection in a highly infected community in South Africa. AIDS 17(1):89-95.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Leclerc-Madlala S (2009). Cultural Scripts for Multiple and Concurrent Partnerships in Southern Africa: Why HIV Prevention Needs Anthropology. Sexual Health 6(2):103-110.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mah TL, Halperin DT (2010). Concurrent sexual partnerships and the HIV epidemics in Africa: Evidence to move forward; in AIDS and Behaviour 14:11-16.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mattson CI, Bailey RC, Mugar R, Poulussen R, Onyango T (2005). Acceptability of male circumcision and predictors of circumcision preferences among men and women in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Care 17(2):182-194.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Morojele NK, Nkosi S, Kekwaletswe CT, Saban A, Parry CDH (2013). Review of research on alcohol and HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. South Afr. Med. Res. Council Pol. Brief pp. 1-4.

|

|

|

|

|

NACA (2014). Global AIDS response report progress report of the national response to the 2011 declaration of commitments on HIV AND AIDS pp. 1-82.

|

|

|

|

|

Nnko S, Washija R, Urassa M, Boerma JT (2001). Dynamics of male circumcision practices in North West Tanzania. Sexually Transmitted Dis. 28(4):214-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Riess HT, Achieng MM, Otieno S, Ndinya-Achola JO, Bailey CR (2010). When I Was Circumcised I Was Taught Certain Things: Risk Compensation and Protective Sexual Behavior among Circumcised Men in Kisumu, Kenya. PLoS ONE 5(8).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sabone M, Magowe M, Busang L, Moalosi J, Binagwa B, Mwambona J (2013). Impediments for the Uptake of the Botswana Government's Male Circumcision Initiative for HIV Prevention. Sci. World J. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/387508.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sales JM, Brown JL, Vissman AT, DiClemente RJ (2012). The association between alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among African American women across three developmental periods: A review. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 5:117-128.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shi CF, Li M, Dushoff J (2017). Evidence that promotion of male circumcision did not lead to sexual risk compensation in prioritized Sub-Saharan countries. PLoS One 12(4):e0175928.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Statistics Botswana (2009). The Botswana AIDS Impact Survey Report, Government Printers, Gaborone.

|

|

|

|

|

UNAIDS (2007). New Data on Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Policy and Programme Implications: Conclusions and Recommendations [Technical Consultation]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

|

|

|

|

|

Westercamp M, Jaoko W, Mehta S, Abuor P, Siambe P, Bailey RC (2017). Changes in Male Circumcision Prevalence and Risk Compensation in the Kisumu, Kenya Population, 2008-2013. J. Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 74(2):e30-e37.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Westercamp N, Agot K, Jaoko W, Bailey RC (2014). Risk Compensation Following Male Circumcision: Results from a Two-Year Prospective Cohort Study of Recently Circumcised and Uncircumcised Men in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Behav. 18:1764-1775.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wilson NL, Xiong W, Mattson CL (2014). Is sex like driving? HIV prevention and risk compensation. J. Dev. Econ. 106(1):78-91.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO) (2015). Progress Brief 2015- Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in priority countries of East and Southern Africa. Geneva.

|

|