ABSTRACT

Adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution using a low cost Sclerocarya birrea fruit shell powder based biosorbent was investigated in a batch system. Results showed that optimum adsorption capacity was achieved at pH 8 and biosorbent dosage of 0.6 g, with a maximum adsorption capacity of 27.690 mg g-1. Equilibrium studies showed that experimental data fitted well on the Temkin isotherm (R2 = 0.9641), as well as the Langmuir isotherm (R2 = 0.9626). The adsorption process followed the pseudo-second order rate kinetics with R2 values greater than 0.999. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectrum showed the presence of absorption bands typical of a plant based biomaterial. Given the abundant availability of the S. birrea trees in Southern Africa, the seed fruit shell can be used as a source of low cost biosorbent.

Key words: Biosorption, Langmuir, methylene blue, Sclerocarya birrea fruit, Temkin.

Industrialization and urbanization, despite having contributed to improved living standards, have resulted in high levels of pollution in water bodies. Effluent dyes have been identified as one of the major sources of pollution in municipal waters. Wastewater from pulp and paper, tannery, textile, food, pharmaceutical and electroplating industries contains high levels of synthetic dye pollutants. These high levels of dye pollutants must be reduced below regulatory limits. Literatures suggest that there are more than 10,000 different types of synthetic dyes on the world market, with a combined annual production of 7 × 105 tons (Mohammed et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2003; Daneshvar et al., 2007; Aksu and Karabayır, 2008; Hameed et al., 2008). The manufacture of dyes and its application in the textile industries generate large volumes of effluent dyes, and this presents a great challenge in the treatment of such wastewaters (Joshi et al., 2004; Anjaneyulu et al., 2005; Kushwaha et al., 2014).

Synthetic dyes as water pollutants are a serious threat not only to human health but also to aquatic life. Health risks such as cancer development, mental confusion, tissue necrosis and a host of physiological disorders have been linked to exposure to high levels of synthetic dyes (Mathur et al., 2005; Puvaneswari et al., 2006). Effluent synthetic dyes also affect light penetration which is not conducive for aquatic life.

Despite the existence of a number of water effluent treatment technologies, challenges still exist. Some of these challenges include incomplete removal of dye and generation of secondary pollution (Babu et al., 2007). These established technologies include various biological and chemical treatment methods, adsorption, reverse osmosis and membrane filtration methods (Ong et al., 2011). One of the ways of controlling pollution is the introduction of a number of policies by water authorities in both developed and developing countries. There are, despite the benefits, challenges of monitoring and implementation especially in developing countries, mainly due to associated costs (Wang et al., 2008; Blackman, 2010).

Of the adsorption techniques that are being continuously developed, biosorption has attracted a lot of research interests due to its renewable and low cost nature (Choudhary et al., 2015; Hameed and Ahmad, 2009). This study reports a biosorption approach for the removal of methylene blue from water effluent using a renewable natural adsorbent, Sclerocarya birrea fruit seed shell powder. S. birrea is a naturally growing tree in Southern Africa (Neo et al., 2011). The fruits have a number of commercial uses and have been used to sustain livelihoods of indigenous population in Southern Africa (Wynberg et al., 2003; Jama et al., 2008). The shell is a by-product of fruit processing or consumption.

Preparation of adsorbent

S. birrea fruit seed shells were harvested from a forest in the Chibi District of Masvingo Province in South Western Zimbabwe. The shells were washed with distilled water before being dried at 50°C overnight. The dried seed shells were ground into a fine particulate powder and were sieved through a 75-micron sieve. The powder was used for adsorption experiments without further treatments. The FTIR spectra of the powdered fruit seeds shell was recorded on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS5 MIR FTIR spectrophotometer equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory and OMNIC software.

Adsorption experiments

Methylene blue solutions of 20, 40, 60 and 80 mg L-1 were prepared by serial dilutions from a 1000 mg∙L-1 stock solution. In a 50 ml solution, 0.6 g of biosorbent was suspended and agitated at 200 rpm under pre-determined conditions. The concentration before and after adsorption experiment were determined using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Genesy 10S UV/Vis spectrophotometer measured at 664 nm. Adsorption parameters were optimized in terms of contact time, pH, and biosorbent dosage. Removal efficiency (RE) and adsorption capacity at equilibrium was calculated using Equations 1 to 3, respectively.

Where, C0 is the initial dye concentration in mg L-1, Ct is dye concentration at time t, qt is the adsorption capacity at time t, qe is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium, Ce is the concentration at equilibrium, V the volume of dye solution and M the mass of biosorbent.

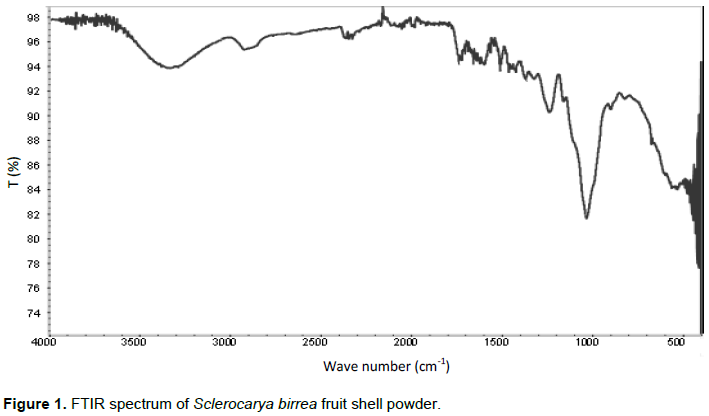

FTIR spectrum

The FTIR spectrum of biosorbent powder is shown in Figure 1. A broad absorption band with peak maxima at 3334 cm-1 can be attributed to -OH stretching vibration. The band may also overlap -NH stretching vibrations and the amino group. A small but sharp absorption band at 1735 cm-1 can be attributed to the carbonyl group while strong absorption band is associated with a C-O-C stretching vibration. These IR absorption bands are typical of a number of plant biomaterials (Pavan et al., 2008; Song et al., 2011; Samiey and Ashoori, 2012; Hassan et al., 2017).

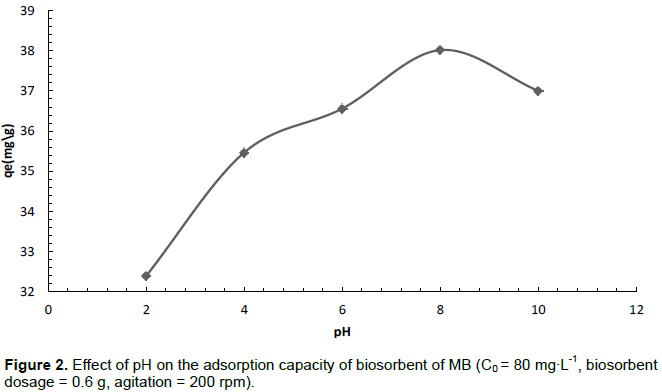

Effect of pH

The effect of sorbate solution pH on biosorption capacity was determined within the pH range of 2 to 10. The results are illustrated in Figure 2. It can be observed from the diagram that the biosorption capacity steadily increased to maximum adsorption capacity of 37.001 mg g-1 at pH 8 and fell drastically thereafter. A decrease in biosorption capacity below pH 8 can be attributed to increase in protonation of adsorption sites resulting in the repelling of diprotonated methylene blue molecules. A similar trend has also been observed for the biosorption of methylene blue by meranti sawdust based biosorbent (Ertugay and Malkoc, 2014; Ahmad et al., 2009).

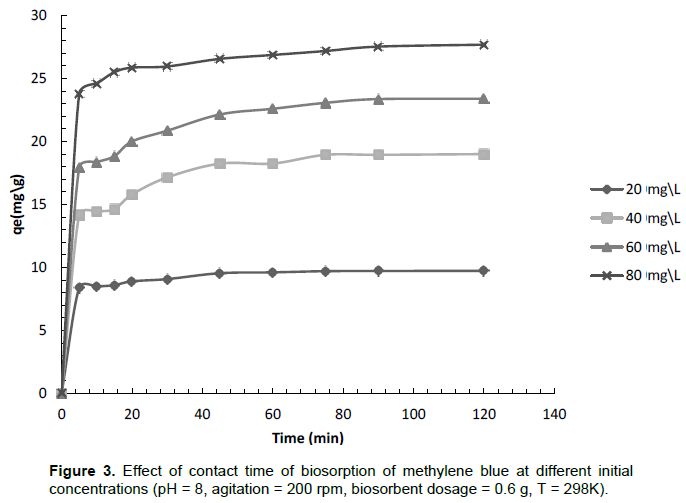

Effect of contact time

Contact time parameter is an important parameter in the optimization of an adsorption process. The effect of contact time for initial concentrations 20, 40, 60 and 80 mg L-1 was monitored over 90 min and the result is illustrated in Figure 3. The diagram shows that for all initial concentrations, equilibrium was quickly reached in less than 10 min and this is mainly due to available adsorption sites. A biosorption process where equilibrium is quickly reached has also been observed using a brown alga based biosorbent (Caparkaya and Cavas, 2008).

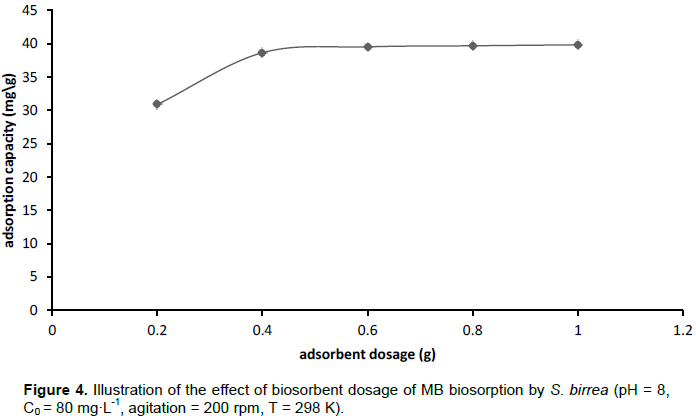

Effect of biosorbent dosage

The effect of biosorbent dosage was determined for the dosage range of 0.1 to 1.0 g suspended in 50 ml of dye solution. The result is illustrated in Figure 4. From the figure, it can be observed that removal efficiency increased up to a dosage of 0.5 g and no increase was observed at higher dosages. The observed trend has been attributed to the fact that at higher dosage, the effective surface area available for biosorption decreased as a result of aggregation (Guo et al., 2014; Barka et al., 2011).

Adsorption isotherm studies

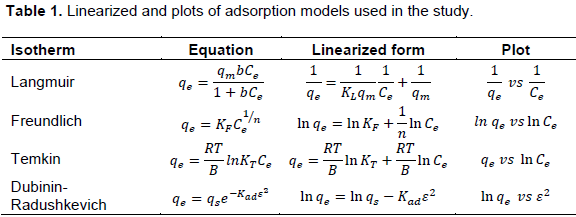

Many empirical models have over the years been developed, but in this study, experimental data was fitted onto the Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin and Dubinin-Radushkevick isotherms. The Langmuir adsorption isotherm model, the most common of all the models, assumes that the adsorbent has finite sites per unit mass that can be occupied by adsorbate molecules. The model assumes a monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface and that there is a finite number of identical sites (Langmuir, 1916). An expression of Langmuir adsorption isotherm is shown in Equation 4.

Where, qm is the maximum adsorption capacity in mg g-1, qe is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium and KL is the Langmuir constant in L mg-1.

The Freundlich adsorption isotherm assumes a multi-layer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface. The isotherm is an exponential equation expressed as shown in Equation 5.

Where, KF is the Freundlich constant in and is an indication of relative adsorption capacity of the adsorbent while n is a constant indicating the intensity of adsorption.

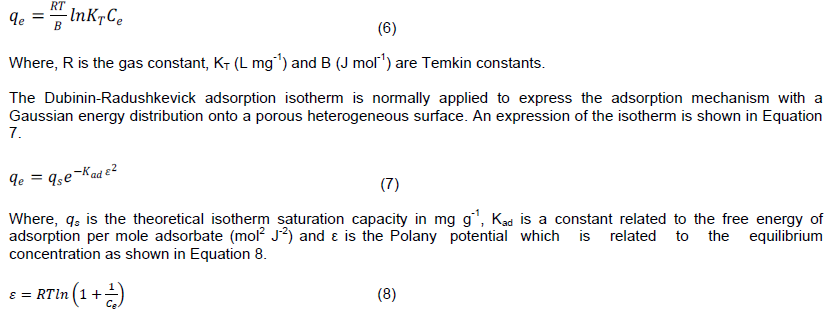

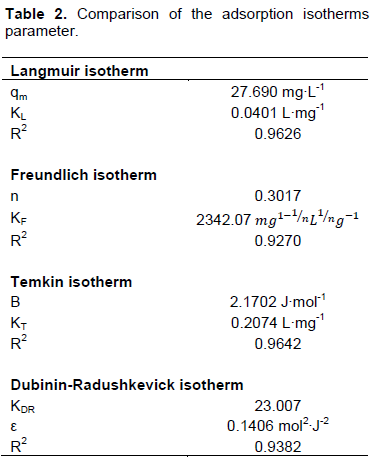

The Temkin isotherm was developed to take into account the effect of indirect adsorbent-adsorbate interactions on adsorption (Temkin, 1941). It postulates that the heat of adsorption of the layer would decrease linearly with coverage due to these interactions. The Temkin isotherm is expressed as shown in Equation 6.

The linearized forms and plots are summarized in Table 1. The results for fitting experimental data onto the isotherm models are summarized in Table 2. A comparison of the R2 values suggests that the data fitted well onto the Temkin isotherm, as well as the Langmuir isotherm. A biosorption study with Xanthoceras sorbifolia seed coat based biosorbent also produced a similar result (Yao et al., 2009).

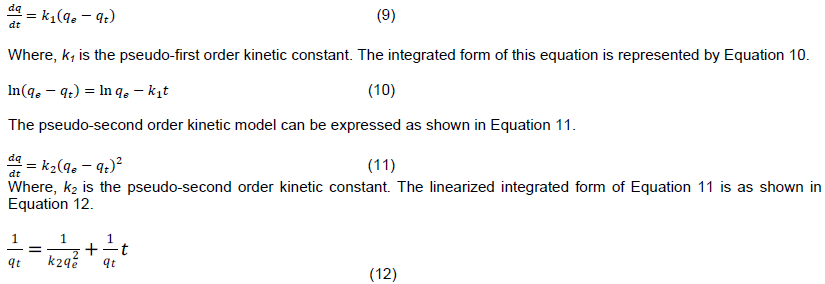

Kinetic study

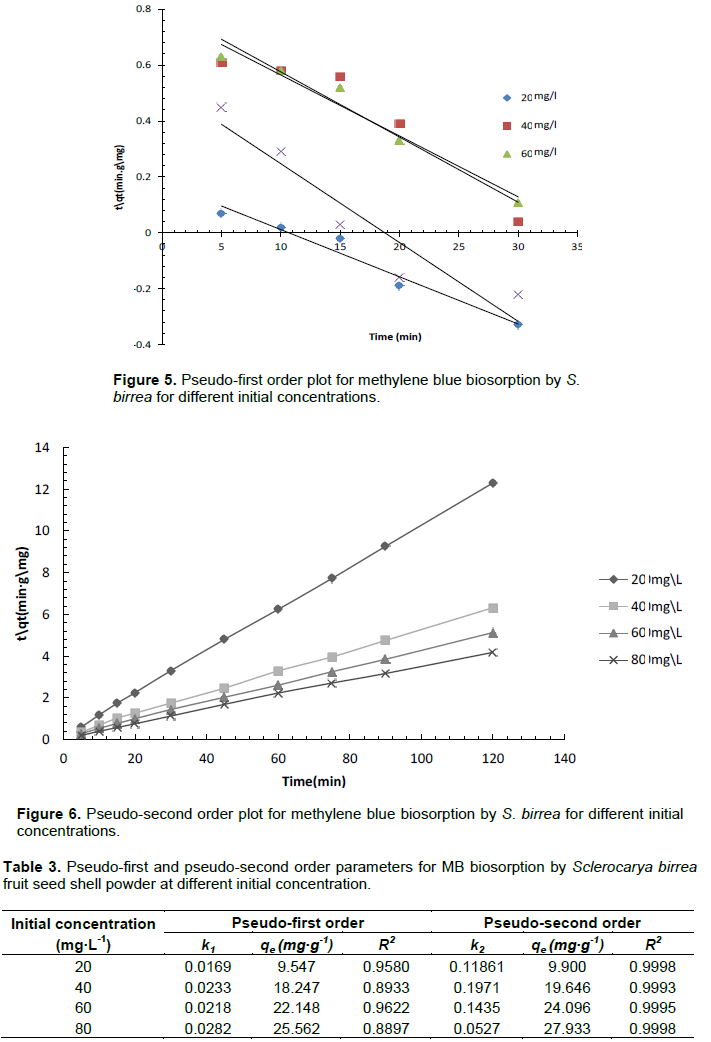

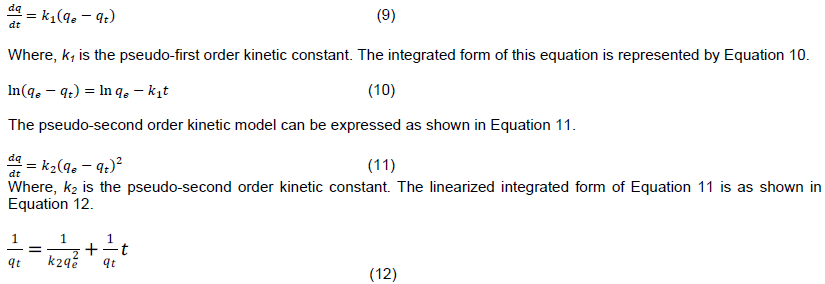

Kinetic parameters are important in optimizing an adsorption process. Experimental data for methylene blue biosorption by S. birrea was fitted on the pseudo-first and pseudo-second order kinetic models. The pseudo-first order kinetic model is represented by Equation 9.

The parameters k2 and qe can be obtained from the intercept and the slope of versus t, respectively. The results for pseudo-first and pseudo-second order plots are illustrated in Figures 5 and 6, respectively. A summary of pseudo-first order and pseudo second order parameters is shown in Table 3. From the R2 values, it can be concluded that the biosorption process followed more the pseudo-second order kinetic rate than the pseudo-first order rate. A number of studies on biosorption of methylene blue with different biosorbents suggest that adsorption kinetics tend to be more of pseudo-second order rate than pseudo-first order rate (Mitrogiannis et al., 2015; El Sikaily et al., 2006; Hamdaoui and Chiha, 2007; Ahmad et al., 2009).

The study demonstrated that S. birrea was a potentially effective biosorbent for the removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions. A maximum adsorption capacity of 27.690 mg g-1 was achieved at an optimum pH 8. Given the abundant availability of the S. birrea trees in Southern Africa, the seed fruit shell can be used as a source of low cost biosorbent.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ahmad A, Rafatullar M, Sulaiman O, Ibrahim MH, Hashim R (2009). Scavenging behavior of meranti saw dust in the removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 170:357-365.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Aksu Z, Karabayır G (2008). Comparison of different kinds of fungi for the removal of Gryfalan Black RL metal complex dye. Bioresour.Technol. 99:7730-7741.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Anjaneyulu Y, Chary NS, Raj DSS (2005). Declourization of industrial effluents – available methods and emerging technologies – a review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 4(4):245-273.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Babu BR, Parande AK, Raghu S, Kumar TP (2007). Cotton Textile Processing: Waste generation and effluent treatment. J. Cotton Sci. 11:141-153.

|

|

|

|

|

Barka N, Abdennouri M, El Makhfouk M (2011). Removal of methylene blue and eriochrome black T from aqeous solutions by biosorption on Scolymus hispanicus L. Kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamics. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 42:320-326.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Blackman A (2010). Alternative pollution control policies in developing countries. Rev. Environ. Econ. Pol. 4(2):234-253.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Caparkaya D, Cavas L (2008). Biosorption of methylene blue by a brown alga Cystoseirabarbatula Kützing. Acta Chim. Slov. 55:547-553.

|

|

|

|

|

Chen KC, Wu JY, Liou DJ, Hwang SCJ (2003). Decoloration of the Textile dyes by newly isolated bacterial strains. J. Biotechnol. 101:57-68.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Choudhary P, Singh J, Subramanian S (2015). Biosorption of acidic dye from aqueous solution by a marine bacterium, Planocuccus sp. VITP21. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 8(4):1763-1968.

|

|

|

|

|

Daneshvar N, Ayazloo M, Khataee AR, Pourhassan M (2007). Biological decoloration of dye solution containing Malachite Green by microalgae Cosmarium sp. Bioresour. Technol. 98(6):1176-1182.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

El Sikaily A, Khaled A, El Nemr A, Abdelwahab O (2006). Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution by marine green alga Ulvalactuca. Chem. Ecol. 22(2):149-157.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ertugay N, Malkoc (2014). Adsorption isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies for methylene blue from aqueous solution by needles Pinis sylvestris L. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 23(6):1995-2006.

|

|

|

|

|

Guo JZ, Li B, Li L, Lv K (2014). Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions by chemically modified bamboo. Chemosphere 111:225-231.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hamdaoui O, Chiha M (2007). Removal of methylene blue from aqueus solution by wheat bran. Acta Chim. Slov. 54:407-418.

|

|

|

|

|

Hameed BH, Ahmad AA (2009). Batch adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution by garlic peel, an agricultural waste biomass. J. Hazard. Mater. 164:870-875.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hameed BH, Mahmoud DK, Ahmad AL (2008). Equilibrium modelling and kinetic studies on the adsorption of basic dye by a low-cost adsorbent: coconut (Cocos nucifera) bunch waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 158:65-75.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hassan W, Farooq U, Ahmad M, Athar M (2017). Potential biosorbent Heloxylon recurvum plant stems for the removal of methylene blue dye. Arab. J. Chem. 10:S1512-S1522.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jama BA, Mohamed AM, Malatya J, Njui AN (2008). Comparing the "Big Five": A framework for the sustainable management of indigenous fruit trees in the dryland of East and Central Africa. Ecol. Indic. 8(2):170-179.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Joshi M, Bansal R, Purwar R (2004). Colour removal from textile effluents. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 29:234-259.

|

|

|

|

|

Kushwaha AK, Gupta N, Chattopadhyaya MC (2014). Removal of methylene blue malachite green dyes from aqueous solutions by waste material of Daucus carota. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 18(3):200-207.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mathur N, Bhatnagar P, Bakre P (2005). Assessing mutagenicity of textile dyes from Pali (Rajasthan) using AMES bioassay. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 4(1):111-118.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mitrogiannis D, Markou G, Celekli A, Bozkurt H (2015). Biosorption of methylene blue onto Arthrospira platensis biomas: Kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 3(2):670-680.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mohammed MA, Shitu A, Ibrahim A (2014). Removal of methylene blue using low cost adsorbent. A review. Res. J. Chem. Sci. 4(1):91-102.

|

|

|

|

|

Neo CM, Ding YF, Moffat PS, Ma C, Liu YJ (2011). The importance of an indigenous tree to southern African communities with specific reference to its domestication and commercialization: A case of the marula tree. For. Stud. 13(1):36-44.

|

|

|

|

|

Ong ST, Keng PS, Lee WN, Ha ST, Hung YT (2011). Dye waste treatment. Water 3:157-176.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pavan FA, Lima EC, Dias SLP, Mazzacuto AC (2008). Methylene blue biosorption from aqueous solutions by yellow passion fruit waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 150:703-712.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Puvaneswari N, Muthukrishnan J, Gunasekaran P (2006). Toxicity assessment and microbial degradation of azo dyes. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 44:618-626.

|

|

|

|

|

Samiey B, Ashoori F (2012). Adsorptive removal of methylene blue by agar: effects of NaCl and ethanol. Chem. Cent. J. 6:14.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Song J, Zou W, Bian Y, Su F, Han R (2011). Adsorption characteristics of methylene by peanut husk in batch and column modes. Desalination 265:119-126.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Temkin MI (1941). Adsorption equilibrium and kinetic of processes on non-homogeneous surfaces and in the interactions between adsorbed molecules. Zh. Fiz. Chim. 15:296-332.

|

|

|

|

|

Wang M, Webber M, Finlayson B, Barnett J (2008). Rural industries and water pollution. J. Environ. Manage. 86:648-659.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wynberg RP, Laird SA, Shackleton S, Mander M, Shakleton C, Du Plessis P, Den Adel S, Leaky RRB, Botelle A, Lombard C, Sullivan C, Cunningham T, O'Regan D (2003). Marula commercialization for sustainable and equitable livelihoods. For. Trees Livelihoods 13:203-215.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yao Z, Wang L, Qi L (2009). Biosorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution using bioenergy forest waste: Xanthocerassor bifolia seed coat. Clean 37(8):642-648.

|

|