ABSTRACT

The study aims to examine customers’ emotional reaction to brand collaboration, taking into consideration the possible combination of different brand equities using three experiments. Mobile phone is selected as the hypothetical product. Samsung is selected as the brand with the highest awareness in the mobile manufacture category whereas Burberry is selected as the brand with the highest awareness in the fashion category. Meanwhile, HTC and Bottega Veneta have the lowest brand awareness in the mobile and fashion category respectively. Four companies were selected to launch a hypothetical collaboration product. Analyzing the experiment samples’ data from china mobile phone market, the study findings revealed that consumer’s image congruence level (brand attitude/ brand relationship) of a product having two high brand awareness (High-High) is significantly greater than consumer’s image congruence for the same product having two different brand awareness (High-Low or Low-High). Consumer’s image congruence level (brand attitude/ brand relationship) for a product with two high brand awareness (High-High) is significantly greater than consumer’s image congruence for the same product with two low brand awareness (Low-Low) brands. A psychological framework is proposed in order to give marketers a new analytical tool in understanding and implementing effective brand collaboration.

Key words: Brand collaboration, brand awareness, image congruence, brand attitude.

Brand collaboration is co-operative marketing activities that involve short or long-term associations or combination of two or more individual brands. Brand collaboration can be represented by using multiple brands on the same product or by the association of brand names, logos, or other proprietary assets of the brand in promotions. Nowadays consumers are smarter. They rarely chose products based on emotional and not functional needs. Too many functionally similar products are competing in the same category and consumers have become more careful and cautious. Consumers get confused when they are faced with multiple products with similar functions. To thrive in this competition, products manufacturers came up with different tactic and one of the tactics is brand collaboration (Hamel et al.,1989).

Lots of brands have collaborated over the years in order to drive sales. Coca-Cola successfully collaborated with Diebels (a German beer producer) to market a new fruit beer called Dimix in 1998. Nike and Apple jointly launched Nike plus sports shoes that enable communication between the shoes and a runner’s iPod, which feature both brands’ logos. Samsung has launched in collaboration with Armani three times (2007, 2008 and 2010). The one launched in 2010 was a smart phone designed by Giorgio Armani. This latest-generation mobile masterfully combined Samsungs’ experience in technology with a design from one of the world’s best-known designer. The design from Armani gives exclusiveness and fashion to the cutting-edge technology, so that the product is not just simple mobile phone, but can have its unique concept satisfying customer’s emotional needs.

Aaker and Keller (1990) on brand extensions revealed that co-branding arrangements form positive consumer perceptions about a particular brand. In a report on Swedish firms in India, Paulsson (1986) found that the competitive firm licenses its brand name in order to exploit export opportunities. Marjit et al. (2007) provided several examples of brand name collaboration. Because brand name collaboration would expose one company to a fierce competition from the other one, brand name collaboration was not profitable in his analysis if the brand reputation of one company and the other company were sufficiently different. Beside, Aaker (1996) argued that brand personality could be linked with a brands’ emotional and self-expressive benefit. Thus, brand personality yields a basis for the consumer-brand relationship.

This study provided empirical evidence of the collaboration strategy related to consumers’ reaction different from Aaker and Keller’s conceptualization of consumer evaluation of brand extensions. The use of a superior brand will result in an upward shift of the market demand by means of altering the perception of the consumers about the product. Most companies have explored brand collaboration at one time or another. Prior research studied brand collaboration between one unknown brand and one established brand or two well-known brands, without taking into consideration the possible combinations of different brand equities (Rao and Ruekert, 1994; Simonin and Ruth, 1998; Voss and Gammoh, 2004).

A consistent finding in brand collaboration research is that a well-known, reputable brand improves consumers’ evaluation of an unknown brand. Brand collaboration research will benefit from a better understanding of how and when brand collaboration creates more positive evaluations (Keller, 2001).

In addition, Motion et al. (2003) indicated that collaboration can enhance the brand value. In their research, they proved that co-branding strategy reinforced brand values and reached new target groups (Motion et al., 2003; Paul et al., 2003). Marjit (2007) studied the possibility of cross-border brand name collaborations between two firms where superior brand enhances consumers’ valuation for the product in a Cournot-Nash framework and how a tariff on the reputed brand product affects the conditions for collaboration (Sugata et al., 2007; Debasmita and Arijit, 2014).

Kalafatis (2012) found that equivalent equity levels shared the benefits of the co-branding equally, while lower equity brands benefited more from the alliance than higher equity partners (Stavros et al., 2012). Different brand collaboration models contain different advertising’s persuasion message, emotional evaluation processes from consumers can influence success or failure of brand collaboration.

Marjit et al. (2007) provided a duopolistic model of brand collaboration and theoretically demonstrated that a collaboration agreement is likely to occur between the firms which are nearly ‘equal’ in terms of their initial brand reputation (Sugata et al., 2007). The study gives empirical tests for the ‘equal’ theory through three studies from the consumer emotional reaction viewpoint. Until now, little research empirically investigates how such combinations of brands with their different brand equities influence consumers’ judgments of the participating brands in brand collaboration strategy.

Consumer’ emotional reactions are concerns with consumers’ culture value. In particular, cultural characteristics can affect marketing decision making (Schwartz and Ros, 1995; Graham et al., 1988; Clark, 1990). Dawar and Parker (1994) found that the relative importance of ‘brand name’ and ‘retailer reputation’ as signals of quality for consumer products do not change across cultures. In fact, eventually success possibility of a brand collaboration deal between two firms depends heavily on market consumers’ emotional reaction from culture values. How is demonstration of the emotional reaction on brand collaboration?

Until now, little research about the issue is known to us. In this paper, we introduce three items respectively called image congruence, brand awareness and brand relationship to depict the consumers’ emotional characteristics from brand collaboration. The study analysis differs from that of the aforementioned research in some important ways. Unlike them, we propose a new analytical psychological framework of brand collaboration that allows marketers to understand the effects as well as importance of collaboration.

The study focuses on consumers’ emotional reaction on combination products of different brand collaboration models through three studies based on Chinese experimental data and identifies conditions when and how the level of image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship can be strengthened by its partner brand having greater reputation.

Hypothesis development

Image congruence and brand collaboration

An individual’s behavior is in part a function of his self-image and the way in which he wishes others to see him (Birdwell, 1968). Consumption behavior of consumer is a story of representing themselves and also how you want to let others perceive yourself. Consumer represent themselves as they project their image or the image they want to be to the product and eventually congruent it.

A more meaningful way of understanding the role of goods as social tools is to regard them as symbols serving as a means of communication between the individual and his significant references (Dolich, 1969; Grubb and Grathwohl, 1967; Ericksen, 1996). Specifically, brand is considered to have a particular ‘image’ that mirror the self-concept of the typical user of the brand and consumers were thought to prefer products with images that were congruent with their self-concepts. In this purchasing process, consumers attempt to evaluate a brand. This matching process including brand image and consumer’s self-concept is referred to as self-congruity (Graeff, 1996; Levin et al., 1996; Levin, 2002).

Sirgy (1982) argued that self-evaluation involves a comparison between a perceived self-image outcome and a self-expectancy, but the objective is an evaluation of the relative “goodness” of the perceived self-image outcome, and this process is mostly guided by the need for self-esteem.

Partners in a brand alliance should be similar or dissimilar in brand image to foster favorable perceptions of brand fit, using a Bayesian nonlinear structural equation model and evaluations of 1,200 brand alliances, Ralf van der Lans et al. (2014) found that similarity effects are more pronounced than dissimilarity effects. Therefore, the first hypotheses are:

H1a: Consumer’s image congruence level for a product having two high brand awareness (High-High) brands is significantly greater than consumer’s image congruence for the same product having two different brand awareness (High-Low or Low-High) brands.

H1b: Consumer’s image congruence level for a product having two high brand awareness (High-High) brands is significantly greater than consumer’s image congruence for the same product having two low brand awareness (Low-Low) brands.

Shavitt (1989) noted that attitudes may work as a means of maintaining self-esteem and creating identity, with individuals associating themselves with liked or positively regarded objects. Attitude can manage self-esteem once it is formed in a good way, and also can be created by a brand association.

Aaker (1996) argued that positive brand attitude could be formed by a positive brand association among consumers. This brand association between brand and consumer also affects their consumer-brand relationship. All these activities are took place emotionally in mind. Fournier (1998) noted that emotional experience can strengthen consumer-brand relationship.

In addition, Wyner (1999) argued that product association between brand (product) and consumer helps to shape the brand relationship. Birdwell (1968) argued that the self-image was directly related to purchasing behavior. This purchasing behavior is able to enhance self-concept at the same time.

In the process of purchasing and consumption of goods, self-concept of an individual will be sustained and buoyed if consumer believes the good he has purchased is recognized publicly and classified in a manner that supports and matches his/her self-concept (Heath and Scott, 1998). This argument suggests that consumer may purchase goods in order to develop a particular self-concept rather than functionality. Based on these researches, this study examines the following hypotheses:

H7: The higher consumers’ congruence level, the higher consumers’ brand attitude level.

H8: The higher consumers’ congruence level, the higher consumers’ brand relationship level.

Brand awareness and brand collaboration

Awareness of a brand or a product is considered as an important determinant when consumers decide their purchase. Various standard measures, such as aided and unaided brand name recall and top-of-mind awareness, rest on the assumption that the ability of the consumer to remember a brand or product will strongly affect the probability of its being considered for purchase.

Hoyer (1984) argued that the consumer in many purchase situations is a passive recipient of product information at best and one who tends to spend minimal time and cognitive effort in choosing among brands. When it comes to high concerning product (usually expensive or relative to health and safety), consumer tends to decide more based on the brand awareness, which is related to their experience and reliability. Moreover, in situations involving common repeat-purchase products, consumers may choose a brand on the basis of a simple heuristic (for example, brand awareness, and pricing) and then evaluate the brand subsequent to purchase. Accordingly, the following hypotheses will be examined:

H2a: Consumer’s brand attitude for a product having two high brand awareness (High-High) brands is significantly greater than consumer’s brand attitude for the same product having two different brand awareness (High-Low or Low-High) brands.

H2b: Consumer’s brand attitude for a product having two high brand awareness (High-High) brands is significantly greater than consumer’s brand attitude for the same product having two low brand awareness (Low-Low) brands.

Brand awareness is also interpreted in name familiarity. Janiszewski (1988) suggest that familiarity leads to greater liking, even without the mediation of conscious awareness. Other research found that brand awareness itself might be more important than other characteristics such as quality in making brand choice decisions.

Hoyer and Brown (1990) argued that consumers were more likely to choose a familiar brand versus an unknown brand, even though they are informed that the unknown brand has higher quality. Macdonald and Sharp (1996) indicated important effects on consumer decision making by influencing which brands enter the consideration set, and it also influences which brands are selected from the consideration set. Enhancing brand name awareness thus can have important competitive implications since it may hinder consumers’ memory for competitors’ brand names. Consumers respond strongly and decide to buy only familiar, well-established brands. Brand awareness is also view as a part of brand equity.

Aaker (1991) proposed that brand awareness, brand associations, perceived quality, brand loyalty and other proprietary assets were the five assets of brand equity. In the context of brand equity, brand awareness refers to the strength of a brand’s presence in consumers’ minds. By this reason, brand awareness is conceptualized as consisting of both brand recognition and brand recall in the present study.

Aaker (1996) argued that brand awareness could be a driver of brand choice and even loyalty in some context, and reflects the salience of the brand in the customers mind. He also indicated that several levels of awareness, which include recognition, recall, top-of-mind, brand dominance, brand knowledge, and brand opinion. Hence, the following hypotheses are offered:

H3a: Consumer’s brand relationship of a product having two high brand awareness (High-High) is significantly greater than consumer’s brand relationship for the same product having two different brand awareness (High-Low or Low-High) brands.

H3b: Consumer’s brand relationship for a product having two high brand awareness (High-High) brands is significantly greater than consumer’s brand relationship for the same product having two low brand awareness (Low-Low) brands.

Collaboration product and non-collaboration

The evaluation of an object is affected by how the evaluation will fit with other related attitudes held by the consumer according. In the collaboration strategy, pairing two brands can possibly create positive perception that a brand has positive effect with one that has less positive or even negative.

More specifically, it is assumed that consumer’s perception of the unknown or less preferred brand may be enhanced if one unknown or less preferred brand make a collaboration product with a well-known brand,. In a competitive marketplace, many companies are trying to get more attention from consumers by combining two brands in an effort to create the perception of increased worth of the product (Carpenter, 1994; Erdem and Swait, 2004).

Similarly, if we feel positively toward ourselves, we will tend to like anything associated with us (Began, 1992; Levy and Lazarovich-Porat, 1995). As earlier mentioned, it is possible to argue that if we have positive feeling toward something (more likely an object), we tend to like anything related with it. Supposed that brand A makes a product collaboration with brand B, if someone feel positively on Brand A, then he is likely to have a positive feeling toward on brand B at the same time. This point leads to the following hypotheses:

H4: Consumer’s image congruence level for a collaboration product is significantly greater than non-collaboration product.

H5: Consumer’s brand attitude for a collaboration product is significantly greater than non-collaboration product.

H6: Consumer’s brand relationship for a collaboration product is significantly greater than non-collaboration product.

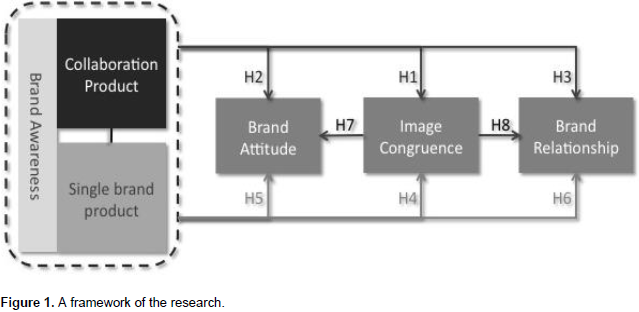

The problems involved in the above studies are illustrated in Figure 1.

Design of the research

Hypothetical product and questionnaire design

Mobile phone is selected for the hypothetical product type among several products (such as car, laptop, clothes, beverage etc.). Since mobile phone has high conspicuousness and consumers are more likely to evaluate it in terms of symbolic criteria.

In addition, as purchase of mobile phone is a high-cost purchasing decision, consumers evaluate competitive product (or brand) in the same product category before they make a decision to purchase it (high commitment). It is important to note that several collaborated mobile phones exist already in the market. Since Motorola-Coach phones early in 2000, Nokia-Samsung-LG also made collaboration project many times. Because of this reason, it can be safely assumed that respondents of questionnaire may be familiar with this kind of product and the way they collaborate.

Brand awareness is usually perceived as one of the component of brand equity. In some contexts, it can be a driver of brand choice and even loyalty (Aaker, 1996). According to Aaker (1996), brand awareness somehow acts as a trigger when customers see particular brand, and reminds customers the features of the brand in their mind.

In this research, we will measure and see how the respondents react when they are asked about sample brands. Because awareness levels can often be affected dramatically by cueing symbols and visual imagery (Aaker, 1996), in the design of questionnaire for verifying awareness, we put the logo of each company on the top of questionnaire to get the maximized result from the respondents.

The items of brand awareness test came from Aaker (1996). In this pretest, we use seven-point Likert scales (semantic differential) for each items (total of ten items) to evaluate ten brands from two different categories. To test the reliability of construct of brand awareness, a Cronbach’s alpha test is performed (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.851). In the test Cronbach’s alpha exceeds the standard cut-off point (0.700), so that all the items in the pretest are chosen for the further test (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). The items and scales used to measure the brand awareness are listed in the Appendix A.

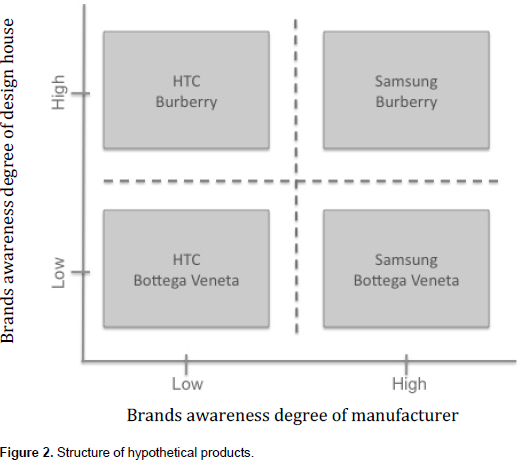

Using the ten items of the brand awareness scale used in the pretest, we commenced an online survey to determine which brands to be used in the main test later. Fifty people participated in the survey and the results indicated that Samsung was selected as the highest brand awareness in the mobile manufacture category whereas Burberry was revealed to have the highest brand awareness in the fashion design house category. Meanwhile, HTC and Bottega Veneta have the lowest brand awareness in each of mobile manufacture and fashion design house category. Hence, four companies have been selected to launch a hypothetical collaboration product. One company from each category made a collaboration combination, comprised in four different combinations as shown in Figure 2.

Measures

Image congruence

To measure how the consumers regard their self-image as same with brand image, four items with seven-point semantic differential scales were used for the variable. One item among those four items came from part of the work made by Aaker et al. (2004) and others were made to measure the degree of image congruence appropriately (Sirgy et al., 1991, 1997). The semantic differential scales were assessed for reliability by calculating Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for each scale (Cronbach’s alpha=0.892, n=225) and considered as standard cut-off point for basic research (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). Respondents were asked to indicate the degree that they thought described target brand and their self-concept well at the same time in order to test hypothesis H1a and H1b, H4, H7 and H8. The anchor points for the semantic differential scales ranged from 1 to 7 (1: Extremely negative, 7: Extremely positive). A list of items (statements) and scales used in the semantic differential scales for each brand was contained in Appendix B.

Brand attitude

Four questions were included in the questionnaire for brand attitude scale. These questions were given after the respondents read the description about hypothetical product. Attitude of the respondents towards each brand was measured on a seven point semantic differential scale ranging from 1 to 7 (1: Extremely negative, 7: Extremely positive). Specifically, the respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they were loyal to relevant brand in order to test hypothesis each of H2a and H2b, H5, and H7. These questions were from Aaker et al. (2004). The reliability of the questionnaire were also verified (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.906, n=225). A list of items (statements) and scales used in the semantic differential scales for each brand is contained in Appendix B.

Brand relationship

The respondents’ responses to four questions about the brand relationship were used to test hypothesis H3a and H3b, H6, and H8. All items were measured on a seven point semantic differential scale ranging from 1 to 7 (1: Extremely negative, 7: Extremely positive). Three of four items were from part of the work by Aaker et al. (2004) and another one was from Kressmann et al. (2006). The Cronbach’s alpha of 0.927 (greater than 0.700 standard cut-off point) indicates that the items present the level of brand relationship well. A list of items (statements) and scales used in the semantic differential scales for each brand are contained in Appendix B.

DATA COLLECTION AND METHOD

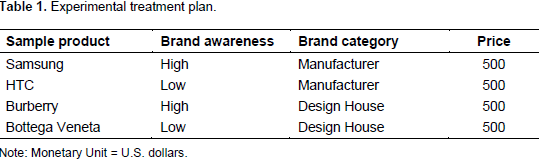

A total of randomly chosen 225 people (7 of them were invalid) were requested to fill the questionnaire out through two methods including e-mail and were informed that they could voluntarily participate in this research about brand product collaboration (Table 2). They were administered a detailed questionnaire designed to assess the image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship consisting of 12 questions. For further assessment, all respondents were asked to fill the same questionnaire for each combination of collaboration as well as non-collaboration product, each brand produced same product. All the questions were administered on a seven-point semantic differential scale. The Cronbach’s coefficient was used in order to validate the reliability of the questionnaire. Effectiveness of the relationship on brand image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship were verified by means of means difference analysis and linear regression results. The experiments were a 2 x 2 design with mobile manufacture (Samsung, HTC) and fashion design house (Burberry, Bottega Veneta) (Table 1).

Experiment

Experiment 1: The difference of brand awareness of collaboration product

The experiment design and testing method: Study respondents (n=218) were randomly assigned to the first experiment. The experiment respondents were students and workers of Shanghai Jiaotong University. After reading a brief introduction on the cover page of questionnaire, respondents were instructed to read the hypothetical product concept to answer the questions well. Thquestionnaire consisted of three parts. In the first part, we introduced the hypothetical product and how it was made by two different companies (mobile manufacture and design house), and also informed that the price of the product was same for each combination of companies. In the second part, a main questionnaire was given to be answered including the three dependent measures, which were Image congruence, Brand attitude and Brand relationship. In the last part, each respondent was asked to answer general information of their characteristic, which include gender, nationality, age, education and employment status.

The first experiment aims at testing H1, H2 and H3 through the empirical test if the difference of brand awareness of collaboration product affects image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship. Total of 6 different cases consisted of different level of brand awareness product were tested. According to each company’s brand awareness, two of high-high and high-low (low-high), one of high-high and low-low, one of high-low and low-high, one of high-low and low-low and one of low-high and low-low were made.

Each of H1, H2 and H3 consisted of ‘a’ and ‘b’. Eventually six cases were tested in the first experiment. The first step in hypothesis testing was to examine whether any of the collaboration brand affect the dependent variables. According to the Hypothesis H1, H2 and H3, each of image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship had to be affected by series of different collaboration brand mix. In the test, a series of ANOVA were run with different combination of collaboration brand mix (Cell means are presented in Table 2).

H1 for image congruence reveals significant result. The test showed that low-high combination was significantly affected by brand awareness difference (mean difference=3.317, Sig. =0.015). However, when low brand awareness design house was working with high brand awareness manufacture, there was no significant image congruence between two high brand awareness combination, and one high - low brand awareness combination (Mean difference =2.732, Sig =0.068), in support of half of H1a.

When two high brand awareness combination met two low brand awareness combination, there was strong image congruence between customers and brands (Mean Difference=6.366, Sig. =0.000). Unlike H1a, it was clearly proved that two low awareness brand combination could not support customer’s image congruence level. Customers believed more in the manufactures commitment than in what the design house collaborates, in support of H1b.

H2 for brand attitude test showed that there was no significant interaction between brand awareness differentiation and brand attitude level. Specifically, when two high awareness brand combination collaborated with one high awareness manufacturing brand and one low awareness design house brand, there was no difference on brand attitude (Mean Difference=2.146, Sig.=0.260).

In the same manner, when one low awareness manufacturing brand and one high awareness design house brand collaborated with two high combination, no difference was still observed (Mean Difference=2.805, Sig.=0.079), which is not in support of H2a. As we can see in Table 3, when two high awareness brand companies were compared to two low awareness brand companies, there was a significant difference in brand attitude. People were usually hesitant when they choose something that do not have enough information or not familiar with, in support of H2.

H3 for brand relationship postulated that brand relationship would be higher in the case of two high awareness brand combination compared to those brand combination having lower awareness. The experiment showed that there was no significant relationship between one manufacture brand of high awareness and one design house brand of low awareness, which did not support H3.

Specifically, when high awareness of design house brand compared to low awareness of design house brand, customers’ brand relationship towards the case were same, that is, difference of design house could not affect the brand relationship (Mean Difference=2.463, Sig.=0.126), which did not support H3a. However, difference of manufacture could affect the customers’ brand relationship. In the case of different manufactures, customer’s brand relationship is significantly strong greater than the combination of low manufacture (Mean Difference=3.146, Sig. =0.026), in support of H3a.

Since high awareness brand had more chance to communicate and interact with customers, their brand relationship also would be affected positively compared to those not interacting with customers enough. Specifically, when two high awareness brands collaborated, their brand relationship was higher than those of two low awareness brands collaborated (Mean Difference=6.073, Sig. =0.000). Thus, the results supported H3b but not H3a.

Empirical results from the research provide support for previously untested concepts from collaboration strategy and consumer’s image congruence theory in terms of brand awareness, and also provide understanding some of the factors that are associated with brand attitude as well as brand relationship. A major tenet of image congruence theory is that brand is considered to have a particular ‘image’ that mirror the self-concept of the typical user of the brand and consumers are thought to prefer products with images that are congruent with their self-concepts (Sirgy, 1982).

The statistical results suggest that their image congruence level (when the sum of brand awareness of two brands is higher) is also higher than those (when the sum of brand awareness of two brands is lower). This result is supported by the statistical results of High-High versus Low-High, High-High versus Low-Low, High-Low versus Low-Low and Low-High versus Low-Low combination.

Consequently, a key aspect of collaboration strategy is that understanding the degree of brand awareness associated in the collaboration strategy when some companies seek for their partner to collaborate. Keller (2003) argued that brand awareness is the consumer’s ability to identify a brand under different conditions. Since consumers could recall a small number of brands but recognize many different brands, spontaneous awareness is a key variable in consumer behavior (Laurent et al., 1995).

The result of the test also proved that consumers tend to congruent their image more on the relatively high brand awareness product compare to its comparable product. Even though it can’t conclude that consumer’s image congruence level for a product having two high brand awareness (High-High) brands are significantly greater than consumer’s image congruence for the same product having two different brand awareness (High-Low or Low-High) brands or the same product having two low brand awareness (Low-Low) brands in all cases (As Samsung-Burberry versus Samsung-Bottega Veneta combination did not support of H1a), it is still appropriate to conclude that there are significant relationship between the level of brand awareness and image congruence level.

Consumers do not always spend a great deal of time or cognitive effort in making purchase decisions. They often try to minimize decision-making by using a heuristic such as “buy the brand I have heard of” or “choose the brand I know” and then purchase only familiar, well-established brands (Keller, 1993). When both companies associated with collaboration project have low brand awareness, the statistical results reveal that they do not generate distinct benefit from collaboration project. It is hard to let customers congruent their image to the product because none of brands in the collaboration project have incentive for customers to recall.

Macdonald and Sharp (2003) also argued that brand awareness plays an important role in consumer decision-making by influencing which brands enter the consideration set. Consumer’s perception of quality is usually based on the belief that the brand has high familarity, the quality of the product is also believed to be high. High-perceived quality is said to drive a consumer to choose one brand above competing brands (Yoo et al., 2000).

Sirgy (1982) proposed that consumers will be motivated towards positively valued products to maintain a positive self-image; and will purchase image congruent products to promote “self-consistency” and self-esteem. In the case of H1b, it is very clear that customers tend to congruent their image when the collaboration product is consist of two brands of high brand awareness compared to two brands of low brand awareness. Like what Sirgy argued, High brand awareness product give greater motivation to customers to maintain better self-image.

The statistical results show that respondents tend to congruent their image more to those having greater brand awareness combination than lower brand awareness combination in the most cases of collaboration. It can be seen that the brand of high awareness can affect the brand of low awareness associated in the collaboration project in the way of delivering a motivation of high self-esteem to customers. The results show that only two cases of High-High versus Low-Low and High-Low versus Low-Low have significant brand attitude effect and also support H2b. It is quite clear that the likelihood of choosing the brand of high awareness is extremely high when customers consider their choice between two different combinations to have distinct brand awareness difference.

The statistical results support H3b and partially support H3a. When the gap of brand awareness is big, brand relationship toward the collaboration combination consisting of two high awareness brands is strong. A relationship between the brand and the consumer results from the accumulation of consumption experience (Evard and Aurier, 1996).

Additionally, Blackston (1992) stated that understanding the relationship between the brand and the consumer requires observing two things. As we can see in the Table 3, when brand attitude is high, the brand relationship is also high. This means consumer’s attitude towards the brand is positively related to its brand relationship as well. Keller (2001) suggested that brand judgment (brand attitude) creates an intensive and active consumer-brand relationship.

The study indicates that higher brand awareness collaboration combination would have higher image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship, which is represented as H1a:b , H2a:b and H3a:b. However, those hypotheses (including H1a, H2a and H3a) are only supported partially but not entirely by the experiment. Hence we are not able to determine that High-High versus High-Low (or Low-High) has significant difference on three dependent variables. The hypotheses are strongly supported by statistical measures about H1b, H2b and H3b. Therefore, we can conclude that high brand awareness brand can improve evaluation for its associated brands’ (partner brand) image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship (only in the case of High-High versus Low-Low).

Experiment 2: The difference of brand awareness of single brand product

Respondents (n=218) were the same respondents assigned to the first experiment. The method of second experiment was exactly the same with the first experiment. The hypothetical product consisted of non-collaboration product produced by a single brand. The questionnaire consisted of three parts just like the first experiment. In the first part, the hypothetical product was introduced and made by one single company but the similar product. In the second part, a main questionnaire was given to be measured including the three dependent measures (Image congruence, Brand attitude and Brand relationship). In the last part each respondent was asked to answer general information of their characteristic, which included gender, nationality, age, education and employment status.

Second experiment was designed to test H4, H5 and H6 through the empirical tested if the difference of brand awareness of single brand product affected image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship in the comparison of collaboration brands. Total of eight different cases consisted of collaboration brands and non-collaboration brand were tested. Each of four collaboration brand combinations had two single brand mixes. Eventually eight cases were tested in the second experiment. The first step in hypothesis testing was to examine whether there was a significant differences between collaboration brand and non-collaboration brand affecting the dependent variables.

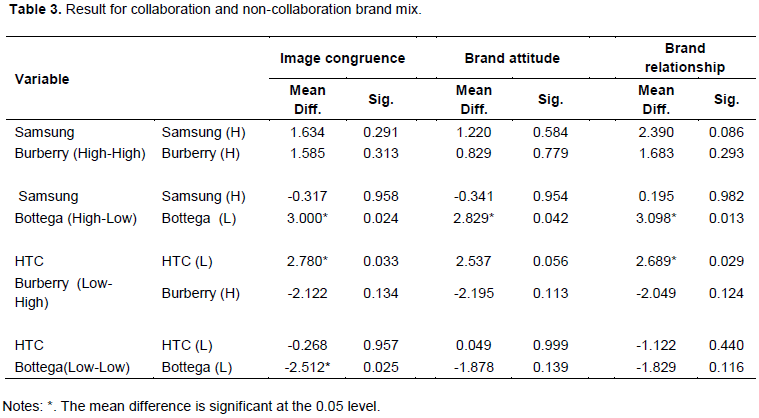

According to the Hypothesis H4, H5 and H6, each of image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship had to be affected by series of different brand collaboration and non-collaboration brand combination. In the test, a series of ANOVA were run with different combination of brands mix (Cell means are presented in Table 3).When brand awareness of collaboration brand was high for its two associated brands, there was no significant difference of image congruence level compared with high awareness of manufacture brand (Mean difference=1.634, Sig. =0.291) and high awareness of design house brand (Mean difference=1.585, Sig. =0.313). Bottega Veneta, which has low brand awareness collaborated with Samsung with high brand awareness, there was a significant difference of image congruence level when Bottega Veneta produced a similar product by itself (Mean difference=3.000, Sig.=0.024).

In the meantime, Samsung did not get any advantages from collaborating with Bottega Veneta, which has low brand awareness (Mean difference= -0.317, Sig. =0.958). Furthermore, the result showed that Samsung had negative effect from collaborating with Bottega Veneta in terms of image congruence. High awareness brand doesn’t get any advantages from the collaboration strategy (High-Low was in support of H4 only compared with Bottega Veneta) (Table 3). In the case of Low-High, the result showed that low awareness manufacture brand got positive from collaboration strategy rather than the product produced by themselves (Mean difference=2.780, Sig.=0.033). However, when High awareness design house collaborated with low awareness manufacture, there was no significant effect in image congruence perspective (Mean difference= -2.122, Sig. =0.134). Specifically, when HTC, which has low brand awareness, collaborated with Burberry (High brand awareness), there was positive effect on image congruence.

In the case of Low-Low collaboration combination, when HTC produced the mobile phone itself, there was no significant difference of image congruence level compared to collaboration combination (Mean difference= -0.268, Sig. = 0.957). Moreover, when Bottega Veneta produced the mobile phone itself, even they could get better image congruence from customers (Mean difference= -2.512, Sig.= 0.025). H5 for brand attitude test revealed that only High-Low collaboration group was significantly different compared to non-collaboration group. When Samsung and Burberry made a mobile phone independently, the brand attitude of its collaboration case did not have significant difference (each Mean difference=1.220, 0.829 and Sig. = 0.584, 0.779), and this result does not support H5.

Specifically, when Samsung and Bottega Veneta collaborated, consumer’s brand attitude towards them was significantly greater than Bottega Veneta itself (Mean difference= 2.829, Sig. = 0.042), in support of H5. But the opposite is not valid. When Samsung produce a mobile phone itself, they could be more successful compared with the collaboration with low awareness brand (Mean difference= -0.341, Sig. = 0.954), not in support of H5. In the same manners, Burberry could not get successful result from collaboration with HTC, as HTC has low brand awareness (Mean difference = -2.195, Sig. = 0.113), not in support of H5. HTC also had no significant effect from their collaboration with Burberry, which has high brand awareness (Mean difference= 2.537, Sig. =0.056). For the Low-Low combination, both HTC and Bottega Veneta have insignificant difference in brand attitude perspective (each Mean difference= 0.049, -1.878 and Sig. =0.999, 0.139), not in support of H5.

When Samsung and Burberry collaborated, there was no significant brand relationship difference with Samsung or Burberry itself (each of Mean difference= 2.390, 1.683 and Sig. =0.086, 0.293), not in support of H6. However, the collaboration combination of Samsung and Bottega Veneta had significant difference of brand relationship compared with the product produced by Bottega Veneta itself (Mean difference= 3.098, Sig. =0.013), in support of H6. When Samsung produced the product itself, there was no significant difference compared with collaboration combination with Bottega Veneta (Mean difference=0.195, Sig. =0.982). In the same manner, HTC could get benefit from the collaboration strategy that they could not get if they produced it by themselves (Mean difference =2.683, Sig. =0.029), in support of H6.

Burberry has no advantage from the collaboration strategy as Burberry’s brand awareness is already high (Mean difference= -2.049, Sig. = 0.124). In the case of low and low collaboration combination, insignificant result was observed (each Mean difference= -1.122, -1.829 and Sig. =0.440, 0.116), not in support of H6. This result tends to follow the result of H4 (image congruence). When there is a collaboration project between two different brand awareness companies, the one who gets the benefit from the project is the brand of low awareness regardless of its brand category. The results of this study reveal that High-Low and Low-High collaboration combinations can favorably influence each of its associated brands of low brand awareness across all dependent variables (image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship).

Samsung-Bottega Veneta versus Bottega Veneta itself is an example of this. H4 for image congruence revealed insignificant result. The test showed that none of single brands had significant difference compared with its collaboration brand combination. Collaboration effect of the combination of High-Low and Low-High were significantly greater than one single brand of low brand awareness. When the combinations of Low-Low and High-High, however, did not have significant effect compared with the subjects assessed independently.

The results of this research shows that the reputable brand in the collaboration tended to assist another reputation-less brand in the way of conveying coincided self-concept. Once collaboration strategy gets image congruence’ level enhanced, this will affect the level of brand attitude and brand relationship. If the new product in the collaboration carries both brand names, the role of both brand names in the collaboration is important, as one brand may carry greater weight than the other because of its strength as a product category specific brand (Park et al., 1996). The statistical results show that the level of brand attitude and brand relationship tends to be greater than single brand only in the occasion that the level of image congruence having significant difference.

Experiment 3: Relationship among image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship

The third experiment aims to test H7 and H8 based on the result of the first and second experiments by determining whether the image congruence level affects brand attitude and brand relationship. The respondents (n=218) were the same respondents who were assigned to the first and second experiments, but this time they did not participate directly in the experiment. This experiment was performed by comparing the questionnaire result of the image congruence against the result of brand attitude and brand relationship. To test if the image congruence affects its brand attitude and brand relationship, each result of the four kinds of brand collaboration (High-High, High-Low, Low-High, Low-Low) was derived from the questionnaire.

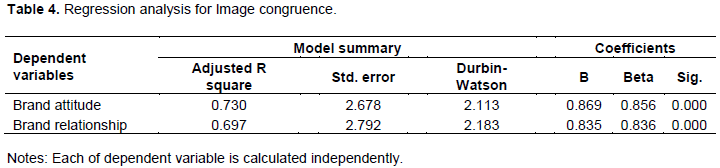

The other four non-collaboration brand (Samsung, HTC, Burberry, Bottega Veneta) set was not chosen because the purpose of this research is to find out whether the image congruence of product collaboration affects its brand attitude and brand relationship. According to the Hypothesis H7 and H8, each of brand attitude and brand relationship had to be affected by image congruence derived from series of different collaboration brands. In the test, the linear regression analysis was run with each of dependent variables, which were brand attitude and brand relationship. The linear regression model can access the effects of the image congruence (predictor variables) on the responses (Brand attribute, Brand relationship). Moreover, it can be used for predicting values of these two response variables from a collection of image congruence (Cell means are presented in Table 4).

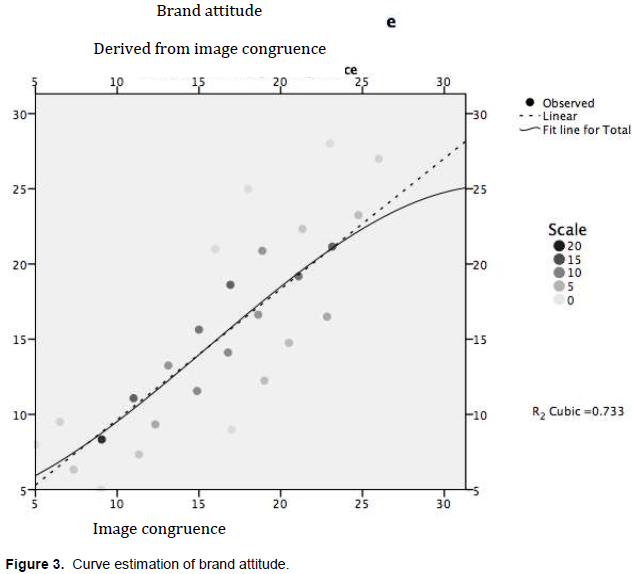

For the test of H7 and H8, all of the measures achieved high reliability level (ranging between 0.697 and 0.730). A series of comparison were conducted to test the hypotheses. The results from comparison tests are reported in Table 4. For the test of H7, we proposed that the brand attitude for the product was also high when the image congruence level for the product was high. As we can see on Table 4, adjusted R square indicates that there is a significant relationship between image congruence level and brand attitude level positively (Sig. =0.000<0.05). This regression model can explain 73% of the entire variance (Adjusted R square=0.730>0.6).

Moreover, the means of coefficients shows that the coefficient of brand attitude is significantly important (B=0.869) and is supported by the mean of Beta (Beta=0.856). We tested whether an autocorrelation existed in the linear regression model. The mean graph in Figure 3 shows the image congruence level significantly influences the brand attitude in positive way. This observation was also supported by statistical analysis. It is important to note that there was no collinearity in statistics, in support of H7 because the regression model was performed in the condition of one dependent variable.Linear regression results pertaining to effectiveness of the image congruence on brand relationship are shown in Table 4.

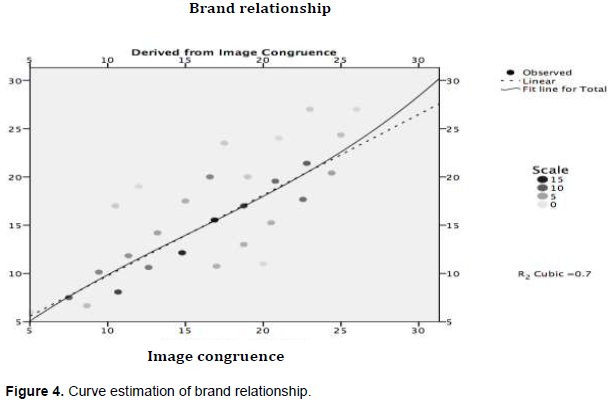

The same pattern of results was found for brand attitude. Consistent with the hypothesis, independent variables explain 69.7% of the variance in brand relationship (Adjusted R square=0.697>0.6). As shown in Table 4, adjusted R square indicates that there is a significant relationship between image congruence level and brand attitude level positively (Sig. =0.000<0.05). Moreover, the means of coefficients shows that the coefficient of brand relationship is significantly important (B=0.835) and is supported by the mean of Beta (Beta=0.836). The mean graph in Figure 4 shows the image congruence level is related positively to brand relationship. For the test of H8, the collinearity statistics was also not performed in the same reason of H7. Each of Tolerance and VIF mean would be 1 equally.

The purpose of H7 and H8 is to define how image congruence affects brand attitude and brand relationship. The statistical results prove that brand attitude and brand relationship have significant positive relationship with image congruence. All these findings explain that consumers do not only consider the functionality of a product, they are also concerned about the self-image (‘how I look like with a product’). A product is not a simple functional device, but something that tells about self-image. That is why individuals tend to buy brands whose personalities closely correspond to their own self-image.

Once this image congruence affects brand attitude, then it influences consumers’ brand choice. A brand that the consumer holds a strong attitude towards to perform better should be in alliance with one with weak consumer attitude (Wallendor and Arnould, 1988). This is why High-Low combination is more positively related to the three dependent variables than single brand with low brand awareness in the experiment 2. Provided that less reputable brand can get more privileges through the test if a brand which has high brand awareness collaborates with reputable brand.

The results provide useful information for the mobile industry and luxury brand. One of the major implications of this study is that there is a clear evidence of collaboration effect, that is, the reputation from superior brand affects reputable-less brand when reputable-less brand meet reputable brand, which may strengthen reputable-less brands’ reputation. Furthermore, even image congruence effect can also be delivered to reputable-less brand and enhance it at the same time.

The study focuses on reflection of consumers’ emotional reaction on brand collaboration through three studies based on Chinese consumers’ experimental data. Products collaboration usually has appeal point on emotional and not functional salience. This is the most prominent difference with other competitors since consumers want something different that can satisfy their personal special and unique needs. Among the variety of marketing strategies, brand collaboration might somehow stimulate these needs of present consumers.

Prior research on brand collaboration has narrowly focused on establishing differences in mean quality evaluation when an ally is used. The relative research supports the notion that collaboration with a reputable brand can enhance consumer’s attitude as well as consumer relationship toward the brand. Our work sheds light on when and with whom collaboration strategy is effective in consumer’s emotional reaction. This research strengthens earlier research by proving that collaboration with reputable brand (Samsung and Burberry) enhanced evaluations of less-reputable brands (HTC and Bottega Veneta). Finding and selecting the right partner to form brand collaboration is an important marketing strategy. This study also provides insights into its underlying causes of brand collaboration from a new perspective.

In this study, we propose a new analytical framework of brand collaboration that allows marketers to understand the effects as well as importance of collaboration. Our work identifies conditions when and how the level of image congruence, brand attitude and brand relationship can be strengthened by partnering with a brand with greater reputation. Consumer’s image congruence level (brand attitude/ brand relationship) for a collaboration product is significantly greater than non-collaboration product. These results are consistent with the notion of the ‘win-win’ that could enhance for less reputable brand collaboration with a reputable partner brand.

A reputable brand could enhance consumers’ brand attitude and brand relationship through the image congruence associated both brands. Signaling theory postulates that brands might allow consumers know the quality of their experienced products. This affects brand attitude and brand relationship toward both brands as empirically proved in this research. Consumer’s image congruence level (brand attitude/brand relationship) for a product having two high brand awareness (High-High) brands is significantly greater than consumer’s image congruence for the same product having two different brand awareness (High-Low or Low-High) brands. Consumer’s image congruence level (brand attitude/ brand relationship) for a product having two high brand awareness (High-High) brands is significantly greater than consumer’s image congruence for the same products having two low brand awareness (Low-Low) brands.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation (71172128).

REFERENCES

|

Aaker DA, Keller LL (1990). Consumer evaluations of brand extensions. J. Market. 54(1):27-41.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Aaker DA (1991). Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing the Value of a Brand Name. The Free Press, New York.

|

|

|

|

|

Aaker DA (1996). Measuring Brand Equity across products and markets. Calif. Manage. Rev. 38(3):102-120.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Aaker J, Fournier S, Brasel SA (2004). When good brands do bad. J. Consum. Res. 31(1):1-16.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Beggan JK (1992). On the social nature of nonsocial perception: The mere ownership effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 62:229-237.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Birdwell AE (1968). A study of influence of image congruence on consumer choice. J. Bus. 4:76-88.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Blackston M (1992). Observations: Building brand equity by managing the brand's relationships. J. Advert. Res. 32:79-83.

|

|

|

|

|

Carpenter P (1994). Some co-branding caveats to obey. Market News, 28(23):4

|

|

|

|

|

Clark T (1990). International Marketing and National Character: A Review and Proposal for an Integrative Theory. J. Market. 10:66-79.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dawar N, Phillip P (1994). Marketing Universal: Consumers' Use of Brand Name, Price, Physical Appearance, and Retailer Reputation as signals of Product Quality. J. Consum. Res. 58:81-95.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Debasmita B, Arijit M (2014). Optimal contract under brand name collaboration. Econ. Modeling, 37:238-240.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dolich IJ (1969). Congruence relationships between self images and product brands. J. Market. Res. 6(1):80-84.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Evard Y, Aurier P (1996). Identification and validation of the components of the person–object relationship. J. Bus. Res. 37:127-134.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Erdem T, Swait J (2004). Brand credibility, brand consideration and choice. J. Consum. Res. 31:191-198.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ericksen MK (1996). Using self-congruity and ideal congruity to predict purchase intention: A European perspective. J. Euro-Market. 6(1):41-56.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fournier S (1998). Consumers and their brand: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 24:343-373.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Graham JL, Dong KK, Chi-Yuan L (1988). Exploration of negotiation Behaviors in Ten Foreign Cultures Using a Model Developed in the United States. Manage. Sci. 40:72-95.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Grubb E, Grathwohl H (1967). Consumer self-concept, symbolism and market behavior: a theoretical approach. J. Market. 31:7-22.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Graeff TR (1996). Using promotional messages to manage the effects of brand and self-image on brand evaluations. J. Consum. Market. 13(3):4-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hamel G, Doz YL, Prahalad CK (1989). Collaborate with your competitors and win. Harv. Bus. Rev. 67(1):133-139.

|

|

|

|

|

Heath AP, Scott D (1998). The self-concept and image congruence hypothesis. Eur. J. Market. 32(11/12):1110-1123.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hoyer WD (1984). An Examination of Consumer Decision Making for a Common Repeat Product. J. Consum. Res. 11: 822-829.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hoyer WD, Brown SP (1990). Effects of brand awareness on choice for a common, repeat-purchase product. J. Consum. Res. 17:141-148.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Janiszewski C (1988). Preconscious Processing Effects: The Independence of Attitude Formation and Conscious Thought. J. Consum. Res. 15:199-209.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Keller KL (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Market. 57:1-22.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Keller KL (2001). Building customer-based brand equity. Market. Manage. 10:14-19.

|

|

|

|

|

Kressmann F, Sirgy MJ, Herrmann A, Huber F, Huber S, Lee DJ (2006). Direct and indirect effects of self-image congruence on brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 59:955-964.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Laurent G, Kapferer J, Roussel F (1995). The underlying structure of brand awareness scores. Market. Sci. 14(3):170-179.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Levy H, Lazarovich-Porat E (1995). Signaling theory and risk perception: An experimental study. J. Econ. Bus. 47:39-56.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Levin AM, Davis JC, Levin IP (1996). Theoretical and empirical linkages between consumers' responses to different branding strategies. In K. Corfman & J. Lynch (Eds.), Adv. Consum. Res. 23:296-300.

|

|

|

|

|

Levin AM (2002). Contrast and assimilation processes in consumers' evaluations of dual brands. J. Bus. Psychol. 17(1):145-154.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Macdonald E, Sharp B (2003). Management perceptions of the importance of brand awareness as an indication of advertising effectiveness. Market. Bullet. 14(1):1-11.

|

|

|

|

|

Motion J, Leitch S, Brodie R (2003). Equity in corporate co-branding. Eur. J. Market. 37(7):1080-1094.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nunnally J, Bernstein IJ (1994). Psychometric Theory, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

|

|

|

|

|

Park CW, Jun SY, Shocker AD (1996). Composite branding alliances: An investigation of extension and feedback effects. J. Market. Res. 33:453-466.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Paul FN, Stephen FD, Patrick DL (2003). When two brands are better than one. Outlook, 1:16-19.

|

|

|

|

|

Paulsson G (1986). Licensing industrial technology to developing countries: the operation of Swedish firms in India. Aussenwirtschaft, 41:533-549.

|

|

|

|

|

Ralf VL, Bram VB, Evelien D (2014). Partner Selection in Brand Alliances: An Empirical Investigation of the Drivers of Brand Fit. Market. Sci. 33(4):551-566.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rao AR, Ruekert RW (1994). Brand Alliances as Signals of Product Quality, Sloan Manage. Rev. 36:87-97.

|

|

|

|

|

Shavitt S (1989). Operationalizing functional theories of attitudes. in Pratkanis, A.R., Breckler, S.J. and Greenwald, A.G. (Eds), Attitude Structure and function Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. pp. 311-338.

|

|

|

|

|

Sirgy MJ (1982). Self-Concept in Consumer Behavior: A Critical Review. J. Consum. Res. 9(12):287-300.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sirgy MJ, Samli AC, Clairborne CB (1991). Self-Congruity Versus Functional Congruity: Predictors of Consumer Behavior. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 19(4):363-375.

|

|

|

|

|

Sirgy MJ, Grewal D, Mangleburg TF, Park J, Chon K, Claiborne CB, Johar JS, Berkman H (1997). Assessing the predictive validity of two methods of measuring self-image congruence. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 25(3):229-241.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schwartz SH, Ros M (1995). Values in the west: A theoretical and empirical challenge to the individual-collectivism cultural dimension. World Psychol, 1(2):91-122.

|

|

|

|

|

Simonin BL, Ruth JA (1998). Is a Company known by the company it keeps? Assessing the spillover effects of brand alliances on consumer brand attitudes. J. Market. Res. 35(1):30-42.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Stavros PK, Natalia R, Debra R, Jaywant S (2012).The differential impact of brand equity on B2B co-branding. J. Bus. Ind. Market. 27(8):623-634.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sugata M, Hamid B, Tarun K (2007). Brand name collaboration and optimal tariff. Econ. Modeling, 24:636-647.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Voss K, Gammoh BS (2004). Building Brands through Brand Alliances: Does A Second Ally Help? Market. Lett. 15(2/3):147-159.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wallendorf M, Arnould EJ (1988). My favourite things: A cross-cultural inquiry into object attachment, possessiveness, and social linkage, J. Consum. Res. 14(3):531-547.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wyner GA (1999). Customer relationship management. Market. Res. 11:39-41.

|

|

|

|

|

Yoo B, Donthu N, Lee S (2000). An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 28(2):197-213.

Crossref

|

|