Migration is one among the many livelihood strategies that households employ to diversify their sources of livelihood. Remittances that are channeled by migrants play an important role in improving the living standard of households, and reducing their level of vulnerability. This study discusses the impact of international remittance on the livelihood of the rural poor in Tehuledere Woreda, Northeastern Ethiopia. Qualitative and quantitative data have been generated for the study. The methodology employed structured household surveys, key informant interviews and individual narratives from case studies. Results indicate that households with different demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are beneficiaries of remittances. There has been considerable change to household consumption, asset accumulation and investment among recipients. Therefore, remittances have had profound impact on reducing the vulnerability of culprits of various hazards. Neighboring families and/or friends have also benefited from these remittances during time of need. On the other hand, there is evidence that in certain cases remittance triggers conflict among members of the receiving households. To assure sustainability, some recommendations have been made. First, households of remitters should strive to engage in diversified livelihood activities to reduce their dependency on remittances. Second, the transaction cost of money transferred needs to be reduced. Thirdly, the society needs to develop the culture of savings and investment than mere consumption. Fourthly, there should be efficient and effective access of financial intermediaries that can deliver remittance services to individuals at the right time at a reasonable service fee.

Rural households in developing countries earn income from diverse allocation of their assets among various income generating activities (Ellis, 2003). The reasons behind diversification of livelihood activities include diminishing returns from increasing investment in certain activities, lack of or unstable markets to minimize, cope with and spread risk, to create consumption and labor smoothing, adaptation to income challenges over time (Ellis, 2003).

Migration is one among the many livelihood strategies that opens up access to diversified livelihood opportunities. Migration reduces the level of vulnerability of households, helps to preserve, form and accumulate capital and minimizes the vulnerability of households to sudden catastrophes and prevents them falling into the low level living conditions what is called ‘living on the edge’ (Ellis, 2003).

Earnings from remittances can strengthen livelihoods through investment in land or land improvements, purchase of cash inputs to agriculture (Carter, 1997), investment in agricultural implements or machines, education (Francis and Hoddinott, 1993), and in assets permitting local non-farm income to be generated (Dugbazah, 2007).

The rise in remittances and the increased number of migrants are two important discussion points in the arena of development (Albert et al., 2009). International migration is one of the most important factors affecting economic relations between developed and developing countries (Richard et al., 2005). Developing countries receive a considerable amount of the share of global remittances (Mohapatra et al., 2007).

Ethiopia is one of the poorest countries in the world with 27.8% of the population living below the poverty line in 2011/12, and the level of poverty is more severe in rural areas than in the urban (MoFED, 2012). Recently, the flow of remittances in this country is growing and playing fair share in reducing poverty. Remittance flows of Ethiopia have steadily grown from 4 in 1997 to 47 million US dollars in 2003, and reached 172 million US dollars in the 2007 (World Bank, 2008).

Remittance inflows covered 1.3% of gross domestic product (GDP) of Ethiopia in 2009. However, despite its large migrant population, Ethiopia has not fully tapped its potential. The remittance flows to this country is only one-sixth of its potential; covering just eight percent of the nation’s budget deficit (World Bank, 2011). If the potential level of remittance were to materialize, it would exceed the level of Official Development Assistance, which reached 3.3 billion US dollar in 2008. Informal remittance flows to the country also appear to be significant and remittance inflow data for Ethiopia vary by source. The major source countries for remittances to Ethiopia in 2008 were the United States, and the Gulf cooperation countries and in 2010, the United States, Israel, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait (World Bank, 2011).

Tehuledere Woreda is found in North East Ethiopia. Agriculture; both crop production and animal rearing, have being adversely affected by many factors, some of which are natural and anthropogenic. The most repeatedly occurring natural hazard is erratic rainfall, and there is also occurrence of pest and diseases. Human induced problems include shrinking farm size and declining soil fertility; the poor market access for livestock and livestock products, and scarcity of improved technologies also affect the viability of agricultural practices (TWOARD, 2013).

Partly in response to those constraints, the population of the area employs international migration as an alternative livelihood strategy. This study aims at exploring the impact of international remittance on the livelihood of rural households in Tehuledere Woreda, Amhara Region.

This study would contribute to adding insights on the role of remittance inflows to the development of Woreda. The study will also draws some pertinent policy ideas through which the challenges of remittance can be addressed.

Review of conceptual and empirical literature

The concept of remittance consists of inter-family transfer, personal investment transfer, collective transfer and social security transfers (IMF, 1993). It refers to a person-to-person flow of money; from the migrant to their families and/or friends and is a transaction initiated by individuals living or working outside their country of birth or origin (OECD, 2006). The type of remittances and the livelihood status of the recipient household determine the sector to where remittance should be spent. Inter-family transfer, which is the central focus of this article, typically has immediate benefits for the individuals in fulfilling daily subsistence (Albert et al., 2009).

The increasing amount of remittance is helping developing countries to lower poverty, to increase saving and investment, to augment and smooth consumption and to improve human capitals (Makhlouf and Mughal, 2011). Remittance plays a great role in reducing rural poverty through financing health and education; in easing of credit constraints for small businesses. It serves as a source of insurance during natural calamities and human-induced shocks and to the improvement of current account sustainablity and credit worthiness (Ratha, 2012). Regarding the contribution of migration to livelihood improvements, Rosemary et al. (2008) stated:

“Globalization and migration are rapidly transforming traditional spheres of human activity. The work of rural families is no longer confined to farming activities, and livelihoods are increasingly being diversified through rural-to-urban and international migration.”

Remittance has been an important source of foreign exchange for Ethiopia, and it is larger than the export earning of the country in terms of its foreign exchange generation capacity. A noticeable amount of out migration in Ethiopia started during 1970s following the political unrest and revolution. The type of migration that was dominant during that time was the migration of urban elites and politicians who sought refuge in western countries. However, migration later became an aspiration of urban people mainly for economic reason (Alemayehu et al., 2011).

After the mid1980s, rural peasants also began flocking to the Middle East and the Gulf region in search of jobs and better payment. The total numbers of Ethiopians living abroad vary by source. However, according to the Population and Housing Census of the country conducted in 2007, close to 120 thousand Ethiopians left their country every year and over one million Ethiopians are believed to reside abroad (Aredo, 2005). Remittances have covered 1.3% of the country’s GDP over the last 30 years. Between 1977 and 2003, remittance flows have steadily grown from 4 million to 47 million US dollars per year and reached 172 million US dollar in the 2007 (World Bank, 2011).

The National Bank of Ethiopia (2010) shows that the amount of money that Ethiopia received from different parts of the world in 2011 was from North America (483.7 millions of US dollar), Asia and Middle East (355.7), Europe (222.3), Africa (48.5), Australia (35.0), and the rest of the world (202.1). The total amount of money that was obtained through remittances from different parts of the world during this period was 1,347.3 million of US dollar. However, besides its positive impact, remittance may increase social tension within the household both among those at home and within migrants who are remitting the money (Rodriguez, 2000).

There are certain remittance related studies that are conducted at different levels. International migration and remittance significantly reduce the level, depth, and severity of poverty (Richard et al., 2005, Bichaka and Christian, 2008, Sanjeev et al., 2008). These studies also pointed out that remittance has a direct poverty mitigating effect. It is an extremely important source of foreign exchange for Ethiopia, and improves the living standard of receivers at the micro level (Alemayehu et al., 2011).

Nonetheless, the main focus of most previously done studies was at macro level, and they are mostly inclined towards the urban population and urban poverty. The role of remittances in the reduction of rural poverty is an issue that deserves investigation. In the past, it was not common for the rural households to benefit from international remittances. The current trend of international migration in Tehuledere Woreda is different from the past. Recently, most rural households of the Woreda are sending member/s of their family abroad particularly towards the Middle East. The objective of this study is to assess the contribution of international remittances for the livelihood improvement of rural households in Tehuledere Woreda, Northeast Ethiopia (Figure 1).

Sampling strategy, data collection and analysis

The study was conducted in Tehuledere Woreda, Northeastern Ethiopia. The following two reasons were used to select this site: The Woreda is found in drought and famine prone areas of Northeastern Ethiopia where the considerable proportion of the population lives under chronic food insecurity and recently, international migration as a means of livelihood strategy is highly practiced by members of many households in the study site.

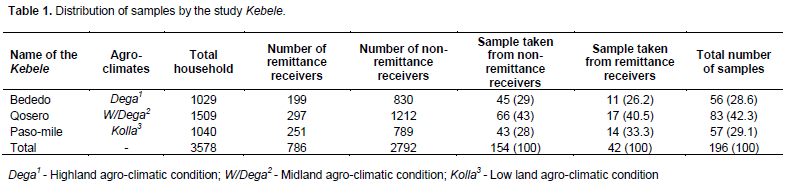

Kothari’s (1990) formula (with 0.5 estimated proportion of respondents, 95% confidence interval and 0.07 margin of error) were used to select the 196 sample households that were proportionally distributed for three sample rural

kebeles

[1] selected randomly from the three agro-ecological zones in the

Woreda. Moreover, samples of remittance recipients and non-recipients were allocated proportionally the households of specific

Kebeles under study. Then systematic random sampling technique was employed to select remittance receiver and non-receivers households. Accordingly, every 18

th households (identified by N/n)

[2] in all

kebeles from both remittance receiver and non-receivers were included in the sample as shown in Table 1.

The study employed various data collections techniques namely household surveys, key informant interviews for general descriptive information, case study narratives to understand processes and direct observations. Some secondary data supplemented the first-hand data. Structured interview was conducted based on the questionnaire designed for the purpose of the study. Most questions of the questionnaire were pre-coded and some open-ended questions such as age of the household head and the migrant, household size, land size and total stock of animals were entered and categorized at the stage of data analysis.

Key informant interviews were also conducted with Administrators and Development Agents of the three selected kebeles, and the Vice Administrator of the Woreda Agriculture and Rural Development office. Furthermore, case study households were interviewed to assess their livelihood histories and stories. Six remittance receivers who have achieved a relatively better life after remittance and six non-remittance receiver households have narrated about their livelihood situations. In addition, review of some secondary data and observations of some features such as topography of the study area, infrastructure and housing condition have been employed to complement the primary data.

The results of the survey are analyzed using descriptive statistics such as percentage, mean and chi-square. They are illustrated as tables. Chi-square test was employed to draw association between respondent’s characteristics in terms of remittance receiver or otherwise. Qualitative information was presented in various forms as interpretation of the observations, direct quotes and in certain cases in the form of case narratives.

[1] Lowest administrative unit in Ethiopia

[2] ‘N’ is population size where as ‘n’ is sample size taken from the population.

Demographic and socio-economic features

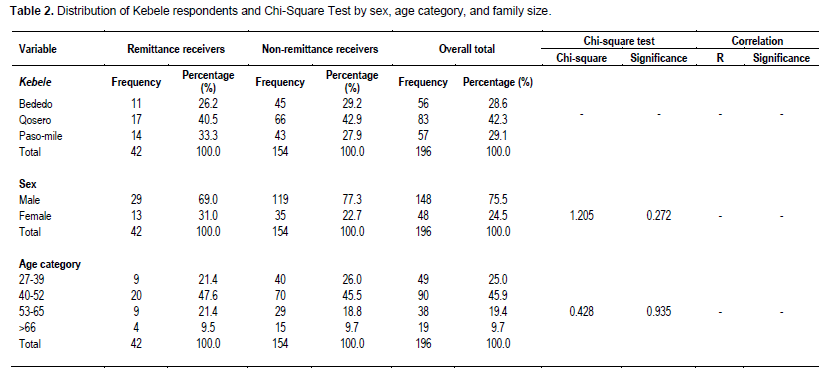

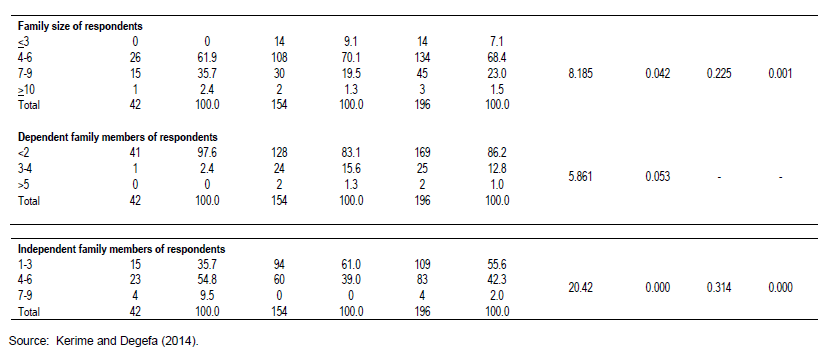

Out of the whole respondents, 42.3% were from Qosero, 29.1% from Paso-mile and the remaining 21.4% are drawn from Bededo Kebele. Some 28.6% of respondents were remittance receivers, and 78.6% are non-receivers. Majorities that is, 75.5% of respondents are males and 24.5% are females. About 69% of the remittance receiver’s household heads are males, and the remaining are females. Chi-square test was used to test the association between sex of the household head who were remittance receivers and those who were not, and there was no statistical significant association between the two (Table 2).

Age of the household head was one among the many determinants of migration and remittance due to its impact on the age composition of household members. The larger proportions of respondents (45.9%) were within the age group of 40 followed by those in the age bracket of 27 to 39 years (25%). Similarly, nearly half of household head of remittance receivers are concentrated within the same age group of 40 to 52 (47.6%). However, no association between age of household head and being remittance receiver was found. The number of family size within a given household has its implication and impact for remittance through its effect on migration. It will have impact on the number and availability of adult family members that can migrate and remit to the family left behind.

The great majority (68.4%) of the respondents had 4 to 6 family members, the proportions of households with family members below 3 and more than 10 are small in both remittance receiver and non-receiver respondents. However, no association was found between family size and households being remittance receiver or not (Table 2). Qualitative data revealed that, the availability of family members capable of involving in migration is a good determinant for households to benefit from remittances.

“…the main determinant of households to be benefited from remittance is the existence of family member/s whose age and sex permitted to be demanded by people in destination countries. Those remittance non-receivers are households who do not have a daughter whose age is above 18, whose daughters have a good job and/or restricted from migration with certain medical problem. Household head that do not have daughters to send them abroad are sending their wives (if their age is within 20 and 30s). Recently, it is common to see a father with his children performing domestic work due to migration of wives that left their husband and children behind. Therefore, the migration of married females is becoming a common experience for many households who do not have able daughters to migrate.” (A poor non-remittance receiver in Qosero)

Generally, the results of both quantitative and qualitative data have revealed that the composition of family members in terms of age and sex determine whether a household has remittance income source or not.

Education level of respondents

Majority of household heads both from remittance receivers and non-receivers are formally uneducated. The low literacy levels of respondents was generally expected given the context where the research has been conducted, being rural households. Based on key informants, the coverage of schools and educational facilities were very limited in the rural areas. Therefore, it should not mislead us to a conclusion that households with no or limited education are the more beneficiary of remittance. No association between education level of household heads and being remittance receiver or not was found.

Not only was the education level of the head of the household but also the level of education of remitters was generally low. The maximum achievement of education for remitters is high school grades. Out of the total 42 remittance receiver respondents, 14.3, 4.8, 42.9 and 38.1% of their remitters are unable to read and write, primary first cycle (1 to 4), primary second cycle (5 to 8) and high school, respectively in terms of their education.

This is partly due to limited requirement of high academic qualifications in the destination of migrants and unskilled sectors that they are employed in. All remitters employed as a housemaid in their destination. It is claimed that to read and write may be enough for them to accomplish their tasks.

Socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents

The households in Tehuledere, Northeast Ethiopia, at all levels of economic status will engage in migration of certain family members. Previously, the main constraint to migration was lack of initial capital for travel. But recently, it has become common to cover this cost either through borrowing from families and/or friends or from brokers. This trend eases the financial constraint of migration for poor households. Recently, many poor households are benefiting from remittance. But in most cases, households who are very rich do not prefer to employ migration as a livelihood strategy due to its certain risks and uncertainties. So, if the household has sufficient resources and means of livelihood, sending certain family members abroad and worrying about them day and night is not commendable.

The source of capital for migration may reflect the economic status of the respondents. The source of finance for 52.4% of respondents was own asset either from saving, sale of livestock or others. The cost of migration for 31% of migrants was covered by borrowing from family and/or friends. Informal financial institutions also cover the cost of migration for 7.1% of migrants and brokers and earlier migrants together cover the cost of 9.6% of migrants. Households who can cover the initial cost of migration and those who cannot engage in migration of certain family member/s are beneficiary of remittance.

Respondents were also asked about their total stock of animals and their corresponding estimated market value. Majority of sample households have less than four livestock. In rural areas, livestock are important assets that have a direct relationship with economic status of households. Therefore, it was assumed that it will have association with being remittance receiver or non-receiver. But association that exists between them was statistically insignificant.

Land is the most important natural capital for rural population. The amount of land for a given household has implication and impact for its economic status. Therefore, there was a room for respondents to tell the size of land.

that the household holds. But no association between the amount of land for a household and remittances being received was found (Table 3). This might be due to the fact that those who hold sufficient land are less likely to involve in sending family members abroad. The other explanation could be that unlike other forms of assets, land purchase is prohibited under Ethiopian policy.

The amount of production for a given household also implies the economic level of households. The amount of household’s production can feed family members throughout the year or only for certain months. Households in both categories engage in migration of certain family members and are beneficiary of remittances. Most respondent’s produce crop but cannot feed its members throughout the year, and no association between the amount of production and households being remittance receiver was found.

Some characteristics of remitters

The sex of remitters is totally female. Therefore, the migration of females in the Woreda is becoming a common experience. The maximum achievement of education of remitters is high school. Their age is mainly concentrated between 19 and 28 (81%). Saudi Arabia was the most common place with 55% of remitters followed by Kuwait (19%) and United Arab Emirates (16.7%). A few numbers of remaining remitters were from countries such as Qatar, Oman and France. As far as the respondents’ relationship with their remitters is concerned, 76.2% of the remitters were the daughters of the household heads, 16.7% their wives, 4.8% their sisters and 2.4% of remitters were their granddaughters.

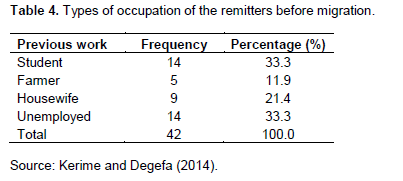

Most parts of migrants were students (one third) and unemployed (one third) before their migration followed by

house wives (21.4%) and farmers (11.9%) (Table 4). It was also learnt that teachers in elementary school have involved in migration. Elementary school teachers were leaving their job and migrated out either legally or illegally due to dissatisfaction with their work and income.

Recently, remittance is becoming important source of income for many households. All remitters have been migrated after 2008 such that 59.5% of the remitters migrated in 2012 and 2013 while 28.5% did so during 2008, 2011 and 2013/14. Therefore, mass migration of females towards the Middle East is a very recently phenomenon as a livelihood strategy. The findings show that there has been an increasing trend of migration in 20013/14. Based on Administrator of the Woreda, there was reduction of migration of females in 2013/14. Certain countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have recently stopped recruiting house maid workers from Ethiopia, and there is a temporary ban as a result of certain disagreements between the workers and the employers. This condition created a fear both for both the migrant and their families.

Pure altruism and pure self interest covers a considerable proportion behind the motivation of migration. The migrants send money for their family’s welfare and for themselves (for the purpose of saving) (Table 5). Migrants may send a certain proportion of their income for their family and save the remaining for themselves. This enables migrants to assist their families left behind as well as to save certain proportion of income for their future use. At the initial stage, the family will cover the cost of migration and later the migrant will remit the family during times of problems. This is an implicit family agreement.

Economic and social impacts of remittance

Economic impact of remittance

Remittance plays a great role in reducing rural poverty through financing health and education, ease of credit constraint for small business that serves as a source of insurance during natural calamities and human-induced shocks, improvement of current account sustainablity and creditworthiness in the world (Ratha, 2012). Even if the amount of remittances that the poor receive is low in absolute term, it makes a substantial change in the relative livelihood of poor households (Ellis, 2003). The result of this study also revealed a similar finding.

Migration in the studied area was employed by the decision of the migrant family and the migrants themselves. Taking into account the livelihood context and trend of the study area, nearly a half (49%) of the total respondents including both remittance receivers and non-receivers agreed that migration is appropriate livelihood strategy. From a total 42 remittance receiver households, 59.5% agreed on the appropriateness of migration. But the remaining 40.5% sampled remittance receivers had disagreed on its appropriateness while they had migrant family members. The chi-square result for perception of household head towards migrations indicates that there is no statistically significant association with households being remittance receiver or not. The whole sample respondents of remittance receivers have reported that the household had remitted by the migrant at different periods either regularly at every two to six months interval (83.3%) or on irregular

basis (16.7%).

Remittances covered 10 to 25% of the income of most parts of respondents (54.8%), followed by 25 to 40% for 28.6% of respondents and for 7.1% of sample remittance receivers it generated their 40 to 55% of income. Remittance covered more than 55% of income for the remaining 9.5% of sample remittance receiver respondents. Therefore, remittance covers a considerable proportion of income for the receivers. About 85.7% of respondents indicated that household heads are those who the administrator of the remittances is the household head and 11.9% of the controllers were made up of remitters themselves.

Remittance increased the purchasing power of receivers. However, in some cases it has negative impact in triggering income inequality. It was also the source of tension between those remittance receivers and non-receivers. Remittance receivers were asked about the expenditure area of remittance and they had the opportunity to choose up to six items on which they expend. These expenditures are grouped into “consumption” and “asset accumulation/investment”. Which expenditure categories should constitute consumption versus asset accumulation is debatable, particularly when it comes to assets such as housing. However, for this presentation, the researchers have grouped them under the category of consumption using the following expenditures patterns: expenditure on consumption goods in general and debt payments. Asset accumulations comprise construction or repair of housing, start/expand a business, education and health expenses.

The future and immediate benefit of remittance varies according to different types of remittances. Inter-family transfers typically have immediate benefits for the individuals in fulfilling daily subsistence (Albert et al., 2009). The most common expenditure area of remittance is consumption goods (42.9%) followed by construction of new houses and repairing of the existing ones. Health and education expenses also had their proportional parts in the remittance package (Table 6).

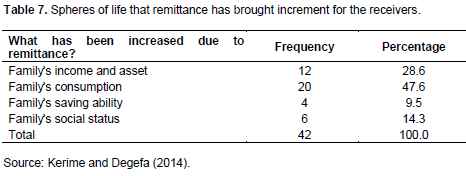

Consumption and asset accumulation/investment cover 47.7 and 52.3% respectively (Table 7). The crucial impact

of remittance at the household level is its contribution in the investment of human capital such as education, health and better nutrition. Remittance is used for whatever purpose (consumption or investment), and it produces positive impact on the economy of a receiving community (Pant, 2008 cited in UN, 2011). Similarly, the household survey result indicated that, remittance have brought an increment in the amount of consumption, income and asset, saving ability, social status and capital of receivers. Thus, remittances have brought about sizeable increment in different spheres of life for the receiving household (Table 7).

Taking into consideration the earlier mentioned economic and other benefits obtained from remittance, 62% of respondents perceive that remittance has improved their livelihood situation through the ways documented. The remaining 38% of remittance receivers assumed that it did not bring a substantial change in the livelihood of their household. According to an elderly non-remittance receiver in Qosero Kebele:

“A family which has a daughter abroad is equivalent to a family which has which lactating cows. The household who has a remitter outside of the country will be benefited from multiple items as a family who has lactating cow is benefited from milk, cheese, butter, yoghurt, etc.” In addition, the family is considered as lucky.

Respondents were asked about the sphere of life that

has been improved due to remittances. They were asked to rank their choices based on order of importance. Responses presented in Table 8 are the primary areas that remittances have brought improvements among others.

The results obtained from one of the remittance receiver case study household head witnesses the change that remittance has brought in the family. Taytu- a 50 years old woman and head of the household made the following point:

“We did not have income source out of agricultural activities. Even the income earned form agriculture is meager. Therefore, the family has agreed to send a family member abroad. We made one of my daughters who were grade 10 to discontinue her education and to migrate in 2011. After three months, she had repaid the initial cost of migration. After a year, she took her younger sister. Currently, the household has better income than in the past days. Now, income obtained from remittance coupled with agricultural activity makes the life of the household by far better than in the past days.”

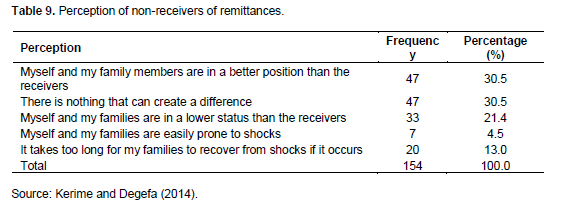

We also investigated how non-remittance receivers perceive the difference that exists between the receivers and non-receivers. There is a difference between these two groups according to the response given by 68% of non-remittance receiver respondents. Some 22% of the sampled non-receivers did not know whether there was a difference between receivers and non-receivers. Some 10% of non-receiver said there was no any difference that could be observed. In addition, non-remittance receiver respondents were given the chance to compare their families with those who have remittances source of income (Table 9). Concerning the sustainability of the impact of remittance, a Development Agent of Paso-mile had put:

“When most people think about the sustainability of remittance, they consider not the sustainability of the impact that it has brought but the flow of remittance itself. Of course, since most migrants are contract workers in the destination country, they will return back within a given time after the end of the contract and the flow of remittance will end. But most impacts of remittance such as the construction of houses, expenditure on health and education, etc are sustainable. These expenditure areas of remittance determine the future destiny of the family.”

According to the Vice Administrator of the Tehuledere Woreda Agricultural and Rural Development, recently the level of poverty and food insecurity in the Woreda is not as serious as what it has been before. Recent migration of females and their remittance flow has its own role in reducing the number of food insecure households in the Woreda. Due to remittance the income of many households had been improved. Receivers had got the chance to construct and repair houses and they had got better capacity to purchase grain for household consumption (Table 10).

Social impact of remittance

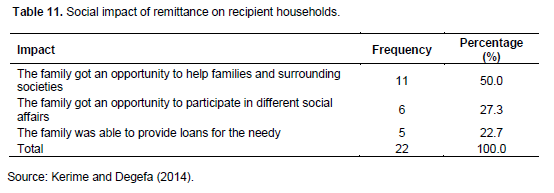

Remittance has lot of social impacts. The migrants are benefiting the community other than their immediate families through remittance as the 39.8% the respondents witnessed. On the other hand, some 34.2% of the respondents indicated that the migrants had not been benefiting other members of the community apart from their own families. The remaining 26% did not know whether migrants are benefiting other members of the community or not. From the total sample of remittance receivers, 28.6% of respondents thought that migrants were benefiting other members of the community. However, 40.5% of respondents replied that remittance is not benefiting member of the community beyond their families. Remittance is improving the receiving house-hold’s relation with families and surrounding societies. Remittance improves family and social relation for 52.4% of remittance receiver respondents but for 47.6% of remittance receivers there is no change in social relation of the family as brought about by remittance (Table 11).

Remittance creates increased social tension within the household both among those at home and within migrants who were remitting to the household (Rodriguez, 2000;

Erhijakpor et al., 2010). Likewise, qualitative results indicated that remittance causes problems sometimes and tension within the family especially on the regulator of the sent money and between the remitter and the family. In some cases even it results into murder incidences among members of the household. A remittance non-receiver case study household in Bededo expresses:

“…I know two sisters by the names Lubaba and Leyla in Kebele 05 who have been migrated after they have married and subsequently both of them have divorced due to remittance related cases.”

Likewise, administrator of Qosero, one of the key informants, indicated that remittance may create social problems as presented in the following case.

“…Remittance sometimes triggered social problems. I know an old man from a Kebele called ‘Weldelulo’ who has been slaughtered by his son as a result of dispute over who should control the money. In some other cases, it is a source of dispute within a family between the husband and wife, adults and the elderly and the husband and the family’s of the remitter if the remitter is married female.”

Remittance reducing vulnerability of receiver households

Remittance tends to increase during economic or social crises and shocks like drought, conflict, crop failure, etc. in the homeland of the migrant. This unique nature of remittance helps the receiving communities to smooth their consumption pattern and stablizes the economy of the recepient households (World Bank, 2005; Ratha and Mohapatra, 2007). Remittance minimizes the vulnerability of households through smoothing consumption patterns (Dugbazah, 2007). The finding of this study also showed similar result.

The fluctuation of remittance with regard to occurrence of shocks was investigated. The result has shown that 43% of receivers were remitted for special occasions and during the occurrence of shocks. But remittance for the remaining 57% of sample remittance receiver households did not increase during shocks and times of problems. Similarly, the amount of remittance had increased during crises and special needs for 36% of remittance receiver respondents. It was not the amount of money that increases during social and economic crises but the frequency of receiving money. However, whether migration increased in absolute term, in its frequency or remain the same, it had reduced the impact of different shocks and crises as underlined by 72% of remittance receiver households. This indeed allows us to conclude that remittance is serving as insurance mechanism for the receivers.

Some 62% of remittance receiver respondents replied that remittance had assisted the receivers to recover from shocks (Table 12). It reduced the fear about future occurrence of shocks and hazards for nearly 45% of remittance receivers. This indicated that, remittance had a role in enhancing the resilience capacity of the receivers together with reducing the fear about the future occurrence of shocks and hazards. Some 13% of respondents had perceived that it takes them too long to recover from shocks while 4.5% of respondents are easily prone to shocks than the receivers (Table 13). This consolidates the fact that remittance has its role in lowering the vulnerability level and increasing the resilience capacity of respondents. The following two case studies clearly compare the living standard of two remittance receiver and non-receiver households found in Qosero.