Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

The focus of this study was to understand the impact of culture on consumer decision-making for smallholder farmers in the Murewa district in Zimbabwe. The study relied on a mixed methodology while data were collected using a survey and key informant interviews. This study found that the culture of smallholder farmers has a predictive impact on their consumer decision-making styles. In addition, culture was revealed to be a source of power to cultural gatekeepers who can influence consumer decisions within the smallholder farming community. The study's findings were that smallholder farmers in the Murewa district use four main consumer decision-making styles. These are brand-conscious, novelty-fashion-conscious, recreational-hedonistic, and habitual-brand loyal. The study concluded that the culture of smallholder farmers has a predictive impact on their consumer decision-making styles. These are brand-conscious, novelty-fashion-conscious, recreational-hedonistic, and habitual-brand loyal. The study concluded that the culture of smallholder farmers has a predictive impact on their consumer decision-making styles. In addition, culture was revealed to be a source of power to cultural gatekeepers who can influence consumer decisions within the smallholder farming community. The study recommends that community cultural gatekeepers be used to strengthen consumer education among smallholder farmers to eliminate misinformation by manufacturers.

Key words: Culture, consumer decision-making, smallholder farmers, Murewa, Zimbabwe.

INTRODUCTION

Zimbabweans and particularly smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe, perform several transactions to purchase goods and services, particularly in agriculture such as at their nearest agro-dealer, or major agricultural retailer. These farmers as consumers play an integral role in any business by creating demand for goods and services leading to the growth of a business and ultimately increasing shareholder value through profitability (Yee and Hooi, 2011). With the entry of several competing providers of goods and services, the consumer decision-making process has become more complicated than before. Consumer behavior is activated by needs (Cant et al., 2006) which are influenced by factors such as lifestyle, personality, demographics, friends, status, situations, and culture- all of which influence choice in purchase to satisfy a consumer need (Babin and Harris, 2012).

Research has shown that culture is an influential factor as it pertains to consumer behavior, and this influence can best be assessed through consumer decision-making styles (Chen et al., 2012). However, it must be noted that Zimbabwean culture while well documented and described in literature has not had an impact on consumer behavior. Consumer decision-making styles, while having strong ties to purchase behavior and sales, are important because they provide a useful operationalization of consumer behavior. This is due to their stability over time. Thus they are useful to segment a market. Consumer decision-making styles are critical in profiling consumer traits, and in particular aiding consumers with financial management (Moschis, 1976b; Mokhlis, 2009). Consumer decision-making styles are significant to strategic marketing as a firm’s marketing strategy is determined by its engagement with the consumer decision-making process (Chen et al., 2012).

Within previous research mostly in western and developed nations, it was established that culture decides what is acceptable with products. This extends to what people can and should wear, eat, reside, and where they can travel (Leng and Botelho, 2010). Culture essentially determines what people buy, how they buy and when they buy, and why they buy (Mothersbaugh and Hawkins, 2016). For example, Indian cultural values include good health, education, individualism, and freedom. Consequently, in India, it is acceptable for parents to prioritize purchasing educational books over tabloid magazines, so one can see how culture is an influencer of consumer decision-making styles (De Mooij, 2010).

While there has been significant research in defining the specific culture as a construct in Zimbabwe (Biri and Mutambwa, 2013) there is little documented evidence on the impact culture has on consumer behavior operationalized as decision-making styles. Studies by De Mooij (2010) indicated that culture has an impact on consumer decision-making styles, the specific nature of the impact is unknown and thus warrants further study and provided a necessity for this study.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Presently, two different models form the theoretical underpinning of this study. The two theories that formed the basis of this study are Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory which is modeled through the 6-D model of National Cultures (Hofstede, 1980), and the Consumer Styles Inventory Eight-Factor Model (Sproles and Kendall, 1986).

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions Model/6-D model of national culture

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions framework is the most widely used within the social sciences and business to operationalize culture. Over two decades, Hofstede had access to IBM’s over 100,000 Employees in over 70 countries.

He distributed 116,000 survey questionnaires and the responses caused him to realize that there were dimensions common to cultures across geographical spaces. He initially discovered four, and through further research discovered two more dimensions linked to geographic, demographic, and political characteristics of any given society. Thus Hofstede discovered that cultures take on the personality of their countries and have varying scores within each of the six dimensions as guided by the earlier stated personality. Hofstede’s model thus classifies cultural values and practices into the dimensions below through which cultures can be measured and compared one to another.

i) Power Distance Index (PDI)

This dimension is focused on the different solutions to the basic problem of Human Inequality, where those individuals who have a close relationship with leaders or persons in power have greater social equity than those who are further from the throes of power (Hofstede, 2011).

ii) Uncertainty Avoidance (UA)

This dimension expresses the degree of stress in a society in the face of an unknown future, where higher scores reflect risk aversion in a culture, while lower risk relates to a greater predilection to risk (Hofstede, 2011).

iii) Individualism versus Collectivism (IDV)

This standard relates to the cultural standard integration of individuals into primary groups, where individualist cultures would consider the individual as the basic economic and social unit and hold this unity in high value, whereas collective cultures would consider the basic group would consider the smallest relative group as the basic economic or social unit held in high value (Hofstede, 2011).

iv) Masculinity versus Feminism (MAS)

This relates to the division of emotional and societal roles between men and women, where high-scoring nations are patriarchal, and low-scoring nations are more equitable (Hofstede, 2011).

v) Long-term versus Short-term Orientation (LTO)

This dimension relates to the degree of focus of human effort, be it the future, the present, or the past(Hofstede, 2011).

vi) Indulgence versus Restraint (IVR)

This dimension pertains to the gratification versus control of basic human desires as it relates to enjoying life, where high-scoring cultures would prioritize instant gratification vis-à-vis, ‘you only live once, and low-scoring cultures would work towards self-control for delayed gratification, as would be summarised by the idiom, ‘work now, play later (Hofstede, 2011).

While his empirical results broadly concurred with Inkeles and Levinson’s (1969) study, due to the exploratory nature of Hofstede’s work, the results were reliable, easier to interpret, and went beyond any personal preconceptions to initially establish four dimensions of culture and through validation across several contexts in over 70 countries to add two more for a total of 6 dimensions of culture (Hofstede and Minkov, 2010; Minkov and Hofstede, 2011).

One criticism of Hofstede’s work in culture studies is that he applied a universalist approach and assumed that the values are equal across contexts. However, Hofstede’s theory has since been culturally validated across several countries in the world, including many on the African continent (Oppong, 2013; Rarick et al. 2013). Another challenge to Hofstede’s is that it assumes that nation and culture are synonymous, which fundamentally returns this study to the issue of generalization of western cultures to the world, ignoring the nuances that context provides. For example, while there is one official language in the United States, there are sixteen official languages in Zimbabwe and several tribes each with its customs unique to themselves. This study’s perspective concurs with Baskerville (2003) who found that Hofstede’s methodology failed him in that he used nations as his basic unit of analysis and not culture per se. Thus Hofstede’s model seems to address geographies more than it does social groups.

The profile of consumer style: Eight factor model

The Profile of Consumer Style: Eight-Factor Model (PCS) is the theory that holds the framework of consumer decision-making styles. This is done through an 8-factor model known as the Consumer Styles Inventory. Three leading theories that lay the foundation for this theory are the psychographic/lifestyle approach, the consumer typology approach, and the consumer characteristic approach. The psychographic approach identified over 100 characteristics founded on cognitive thought patterns, that are relevant to consumer behavior (Wells, 1974; Lastovicka, 1982). Some of these characteristics are closely related to consumer choices while others relate to general lifestyle activities or interests.

These psychographic approaches successfully identified the traits relevant to consumer behavior, but they failed to identify a standard, or categories by which styles can be identified and compared for respondents,one to another.

By contrast, the consumer typology approach attempted to define general consumer typologies, known as patronage strategies, and orientations (Stephenson and Willet, 1969; Darden and Ashton, 1974; Moschis, 1976a). However, it failed to capture the behavioral element that is rooted in the psychological element of consumer behavior. With continued research development the consumer characteristics approach sought to develop a more cognitive and affective learning approach, directed toward capturing consumer characteristics understood from a psychological perspective as they were related to purely consumer decision-making (Sproles, 1979).

As further consumer-behaviour-related studies investigated and attempted to measure and comparatively categorize consumer behavior, Sproles and Kendall (1986) consolidated the psychographics, consumer typology, and consumer characteristic approaches to develop a model that successfully consolidated the anthropological, psychological, and marketing elements of consumer behavior. Consequently, the new model, known as the Profile of Consumer Style: Eight-Factor Model (PCS) successfully realized that consumer behavior while difficult to measure can be operationalized through what Sproles and Kendall (1986) conceptualized as consumer decision-making styles. Consumer decision-making styles can be defined as a mental orientation characterizing a consumer’s approach to making choices. These consumer decision-making styles offer the advantage of having the ability to be empirically measured and allow for one person or one group’s style to be compared to another.

The instrument used to measure one’s profile was known as the Consumer Style Inventory (CSI) (Sproles and Kendall, 1986). Each tested individual’s style was a combination of scores across each of the eight factors that were combined and scored to be the Profile of Consumer Style (PCS). The factors could exist in any combination to constitute a PCS. However, there would be a dominant style. The factors are listed and explained below.

i) Perfectionism or high-quality consciousness

Items loaded for this factor assess a consumer's search for the highest integrity in product quality.

ii) Brand consciousness

This characteristic measures consumer orientation towards purchasing more expensive, popular brands. Consumers with high scores in this category believe that a higher price equates to higher quality.

iii) Novelty-fashion consciousness

This characteristic relates to fashion consciousness and novelty consciousness as well. High scorers are likely to show excitement and obtain pleasure from seeking out new things.

iv) Recreational and hedonistic shopping consciousness

High scorers within this characteristic enjoy shopping and participate in the activity for the pleasure they clean from it.

v) Price consciousness

This is the “value for money” characteristic. Those scoring high would look for sale prices and are conscious of lower prices in general.

vi) Impulsive careless orientation

This factor pertains to measuring the impulsivity of the purchase pattern. High scorers on this characteristic do not plan their purchase habits.

vii) Confused by over-choice consumer orientation

High scorers within this characteristic perceive the variety of brands and stores from which to purchase. However, they will have difficulty making a choice.

viii) Habitual, brand-loyal consumer orientation

High-scorers with this characteristic are most likely to have preferred brands and stores and will have formed supporting habits in choosing these.

This study builds upon the PCS for two significant reasons. The first is that the CSI instrument has been applied and proven consistent and accurate across several contexts in several countries and has been argued to be the most widely used framework for assessing decision-making styles among consumers. It has been used consistently since 1986 in countries such as China, South Africa, the United States of America, and Europe (Bakewell and Mitchell, 2006; Bauer, Sauer and Becker, 2006; Radder, Li, and Pietersen, 2006; Leng and Botelho, 2010; Zhang et al. 2013)..

Secondly, the PCS was the pioneering theory that elaborated on the consumer characteristics approach toward understanding consumer behavior. It was intended to serve the interest of marketing professionals with an interest in consumer behavior. Also, it is widely used to segment markets, making it a seminal work for studying decision-making behavior in different contexts, the instrument has demonstrated its consistency and accuracy in measuring and classifying consumer decision-making styles, and so it was the best tool available to measure consumer decision-making styles among smallholder farmers in Murewa.

Underpinning concepts of the study

Having understood the underlying theories within the discussion of this study, there are several concepts that the study could focus on. However, most pertinent to this study are two concepts: culture and consumer decision-making styles. It is the interaction of these concepts at both a theoretical level and in practical application for business and academia that has necessitated this study.

Culture

Culture is a construct that has been defined in different ways. Hofstede (2011) defines culture as ‘the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category from others’. This is a simple definition that captures the psychological perspective of culture. It goes beyond the social development perspective of culture which is captured in Kluckhohn’s definition. In his definition of culture, Kluckhohn (1951a) noted that culture, consists of patterned ways of thinking, feeling, and reacting, acquired and transmitted mainly by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievements of human groups that includes their embodiment in artifacts; the essential core of culture consists of traditional ideas and their attached values. Consequently, this study builds its definition on the foundation of Kluckhohn’s seminal work, and captures the perspective of Hofstede.

Thus for this study, culture is the set of values ideas, and attitudes developed over time, shared, and accepted by a homogenous group of people and transmitted to the next generation. The passage of culture from one generation to another is missing from Hofstede and Kluckhohn’s definitions, but is critically important to the understanding of culture, particularly within the African context where this generational transfer is a key characteristic (Ndlovu and Dube, 2012).

While Hofstede’s definition captures an additional dimension, the psychological perspective is valuable to this study as it has a specific characteristic of the concept of culture that Hofstede does not address adequately. This is because culture is used as a sense-making tool. Kluckhohn (1951a), while writing his seminal text that explores human cultures, argues for the development of universal classes of culture, this is because while the definition of culture is universal and regarded as universalizable, the cultures themselves in their practiced-state cannot objectively and empirically be categorized, measured and compared. This is because as Kluckhohn (1951) argued, cultures constitute several and varying solutions to common problems to questions that universally exist across people groups.

There have been several approaches used to identify and operationalize culture. This is because culture is broad and too global to be meaningful as an explanatory variable without being operationalized (Lenartowicz and Roth, 2001). Therefore cultural studies may be inferential. However, through Hofstede’s work, culture was operationalized through his six dimensions theory and his research survey-questionnaire instrument known as the Values Survey Module-2013 (VSM-2013) (Hofstede, 1980, 2013). Through this instrument, culture can be measured within this study, and specific aspects and their unique influence on variance in the dependent variable assessed. For example in other studies, the power-distance dimension was seen to affect advertising appeals in consumer behavior (Albers-Miller and Gelb, 2001).

Hence the use of Hofstede’s theory and research instruments, the 6D Cultural Framework, and the Values Survey Module (Hofstede, 1980, 2013).

Consumer behaviour and consumer decision-making style

Consumer behavior is a multi-disciplinarian field of study that includes aspects of Psychology, Anthropology, Psychology, and Marketing. It is defined as the process involved when people select, purchase, use or dispose of products, services ideas, or experiences to satisfy needs, and desires. Consumer behavior can be viewed as a process that factors in issues that affect the consumer before, during, and after a purchase (Mothersbaugh and Hawkins, 2016).

Theories of consumer behavior are firmly rooted in Western Psychology that are foundationally limited in their scope, and empirical research to a small area of the Western hemisphere (De Mooij, 2019). When studying consumer behavior, there existed a need to categorize and measure this behavior to an empirically valid and reliable standard. To that end, Sproles and Kendall (1986) successfully operationalized Consumer Behaviour with the PCS. This methodology developed by Sproles and Kendall (1986) conceptualized and measured consumer behavior through eight factors of consumer decision-making.

In their analysis of culture and its interaction with consumer behavior, Albers and Gelb (2001) found that there are specific dimensions of culture that interact uniquely with certain aspects of consumer behavior. They found that the power-distance dimension affects the advertising appeal aspect of consumer behavior speaking to the perspiration of aspiration being influenced by one’s distance from a position of influence and privilege among the 11 countries they surveyed. However, the challenge faced by such early studies is that they lacked the operationalization of the concept of consumer behavior through a theory and model like the Consumer Style Inventory: eight-factor model. There have been studies that added this operationalization, such as that by Mafini and Dhurup (2014). This study added robustness and detail to the detail of the study, more than Albers and Gelb had experienced. Thus this helped them analyze the variance in each factor of the consumer decision-making styles that was linked to scores in each of Hofstede’s six dimensions. While their study was robust it was broad in terms of the sample size. This study focuses, on a specific segment in a specific location that has previously been unexplored for this study. This study offers new knowledge specifically to those business marketing to smallholder farmers, and smallholder farmers themselves who become the beneficiaries of value as consumers.

It must be noted that the predictive value of culture towards consumer behavior is not a best practice. This is because studies that focus on cultural values as predictors assume that societies are static and independent of each other (Briley, 2009). Thus while this study acknowledges there may be some predictive value within this study, the focus of this study is not predictive, but more explanatory investigating how culture explains variances in consumer behavior as manifest through consumer decision-making styles.

In Mokhlis’ (2009) study on consumer behavior and culture, it is important to note that Consumer Decision-Making Styles and Hofstede’s cultural framework are not paired together. This is because consumer behavior was the concern of this study. The same is observable in the work of Ercis et al. (2006). This is telling of how culture in these studies is regarded conceptually at a broad and global level. This is an important distinction between this study and previous studies is the more granular nature of this study to investigate culture as a whole and how each cultural dimension interacts with each factor of consumer decision-making style. This granular detail is an important contribution this study makes to new knowledge within the subject matter.

Considering that neither national culture nor consumer behavior data for Zimbabwe are available, one must question the cross-cultural validity of both Hofstede's (2013) and Sproles and Kendall’s (1986) instruments. This question and criticism of the validity of the cultural and consumer behavior instruments are rooted in the fact that many of these theories are developed in the west and assumed to be generalizable to the rest of the world. Indeed, participants in 96% of studies are members of communities that comprise only 12% of the planet’s population (Berry, 2015). Yet, the theories developed from these studies are considered universally valid (Glebkin, 2015). Thus the question arises as to whether Hofstede's (2017) Kendall and Sproles’ (1986) works were consistent and accurate for use on the African continent. As has been established above, Zimbabwe’s national culture is yet to be profiled in such a way that it can be observed, explained, and compared to other cultures (Hofstede, 2017), on an even plane.

In addition to this, while the predictive, deterministic, and explanatory ability of culture toward consumer behavior has been determined in previous studies, and theoretically can be generalized to Zimbabwe, the specific direction or the specific nature of the effect of culture on consumer behavior has not been determined. With this background, this study is relevant to establishing the exact nature of the relationship between culture and consumer behavior.

METHODOLOGY

This study relied on a mixed methodology. This methodology sought, not just to test a hypothesis for adherence to existing theories which would have justified a quantitative study, but to explain the interaction between culture and consumer decision-making styles, which required this research study’s participants to elaborate on their responses to the CSI (Leedy and Ormrod, 2016) through the use of qualitative methods. The simple random sampling technique was used to select 60 participants for the study. Key participants were drawn from government officials from the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Water, Climate and Rural Resources, one agricultural supplies dealer (agro-dealer) working within Murewa District, one representative each from agricultural input manufacturers, and twelve smallholder farmers. The purposive sampling technique was used to key participants who could provide insights into the quantitative results through their unique perspectives and relationship with the target population (Somekh and Lewin, 2005).

Secondary data included peer-reviewed journals, newspapers and websites, biographies, censuses, books, and databases (Trochim and Donnelly, 2008). Secondary data was valuable in cases where primary data was difficult to obtain and unavailable such as the unavailability of consumer decision-making style profiles among retailers for small-scale farmers. In analyzing the data, this study utilized the International Business Machine’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) a robust quantitative statistical data analysis software package. Using this tool the first step was to establish the reliability of each scale using Cronbach’s (1951) alpha coefficient.

PRESENTATION AND DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

This section presents the key findings of the study.

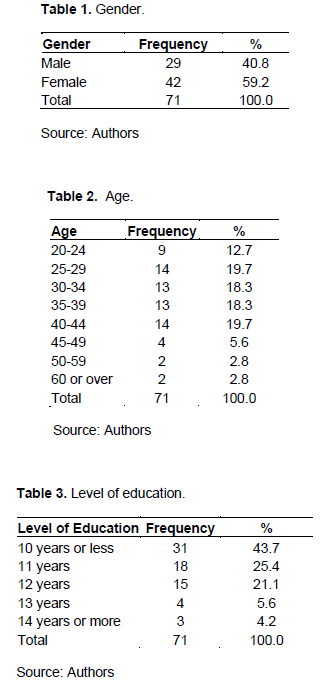

Gender

Within this study, there were a total of 71 participants and among whom the majority (57.7%) were female while the minority (42.3%) were male. This demonstrates that women are dominant among smallholder farmers. This gender skew is consistent with prior research. Especially, considering how home-based farming which encompasses smallholder farming is seen as a home-based industry among African nations (Food and Agriculture Organisation, 2018) (Table 1).

Age

The age distribution in this study is slightly skewed toward the young with 69.01% (N=49) of respondents being between the ages of 20-39, while 30.99% (N= 22) were aged 40 and above. This demonstrates a high skew toward having young people within the productive sector among smallholder farmers in Murewa. This supports the position that developing countries will have a high proportion of young people in productive sectors compared to older persons, without transitioning the older individuals towards retirement (Bloom and Freeman, 1986; United Nations, 2020). This also matches the pattern of the population curve within the last national census within Zimbabwe and of course Murewa (Zimbabwe National Statistic Agency, 2012) (Table 2).

Education

Of the total number of participants (N=71), 69 (97.18%) of the participants demonstrated literacy, with only 2 (2.82%) participants requiring assistance to complete the quantitative survey questionnaire. This was due to health complications. In summary, 43.7% of participants reported 10 years or less of education, while only 25.4 reported having completed 11 years of education which is the equivalent of the Ordinary Level General Certificate of Education. Only 4.2% of participants in this study reported having university-level, tertiary education. The demographic findings summarised above are presented in tabular form below. It is important to recognize that literacy may compromise decision-making as previous studies have shown that individuals showing low literacy are more dependent on shop floor staff for consumer guidance, due to their limited efficacy in reading and understanding wrote product information (Van Staden and Van Der Merwe, 2017). As such low-literacy individuals were excluded from this study. Table 3 show the level of education.

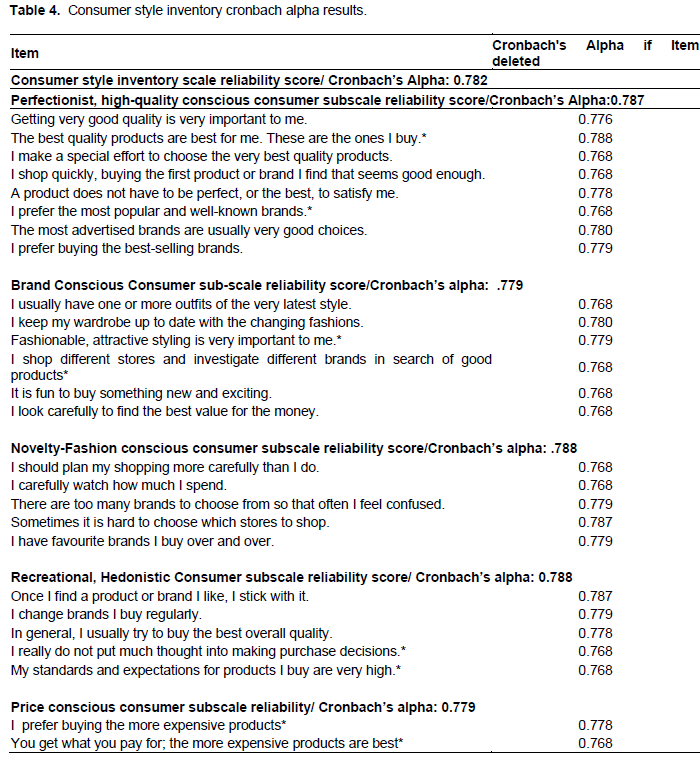

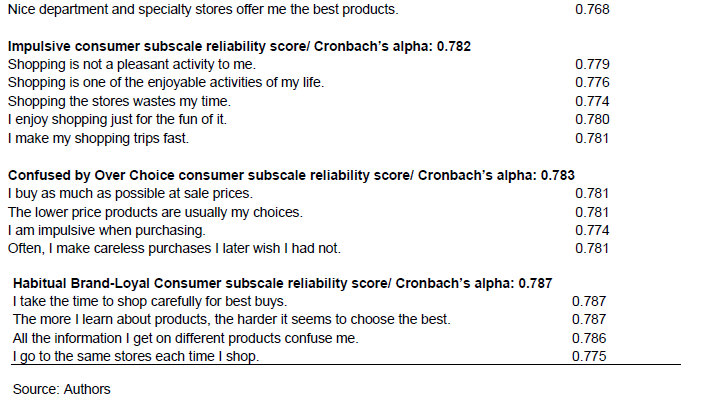

The reliability analysis of the Consumer style inventory measuring consumer decision-making style is summarised below. Items that would have decreased the cumulative reliability score below the acceptable threshold of 0.700 during the pre-test for the scale were deleted and recoded. These are marked in Table 4 by an asterisk.

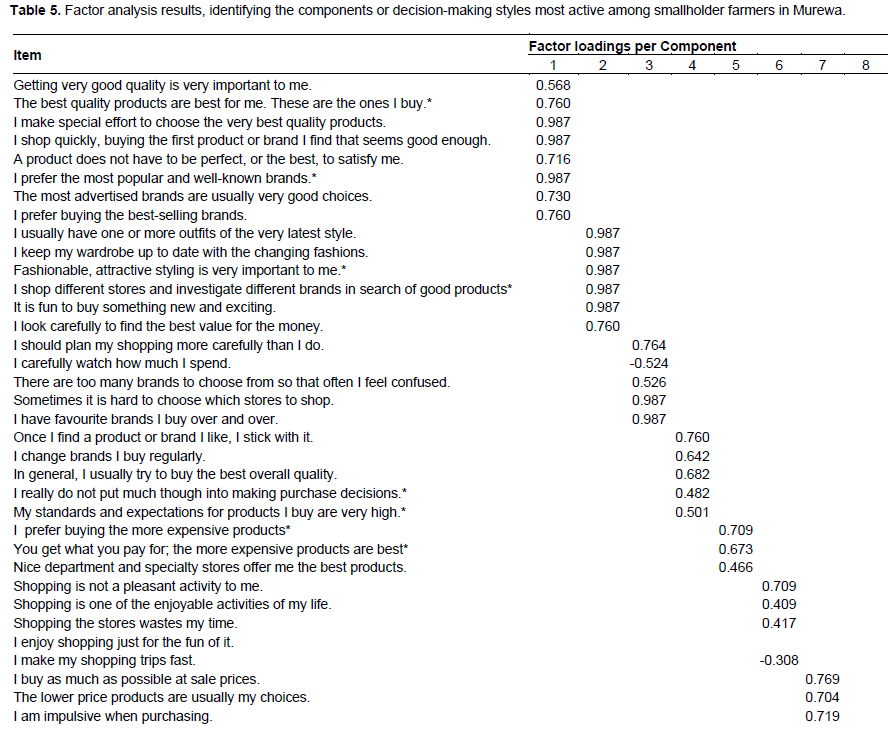

Exploratory factor analysis

An exploratory factor analysis was carried out using the Principal Components Analysis method. Initially, the factorability of the items within this scale was assessed. Firstly, this study noted that all 40 items correlated with at least another item in the instrument by r2=.3 which, in itself, suggested factorability. Secondly, Bartlett’s test of sphericity, which assessed the significance of the interactions within the correlation matrix was significant (x2(153)=593.927, p<.001). Lastly, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy which assesses the sample’s adequacy to the strength of the instrument scored at 0.589 which is above the threshold of significance (KMO=0.5) (Bryman, 2008). Having satisfied these benchmarks, factor analysis was feasible to analyze. To ensure orthogonal data and eliminate multicollinearity, the variance maximization rotation method, also known as varimax was used. This method simplifies the factor loadings of each item by removing the clutter of shared variances and identifying the factor within which the most variance is accumulated (Somekh and Lewin, 2005).

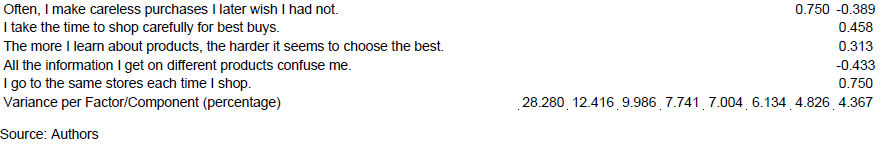

The study also sought to establish the consumer decision-making styles at work among smallholder farmers in Murewa using the Eight factors identified by (Sproles and Kendall, 1986). The factors accounted for 80.755% of all variance among the items. The decision styles at work among smallholder farmers in Murewa were confirmed to be (1) perfectionism, or high-quality consciousness, (2) brand consciousness, (2) novelty-fashion consciousness, (3) recreational, (4) hedonistic shopping consciousness, (5) prince consciousness, (6) impulsiveness, (7) confusion with over choice, and (8) brand-loyal consumption. These factors and their detailed correlated factor loadings per component are detailed below. It is important to note that these results validate similar previous empirical studies (Sproles and Kendall, 1986; Canabal, 2002; Radder et al., 2006; Mafini and Dhurup, 2014). Table 5 show the factor analysis results, identifying the components or decision-making styles most active among smallholder farmers in Murewa.

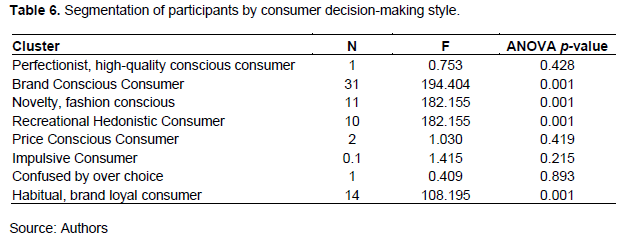

While the principal components analysis identified which consumer decision-making styles were active among smallholder farmers, it was necessary to segment the participants to observe how many participants belonged to each decision-making style. As such a K-means cluster analysis was used to classify the smallholder farmers within the sample according to their decision-making styles. This analysis calculated the mean values for each factor or consumer decision-making style. The K-means cluster realized 8 homogenous segments, with each segment representing the active consumer decision-making style. However, only four of these segments were significantly above the threshold of error (p<.05). Thus one will note that there are five segments of smallholder farmers that each has a single dominant consumer decision-making style in Murewa. The results of the K-means cluster analysis are presented in Table 6.

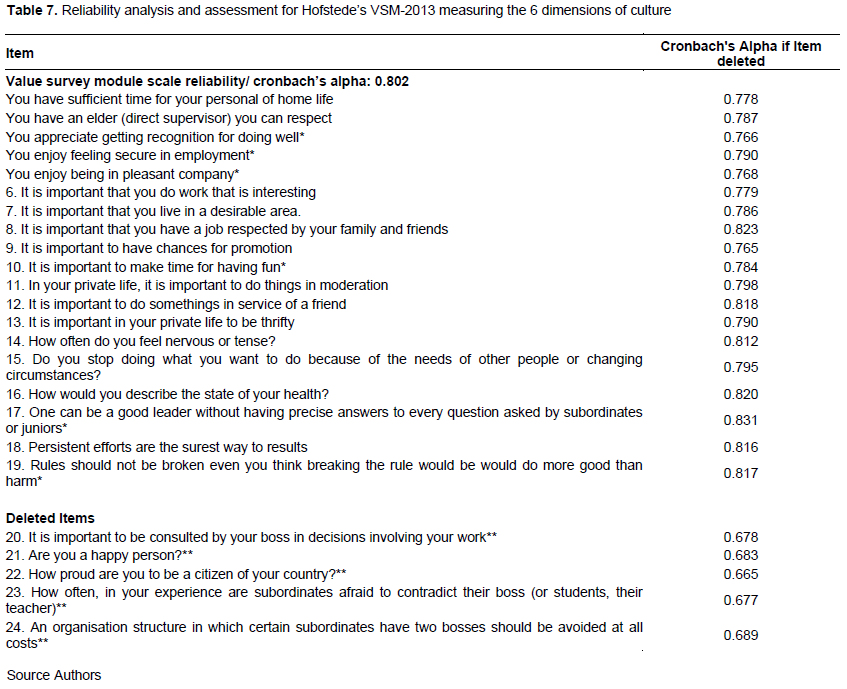

Assessing the reliability of the values survey module

The same measure of reliability was applied to the investigation of the 6 dimensions of culture using the VSM-2013 instrument as was applied to the CSI. The Cronbach alpha scores are detailed in Table 7. Twelve items scored below the Cronbach alpha threshold in the pilot study. These were re-coded for relevance and consistency and marked within the table with an asterisk. Of these twelve, however, five items were continuously scoring low on the Cronbach alpha coefficient and so these are marked with a double asterisk. These items were then excluded from further analysis.

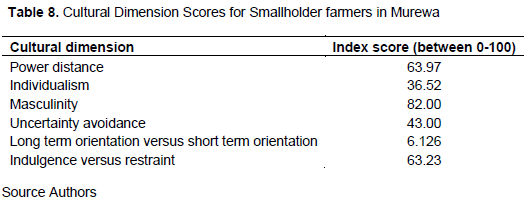

Calculating Murewa smallholder farmers cultural index scores

The study also sought to discover the culture at work among smallholder farmers in Murewa. It is important to remember that culture is a construct within a group (Kluckhohn, 1951b, 1951a), and while there maybe individual cultural preferences and leanings. This study concerns itself with the culture of the group of smallholder farmers in Murewa (Hofstede et al. 2010; Hofstede, 2013), and the values survey module was designed to measure the cultural dimensions of the group. Within the manual for the values survey module, there are prescribed formulas to assess the cultural profile for this group of participants who are smallholder farmers in Murewa (Hofstede, 2013). These are listed in Table 8 along with the index score for each dimension of culture, to identify the culture at work among smallholder farmers in Murewa.

Relationship between culture on consumer decision making styles

Having measured consumer decision-making behavior and culture as separate constructs, the research necessitated that the nature of the relationship between the two is investigated. Due to the multivariate nature of the constructs, both have multiple components (eight factors of consumer decision-making style, and 6 dimensions of culture). A multivariate Analysis of Variance test was conducted to determine whether culture explained consumer decision-making styles among smallholder farmers in Murewa. It was hypothesized that culture would indeed have an impact on the consumer decision-making style among smallholder farmers. The results showed that the multivariate statistic was not statistically significant to affirm culture’s ability to causally affect consumer decision-making styles (F(32,219.176)=1.246, p<0.182; Wilk’s Lambda=0.540; partial eta squared=0.143).

As affirmed above, this study established that there was no causal relationship between culture and consumer decision-making styles among smallholder farmers in Murewa. This did not translate to mean that culture did not have an impact on consumer decision-making styles among smallholder farmers in Murewa. Culture could making style. Thus a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to assess whether culture and specifically the dimensions of Power-Distance, Individualism, Masculinity, Uncertainty-Avoidance, Long Term Orientation versus Short Term Orientation, and Indulgence vs Restraint, had the predictive ability as it pertains to consumer decision-making styles. These variables, to the point of statistical significance, successfully predicted consumer decision-making styles among smallholder farmers in Murewa F(6,64)=2.343,p<0.042, R2=0.624.

The strength of prediction per dimension of culture is statistically significant as is summarised in the table below, thus proving the alternative hypothesis that culture has a statistically significant impact on consumer decision-making style, albeit a predictive one and not a causative one.

Meaning of culture among smallholder farmers and stakeholders

When inquiring as to the meaning of culture, it was peculiar to note that culture had a different meaning between stakeholders and the farmers themselves. Two of the three stakeholders reported that culture is a hindrance within their personal lives, with an agricultural input manufacturer reporting that,

Culture refers to a way of life in this community, but for me, it refers to a pattern of communication, that can facilitate entry into the community.

Among the smallholder farmers themselves, it seems that culture was identified as a source of power for certain types of people, with 73.333% of participants (N=11) identifying that culture gave men, and elders of a certain power to make decisions, for their families and community, when asked two questions. The first being, “Who makes decisions in your household?” and the second question, following up on the request to identify cultural gatekeepers and resources persons asked, “How would you respond to this resource person providing consumer guidance that discredited the consumer advice to a smallholder farmer?”

It is peculiar to note that culture among the smallholder farmers had a shared meaning. However, the smallholder farmers did not necessarily identify the role of culture within their community of smallholder farmers. Rather, they would point to what this study can identify as markers of the role of culture, or instances of culture at work, with a smallholder farmer indicating that:

Most Elders in this community command a lot of respect due to their age and experience which has helped members of this community.

This points to the role of culture to respect the elders within the community due to their experience. Also, one smallholder farmer mentioned that:

In our culture, we respect whoever has the title of Chief, and if they tell us this product is not good for us, the Chief must know better than us, because he goes to places, we don’t go.

Lastly, another of the smallholder farmers who have been identified as a cultural gatekeeper said another of the following concerning their motivation for improving their farming skills.

For me, my efforts are focused on being a better farmer. And, I have realized that if I am a better farmer, I can help my fellow farmers be better, and they can help me be better. So I reach out to them and they reach out to me as well.

These sentiments were shared by 66.67% of participants (N=10) who demonstrated that smallholder farmers recognize and appreciate the role of culture, even if they cannot articulate it specifically as being a cultural phenomenon. An Agrodealer indicated that:

Within my personal life, I do not see it (the relevance of culture), but in our work, the traditional Shona culture is important, especially in helping us understand and work with smallholder farmers. I remember this field day, where, because of resource issues we neglected to buy a gift for the local headman. We had a successful time, but we did not recover any sales from our investment until we met the community cultural leaders and made amends.

Influencers of purchase decisions

When asked to identify the influencers of purchase decisions, there were two significant indications in responses. 60% (N=9) of all respondents identified two shared influences of purchase decisions, which are government and community gatekeepers. The Agricultural Extension Officer noted the following.

I have noticed that my position as a government officer helps the people trust that I am trying to help them. There is a level of power or authority that my job gives me not to tell people what to do, but it helps them know that I am a good source of information because we get the newest information from the government labs.

While an agricultural inputs manufacturer noted the following:

Smallholder farmers also make decisions influenced by cultural and traditional leaders, but I don’t think they know that consciously, but culture is a significant influence.

The identification of government officials and community gatekeepers as sources of information is understandable for this target population when considering the high power-distance (PDI=63.97) and low individualism scores (IDV=36.52) which reflect high trust and high communal herd-mentality type values in which individuals prefer to be members of the group rather than acting and functioning in solitude which supports previous studies (Briley, 2009; Kamaruddin, 2009).

Basis of trust

The study found that there was a level of trust between smallholder farmers, cultural gatekeepers, and government officials. One key participant supported this by saying:

We are each other’s tools as fellow farmers and colleagues.

This reflects the low individualism of the community of farmers. While for government officials, one responded in the following manner,

We trust the government. They know best and for them to send someone here (Agricultural Extension Officer), shows that she is good at her job.

This is further evidence of the high power-distance score and provides an elaboration of why this score exists; that positions of authority are revered and assumed to have the smallholder farmers’ best interests at heart.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that the culture at work in the Murewa district consists of all six of Hofstede’s dimensions. Of particular interest is how the aggregated Masculinity Index score (MAS=82.00) is quite high. While this study was looking at the active culture within the workspace of smallholder farmers, it was interesting that Masculinity, conventionally a function of the patriarchal nature of African culture particularly within the domestic space was high (Oppong, 2013; Mwale and Dodo, 2017). This demonstrates, that in the same way that gender roles grant men authority in the domestic space, men due to their gender are expected to take leadership. Consequently, within this study, among smallholder farmers in Murewa, men are held in high regard, even without having significant experience. The source of this authority was discovered through qualitative analysis to be the cultural values of the Shona people in Murewa with the female participants within the qualitative portion of the study acknowledging that men play a major part as decision-makers or advisors within the consumer’s decision-making process. Thus even if a woman oversees the farm smallholding, she will consult her partner and rely on his acumen even if he is not a farmer. This supports previous research about the predisposition that places structural and cultural restrictions on women without a ‘man’s guidance’ (Manyonganise, 2015; Maunganidze, 2020). One participant said she was ‘grateful she had a husband who supported her desire to succeed’ with her farming venture.

The second dimension of Individualism versus Collectivism (IDV) also scored low (IDV=36.52). This speaks inversely to the high level of community within the culture of smallholder farmers in Murewa. Indeed, as acknowledged above, some farmers are motivated by the desire to improve the quality of crops and the communal herd, regarding the quality of the community’s crop as being ‘as strong as that of the least among us.’ This is consistent with the teaching of ‘Unhu’ and African worldview within Zimbabwe that promotes the oneness of community and decries individualism as a selfish attribute (Viriri and Viriri, 2018). This would explain why the novelty, fashion consciousness decision-making style is dominant. This decision-making style is predicted inversely by the IDV index score, and it was observed through the qualitative portion of this study that culture determines how trends are set, and who sets these trends. This study was specifically identified the cultural gatekeepers, individuals usually elder of either gender (MAS=82.00) who are custodians of culture and can give consumer guidance that can override the consumer advice of a trained professional, or buttress government policy such that it is followed. Thus cultural gatekeepers are trusted based on their tenure, and the authority that cultural values grant them, to share the knowledge that guides consumer decisions. This supports previous research that found that cultural gatekeepers were critical in knowledge sharing for the community as it pertains to improving food security and disaster resilience in another rural community in Binga, Zimbabwe (Manyena et al., 2008).

The Smallholder farmers in Murewa scored low on the Long Term versus Short Term Orientation Index (LTO=6.126). Scoring high on this index indicates a short-term orientation as it pertains to planning. In other words, regions that score high on this index, are not heavily invested in planning. This, therefore, means that smallholder farmers in Murewa are less impulsive and increasingly invested in planning, even when it comes to practices as mundane as shopping and consumer decision-making. Thus one will note that due to the low planning score, there is a single individual with an impulsive consumer decision-making style, and yet even then the presence of this decision-making style is not statistically significant. (F=1.415, p<0.215).

The LTO variable in this instance successfully predicts the lack of impulsive consumer decision-making among smallholder farmers in Murewa (Hofstede, 1980). Interestingly, the smallholder farmers do not identify this predictive relationship, they just recognize the value of planning without drawing this link to their behavior, even though other stakeholders, such as the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Water, and Rural Resettlement Officers can draw this link. This is inconsistent with previous research on indigenous knowledge systems among the Ndau people and how there is a long-term orientation to these indigenous knowledge systems (Muyambo, 2018).

Lastly, and of note is the way culture can facilitate purchase decisions based on trust. The qualitative portion of this study, while noting that the farmers themselves did not recognize this role for culture, the stakeholders who support smallholder farmers, specifically agricultural input manufacturers, agro-dealers, and agricultural extension workers (government officials). While these professionals may practice, western ethics in other facets of their business, they adapt and revere African ethics within the context of smallholder farmers in Murewa, to entice smallholder farmers to make agricultural purchase decisions.

CONCLUSIONS

This study’s findings have significant implications for businesses, governments, and smallholder farmers themselves. The fact that it was possible to segment farmers by consumer decision-making style is critical for effective marketing as it facilitates the streamlining of marketing processes, by enabling Marketing Managers to use the marketing techniques that appeal to the needs, proclivities, and inclinations of each segment as determined by the consumer decision-making style for each segment among the smallholder farmers in Murewa. This is because it was discovered that it was impossible to appeal to all types of consumers with the same type of techniques, and so Marketers would require a new approach, hence segmentation (Fonseca, 2011). Through this study though, it is possible to segment smallholder farmers in a way that is relevant to their context, as this study adapted this instrument to the needs of the local market.

Secondly, because of this study, it is now possible to predict the consumer decision-making style and segment that a smallholder will be within based on the cultural score. This information can aid governments in developing policies that speak to the needs of smallholder farmers. Also, the fact that government officers are well regarded among smallholder farmers thus places them in a position to be conduits for information dissemination of new government research and consumer education as to which products are safe and legal to use, thus adding value to government interaction with smallholder farmers. Not only would this new knowledge be valuable to the government, but the predictive value of culture is useful to for a business to identify pathways to penetrate new markets, by having the wherewithal to identify new markets, profile their culture, and predict which consumer decision-making styles are active. Through the knowledge gleaned from this study, previously inaccessible markets can now be accessed by predicting consumer decision-making styles from culture.

For smallholder farmers, the implications of this study are too clear. While culture has an impact on consumer decision-making styles of smallholder farmers in Murewa, their ability understands the role it plays was observed by stakeholders, but not perceived by them. Consequently, this study has well-placed implications to provide smallholder farmers in Murewa with information about how culture affects their consumer decision-making behavior, and thus they will be better informed to make better consumer decisions.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Albers-Miller N, Gelb B (2001). Business advertising appeals as a mirror of cultural dimensions: A study of 11 countries. Journal of Advertising 25(4):57-70. |

|

|

Babin BJ, Harris EG (2012). Consumer Behaviour. 4th edition. Mason: South-Western Cengage. |

|

|

Baskerville RF (2003). Hofstede Never Studied Culture, Accounting, Organisations and Society 28:1-14. |

|

|

Bauer HH, Sauer NE, Becker C (2006). Investigating the relationship between product involvement and consumer decision-making styles. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 5(4):345-354. |

|

|

Berry JW (2015). Global psychology: implications for cross-cultural research and management. Cross-Cultural Management 12(3):342-355. |

|

|

Bakewell C, Mitchell VW (2006). Male versus female consumer decision making styles. Journal of Business Research 59(12):1297-1300. |

|

|

Bloom DE, Freeman RB (1986). The effects of rapid population growth on labor supply and employment in developing countries. Population and Development Review 12(3):381-414. |

|

|

Biri K, Mutambwa J (2013). Social-cultural dynamics and education for development in Zimbabwe: Navigating the discourse for exclusion and marginalisation. African Journal of Social Work 3(1):175-182. |

|

|

Briley DA (2009). Cultural Influence on Consumer Motivations: A Dynamic View. In Nakata C (ed.) Beyond Hofstede. New York: Palmgrave MacMillan. |

|

|

Bryman A (2008). Why do researchers integrate/ combine/mesh/ blend/mix/merge/fuse quantitative and qualitative research. Advances in Mixed Methods Research 21(8):87-100. |

|

|

Canabal JE (2002). Decision-making styles of young Indian consumers: An exploratory study. College Student Journal 36(1):12-19. |

|

|

Cant MS, Brink A, Brijbal S (2006). Consumer Behavior. 1st edition. Cape Town: Juta. |

|

|

Chen YJ, Chen PC, Lin KT (2012). Gender differences analysis cross-culturally in decision making-styles-- Taiwanese and Americans comparison. Journal of International Management Studies 7(1):175-182. |

|

|

Cronbach LJ (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16(3):297-334. |

|

|

Darden WR, Ashton D (1974). Psychographic profiles of patronage preference groups. Journal of Retailing 50:99-112. |

|

|

Ercis A, Unal S, Bilgili B (2006). Decision-making styles and personal values of young people. Available at: |

|

|

Fonseca JR (2011). Why does segmentation matter? Identifying market segments through a mixed methodology. European Retail Research 25(1)1-26. |

|

|

Glebkin VV (2015). The problem of cultural-historical typology from the four-level cognitive-development theory perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 46(8):1010-1022. |

|

|

Hofstede G (1980). Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. |

|

|

Hofstede G (2010). Comparing regional cultures within a country: Lessons from Brazil. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 41(3):336-352. |

|

|

Hofstede G (2011). Dimensionalising Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Psychology and Culture 2(1):2-26. |

|

|

Hofstede G (2013). Replicating and extending Cross-national values studies: Rewards and pitfalls- An example from Middle East studies. Academy of International Business Insights 13(2):5-7. |

|

|

Hofstede G, Bond M (2010). The Confucius Connection: From cultural roots to economic roots. Organisational Dynamics 16(4):4-21. |

|

|

Hofstede G, Minkov M (2010). Cultures and Organisations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill. |

|

|

Inkeles A, Levinson D (1969). National Character: The Study of Modal Personality and Socio-cultural Systems. In Lindey G, Aronson E (eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 418-506. |

|

|

Kamaruddin AR (2009). Malay culture and consumer decision-making styles: an investigation on religious and ethnic dimensions. Jurnal Kemanusiaan 14(5):37-50. |

|

|

Kluckhohn CK (1951a). The Study of Culture. In Lerner D, Lasswell HD (eds.), The Policy Sciences. Stanford: Stanford University Press pp. 86-101. |

|

|

Kluckhohn CK (1951b). Values and Value Orientations in the Theory of Action, in Toward a General Theory of Action. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. |

|

|

Kluckhohn FR, Strodbeck FL (1961). Variations in Value Orientations. Westport: Greenwood. |

|

|

Lastovicka JL (1982). On the validation of lifestyle traits: a review and illustration. Journal of Marketing Research 19(1):126-138. |

|

|

Leedy PD, Ormrod JE (2016). Practical Research: Planning and Design. 16th edition. Boston: Pearson Education. |

|

|

Lenartowicz T, Roth K (2001). Culture assessment revisited: the selection of key informants in IB cross-cultural studies. In 2001 Annual meeting of the Academy of International Business. pp. 23-26. |

|

|

Leng CY, Botelho D (2010). How does national culture impact on consumers' decision-making styles? A cross-cultural study in Brazil, the United States and Japan. BAR - Brazilian Administration Review 7(3):260-275. |

|

|

Mafini C, Dhurup M (2014). Consumer Decision Making Styles?: An Empirical Investigation From South Africa. International Business and Economics Research Journal 13(4):679-688. |

|

|

Manyena SB, Fordham M, Collins A (2008). Disaster Resilience and Children: Managing Food Security in Zimbabwe's Binga District. Children, Youth and Environments 18(1):303-331. |

|

|

Manyonganise M (2015). Oppressive and Liberative: A Zimbabwean Woman's Reflections on Ubuntu. Verbum et Ecclesia 36(2):1-7. |

|

|

Maunganidze F (2020). Dealing with gender-related challenges: A perspective of Zimbabwean women in the practice of law. Cogent Business and Management 7(1):1769806. |

|

|

Minkov M, Hofstede G (2011). The Evolution of Hofstede's Doctrine. Cross-Cultural Management: An International Journal 18(3):10-20. |

|

|

Mokhlis S (2009). An Investigation of Consumer Decision-Making Styles of Young-Adults in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Management 4(4):140-148. |

|

|

De Mooij M (2019). Consumer Behaviour and Culture. 3rd Edition. London: Sage Publications. |

|

|

Moschis GP (1976a). Shopping Orientation and Consumer Uses of Information. Journal of Retailing 6(8):61-70. |

|

|

Moschis GP (1976b). Social Comparison and Informal Group Influence. Journal of Marketing Research 1(13):237-244. |

|

|

Mothersbaugh DL, Hawkins DI (2016). Consumer Behavior Building Marketing Strategy (13th Edn) McGraw-Hill. |

|

|

Muyambo T (2018). Indigenous Knowledge Systems of the Ndau People of Manicaland Province in Zimbabwe: A Case Study of Bota reShupa. University of Kwazulu-Natal. |

|

|

Mwale C, Dodo O (2017). Sociocultural Beliefs and Women Leadership in Sanyati District. Journal of Social Change 9(16):107-118. |

|

|

Ndlovu M, Dube N (2012). Analysis of the relevance of traditional leaders and the evolution of traditional leadership in Zimbabwe: A case study of amaNdebele. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies - Multi- Inter- and Transdisciplinarity 7(1):50-72. |

|

|

Oppong NY (2013). Towards African Work Orientations?: Guide from Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions 5(20):203-213. |

|

|

Radder L, Li Y, Pietersen JJ (2006). Decision-Making Styles of Young Chinese, Motswana and Caucasian Consumer in South Africa: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Consumer Sciences 34(5):20-31. |

|

|

Rarick C (2013). An investigation of Ugandan cultural values and implications for managerial behaviour. Global Journal of Management and Business Research Administration and Management 13(9):1-9. |

|

|

Somekh B, Lewin C (2005). Research Methods in the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. |

|

|

Sproles GB (1979). Fashion, Consumer Behavior Toward Dress. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing. |

|

|

Sproles GB, Kendall EL (1986). A methodology for profiling consumers' decision-making styles'. Journal Of Consumer Affairs 20(2):267-279. |

|

|

Stephenson PR, Willet RP (1969). Analysis of Consumers' Retail Patronage Strategies. In McDonald PR (ed.) Marketing Involvement in Society and the Economy. Chicago: American Marketing Association pp. 316-322. |

|

|

Trochim WM, Donnelly JP (2001). Research methods knowledge base (Volume 2). Macmillan Publishing Company, New York: Atomic Dog Pub. |

|

|

United Nations (2020). World Economic Situation and Prospects 2020. Available at: |

|

|

Viriri N, Viriri M (2018). The Teaching of Unhu/Ubuntu through Shona Novels in Zimbabwean Secondary Schools: A case for Masvingo Urban District. Journal of African Studies and Development 10(8):101-114. |

|

|

Van Staden H, Van der Merwe D (2017). Addressing low-literacy in the South African clothing retail environment. Journal of Consumer Sciences. Available at: |

|

|

Wells WD (1974). LifeStyle and Psychographics. Chicago: American Marketing Association. |

|

|

Yee AS, Hooi KK (2011). Consumer Decision-Making Critical Factors: An Exploratory Study, in International Journal on Management International Conference. pp. 363-373. |

|

|

Zhang A, Zheng M, Jiang N, Zhang J (2013). Culture and consumers' decision-making styles: An experimental study in individual-level. In 2013 6th International Conference on Information Management, Innovation Management and Industrial Engineering pp. 444-449. |

|

|

Zimbabwe National Statistic Agency (2012). CENSUS 2012. Harare. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0