ABSTRACT

It is widely believed that limited access of small scale farmers to agricultural credit is one of the key causes of rural poverty and a major constraint to adoption of innovations in Sub-Saharan Africa. Since the early 1960s, many strategies to access agricultural credits have been implemented with success. This study assessed the effects of warrantage, a community-based micro credit system, on poor small resource farmers’ income and livelihoods of the semi-arid area of Burkina Faso. Two broad socio economic surveys were conducted among 1040 farmers and 440 household heads. Data were collected from 58 inventory credit warehouses and 36 input shops established in the study areas. The results showed that the warrantage system is dominated by women farmers (who produce 60% of the stored harvests) and appears as the main source of agricultural credit. The profit (up to 140%) provided allows farmers to purchase external inputs such as inorganic fertilizers. This resulted in higher crop productivity and a substantial increase of farmers’ income which in turn improve farmers’ livelihood.

Key words: Inventory credit system, mineral fertilizer, staple crop production, small farmers.

Agriculture is the engine of economic growth in the Semi-Arid Sudano-Sahelian zone of West Africa. According to FAO (2012), it is practiced by 80% of the population and provides 35% of the countries’ gross domestic product (GDP). Despite the efforts of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is still facing a very large food deficit contributing to hunger, poverty and malnutrition (FAOSTAT, 2010; Schaffert, 2007). Food production is becoming insufficient because of the growing population. According to Adesina (2009) and Bationo and Wasma (2011), the decrease in agricultural productivity is linked to poor natural resources, unadaptable socio-economic and policy environment and to inappropriate climatic conditions. Agricultural soils in the Sahelian zone are characterized by predominantly sandy texture and low organic matter which results in very low fertility, particularly with respect to soil phosphorus and nitrogen (Buerkert et al., 2001; Van Straaten, 2011).

This systemic deficiency drastically limits crop growth and yield. Furthermore, these poor-structured soils are prone to runoff and erosion, resulting in the further depletion of their productive capacity (Bationo and Waswa, 2011; Sermé et al., 2016). To address land hunger in the West African Sahel lies in the intensification of agriculture and in the use of external inputs (specifically inorganic fertilizers) which could increase soil productivity (Van Keulen and Breman, 1990; Bationo et al., 2014). Although, integrated soil fertility management (ISFM) techniques have been developed by both national agricultural research systems (NARS) and international research organizations, these technologies have not been widely adopted by poor farmers. The reasons lie on the high costs of these technologies. Moreover, inputs availability is low and application rates of recommended fertilizers are not affordable to small farmers (Poulton et al., 2006; Adesina, 2009).

Three critical issues have to be addressed for fertilizers to successfully increase staple food crop productivity in Africa: fertilizer accessibility must be improved, affordability must be increased and the use of incentives must be effective (Poulton et al., 2006; Adesina, 2009; Sanginga and Woomer, 2009). In this perspective, important studies have been carried out by international research institutions and some NARS in West Africa to develop an effective technique known as fertilizer microdosing (ICRISAT, 2001; Aune et al., 2007; AGRA, 2014; INERA et al., 2014). This technique not only makes inorganic fertilizers to be more affordable to poor small scale farmers but also increases the efficiency of their use (Buerkert et al., 2001; Bagayogo et al., 2011). The microdosing technique consists in applying small doses of fertilizers in the sowing hills during planting or 10 to 15 days after planting. Combined to rain water harvesting techniques, it gives a quick start to young plants and can contribute to increase crop yield by more than 150%, even in rain deficit situations (Palé et al., 2009; INERA et al., 2014).

In spite of this significant technological advance, resource-poor small scale farmers are often unable to increase their production because of the lack of access to appropriate credit facilities. In the case of high production, there is a marketing problem of the extra production (Poulton et al., 2006). At harvest or immediately after post-harvest time, the market prices are low and farmers could not increase their income by selling their products to satisfy their needs and to purchase appropriate farm inputs for the coming cropping season. Many approaches were developed in African countries to improve the access of farmers to agricultural credit (Ouédraogo and Fournier, 1996; Zoundi and Hitimana, 2011; Anang et al., 2015). This was the case of Savings and Agricultural Credit Unions that appeared before independences era, first in English speaking African countries (Ghana, Tanzania) and then in West African French-speaking countries. The operator mode of these community-based structures was broadly in line with Western models (Ouédraogo and Fournier, 1996).

They were particularly characterized by their independence vis-a-vis the National Administrations and, the access to credit was reserved only to their members (Mondiale, 2007). Later, these structures were replaced by the National Agricultural Credit Offices and/or National Banks for Agricultural Development making more accessible credit to farmers. However, since 1980, these credit structures failed and the Popular Offices for agricultural credit took place in various African countries (Zoundi and Hitimana, 2011 Anang et al., 2015). These popular structures offer great support to farmers and to the informal sector activities (Buckley, 1997). To address the complex issue of facilitating credit to poor households, the international research institutions in collaboration with some West Africa NARS and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) developed a community-based micro credit approach known as Warrantage or inventory credit system (ICRISAT, 2001; Tabo et al., 2011; Adamu and Chianu, 2011; Sogodogo et al., 2014).

The organizations of farmer in partnership with a lending agency (micro financial institution, NGO, etc.) store their products at harvest in the appropriate warehouses and are issued with cash loans based on the value of their deposit. The loans enable them to address some urgent household financial needs and participate in collective fertilizer purchases. With this credit, farmers are able to carry out some income-generating activities (fattening of small ruminants, vegetable gardening and trading) during the off-season. Then, in agreement with the lending institution, farmers sell the stored grains at higher prices, 4-5 months after harvest, when the market supply begins to decline. Through this arrangement, they are able to earn substantial benefit that allow them to pay back their loans with interest (Adamu and Chianu, 2011; Tabo et al., 2011).

The warrantage system was implemented in some West Africa countries like Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger about ten years ago. It has been recently introduced in Benin (INERA et al., 2014). The accessibility to agricultural inputs, and the adoption of technological innovations could increase rain-fed crop production and household livelihoods; this rain-fed crop production could be also reinforced by the warrantage system (Adamu and Chianu, 2011; Tabo et al., 2011). This study aims to assess the implementation level of the warrantage system in Burkina Faso and to identify how this community-based micro credit system could influence (i) the attendance of input shops and inorganic fertilizer purchase, (ii) the adoption of fertilizer micro dosing technique, (iii) the rain-fed crop production and (iv) the household livelihood and food security.

Study area

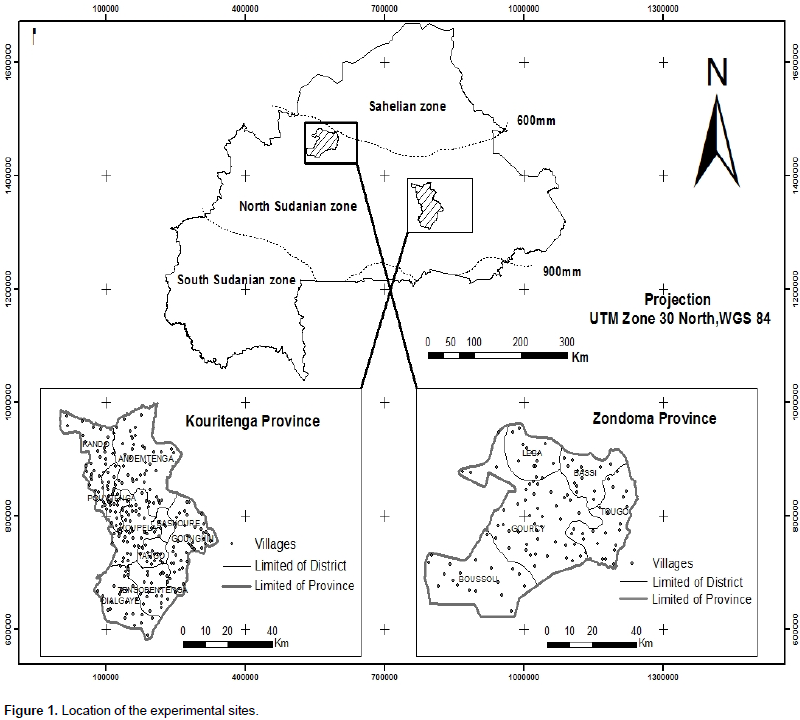

The study was conducted in two sites (Provinces), respectively located at the northern limits (Province of Zondoma) and Eastern Central (Province of Kourittenga) in the North-Sudanian zone of Burkina Faso (Figure 1). These areas are characterized by a clear woody Savannah, plagued by a continual environmental degradation caused by climate change and increasing land pressures. Soils are mainly sandy, poor-structured and strongly deficient in phosphorus and nitrogen, resulting in a low productive capacity. Agricultural production is mainly rain-fed and dominated by small-scale farmers in these sites. This production is subjected to the perverse induced-effects of climate change and climate variability. Then, this agricultural production is characterized by a lack of government support in both input supplies and credit systems.

Data collection

The study was particularly focused on data recorded from 58 warrantage infrastructures and 36 input shops which were established six years ago to support the dissemination of inorganic fertilizer microdosing technique. To assess the effects of the inventory credit system on farmers’ production capacity and livelihoods, two broad socioeconomic surveys were carried out 3 and 6 years after establishing the warrantage system. 1040 farmers and 440 household heads were sampled and constituted in a simple and randomized way in 12 villages in the study areas. An individual questionnaire was used to collect information on the links between this warrantage system and fertilizer purchase, micro-dosing technique uptake, farmers’ income and livelihoods.

Method of analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to calculate the mean values and the frequencies of the various variables. Therefore, Chi-square test was used to appreciate the relation between warrantage system and some variables like input shops visitation and the adoption of mineral fertilizer microdosing technique. Student's t test was performed to evaluate the induced-effect of the inventory credit system implementation on crop yield.

Descriptive statistics on the inventory credit system

In the northern and central eastern part of Burkina Faso, the survey showed that even if the amount of warrantage credit is not high, this micro-credit system provides 27% of farmers with financial resources. The average amount of inventory credit is 28,179 FCFA per producer and per year (Table 1). Certainly, the national financial institutions granted high total credit values, but the number of beneficiaries was very limited. A breakdown of the farmer’s population by gender showed the highest participation of women in this inventory credit system (57%) as compared to men (Table 2). Table 3 shows that the speculations involved in the inventory credit system were commonly rain-fed crops. The stored quantities vary according to both region and crop. Groundnuts, cowpea and rice were the most stored crops. 60% of the stocks were cowpea and groundnuts mainly from Zondoma.

Cost benefit analysis of the warrantage system

The economic analysis of adopting the warrantage system in 2012 showed that this system was a very profitable business. It allowed farmers to generate profits ranging from 90 to 183% (Table 4). A comparative analysis of the warrantage system on farmer’s income revealed that the storage of sorghum and millet is more profitable than other crops.

Effects of the warrantage system on rain-fed crop production and community-based livelihood

Relationship between the warrantage system and input shop attendance and/or input purchase

From the socio economic survey carried out on 1040 households, the results revealed that very few farmers visited an input shop and/or purchased inorganic fertilizer (Table 5); only 33% are aware of community based infrastructure; then 49% are involved in the warrantage system. The statistical analysis through the determination of Chi-square showed a significant link between these two variables. The adoption of the warrantage systems therefore, positively influences the attendance to inputs shops and the fertilizer purchase.

Relationship between the warrantage system and the micro dosing adoption

During the socio economic survey carried out in the 12 villages, it was shown that 32.5% of the villages applied the inorganic fertilizer microdosing technique. This proportion of the microdose adoption was increased by 94% when the villages practiced the warrantage system (Table 6). The Chi square calculation showed a strong relation between these two variables, indicating that the warrantage system is a determining factor in micro dosing technique adoption.

Effects of the warrantage system and the microdosing adoption by households

The socio economic survey showed that 55% of the households in the Eastern Central part (Kourittenga) did not practice the inorganic fertilizer microdosing technique. Table 7 indicated that only 36% of those who were not granted with the warrantage credit practiced the micro-dosing technique. When they were granted credit via the warrantage system, the proportion of households adopting this practice significantly increased by about 80%. This demonstrated the strong contribution of the inventory credit system to the microdosing technology adoption. In the same area, the inventory credit system was practiced by 33% of women cowpea producers. These women were more likely to adopt the microdose technology (36.7%) as compared to those who were not granted with warrantage credit (10%). The influence of the warrantage system on the decision to adopt microdose technique is highly significant and positive (Table 8).

Relation between the warrantage system and rain fed crop production

The comparison of crop yield averages indicates that women cowpea producers who were practicing the warrantage system obtained significantly higher yields as compared to those who were not granted credit. Table 9 indicates that this system increased cowpea yields by about 107%.

Relationship between the warrantage practice and farmer perception of livelihood

With the interview, summarized in Table 10, 43% of households noted some progress in their livelihood. It is the same for 49% of farmers who were granted credit by the warrantage system. But this increase is not significant because 41% of those who did not practice any warrantage system also noted an increase in their livelihood. Only 10% found their livelihood status is deteriorating whether or not they practice the warrantage system.

In the study sites, six years data analysis from 2009 show that the inventory credit system remains the main source of funds for the agricultural activities. The warrantage system appears therefore as a community-based micro credit scheme which is affordable to poor small scale households (Adamu and Chianu, 2011; Tabo et al., 2011, Sogodogo et al., 2014). Among other sources of funds, it is the most considered by famers (Poulton et al., 2006; Adesina, 2009; Zoundi and Hitimana, 2011), and more suited to the socio-economic conditions of poor farmers. Moreover, it is realized that at all level, (adoption and stored products) women are the ones practicing this activity most. Commonly, the stored products are represented by annual rain-fed crops (cereals, cowpea, sesame and groundnut). Cowpea and peanut mainly produced by women represent over 60% of the stocks. However, the market value of a given product lies on its social and economic importance at the selling period.

Therefore, sorghum and millet, the main staple foods of the region, provide higher benefits and ensure food security at food shortage period (beginning of the wet season). On average, the benefits due to the crops storage are close to 140% of the granted credit. These results express the determining role of this inventory credit system in the improvement of the socio-economic conditions of farmers as confirmed by a study of FAO (2012) in the southwestern part of Burkina Faso and in Mali (Sogodogo et al., 2014). The study also show that 57% of women actively participated to this warrantage system. This situation could be explained by the fact that rural women are commonly in charge of the household’s management. An inventory credit system that allows them to support income-generating activities (fattening of small ruminants, small trading and vegetable production) is welcomed and easily accepted. Furthermore, the high participation of women in that microcredit could be explained by the value of the deposit (cereal) as a guarantee, which is more affordable to poor small scale farmers.

The conventional credit systems require more guarantees (Roesch, 2004; Poulton et al., 2006; Adesina, 2009) that women are not able to provide due to their precarious economic situation. Generally, the warrantage system allows farmers to get considerable benefits through the increase of the price of stored products when the market supply begins to decline. Once the credit is repaid, the producer becomes owner of the products that he can sell at a better price according to the market demands. Another source of benefits got by farmers is the realization of income-generating activities that are not documented in this study. With the goal to support small poor farmers, mainly in facilitating the access to production inputs, the warrantage credit system is successful in empowering farmers to purchase inorganic fertilizer for microdosing technique. This result is consistent with the theory of agricultural credit. Daoudi and Wampfler (2010), Beaman et al. (2014), Banerjee et al. (2015) and Crépon et al. (2015) showed that the agricultural credit promoted the adoption of innovations.

This micro-credit strongly influences the attendance to inputs shops and therefore enables farmers to acquire fertilizer and other agricultural inputs (Buerkert et al., 2001; Tabo et al., 2011, Sogodogo et al., 2014). The study clearly showed that most of the farmers who carried out the warrantage system also adopted the inorganic fertilizer microdosing technique. With the objective to support poor small farmers, the warrantage system is a potential framework to inform and train cost-effective agricultural innovations. This positive effect of the warrantage system on the accessibility to fertilizers and to efficient fertilizer management technologies, consequently improves crop yields (Buerkert et al., 2001; Bagayogo et al., 2011; Tabo et al., 2011). In fact, farmers involvement in the warrantage system increased significantly, their income because of the benefits linked to crop storage and the income-generating activities (FAO, 2012; Sogodogo et al., 2014). In addition, food availability at the beginning of wet season (weeding period) contributes to improve manpower productivity, and consequently increase future rain-fed crop yields.

The problem of access of small poor farmers to agricultural credit resulted in a urgent need to find appropriate solutions to support agricultural production. From this perspective, this study clearly shows that the inventory credit system is an appropriate approach to address farmers’ poverty and food security. It is a community-based and annual-running tool that is simple to operate and only requires suitable partnership with micro financial institutions. Accordingly, it appeared as the main source of credit in the study area. In addition, the warrantage system is affordable to poor farmers, even to disadvantaged groups such as women. Thus this study showed that inventory credit system is more for female in Burkina Faso, because of their adhesion to the warrantage system. This activity enables them to earn money to conduct income-generating activities and address their household needs. The profit obtained from the warrantage system allows farmers to purchase external inputs such as inorganic fertilizers. This assertion was confirmed by the strong relation between this practice and the adoption of microdosing technique, resulting in higher yields and substantial increases in farmer income. Most of the households interviewed realized that their livelihood increased over a six-year period.

In spite of these advantages, the dissemination of the inventory credit system also has constraints which need to be addressed thus: (i) the real problems associated with access of farmers to agricultural credit cannot be tackled solely by capital injections but require fundamental structural changes of socioeconomic conditions that characterize this activity sector. Specifically, farmers need to be empowered so that they can establish themselves in win-win partnerships such as the warrant age system with larger financial institutions; (ii) existence of adequate warehouses at farmers’ organization level is a prerequisite to practice the warrantage system. The quality of products at selling times (and thus profitability) is strongly correlated with storage conditions; (iii) farmers’ organizations need real assistance from policy makers who must facilitate warehouse implementation and encourage win-win partnerships between farmers’ organizations and financial institutions; (iv) future research activities focused on the monitoring and evaluation of an inventory credit system must be intensified to seek more profitable and sustainable scenarios. After tackling these constraints, the warrantage system will appear to be a good pathway to combat both rural poverty and low agricultural productivity.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Canadian International Development Agency/International Development Research Centre (CIDA/IDRC) and the Alliance Green Revolution in Africa foundation (AGRA), through the collaboration of researchers from the University of Parakou (Benin); Institut de l’Economie Rurale (Mali); Institut National de Recherche Agronomique (Niger); the University of Saskatchewan (Canada) and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (Kenya).

REFERENCES

|

Adamu MA, Chianu J (2011). Improving African Agricultural Market and Rural Livelihood, through Warrantage: case study of Jigawa State, Nigeria. In: Bationo, A., Waswa, B., Okeyo, J.M., Maina, F., Kihara, J.M., 2011 (eds) "Innovations as key to the Green revolution in Africa", Springer Sciences + Business Media BV 2:1169-1175.

|

|

|

|

Adesina AA (2009). Africa's food crisis: conditioning trends and global development policy. Keynote paper presented at the international association of agricultural economists conference, Beijing, China, 16 August 2009.

|

|

|

|

|

AGRA (2014). Achieving Pro-Poor Green Revolution in Dry lands of Africa: Linking Fertilizer Micro dosing with Input-Output Markets to Boost Smallholder Farmers' Livelihoods in Burkina Faso. Rapport Final du Projet. 72p.

|

|

|

|

|

Anang TB, Sipiläinen TAI, Bäckman ST, Kola JTS (2015). Factors influencing smallholder farmers' access to agricultural microcredit in Northern Ghana. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2460-2469.

|

|

|

|

|

Aune JB, Doumbia M, Berthé A (2007). Microfertilizing sorghum and pearl millet in Mali Agronomic, economic and social feasibility. Agriculture 36(3):199-203.

|

|

|

|

|

Bagayogo M, Maman N, Palé S, Siriti S, Taonda SJB, Traoré S, Mason SC (2011). Microdose and N and P Fertilizer application rates for pearl millet in West Africa. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 6(5):1141-1150.

|

|

|

|

|

Banerjee A, Karlan D, Zinman J (2015). Six Randomized Evaluations of Microcredit: Introduction and Further Steps. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 7(1):1-21.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mondiale B (2007). Revue du secteur financier au Burkina Faso. Document Final 145p.

|

|

|

|

|

Bationo A, Waswa BS (2011). New Challenges and Opportunities for Integrated Soil Fertility Management in Africa. Innovations as Key to the Green Revolution in Africa. pp. 3-17.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bationo A, Kihara J, Waswa B, Ouattara B, Vanlauwe B (2014). Land degradation and agriculture in the Sahel of Africa: causes, impacts and recommendations. J. Agric. Sci. Appl. 3(3):67-73.

|

|

|

|

|

Beaman L, Karlan D, Thuysbaert B, Udry C (2014). Self-selection into credit markets: Evidence from agriculture in Mali. Center Discussion Paper, Economic Growth Center 1042:38.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Buckley G (1997). Microfinance in Africa: is it either the problem or the solution? World Dev. 25(7):1081-1093.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Buerkert A, Bationo A, Piepho HP (2001). Efficient phosphorus application strategies for increased crop production in Sub-Saharan West Africa. Field Crops Res. 72:1-15.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Crépon B, Devoto F, Duflo E, Parienté W (2015). Estimating the impact of microcredit on those who take it up: Evidence from a randomized experiment in Morocco. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 1:123-150.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Daoudi A, Wampfler B (2010). Le financement informel dans l'agriculture algérienne: les principales pratiques et leurs déterminants. Cah. Agric. 19:143-148.

|

|

|

|

|

FAO (2012). Le warrantage de la COPSA-C dans le Sud-Ouest du Burkina Faso.

View

|

|

|

|

|

FAOSTATS (2010). Food balance sheets. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

View

|

|

|

|

|

ICRISAT (2001). ICRISAT Annual Report 2001 'Grey to Green Revolution'.

View

|

|

|

|

|

INERA, IER, INRAN, UP, UofS, CIAT/TSBF (2014). Integrated nutrient and water management for sustainable food production in the Sahel, Final technical report of IDRC Project N°106516, INERA Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. 101p.

|

|

|

|

|

Ouédraogo A, Fournier Y (1996). Les coopératives d'épargne et de crédit en Afrique. Historique et Evolution récentes. Rev. Tiers Monde 37(145):67-83.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Palé S, Mason SC, Taonda SJB (2009). Water and fertilizer influence on yield of grain sorghum varieties produced in Burkina Faso. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 26(2):91-97.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Roesch M (2004). Financement de la culture attelée et stratégies d'équipement. Rev. Elev. Med. Vét. Pays Trop. 57:191-199.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sanginga N, Woomer P (2009). Integrated Soil fertility Management in Africa: Principles, Practices and Developmental Process. Tropical Soil Biology and Fertility Institute of International Centre for Tropical Agriculture, Nairobi. 263p.

|

|

|

|

|

Schaffert RE (2007). Integrated fertility management for acid Savanna and other low phosphorus soils in Africa and Brasil. A seminar presentation at KARI Headquaters, Nairobi, Kenya, February, 2007.

|

|

|

|

|

Sermé I, Ouattara K, Ouattara B, Taonda SJB (2016). Short term impact of tillage and fertility management on Lixisol structural degradation. Int. J. Agric. Pol. Res. 4(1):1-6.

|

|

|

|

|

Sogodogo D, Dembélé O, Konaté S, Koumaré S (2014). Contribution du warrantage a l'accès des petits producteurs au marché des intrants et des produits agricoles dans les communes rurales de Klela, Fama et Zebala dans la région de Sikasso au Mali. Agron. Afr. 26(2):167-179.

|

|

|

|

|

Tabo R, Bationo A, Amadou B, Marchal D, Lompo F, Gandah M, Hassane O, Diallo MK, Ndjeunga J, Fatondji D, Gerard B, Sogodogo D, Taonda JBS, Sako K, Boubacar S, Abdou A, Koala S (2011). Fertilizer Microdosing and "Warrantage" or Inventory Credit System to Improve Food Security and Farmers' Income in West Africa. (Eds A. Bationo, B. Waswa, J. M. Okeyo, F. Maina and J. M. Kihara). Springer Netherlands. Innovations as Key to the Green Revolution in Africa. pp. 113-121.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Van Keulen H, Breman H (1990). Agricultural development in the West African Sahelian region: a cure against land hunger? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 32:177-197.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

van Straaten P (2011). The geological basis of farming in Africa. In: Bationo A, Waswa B., Okeyo J.M., Maina F., Kihara J.M., editor. Innovations as Key to the Green Revolution in Africa: Springer. pp. 31-47.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zoundi SJ, Hitimana L (2011). The Challenges Facing West African Family Farms in Accessing Agricultural Innovations: Institutional and Political Implications. In Andre Bationo, Boaz Waswa, Jeremiah M. Okeyo, Fredah Maina, Job Maguta Kihara (2011) (eds). Innovations as Key to the Green Revolution in Africa. pp. 49-62.

|

|