ABSTRACT

The current fast growth of the city of Dodoma in central Tanzania threatens cultural heritage materials scattered on the landscape. However, natural processes such as weathering and erosion also add to this threat. Earlier, we reported on the existence of two cultural traditions on this landscape, the Middle Stone Age artefacts and the much younger Wambambali tradition based on pottery, grinding stones and remains of collapsed buildings. This paper presents qualitative data about the latter tradition from the perception of elders. Although our main focus was on the Wambambali tradition, elders broadened our scope and so we discuss the Wambambali on the wider perspective that includes succeeding communities, the Wagogo. Interview and focus group discussion techniques were used to collect data. The current whereabout of the Wambambali people is not known but there are two suggestions: The majority went south while a small group may have gone to the north. On the other hand, the Wagogo communities are formed by founders from different ethnic groups and regions and elders involved in our research predominantly trace their origins to the Hehe and Bena communities in today’s Iringa/Njombe regions. The collective name for these incoming groups came to be known as Wagogo.

Key words: Origin, disappearance, Wambambali tradition, Wagogo, cultural heritage.

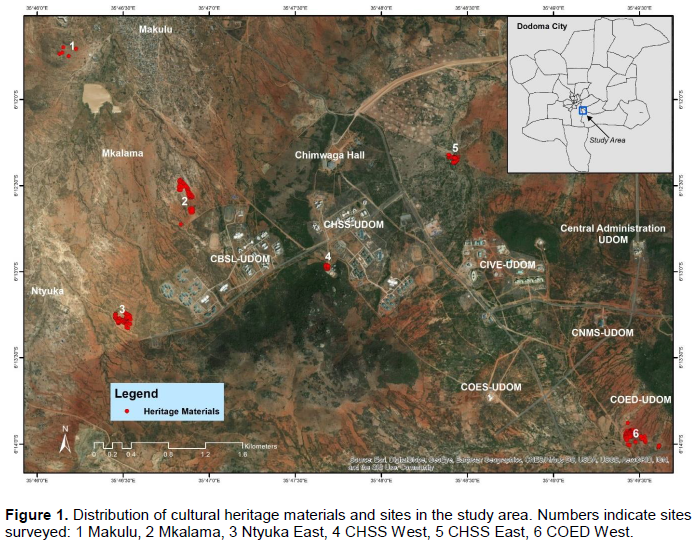

Due to the expansion of the capital city of Tanzania, Dodoma, cultural heritage materials around the new city are at a higher risk of destruction. The destruction is mainly from infrastructural development projects carried out by institutions such as universities, other projects targeting at improving the city to accommodate government and business activities, and farming. Natural processes such as erosion and weathering also threaten the heritage materials although this damage may not be to the extent affected by man-made activities. A salvage study was conducted between 14 and 28 August, 2018 to map and detail some of these materials and sites (Figure 1) that we could access given the resources we had at the time. In that rescue work, land walkover or pedestrian surveys, interview and focus group discussions with elders, and some minor excavations were conducted.

In our first publication regarding the results of this research (Ryano et al., 2020), we reported the existence of two traditions, the old tradition represented by lithic artefacts designated to the Levalloisian Industry of the Middle Stone Age (MSA); and the much younger tradition created by farmers and possibly pastoralist communities generally known through oral tradition as Wambambali (Mnyampala, 1995). The focus here, however, is the latter tradition particularly from the interview and focus group discussions as narrated by the elders. In the first paper (Ryano et al., 2020), we reported this only briefly and here we detail the results from interview and group discussions. Our land walkover surveys, both informal and formal, showed that the material remains of Wambambali tradition are distributed over a wide area both within the present urban settings of Dodoma and in the nearby rural areas including Bahi District, particularly at Mundemu Village. The material artefacts are largely in the form of collapsed buildings represented by chunks of burnt-daub, grindstones, and pottery fragments with various characteristic features (Ryano et al., 2020).

The team is still in preparation to continue research with the intention of dating materials to establish how old the Wambambali tradition is. However, working on Mnyampala (1995)’s estimation that Wagogo people arrived to Dodoma by AD 1300, in our research report (Ryano et al., 2020) we tentatively suggested that Wambambali tradition may date to the end of the first millennium AD and most possibly before that time. As will be seen below, the Wagogo oral tradition about Wambambali is largely associated with the material evidence scattered on space, as none of the Wagogo founders saw the Wambambali people; instead they only found artefacts and features. At this stage it is difficult to estimate the time lag between the Wagogo and Wambambali communities because several centuries may have passed after Wambambali but there is also a possibility of an overlap of the two traditions (Ehret, 1984; Maddox, 1995). However, future scholarship will answer this question firmly based on datable materials from archaeological excavations.

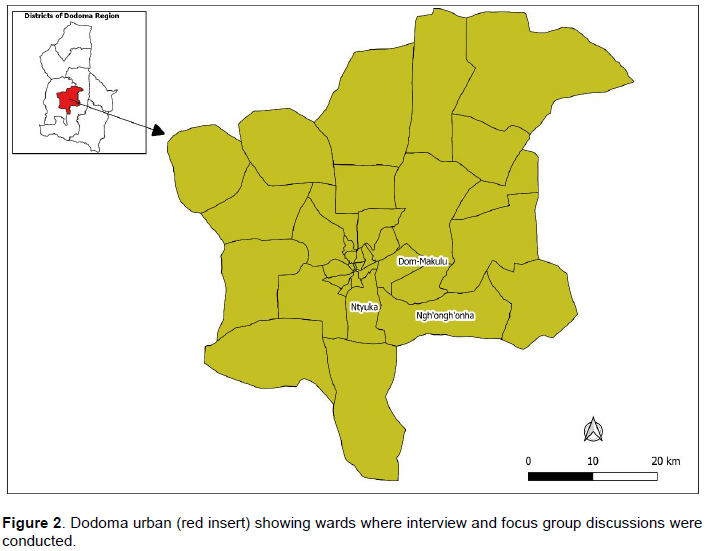

Materials in our study included qualitative information from interview and focus group discussions. These conversations from interview and focus group discussions were conducted at three suburbs or wards: Makulu (also called Dodoma-Makulu), Ng’ong’onha, and Ntyuka (Figure 2). These three suburbs were selected based on the proximity with Wambambali artefacts and features and they are therefore part of the initial proposed area of investigation, the University of Dodoma and its peripheries. Interview and focus group discussions involved elders that were identified through our research assistants and one of the authors (ET) identified the elder at Ntyuka suburb, as he knew the elder from a previous heritage related research. The elders involved were above 60 years of age, identified as the most knowledgeable and respected in their communities. These elders were solely men perhaps because of the patriarchal system in the Wagogo society. The technique of selecting the elders at Makulu and Ng’ong’onha was through the knowledge of our local research assistants who identified the elders for us according to the criteria we gave them: age, knowledge and respect in the community. At Ntyuka suburb, selection of one elder involved purposive sampling where we knew the elder has interests in heritage related issues.

At Makulu suburb, we conducted a focus group discussion with two elders while at Ng’ong’onha three elders were involved in the group discussion. One elder was interviewed at Ntyuka suburb, making a total of six elders involved in this qualitative research. All the elders were from the Wagogo communities. The interview conducted was semi-structured (Drever, 1995; Leech, 2002; Longhurst, 2003; Schmidt, 2004; Whiting, 2008) and this gave freedom to all participants to ask questions or express views about the questions asked. Focus group discussions took a form of single focus groups to allow interaction between a facilitating team and the elders involved in the discussion (Morgan, 1996; Nyumba et al., 2018) in the opinion gathering exercise. We requested permission from our informants to use tape recorders that allowed us to transcribe conversations from interview and group discussions at a later stage. We collected perceptions of elders about the general peopling of Dodoma, including the Wagogo communities, and specifically the presumed Wambambali people. Gaining rapport is an important consideration during interview and focus group discussions (Leech, 2002) and for this, we ensured that our informants or respondents were at ease and showed them through conversation that we valued their comments and opinions.

To enable conversations between the research team and the informants (in groups or individually), Swahili language was used as it is a common or national language in Tanzania. In some cases, however, some elders found it difficult to understand questions or convey their messages in Swahili. In this case, the local language, Cigogo, was used while others, including our local assistants, who were familiar with both languages, Swahili and Cigogo, offered translations on the scene and this was part of the recorded material. The use of the local language made it easy for the informants to give out messages that they could not say in Swahili although the defect of this strategy was for researchers to potentially lose or get some wrong information if the translation missed the concept or meaning intended by the informant.

After the interview and focus group discussions were completed, conversations from tape recorders were transferred to the computer and then transcribed in full by one of us (KPR). These transcripts were then analysed in terms of themes (Burnard, 1991) that emerged during these conversations. This approach, called thematic content analysis (Burnard, 1991), is based on grounded theory in qualitative research (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Strauss, 1987; Strauss and Corbin, 1994) and content analysis methodology of qualitative research (Mayring, 2004; Neuendorf and Kumar 2015; Drisko and Maschi, 2016).

Although our intention was to get perceptions on the Wambambali communities, several themes have emerged during the analysis of interview and focus group discussions. These range from the people preceding Wagogo in Dodoma, the origins of the current local people dominating Dodoma region (Wagogo), the meaning of Dodoma, and the Wambambali communities (including possible reasons or theories for their disappearance).

The populations preceding Wagogo and postdating Wambambali in Dodoma

In the first group discussion (held at Makulu suburb), the elders believe that the first people after the Wambambali who occupied Dodoma were called Wanyanzaga. These are thought to have been found by groups migrating from outside, especially from the southern part of Dodoma (currently Iringa and Njombe regions) who came to settle at Makulu. On the other hand, the other group (Ng’ong’onha group discussion) hints that the people found in Dodoma by migrating groups were Walewela. However, further discussion revealed that the Walewela was an early group of the Wagogo from Iringa, which migrated to Dodoma, and they are therefore part of the Wagogo people. This variance may indicate localized occupation of different parts of Dodoma, Wanyanzaga stayed at Makulu while Walewela resided at Ng’ong’onha and may have arrived at different periods. One elder at Ng’ong’onha noted that Walewela “… came from Iringa and settled here at Ng’ong’onha. There was a big forest here and the name Ng’ong’onha came from them hitting on the trees to see if there was anyone living around here and there was no reply, meaning there was nobody living in the area.” According to the Ng’ong’onha group discussion, the next people to arrive at this place (Ng’ong’onha) were Wetumba from Mpwapwa and were later followed by Wanyanzaga. In this succession story, elders have not given or estimated when these immigrations took place.

The origins of the Wagogo and the meaning of Dodoma

From the interview and focus group discussions with elders, they all indicate that Wagogo originated outside Dodoma, the region that they dominate today. There are two narratives, which emerged. One narrative is that Wagogo are a collection of ethnic groups from Iringa/Njombe who migrated to Dodoma probably due to political instabilities at their area of origin. These included the Hehe and the Bena ethnic groups. One of the elders at Makulu believes that when the Hehe arrived there (Makulu) they found pastoralist Wanyanzaga who then entered into clashes with the new comers who were farmers. In the ensuing struggle for land, the resident Wanyanzaga were driven out. He noted that “Wanyanzaga were pastoralists while the Wagogo were cultivators. Wanyanzaga grazed their cattle to the farms of Wahehe, so the Wahehe thought they should fight the Wanyanzaga because they were few and from there, they (Wagogo) dominated.” In this context, the elder creates synonymity between Wagogo and Wahehe, which as discussed below the former name is an acquired identity while the latter may be a lost identity. In this context, Wahehe are one of the ancestral groups to Wagogo. The other ethnic groups known to have created the Wagogo communities are the Nyamwezi and Kimbu from Tabora, who came to occupy the western part of Dodoma. The development of clans (known as Mbeyu in Cigogo (Rigby, 1969) within the new ‘ethnic’ group (Wagogo) was based on the area the new comers came to occupy. There are different clans and sub-clans of the Wagogo ethnic group mentioned by the elders but an exhaustive list is available in Rigby (1969). Rigby (1969:68) shows that there are about 85 clans of the Wagogo, originating from different peoples including non-Bantu groups such as Maasai. The elders in the two group discussions, Makulu and Ng’ong’onha, trace their origins to Iringa/Njombe regions while they claim that other Wagogo clans come from other directions.

The other narrative on the origin of Wagogo places them further south, in Zambia. The elder we interviewed at Ntyuka suburb firmly holds this view arguing that when ancestors of Wagogo left Zambia they arrived Mbeya where they found the Nyakyusa ethnic group who already occupied much of the land; then they proceeded to Iringa and found the Hehe and other groups already occupied that part. The Hehe urged the newcomers to proceed as there was no space for them there (somewhere in Iringa).

He reiterated that: “I want to tell you the truth; every ethnic group has a history. For us Wagogo, we came from Zambia then we arrived Mbeya and found the Nyakyusa who told us that they already occupied that place; then we came to Iringa and found the Wahehe already settled there and took all the land. So, they told us to proceed and we went until we found Ruaha River and for a long time we could not cross that river. We stumbled along the river and ran out of supplies and began eating anything around including snakes. The Wahehe eventually helped us to cross the river and then we proceeded to Dodoma.” We asked this elder why his version of origin story was different from others, and he added that “Well, because we stayed for some time in Iringa; our ancestors here (Dodoma) came to simply say that they are from Iringa but actually we are from a Wakwere ethnic group in Zambia.”

In general, the creation of the Wagogo as a new ethnic group, identity or community comes from their intermingling in the new region and, as seen below, this had implications in the political structure of the Wagogo. The Wagogo communities formed in the course of struggling to survive in the new environment, a “marginal economic environment” that Dodoma was because of having unpredictable and unequally distributed rains, recurrent droughts, floods, and famines (Rigby, 1969:1). This environment has also been called ‘inhospitable’ due to its semi-arid nature (Maddox, 1991:36). Ugogoness was then a way of life necessary for survival during precolonial and colonial times (Jackson and Maddox, 1993).

The new name (Gogo or Wagogo as used in Swahili) is a recent creation (Jackson and Maddox, 1993) that was given to them by caravan traders or their neighbours. Elders interviewed during this research at Makulu suburb held that the Nyamwezi caravan traders (between Tabora and Dar es Salaam) had a station somewhere at Kikuyu, now a suburb in Dodoma. This place had a huge log (in Swahili gogo). One elder at Makulu group discussion noted that “… when they (caravan traders) were back home, they were asked where they stayed for the night and their response in Nyamwezi was igogo and then the name Wagogo was born.” Therefore, the people living in this area were later called Wagogo (pl.) or Mgogo (sing.) in Swahili language.

The meaning of Dodoma as used today comes from the local language, Cigogo. Our informants suggested that this name Dodoma comes from a baby elephant getting stuck in the well or some water source which was situated somewhere at Kikuyu area. Because of water shortage, animals including elephants drew to this source to satisfy their thirst. In the process, one baby elephant is believed to have stuck until it died there. Other elders believe the baby elephant was swallowed up by the earth when it was stuck. Therefore, the elders’ versions of this story are variable (some think the elephant was stuck, others believe it drowned and others think it was swallowed up by the earth and mysteriously disappeared). However, from this event, the name Dodoma was born, deriving from the Cigogo language idodoma or sometimes idodomya.

We asked the elders how the Cigogo language developed and if it has any affiliation with Hehe or southern languages where most elders believe a chunk of Wagogo communities originated. Their response is that Cigogo may have some connection with the Wanyanzaga, an earlier group which was found already settled here in Dodoma instead of the original Hehe language. One of the elders in the group discussions, however, mentioned that Cigogo may be linked to a similar language spoken by a group of people currently living nearby Mikumi National Park where he has travelled and found a different people but speaking words akin to Cigogo. Hence, elders think there is no relationship between Cigogo and the Hehe language but further discussion of this is offered below.

Wambambali communities

All the elders agree that none of them have seen the Wambambali, not even their own ancestors and they believe that Wambambali existed long time before the arrival of the Wagogo. It is believed that when the first communities of the Wagogo (those from Iringa) arrived they found these deserted settlements. The elders therefore have orally transmitted stories about the Wambambali people, associated with fallen settlements scattered around the vicinities of modern settlements. All the elders have no idea of where the Wambambali originated from but some have some suggestions on where the ancient society went. In the group discussion at Makulu, one of the elders held that the Wambambali moved towards north as far as Zaire (the modern Democratic Republic of Congo) while adding that a few may have gone to Kondoa although he gave no reasons for his assumption.

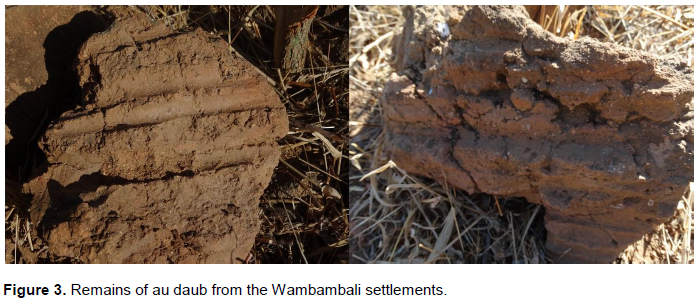

As for the Wambambali settlements, the elders made judgements based on the remnants they see and the stories passed from older generations. They believe that Wambambali made houses or structures which were set on fire before settling in to solidify the houses. These houses were made of wood and plastered by mud or daub (Figure 3), probably from bottom to the roof. One elder at Makulu group discussion noted that “They put grass on walls after it was constructed and a house was set on fire, as you can see the remains of their houses are very hard because of the burning.” Another elder added: “they (Wambambali) made houses like furnaces and set on fire so that is why you find very hard remains on surface today.” Elders believe that the burning was meant to make the house durable and more permanent.

The elder at Ntyuka suburb opined that this design of the houses was motivated by cold conditions at the time and at the same time could protect the occupants from heavy downpours that happen at times. Indeed, our observation shows that these structures were burnt before they were occupied as they indicate the same level of hardness. The Wambambali may have used wood instead of grass to burn and solidify their houses.

As none of the elders’ ancestors have presumably come in contact with the Wambambali, the generation of elders we interviewed has different theories on the demise of the Wambambali civilisation. The elders at Makulu group discussionbelieve that rain failure for successive years and hunger were the main factors for the disappearance of the Wambambali. They also added that diseases (probably infectious epidemic diseases) could have been one of the contributing factors but not an important factor. The elders at Ng’ong’onha group discussion hold no such views about the Wambambali other than that the remains of the settlements (Figure 3) around belong to this poorly known group. The elder at Ntyuka considers water shortage a significant factor as why the Wambambali left their settlements. He connects this assumption to his living memory of struggling to get water in Dodoma before the current water supply chain.

Informants at Makulu suburb argue that when the first sections of the Wagogo arrived Dodoma, they found Wanyanzaga. Mnyampala (1995) noted that different groups of people existed before the arrival of the Wagogo but succeeded the Wambambali. They included Wang’omvia, Wamankala, Wayanzi, and Wankulimba. According to Mnyampala (1995), most of these peoples were later assimilated and incorporated into the Wagogo culture. When we asked our informants about Wang’omvia and Wayanzi, they only thought they were part of the Wagogo society. The variance between the stories collected by Mnyampala and those we collected may indicate that these stories about pre-Wagogo and Wagogo communities are very old, and through time, some parts may have been eroded or forgotten. These stories, however, still serve as pointers for further investigations from other lines of evidence.

The origins of the Wagogo have been argued to be outside Dodoma and its different clans may have descended from founders originating from different ethnic groups. As claimed by elders during this research, earlier scholars also noted this claim (Rigby, 1969; Mnyampala, 1995) and some linguistic evidence places the Wagogo by Wami River at around AD 1100 (Ehret, 1984) and they may have arrived Dodoma by AD 1300 (Mnyampala, 1995). Ehret (1984) further notes that serious Bantu immigration to Dodoma somewhat increased after 1600 AD as extreme arid conditions deterred them from entering in big numbers centuries before this time. In this research, elders largely mention the influx of the migrants from Iringa/Njombe regions while noting that in the western part of Ugogo (Rigby, 1969), people from Unyamwezi came to form the Wagogo clans there. Apart from the Nyamwezi from Tabora, other groups who came to form the Wagogo clans in the western part of Ugogo/Dodoma include Kimbu, Nyaturu, Taturu and others (Rigby, 1969:11). One of the consequences of having multiple origins is the weak political cohesion or system that characterised the Wagogo for many years (Rigby, 1969). This amalgamation of different groups into a single group shows itself in how the Wagogo identify themselves. In the central part of this broad region called Ugogo/Dodoma are those who may be considered typical Wagogo while the groups living in the western part are Nyambwa and to the east are known as Itumba (Rigby, 1969) or Wetumba as narrated by our informants. Therefore, the classification of the Wagogo groups is relative to each other. For example, Wagogo in the north call all those Wagogo in the south beyond the Ruaha River Hehe while those in central Ugogo call those in the north the Sandawi and Maasai or Nyamaseya (Rigby, 1969). Such migration stories show a telescoping genealogy of the Wagogo (Rigby, 1969; Jackson and Maddox, 1993) and the continued significance of inter-ethnic relationships during colonial times meant to secure food supplies (Jackson and Maddox, 1993). Although majority of the informants believe that Wagogo clans derive from other ethnic groups from neighbouring regions (Rigby, 1969; Jackson and Maddox, 1993), one informant in this study (the elder interviewed at Ntyuka suburb) believes that the Wagogo have originated from outside Tanzania, in Zambia. This is a new claim as none of previous scholars found it from their informants. This may be an isolated case but warrants to be reported and possibly investigated further.

The general name for the people considered Wagogo came from outsiders as indicated by the current research and earlier investigations. Several versions of this story that gave the name of Wagogo exist but all point to logs (sing. gogo or pl. magogo in Swahili). In our study, the elders claimed that there were logs in the caravan station possibly used as barrier to stop caravan traders (who were predominantly the Nyamwezi) in order to collect tribute (Jackson and Maddox, 1993). Rigby (1969:20) noted that many “logs were lying about near the camp” and as a result the Nyamwezi called the local people in this area Wagogo (literal translation in Swahili is the people of the logs). Rigby (1969) does not show the purpose of this camp; whether it was a colonial or tribute collecting centre. Jackson and Maddox (1993:274–5) show that this story was given to them by the son of the last Native Authority Chief in Dodoma. This informant indicated that a local ruler near Kikombo blocked “… the path to the first water hole beyond Mpwapwa with a log …” (Jackson and Maddox, 1993:274-5) and thus, the caravans associated the people with the ‘log’ and consequently called Mgogo (sing.) or Wagogo (pl.).

The Wagogo speak Cigogo in its various dialects that reflect area variation and distance from one group to another (Rigby, 1969). Our informants do not see any link between Cigogo and the languages from their assumed ancestral areas, e.g., Hehe and Bena languages in Iringa/Njombe regions. The elders think Cigogo was generally borrowed from an already existing people in Dodoma, Wanyanzaga. In the academic literature, scholars also have different opinions as to the origins of Cigogo as a language. Guthrie (1967-1971) links Cigogo with its southern neighbours - Hehe and Bena and/or its eastern neighbours - Luguru, Sagara, and Cikaguru while Hinnebusch (1973) puts Cigogo in the Northeast Coastal Bantu. Nurse and Philippson (1975) consider Cigogo to be a sub-group in the Greater Ruvu languages although Hinnebusch (1981) doubted such a classification. It is argued that by AD 1100, the Wagogo were among the Wami peoples along the Ruvu River and migrated later further west to Dodoma (Ehret, 1984). On the other hand, Botne (1989) reconsidered the place of Cigogo within the African language groups and suggested that due to aerial, phonological, morphological, lexical, and genetic evidences, Cigogo may be a sister language to Ruhaya/Ruzinza tentatively reclassifying it as part of the J20 sub-group. We believe that Cigogo developed as a lingua franca that somehow united groups of people coming from different regions or directions to settle and find living in Dodoma.

The communities known as Wambambali are part of the pre-Wagogo history in Dodoma although oral stories show that they are more ancient than any other group preceding Wagogo. Hence, unlike other communities preceding Wagogo, our informants think that no Wagogo communities have been in contact with Wambambali people. The oral stories told by elders in our research and during Mnyampala’s (1995) time reveal that they are based on the archaeological materials scattered on the surface in some areas where Wagogo occupy today. Elders informed us that these settlements were found by the first Wagogo communities/founders who arrived in Dodoma already deserted. If the first Wagogo communities started coming to Dodoma from 1100 AD ( Ehret, 1984), it is a long time that has lapsed until now and community living memory about Wambambali may have eroded along the way or, as elders argue; none of their ancestors found Wambambali but they only found scattered material remains on the landscape.

Archaeological evidence in form of pottery remains and burnt daub fragments (Mnyampala, 1995) show that the occupation by these people was extensive, preferring to live on foothills. Ehret (1984) hinted that by 1100 AD there was a group called Kw’adza which occupied parts of Dodoma and practiced a mixed form of economy, farming and pastoralism. The Kw’adza are thought to be descendants of the formerly dominant East Rift society of Maasailand and they remained a factor in history after 1600 AD (Ehret, 1984). Maddox (1995) believes that the Wambambali people reported by Mnyampala (1995) are the Kw’adza society. Whether this judgement is correct remains to be answered by future scholarship.

Mnyampala (1995) theorised that the disappearance of this civilisation was due to foreign invasion (though invaders have not been named or identified) and mentioned the burning of daub as the evidence for that invasion. The elders we interviewed also hold different views, some thinking that water shortage was the reason for the abandonment of these settlements by the Wambambali; others believe it is rain and harvest failure for successive years that caused abandonment. As we argued previously (Ryano et al., 2020) we hold the opinion that environmental factors were at play. Although further archaeological investigation will be conducted on these settlements, we tentatively continue to suggest that crop failure due to rain shortage and consequently hunger led to the abandonment.

This research was initiated within the framework of rescue archaeology pertaining to the identification and importance of archaeological and historical heritage around the University of Dodoma, Tanzania. Research involved reconnaissance survey and test excavation with an objective to reduce the threat of destruction. In this undertaking, some issues relating to the creators of the younger cultural heritage have been investigated using qualitative survey. Hence, this synthesis was based on the information drawn from interview and focus group discussions with local elders at three suburbs, Makulu, Ng’ong’onha, and Ntyuka. We make the following conclusions about perceptions we obtained from elders.

The existence of Wagogo communities is a product of migrations that played roles in the peopling and resettlement of communities prehistorically and historically. The Wagogo founders came to environments, which other communities deserted. In the course of resettlement, some communities were assimilated by stronger ones. The founder communities of the Wagogo likely dominated local ones and the latter became assimilated.

Although Wambambali people disappeared physically leaving material evidence on the landscape, oral traditions narrated by elders of later occupants, the Wagogo, offer hints of this tradition that was spread over a wide area covering today’s Dodoma urban and surrounding rural areas including Bahi District. Changing environmental conditions, drought situation and deteriorating subsistence availability and grazing pastures may have contributed to the migration of the Wambambali out of the Dodoma region. Later cultures (the Wagogo) experienced periodic droughts and famines in this region suggesting similar situations were experienced by preceding societies including the Wambambali. Hence, future research should be oriented in examining interaction between people or cultures and studying past environments.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

This research was funded by the University of Dodoma through a Junior Academic Staff grant programme. The authors also appreciate Simon Mollel, Janeth Elimuu, Aklay Mbula, and Samson Masaka for their valuable assistance during this research and the elders for agreeing to discuss with them. They are grateful to the Antiquities Department and Dodoma Municipal authorities for permission to carry out this research.

REFERENCES

|

Botne R (1989). The historical relation of Cigogo to zone J languages. Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika 10/11:187-222.

|

|

|

|

Burnard P (1991). A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Education Today 11(6):461-466.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Drever E (1995). Using Semi-Structured Interviews in Small-Scale Research. A Teacher's Guide. Scottish Council for Research in Education.

|

|

|

|

|

Drisko JW, Maschi T (2015). Content analysis: Pocket Guides to Social Work Research. Oxford: University of Oxford Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ehret C (1984). Between the coast and the Great lakes. In Niane DT (ed.), General History of East Africa IV: Africa from the twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press and UNESCO. pp. 481-497.

|

|

|

|

|

Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. London: Aldine Transaction.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Guthrie M (1967-1971). Comparative Bantu. Farnborough, England: Gregg International Publishers.

|

|

|

|

|

Hinnebusch TJ (1973). Northeast Coastal Bantu. In. Hinnebusch TJ, Nurse D, Mould, M (eds.), Studies in the classification of Eastern Bantu languages. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag pp. 21-126.

|

|

|

|

|

Hinnebusch TJ (1981). Prefixes, sound changes, and subgrouping in the coastal Kenyan languages. Doctoral Dissertation, UCLA.

|

|

|

|

|

Jackson RH, Maddox, G (1993). The creation of identity: colonial society in Bolivia and Tanzania. Comparative Studies in Society and History 35(2):263-284.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Leech BL (2002). Asking questions: Techniques for semistructured interviews .PS: Political Science and Politics 35(4):665-668.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Longhurst R (2003). Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Key Methods in Geography 3(2):143-156.

|

|

|

|

|

Maddox GH (1995). Introduction: the ironies of Historia, Mila na Desturi za Wagogo. In. Mnyampala ME (editor's introduction), The Gogo: History, Customs, and Traditions (pp. 1-34). London: Routledge.

|

|

|

|

|

Mayring P (2004). Qualitative content analysis. A Companion to Qualitative Research 1(2):159-176.

|

|

|

|

|

Mnyampala ME (1995). The Gogo: History, Customs, and Traditions. Translated, Introduced, and Edited by Maddox GH. London: Routledge.

|

|

|

|

|

Morgan DL (1996). Focus groups. Annual Review of Sociology 22(1):129-152.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Neuendorf KA, Kumar A (2015). Content analysis. The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication pp. 1-10.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nurse D, Phillipson G (1975). The north-eastern Bantu languages of Tanzania and Kenya: a classification. University of Dar es Salaam.

|

|

|

|

|

Nyumba T, Wilson K, Derrick CJ, Mukherjee N (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 9(1):20-32.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rigby P (1969). Cattle and Kinship among the Gogo: a semi-pastoral society Central Tanzania. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Ryano KP, Mwakipesile A, Rao KS, Kasongi N, Temu E, Ngowi E, Kilonzo R (2020). Rescue archaeology at open air sites around the University of Dodoma, central Tanzania. South African Archaeological Bulletin 75(12):37-48.

|

|

|

|

|

Schmidt C (2004). The analysis of semi-structured interviews. In: Flick U, von Kardorff E, Steinke I (eds.), A companion to qualitative research (pp. 253-258). London: SAGE Publications.

|

|

|

|

|

Strauss A, Corbin J (1994). Grounded theory methodology. In. Denzin N, Lincoln Y (eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research. London: SAGE Publications pp. 273-285

|

|

|

|

|

Strauss AL (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Whiting LS (2008). Semi-structured interviews: Guidance for novice researchers. Nursing Standard 22(23):35-40.

Crossref

|

|