ABSTRACT

This study was conducted at the coastal villages of Kamikazi, Matemwe and Nungi of Zanzibar Island to understand the influence of tourism on the income generating activities of the local fishers along the Coast of Zanzibar Island. The methodology mostly involved face-to-face interviews and structured questionnaires. Results indicate that increasing tourism has impacted fishers twofold: (1) Parts of their fishing grounds were lost through development of tourist infrastructure such as resorts and hotels along the beaches area; (2) Some of the fishing gears were destroyed by tourists during activities such as diving, snorkelling, swimming with dolphins, and boat riding over inshore waters where fishing is actively taking place. Over the past twenty years of tourism development along the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island, the living conditions of the local fishers have remained low. The fact that fishers are partly losing the access to their fishing grounds is more likely to increase poverty among the fishing communities and thereby creating conflicts among the stakeholders. Employment in the tourism sector (resorts/hotels) has not been an option for the fishers because of their low educational background, except for menial jobs. The rapid development of tourism along the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island, while concomitant with a general increase in GNP of the island, has thus not led to an improvement of income generation activities of the local fishers.

Key words: Zanzibar Island, tourist, fishing.

Tourism is currently recognized as one of the biggest and fastest growing global industries (Gössling and Schulz, 2005). It continues to be the largest economic activity and the main source of foreign exchange earnings in many countries (UNWTO, 2013). The world has witnessed rapidly growing tourism in most coastal nations over the last two decades (Wood, 2002). Nature is an important factor for the tourists, and coasts provide possibilities for various nature-based recreational activities such as swimming, surfing, sailing, boating, fishing, diving, and sunbathing (Inglish, 2000; Urbain, 2003; Bodie et al., 2008). With the increase in the number of tourists traveling abroad for different purposes, the popularity of the coasts for tourist activities is increasing every year (Hall, 2001; Carter, 2003). According to Choi and Sarakaya (2006), tourism is seen as an effective vehicle for economic development that can bring significant economic benefits to countries, especially for developing economies through economic growth and poverty reduction. Researchers such as Lansing and De Vries (2006), Choi and Sirakaya (2006), Font and Brasser (2002), Shunnaq et al. (2008), and Lordkipanidze et al. (2005) emphasized tourism as an important means for income generation, employment and wealth in many countries. According to Reisinger and Turner (2002a) and Ryan (2003) the beauty of the sea, landscapes and natural resources in the coastal areas attract tourists, who by passing their holidays in these areas, compensate for the stress and boredom of their everyday`s life. However, Choi and Sarakaya (2006) stated that tourism can also contribute to environmental degradation and may lead to negative social and cultural impacts. Tourism development is often followed by diverse conflicts among stakeholders (Boissevain and Selwyn, 2004). Modern tourism is closely linked to the identification and development of a growing number of new destinations. The economic impact of tourism development especially for the coastal communities is seen as important (Loomis and Walsh, 1996; UNWTO, 1999). A new policy regime is required to secure an environmentally sound coastal development and a sustainable utilization of marine resources (Noronha, 2003; Bramwell, 2004). The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, 2001a) reported that foreign exchange earnings from international tourism reached a peak of US$ 476 billion in 2000, which was larger than the export value of petroleum products, motor vehicles, telecommunications equipment or any other single category of product or service. UNWTO (2009) argues that the economic growth brought through the development of the tourism industry goes hand in hand with an increasing diversification and competition among destinations.

Research area of study

Zanzibar is comprised of two main islands-Unguja and Pemba. The islands lie between latitude 04° 50” and 06° 30” South, and between longitude 39° 10” and 39° 50” East. Unguja is the main island and covers an area of 1,666 km2, while Pemba covers an area of 988 km2 giving a total land area of 2,654 km2 (Francis and Bryceson, 2001). The research for this study was conducted in the villages of Kizimkazi located in the southwest of Zanzibar, Matemwe in the northeast and Nungwi in the northern peninsula of Unguja Island (Figure 1). These three coastal villages were selected in consultation with experts at the Institute of Marine Science (IMS) and senior fisheries officials from the Zanzibar Department of Fisheries. The key selection criteria were as follows: firstly, they are the major fishing villages along Unguja; secondly, the development of tourism and recreational activities does not take place equally along the coast and differs from one village to another. The research sites had different numbers of tourist resorts, hotels and tourism-related activities. On Unguja, Nungwi is the most touristic village; it has more than 250 tourist hotels, guesthouses and bangalows. Matemwe Kigomani is the moderate touristic village with 110 tourist hotels, guesthouses and bungalows, while Kizimkazi Kigomani is the least touristically developed village with less than 70 tourist hotels, guesthouses and bungalows along the Coast of Unguja Island.

Interviews

The researcher used different participatory techniques in collecting the primary data in October and February 2011; within these periods, semi-structured interviews were conducted with local fishers in site with low tourism (n=61) and site with medium tourism (n=59), while site with high tourism (n=50), participant observations at the three sites as well as photographs were taken. The semi-structure interview with the local fishers’ is to elicit information on fisheries and tourism development related issues whether the local fishers have benefited from tourism development. The local fishers were asked to list and rank the most important types of income generating activities needed to fulfil their daily livelihood requirement before and after the development of tourism along the coastal villages. The respondents were asked open-ended questions on fisheries activities and tourism development, and their concerns about the future; the interviews takes 25 to 30 min depend on the responds of the interviewees. In-depth interviews were conducted to the official in the Zanzibar Commission of Tourism to investigate the strategy and policy use for the employment of the local fishers’ communities in the tourist resort/hotel in the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island. In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted to the resort/hotel managers/human resource manager to investigate the formality of employment of local fishers communities in the coastal villages, site with low tourism (n=3) and site with medium tourism (n=4), while site with high tourism development (n=6). The researcher held unstructured interviews with key informants in influential positions in the three coastal villages, and these include the local chiefs, teachers, employees of non-profit organizations and volunteers.

Secondary data

The researcher has analysed documents from the Department of Fisheries Development, Commission of Tourism, National Bureau of Statistic as well as information for the library at the Institute of Marine Science and other newspapers with information about the history of fisheries and tourism development in Zanzibar Island.

The study results derived from the interviews are presented on the following six aspects: (1) employment status of local fishers, (2) employment rates of local fishers households ‘in tourism sector, (3) income generating activities prior to tourism development and income generating activities after onset of tourism development, (4) perceptions of local fishers on the current households’ income, (5) income and expenditure of local fisher households, and (6) perceptions of the local fishers regarding tourism development.

Employment status of the local fishers in the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island

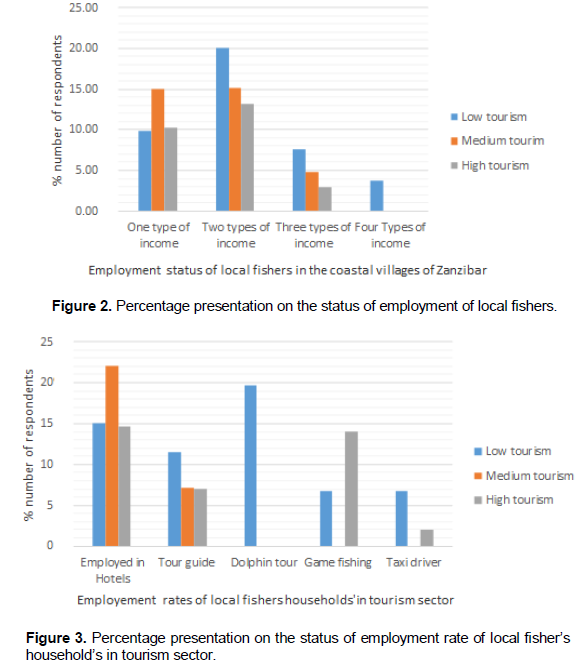

The occupations for the fishers were categorized into four sections in this paper, corresponding to the income generating activities mentioned (Figure 2). Interviews revealed that the majority of interviewed fishers had two types of income generating activities followed by the second high percentage of fishers who have a single type of income generating activity only.

In the study site with low tourism development have 6.71% of local fishers with three types’ of income generating activities; while 1.83% of local have four types’ of income generating activities. This is mainly because there are a number of sea-going tourism activities such as dolphin tourism and game fishing in contrast to the study site with medium and high tourism development.

Employment rate of local fishers’ households in tourism sector

The occupations status of local fishers’ households in tourism sector was categorized into four sections. There was a high rate of local fishers’ households in the site with medium tourism development employed in the tourist resorts/hotels (Figure 3).

In addition, the site with low tourism development has the highest number 19.70% of local fishers involved Dolphin tour related activities. On the other hand, the site with low tourism has a relatively high number 11.50% from the local fishers’ households were involved in tour guide activities. From the site with high tourism development, there is high number 14% of local fishers’ households involved in game fishing activities.

Income generating activities before tourism development

The households’ income generating activities of the fishers do not differ very much in the study areas. According to the responses of the interviewees, fishing was the main source of income, an activity that has been passed on from one generation to the next. The majority of fishers (57% at site with low tourism; 52% site with medium tourism and 43% site with high tourism) claimed that fishery is the most important activity, providing the highest income (Figure 4).

The next best activity for fishers (31% site with low tourism, 19% of the fishers in site with medium tourism, and 13% of the fishers on site with high tourism) stated that farming follows in importance. Seaweed farming tends to contribute significantly to the households’ income of the fisher-folks particularly at the site with medium tourism development. Other activities such rangers, bus conductors contributed less to the households’ income of the fishers.

Income generating activities after tourism development

The household’s income generating activities varies from one household’s to another as well as from one coastal village to another after the introduction of tourism along the coastal villages of Zanzibar. The majority of the fishers in the three sites of the research study indicated that fishing activity is the major source of income (Figure 5) for the local fishers’ over the last 20 years, after the development of tourism along the coastal villages. This research revealed that at least 57% of the coastal communities of Zanzibar Island were actively engaged in fishing and fish trading.

Seaweed farming is an important income generating activity of the fishers because 39% of the fishers’ households in the site with the medium tourism development were participating in seaweed farming. It was noted that the local communities along the coastal villages have diversified sources of their livelihood after the introduction of tourism. Among the diversification of the livelihoods strategy of the fishers’ was selling fruits and food which represents 17% at the site with low tourism. The livelihoods activities such as building and painting of houses, shop keeping, saloon dressing developed after the advent of tourism along the coastal villages of Zanzibar but contributes a small percentage to the fishers’ household income.

Frequency of fishing activity by the local fishers in the coastal village

The response of the interviewees varied from one fisherman to another as well as from one coastal village to another. It is interested that the site with high tourism development has the high percentage (76.0%) of local fishers often going out for fishing everyday; followed by the site with medium tourism development (42.37%) (Figure 6).

The site with low tourism development has a relatively low percentage (39.34%) of local fishers’ households going out for fishing every day. The research revealed that a relatively high number of locals in all three sites go out for fishing between five and six days in a week.

Perceptions of local fishers on the current households’ income

According to the responses from interviews (25% from the site with medium tourism, 34% of the fishers’ from the site with high tourism, and 21% of the fishers’ in the site with low tourism) claimed that their household’s income has increased after the introduction of tourism (Figure 7).

A smaller number of the fishers in the three sites stated that their household income slightly decreased after the introduction of tourism in the coastal villages. The assumption being made here is that the fishers’ monthly income ranges between 100 and 300 US$ per month and this depends on the catches as well as seasonality.

Income and expenditure of local fisher’s income

Thus, expenditure of local fisher households was divided broadly into six groups: support family, repair/build new houses, repair/buy new fishing tools, income spend to fund marriage in the family, buy cattle, and ‘support other activities’. According to the responses obtained (68% of local fishers in the study site with medium tourism; 64% in the study site of high tourism and 48% of local fishers in the study site with low tourism) claimed that their households income were spent on supporting family members e.g. buying food, paying school fees, medication, and clothing (Figure 8).

The second highest percentage of local fishers’ income was spent on repairing and/or buying fishing tools in the three sites of the study. At the same time, the local fishers were found to spend less of their household’s income on repairing and/or building of new houses, for wedding purposes as well as buying cattle’s. Twelve percent (12%) of the households’ income in the study with low tourism were spent on buying other items, such as bicycles, mobile phones, cigarettes and alcohol.

Perceptions of the local fishers regarding tourism development

The local fishers were asked about the kind of activities tourists conduct in the each of the coastal villages, and whether tourists’ activities have forced the local fishers to abandon their respective fishing ground along the coastal villages. Local fishers perceived that tourism related activities such as diving and snorkelling, boat riding, and dolphin tourism, have negatively influenced their fishing activities, which in turn have negatively impacted fishers households’ income generating activity. Photo 1 shows tourist activities in the coastal villages of the study.

The majority (62.3, 98.31, and 66% in low, medium, and high impact tourism sites) of the fishers interviewed perceived facing severe restrictions from accessing their ancestors fishing grounds in Mnemba Island and Kichwani after the introduction of tourism development. The local fishers reported that various tourists activities destroyed their fishing gears (such as nets or basket traps) and free the fish that were caught (Figure 9).

The local fishers were allowed to park their fishing crafts/canoes at least 200 m away from the tourist resorts and hotels. Moreover, the local fishers in the study site with low tourism revealed that there is a high competition between the tourists and the local fishers for fishing grounds. The tourists wanted to swim with the dolphins, while the fishermen want to catch fish. The tourist activities in the sea, particularly in the study site with low tourism, have caused conflicts with boat drivers who are used to take tourists into their fishing grounds.

Employment status of the local fishers in the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island

The income of local fishing households in the coastal villages of Zanzibar are affected greatly by types and the multiplicity of income generating activities, and other assets such as fishing boats, boat engines, fishing gears. The local fishers’ communities prefer going to the sea for fishing rather than to get employment in the resorts/hotels because of the poor payment in the tourist resorts/hotels. The majority of local fishers in the coastal village had opportunity of joining tourism related activities such as dolphin tour, sporting and tours guides. Employment in fisheries is likely to stabilize or decrease due to combinations of labour substitution by technological change and management measures to reduce over-capacity in the sector (World Fish Centre, 2011). In turn, the socio-economic status of local fishers in the coastal villages of Zanzibar is based on the fisheries productivity (Sesabo and Tol, 2005; Jayaweera, 2010).

Households income generating activities general patterns

Employment rate of local fishers’ households in tourism sector

This research revealed that less than 15% of local fisher households in the coastal villages were employed in resorts/hotels at the low positions such as cleaner, gardener, security guard, cooks and laundry services. The local fishers in the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island have never depended on single source of income generating activities; however the advent of tourism development have benefited a few local fishers’ households in the coastal villages. Future emphasis should focuses on the review of the current policy regime to improve the working conditions of the local people as well as payment systems in the tourist resorts and hotels. Mill and Marrison (1999) and Edgell (1999) revealed that tourism increased the chances of employment and hence development of income generating activities. McIntyre (1993) describes that the hosting communities received different kinds of benefits from tourism, which lead to an improved quality of life for residents. Findings of this research confirm those reported by Lange and Jiddawi (2009) who showed that the local communities along the coast of Zanzibar receive only 20% of income from tourism, while 80 percent of income from tourism related sector goes to stakeholders outside local communities. Gossling (2003) revealed that 50% of local communities participate in tourism related activity in the coastal village of Kiwengwa. On the other hand, research conducted by Jayaweera (2010) stated that there is a low participation of local communities in tourism related activities in the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island; higher participation of local communities’ households in tourism related activities were found in the coastal village with low tourism development. Researchers (Gossling, 2003; Lange and Jiddawi, 2009) underlined lack of language proficiency, low literacy rates and low skills of local communities to have greatly contributed to low participation of local communities in tourism related activity. Schilcher (2007) argued that instead of aiming at job creation in tourism related activities, policies should focus on improving incomes and working conditions of the local communities.

Fisheries

Discussion with local fishers in the coastal villages argues that the reason behind fishing being the main occupation in the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island was due to lack of land suitability for farming. On the other hand, the low level of income generating activities in the coastal villages has greatly contributed to the increase in the number of the local fishers. This research study concluded that the introduction of tourism along the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island has nothing to do with the steadily increase in the number of local fishers, since fishing as an activity in the Western Indian Ocean has a long history. Feidi (2005) states that the majority of the coastal communities in Zanzibar Island were poor to an extent that they cannot afford to purchase modern fishing inputs. For instance the author of this research noted that there is a high number of students dropping out from school, especially the adolescent. This high rate was caused by lacking financial support for education because most parents in the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island were poor.

Frequency of fishing activities performed by the local fishers

Fishing is arguably one of the hardest types of occupations in the world based on own experience, and the researcher twice joined the fishing expedition with local fishers’ in the coastal village to gain firsthand experience. “Our people are used to freedom. You go to work when you want in the morning; you come back home when you want. Some people put in a certain number of hours every day. Some people put in more. But you don’t have to punch a time clock. You are your own man. On the other hand, that requires a certain something about a person, because occasionally we see somebody who will need to work under a boss and who does not have the whatever-it-takes to carry on his business” (Ellis, 1986: 109). The fishermen like to fish because they think that they are the “boss for themselves” working independently, even for the captains who don’t own fishing crafts or the crews that work for the owner or the captain of the boats. The present study revealed that fishing effort along the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island has increased. Local fishers have intensified the frequency of fishing activity due to high demand of fish and seafood in the tourism resorts/hotels along the coastal villages. It is also interesting that the division of fishing labor in the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island varies from one coastal village to another. For instance, in the coastal village with low tourism development, fishing labor is divided in three categories. The first group often goes out for fishing very early in the morning at around 4:30 to 5:30am and the catches from this group of local fishers reaches at the landing site/auctioning centers’ at 11:00 to 12:00pm. The second group of local fishers’ often goes out for fishing in the afternoon between 12:00 and 2:00pm, and their catch reaches at the landing site/auctioning centers ‘at around 5:00 to 6:00pm. Most of the catch landed in the evening was sold to the women fish trader in the coastal villages. The third group of local fishers usually goes out for fishing in the evening between 5:30 and 6:30pm and the catch for this group of local fishers’ reaches at the landing sites/auctioning very early in the morning at around 4:30 to 5:30 am for marketing. The author of the research noted that the second group of local fishers was the most dangerous as most of group were young that joined fishing business recently with continues development of tourism in the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island. This group of youth was observed to use the most destructive fishing gears to catch as much fish, because of the high demand in the tourist resorts/hotels. The local communities in the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island name this category of young local fishers as “grouping fishing” because they often go out for fishing in large number range between 13 and 20 per fishing boat. Once this group of young fishers reached the respective fishing ground, they will set their fishing nets, and then afterward, all of them will go down diving chasing the fish in the direction where they have set their nets. These findings confirm what Jiddawi and Öhman (2002) found that, after the introduction of tourism development in the 1990s along the coastal villages of Zanzibar, the local fishers were highly motivated to concentrate particularly on demersal fish species such as snappers, groupers, emperors, parrotfish as their prices were relatively high and this has greatly contributed to the decline of catch per unit effort as well as fish sizes.

Perceptions of local fishers on the current households’ income

An increase of the household income of local fishers depends on the fishing inputs such as canoes/boat, nets, engine. The author of this research noted that the income earned by local fishers per trip varies according to season and the number and quality of nets used. The majority of local fishers along the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island often perform their fishing activities between 24 and 28 days in a month. Therefore, improvement of the income generating activities of local fishers is often seen as a central objective of fisheries management programmes, especially in developing countries (Lawson, 1984). The majority of local fishers’ households in the study sites often borrow money to meet their expenditure in the lean season for buying food and other necessary households’ items. The main reason for indebtedness of local fishers’ in the coastal villages depends on their income and expenditure pattern. According to DoF (2010) there is a rapid increase in the number of fishers’; the increases have affected the marine fisheries resources, and the income of fishers along the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island. Katikiro (2009) stated that the decline of environmental factors was said to be mostly caused by uncontrolled utilization of marine and coastal resources due to destructive fishing methods.

Income and expenditure of local fisher household income

The income and expenditure of households varies, depending on how large or small the households of local fishers in the Island are. The local fishers’ households that do not own fishing craft/gears kept on borrowing money from his master that owned fishing craft/gears to meet their household’s expenditures such as buying of food, school fees, health and clothes in the lean season from the period of April to October. The local fishers will refund the money borrowed to his master in the peak season from the period of November to February. Local fishers also received regular income as a share from the owners of the fishing crafts/canoes. These findings are in line with those of Crona et al. (2010), Platteau et al. (1992) and Russel (1987). The wholesalers/fish retailers are the major providers to local fishers with the capital on credit basis. The credit is extended as a means of securing priority access to products once harvested insuring a steady supply of goods. Crona et al. (2010) revealed that the relationships between local fishers and wholesalers/fish retailers become stronger through such loans for small-scale fisheries. Russel (1987) divided credit into two types; the first is the capital extensions for investment in the production process in fisheries, including financial support for investing in new and/or repairing of gears. The second type of credit constitute smaller amounts of capital recurrently issued as credit over extended periods of time, used to cover basic alimentary needs during the period of low income.

Perceptions of the local fishers regarding tourism development

Increased of tourism development along the Zanzibar Island has led to a sparing of coastal areas for touristic activities, through by which fishermen have lost access to parts of their traditional fishing grounds. As a consequence fisheries catches have declined and fishermen are being forced into alternative income generating activities for satisfying their daily needs. The investors used the beach areas to develop the infrastructures of tourist resorts/hotels and the local fishers’ faced serious restriction from accessing their fishing ground after the introduction of tourism and a good example for that is the Mnemba Island. According to Ali and Juma (2003), cited in Zanzibar Coastal Resources (2009), the advent of tourism development over the last 20 year was believed to be a wide-ranging issue contributing to both positive and negative impacts on the local community. Chachage (2000) cited in Zanzibar Coastal Resources (2009) revealed that the local fishers are losing access to the beaches, sea and other natural resources for their socioeconomic activity after the introduction of tourism development. Ap (1992) stated that it is important to understand the perceptions of local community in the first stage of tourism development, as this is considered to be the most significant aspect in planning and policy considerations for successful tourism development. According to Cooke (1982), the perceptions of the host community towards tourism are more favorably when the local community perceived they were able to influence decisions and outcomes related to development. Mowforth and Munt (2003) describe how local communities in Third World countries were exploited with only little means of control available for them to steer the direction of tourism development in their regions. According to Lange and Jiddawi (2009) states that lack of language proficiency greatly contributed to the limited number of young people working in tourist resorts/hotels along the coast of Zanzibar.

The introduction of tourism along the coast of Zanzibar Island has both positive and negative impacts on the activities of the local fishing households. The development of new tourism infrastructure such as construction/building of new resorts/hotels on the beaches area has restricted of local fishers accessing their respective fishing grounds had affected the income generating activities of their households. The living conditions of local fishers along the coastal villages of Zanzibar Island remain poor with almost no changes over the past twenty years of introduction of tourism development. Although the introduction of tourism has diversified the livelihoods of local fishers, the participation of local fishers’ households in ecotourism and tourism related activities were less significant as a results of poor educational background for the majority of local fishers’ households. In addition, the advent of tourism development in the coastal village has benefited the local fishers’ as their households’ income because of new market been created by for fish and seafood high in the resorts/hotels. The new market created after the development of tourism in the coastal villages has encouraged many households in the rural areas of Zanzibar to venture into the business of fishery industry. The increases of rural communities from the coastal villages in the business of fishery industry are likely to accelerate overfishing in the near future.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

This research project is supported by Germany Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). The author wish to extend his sincere thanks to the Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT) Bremen and Institute of Marine Science (IMS), Zanzibar.

REFERENCES

|

Ali MH, Juma MH (2003). Tourism Development and Local Community.

|

|

|

|

Ap J (1992). Residents' perceptions on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Res. 19(4):665-690.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bodie Z, Kane A, Marcus AJ (2008). Essentials of investments (7th Ed.). New York: McGraw Hill.

|

|

|

|

Boissevain J, Selwyn T (2004). Contesting the Foreshore: Tourism, Society, and Politics on the Coast. MARE Publication Series, 2. Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam. 320 p.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bramwell B (2004). Coastal Mass Tourism. Diversification and Sustainable Development in Southern Europe. Clevedon: Channelview Publications.

|

|

|

|

Carter DW (2003). Protected areas in marine resource management: another look at the Economics and research issues. Ocean Coastal Manage. 46(5):439-456.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Chachage SLC (2000). Environment, aid and Politics in Zanzibar, Dar es Salaam University Press.

|

|

|

|

Choi HSC, Sirakaya E (2006). Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tourism 27:1274-1289.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Cooke K (1982). Guidelines for socially appropriate tourism development in British Columbia. J. Travel Res. 21:22-28.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Crona BI, Nystrom M, Folke C, Jiddawi NS (2010). Middlemen, a critical social-ecological link in coastal communities of Kenya and Zanzibar.

|

|

|

|

Edgell DL (1999). Tourism Policy: The Next Millennium. Advances in Tourism Applications Series, Sagamore Publishing.

|

|

|

|

Ellis C (1986). Fisher Folk: Two Communities on Chesapeake Bay. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky.

|

|

|

|

Feidi C (2005). Ecosystem approaches to management and allocation of critical resources pages 313-345 in M. Pace and P. Groffman, editors. Successes, limitation and frontiers in Ecosystem science. Springer, New York, New York, USA.

|

|

|

|

Font X, Brasser A (2002). PAN Parks: WWF's sustainable tourism certification programme in Europe's national parks in R. Harris, T. Griffin, P. Williams & P, Sustainable Tourism: A Global Perspective, (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann). pp. 103-120.

|

|

|

|

Francis J, Bryceson I (2001). Tanzanian Coastal and Marine Resources: Some Examples Illustrating Questions of Sustain. Use pp. 76-102.

|

|

|

|

Gössling S, Schulz U (2005). Tourism-Related Migration in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Department of Service Management, Lund University, Sweden, Deutsche Gesellschaft f¨ur technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Giessen, German Gössling S (2003). The political ecology of tourism in Zanzibar. In: Tourism and development in tropical islands: political ecology perspectives. Edward Elgar: Cheltenham.

|

|

|

|

Government of Tanzania (2003). Indicative Tourism master plan for Zanzibar and Pemba. Final Report January 2003, United Republic of Tanzania.

|

|

|

|

Government of Zanzibar, Department of Fisheries (DoF) (2010). Fisheries frame survey conducted by the Department of fisheries statistic Zanzibar (unpublished report).

|

|

|

|

Hall CM (2001). Trends in ocean and coastal tourism: The end of the last frontier? Ocean and Coastal Management 44(9-10):601-618.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Honey M (1999). Ecotourism and sustainable development: who owns paradise? Island Press: Washington, DC.

|

|

|

|

IES (International Ecotourism Society) (2004). "What is Ecotourism?"

|

|

|

|

Inglish F (2000). Confecting seaside. In: F. Inglish (Ed.). The Delicious History of the Holiday. London: Routledge.

|

|

|

|

Jayaweera I (2010). Livelihood and diversification in rural coastal communities dependence on the ecosystem services and possibilities for sustainable enterprising in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Master's Thesis on Sustainable Enterprising Master's Programme 2008/09. Stockholm Resilience Centre Research for Governance of Social-Ecological Systems.

|

|

|

|

Jiddawi NS, Öhman MC (2002). Marine Fisheries in Tanzania. Ambio 31(7-8):518-27.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Katikiro RE (2009). Shifting Fishers Perceptions on the Environmental Baselines along the Tanga Coastline, Northeast Tanzania. A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in International Studies in Aquatic Tropical Ecology, Faculty for Biology and Chemistry.

|

|

|

|

Lange G, Jiddawi N (2009). Economic value of marine ecosystem services in Zanzibar: Implications for marine conservation and sustainable development. Ocean Coastal Manage. 52(2009):521-532.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Lansing P, Paul De Vries (2006). Sustainable tourism: ethical alternative or marketing ploy? J. Bus. Ethics 72:77-85.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Lawson R (1984). Economics of fisheries development (London, Frances Pinter) 283 p.

|

|

|

|

Loomis JB, Walsh RG (1996). Recreation Economic Decisions: Comparing Benefits and Costs (2nd Edition) Venture Publishing, Inc. State College Pennsylvania.

|

|

|

|

Lordkipanidze M, Brezet H, Mikael B (2005). The entrepreneurship factor in Sustainable tourism development. J. Clean. Prod. 13:787-798.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

McIntyre G (1993). Sustainable Tourism Development: Guide for Local Planners, World Tourism Organization.

|

|

|

|

Mill RC, Morrison AM (1999). The Tourism System: An Introductory Text (3rd Edition) Kendall/ Hunt Publishing Company, Dubuque, Iowa.

|

|

|

|

Mowforth M, Munt I (2003). Tourism and sustainability: Development and new tourism in the Third World (2nd Ed.). London: Routledge.

|

|

|

|

Noronha L (2003). Coastal tourism, environment, and sustainable local development. New Delhi: Teri.

|

|

|

|

Platteau JP, Nugent J (1992). Share contracts and their rational: lessons from marine fishing. J. Dev. Stud. 28:386-422.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Reisinger Y, Lindsay WT (2002a). "Cultural Differences between Asian Tourist Markets and Australian Hosts, Part 1". J. Travel Res. 40:295-315.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Russel DN (1987). Middlemen and money lending: relations of exchange in a highland Philippine economy. J. Anthropol. Res. 43:139-161.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ryan C (2003). "Recreational Tourism – Demand and Impacts". Clevedon, Buffalo, Toronto and Sydney: Channel View Publications.

|

|

|

|

Schilcher D (2007). Growth versus equity: The continuum of pro-poor tourism and neo-liberal governance. Curr. Iss. Tour. 10(2-3):166-193.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sesabo JK, Tol RSJ (2005). Factors affecting income strategies among households in Tanzanian Coastal Coastal Villages: Implications for Development-conservation initiatives. Working paper FNU-70.

|

|

|

|

Thorkildsen K (2006). Socio-economic and ecological analysis of a private managed marine protected area. Chumbe Island coral park Zanzibar. A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science (Management of Natural Resources and Sustainable Agriculture).

|

|

|

|

UN World Tourism Organization (1999). WTO News, July-August-September issue 3.

|

|

|

|

UN World Tourism Organization (2001a), Tourism Highlights 2001, Madrid, WTO.

|

|

|

|

UN World Tourism Organization (2009). About:

View

|

|

|

|

UN World Tourism Organization (2013). Tourism Year Book, Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture Republic of Maldives

|

|

|

|

Urbain JD (2003). At the Beach. University of Minnesota.

|

|

|

|

Wood ME (2002). Ecotourism: Principle, practice and polices for sustainability. United Nations Environment Programme.

|

|

|

|

World Fish Centre (2011). Aquaculture, Fisheries, Poverty and Food Security Working Paper. P 7.

|

|

|

|

Zanzibar Commission for Tourism (2011). Directory of Tourism Establishments in Zanzibar.

|

|

|

|

ZEB (2005). Tourism-the sleeping giant awakes: Zanzibar and its strategic tourism management. Zanzibar Econ. Bull. pp. 11-21.

|