ABSTRACT

Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants is inadequate in Ethiopia in general, and in Chiro District in particular. Therefore, this study documents medicinal plant utilization, management and the threats encountered on them. The study was conducted from April 2017 to June 2018. Forty eight informants were purposively selected. Socio-economic and botanical data were gathered using group discussions, semi-structured interviews, and field observations and analysed using informant consensus factor, preference ranking and paired comparison methods. The result revealed that 60 plant species from 42 families and 58 genera were used as trational medicine to treat human and animal diseases. The Euphorbiaceae were represented by 7 species, followed by Asteraceae (5 species), Myrtaceae and Solanaceae (3 species each), Lamiaceae, Brassicaceae and Polygonaceae (two species each). Of the 60 species, 22 (36.67%) were herbs, followed by shrubs (n=19, 31.67%), trees (n=16, 26.66%) and climbers (n=3, 5.0%). In the study area the most significant threat to medicinal plants is agricultural expansion. Even though the study revealed that the area is enriched with medicinal plant diversity, awareness should be done to enhance the conservation of medicinal plants.

Key words: Ethnomedicine, Chiro district, medicinal plants.

World Health Organization (WHO, 2002) defines traditional medicine as ‘the the sum total of the knowledge, skills and practices based on the theories, beliefs and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether justifiable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and social discrepancy, and relying exclusively on practical experience and observation transferred from generation to generation, whether verbally or in writing’. Since traditional medicine is the most affordable, simple to use and easily accessible source of treatment, especially in developing countries (Haile and Delenasaw, 2007), it became an integral part of many cultures (Pankhurst, 1965). Studies indicate that deforestation, urbanization, agricultural expansion and lack of awareness among the community are the critical threats to medicinal plants (Hunde et al., 2015; Dida, 2017).

Ethiopia is endowed with diverse biological resources (About 6,500 are higher plants) of which approximately 10% are medicinal plants (Abera, 2014; Tadesse et al., 2018). In addition, Ethiopians have used traditional medicines for many centuries. The use of which has become an integral part of the different cultures in the country. Traditional people around the world have developed their own specific knowledge of plant resource uses, management, and conservation on which they depend on for food, medicine and general utilities (Zewudu, 2013).

According to Zewudu Birhanu (2013), traditional remedies are the source of therapeutics for nearly 70% of Ethiopian population and 90% of livestock in the country. There is, however, a need for sustainable use of medicinal plant materials and the associated indigenous knowledge as wild plants are under extreme pressure of increased demands (Haile and Dilnesaw, 2007). Moreover, in Ethiopia the use of wild or uncultivated plants is a common custom and this has been accelerating the deterioration of useful plant population in addition to agricultural expansion accompanied by wide cutting original forest species and environmental degradation (Abera, 2014). Hence, the current study aimed to document the indigenous knowledge of the local people on the use, threat and conservation of medicinal plants in Chiro district. This study has value in that it could be used as basis for further studies on medicinal plants in Chiro District and for future phytochemical and pharmacological studies.

Description of the study area

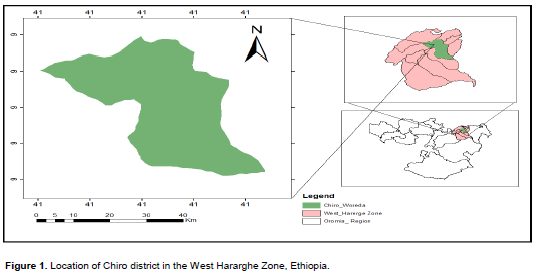

Chiro District (Figure 1) is one of the 18 Districts of West Hararghe Zone in the Oromia region of Ethiopia. Part of the West Hararghe Zone, Chiro district is located between 9°05’ longitude and 40°52’E latitude. From the study district, 6 (Medicho No.3, Nejebas, Wachu Geleyi, Gara Nigus No. 1, Medicho No. 9 and Chiro Kela) kebeles were used as sampling sites for data collection.

The district is founded at an altitude ranging from 1826 to 1950 m above sea level. The district has undulating topography and mountainous characteristics with low vegetation cover and sparsely vegetated landscapes which is highly vulnerable to erosion problems. Drought, shortage of water, soil erosion, flooding, animal forage scarcity, and lack of income diversity are the main threats to food security and sustainability. The 2007 national census reported a total population for this district of 169,912, of whom 87,003 were men and 82,909 were women; none of its population was urban dwellers (CSA, 2007). The agricultural activities are mainly mixed type with cattle rearing and crop production undertaken sideways. Major annual crops include sorghum, maize, bean, barley, teff, wheat, and pea and from cash crops Khat and Coffee are widely produced. It has a maximum and minimum temperature of 23 and 12°C, respectively and maximum and minimum rainfall of 1800 and 900 mm, respectively. Rainfall type is bimodal and erratic in nature. Main rainy season of the study area is from June to September while short rainy season is from March to May. Croton macrostachyus Del., Juniperus procera, Podocarpus falcatus (Thmb.) R.B. ex. Mirb., Vernonia amygdalina Del., and Hagenia abysinica (from the natural forests), and Juniperus procera, Cupressus lusitanica, and Eucalyptus Camaldulensis Dehnh., J.F Gmel. (from plantations) are some of the common vegetation types of the study area

Informant selection

Forty eight informants (36 males and 12 females) aged between18 to 81 were selected by using judgment and volunteer sampling techniques, according to the method of Abera (2014). Out of these, 12 (7 males and 5 females) key informants, were selected based on recommendations from elders and local authorities (Kebele administration leaders and religion leaders). These key informants were singled out due to their superior knowledge of medicinal plants over the other 36 interviewees. The informants are ethnically Oromo since they are inhabiting dominantly in the study area.

Study design

Data was collected between April 2017 and June 2018 using one-on-one semi-structured interviews, field observations, and group discussions. The semi-structured questionnaire sought to gain information on the following themes: Medicinal plants resource of the study area, preparation and administration methods of decocotions, medicinal plants species used to treat human diseases, major human diseases and plant species used for the remedies, medicinal plants species used to treat livestock diseases, major livestock disease and number of plant species used, acquisition and transfer of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants and threats to medicinal plants.

Dried specimens of the plants collected from the Chiro District were taken to the Oda Bultum University Plant Herbarium for taxonomical identification. Voucher specimens were also deposited at this herbarium.

Data analysis

A descriptive statistical method such as frequency and percentage were employed to analyze and summarize the ethnobotanical data obtained from the interviews and group discussions on reported medicinal plants and associated knowledge.

Data obtained from the questionnaire was analysed by means of quantitative statistics. Different index methods were used to analyse data on Informant Consensus Factor, as well as Preference ranking and paired comparison.

The Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) value was calculated using the formula:

ICF= (Nur-Nt)/ (Nur-1), where Nur is the number of use report of informants for each ailment, and Nt is the number of taxa used for a specific ailment (Trotter and Logan, 1986).

Preference ranking was calculated using the formula:

Preference ranking was conducted by using ten randomly selected key informants to rank four medicinal plants against Tufa being given the highest (4 = most effective) and the least (1 = less effective values to each medicinal plants species following Martin (1995).

Paired comparison was calculated using the formula:

Paired comparison was used to evaluate the degree of preference or levels of importance of 5 reported medicinal plants for treating Chancroid following Martin (1995). A list of the pairs of selected items with all possible combinations was made and sequence of the pairs and the order within each pair was randomized before every pair is presented to the 6 selected informants and their responses recorded and total value was summarized.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was sought from Oda Bultum University Ethics and Code of Conduct Committee (ECCC). Informants gave their informed consent for the publication of all results and any accompanying images before commencing with the interview schedules, as required by the Oda Bultum University Ethics and Code of Conduct Committee (ECCC).

Medicinal plants resource of the study area

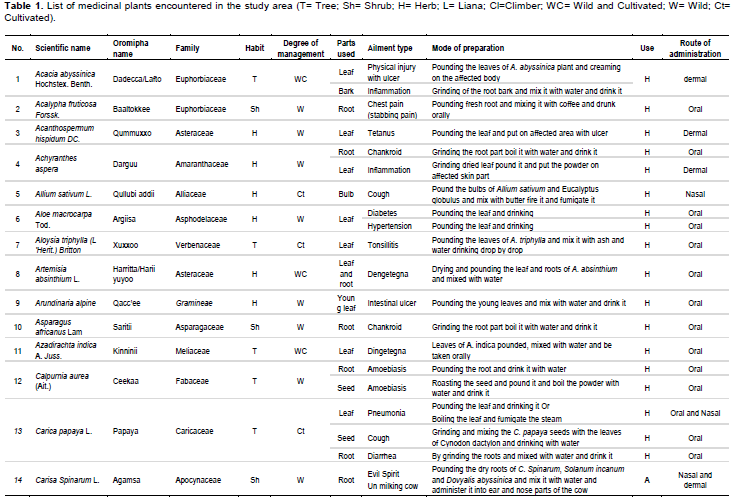

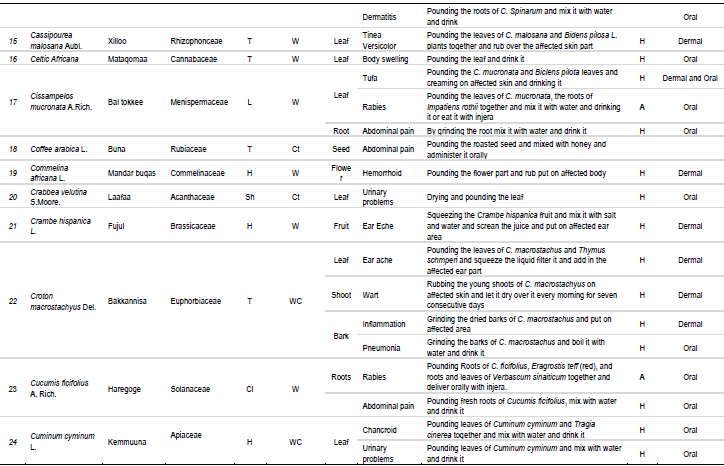

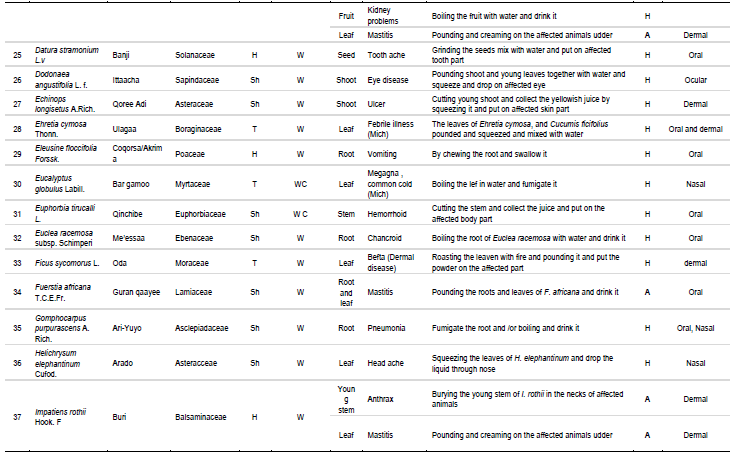

Overall, 60 medicinal plant species distributed under 42 families and 58 genera were identified in the Chiro District (Table 1). The dominant families included the Euphorbiaceae, which were represented by 7 species, followed by the Asteraceae with 5 species; Myrtaceae and Solanaceae with 3 species each, and Lamiaceae, Brassicaceae and Polygonaceae with two species each. The remaining 34 families were represented by one species each. This could be an indication that the study area consists of considerable diversity of plant species similar to other districts of the country (Kalayu et al., 2013; Zewudu, 2013; Abera, 2014).

From the total of 60 medicinal plant species documented in the study area, 39 (65%) species were wild vegetation, 11 (18.33%) species were cultivated and the remaining 10 (16.67%) were both cultivated and wild vegetation. This indicates that the practitioners mostly depend on wild vegetation than home garden vegetation for preparation of medicine which is also spported by other studies in the country (Kalayu et al., 2013; Abera, 2014; Mulugeta, 2017).

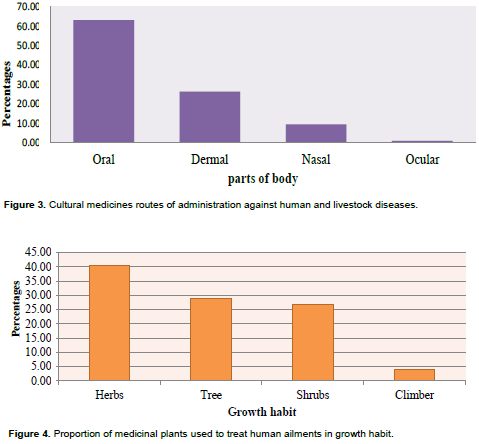

Habit

Out of 60 species, 22 (36.67%) species were herbs followed by shrubs 19 (31.67%) species, tree 16 (26.66%) species and climber 3 (5.0%) species (Figure 2). The current findings show that most widely used medicinal plants in the study area are shrubs and herb in habit. High number of shrubs and herbs for medicinal plants were explained in Ethiopia in the previous studies (Bayafers, 2000; Debela, 2001; Ermias, 2005).

Preparation of medicine

The practitioners employed 10 cultural medicine preparation methods (Table 2) to prepare 87 types of cultural medicines. From the cultural medicine preparation methods used in the study area, pounding and grinding were the most popular methods of preparation contributing to 43 (49.43%) and 15 (17.24%) cultural medicine preparations, respectively. Both pounding (Solomon et al., 2015) and grinding (Kalayu et al., 2013) methods were also reported as among the dominant cultural medicine mode of preparations. Moreover, these pounding and grinding are also importantly used by the local community to preserve the medicinal plants in the form of powder. The next ranks were taken by boiling 7 (8.05%), squeezing 6 (6.90%), chewing 5 (5.74%), smashing 4 (4.59%) etc. Others collectively constitute 7 (8.0%) preparation methods.

The current finding showed that in the study area most remedies 66 (75.86%) were prepared from single plant species while, 21 (24.14%) remedies were prepared from combined plants. This finding agrees with finding of Dawit Abebe (1986) and Debela Hunde (2001).

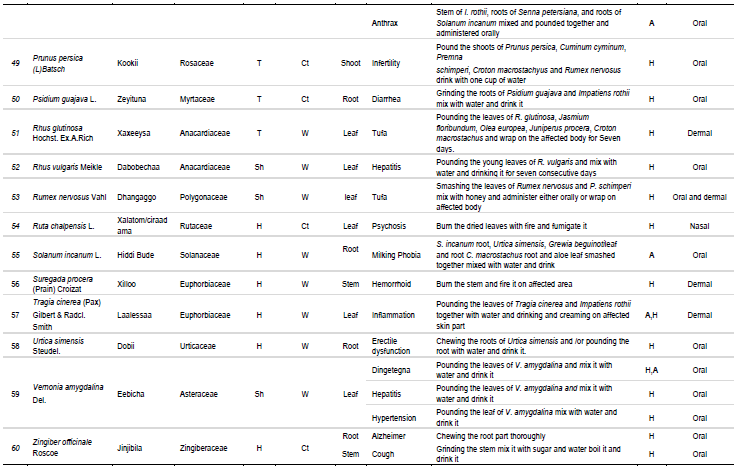

Administration methods

In the study area, various routes of administration methods (Figure 3) were employed of which, oral administrations method leads the rank [60 (63.20%)].

Next to this dermal [26 (26.32%)] and nasal [8 (9.47%)] took the 2nd and 3rd ranks, respectively. The remaining administration method was ocular 1 (1.05%). The higher employments of oral and dermal administration methods were in line with the works of Dawit and Ahadu (1993), Haile and Delnesaw (2007) and Kalayu et al. (2013).

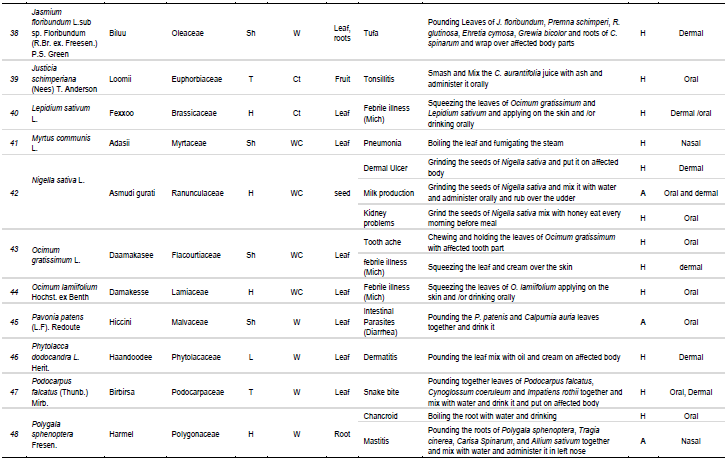

Medicinal plants used for treating human and livestock ailments

Medicinal plants species used to treat human diseases

Out of the total 60 medicinal plant species collected from the study area, 55 (91.67%) species were used to treat 39 types of human diseases. Of these 55 medicinal plant species, 48 (87.27%) species were used only for human ailments and the remaining 7 (12.73%) species were used for both human and livestock treatments.These 55 medicinal plant species comprised 39 families and 53 genera. The medicinal plants used for treatments of human ailments constitute herbs 20 (36.36%) species, tree 17 (30.91%) species, shrubs 15 (27.27%), species and Lianas 3 (5.45%) species (Figure 4). This indicates that most of the medicinal plants used for human ailments are herbs, trees and shrubs. This was in agreement with the works of Bayafers (2000) and Debela (2001).

Most (36 (65.45%) of the 55 medicinal plant species used for human aliments were collected from wild, followed by cultivated [11 (20 %) species], and wild and cultivated [8 (14.54)] species.This action has ecological meaning by the reduction of wild plant species. This finding also was explained by Mirutse (1999) and Bayafers (2000).

With regard to plant parts used, traditional practitioners mostly [31(46.96%)] harvested leaves and roots [16(24.24%)] for treating human ailments (Figure 5). The other parts include seed 5(7.58%), shoots 4 (6.06%), fruits 3(4.55%), stem 3 (4.55%) and others 4(6.06%). Studies showed that the use of leaves for medicinal purpose has little effect for rare plants in the area

However, the use of root (that is, the second mostly harvested plant part) for medicinal purpose leads to the destruction of mother plants that could affect the survival and ecological aspect of the plant (Odera, 1997; Kalayu et al., 2013).

Major human diseases and plant species used for the remedies

This study showed that a total of 39 human diseases were recorded which are treated by the 55 plant species.

The identified diseases may be treated by one or more species and vice versa. As a result, the total number of plants (71) used to treat human health in the study area were greater than the total number of medicinal plant (55) species which were documented for treatment of human disease. This clearly indicates that some plant species were used to treat more than one type of disease. For example; Carissa spinarum used to treat evil spirit, tonsillitis and snake bite. As shown in Table 4, the informants know more plant species to treat Chancroid, inflammation, fibril illness (Mich), Pneumonia, and Tufa (treated by medicines prepared from 4 and above plants each). This finding shows that about 50% of the diseases were treated with cultural medicines prepared from two or more different plant species which increases the conservation of medicinal plants.

Medicinal plants species used to treat livestock disease

Out of the total 60 medicinal plant species recorded in the study area, 12 (20%) species were used for treatment of livestock ailment. Of which 7 (58.33%) species were used for treatment of livestock and human aliments. The remaining 5 (41.67%) species were used for treatment of only livestock ailments. These 12 species were distributed under 11 families and 12 generas. Family Solanaceae represent 2 species while the remaining 10 families were represented by single species each.

These medicinal plants which were used to treat livestock comprised herbs [6 (50%)] species, shrubs 4 (33.33%)] species, and Lianas 2 (16.67%)] species (Figure 6). This indicates that, most of the plant species used to treat livestock were herbs (50%) followed by shrubs [4 (33.33%)]. This finding was in agreement with the work of Etana (2007). The remaining was liana.

The rational practitioners were familiar with using varieties of plant parts to prepare different types of traditional medicines (Figure 4). Moreover, they show certain preferences over this plant parts for their medicine preparation. In doing so, the traditional practitioners mostly used leaves from 6 (46.15%) species, roots from 5 (38.46%) species, stems and seeds from 1 (7.69%) species each. This analysis clearly showed that leaves and roots were the most important plant parts used to treat different livestock diseases followed by seed and stem parts from single plant species each in the study area. The previous study in different part of Ethiopia also showed that leaves and roots are the most important plant parts used to treat various health problems (Dawit and Estefan’s, 1991; Bayafers, 2000; Mirutse and Gobana, 2003).

Major livestock disease and number of plant species used

In the study area a total of 9 livestock diseases were recorded which are treated by the 12 plant species. The informants know more species to treat Mastitis and Anthrax.

Medicinal plant species used for both human and livestock

From the total 60 medicinal plant species recorded in the study area, 7 (3.33%) species were used for treatment of both human and livestock. These 7 species were distributed under 7 families and 7 generas. With regard to plant parts used, practitioners’ harvested leaf parts from 4 plants, roots from 3 plants, fruits and seeds from single plants each to prepare the 19 cultural medicines used to treat the 14 human and livestock diseases.

Medicinal plants use report/Informant consensus

Some medicinal plants and their utilization were more popular than others. In the study area, plant species Ocimum lamiifolium (Damakesse) took the lead where it was cited by 42 (87.5%) informants. Ruta chalpensis L. (Xalatom/ciraadama) with 41 (68%) informants and Allium sativum L. (Qullubi addii) with 40 (66.67%) informants took their consecutive ranks.

Informant consensuses factor

The frequently observed diseases in the study area probably become the primary area of concern to treat them and therefore need to accommodate more indigenous knowledge than less frequently appeared disease categories. In the current study, most of the diseases mentioned in the table have higher ICF value. This indicates the diseases which mentioned in Table 7 were common for the study area and many people have great knowledge to cure the diseases. Among the 39 diseases encountered in the study area, only 17 of them were considered. In comparison, chancroid, cough, diarrhea, tonsillitis, diarrhea, ear ache, hemorrhoid, inflammation and tufa has the highest ICF values (0.99) each followed by Alzaimer, hepatitis, hypertension, and pneumonia with ICF value 0.98 each (Table 3).

Preference ranking

The study showed that diarrhea and tufa were among the common diseases in the study area. The highest rank was given for Jasmium floribundum being as effective treatment against the disease called tufa (Table 4). Cissampelos mucronata and Rhus glutinosa took the 2nd and 3rd ranks (Table 4).

Paired comparison

Paired comparison was used to evaluate the degree of preference of 5 reported medicinal plants for treating chancroid following Martin (1995). Therefore the study identified that C. cyminum is the most preferred plant species used to treat chancroid in the study area.

Similarly, Polygala sphenoptera and Achyranthes aspera were cited as the second and third ranked plants respectively to treat Chancroid (Table 5).

Acquisition and transfer of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants

In the study area, most 36 (75%) of the informants who have acquired the knowledge on medicinal plants were from their parents and close relatives. The other 12 (12%) got the knowledge by reading different written material, by giving incentive for elders and by trial and error. Most of the informants 39 (81.25%) have already trained their family and close relatives. Some informants require incentive to give their knowledge for other person.

Threat to medicinal plants

In the study area, the survival of medicinal plants affected by both natural (dry time) and anthropogenic (fire wood, overgrazing, agricultural expansion, construction and medicine) activates. In the study area, the most threat for distraction of medicinal plants is agricultural expansion. The 2nd and 3rd threats for disappearance of medicinal plants were fire wood and dry season (Table 6).

In this study, 60 plant species with medicinal value distributed under 42 families and 58 genera were identified and documented. This shows the area is rich in plant diversity. About 39 (65%) species were found from wild vegetation, 11 (18.33%) species were cultivated and the remaining 10 (16.67%) were both cultivated and wild vegetation. Herbs were the dominant growth forms used for the preparations of traditional remedies followed by shrubs.

In the study area, 48 ailments were reported (39 for human and 9 for livestock) to be treated by traditional medicinal plants of the area. As indicated by informants, high numbers of medicinal plant species were applied for treatment of the informants know more plant species to treat chancroid, inflammation, fibril illness (Mich), pneumonia, and tufa (treated by medicines prepared from 4 and above plants) for human and mastitis and anthrax for livestock.

Humans and natural factors are the major threats to plant species in general and to the medicinal plants in particular in the study area. As suggested by most informants, in the area, the human induced threats including agricultural expansion, fire wood, construction, over grazing, and natural factors such as extended dry times were cited to be major threats for reduction of medicinal plants.

1. The indigenous knowledge and skill of traditional medicine practitioners must be encouraged and protected. This could be the way through which such people could exercise their knowledge boldly.

2. Establishing conservation measures strategies to

ensure the sustainability of multipurpose and widely used medicinal plants as most medicinal plants are obtained from the wild.

3. Create awareness of the local people on the magnitude of loss of medicinal plants and associated knowledge to ensure sustainable harvesting of medicinal plants.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

The author extends their thanks to Oda Bultum University for supporting with financial and logistic grants. They would like to express their deep sense of gratitude to the traditional healers for sharing their indigenous knowledge and invaluable time. Great thanks go to Mr. Getachew Bayable for the constructing map of the study area. The authors owe their sincere gratitude to Mr. Kaleab Terefe who gave constructive comments during the review session of the paper.

REFERENCES

|

Abera B (2014). Medicinal plants used in traditional medicine by Oromo people, Ghimbi District, Southwest Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 10:40

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bayafers T (2000). A floristic analysis and ethnobotanical study of the semi wetland of Cheffa area, South Welo, Ethiopia. M.Sc. Thesis. Addis Ababa University.

|

|

|

|

|

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (2007). The 2007 population and housing census of Ethiopia: Statistical report for Oromia Region. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

|

|

|

|

|

Dawit A (1986). Traditional medicine in Ethiopia: The Attempts being made to promote it for effective and better Utilization. SINET: Ethiopian Journal of Science ,pp. 62-69.

|

|

|

|

|

Dawit A, Ahadu A (1993). Medicinal plants and Enigmatic Health practices of Northern Ethiopia. B.S. P.E. August 1993.

|

|

|

|

|

Dawit A, Estifanos H (1991). Plants as primary source of drugs in thetraditional health care practices of Ethiopia. In: Engles JM, Hawakes JG, Malaku Worede (eds.), Plant Genetic Resources of

|

|

|

|

|

Ethiopia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 101-113.

|

|

|

|

|

Debela H (2001). Use and Management of Traditional Medicinal Plants by Indigenous People of Bosat Woreda, Wolenchiti area: An ethnobotanical approach. M.Sc. Thesis, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

|

|

|

|

|

Dida G (2017). Floristic Composition of Wetland Plants and Ethnomedicinal Plants of Wonchi District, South Western Shewa, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. M.Sc. Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa.

|

|

|

|

|

Ermias L (2005). Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants and Floristic Composition of the Manna Angatu Moist Montane Forest, Bale. M.Sc. Thesis. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

|

|

|

|

|

Etana T (2007). Use and Conservation of Traditional Medicinal Plants by Indigenous People in Gimbi Woreda, Western Wellega. M.Sc. Thesis. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

|

|

|

|

|

Haile Y, Dilnesaw Y (2007). Traditional medicinal plant knowledge and use by local healers in Sekoru District, Jimma Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 3:1-7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hunde D, Abdeta C, Sharma M (2015). Medicinal Plants use and conservation practices in Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia. Journal of Ethno Biology and Ethnomedicine 7(3):202-210.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kalayu M, Gebru T, Teklemichael T (2013). Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants used by indigenous people of Gemad district, Northern Ethiopia. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies 1(4):30-32.

|

|

|

|

|

Martin GJ (1995). Ethnobotany: A method Manual. Chapman and Hall, London, pp. 265- 270.

|

|

|

|

|

Mirutse G (1999). An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Zay People in Ethiopia. M.Sc. Thesis. Uppsala, Sweden.

|

|

|

|

|

Mirutse G, Gobana A (2003). An Ethnobotanical Survey on Plants of Veterinary Importance in Two Woredas of Southern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. SINET: Ethiopian Journal of Science 26(2):123-136.

|

|

|

|

|

Mulugeta K (2017). Diversity, knowledge, and use of medicinal plants in Abay Chomen district, Horo Guduru Wollega Zone, Oromia Region of Ethiopia. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 11(31):480-500.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Odera JA (1997). Traditional beliefs, Sacred groves and Home Garden Technologies: Adapting old practices for conservation of medicinal plants. In: Conservation and Utilization of Indigenous medicinal plants and wild relatives of food crops. pp. 19-28. UNESCO, Nairobi, Kenya

|

|

|

|

|

Pankhurst RA (1965). Historical Reflection on the Traditional Ethiopian pharmacopeias. Journal of Ethiopian Pharmaceutical Association 2:29-33.

|

|

|

|

|

Solomon A, Balcha A, Mirutse G (2015). Study of plants traditionally used in public and animal health management in Seharti Samre District, Southern Tigry, Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 11:22.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tadesse A, Kagnew B, Kebede F (2018). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human ailment in Guduru District of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy 10(3):64-75.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Trotter RT, Logan MH (1986). Informants' consensus: A new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. In Ed: Etkin NL Plants in Indigenous Medicine and Diet, pp. 91-109.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO) (2002). Traditional medicine: Growing Needs and Potentials. Geneva.

|

|

|

|

|

Zewudu B (2013). Traditional Use of Medicinal Plants By the Ethnic Groups of Gondar Zuria District, North-western Ethiopia. Journal of Natural Remedies 13(1).

|

|