ABSTRACT

Exploitation of Non-Wood Forest Products (NWFP) is after agriculture and breeding the third source of income in Burkina Faso. Soumbala, made from alkaline fermentation of Parkia biglobosa seeds, is one of the most popular indigenous foods condiments very prized by the Burkinabes. This study aimed to assess the process practices and safety measures to ensures good quality along the production chain of soumbala. A literature survey followed by investigations was performed. Sphinx Millennium V4.5 software was used for data processing and analysis. The results showed that soumbala production is essentially a women activity with Mossi and Lobi the most active ethnic groups in soumbala manufacture. The organoleptic and nutritional qualities as well as safety and stability of soumbala depend on the production conditions. The production and sale conditions, the ignorance of rules of hygiene, the lack of training in quality management system or concept of good manufacturing practice (GMP) and the non-compliance practices of processors induced sanitary risks for consumers. Results of this study confirmed the needs to set up training program for GMP, environmental sanitation and personal hygiene both for processor-sellers to improve the safety of soumbala.

Key words: Technology of production, food safety, food quality, Soumbala, good manufacturing practice (GMP).

Leguminous oil seeds are cultivated in large quantities in many regions of West Africa. The seeds are fermented to produce highly priced traditional condiments, used as seasoning for soup and sauces as well as a source of plant proteins to supplement the dietary intake (Oguntoyinbo, 2012). Soumbala, along with other African fermented food condiments, is one of the popular food seasonings produced from alkaline fermentation of African locust bean (Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) G. Don) seeds in many West African countries (Savadogo et al., 2011; Ouoba, 2017; Akanda et al., 2018). The fermented seeds had various names according to the country where it is produced and is commonly called soumbala in Burkina Faso and Mali (Diawara et al.,1992). Soumbara, iru, netetu, afitin or sonru, Dawadawa and Kinda all also refer to the same product, in Côte d’Ivoire (Fatoumata et al., 2016), in Nigeria (Sanni et al., 2000), Senegal (Ndir et al., 1994), Benin (Azokpota et al., 2006), in Nigeria and Ghana (Akanda et al., 2018)and Serria Leone (Savadogo et al., 2011), respectively. Soumbala contained 30-47% proteins, 20-43% lipids and 13-17% carbohydrates, and constituted a great source of energy (464-546 Kcal/100 g), and is a rich source of essential amino and fatty acids (Parkouda et al., 2009). It is also rich in vitamins, especially vitamins of the B group (thiamine, riboflavin and niacin) (Ndir et al., 2000), and also in minerals such as calcium, iron and phosphorus. It has a characteristic strong flavor and odor attributed to the production of components such as ammonia, pyrazines, esters, acids and ketones during the fermentation and production technique (Ouoba, 2017). The diversified components, of soumbala contributed to add essential nutrients to monotonous carbohydrate-dominated diets of the rural populations. It is usually added generously as seasoning into the preparation of various dishes such as sauces, soups, “riz gras au soumbala”, “Poulet au soumbala”, “couscous”, etc. widely consumed in Burkina Faso (Somda et al., 2014). Soumbala served as a low-cost meat substitute for poorer sections of the community (Campbell-Platt, 1980)due to its content of protein and fat. Beside its flavoring attributes, soumbala played an important health maintaining role (Akanda et al., 2018)since, with its diverse components, it is believed to contribute to the regulation of arterial tension, to fight against cardiovascular illness and to contain beneficial bioactive compound-producing Bacillus strains that acted as probiotics in the human gastro-intestinal tract. It also played socio-economic and cultural role for the local Burkinabe population (Cheyns and Bricas, 2003; Millogo, 2008).

In Burkina Faso, the traditional processing and fermentation of African locust bean seeds into soumbala comprised the following mains steps: boiling of the seeds during 24-40 h, dehulling, second parboiling for 1-3 h, fermentation for 48-72 h (25-30°C), air drying and molding into balls of various sizes (Ouoba, 2017). This artisanal process relied on the know-how of small producers who make soumbala, in small manufacturing units, originally destined for house consumption. This technology is non-compliant in terms of both safety and quality of the final product (Somda et al., 2014; Ouoba, 2017). However, today, the production of soumbala is growing due to gradually increasing demand and the income generated by this activity for its main actors (Millogo, 2008). A semi-modern technology called ALTECH has been developed, by the Department of Food Technology of the National Research Centre (DTA/IRSAT/CNRST) (Millogo, 2008)and adopted in Ghana (Akanda et al., 2018)and Nigeria (Isu and Ofuya, 2000), for normalization and control of production of standard soumbala. Unfortunately, this semi-modern manufacturing unit did not produce enough soumbala and both technology and product are judged very-cost effective by producers and consumers, respectively (Millogo, 2008). As a consequence, the artisanal technology is still the main process for production of soumbala whose sale enhanced the economic empowerment of rural dwellers, and thus, contributed to poverty alleviation in Burkina Faso (Ouoba et al., 2003; Somda et al., 2014).

The uncontrolled process, based on the know-how of small producers, without application of a quality management system or understanding of the concept of good manufacturing practice (GMP) and plan hygiene (PH), together with the non-compliant sale practices of the product, lead to doubts in terms of hygienic and sanitary qualities of soumbala (Cheyns and Bricas, 2003; Ouoba, 2017). The characterization of microbial diversity of soumbala, have shown Bacillus subtilis as dominant bacteria (Oguntoyinbo et al., 2010; Ouoba, 2017). It is important to note that rudimentary equipment is used, the spontaneous fermentation process and the sale practices are potential sources for the development of spoilage and/or foodborne pathogenic bacteria such as Bacillus cereus, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, etc. responsible for the highest risk of foodborne diseases (Somda et al., 2014; Glover et al., 2018).

Therefore, it is important to evaluate the sanitary risks associated with processors’ practices in the production and sale of soumbala to inform those involved about corrective measures to be applied for improvement of safety of soumbala respecting the standard production norms and consumers’ needs (Cheyns and Bricas, 2003; Millogo, 2008; Ouoba, 2017). The methods used to carry out this study were used of a participatory risk analysis process associated with the practices of the actors and evaluating risks for the contamination of soumbala along the food chain. The exploitation of different practices of the producers-sellers can make it possible to meet the requirement for safety of soumbala produced in Burkina Faso, which led to the following questions: What are the quality and safety risky in the practices of the actors from the production to sale of soumbala? What are consumers’ opinions on the hygiene and sanitary qualities of the soumbala sold in Burkina Faso?

Consequently, this study aimed to update information on the technology practices’ of soumbala production, the consumers’ opinion on its quality and the risk factors associated with it along the food chain.

Literature research

A literature search was conducted to better understand what has been studied both on the theoretical and practical aspects of soumbala production and consumption.

Study areas and period

This study was conducted from March to June 2017 in the cities of four regions of Burkina Faso: Banfora (10°24'26.2"N; 4°33'44.7"W) in Cascades region, Bobo-Dioulasso (11°79’27” N; 4°12’11.90”W) in Hauts-Bassins region, Gaoua (10°19’50”N; 3°10’46”W) in Sud-Ouest region and Ouagadougou (12°22’44”N; -1°29’52”W) in Centre region. The studied areas are shown in Figure 1 (colored in Blue circles). These cities have been chosen based on their cosmopolitan character, the large production volume of soumbala in these regions and the income generated for local population, the interest given to the current consumption of soumbala in various diets linked to the high density of their population (particularly in Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso) and the socio-cultural diversity influencing the diet of people.

Investigation

A pre-investigation was used to test the questionnaires with soumbala actors (producer-sellers and consumers) speaking different local dialects. This made it possible to adapt the questionnaire to the sociological realities. The questionnaires were given individually to the producer-sellers and consumers. A total of 160 persons, chosen randomly were investigated, this included 80 producer-sellers and 80 consumers (20 per city and category). The information requested in the questionnaires serving as a guide to score the sociodemographic status of the respondents, to describe the technological aspects of soumbala production, consumer’s assessment of quality, and health risks linked to their different practices.

Statistical analysis

Sphinx Millennium V4.5 software (Le sphinx Développement 7450 Chavanod, France) was used for survey data processing and a Chi2 test was used for analysis of variance at a significance threshold of p<0.05.

Overview of the socio-economic importance of soumbala, a non-wood product derived from exploitation of P. Biglobosa seeds in Burkina Faso

A Non Wood Forest Product (NWFP) can be defined as welfare and services, others than work woods, resulting from renewable forest resources such as forest, wooded lands and outside forest trees (Lamien and Bamba, 2008). It exploitation allowed the populations to support their essential needs (Foods, health, construction, handicraft and socio-cultural) and served as economical source for local communities. NWFPs constituted the third place after agriculture and breeding as sources of income and they represented 23% of the global income for the population in Burkina Faso (Sama and Koukou-Tchamba, 2010). NWFPs employed 10% of the labor force, 80% of households are involved and contributed around 10% of the Gross Domestic Product (PIB) and represented around 10% of the country total experts. It contributed about 16 to 27% in the income of women in Sud-Ouest region (Ministère de l’Environnement et du Cadre de Vie (MECV), 2010).

Three regions harbor the majority of Burkina Faso’s NWFPs, particularly the production of P. biglobosa seeds. These regions are the Cascades, Haut-basins, and Sud-Ouest, which are recognized as centers of the production of African locust bean seeds (Cheyns and Bricas, 2003; Sama and Koukou-Tchamba, 2010). According to the annual statistics report (Agence de Promotion des Produits Forestiers Non Ligneux (APFNL), 2013)elaborated in 2012, around 214 tons of P. biglobosa seeds and 48 tons of soumbala have been commercialized in Burkina Faso, generating incomes of 6.14 and 7.20 billon FCFA (Currency coins of the Central African CFA franc), respectively. The income generated from soumbala constitutes a major component of the gross income of those involved (Millogo, 2008).

The increasing demand of consumers for natural, local and safe foods seasonings have promoted further development of artisanal production of soumbala. To be able to meet this need, the DTA/IRSAT/CNRST has developed a semi-modern technology ALTECH for industrialization of soumbala production process (Millogo, 2008). It is presumed that valorization and promotion of soumbala would be contributed to food security and sustainable development (Millogo, 2008)with poverty alleviation to the local population in Burkina Faso (Millogo, 2008; Ouoba, 2017; Somda et al., 2014).

Socio-cultural characteristics of producer-sellers and consumers of soumbala

Table 1 presents the socio-cultural characteristics of the participated population which constituted 20% men and 80% women. The results from the investigations showed that the production and sale of soumbala are done by women (100%). The producer-sellers were regrouped in four age groups: the first group constituted of 3.75% of the respondents younger than 25 years, the second group contained 2.50% and are those from 26 to 30 years, the third group comprised 8.75% of the respondents and are 31 to 35 years while the last group included 85.5 % of the respondents and are held than 35 years with high significant difference (Chi2=187.30, P=0.0001).

The educational background had the following distribution: 68.80% of producers-sellers were illiterates, 2.50% have received local language training, 22.5% went to primary school, and 6.30% had secondary level education with high significant difference (Chi2=88.90, P<0.0001). Consumers were composed of 46.30% men and 53.80% women, and for the four age groups: the first group held 25.50% of the respondents, the second groups represented 17.5%, and the third group formed 12.65%, while the last group included 45.00% of the respondents. The difference in distribution of age of respondent’s population is very significant (Chi2= 62.75, P<0.0001). Total of 25.00% of consumers were illiterates, 8.80% received local language training, 1.30% have Franco-Arab instruction, 32.5% went to primary school, 16.30% have secondary level education and 16.30% have university education with high significant difference (Chi2= 29.80, P<0.0001).

The surveyed population included 14 socio-ethnic groups. The main participants were Mossi composed of 32.5% producer-saleswomen and 23.8% of consumers, and Lobi constituted 17.5% producer-saleswomen and 26.3% of consumers with a high significance (Chi2= 95.14, P<0.0001). In terms of religion, the surveyed population was formed of 43.70% Muslim, 41.25% Christian and 15.0% Animist.

Socio-economic characteristics of the actors in soumbala production-sale

The production of soumbala is dominated by women (Table 2). These actors are found in the peri-urban and urban zones and produced soumbala individually (100%) in their homes. The producers attested to know the full flow diagram of the soumbala processing and 77.60% had more than 10 years’ experience. They buy the African locust bean seeds from collectors-sellers (100%) but sometime some are self-suppliers of seeds (5%). They produced soumbala all the seasons for socio-cultural (42.5%) and/or economic (97.5%) reasons with high significance (Chi2=17.29, P=0.0002).

The processors are wholesalers (73.80%) and/or retailers (98.80%) of soumbala in local market places (100%) and at their home place (60%). They reported being able to sale the totality (80%) or the half (32%) of their product per week at the unitary prize of 25 F CFA/soumbala ball. The majority of producer-sellers (91.5%) reported profitability of their activity, and the income generated used to maintain their economic activity and various household costs (100%).

Practices in the production of soumbala

Production technique of soumbala and its distribution chain

In Burkina, soumbala is mainly produced by traditional technology. The main steps of traditional process for soumbala production are summarized in Figure 2, and in Table 2 it is shown that this technique is still the main process used by processors (100%) in the survey study areas. The soumbala is made manually in a familial place (Kitchen) involving a restricted workforce of 1-3 workers (91.3%) or 4-6 persons (7.5%) able to transform 10 (3.8%), 20 (25%) or 30 kg (72.5%) of seeds per month with high significant difference (Chi2 =58.74, P<0.0001). Aluminum pot (100%) or canaries (17.5%) are used for woods-boiling of seeds during almost 24 h with addition of potassium (alkaline ash) (17.5%) to allow the softening of seeds. The softened seeds are then pounded in mortar (100%) with addition of ash (58.8%) or sand (55%) to allow cotyledons dehulling. Then, the dehulled cotyledons are washed using faucet/tap water (60%), pipe borne water (37.5%), well water (21.3%) or stream/river course water (8.8%). After washing, the cotyledons are drained, sorted and parboiled twice for 1 to 3 h. The parboiled cotyledons are drained-cooled for 30 min in a pannier. For fermentation, the resulting cotyledons are spread onto plastic bag/tank (70.1%), in panniers (46.3%), canary (25%) or calabash (2.5%). Some producers spray millet floor (12.5%), salt powder (10.00%) onto

cotyledons, and cover it with fresh leaves (8.8%). The product is then submitted to spontaneous fermentation for 2 to 3 days. The fermented condiment resultant is slightly sun-dried almost 8 h and directly rolled into balls (85%) or often ground and mounded in balls (30%). Soumbala balls are more sun-dried, unpacked and keep in pannier (63.7%), bowl (22.5%), and plastic bag (12.5%) or in canary (1.3%) for sale.

From production to sale, the soumbala followed different routes as shown in Figure 3: the direct route (1) from the producer-sellers to consumers and the indirect route (2) from producer-wholesalers to purchaser-resellers or supermarkets who supply the consumers. A third circuit (3) existed between parents or related close persons, who sometime supply soumbala as a gift to consumers. The importance of the different routes depended on the quantity of soumbala produced and the actors involved.

Consumer’s assessment on the condition of soumbala production and sale

Table 3 shows the consumer’s assessment of the condition of soumbala production and sale. Respondents consumed soumbala daily (88.80%) or every two days (11.30%) in various dishes with high significant difference (Chi2 = 111.47, p<0.0001) in consumption frequencies. The dominant ethnic group consumers were Lobi (26.30%) and Mossi (23.80%) with high significant difference (Chi2 = 208.75, p<0.0001). Women were the main group of consumers with high significant difference (Ch2 = 49.56, p<0.003). The whole cotyledons balls were the most consumed form of soumbala (92.50%) with highly significant difference (Chi2 = 103.23, p<0.0001). The reasons given were multiple and varied from one to another consumer (Table 3). The major part of consumers (65.00%) know the origin of soumbala, and the main supply sources were producers’ sites (60.00%) and/or the markets/streets (67.50%) with high significant difference (Chi2 =93.50, p<0.0001). Consumers (100%) had good appreciation of soumbala and its taste varied from one consumer to another as shown in Table 3 with high significant difference (Chi2 = 95.06, p<0.0001). The criterion of choice both of seller and soumbala varied from one consumer to another (Table 3) and the main reasons given were the search of good food enhancer and their health enhancement (95.00%). The price of sale of condiment was judged acceptable by half consumers (50.00%) with high significant difference (Chi2 = 62.189, p<0.0001). However, some consumers (32.00%) doubted the safety and quality of soumbala sold, even though it met the expectations of majority (98.00%).

All consumers found that the production of soumbala is artisanal, and their expectation for improvement of quality of soumbala varied from one to another (Table 3). Only 8.80% of consumers know the existence of semi-modern technology, whereas 72.50% of all consumers think that this technology could help to improve production of soumbala.

Sanitary risk along the food chain

Sanitary risk of soumbala processing-sale

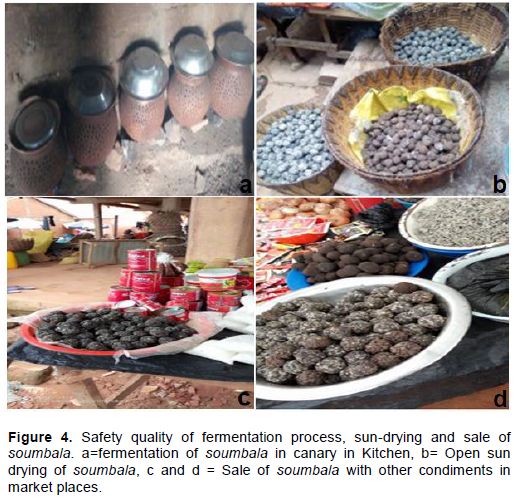

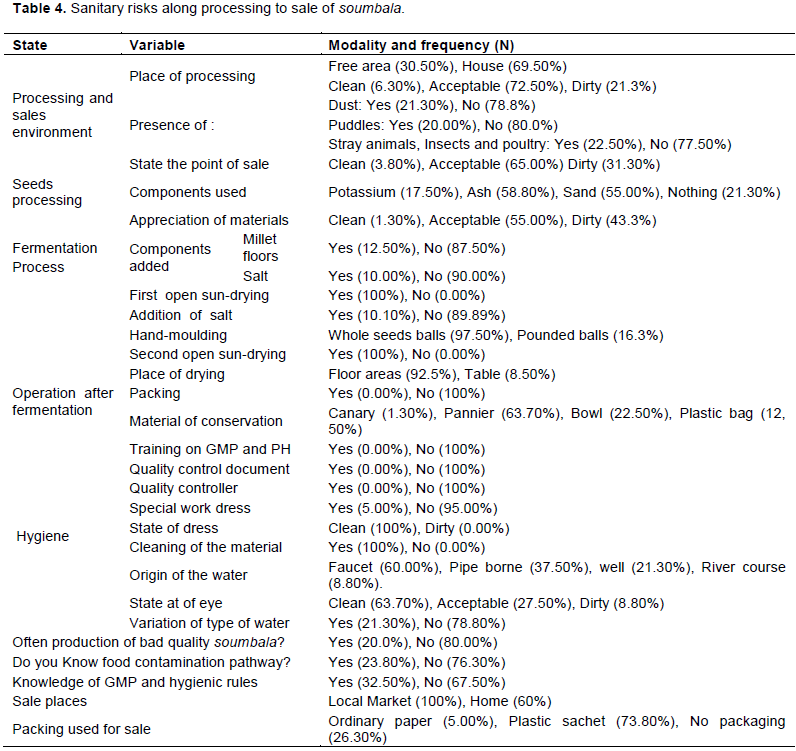

The artisanal processing of soumbala and its sale practices in the local markets (Figure 4) are associated with some sanitary risks that often make the product questionable for health and safety for the consumers. The place of processing and the sale environment was considered as some of the main risks of soumbala contamination in addition to the practices of processor-sellers (Table 4). Soumbala processors produced their condiments at home and interference with domestic activities and animals were observed.

The processing of African locust bean seeds involved a restricted workforce of 1 to 3 persons (91.3%) without any training on good manufacturing practices and hygiene rules. The seeds processing (boiling, dehulling and washing) are mainly done in an open area and fermentation took place in the kitchen of the houses. Certain processors used alkaline ash (potassium) (17.50%) for seeds softening during the first boiling, ash (58.80%) and/or sand (55.00%) to allow cotyledons dehulling during the seeds peeling in mortar, with high significant difference (Chi2 = 65.46, p=0.0001). The water used for processing is from various sources: faucet/tap (60%), pipe borne (37.50%), well (21.30%) and stream/river course (8.80%), and stored in canary (local pot), metal drums or plastics bowls with high significant difference (Chi2 = 36.90, p≤0.0001). It was clean (67.30%), however, some processors (21.30%) have reported to vary the type of water used. Aluminum pots (100%) or canaries (17.50%) were the main cooking equipment, while fermentation was conducted in plastic bag/jute (72.50%), in panniers (46.30%), in canary (25.00%) or in calabashes (2.50%) with high significant difference (Chi2 = 79.18, p<0.0001). These fermentation equipment were found dirty (43.8%) with high significant difference (Chi2 = 38.50, p≤0.0001).

For the spontaneous fermentation process (Figure 4a), some producers spray millet floor (12.5%), table salt (10.10%) onto cotyledons, and cover it with fresh leaves (12.50%) with high significant difference (Chi2 = 96.27, p<0.0001). The obtained soumbala is either hand-rolled directly into balls (97.50%) or ground and hand-moulded in balls (13.80%) and then sun-dried on an open floor place (92.50%) or on a table (8.50%). The soumbala balls were sun dried more (Figure 4b) during 2 days (70.00%) or 3 days (30.00%) with high significant difference (Chi2 = 12.80, p=0.0001). Then, it was unpackaged (100%) and conserved either in pannier (63.70%), bowl (22.50%), plastic bag (12.50%) or canary (1.30%) with high significant difference (Chi2 = 65.46, p≤0.0001). Some processors (20.00%) attested to often produced bad quality soumbala with high significant difference (Chi2 = 28.80, p≤0.0001).

The producers sold their unpacked soumbala at home (60%) or in the open area market places (100%) (Figure 4c and d) with significant difference (Chi2 = 8.00, p=0.01). They used plastic sachets (73.8%), ordinary papers (5.00%) or nothing (26.30%) to sale soumbala with high significant difference (Chi2 = 56.64, p≤0.0001). The presence of dust (21.30%), puddles (20.00%), stray animals, insects and poultry (22.50%) was observed from some producers’ sites and places of sale.

For the sanitation level, 21.30 and 31.30% of processors had dirty places of processing and sale, respectively. Places of sale were found dirtier than the places of processing based on hygienic conditions. In terms of hygiene, no producer-sellers had a quality monitoring manual and quality control process in place. Only, 23.80% attested to know food contamination pathway and 32.50% have knowledge of GMP and PH.

5.00% of the producer-sellers used special clean work dress that was found clean (100%). All processors (100%) attested to regularly washing their production equipment.

Sanitary risk analysis from consumers

The sanitary risks linked to consumers’ practices are summarized in Figures 5 to 7. As shown in Figure 5, 76.30% of consumers attested that producers applied GMP and PH, 35.00% did not know the origin of soumbala, and 7.50% conserved the bought condiment for almost 1 month before use. More than half (56.30%) reported to encounter some impurities in the product bought with a significant difference (Chi2 = 12.80, p<0.0003). Some cases of sickness were reported by 15.00% of consumers after consumption of soumbala dishes with a significant difference (Chi2=10.25, p<0.03).

However, only 2.5% of them went to health centre. In a case of visible alteration (Figure 6A), soumbala was not consumed (87%) or arranged for consumption (13%). Clinical signs are shown in Figure 6B. Only 2.5% of concerned people went to health centre.

The perception of state of sales environment and opinion on soumbala quality differed from one locality to another and from one consumer to another (Figure 7) with a significant difference (Chi2 = 30.92, p<0.0001). To buy soumbala, consumers used indirect qualification (86.3%) based on its taste, odor, color, appearance, and/or direct qualification (70.0%) based on confident relationship with producer-seller. The hygienic quality is one of the major factors that could limit soumbala consumption as suggested by the majority of consumers (87.5%) in Figure 7 with a significant difference (Chi2 = 62.29, p< 0.03).

Soumbala is an alkaline condiment of West Africa, very prized by the local populations. It is used in cooking of various dishes, preferentially in the preparation of sauces of rice, soups, couscous, Poulet au soumbala, riz gras au soumbala, and other dishes basis of cereals in Burkina Faso (Somda et al., 2014). It is a rich source of essential nutrient and vitamins that contributed to enhance food taste and flavor and to fight against malnutrition (Ouoba, 2017). Soumbala contributed to food diversification and security and nutritional balance and to improve health of consumers. Its production served as economic source for rural household women (Millogo, 2008; APFNL, 2013).

The study of sociocultural characteristics of the respondents showed that they are constituted of men and women of different age’s groups. The majority have limited level of education. The main actors in the soumbala sector are women, with Mossi (28.12%) and Lobi (21.87%) as the dominant ethnic groups (Table 1). Mossi is the dominant ethnic group in Burkina Faso and was found before (Cheyns and Bricas, 2003)to be one of the main ethnical groups responsible for soumbala production and current consumption (Somda et al., 2014).

The traditional process used by local producers for soumbala production was originally based on know-how of elderly women who transfer their empirical knowledge from generation to generation within the family. Thereby, the young girls learned with their mothers or close related persons since the processing of soumbala is perceived as an important culinary art and identity typical to each ethnic group and transfers to the more confident person of the family. However, today, with the growing demand of soumbala often linked to poverty and the need of for income, non-experienced young women in the urban areas with less training and indigenous culinary art knowledge produce soumbala that is often rejected by some consumers because of their low quality and unsafe (Cheyns and Bricas, 2003).

The results of investigations showed that the hygienic status quality and safety of soumbala are very doubtful based on various practices of producers-sellers. The majority of processors are illiterate (68.80%) and exert their activity in poor hygienic conditions. These producers have limited knowledge of GMP and Plan Hygiene (PH) and produced soumbala of doubtful quality and safety. They collect P. biglobosa seeds on tree or market and process the seeds in their homes in non-adequate hygienic conditions. The physical conditions and infrastructure in the sites of soumbala production are generally poor. Their artisanal processing of soumbala, using rudimentary equipment and spontaneous fermentation, led to a final product with varying quality from one ethnic group to another and one region to another (Millogo, 2008). Practices such as use of ash and/or sand for seed dehulling, spreading of millet floor onto cotyledons and covering with fresh leaves (12.5%) for spontaneous fermentation in simple equipment such as plastic bags or panniers are some of the main points of lack of GMP and hygiene affecting the quality of condiment. Additionally, hand-moulding, use of an open area for sun drying and the lack of wrapper even though some sellers affirm to use plastic sachets for sale as well as unsuitable sale conditions, increase the non-compliant hygienic status of soumbala. Of course, the equipment and preparations of fermented condiments still lack safety and quality controls while packaging and presentations are traditional. The various practices in many of the steps are critical points with high risk and source for microbial contamination during production and sale of soumbala. Indeed, the condiment is stored and sale in inappropriate conditions and exposed to the effects of moisture, dust, and temperature as well as to microbial and insect attack. There is no subsequent step to eliminate possible pathogenic microorganisms that could be led to health risks for the consumers. Overall, the final product proposed to the consumers is sometimes of poor hygienic quality (Somda et al., 2014).

Following the above information, due to its increasing demand with the context of urbanization, DTA/IRSAT/CNRST has designed a semi-modern technology called ALTECH to standardize the production of soumbala (Cheyns and Bricas, 2003; Millogo, 2008). This technology is using mixed-starter cultures of Bacillus subtilis strains to obtain the original organoleptic characteristics of artisanal soumbala consumed by the consumers of different ethnic background as cultural identity specific to each dialect and locality. Unfortunately, this technology no longer produced soumbala due to the seasonal availability of raw material and equipment cost and unavailability to the rural low incomes producers (Millogo, 2008). Hence, the traditional process remained the main technology. Today, the stakeholders who are mostly illiterates need training session in GMP and PH to improve the technology and quality of their products to satisfy the needs of consumers especially the urban consumers.

The marketing distribution circuit of soumbala is entirely driven by women composed of producers-sellers. This activity is well known as women’s job since processed vegetable foods are commonly sold in markets and streets by producers-saleswomen. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies on the traditionally processed soumbala sold in Burkina Faso (Cheyns and Bricas, 2003; Millogo, 2008; Ouoba, 2017). Indeed, soumbala marketing played an important socio-economic role since the incomes generated maintain their activities and to manage household spending. Thus, women used a part of their income to buy food, pay family bills, pay schools fees etc. (Millogo, 2008)and so the generated incomes represented an important part in the economy of rural women and poverty alleviation in Burkina Faso (MECV, 2010; Somda et al., 2014).

In term of consumption, 88.8% of the respondents consumed soumbala on a daily basis for and every second day for the others (11.3%) mainly during family meals. Women are the major group of consumers and they are also the main actors in processing and sale of soumbala. This food seasoning is used to enhance the flavor and taste of various dishes as others similar local fermented food condiments such as bikalga (Parkouda et al., 2008)and Maari (Kaboré et al., 2012). There are many reasons given by consumers for soumbala consumption such as food taste enhancer, increase nutritional value, therapeutic virtue, cultural identity and improvement of man virility. Similar reports have been given (Cheyns and Bricas, 2003; Millogo, 2008). Indeed, soumbala is found to be rich in essential nutrients and some vitamins ( Ouoba, 2017)and served as a low-cost meat for poor people. Its consumption is believed to help to fight against malnutrition of children, to regulate arterial tension preventing cardiovascular illness, to prevent and/or to fight against diabetes.

However, the practices in use make the consumption of soumbala a major sanitary risk. The criteria used by consumers to buy soumbala based on indirect qualifications and/or direct qualifications are non-standard. Indeed, despite the use of these criteria to purchase good quality of soumbala, incertitude appeared in the quality of this traditional condiment, since a non-negligible number of consumers reported to often find impurities such as sand, plastic or vegetable debris, dust, insect in soumbala. Unfortunately, some of them (15.00%) still used altered soumbala. Consequently, cases of illness such as digestive trouble, nausea, stomach aches, and diarrhea have been reported by consumers after consumption of soumbala dishes (Figure 6). However, only a few numbers visited a health centre in case of illness.

Therefore, the nutritional and socio-economic valorization and the promotion of soumbala based on norms of hygiene and quality required structural reorganization of economic actors in groups/associations, cooperatives, unions and finally federation (APFNL, 2013). These economic interest group (EIG) can benefit from training on the GMP and hygienic rules for the production of safe and higher quality soumbala. Thus, they can be obtained for their product a quality norm from Directorate for Standardization and Quality Promotion (FASONORM), a certificate on the sanitary quality from Food Technology Direction (DTA) of IRSAT or National Laboratory of Public Health (NLPH). Moreover, the national federation could benefit from appropriation of license and protected label trade from the African Organization of Intellectual Property (AOIP) for the promotion of soumbala at international level.

This study was designed to evaluate safety and quality linked to the different practices applied during the production and sale of local soumbala in Burkina Faso. Results obtained in this study revealed that the sanitary risk associated to these practices for the consumers challenge, all actors in the production/distribution/ consumption of soumbala to enable a healthy diet, as well as educate and raise awareness of good hygiene practices and sanitation to protect the health of consumers. There is an essential need to set up training programs on sanitary condition for traditional producers-sellers to allow them to incorporate good manufacturing practices and plant hygiene to ensure production of more safe and higher quality soumbala with desired organoleptic characteristics and nutritional quality meeting the ever-growing demand and needs of urban and other consumers. The nutritional quality and therapeutic values of soumbala and the source of income generated for the producers, indicated the necessity to adopt and spread the mastered technology ALTECH of DTA/IRSAT. This novel technology should be available at low-cost to rural producers for the best valorization and promotion of marketable soumbala production and poverty alleviation. Reorganization of actors is required in provincial and regional cooperatives. The authorities should create mechanisms for quality and hygienic control to adhere these norms, and it should be obligatory. Finally, if the government intensifies actions in favor of soumbala actors; some of the goals can be accomplished in the near future: The adoption of the modern ALTECH technology for all association producers, adoption of quality norms for soumbala producers by the provincial and regional unions and improve trustworthiness of the consumers.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

The authors wish to express their profound gratitude to the German DAAD service for their financial support to one of the authors (Yérobessor DABIRE) through it In-Country/In-Region Scholarship Programme 2017 (57377184), University of Nigeria Nsukka (UNN), Enugu State, Nigeria. They also express their gratitude to Dr. Abel TANKOANO for his help in the questionnaire designed, Dommongnere DABIRE, Sipouté DAH, and Lehimwin Sylvère DABIRE for their help during the investigation.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Agence de promotion des Produits Forestiers Non Ligneux (APFNL) (2013). Annuaire de statistiques quantitatives sur l'exploitation des produits forestiers non ligneux. Rapport National 2012 FAO: Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso 36p.

|

|

|

|

Akanda F, Parkouda C, Suurbaar J, Donkor AM, Owusu-Kwarteng J (2018). Effects of mehanical dehulling on microbiological characteristics and chemical changes during processing of Parkia biglobosa seeds into dawadawa, a West African alkaline fermented condiment. Journal of the Ghana Science Association 17(2):13-19. Azokpota P, Hounhouigan DJ, Nago MC (2006). Esterase and protease activities of Bacillus spp. from afitin, iru and sonru: three African locust bean (Parkia biglobosa) condiments from Benin. African Journal of Biotechnology 5(3):265-272.

|

|

|

|

|

Campbell-Platt G (1980). African locust bean Parkia species, and its West African fermented food product, dawadawa. Ecology of Food Nutrition 9(2):123-132.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cheyns E, Bricas N (2003). La construction de la qualité des produits alimentaires: Le cas de soumbala, des céréales et des viandes sur le marché de Ouagadougou au Burkina Faso, Alimentation et savoir faire en Agroalimentaire en Afrique de l'Ouest. CIRAD: Montpellier, France 82p. (Série ALISA) ISBN 2-87614-540-5.

|

|

|

|

|

Diawara B, Sawadogo-Lingani H, Kaboré IZ (1992). Contribution à l'étude des procédés traditionnels de fabrications de soumbala au Burkina Faso. Aspects biochimiques, microbiologiques et technologiques. Science and Technology 20:5-14. ISSN: 1011-6028.

|

|

|

|

|

Fatoumata C, Soronikpoho S, Souleymane T, Kouakou B, Marcellin DK (2016). Caractéristiques biochimiques et microbiologiques de moutardes africaines produites à base de graines fermentées de Parkia biglobosa et de Glycine max, vendues en Côte d'Ivoire. International Journal Biological and Chemical Science 10(2):506-518.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Glover RLK, Madilo FK, Terlabie JL, Ametefe EN, Jespersen L (2018). Some technological properties of selected strains of Bacillus spp. associated with kantong production in Ghana. International Food Research Journal 25(2):602-611.

|

|

|

|

|

Isu NR, Ofuya CO (2000). Improvement of the traditional processing and fermentation of African oil bean (Pentaclethra macrophylla Bentham) into a food snack-Ugba. International Journal of Food Microbiology 59(3):235-239.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kaboré D, Thorsen L, Nielsen SD, Berner ST, Sawadogo-Lingani H, Diawara B, Dicko HM, Jakobsen M (2012). Bacteriocin formation by dominant aerobic spore formers isolated from traditional maari. International Journal of Food Microbiology 154:10-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lamien N, Bamba A (2008). Valorisation des Produits Forestiers Non Ligneux au Burkina Faso : Etat des lieux et perspectives. Programme d'Amélioration des Revenus et de Sécurité alimentaire (ARSA) : Composante «â€¯Exploitation rentable des Produits Forestiers Non Ligneux (PFNL). Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso 155p.

|

|

|

|

|

Ministère de l'Environnement et du Cadre de Vie (MECV) (2010). Programme d'investissement forestier (PIF-Burkina Faso). Aide-Mémoire Mission Préparation du PIF Burkina Faso. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, Octobre 2010 40p. Avaiable at:

View. (Assessed July 26, 2019).

|

|

|

|

|

Millogo F (2008). Analyse socio-économique de la production du soumbala dans la région des Hauts-Bassins avec comparaison des types de production traditionnelle et semi moderne (altech). Mémoire de fin de cycle en vue de l'obtention du diplôme d'ingénieur du développement rural. Mémoire de fin de Cycle, Université Polytechnique de Bobo-Dioulasso 56p.

|

|

|

|

|

Ndir B, Hbid C, Cornelius C, Roblain D, Jacques P, Vanhentenryck F, Diop M, Thonart P (1994). Propriétés antifongiques de la microflore sporulée du nététu. Cahiers Agriculture 3:23-30.

|

|

|

|

|

Ndir B, Lognay G, Wathelet B, Cornelius C, Marlier M, Thonart P (2000). Composition chimique du nététu, condiment alimentaire produit par fermentation des graines du caroubier africain Parkia biglobosa Jacq, Benth. Biotechnol, Agronomy, Society and Environment 4:101-105.

|

|

|

|

|

Oguntoyinbo FA (2012). Development of Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) and enhancement of microbial safety quality during production of fermented legume based condiments in Nigeria. Nigerian Food Journal 30(1):59-66.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Oguntoyinbo FA, Huch M, Cho GS, Schillinger U, Holzapfel WH, Sanni AI, Franz CMAP (2010). Diversity of Bacillus species isolated from okpehe, a traditional fermented soup condiment from Nigeria. Journal of Food Protection 73(5):870-878.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ouoba LII, Rechinger K B, Barkholt V, Diawara B, Traore A S, and Jakobsen M, (2003). Degradation of proteins during the fermentation of African locust bean (Parkia biglobosa) by strains of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus pumilus for production of soumbala. Journal of Applied Microbiology 95(4):868-873.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ouoba LII (2017).Traditional alkaline fermented foods : Selection of functional Bacillus starter cultures for soumbala production. In: Speranza B, Bevilacqua A, Corbo MR, Sinigaglia M (1st Edtion),Starter cultures in food production. Ltd: Hoboken, New Jersey (NJ), United States: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 370-383.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Parkouda C, Diawara B, Ouoba LII. (2008). Technology and physico-chemical characteristics of bikalga, alkaline fermented seeds of Hibiscus sabdariffa. African Journal of Biotechnology 7:916-922.

|

|

|

|

|

Parkouda C, Nielsen D S, Azokpota P, Ouoba LII, Amoa-Awua WK, Thorsen L (2009). The microbiology of alkaline-fermentation of indigenous seeds used as food condiments in Africa and Asia. Critical Review in Microbiology 35(2):139-156.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sama G, Koukou-Tchamba A, Ouedraogo GG (2010). Etude sur l'économie, le marché, la commercialisation et la fiscalité des produits forestiers non ligneux, exemple du néré (Parkia biglobosa), de la liane goine (Saba senegalensis), du prunier d'Afrique (Sclerocarya birrea). Ministère de l'Environnement et du Cadre de Vie. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso 86p.

|

|

|

|

|

Sanni S, Ayernor I, Sakyi-Dawson GS, Sefa-Dedeh E (2000). The production of owoh - a Nigerian fermented seasoning agent from cotton seed Gossypium Hirsutum L. Food Microbiology 8:223-229.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Savadogo A, Jules IA, Gnankiné O, Traoré AS (2011). Numeration and identification of thermotolerant endospore-forming Bacillus from two fermented condiments bikalga and soumbala. Advances in Environmental Biology 5(9):2960-2966.

|

|

|

|

|

Somda MK, Savadogo A, Tapsoba F, Ouédraogo N, Zongo C, Traoré AS (2014). Impact of traditional process on hygienic quality of soumbala a fermented cooked condiment in Burkina Faso. Journal of Food Security 2(2):59-64.

|

|