ABSTRACT

Atrazine is a widely used herbicide on many crops and is considered one of water pollutant with approved biological hazards on plants, animals and human. Vicia faba seedlings as a biological system, is used to investigate the genotoxicity of Atrazine. Also, Nano selenium (N-Se), a Nano particle with reactive oxygen species scavenging activity was applied to reduce the genotoxicity of Atrazine. Atrazine treatment at concentration of 35 mg/L is applied. Two concentrations of N–Se (10 and 20 ppm) were used alone and in combination with Atrazine (35 mg/L) in addition to control treatment. Changes in germination percentage, shoot and root length, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content, lipid peroxidation product malondialdehyde (MDA), chromosomal aberrations, and mitotic index were determined. Semi quantitative RT-PCR analysis (sqRT-PCR) was applied to investigate associated changes in expression pattern of some stress related genes such as antioxidant enzymes, heat shock proteins (HSP17.9, HSP70.1), photosystem II (PSII) and Metalothioniene (MT). Atrazine treatment recorded the lowest germination percentage and caused a reduction in shoot and root length. Significant increase in H2O2 value, MDA contents, and chromosomal abnormalities percent resulted in Atrazine treatment. Noticeable suppression in expression level of all studied genes was accompanied with Atrazine treatment. N–Se, in its two concentrations with Atrazine causing a reduction in all severe effects of Atrazine and improving seedlings performance. Treatments with N–Se induced the expression of MT gene with increase in expression level alongside increase in the concentration of N-Se. This is one of rare studies that investigate the biological effects of N–Se in vivo anti-mutagenesis of Atrazine as well as a first record of Nano metalic particles N–Se as inducer for MT genes.

Key words: Nano Selenium, Atrazine, chromosomal aberrations, gene expression, Vicia faba.

In agriculture, increasing attention is paid to beneficial impacts of nanoparticles (NPs) which applied in low doses on various crops (Jampílek and Kráľová, 2017). Using of NPs can enhance plant growth, guarantee food quality and minimize the waste (García et al., 2010; Sonkaria et al., 2012; Prasad, 2014; Sekhon, 2014).

Nano–Selenium (N–Se) is recently used in the field as Nano fertilizer (Gao et al., 2002). A few studies have been published concerning the comparison between N–Se and other inorganic Se forms in higher plants (Domokos-Szabolcsy, 2011; Domokos-Szabolcsy et al., 2012). Also, less information are documented about biological effects of N–Se and its application (Chau et al., 2007; Cushen et al., 2012; El-Ramady et al., 2016). The suggested role of N-Se as reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger (Bhattacharjee et al., 2014; Sarkar et al., 2015) pointed to the possible application of this promising Nano material to remove the deleterious effects of different stresses.

Indiscriminate use of pesticides and herbicides in agriculture causes many disorders in human and animal health and do pose a potential risk to humans and unwanted side effects to the environment (Aktar et al., 2009). Atrazine (2–chloro–4–ethylamino–6– isopropylamino – 1,3,5 –triazine) is one of triazine class herbicide that is widely used to prevent emergence broadleaf and grassy weeds in variety of crops such as sorghum, pineapple, maize, sugarcane (Kumar and Srivastava, 2015). It is considered as one of the most common contaminants in ground and surface waters (Ribaudo and Bouzaher, 1994; Ali et al., 2016).

Several studies indicated the genotoxicity of Atrazine (Srivastava and Mishra, 2009). Significant increases in DNA strand breaks and frequencies of micronuclei occurred in erythrocytes of C. auratus exposed to Atrazine (Cavas, 2011). It is widely separated where it transports from the site of use to areas as far as 1,000 km via atmospheric transport and deposition through precipitation (Mast et al., 2007; Thurman and Cromwell, 2000). Atrazine ecotoxicology effects have been indicated by several studies (Song et al., 2009; Bolle et al., 2004); the European Union banned the use of Atrazine in 2004 because of its contamination of water sources (Commission, 2004)

The present study was designed to investigate the protective role of synthesized N–Se on V. faba seedlings treated with Atrazine. Our investigation tracked the associated changes in oxidative stress that occurred in the plant tissue and examining the cytological effects of the herbicide Atrazine with respect to mitotic index, chromosome aberrations and determination of changes in expression pattern using semi quantitative analysis of some stress related genes.

Experimental method and growth environments

Fifty seeds of V. faba in equal size were used for each treatment. Seeds were surface sterilized with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min. Sterilized seeds were washed with three changes of sterile distilled water and dried using sterile filter paper. The experiment was divided into six groups. One was left as a negative control where distilled water was used, while the second was considered as a positive control where 35 mg/L of Atrazine were added. The remaining four treatments received 10, 20 ppm of N–Se alone, and in combination with Atrazine.

Seeds at control and all other treatment were soaked for 24 h, and then were recovered in distilled water for one hour as recorded by Pandey and Upadhyay (2007). Germination and seedling development were carried out in five replicates of 10 seeds in a 15-cm diameter Petri dish. Petri dishes were lined with filter paper (Whatman No. 1) moistened with sterilized distilled water and incubated in dark at 25°C. The germination percentage was calculated after 24, 48 and 72 h by this formula:

Seedlings growth was measured in terms of shoot and root length (cm) after seven days of germination.

Cytological analysis

Root tips (1.5-2 cm) of germinated seeds were cut and fixed in Carnoy's fixative solution (ethyl alcohol absolute and glacial acetic acid in the ratio of 3:1) for 24 h. Root tips are kept in 70% ethyl alcohol at 4°C until it is used for cytological analysis.

Aceto–carmine stain in concentration of 2% was used for cytological preparations as described by Darlington (1976). Mitotic index, numbers and types of abnormalities were scored in at least 3000 examined cells per treatment (1000 cell/replicate) using light microscope. Mitotic index (MI) and percentage of abnormal cells were calculated using the following formulas:

Data analysis

Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software for windows version 20 were applied on obtained data for One-Way Analysis of Variance followed by Duncan test and the results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Estimation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content

Half gram of plant sample was homogenized in 5 mM of 0.1% (w/v) TCA and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min to extract hydrogen peroxide as described by Velikova et al. (2000). Ten mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 1 M potassium iodide were added to the supernatant. The absorbance of the supernatant was recorded at 390 nm. Pre-prepared standard curve was used for calculation of H2O2 content.

Evaluation of lipid peroxidation product

The concentration of TBA (thiobarbituric) -reactive products equated with malondialdehyde (MDA) was used to evaluate the level of lipid peroxidation as originally described by Heath and Packer (1968), with slight modifications as in Hendry (1993).

Extraction buffer of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Triton X-100, 2% (w/v) poly vinyl pyroolidone PVP and 1 mM AsA was used with plant sample. Two hundred microliters of supernatant were added to 0.5% TBA in 10% TCA. This solution was incubated in a 95°C water bath for 20 min followed by rapid cooling in an ice-water bath to stop the reaction. The products were quantified from the second derivative spectrum against standards prepared from 1,1,3,3–tetraethoxypropane. The amount of MDA was measured calorimetrically using spectrophotometer (UV190IPC) at 532 nm. The TBA-reactive products (MDA) were expressed as nmol.g-1DW.

Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from seedlings of control and all treated seedlings using Simply P Total RNA Extraction kit (BioFlux Cat#BSC52S1) according to manufacturer's procedure. RNA was analysed in 1.2% agarose gel with using RNase–free devices to assess RNA integrity. RNA extracts were diluted 1:10 in DEPC–treated water and RNA concentration was determined using NanoDrop spectrophotometer (BioDrop µLITE.UK). RNA purity values higher than 1.8 was considered acceptable. First–strand cDNA was synthesized using 5 μg of total extracted RNA for each sample according to the protocol supported by GoScript™ reverse transcription Kit (Promega USA) using Oligo (dT)15 primer.

Semi–quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (sqRT–PCR)

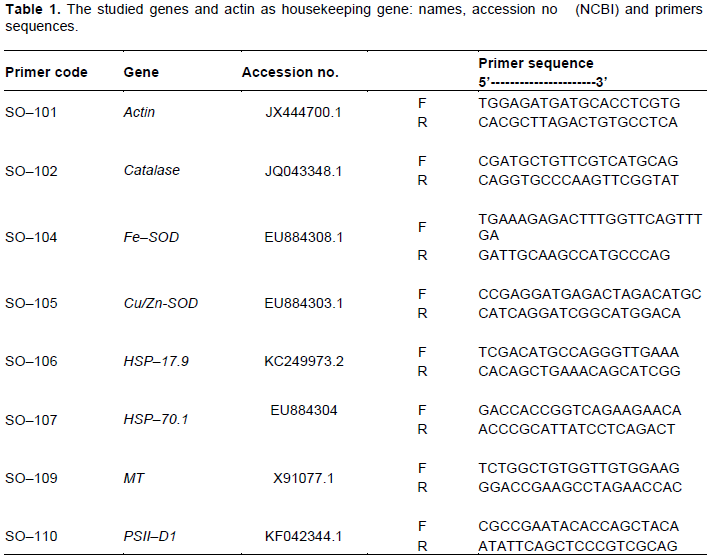

Normal PCR was used to amplify the number of copies of specific cDNA sequences in vitro. All primers used for sqRT–PCR is listed in Table 1. They were designed based on sequencing data of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from V. faba's database of selected genes on the website of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Primers were designed using the Primer Primer 5 software following the manufacturer’s guideline for primer design. Primers were ordered from Oligo Company. Samples of cDNA were standardized on actin transcript amount. Actin cDNA (accession no. JX444700.1) was used as an internal constitutively expressed control (reference gene) using gene specific primer in PCR (Table 1). For typical PCR reaction, 1 μL cDNA was used as template in 25 μL reaction volume according to instruction supported with MyTaqTM Red Mix 2x (BIOLINE). PCR program for sqRT–PCR was optimized for each gene to yield optimal contrast between samples in the fluorogrammes of subsequently performed EtBr-agarose gel electrophoresis. The general program was; 94°C for 5 min, followed by cycle of 94°C for 30 s, 55Ì° to 57°C (Table 1) for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min, and last extension step of 72°C for 5 min. Amplification products (15 µL) were electrophoresed on 1.8% agarose gel stained with EB. For assessment of the changes in gene expression of different genes, integrative density values (IDV) was determined using Totallab© v13.2 soft wear.

Effect of treatments on seed germination and seedlings growth

Data presented in Table 1 revealed that there was no significant differences in the germination percentage, the highest germination percentage of V. faba was detected after 72 h in N–Se 10 ppm, N–Se 20 ppm and Atrazine+N–Se20 compared with Atrazine which record the lowest germination percentage.

With respect to root and shoot lengths, results in Table 1 indicated that N-Se had significant effects in both 10 and 20 ppm for root length, but this effect did not differ when combined with Atrazine, the Atrazine treatment recorded the lowest value for root length.

In relation to shoot length, the data did not record significant effects and the N–Se 10 ppm showed the same value for control. From previous results, it can be concluded that N–Se (10) had the best record in both germination as well as shoot and root length. These results may be in agreement with Zhang et al. (2001) who reported that N–Se have a high biological activity, an excellent bioavailability and low toxicity.

Changes in H2O2 and MDA values

Atrazine treatment showed a significant increase in both of H2O2 (Figure 2A) and MDA (Figure 2B) contents in plant seedlings compared with control treatment. MDA is the decay product of poly unsaturated fatty acids of bio-membranes. Increasing of H2O2 and subsequently MDA contents clearly indicate the oxidative status of the cell (Omar et al., 2013). Thus, oxidative stress may be one of the potential mechanisms by which harmful effect of herbicide is occurred (Bongiovanni et al., 2012; Hassan and Alla, 2005). Increasing oxidative stress with Atrazine treatment was reported before in bean and maize (Hassan and Alla, 2005). Treatment with Ne–Se in its two concentrations caused a significant decrease in values of H2O2 and MDA contents than control values. Also, the combination addition of Atrazine with N-Se showed a significant reduction in H2O2 and MDA contents compared with treatment of Atrazine alone (Figure 2). These results showed the role of N–Se in reducing the oxidative stress of Atrazine. Decreasing oxidative stress could be a result of scavenger role of N–Se on different free radicals in vitro (Huang et al., 2003). Also, it has been reported that N–Se has a high efficiency in up-regulating seleno-enzymes (Wang et al., 2007). These results indicated that N–Se can serve as an antioxidant with reduced risk of Se toxicity (Zhang et al., 2007). Using N–Se alone or accompanied with Atrazine, causes an improvement in growth condition for plants which reflected on the growth rate in root and shoot lengths (Table 2), so it can help to reduce the severe effects of Atrazine.

Cytological effects on mitosis of V. faba root tips

Table 3 illustrated the effect of Atrazine and N–Se on mitotic index (%) and chromosomal aberrations in V. faba seedlings. Cytological analysis showed that the highest value of mitotic index (%) was scored in Atrazine+N–Se20; it showed significant (P> 5%) differences compared with negative and positive control. Application of N-Se alone did not exhibit any differences about negative and positive control but the combination between Atrazine and N–Se exhibited significant differences especially in high concentration of N–Se (Atrazine + N–Se20). In relation to chromosomal aberrations, Atrazine had genotoxic effects. The highest ratio for chromosomal aberrations compared to control and other treatments was in Atrazine, a result that agrees with Srivastava and Mishra (2009) who indicated that Atrazine may produce genotoxic effects in plants. Micronucleus, double nuclei, C–metaphase, lagging chromosome, break and disturbance were prevalent mitotic aberrations. Also, oxidative stress and DNA damage occurred on V. faba treated by Atrazine. Song et al. (2009) found significant differences after treatment with different doses of Atrazine compared to the controls in the Olive tail moments of single–cell gel electro-phoresis of root cells which are enhanced by Atrazine.

The combination between N-Se and Atrazine reduced the undesirable side effects of Atrazine; the results also indicated that the low concentrations of nanoparticles are better than the high concentrations alone or in combination with Atrazine. These results agree with the studies which indicated the protective effect of selenium nanoparticles against many materials induced cytotoxicity and genotoxicity effects, where N–Se caused significant reduction in chromosomal abnormality in bone marrow, and DNA harm in lymphocytes as well as bone marrow in mice treated with Cyclophosphamide-induced hepatotoxicity and genotoxicity (Bhattacharjee et al., 2014).

Expression patterns of selected genes

sqRT–PCR analysis showed a differential expression pattern for all selected gene (Figures 3 and 4). In general, treatment with Atrazine caused suppression in the expression of all studied genes compared with control treatment. Analysis of IDV values (Figure 4) showed that expression level of all studied genes was clearly decreased compared with control treatment. Inhibition effect of Atrazine on antioxidant enzymes were recorded in broad bean and maize (Hassan and Alla, 2005). Thus, effect on antioxidant genes (CAT, cu/zn–SOD and fe–SOD) could explain the associated increase in H2O2 and subsequently MDA contents in Atrazine treated seedling (Figure 1). Reduction in PSII expression level could be as a result of oxidative stress induced by Atrazine. PSII expression reflects the photosynthesis activity of the cell. So, the reduction in PSII expression explains the reduction in growth rate as root and shoot's length. Damaging of photosynthesis apparatus PSI and PSII under oxidation stress has been reported at many plant species (Van Breusegem et al., 1999; Allakhverdiev et al., 2000; El-Shihaby et al., 2002). Treatment with N–Se in its two concentrations induced a great increase in expression level of all studied genes compared with both control and Atrazine treatments (Figures 3 and 4). That could explain the reduction of H2O2 contents accompanied with N–Se application. Also, the addition of N–Se to Atrazine treatment reduces the suppression effects of Atrazine on gene expression of all studied genes.

Two studied HSPs genes in this study showed different responses to Atrazine, where the one with high molecular weight (HSP70.1) was more affected by Atrazine treatment than that with low molecular weight (HSP 17.9). Also, (HSP70.1) showed less response to N–Se treatment than (HSP17.9). Metallothioneins (MTs) as low molecular weight metal binding proteins showed an increase in their expression along with increasing N–Se concentrations. Increasing the expression pattern of MTs was reported in sugarcane treated with graded concentration of Se (Jain et al., 2015). This result revealed that N–Se cause an induction of MTs expression. For authors’ knowledge, this is the first investigation for ability of Nano particles to induce MTs

expression.

Our results showed that treatment with N–Se either alone or with Atrazine cause a noticeable increase in the expression level of antioxidant genes and some protected genes such as HSP17.9 gene, thus cause a reduction in oxidative stress and improve growth condition. For authors’ knowledge, this is one of rare studies that investigate the biological effects of N–Se in vivo as growth stimulator, and could be the first record for N–Se anti-mutagenesis effect of Atrazine as an herbicide widely applied on many plants.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

The authors are grateful to Prof. Hassan El–Ramady, Soil and Water Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Kafr Eelsheikh University, 33516, Egypt for the kindly support rendered with selenium nano particles.

REFERENCES

|

Aktar W, Sengupta D, Chowdhury A (2009). Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: their benefits and hazards. Interdisciplinary Toxicology 2(1):1-12.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ali I, Alothman ZA, Al-Warthan A (2016). Sorption, kinetics and thermodynamics studies of Atrazine herbicide removal from water using iron nano-composite material. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 13(2):733-742.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Allakhverdiev SI, Sakamoto A, Nishiyama Y, Murata N (2000). Inactivation of photosystems I and II in response to osmotic stress in Synechococcus. Contribution of water channels. Plant Physiology 122(4):1201-1208.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bhattacharjee A, Basu A, Ghosh P, Biswas J, Bhattacharya S (2014). Protective effect of Selenium nanoparticle against cyclophosphamide induced hepatotoxicity and genotoxicity in Swiss albino mice. Journal of Biomaterials Applications 29(2):303-317.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bolle P, Mastrangelo S, Tucci P, Evandri MG (2004). Clastogenicity of Atrazine assessed with the Allium cepa test. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis 43(2):137-141.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bongiovanni B, Konjuh C, Pochettino A, Ferri A (2012). Oxidative stress as a possible mechanism of toxicity of the herbicide 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2, 4-D). In Herbicides-Properties, Synthesis and Control of Weeds. IntechOpen.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cavas T (2011). In vivo genotoxicity evaluation of Atrazine and Atrazine-based herbicide on fish Carassius auratus using the micronucleus test and the comet assay. Food and Chemical Toxicology 49(6):1431-1435.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chau C-F, Wu S-H, Yen G-C (2007). The development of regulations for food nanotechnology. Trends in Food Science and Technology 18(5):269-280.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Commission E (2004). Commission decision of 10 March 2004 concerning the nonâ€inclusion of Atrazine in Annex I to Council Directive 91/414/EEC and the withdrawal of authorisations for plant protection products containing this active substance. 2004/248/EC. Official Journal of the European Union 78:53-55.

|

|

|

|

|

Cushen M, Kerry J, Morris M, Cruz-Romero M, Cummins E (2012). Nanotechnologies in the food industry-Recent developments, risks and regulation. Trends in Food Science and Technology 24(1):30-46.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Darlington C (1976). La cour. L. R, The Handling of Chromosomes, George Alien and Unwin, London P 182.

|

|

|

|

|

Domokos-Szabolcsy E (2011). Biological effect and fortification possibilities of inorganic selenium forms in higher plants, PhD dissertation, Debrecen University.

|

|

|

|

|

Domokos-Szabolcsy E, Marton L, Sztrik A, Babka B, Prokisch J, Fari M (2012). Accumulation of red elemental selenium nanoparticles and their biological effects in Nicotiniatabacum. Plant Growth Regulation 68(3):525-531.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

El-Ramady H, Abdalla N, Taha H S, Alshaal T, El-Henawy A, Salah E-D F, Shams MS, Youssef SM, Shalaby T, Bayoumi Y (2016) Selenium and nano-selenium in plant nutrition. Environmental Chemistry Letters 14(1):123-147.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

El-Shihaby OA, Younis ME, El-Bastawisy ZM, Nemat Alla MM (2002). Effect of kinetin on photosynthetic activity and carbohydrate content in waterlogged or seawater-treated Vigna sinensis and Zea mays plants. Plant Biosystems-An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology 136(3):277-290.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gao X, Zhang J, Zhang L (2002). Hollow sphere selenium nanoparticles: their inâ€vitro anti hydroxyl radical effect. Advanced Materials 14(4):290-293.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

García M, Forbe T, Gonzalez E (2010). Potential applications of nanotechnology in the agro-food sector. Food Science and Technology 30(3):573-581.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hassan NM, Alla MMN (2005). Oxidative stress in herbicide-treated broad bean and maize plants. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 27(4):429-438.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Heath RL, Packer L (1968). Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Archives of Biochemistry And Biophysics 125(1):189-198.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hendry GA (1993). Oxygen, free radical processes and seed longevity. Seed Science Research 3(3):141-153.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Huang B, Zhang J, Hou J, Chen C (2003). Free radical scavenging efficiency of Nano-Se in vitro. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 35(7):805-813.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jain R, Verma R, Singh A, Chandra A, Solomon S (2015). Influence of selenium on metallothionein gene expression and physiological characteristics of sugarcane plants. Plant Growth Regulation 77(2):109-115.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jampílek J, Kráľová K (2017). Nanomaterials for delivery of nutrients and growth-promoting compounds to Plants. Nanotechnology Springer, Singapore, pp. 177-226.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kumar G, Srivastava A (2015). Comparative Genotoxicity of Herbicide Ingredients Glyphosate and Atrazine on Root Meristem of Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench). Jordan Journal of Biological Sciences 8(3).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mast M, Foreman W, Skaates S (2007). Current-use pesticides and organochlorine compounds in precipitation and lake sediment from two high-elevation national parks in the Western United States. Archives of environmental contamination and toxicology 52(3), 294-305.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Omar S, Elsheery N, Kalaji H, Ebrahim M, Pietkiewicz S, Lee C-H, Allakhverdiev S, Xu Z-F (2013). Identification and differential expression of two dehydrin cDNAs during maturation of Jatropha curcas seeds. Biochemistry (Moscow) 78(5):485-495.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pandey RM, Upadhyay S (2007). Impact of food additives on mitotic chromosomes of Vicia faba L. Caryologia 60(4):309-314.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Prasad R (2014). Synthesis of silver nanoparticles in photosynthetic plants. Journal of Nanoparticles 2014.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ribaudo M, Bouzaher A (1994). Atrazine: environmental characteristics and economics of management, US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

|

|

|

|

|

Sarkar B, Bhattacharjee S, Daware A, Tribedi P, Krishnani K, Minhas P (2015). Selenium nanoparticles for stress-resilient fish and livestock. Nanoscale Research Letters 10(1):371.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sekhon BS (2014) Nanotechnology in agri-food production: an overview. Nanotechnology, Science and Applications 7:31.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Song Y, Zhu LS, Xie H, Wang J, Wang JH, Liu W, Dong XL (2009). Effects of Atrazine on DNA damage and antioxidative enzymes in Vicia faba. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 28(5):1059-1062.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sonkaria S, Ahn S-H,Khare V (2012). Nanotechnology and its impact on food and nutrition: a review. Recent Patents on Food, Nutrition and Agriculture 4(1):8-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Srivastava K, Mishra KK (2009). Cytogenetic effects of commercially formulated Atrazine on the somatic cells of Allium cepa and Vicia faba. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 93(1):8-12.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Thurman E, Cromwell AE (2000). Atmospheric transport, deposition, and fate of triazine herbicides and their metabolites in pristine areas at Isle Royale National Park. Environmental Science and Technology 34(15):3079-3085.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Van Breusegem F, Slooten L, Stassart J-M, Botterman J, Moens T, Van Montagu M, Inze D (1999). Effects of overproduction of tobacco MnSOD in maize chloroplasts on foliar tolerance to cold and oxidative stress. Journal of Experimental Botany 50(330):71-78.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Velikova V, Yordanov I, Edreva A (2000). Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Science 151(1):59-66.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wang H, Zhang J, Yu H (2007). Elemental selenium at nano size possesses lower toxicity without compromising the fundamental effect on selenoenzymes: comparison with selenomethionine in mice. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 42(10):1524-1533.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zhang J, Wang X, Xu T (2007). Elemental selenium at nano size (Nano-Se) as a potential chemopreventive agent with reduced risk of selenium toxicity: comparison with se-methylselenocysteine in mice. Toxicological Sciences 101(1):22-31.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zhang J-S, Gao X-Y, Zhang L-D,Bao Y-P (2001). Biological effects of a nano red elemental selenium. Biofactors 15(1):27-38.

Crossref

|

|