ABSTRACT

This study examined the adsorption of copper onto raw Globimetula oreophila leaves. The adsorbent surface nature was examined using scanning electron microscopy and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Adsorption parameters such as the –log10[H+], point of zero charge, initial metal concentration, mass of biomass and contact time were determined. Copper adsorption decreased gradually with pH. The point of zero charge (PZC) obtained was 4.5. The percentage adsorption capacity increased from 97.6 to 99.3% as the initial amount of copper rose from 20 to 100 mg/L. Temkin isotherm gave the best fit (R2=0.99) in describing the adsorption equilibrium process. Contact time effect resulted in an equilibrium attained in 15 min due to the initial rapid increase in adsorption. Kinetic data were excellently fitted to the pseudo-second order model. Thermodynamic studies affirmed a spontaneous and endothermic adsorption process. The activation energy and the energy of adsorption obtained affirmed that the adsorption process was chemisorption. G. oreophila is a recommendable adsorbent for the remediation of copper contaminated soil.

Key words: Globimetula oreophila, kinetics, adsorption, isotherm, copper.

Toxic metals availability in the environment are major problem to the world because of its adverse effect on human race. These metals even in trace amount are very harmful to man and his environment. They are persistent in the environment and cannot be degenerated or destroyed. They are found to aggregate in the soil, sediment, seawater and freshwater (Chowdhury and Saha, 2012). The effluents containing heavy metals are discharged into water bodies. Culpable industries are paints and pigments, refineries, metal cleaning and plating baths, fertilizer, paper board mills, wood preservatives, printed circuit board production, pulp, wood pulp production (Chowdhury and Saha, 2012; Zhu et al., 2009, Alao et al., 2014).

Copper is one of the most harmful metals to man and animals if it exceeds the permissible levels. The copper levels in drinking water based on the study from Europe, Canada and USA range from ≤0.005 to ?30 mg/L, with the primary source most often being the corrosion of interior copper plumbing (US EPA, 1991; Health Canada, 1992; IPCS, 1998; US NRC, 2000; WHO, 2004). The effluents from industries mostly have high amount of copper (II) ion (Tong et al., 2011). Human ingestion of excess copper ions may lead to possible necrotic changes in the liver and kidney, gastrointestinal irritation, central nervous problems, hepatic and renal damage, mucosal irritation, severe liver and brain damages, widespread capillary damages and depression (Ajaelu et al., 2017a; Ajmal et al., 1998; Larous et al., 2005).

Several methods available for reducing or totally removing the heavy metal from industrial wastewater include chemical precipitation, evaporation, ion exchange, reverse osmosis, filtration, solvent extraction, oxidation and electro deposition (Tong et al., 2011; Wang and Qin, 2005). The constraint associated with these procedures include the difficulty in removing low amount of heavy metals, inability to apply this method to considerable range of pollutants, it is not cost effective and mostly used for ex-situ amelioration (Ahmada et al., 2014). The use of activated carbon for adsorption is seen as effective but it is quite costly.

Globimetula oreophila is a member of the Loranthaceae family of parasitic mistletoes. Their leaves are greenish. 1000 species and about 75 genera are present in the Loranthaceae family. G. oreophila are found in the South West, South- South and South East of Nigeria. They are also found in the North West of Cameroon. All mistletoes species are members of the Loranthaceae family except those of North America and Europe. More than 60 species of the family have been located in West Africa. Some of the trees on which G. oreophila are found include cocoa tree, rubber tree and orange tree among others. It is acclaimed by the traditional health practitioners in Nigeria that the extracts of G. oreophila are employed in the prevention, treatment and management of cardiovascular related diseases and ailments (Faboro et al., 2018).

This study investigated the viability of G. oreophila for the adsorption of copper (II) ions from simulated waste water. Parameters studied included the effects of biomass, pH, point of zero charge and initial metal concentrations. Adsorption kinetics and effect of temperature were also studied.

G. oreophila leaves were harvested from Cocoa tree in Ondo State, Nigeria. The chemicals used include CuSO4.5H2O, HCl and NaOH. All these chemicals are of analytical grade.

Biomass preparation

The G. oreophila leaves were washed with distilled water and air dried after which they were oven-dried at 105°C overnight. Pulverization of the dried leaves was carried out followed by the screening through a 1 mm sieve to obtain the geometric size and then stored in an air tight plastic bag.

Adsorption studies

Biosorption procedures were carried out by varying the amounts of solution pH, initial Cu (II) ions concentration (having a pH of 4.57), mass of adsorbent, contact time and temperature under batch experiments. Adjustment of the solution pH was done by adding either 0.1 M NaOH or 0.1 M HCl solutions before adsorption experiment. The experiments took place on a Stuart Orbital Shaker at 250 rpm. The amount of Cu (II) ions was obtained using Atomic Absorption spectrophotometer (PG 990, PG instruments, Britain). The studies were performed in duplicate and the average value was used for later calculation.

Where q(mg/g) is the adsorption capacity, Co (mg/L) and Ce (mg/L) are the initial Cu2+ ion concentration and equilibrium Cu2+ ion concentration respectively, V(L) is the volume while W (g) is the mass of the adsorbent.

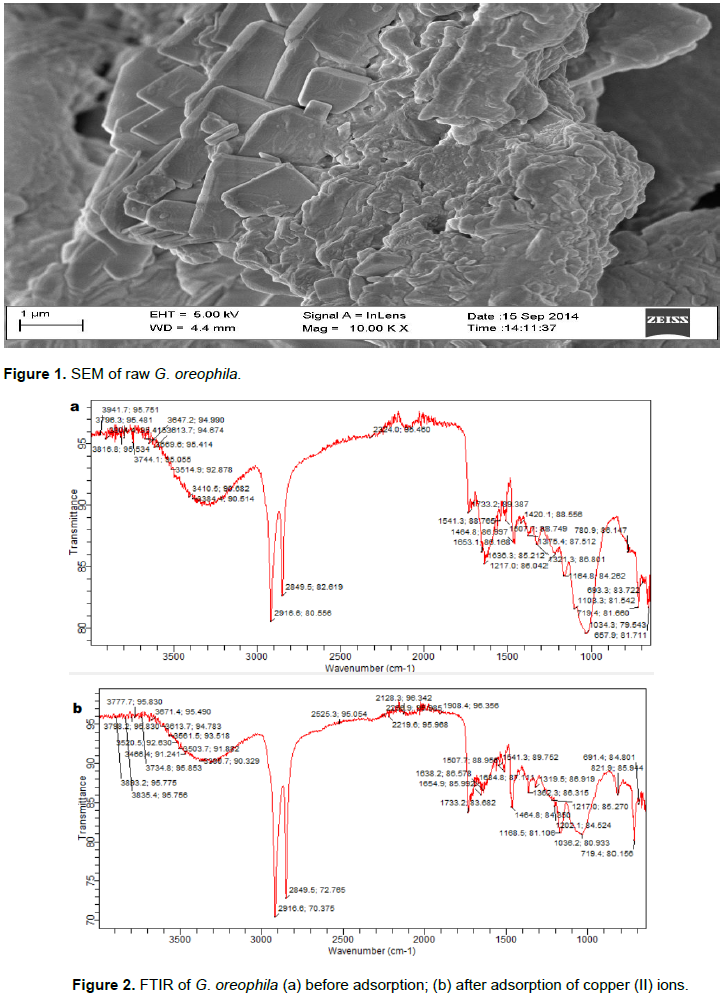

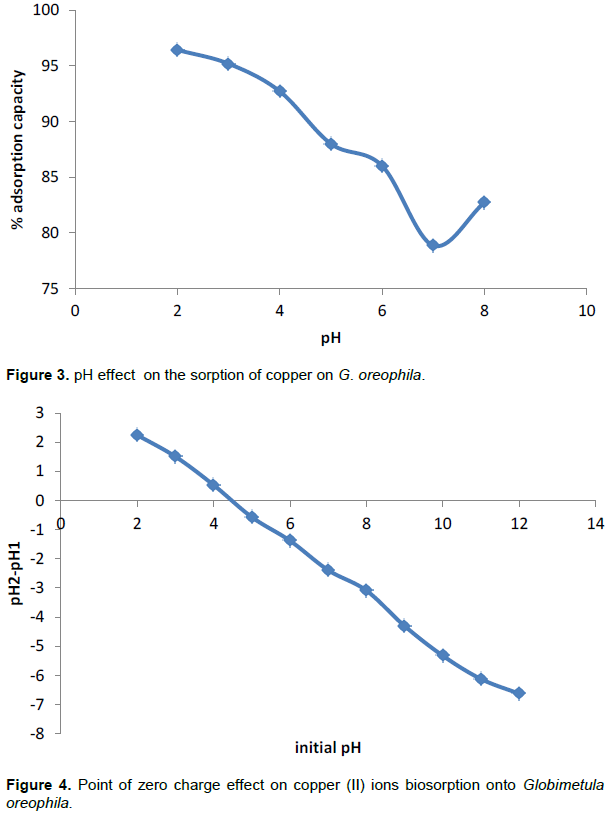

SEM and FTIR analysis

The surface structure was characterized by SEM as presented in Figure 1. The surface has irregular, flat sheets containing some pores. The irregular sheets are in layers. There may be the possibility of the adsorbent having a microporous and a mesoporous surface. Functional groups are possible adsorption sites for dyes. FTIR analyses of raw G. oreophila without and with copper as presented in Figure 2a and b reflect the following functional groups: Vibrational frequency appeared between 3514.9 and 3941.7 cm-1 attributed to the O-H stretching which shifted from 3520.5 to 3893.2 cm-1 for adsorbent with copper. The band at 3384.4-3514.9 cm-1 attributed to the N-H stretch shifted to 3230.7-3503.7 cm-1 in the G. oreophila with copper. The bands at 1636.3 - 1653.1 cm-1 corresponding to C=O of amide were shifted to 1638.2 - 1684.8 cm-1 for adsorbent with copper. The band at 1375.4 cm-1 for adsorbent without copper was shifted to 1319.5-1362.3 cm-1 for adsorbent with copper and is assigned to C-H rock of alkane. The band observed at 1164.8 - 1217.0 cm-1 for adsorbent without copper are attributed to -C-O stretch of alcohol was shifted to 1036.3 - 1217.0 cm-1 for adsorbent with copper. The band observed at 1164.8 - 1217.0 cm-1 for adsorbent without copper are attributed to -CN stretch aliphatic amine was shifted to 1036.3 - 1217.0 cm-1 for adsorbent with copper. These results show that the major functional groups responsible for the adsorption process are amide, amine and alcohol.

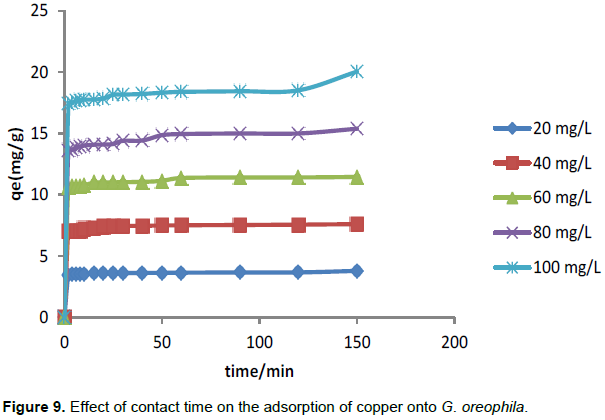

Effect of pH

The pH of solution has played a major role in the adsorption of heavy metals from aqueous solution and consequently waste water. The effect of pH was considered in the range 2.0 to 8.0 as seen in Figure 3. The pH at which the net surface charge on an adsorbent is zero is referred to as the point of zero charge, PZC. When the pH value is lower than PZC the number of negatively charged sites on the adsorbent reduces which results in the increase in the number of positively charged sites which enhances the adsorption of anions. At pH values greater than PZC, there is increase in the number of negatively charged sites on the surface of the adsorbent such that the extent of adsorption of cations increases because of ionic attraction between the negatively charged surface and the cationic adsorbate. The result obtained is quite surprising. Percentage adsorption increases with decrease in pH. The PZC obtained for Globimetula oroephila is 4.5 as shown in Figure 4. Below that value, the surface of the adsorbent is expected to be positively charged and the adsorbate is also positively charged. Possible explanation is that there may be some negatively charged functional groups responsible for the attraction and increase.

Initial copper concentration

Initial metal concentration has significant effect on the adsorption of metals by adsorbents. Figure 5 shows that percentage adsorption capacity increased from 97.6 to 99.3% as the initial metal concentration increased from 20 to 100 mg/L. This can result from the fact that at higher initial copper concentrations more vacant sites are available for adsorption. The variant concentrations enable the essential driving force to overwhelm the mass transfer of copper (II) ions between the solid and aqueous phases.

Effect of mass of biomass

Adsorbent mass is known to affect the capacity of adsorption of various adsorbents. Figure 6 reports the adsorptive removal of Cu(II) ions by G. oreophila. Adsorption capacity of G. oreophila reduces with a rise in the mass of biomass. The reduction in the amount of copper adsorbed at the surface of G. oreophila with increase in mass of biomass can be ascribed to the concentration gradient or split in the flux between the amount of copper in the solution and that on the surface. Therefore, the amount of copper adsorbed onto unit mass of adsorbent (G. oreophila) reduces as the adsorbent weight rises, thus leading to a reduction in the amount of Cu(II) ions adsorbed (qe) as the weight of adsorbent rises. Similar findings had been described by Ajaelu et al. (2017a) and Zafar et al. (2006).

Adsorption isotherms

Equilibrium adsorption isotherms are vital in designing adsorption process for they strongly imply metal ions distribution between the phases that are liquid and the adsorbent at equilibrium with respect to the metal concentration. Each time an adsorbent contacts a solution of metal ion, the surface of the adsorbent experiences a sudden rise in the concentration of metal ions until a dynamic equilibrium is attained. Four biosorption models specifically, Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin and Dubini-Radushkevich were employed to describe the adsorption of copper on G. oreophila. The Langmuir model surmises that adsorption sites are equivalent and adsorption at each site is not dependent on adsorption or desorption at adjacent sites. The linear expression of the Langmuir equation is as follows:

Where Ce and qe are the amount of solute in the solution at equilibrium ((mg/L) and the amount of solute adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent (mg/g), respectively. Qo (mg/g) refers to the highest level of monolayer uptake capacity and b (L/mg) is a constant associated with the free energy of adsorption. Figure 7a presents the graph of Ce/qe and the amount at equilibrium (Ce). The slope and intercept from the plot were used to calculate the values of Qo and b as presented in Table 1. A dimensionless equilibrium factor, RL that describes the favourability of adsorption was obtained from the expression (Weber and Chakkravort, 1974).

The magnitude of E explains the ion-exchange, physical or chemical sorption of the adsorption process. As reported by Atkins and Paula (2006), physisorption, can be caused by weak van der Waal interactions between the adsorbent and the adsorbate. The energy of physisorption is in the region of less than 20 kJ/mol.

Atkins added that there is covalent bond between the adsorbate and the adsorbent in chemisorption in which the substrate (adsorbent) is limited to monolayer coverage. The value of E, the mean free energy of biosorption, determined from this study as reported in Table 1 was higher than 20 kJ/mol, thus chemisorption process predominates. Out of the four adsorption isotherms, Temkin isotherm gave the best fit.

Copper adsorption kinetics

Contact time effect

Figure 9 reports the contact time effect on the sorption of copper by G. oreophila. Adsorption increases rapidly initially and reached equilibrium in 15 min of mixing of G. oreophila with the copper solution. This occurred due to the numerous available active sites on the adsorbent surface and the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged copper (II) ions and the negatively charged surface of G. oreophila. As copper (II) ions occupy the sites, electrostatic repulsion gradually increases between the copper (II) ions present in the site and the copper (II) ions present in the solution. This consequently reduces the adsorption of copper (II) ions and thus equilibrium is established.

Kinetic effect on the process of adsorption is vital since it explains the rate of adsorption of the adsorbate which then regulates the contact time of the G. oreophila at the solid–solution interface. The kinetics of copper biosorption by G. oreophila was analyzed using the Pseudo- first and pseudo-second order models. The Langergren pseudo-first order expression is given below:

Where qexp is the amount of copper (II) ions obtained by experiment and qcal values are the amount of copper (II) ions obtained by calculation, and p is the number of determinations. The low value of ?q corroborates the study that the pseudo-second order kinetic isotherm is better explaining the adsorption kinetics of copper onto G. oreophila. Previous study on the adsorbent, Tectona grandis, reported similar result (Ajaelu et al., 2017b).

Thermodynamic effect

The temperature effects were investigated at 303, 308, 313 and 318 K. Figure 11 shows that there was a slight reduction in the adsorption capacity as the temperature decreases. This means that the adsorption process was chemisorptions, corroborating the earlier mentioned mean free energy of biosorption obtained from Dubinin-Radushkevich model. The thermodynamic parameters determined were calculated as follows:

The entropy change ΔS as well as the enthalpy change ΔH was calculated from the plot of lnK against 1/T as presented in Figure 12. The KL values were calculated from the expression K = qe/Ce at different amounts of Cu (II) ions from 20 to 100 mg/L, and the data are reported in Table 3. The adsorption of copper on G. oreophila is spontaneous (ΔG is negative) and endothermic (ΔH is positive). Moreover, there is a rise in entropy (ΔS is positive) at the adsorbent-adsorbate interface and this positive value means that the adsorbate species displace the adsorbed solvent molecules to gain more translational entropy than was lost by the adsorbate, thus allowing randomness in the system (Baccar et al., 2013).

The adsorption activation energy was determined using the Arrhenius equation for it denotes the minimum energy required for the adsorption reaction to proceed. The equation is given by:

The value of Ea (168.3 kJmol-1) falls in the energy range of 40 to 800 kJ/mol, which means that chemisorption is the process of adsorption.

Ionic strength effect

Ionic strength has significant effect on the adsorption process. Figure 13 presents the influence of ionic strength on the adsorption capacity of copper unto G. oreophila. As the ionic strength increases from 0.02 to 0.08 moldm-3, the capacity of adsorption increased from 231 to 1620 mg/g. This shows that adsorption increases with increase in ionic strength. This result is contrary to what was obtained by some researchers. These may be due to accessibility modification of the functional group sites that binds metals on the G. oreophila surface as well as the modification in the activity of the aqueous metal cations as a function of ionic strength (Borrok and Fein, 2005).

This study investigated the adsorption efficiency of raw G. oreophila on copper. Increase in initial copper concentration increases the adsorption capacity. Equilibrium isotherm shows that of the four isotherms, Temkin model is the most appropriate for explaining the adsorption process. D-R isotherm, as well as the activation energy, which is the minimum energy required for the adsorbent- adsorbate interaction, shows that the adsorption process is chemisorption. Increase in ionic strength significantly increased the capacity of G. oreophila in removing copper from solution. This study reports the usefulness of G. oreophila as an adsorbent for removing copper from aqueous solution.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

The author appreciates Miss Bukola Adegeye and Dr. S. A. Ayanda for their assistance rendered in this study.

REFERENCES

Ahmada MA, Ahmada N, Bello OS (2014). Removal of Remazol Brilliant Blue Reactive Dye from Aqueous Solutions Using Watermelon Rinds as Adsorbent. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 36:845-858.

Crossref |

|

|

|

Ajaelu CJ, Dawodu MO, Faboro EO, Ayand OS (2017a). Copper Biosorption by Untreated and Citric Acid Modified Senna alata Leaf Biomass in a Batch System: Kinetics, Equilibrium and Thermodynamics Studies. Physical Chemistry 7:31-41. |

|

|

Ajaelu CJ, Ibironke L, Oladinni AB (2017b). Copper (II) ions adsorption by Untreated and Chemically Modified Tectona grandis (Teak bark): Kinetics, Equilibrium and thermodynamic Studies. African Journal of Biotechnology 18(14):296-306.

Crossref |

|

|

Ajmal M, Khan AH, Ahmad S, Ahmad A (1998). Role of sawdust in the removal of copper (II) from industrial wastes. Water Research 32(10):3085-3091.

Crossref |

|

|

|

Alao O, Ajaelu CJ, Ayeni O (2014). Kinetics, Equilibrium and Thermodynamic Studies of the Adsorption of Zinc (II) ions on Carica papaya root powder. Research Journal of Chemical Sciences 4(11):32-38. |

|

|

|

Atkins P, Paula J (2006) The extent of adsorption. Atkin's Physical Chemistry. 8th Ed.:916-918. |

|

|

Baccar R, Blánquez P, Bouzid J, Feki M, Attiya H, Sarrà (2013). Modeling of adsorption isotherms and kinetics of a tannery dye onto an activated carbon prepared from an agricultural by-product. Fuel Processing Technology 106:408-415.

Crossref |

|

|

Borrok DM, Fein JB (2005). The impact of ionic strength on the adsorption of protons, Pb, Cd and Sr onto the surface of Gram negative bacteria: testing non-electrostatic, diffuse and triple-layer models. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 286(1):10-126.

Crossref |

|

|

Chowdhury S, Saha PD (2012). Batch and continuous (fixed bed column) biosorption of Cu (II) by Tamarindus indica fruit shell, Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 30:369-378.

Crossref |

|

|

Faboro EO, Olawuni IJ, Akinpelu BA, Oyedapo OO, Iwalewa EO, Obafemi CA (2018). In Vitro Evaluation of Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Properties of Methanol and Dichloromethane Extracts of the Leaf of Globimetula oreophila. Chemical Science International Journal 23:1-15.

Crossref |

|

|

|

Health Canada (1992). Copper. In: Guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality. Supporting documentation. Ottawa, Ontario. |

|

|

|

International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) (1998). Copper. Geneva, World Health Organization, International Programme on Chemical Safety (Environmental Health Criteria 200). |

|

|

Larous S, Meniai AH, Lehocine MB (2005). Experimental study of the removal of copper from aqueous solutions by adsorption using sawdust, Desalination 185(1-3):483-490.

Crossref |

|

|

|

Temkin MI (1941). Adsorption equilibrium and the kinetics of processes on nonhomogeneous surfaces and in the interaction between adsorbed molecules. Zh. Fiz. Chim 15:296-332. |

|

|

Tong TS, Kassim MJ, Azraa A (2011). Adsorption of copper ion from its aqueous solution by a novel biosorbent. Uncaria gambir: Equilibrium, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies. Chemical Engineering Journal 170:145-153.

Crossref |

|

|

|

US EPA (1991). Maximum contaminant level goals and national primary drinking water regulations for lead and copper; final rule. US Environmental Protection Agency. Federal Register 56(110):26460-26564. |

|

|

|

US NRC (2000). Copper in drinking water. Washington, DC, National Research Council, National Academy Press. |

|

|

Wang XS, Qin Y (2005). Equilibrium Sorption Isotherms for Cu2+ on Rice Bran. Process Biochemistry 40:677-680.

Crossref |

|

|

Weber TW, Chakkravort RK (1974). Pore and solid diffusion models for fixed bed adsorbers. American Institute of Chemical Engineering Journal 20:228.

Crossref |

|

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO) (2004). Copper in water. Background document for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality WHO/SDE/WSH/03.04/88.

View

|

|

|

Zafar MN, Nadeem R, Hanif MA (2006). Biosorption of nickel from protonated rice bran. Journal of Harzadous Material 143:478-485.

Crossref |

|

|

Zhu SZ, Wang LP, Chen W (2009). Removal of Cu (II) from aqueous solution by agricultural by product: peanut hull, Journal of. Hazardous Materials 168:739-746.

Crossref |