The main objective of this study was to evaluate the contribution of activated carbon, based on coconut shell, in the treatment of mangrove and well contaminated water from the BONAPRISO district. More precisely, it consisted of preparing the activated carbon, then characterizing the mangrove water and the well water through a manual of sampling procedure; and finally verifying that the activated carbon produced had a good capacity for absorption of bacteria contained in the different sampled waters. Therefore, it emerged from this study that the activated carbon produced from coconut pods carbonized at 561°C, ground and activated at 443°C, had a specific surface of 658 m2/g and pore sizes of 20 µm. Thereafter the various waters characterized showed a yellowish coloration for well water and whitish for mangrove water, a pH ranging from 6.5 and 6.8, respectively; and the total flora had a total load of 2.18×105 CFU/ml for well water and a total load of 3.24×105 CFU/ml for mangrove water. Finally, the effectiveness of activated carbon in fixing bacteria, such as total flora, streptococci, and faecal coliforms showed that it was adsorbed in well water: 86.45% total flora; 91.67% streptococci; 100% faecal coliforms, and therefore, acted at 92.7%. Similarly, in mangrove water, there is 51.22% of total flora, 100% streptococci, and 92.4% faecal coliforms were fixed and, therefore, acted at 81.20%. The remaining bacteria, in well water (13.55% total flora; 8.33% streptococci) and in mangrove water (48.78% total flora; 7.6% faecal coliforms), respectively, could not be fixed.

Water has been an essential resource in human life and its environment for decades. It is incumbent that this is a natural need either for consumption or for current use. So if it is contaminated with pathogens or other toxic elements, it will immediately lead to diseases or the death of certain plants. These contaminating substances can

come either from the physical environment in which the water has evolved, or from the releases of certain human activities of which the water has become the receptacle (Kanohin et al., 2017). Long-term risks are linked to poor physico-chemical quality (pollution resulting from technological and industrial development), while short-term risks are linked to microbiological characteristics (Kuitcha et al., 2010; Njoku et al., 2014). Water, as a reservoir of germs, constitutes an essential link in the transmission of digestive tract infections (Ndjama et al., 2008). The quality of bathing water was sometimes assessed by researchers through the isolation of coliphages and bacteriophages (Palmateer et al., 1991; Katte et al., 2003; Chun-Han et al., 2011; Caitlin et al., 2014). That of water for human consumption has been studied by other researchers who isolated the bacteria that control faecal contamination (bio-indicators) such as faecal coliforms and faecal streptococci. However, only few studies had been carried out on the characterization of surface water in the equatorial zone where there is an abundance of water. Moreover, in the cities of this climatic zone, especially in poor urban areas where the habitat is spontaneous, the traditional latrines are very shallow and rub shoulders with water points. It should also be noted that some families empty their septic tanks directly into the drains during the heavy rains, especially in cities where there is a significant amount of water (Djuikom et al., 2009; Akoachere et al., 2013). Wells and mangroves, for example, are the most affected because they are the receptacles of this wastewater, which affects them with important pathogens or toxic agents (Jamieson et al., 2004).

The objective of this work was, therefore, to assess the contribution of activated carbon in the treatment of mangrove water and well water from the BONAPRISO district in Douala. More specifically, it was a question of producing the activated carbon based on coconut pods, then doing a bacteriological analysis of the mangrove water and the well water by filtration of the activated carbon produced.

Sampling site

The sampling site was in the BONAPRISO district in Douala (Cameroon) where KEMIT ECOLOGY was located (Figure 1).

Coal preparation, sampling and experimentation

Sampling, filtration, and analysis of the results were carried out in the structure. Thus, the well and the mangrove sources were the two types most frequently used by the populations of this district.

Preparation of activated carbon

For the utility, 16.2 kg of pods were imprisoned in coconuts in barrels, embers of fire added and the barrels closed with their tight lids. All of the barrels were placed in a closed enclosure protected from oxygen. The heat exchanges inside each barrel transformed the material (coconut pods) into inactive carbon or carbon; this was the carbonization process. The carbonization parameters were variable and measurable (initial temperature and its evolution), and the initial masses were known. All the charred pods were recovered after cooling, crushed, and sifted until carbon powders with a diameter of less than 5 mm were obtained. The coal powders were then subjected to an artisanal physical activation which consisted of using a semi-adiabatic muffle (Njoku et al., 2014).

Sampling

Taking the mangrove water samples, the sampling was done through the wading sampling protocol which describes how the samplers must enter the watercourse, the place from which the sample should be taken, as well as how to collect a sample (Figure 2) while minimizing the risk of contamination (CCME, 2011).

Taking samples of well water, which were assimilated to the protocol for sampling the water column from a bridge, and also describes how the samples should be attached, where the sample should be taken, and how to carry out sampling to minimize the risk of contamination, from the road surface or the bridge structure, were strictly observed (Figure 3) (CCME, 2011).

Preservation and preparation of samples

The manual and general safety protocols relating to the preservation of samples in the field were used to preserve and the samples were prepared. The sample was kept in a cooler with ice cream, and then stored in a refrigerator. Then the sample was treated according to the solutes sought and analysis technique was used. However, a prior filtration step is common and was carried out on a coffee filter in order to remove debris or other impurities (Tita et al., 2009).

Water filtration and bacteriological analysis of sampled water

The water filtration was done through a manufactured prototype (Figure 4) container, among other things: cotton fabric or cotton; activated carbon; fine sand; small pebbles; medium pebbles; large stones; and water sampled.

As for the bacteriological analysis, it will relate to bacteria such as streptococci and faecal and total coliforms; and the total flora, because they are responsible for several diseases in humans. The method consisted of quantifying these microbes present in the water samples taken in the laboratory and it was done as follows: the respective culture media were the BEA for streptococci (quantities: 56.6 g/1 L); and Endo for coliforms (quantities: 23.5 g/1 L) which was dissolved by heating. Then followed the preparation of the physiological waters for the inoculated in the samples (9 ml of physiological water for 1 ml of sampled water); finally, they were put in an oven at respective temperatures of each microbe for 3 days in order to count them.

Preparation of activated carbon

Carbonization

Carbonization is the chemical transformation of dry vegetable matter under the action of heat and oxygen from the air into carbon black powder. During this process of converting dry matter into carbon black powder, there is a release of greenhouse gases, water vapour, uncondensed oils, and volatile organic matter (Yaning et al., 2019).

where xt are the residues of thermolysis only identifiable to X-ray diffraction.

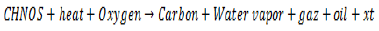

The results show that the carbonization lasted 57 min for temperatures ranging from 166 to 561°C, in the context of the study. It took place in three phases. The ignition corresponded to the ignition of the fire in the pods and its duration was 16 min and its ignition temperature is 199°C. The carbonization proper which was the coal production phase had a duration ranging from 16 to 57 min for carbonization temperatures ranging from 166 to 561°C; jet cooling of 1.3 kg of water cooled the coal where a temperature of 41°C was obtained (Hatem et al., 2014).

Thus, the coal obtained weighed 3.65 kg after carbonization of 16.2 kg of coconut pod, the yield obtained was, therefore, Ro = 22.53%, and subsequently, 90 g of ground material for activation were used in the study (Figure 5).

The coconut pods had undergone carbonization for a duration of 57 min at a final temperature of 561°C; on the other hand, activation had a duration of 3 min for a final activation temperature of 443°C. However, according to the work of Daud and Ali (2004), the activation temperature of coal based on these same pods and having undergone the same principle of carbonization is 800°C for a period 2 h. This variation was due to the fact that:

(1) There was a loss of energy during carbonization, because the metal oven was exposed to air, which increased the rate of ash in the coal, and reduced the temperature and the duration of activation;

(2) The conditions of physical activation were not the same; they activated in a centrifuge devoid of air, and were hermetically closed;

(3) Daud and Ali (2004) used carbon dioxide (CO2) in their carbonization reaction medium to prevent the calcination of coconut pods after 443°C. These results are, therefore, in contradiction because of the conditions of the reaction medium.

(4) State-of-the-art equipment for optimal activation conditions were deployed in their study: a sterilized pot and a gas plate for heating. But for the researcher’s activation, this took place in the laboratory in a thermo-programmable oven.

(5) The duration and the temperature submitted in our study could not be in excess because the activated carbon would be reduced to ash.

In the present research, their temperature was maintained by the presence of CO2 for a contact time of 2 h which would reduce the O2 present in the oven (reduction instead of oxidation) so that the carbon did not reduce in ash, which was not our case.

Activation

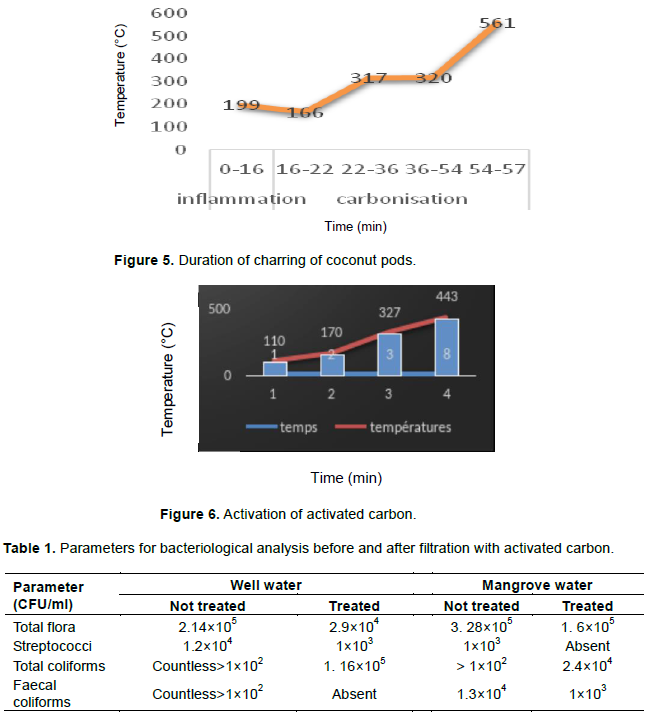

Activation consisted of increasing the specific surface and increasing the size of the coal pores during a given period and temperature. Figure 6 shows the different temperatures and time recorded during the activation of said carbon.

The results show that the activation lasted 8 min at temperatures between 110 and 443°C, temperatures taken at the centre of the hot plate. And the mass obtained after activation was 41.3 g for an activation rate of 73.75%:

(1) The temperature 110°C corresponded to the temperature of the plate taken directly after the lighting of the fire;

(2) From 110 to 170°C activation was started, corresponding to roasting of coal;

(3) From 170 to 443°C, the actual activation took place, which corresponded to the release of tar pores and other compounds (organic matter, ash);

(4) The temperature 443°C marked the end of the activation by extinguishing the fire.

Specific surface and pore size

Adsorbent used for carrying out tests for the elimination of bacteria is an activated carbon (Riddel-de Haen) with a pore size of 20 μm and a specific surface of 658 m2/g (Emanuele et al., 2012).

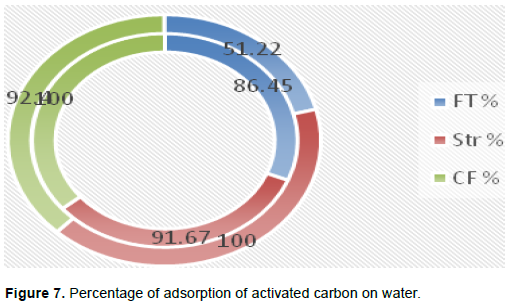

Water treatment and bacteriological analysis of sampled water

The treatment of the water sampled on activated charcoal made it possible to highlight a bacteriological analysis of this water before and after filtration, in order to count the quantity of total flora, total streptococci and coliforms, and faeces present in these waters and to see their evolution. Table 1 shows their presence and their evolution before and after filtration.

Taken under normal conditions of temperature and pressure (CNTP) (P = 1 bar and T = 25°C), the analysis shows that the well water contained 2.14×105 CFU/ml of total flora as long as Mangrove water contained a total flora of 3.28×105 CFU/ml. The culture media were prepared by agar on haggard (iced sugar) to identify and count streptococci and faecal coliforms. The total load of streptococcus in well water was, therefore, 1.2×104 CFU/ml and that of mangrove was 1×103 CFU/ml and the faecal coliforms thereof were 1.3×104 CFU/ml. For well water, faecal coliforms were not counted because of their abundance in this water. Total coliforms also could not be counted for the two types of water sampled. Otherwise, the analysis of the water after treatment with activated charcoal based on coconut pods, with a particle size of 20 µm and a specific surface of 658 m2/g (Table 1) revealed that the treated well water contained a total flora of 2.9×104 CFU/ml and that mangrove water contained 1.6×105 CFU/ml. In the gels, the streptococci contained in the treated well water had a load of 1×103 CFU/ml, the total coliforms of 1.16×105 CFU/ml and the faecal coliforms were completely absent. However, in the treated mangrove water the count showed that streptococci were rather absent, that there were 2.4×104 CFU/ml of total coliforms and 1×103 CFU/ml of faecal coliforms.

In the two samples analysed, it was noted in Table 1, a significant or even an uncountable quantity of certain bacteria. This was the case of total coliforms which, exceeding millions of CFU/ml, are considered dangerous in consumption. It is the cause of many diseases such as cholera, ringworm, scabies, and many others (Akoachere et al., 2013). Likewise, there was a strong presence of faecal coliforms in well water, but a total flora which was not abundant. We can deduce that this was due to the fact that the well is a closed vase which does not flow its water naturally like the mangrove, or might even have come from an unhygienic behaviour of the users or from the use of non-clean equipment (buckets, ropes, covers, coping, lack of personal hygiene), or other exogenous contamination which would encourage their multiplication (Benajiba et al., 2013). However, the mangrove with few faecal coliforms has circulating water that is not stagnant. Thanks to its trees, it manufactures organic matter for the food of certain species such as fish. The streptococci in this water are also scarce because they are digested by these species. In well water, on the other hand, there are a large number (1.2×104 CFU/ml for well water and 1×103 CFU/ml for mangrove water). Their contamination is very harmful for the organism.

There is a link between faecal coliforms and streptococci. Indeed, the two groups of germs are hosts of the digestive tract, with the difference that the faecal coliforms testify to a recent faecal contamination while the faecal streptococci, more resistant in the environment, testify to an old faecal contamination (Trevisan et al., 2002). Their presence in water marks faecal contamination from household waste water, toilets built near used water sources, individual deposits, and/or soil contamination (Gondim et al., 2016; Sepehrnia et al., 2017).

However, activated carbon filtration based on coconut pods, with pore sizes of 20 µm and specific surface of 658 m2/g of the different sampled waters showed after analysis a significant reduction or even absence of certain groups of bacteria such as streptococci and faecal coliforms. This issue proves the effectiveness of activated carbon in water treatment and the importance of introducing it into a water treatment circuit for any production; but also in improving the living conditions of the populations of BONAPRISO where access to the potable water is difficult. Figure 7 demonstrates this. The adsorption percentages recorded showed the sensitivity of coliforms, streptococci, and total flora to activated carbon. Activated carbon had adsorbed 86.45% of total flora; 91, 67% streptococci and 100% faecal coliforms for well water. Likewise, in water in mangroves, activated carbon fixed 100% streptococci, 92.4% faecal coliforms and 48.78% total flora. Such a case is considerable because, fixed at more than 50%; the efficiency of the activated carbon must be improved either by increasing the specific surface and the size of the pores, or by meeting the conditions for taking samples as much as possible to reach 100%. This activated carbon, therefore, acted on average in well water at 92.70%, a satisfactory percentage for the study; and in mangrove water at 81.20%. The work of Bryant and Tetteh (2015) also shows that after filtration of its waters the activated charcoal adsorbed the bacteria to more than 85%. Activated carbon fixed 100% streptococci, 92.4% faecal coliforms and 48.78% total flora.

To properly conduct the studies by filtering water at 100% adsorption with activated carbon, these precautions were taken beforehand:

(1) Taking samples was under maximum conditions after reading the instructions carefully before taking samples;

(2) The installation of a city equipment in liquid sanitation system;

(3) The ban on uncontrolled discharges of domestic and industrial wastewater was respected;

(4) Regular monitoring and chlorination of groundwater was carried out as it could significantly reduce the degree of bacteriological contamination of the water studied;

(5) The provincial protocol in the event of a flood was followed;

(6) The well that did not comply with current standards was upgraded;

(7) Invested in a treatment system.

It, therefore, appeared that the activated carbon adsorbed 86.45% of total flora for 13.55% of remaining flora, 91.67% of streptococci for 8.33% remaining, and 100% of faecal coliforms for the water of well; and that it fixed 100% of streptococci, 92.4% of faecal coliforms, therefore leaving 7.6% of total flora, and 48.78% for mangrove water. These results show the effectiveness of coconut powder on the treatment or filtration of water for domestic needs.