Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This study evaluated the criticality of change leadership to business survival in a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) environment, focusing on Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (ZSE)-listed companies in the COVID-19-affected trading period of March to December 2020. As 21st-century VUCA environments are putting business survival under growing pressure, the study sought to verify how much change leadership could mitigate VUCA’s adverse impacts on viability. SPSS v.20 bivariate analysis was used to test the study’s alternative hypothesis and establish a correlation between the change leadership aspects of vision, understanding, clarity, and agility and business survival in a VUCA environment. Theoretical and empirical literature noted broad consensus on leadership’s importance for organizational change initiative success, especially in turbulent environments. A mixed-methods approach was used as the study was qualitative and quantitative. The study found that change leadership practice was common in ZSE companies during the studied COVID-19 period and most change and change leadership interventions were very feasible. It also found that the interventions were largely inevitable and significantly effective and that change leadership is crucial to business survival in a VUCA environment. Further, other factors besides change leadership were found significant for ZSE firms’ survival in the era. It was suggested that corporate sector resilience initiatives be established in order to empower local businesses to survive growing VUCA pressures, which could help to boost potential local and foreign corporate investor confidence. Further, creating inclusive business change leadership educational awareness forums and/or institutions can help to capacitate local businesses to survive inevitable future VUCA episodes.

Key words: Change leadership, change, business survival, viability, VUCA, COVID-19.

INTRODUCTION

Globalization’s dynamism and complexity are increasingly pressing organizations to adapt for survival and sustained relevance (Issah, 2018). 21st-century leaders thus bear the onus to successfully lead change in their entities (ibid), despite reports of 50-70% planned change failure rates (Dinwoodie et al., 2015; McKinsey and Company, 2019). These reports suggest the ineffectiveness of change implementation approaches and have been repeatedly contested for lack of valid and reliable empirical evidence (Hughes, 2011; Wilkinson, 2020). There is a broad consensus that leadership is indispensable to business survival in times of upheaval (Cabeza-Erikson et al., 2008; Hao and Rashad, 2015; Heathfield, 2020) such as the present COVID-19 era. Despite this, it has been argued that most firms still undervalue and misunderstand change leadership (Kotter, 2011; Dinwoodie et al., 2015).

Zimbabwean companies, including those listed on the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (ZSE), were not spared by the novel COVID-19 environment’s negative impacts and were invariably forced to adapt for survival. This study thus sought to understand the change and change leadership approaches adopted by ZSE firms to counter the pandemic’s volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) and to establish their effectiveness and criticality for survival in the choppy era. Study outcomes were intended to avail more empirical evidence and help further clarify change leadership’s role in and value to business survival in VUCA environments. This would ultimately aid a stronger, evidence-based case for the wider adoption of change leadership towards a more resilient corporate sector locally and, possibly, beyond.

THEORETICAL REVIEW

Change is an inevitable feature of organizational life (Cummings and Worley, 2009) and is synonymous with standard practice as organizations are deemed living entities that must constantly change to remain viable (Makumbe, 2016). It has also been argued that organizational leadership and change are closely linked and neither can successfully occur without the other (Burnes et al., 2016). However, most organizations largely manage change and exhibit little change leadership (Kotter, 2011; Dinwoodie et al., 2015; El-Dirani et al., 2020). Further, despite change management being over 50 years old, it has been widely reported that 50 – 70% of change efforts fail (Dinwoodie et al., 2015, McKinsey and Company, 2019), suggesting flaws in many change management efforts. These high change failure claims have, however, been repeatedly challenged for lack of valid and reliable empirical evidence (Hughes, 2011; Wilkinson, 2020).

It has been argued that successful change needs both change management and change leadership (Dinwoodie et al., 2015). Change leadership means being able to influence and inspire others into action and respond with vision and agility when there is growth, disruption or uncertainty to cause necessary change (Akpoveta, 2020). Organizations seem divided on change leadership’s value, despite leadership being deemed as key to successful change (American Management Association, 1994). This particularly applies to change needed to survive in VUCA operating environments such as that of the current COVID-19 era. However, the narrative that successful change hinges on effective leadership has been challenged as a mere assumption with little empirical proof (Ford and Ford, 2012; Burke, 2008).

Against this mixed background, today’s business environments reflect escalating VUCA that demands firms to be more agile or adaptive to sustain viability (Phillips, 2019; Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri, 2017). This implies that change is inevitable to survive the current era’s relentless upheavals. Survival in VUCA climates needs leaders to apply a strategic tool called VUCA PRIME (Johansen, 2007) which transforms VUCA into the positive outcomes of vision, understanding, clarity, and agility. It partly leverages the LIVED® (A & DC, 2014) VUCA change leadership model wherein leaders aptly apply learning, intellect, values, emotions, and drive. Transformational leadership (Burns, 1978) and Kotter (2011)’s change leadership models are also essential for ensuring survival in VUCA climates.

The present COVID-19 era’s VUCA impacts affected and continue to affect local businesses, including ZSE-listed companies. A survey across 210 multi-sectoral private sector businesses noted significant revenue losses, supply chain and labor supply disruptions, and decision-making uncertainty (ZNCC, 2020). Local businesses were thus invariably driven to implement change in varied formats to survive. Against this setting, this study thus sought to investigate how significant change leadership efforts in ZSE-listed companies were and/or have been towards ensuring business survival in the difficult pandemic era.

Business survival in VUCA environments

Business survival is the operation of a business entity on a going-concern basis (Akindele et al., 2012). Alternatively, it is simply managing to remain active in business. Within this study’s context, business survival can be defined as the ability of a business entity to remain operational and maintain viability within a VUCA operating environment. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO, 2020) defines business viability as its ability to survive linked to its financial performance and position. The ATO further notes that a viable business earns enough profit to give a return to its owner and meet its obligations to creditors as well as retaining enough cash to sustain itself through a period/s of non-profitability. As noted above, a VUCA operating environment typically challenges any business entity by affecting its internal and external environments which then usually impacts its viability. Internal environment factors include resistance to change (El-Dirani et al., 2020), internal control lapses, poor financial management, and high staff turnover. The external ones include government regulation, economic recession, political turmoil, intense price competition, customer behavioral changes, health issues, technological changes, natural disasters, and supply chain disruptions (Obasan, 2014). These challenges usually necessitate constant change to ensure the entity’s ability to survive or remain viable. Consequently, businesses must prioritize keeping track of various environmental changes to assure survival in the long run. Thomas (2003) notes that in the modern uncertain economic climate, the small entrepreneur’s priority is to ensure survival. It can, however, be argued that even big organizations may be drawn to prioritize survival by peculiar VUCA circumstances - the current COVID-19 global pandemic being a case in point.

Sarkar (2016) argues that critical factors for a business’ survival and success in a VUCA world include well-crafted operational basics, innovativeness, quick responsiveness, adaptability, and effective broad change and diversity management. She further cites the need for efficient market intelligence and extensive multi-stakeholder collaboration as also crucial for the same purposes. Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri (2017) assert that for a business to win in a VUCA environment it must first address hardware aspects - basically implying having systems, processes, structures, and other mechanistic control frameworks. Part of this hardware is strategic foresight and agility, which entails a keen ability to efficiently manage both the immediate and future business goals. Volatile and turbulent times require a business to be firmly anchored on its vision whilst concurrently managing short-range targets (ibid).

Business survival in VUCA times also demands a consumer-centric operational philosophy (ibid).This is important because consumers’ tastes and preferences tend to change rapidly in volatile environments, as previously highlighted. Further, the 2 authors state that enduring survival in VUCA times requires a business to “think local and act global.” This means remaining relevant to and meeting the local market needs through exploiting globally-influenced resources such as knowledge and technology to deliver suitable solutions. Also, long-term business survival and success banks primarily on the ability to attract, groom, and retain great intellectual talent (ibid). Through being groomed and developed to believe in the business’ vision and mission such talent can be effectively harnessed to consistently turn in superb performances for the firm.

Finally, the ever-evolving and volatile external environment in which most business firms exercise rivalry invariably means that the operating environment has a significant influence on business survival prospects (Alexander and Britton, 2000). Consequently, business entities should diligently assess the impacts and potential impacts of their operating environments through regular, deliberate, and thorough environmental scanning. A commonly used tool in this process is PESTLE analysis which examines the political, economic, social, technological, legal, and (physical) environmental/ ecosystem aspects of the operating environment. In a VUCA environment, however, the practical utility of such rigorous analysis may be lost due to high volatility which may rapidly invalidate valuable analyses before they can be put to any good use.

Business leadership in VUCA environments

Twenty first century organizations operate in ever-more VUCA environments (Mack et al., 2015) which often pose challenges that can threaten the very survival of business firms. By definition, VUCA implies change in the ope-rating environment and change that is more often than not trying and demanding shrewd responses. VUCA is also often a paradoxical phenomenon in that whilst it can trigger or promote innovation, development, and progress it can also equally hinder or stall the same in its stride. The dynamic and difficult nature of all 4 aspects of VUCA thus typically presents tough leadership tests for the global business community at large. Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri (2017) state that, starting from the highest executive level, leaders have a central role in ensuring their firms’ responsiveness to a VUCA business environment’s demands.

To effectively address VUCA challenges, Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri (2017) argue that business leaders must create an open environment promoting dis-covery, diverse views, and experimentation. They further assert that the leaders must capably identify opportunities invoked by emergent technologies and excel in translating new information into capability differentiation. The two authors also note that leaders must identify their firms’ knowledge and skill gaps inherent in their business practices, processes, and systems. Above all, leaders must promote broad decision-making based on critical thinking by focusing on the thought process rather than thought content. Critical thinking demands conscious and skillful conceptualization, analysis, forming, and/or evaluation of information from communication, observation, experience, reflection, or reasoning to guide decisions and action. It is thus arguably a hallmark of effective change leadership, especially in VUCA times.

It is pertinent to note that VUCA existed even long before the term was coined in the 1990s. Two epic examples are the global Great Depression episode of 1929 -1939 and the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918–19. However, today’s cocktail of rapid geopolitical, economic, socio-cultural, and technological changes have escalated its frequency and intensity (Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri, 2017). Makumbe (2016) cites typical VUCA business challenges in the constantly changing global consumer tastes and preferences, adaptation to rapid and broad technological change, workforce diversity management, and tackling ruthless global competition.

Brutal (Red Ocean) competition suggests that some businesses may not survive in the battle for markets and sustained relevance unless their leaders stand up to the task. Joy (2017) cites the former Finnish cellular phone giant, Nokia Corporation, who led the global cell phone market in the first decade of the 21st century but then succumbed to more agile and shrewd competition from Apple Inc. and Samsung Corporation. Market volatility accounted for Nokia’s demise as the electric pace of change in customer preferences meant the firm should not have rested on its laurels of market leadership as astute rivals were busy in the shadows. Consequently, having foreseen smart phones as the future of mobile telephony and convenience, Apple and Samsung leaders swiftly leveraged the market’s fluidity in brand loyalty to launch their game-changing mobile devices. Thus began the demise of the once-mighty Nokia Corporation.

As cited by Sarkar (2016) in the previous section, 3 of the factors critical for success in VUCA environments are rapid response (agility), innovation, and flexibility (adaptability). From the foregoing example, Nokia failed in these respects, thus ceding its competitive edge to shrewder rivals. Notably, all 3 factors are leadership hallmarks, thereby implying that business leaders have a central role to play in facilitating the viability of their organizations when operating in such environments. Business survival in VUCA climates requires a firm’s leadership to develop the capacity for translating “undesirable VUCA” into “useful VUCA” strategic responses. These essentially antidotal responses derive from a strategic leadership tool called VUCA PRIME which entails leaders turning volatility into vision, uncertainty into understanding, complexity into clarity, and ambiguity into agility (Johansen, 2007).

VUCA PRIME posits that volatility should be countered by a clear sense of vision. During rapid change, people need direction, though with possible adjustment in route (Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri, 2017). Clear vision aids focus on vital actions and prioritizing in the face of emergent tasks, demands, and opportunities. Further, uncertainty can be cleared through seeking understanding. In this regard, detailed communication (People Management Insight, 2017) is key for everyone to have the same understanding of issues and also for leaders to connect with their peoples’ thoughts and emotions (Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri, 2017). Complexity can be overcome through being clear about what can be known and what cannot and consciously acting more to simplify and control the former whilst monitoring the latter (Johansen, 2007) to a reasonable extent. Finally, the antidote to ambiguity is agility, meaning where there is potential for misinterpreting environmental signals people must be flexible enough to react to whatever outcome.

The process of leveraging VUCA PRIME is neither simple nor confined to straight rules. Consequently, Sarkar (2016) points out that another critical leadership enabler for navigating VUCA settings is an extensive multi-stakeholder collaboration with workers, customers, shareholders, and society amongst others. This resonates with Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri (2017) who state that in VUCA greater focus must be on collective rather than individual leadership. This inclusive leadership approach demands both humility and responsibility. Business leaders thus have a key role in exercising responsible leadership in the quest to ensure that their organizations can survive and thrive in VUCA environments (Sarkar, 2016). In principle, responsible leadership blends the core qualities of the trans-formational, servant, and authentic leadership styles to focus on broad, multi-stakeholder interactive relationships – making for a more holistic approach to solutions for a firm’s challenges (Sarkar, 2016).

In line with Sarkar (2016)’s thinking, Kok and Van den Heuvel (2019) assert that modern leaders need strong discernment to enable them to control their thinking when acquiring and applying knowledge towards making right, equitable, and just decisions. They further state that for leaders to excel in discernment in VUCA times, they must consistently collaborate with heterogeneous teams in making decisions. As Phillips (2019) argues unless leaders become more adaptable in addressing unrelenting VUCA environment changes through humbly tapping into the ready-resource of change stakeholders, their future certainly looks doomed and they and their firms may not survive. Indeed, leaders alone may not always have the answers to their businesses’ VUCA challenges that threaten survival and sustained relevance.

Conceptual framework

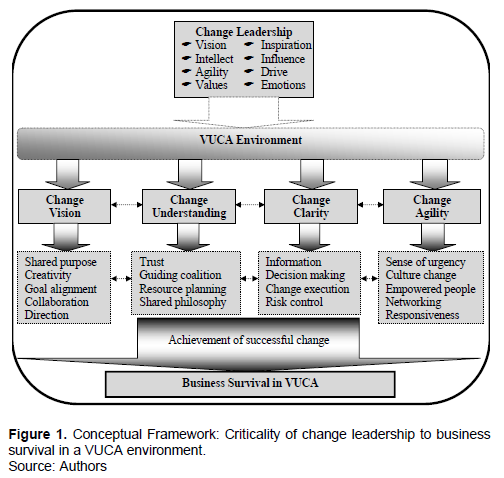

A conceptual framework derives from the theoretical framework and thus uses past study outcomes to propose a “base” theory for the current research (Maigher, 2018). It identifies the study’s independent and dependent variables and shows the possible relationships between them.

Using Akpoveta’s change leadership definition, Johansen’s VUCA PRIME tool, Kotter’s 8-step change leadership model, Burns’ transformational leadership model, and the LIVED VUCA model, the researcher came up with a conceptual framework shown in Figure 1.

From the theoretical literature review, it was learnt that leaders of firms operating in the turbulent and dynamic environments of VUCA can effectively deal with its 4 undesirable elements through the adoption of Robert Johansen’s VUCA PRIME philosophy. This means that by applying their defining personal attributes of visionary mindset, intellectual prowess, inspiration, drive, influence, and so on, they will effectively establish the vision, understanding, clarity, and agility required for the change that is necessary for their organizations to survive and thrive.

Change vision is a clear picture of an organization’s future position after going through change (Kotter, 2012). Ideally, it must appeal to employees as being feasible and desirable if the change is to be embraced. Change understanding is the mutually-shared thinking and feelings about the purpose of change created through effective communication of the change vision (Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri, 2017). Change clarity is the distinction between what can and cannot be known and efficiently using the knowable to simplify operations whilst consciously striving to limit the potential undesirable impacts of the unknowable (Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri, 2017). Holsapple and Li (2008) define change agility as the compound effect of alertness to change and subsequent timely response to use or direct resources accordingly in a flexible and cost-conscious manner. These 4 change leadership ideals intricately interlink to facilitate a holistic and more effective approach to change leadership in VUCA times.

The establishment of the four change aspect targets, namely vision, understanding, clarity, and agility by a firm’s leaders provides a sound foundation for effective and efficient strategy formulation and implementation and operations through facilitating, amongst others, the following outcomes (Hejase, 2017):

1. shared purpose and philosophy throughout the organization,

2. individual creativity and team collaboration alignment of internal stakeholder goals towards firm goals,

3. efficient resource planning and allocation,

4. establishment of trust between leaders and followers,

5. information availability for risk control and decision making,

6. a sense of urgency and responsiveness throughout the organization,

7. people empowerment and effective networking, and

8. institutionalization of the required change in the organizational culture.

It is arguable that the extent to which the above (and other associated aspects) are realized through VUCA PRIME’s outcomes directly influences the prospects of a firm surviving and thriving in a VUCA environment. Hence, the more an organization excels in establishing the above-noted outcomes in its operations, the higher its prospects of survival and success in VUCA. In such a cli-mate, organizational survival depends more on inclusive, multi-stakeholder collaborative approaches than individual brilliance or unitary imposition (Sarkar, 2016).

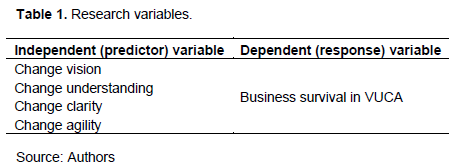

From the proposed conceptual framework (Figure 1), the following independent (predictor) and dependent (response) variables in Table 1 are determined for the study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research philosophy

The study adopted the pragmatic philosophy. Research philosophy is a system of beliefs and assumptions on how knowledge is developed in a certain field (Saunders et al., 2019). It defines the basic nature of the knowledge involved in a study and the process of how it is developed. Saunders et al. (2019) further state that in pragmatism both positivism and interpretivism can be simultaneously adopted for data collection, analysis, and interpretation. In this study, knowledge was thus developed using positivist and interpretivist processes. Further, pragmatic research is instigated by a problem and seeks to proffer feasible solutions to inform future practice (Saunders et al., 2019). This research was stirred by the pressure that the 21st-century VUCA environments are increasingly putting on businesses to survive and sought to verify the extent to which change leadership practice could provide a panacea to VUCA’s concomitant challenges.

The positivist dimension of pragmatic research focuses on exploring an observable reality towards drawing some conclusion of a generalized law-like nature (Saunders et al., 2019). Further, Hejase and Hejase (2013) contend that “positivism is when the researcher assumes the role of an objective analyst, is independent, and neither affects nor is affected by the subject of the research” (p.77).This research sought to evaluate the criticality of change leadership to the observable reality of business survival in a VUCA environment by testing a hypothesis to deduce some general theoretical link between the 2 variables. The hypothesis testing aspect gave the study a positivist dimension and was applicable since the literature review showed no existing specific theoretical relationship between the study variables. However, evidence from the same literature repeatedly suggested a possible connection between these same variables.

Pragmatism also stresses that knowledge is both constructed and based on personal experiences and subsequent individual interpretation (Robson and McCartan, 2016). Thus, it recognizes the reality of human experience and its inescapable influence on study outcomes. Therefore, the results of any research that studies people depend on individual interpretation of the study variables and are thus qualitative and subjective. This study’s variable of change leadership criticality bore this nature as it relied on the individual opinions of various company participants on the issue. Hence, this nature of the knowledge involved in the study necessitated a pragmatic process to appropriately develop the required knowledge.

Research approach

This study adopted the fixed mixed-methods approach since it had both qualitative and quantitative aspects as noted above. Creswell and Plano-Clark (2018) state that the fixed mixed-method approach involves a predetermined and pre-planned use of quantitative and qualitative methods from the beginning and the implementation of procedures as planned. Abductive reasoning was applied since a pragmatic philosophy was used. Abduction blends induction and deduction and this study was biased towards induction since there was no pre-existing theory to develop by rigorous testing (Saunders et al., 2019). Instead, the study involved developing a theoretical link between change leadership and business survival in a VUCA environment using previous knowledge and any new findings. Since theory formulation would follow study data generation, which defines induction (Saunders et al., 2019), this approach was thus applicable.

Deduction fitted in this study since two aspects of it - the search for an explanation for causal relationships between the study variables and the necessity of selecting a large enough sample to generalize conclusions (Saunders et al., 2019) - applied to the study. There was a need to explain a cause-and-effect link between change leadership practice and business continuity in a VUCA environment. Since the research also sought to derive a generalized conclusion around the cited cause-and-effect link, it was vital to draw a sample that represented the population as closely as possible. This sampling occurred within a limited study time and a stratified sampling frame.

Research design

The study adopted descriptive, explanatory, and exploratory research designs with a major inclination towards exploratory and explanatory designs. Saunders et al. (2019) state that descriptive research enables one to identify and explain variability in different phenomena. In this study, descriptive design enabled the researcher to identify and describe the differences in business viability status between various ZSE-listed companies based on the change leadership practice dynamics between them.

Exploratory studies seek to better understand the nature of a problem or phenomenon where a little or no study or empirical evidence might exist on it (Hejase and Hejase, 2013; Sekaran and Bougie, 2016). In this study, the literature review noted scant research on the impact of change leadership on the effectiveness of change efforts. In particular, no specific past study on the possible link between change leadership and business survival in VUCA had been done. Thus, it was critical to explore the various impacts of different change leadership practices on the survival prospects of a business operating in a VUCA environment towards establishing the relationship between the 2 variables.

Explanatory or analytical research involves the examination of variables to explain existent or possible inter-relationships between them, especially cause-and-effect relationships (Saunders et al., 2019).This study sought to examine and explain the nature of the relationship between change leadership practice and the survival of businesses operating in VUCA environments.

Research strategy

A case study was chosen as a suitable research strategy. Yin (2018) defines a case study as a fact-based research strategy involving the in-depth investigation of a specific contemporary phenomenon or issue within its real-life context. This strategy suited this study which intended to build an evidence-based case for the criticality of change leadership to the survival of business in a VUCA environment. Evidence was collected from ZSE-listed companies in the form of their change leadership practices within the COVID-19 VUCA environment, the data analyzed and a determination made on the contribution of the practices to the firms’ survival. Further, a case study fitted well in this research as the study sought to investigate the contemporary issue of business survival in a VUCA environment - which issue has been and is still topical and is increasingly affecting the global business community, including ZSE-listed companies.

Saunders et al. (2019) further state that case studies are most often used for explanatory and exploratory research. This study’s topic had no known precedent and the literature review had shown scant empirical research on the impact of change leadership on organizations. Desirably, the case study of ZSE-listed firms in a COVID-19 era enabled an in-depth exploration of real change leadership practices and dynamics in businesses in a VUCA setting – thus helping to assess change leadership’s practical significance for business survival in fluid and challenging climates. A case study can generate insights from an intensive, real-life contextual examination of a phenomenon or complex subject giving a base for rich, empirical descriptions (Saunders et al., 2019). This study gave factual insights on the agile creativity and innovation exhibited by ZSE firms around COVID-19 complexities – which strategies may help to inform future responses in the event of further such pandemic-induced VUCA episodes.

Though applicable and beneficial for the reasons noted above, the case study strategy however limited the extent to which the research outcomes can be generalized to the Zimbabwean and worse still, global business contexts. Sekaran and Bougie (2016) define generalizability as the applicability scope of the research findings from one organizational or study context to other settings. In this study, research findings from the case of ZSE-listed firms were thus of a limited applicability scope, especially given the limited sample size. Further, a case study of several ZSE-listed firms was a challenge with getting the desired cooperation from some of the targeted respondents. This led to compromised choices of respondents to get a sufficient critical mass of participants, which inadvertently affected the targeted balance of managerial opinions.

Data collection procedures and techniques

Study population

The study population was the 55 companies actively listed on Zimbabwe’s main industrial equity trading market, the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange. This population consists of 10 industrial sectors - namely agriculture and agro-processing; banking, finance, and insurance; consumer and specialty retail; diversified manufacturing and services; food and beverage processing; hospitality and tourism; ICT and media services; mining, engineering, and fabricated goods; real estate; transport and logistics (ZSE, 2020). It is arguable that it fairly represents most of the major formal business sectors and industrial players in the country. This assertion is supported by the fact that more than 50% of the listed firms consists of groups, corporations, and holding companies with at least two divisions under each of them. By this, it was logically assumed that study outcomes can be fairly generalized to apply to the mainstream local business community.

Sampling techniques

Stratified random sampling was used for this study. This entails splitting the population into at least two mutually exclusive groups, each being uniform, relevant, and suitable in the study’s context, and then randomly choosing sample units from these (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016; Saunders et al., 2019; Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). Simple random sampling was then used to pick sample units from each stratum. In this study, the fifty-five companies in the population were divided into ten strata based on their industrial sectors as defined under the Study Population section.

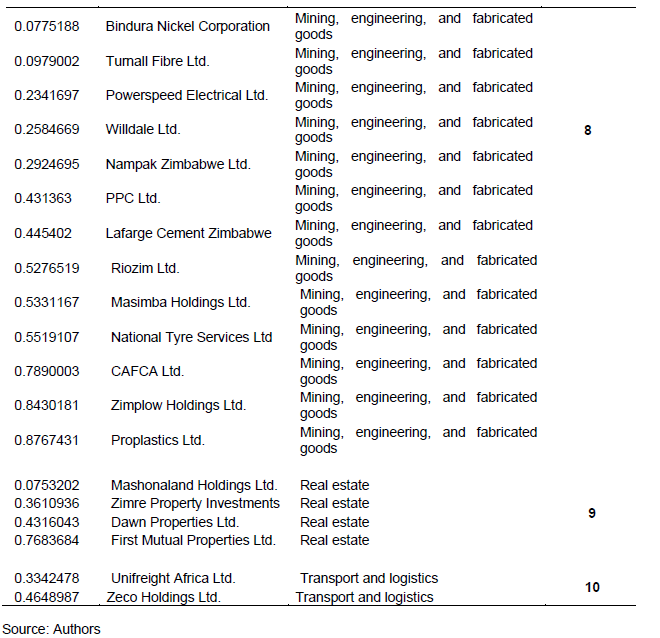

The unrestricted nature of simple random sampling suits it most for assuring the highest possible population representativeness whilst its nature of having the least bias offers the highest level of accommodation for generalization of study outcomes (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016). This made it suitable for this study which sought to draw a generalized conclusion on the relationship between change leadership and business survival in VUCA environments. Disproportionate stratified random sampling was used to reduce the chance of rare groups in the population being poorly represented in the final sample (Easterby-Smith et al., 2015). This meant drawing a bigger proportion of sample units from the smaller strata and vice-versa. It must also be noted that though the different individual companies and sectors were not affected to the same extent by COVID-19, they were all considered equally for this study to minimize outcome bias. A summary of the ZSE-listed companies categorized by their industrial sectors is given in Table 2.

Proportionally fewer sample units were drawn from the larger strata such as banking, finance and insurance and mining, engineering and fabricated goods than from the smaller strata such as diversified manufacturing and services, hospitality and tourism, ICT and printing services, and real estate. This was in line with the chosen principle of disproportionate stratified random sampling to enhance the sample representativeness of the target population.

Sample size determination

Sekaran and Bougie (2016) note that the sample size is crucial to sample representativeness for the generalizability of a study’s outcomes. They further note that sample size relies on the desired precision (confidence interval), the risk tolerable in predicting that precision (confidence level), population variability, and the limits of cost and time. This study had limited time yet the sampling design had to target results as highly generalizable as possible (low bias) and a minimal margin of error in any claims (high precision). Easterby-Smith et al. (2015) state that trade-offs are inevitable in decisions concerning the tolerable levels of precision and bias - with the most logical choice being imprecisely right outcomes. The study sample was thus chosen for accurate population representation but with a lower than ideal precision due to its deliberately small size.

From the ten industrial sector strata noted in the sampling technique section above, the researcher studied a simple random sample of ten companies with one drawn from each stratum without replacement. The companies highlighted in each stratum on Table 2 represent the 10 sample units selected probabilistically using the random number generation and custom sort functions in MS Excel (UWEC, 2020). This selection entailed separately prompting MS Excel to generate and assign random numbers between 0 and 1 to each company for each stratum. The companies in each stratum were then sorted in ascending rank order by their assigned random numbers. The first company in each custom-sorted stratum was then selected as the random sample unit in that stratum to give an overall sample of ten units across all the strata. This sampling method thus gave each company an equal chance of selection within its stratum and across all other strata.

Data collection technique

A structured self-administered mail/online questionnaire was used for the collection of primary data from the study sample for the trading period of March to December 2020. A self-administered questionnaire involves the respondents’ direct engagement through reading and completing the questionnaire themselves (Bryman, 2012). The questionnaire was sent to the respondents by electronic mail (e-mail) and consisted of 7 questions with 3 being closed-end/open-end, 2 being open-end, and 2 being closed-end types. The respondents were requested to type in their responses and return their completed questionnaires by e-mail. The e-mail questionnaire was ideally chosen over the printed, physical type mainly due to the prevailing COVID-19 safety restrictions on physical visits to many company premises as well as the time and financial cost limitations for the study.

Forty (40) questionnaires were sent to the ten companies, together with a BUSE research support letter with a target of four respondents per company. For each sample unit (company), one respondent each was sought at the four managerial levels of top management (directorate), senior management (administrative/ executive management), middle management (supervisory), and junior management (operational). The coverage of all managerial levels was deliberately set to mitigate the potential bias from an exclusive focus on the strategic organizational level (top and senior managers) that is chiefly accountable and responsible for change leadership. For more reliable study outcomes, a balance between the responses of change leadership architects at the highest level and those of the change implementers and change subjects at lower levels was deemed necessary to minimize bias of opinions.

Research questionnaire validity and reliability

The internal consistency and reliability of each of the study questionnaire’s 3 Likert questions’ 16 items were checked by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha reliability indices for each question’s items using SPSS v.20. A minimum index of 0.70 is acceptable for the inter-item internal consistency to be deemed good enough for a sound question (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016). Question B2 on the negative impacts of COVID-19 on the viability of ZSE companies had 6 items with Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.933. Question B6 that determined the effectiveness of change leadership interventions made by ZSE companies for ensuring successful change had 4 items and Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.926. Question B7 checked respondents’ opinions on change leadership’s importance to business survival in a VUCA environment based on their COVID-19 experiences. Its 6 items had Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.815.

From the above outcomes, each question thus had very high internal consistency amongst its items, indicating significant overall soundness of structural content that provided for a credible survey. Further, with such results Chehimi et al. (2019) assert that “this indicates a very good strength of association and proves that the selection of the questions is suitable for the questionnaire purpose” (p. 1915).

Validity was checked via SPSS v.20 bivariate correlation analysis. A question item was deemed valid if its Pearson correlation coefficient was significant at either a=0.05 or a=0.01 and the 2-tailed test’s significance value [Sig. (2-tailed)] was below 0.05. The analysis found 75% of the 16 question items to be valid, giving the questionnaire notable study instrument validity.

Data analysis

A structured mail/online questionnaire was used for primary data collection from the study sample. It allowed exploratory and descriptive study through open-ended, close-end, and mixed-type questions. Archival research was used for secondary data collection from 2020company trading updates and other strategic publications. Thematic content analysis was used for qualitative data whilst SPSS v.20 was used for quantitative data analysis. The two hypotheses were tested using linear regression in SPSS v.20’s univariate analysis function. The test rejected the null hypothesis as the p-value of 0.583 was greater than 0.05, implying that it was non-statistically significant. A high positive Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R) of 0.939 implied a significant positive linear relationship (Statology, 2019) between the response variable of business survival in VUCA and the 4 predictor variables of change vision, change understanding, change clarity, and change agility. This meant that 93.9% of the business survival in VUCA is explained by or directly influenced by the quartet of predictors.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Research question 1: What were the impacts of the COVID-19 environment on the viability of ZSE-listed companies?

The study found that COVID-19 had balanced impacts on the viability of ZSE firms. This was seen in 48.9 - 55.6% of respondents indicating significant to very significant negative COVID impacts on 5 of the 6 assessed viability aspects – revenue, profitability, liquidity/solvency, logistics, and value/supply chains, and staff welfare. The 55.6% of responses were noted for revenue decline and resonates with ZNCC’s (2020) June survey on the impact of the first 21-day national lockdown. The survey noted that 52% of the 210 multi-sector private sector firms interviewed had revenue losses between ZWL$1m – 5m in that period. The mixed nature of businesses and models in the ZSE companies accounted for COVID-19’s mixed impacts on their viability as some firms thrived and yet others were hard-hit.

The study concluded that COVID-19 impacted the viability of ZSE companies in a balanced manner with some being negatively impacted and others positively disrupted. This resonates with the conclusions of UNIDO’s (2020) global survey on 49 nations which indicated mixed socio-economic impacts across 5 of the 6 parameters assessed in this current study. Further, it was concluded that ZSE businesses whose operations ride mainly on innovative and cutting-edge digital models are generally more resilient and can better adapt in the face of the deleterious effects of a VUCA environment, such as that of COVID-19.

Research question 2: How feasible were change and change leadership interventions deemed by ZSE-listed companies as necessary for survival in the COVID-19 era?

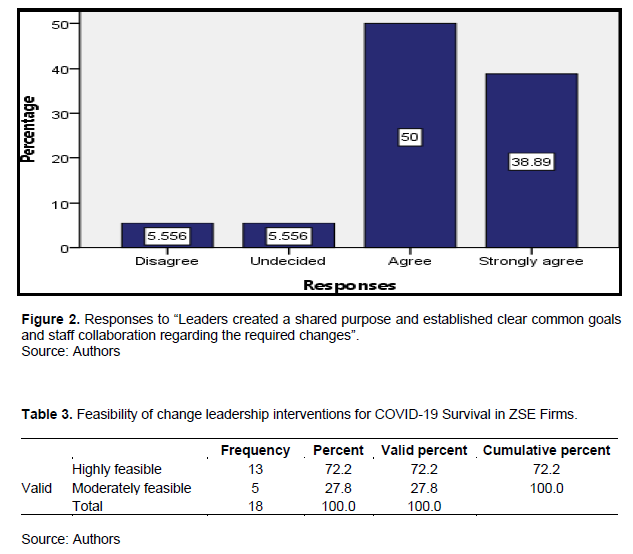

The research found that most of the change and change leadership interventions deemed by ZSE firms as necessary to survive in the COVID-19 era were highly feasible. This was reflected by 72.2% of the respondents citing this position, as shown in Table 3. The generally high feasibility was attributed to the responsible leadership capability of company boards and management teams which led to very practical resolutions on required change actions. This was supported by the fact that 100% of the respondents stated moderate to high feasibility for the interventions implemented in their companies.

The study concluded that practical and responsible leaders will cause necessary change and change leadership interventions to be feasible regardless of any prevailing adversities. This conclusion aligns with Isaah (2018)’s assertion that effective leaders are central to successful organizational change. Since responsible leaders partly practice transformational leadership (Sarkar, 2016), this conclusion also supports that by Herold et al. (2008) that exercising transformational leadership behavior increases employee acceptance and success chances of change initiatives.

Research question 3: What change and change leadership interventions were made by ZSE-listed companies for survival in the COVID-19 era?

100% of respondents reported that various key change and change leadership interventions were made in their 8 companies for survival since the March 2020 advent of COVID-19 locally. For example, Rainbow Tourism Group Ltd. leveraged digital technologies to launch a new online service, Gateway Stream. This innovation not only sustained and enhanced customers’ experience, but also boosted revenue in the absence of normal hotel stay-in and restaurant sit-in services. Further, most companies, including Bindura Nickel Corporation and FBC Holdings Ltd., invoked emergency business continuity plans and established special COVID-19 protocol teams to prioritize and enforce strict staff compliance to necessary and recommended health and safety measures. Hard-hit businesses in hospitality and tourism, such as African Sun Ltd. and Rainbow Tourism Group Ltd., even resorted to remuneration cuts to sustain operations in the wake of significant revenue reductions due to global lockdown impacts.

It was also found that most interventions across all companies reflected the change leadership aspects of agility and vision. This was linked to COVID-19’s novel nature which created a huge knowledge gap and many dynamics of viral spread and effects, making volatility and ambiguity its foremost features. That change vision was a key driver of many interventions made corroborates Wren and Dulewicz (2005)’s finding that the creation of a clear vision of the future after the change significantly influences change success.

The study concluded that change and change leadership interventions are inevitable for business survival in a VUCA environment such as that of COVID-19. This is due to VUCA’s consequent impacts on the internal and external environments in which businesses operate. The conclusion resonates with the assertion by Raghuramapatruni and Kosuri (2017) that thriving in such an environment demands constant adaptation to new business contexts as they emerge. It also agrees with Belias and Koustelios (2014) who concluded that change is an unavoidable part of organizational existence when dealing with an ever-changing business environment.

Research Question 4: How effective were the change and change leadership interventions made by ZSE-listed companies for their survival in the COVID-19 era?

The study found that most ZSE companies’ leaders exhibited a high level of the change vision aspect of change leadership. This was seen in 88.9% of the respondents (Figure 2) at least agreeing that their leaders created shared purposes and established clear common goals and staff collaboration on required changes. It also found that the leaders showed significant to very significant levels of change understanding, change clarity, and change agility as seen in 83.4, 72.2 and 83.3% of respondents respectively, at least agreeing with the survey statements that asserted those positions.

The study concluded that the change leadership interventions made by ZSE companies to make survival in the COVID-19 era a success were significantly effective and necessary if change for business survival will be effective in VUCA. This conclusion supports Higgs and Rowland (2000)’s finding that leaders’ activities during change implementation are vital to the change’s success. It also agrees with Doz and Kosonen (2008)’s assertion that organizational capacity for successful change demands effective leadership. It also supports Wren and Dulewicz (2005)’s conclusion that leaders’ behaviors and activities are strongly linked to the achievement of change success, especially resource management (change agility and understanding), engaging communication (change clarity), and empowerment (change agility).

Main research question: How critical is change leadership to business survival in a VUCA environment?

The study found that change vision is a very significant change leadership aspect needed for business survival in turbulent environments such as that of COVID-19. In fact, 94.5% of the respondents at least agreed with the survey statement that asserted this. It also found that change understanding is a very significant enabler of business survival in a VUCA climate as 77.8% of respondents at least agreed with the survey statement that implied this. Change clarity and change agility were also found to be very significant for VUCA business survival. This was noted in 88.9 and 83.3% of respondents, respectively at least agreeing with the respective survey statements that asserted those positions. 88.9% of respondents stated that other factors besides change leadership were key to survival in the COVID-19 era.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Knowledge of the contributory significance of change leadership to survival in dynamic and complex environments relative to the contributions of other factors enables a balanced appreciation of, and optimal approaches to, issues affecting overall business viability. Change leadership practice during the COVID-19 era was key to the survival of ZSE companies and is crucial to business survival in such turbulent environments. However, it is also concluded that change leadership alone is not a panacea to business viability challenges in such environments and must be completed by other interventions.

The aforementioned other interventions could include government mobilization and implementation of distressed business emergency rescue funding packages - such as the ZWL18billion stimulus package launched by the Zimbabwean government in response to COVID-19’s drastic impacts on business at large. Similarly, government policy mediations such as tax break grants, debt settlement moratoria, and cuts on business borrowing interest rates would also complement business’ internal change leadership efforts in exceptional VUCA episodes such as those brought on by COVID-19.

This study’s outcomes imply that business leaders must apply balanced strategies and approaches in addressing the varied impacts of VUCA phenomena that threaten viability. From the research, it is recommended that the Zimbabwean business sector lead the crafting, development, and implementation of multi-dimensional holistic initiatives for building and/or improving resilience in the broad corporate sector. These initiatives must consider force majeure and disaster preparedness, response, and recovery planning towards protecting and preserving financial and other socio-economic business investments. For instance, national industrial and commercial digitalization policy could be pursued seeing as it sustained firms like FBC Holdings Ltd. and Cassava SmarTech Ltd. during the studied COVID-19 period and beyond. Further, the creation of inclusive business change leadership education and awareness forums is prudent for capacitating business survival in dynamic and complex environments, particularly for small, medium and micro enterprises that often lack the requisite knowledge and expertise.

LIMITATIONS

The study entirely used virtual interaction and information searching due to COVID-19-driven restrictions and corporate control protocols on physical interaction and mobility. Further, the case study of several ZSE-listed firms gave challenges with getting the desired cooperation from some targeted respondents. So, this affects generalization of findings or necessitates taking them cautiously.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Bindura University of Science Education.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethical permission for this study was obtained from the Graduate School of Business at Bindura University of Science Education.

REFERENCES

|

A & DC (2014). The Leadership Challenge: Developing Leaders in a VUCA environment through LIVED™. |

|

|

Akindele RI, Oginni BO, Omoyele SO (2012). Survival of private universities in Nigeria: Issues, challenges and prospects. International Journal of Innovative Research in Management 1(2):30-43. |

|

|

Alexander D, Britton A (2000). Financial Reporting. 5th Ed. London: Thomas Learning Publishing. American Management Association. (1994). Google. |

|

|

ATO (2020). Business Viability Assessment Tool. [Online]. Available from: Business viability assessment tool | Australian Taxation Office. |

|

|

Akpoveta Y (2020). Change Leadership Defined! - Is it Still Only For a Select Few? [Online]. [Accessed: 6th October 2020]. Available from: |

|

|

American Management Association (1994). Google. [Online]. [Accessed: 25th September 2020]. Available from: |

|

|

Belias D, Koustelios A (2014). The Impact of Leadership and Change Management Strategy on Organizational Culture. European Scientific Journal 10(7):461. |

|

|

Burke WW (2008). Organization Change: Theory and Practice. 2nd Edition. Los Angeles: Sage Publishing. |

|

|

Burnes B, Hughes M, By RT (2016). Reimagining Organizational Change Leadership. Leadership 14(2):141-158. |

|

|

Burns JM (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper and Row. |

|

|

Cabeza-Erikson I, Edwards K, Van Brabant T (2008). Development of Leadership Capacities as a Strategic Factor for Sustainability. [Online]. [Accessed: 25th September 2020]. Available from: |

|

|

Chehimi GM, Hejase AJ, Hejase NH (2019). An Assessment of Lebanese Companies' Motivators to Adopt CSR Strategies. Open Journal of Business and Management 7(4):1891-925. |

|

|

Cummings TG, Worley CG (2009). Organizational Development and Change. 9th Ed. Oklahoma: Cengage Learning. |

|

|

Dinwoodie D, Pasmore W, Quinn L, Rabin R (2015). Navigating Change: A Leader's Role. Center for Creative Leadership. white paper. Available from: |

|

|

Doz Y, Kosonen M (2008). The Dynamics of Strategic Agility: Nokia's Rollercoaster Experience. California Management Review 50(3):95-118. |

|

|

Easterby-Smith M, Thorpe R, Jackson P (2015). Management and Business Research. 5th Ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Incorporated. P 80. |

|

|

El-Dirani A, Houssein MM, Hejase HJ (2020). An Exploratory Study of the Role of Human Resources Management in the Process of Change. Open Journal of Business and Management 8(1):156-174. |

|

|

Ford JD, Ford W (2012). The Leadership of Organization Change: A view from recent empirical evidence. In Research in organizational change and development. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. |

|

|

Hao MJ, Rashad Y (2015). How Effective Leaders can Facilitate Change in Organization through Improvement and Innovation: Global Journal of Management and Business Research. |

|

|

Hejase HJ (2017). Managing Change.Al Maaref University - Lecture Series, November 25, 2017. |

|

|

Hejase AJ, Hejase HJ (2013). Research methods: A practical approach for business students. Masadir Incorporated. |

|

|

Holsapple C, Li X (2008). Understanding Organizational Agility: A Work Design Perspective. |

|

|

Hughes M (2011). Do 70 per cent of all organizational change initiatives really fail?. Journal of change management 11(4):451-464. |

|

|

Issah M (2018). Change leadership: The role of emotional intelligence. Sage Open 8(3):2158244018800910. |

|

|

Johansen B (2007). Get there early: Sensing the future to compete in the present. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. |

|

|

Joy MM (2017). Leading in a VUCA World. Pallikkutam. [Online]. |

|

|

Kok J, Van Den Heuvel SC (2019). Leading in a VUCA world: Integrating leadership, discernment and spirituality. Springer Nature. |

|

|

Kotter J (2011). Change Management vs. Change Leadership-What's the difference ?. Forbes online 12(21):11. |

|

|

Kotter JP (2012). Leading change. Harvard business Press. |

|

|

Mack O, Khare A, Krämer A, Burgartz T (Eds.) (2015). Managing in a VUCA World. Springer. |

|

|

Maigher M (2018). What is the Meaning of Conceptual Framework in Research?. |

|

|

Makumbe W (2016). Predictors of effective change management: A literature review. African Journal of Business Management 10(23):585-593. |

|

|

McKinsey and Company (2019). Why Do Most Transformations Fail?. |

|

|

Obasan KA (2014). The Importance of Business Environment on Small Scale Businesses in Nigeria. International Journal of Management and Business Research 4(3):165. Available from: |

|

|

People Management Insight (2017). The Challenges and Opportunities Facing HR in 2017. |

|

|

Phillips S (2019). Managing Business Growth in Our VUCA World. |

|

|

Raghuramapatruni R, Kosuri S (2017). The straits of success in a VUCA world. IOSR Journal of Business and Management 19:16-22. |

|

|

Sarkar A (2016). We live in a VUCA World: the importance of responsible leadership. Development and Learning in Organizations: 30(3):9-12. |

|

|

Saunders MN, Lewis P, Thornhill A (2019). Research Methods for Business Students Eight Edition. Qualitative Market Research pp. 128-171. |

|

|

Sekaran U, Bougie R (2016). Research Methods for Business - A Skill Building Approach. 7th Edition. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 13, 43, 143-144, 241, 243-244, 276, 290. |

|

|

Statology (2019). What is a Good R Squared Value? [Online]. Available from: |

|

|

Thomas J (2003). Small Business Survival. Decision Analyst. |

|

|

UNIDO (2020). Coronavirus: The Economic Impact - 10 July 2020. [Online]. Available from: |

|

|

UWEC (2020). (Archives) Microsoft Excel 2007: Getting a Random Sample. [Online]. Available from: View |

|

|

Wilkinson DJ (2020). Change Failure Rates. What the Research Says: Do 70% of Change Programmes Really Fail? [Online]. Nevis: Oxcognita. |

|

|

Wren J, Dulewicz V (2005). Leader Competencies, Activities, and Successful Change in the Royal Air Force. Journal of Change Management 5(3):295-309. |

|

|

Yin RK (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Los Angeles, UK: Sage. |

|

|

ZNCC (2020). Sustainable and Flexible Economic Interventions to Address Covid-19. [Online]. Available from: |

|

|

ZSE (2020). Zimbabwe Stock Exchange - Listed Securities. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0