ABSTRACT

The aim of the paper was to identify the factors that constrain growth of street food enterprises in Ghana. The study achieved this by using panel data from two surveys to estimate the effect of constraints that are self-reported by street food vendors from Kumasi and Tamale metropolises of Ghana on growth of their businesses. Results of the study found inadequate managerial skills and financial constraints to negatively affect the gross margin ratio between the baseline and follow-up periods. In addition, vendors who reported complex regulatory and banking procedure as a constraint experienced a decrease in the rate of growth of their businesses with respect to average daily sales per person. The study recommends that policy interventions aimed at improving the street food sector should aim at addressing managerial constraints or financial constraints or both. Specific policies to address these constraints are presented.

Key words: Constraints, growth, micro and small-scale enterprises (MSEs), street food enterprises, Ghana

Street food vending and street foods

[1] play important roles in the economic development and the lives of most people (especially urban dwellers) in Ghana and other developing countries. Firstly, street foods serve as an important source of affordable and relatively nutritious meal (Otoo et al., 2011; Tomlins et al., 2002). Osei Mensah et al. (2013) in a study on street food consumption in the Kumasi metropolis of Ghana found that it is not limited to low income earners. Street foods also serve as a major source of income and livelihood for a large share of urban dwellers, especially women (Otoo et al., 2011; Narumol, 2006; Jimu, 2004; Tomlins et al., 2002). Tomlins et al. (2002), in a study in Accra-Ghana found street food sector to employ over 60, 000 people and has an estimated annual turnover of over US$ 100 million resulting in profit of about US$ 24 million. Thirdly, the sector also promotes local agribusiness industries by absorbing locally grown and processed crops and raw materials. In this way, raw material producers who ordinarily would have had problems with marketing of their produce have readily available marketing outlets.

On the other hand, street foods may serve as a major source of food-borne diseases and poisoning, with potentially huge health implications to the country (Rheinlander et al., 2008; Mensah et al., 2002). A study by Maxwell et al. (2000) established a positive correlation between consumption of street foods and the prevalence of gastrointestinal infections. Other studies in Ghana have also found street foods as a major source of zoonotic diseases (King, 2000) and heavy metal, residues of pesticides and chemicals used for spraying crops, especially vegetables, on the field (Tomlins, 2002). These food quality and safety concerns have several ramifications on street food enterprises, consumers and expenditure on public health. Vendors who fall sick because they habour some form of enteric bacteria directly lose man-hours and indirectly lose customers if vendors’ absence from business persists. This in turn implies revenue loss to local assemblies.

Despite all the above listed importance of street foods and their ability to serve as a viable engine/tool for economic growth, the street food sector, like many other informal sectors, is constrained by several factors. These factors may include (but not limited to) limited knowledge and skills in business management (Bruhn et al., 2012; Berge et al., 2011; Mano et al., 2011) and inadequate supply of skilled workers (Quader and Abdullah, 2008; Ishengoma and Kappel, 2006; Kayanula and Quartey, 2000).

Other factors include limited access to credit and high cost of borrowing (Martey et al., 2013; Abor and Biekpe, 2006), high cost of production (Martey et al., 2013; Ishengoma and Kappel, 2008; Skinner, 2005), lack of access to legal vending premises (Martey et al., 2013; Bowen et al., 2009), regulatory barriers from city authorities, poor organization and lack of collective action among vendors, etc. These factors either individually or in concert with others work to affect operations of street food enterprises and subsequently performance and growth.

However, little is known about the extent to which these constraints actually hinder the growth of street food enterprises in Ghana. Most constraint studies on SMEs in Ghana (for example, Tomlins et al., 2002; Kayanula and Quartey, 2000) have not linked owners’/managers’ perceived and subjectively reported constraints to growth of these firms. Those that establish this link (for example, Otoo et al., 2012 in Ghana and Ishengoma and Kappel (2008) in Uganda) used owners’/managers’ perception of growth since these studies employed cross-sectional data. It is therefore possible for either highly optimistic or pessimistic assessment by few owners (based on their perception) to skew mean constraints towards a particular direction and subsequently lead to a conclusion that is not really a true representation of the broader picture in that sector.

This study addresses these gaps by first identifying the factors that are perceived by vendors to constrain growth of street food enterprises in Ghana. Following that the study utilizes panel data from two rounds of survey to assess how growth (measured percentage change in gross margin ratio, percentage change in number of customers served and percentage change in average daily sales per person) is significantly limited by identified business constraints. This study is important because knowing which factors really hinder growth of SMEs will inform the choice of appropriate policy measure to address them. It also contributes to the literature on constraints to micro, small and medium scale enterprises (MSMEs) especially in informal sector of the developing countries’ economies.

[1] Following FAO’s definition, this study operationally defines street food as any ready-to-eat food (excluding beverages, as well as semi-processed and unprocessed food items that are used as ingredients in the preparation of other foods) prepared and/or sold by vendors and hawkers, especially in streets and other similar public places. Enterprises included in the study have employee size (excluding the owner) ranging between 1 and 41.

Sampling and data collection process

Multi-stage sampling procedure employing a combination of stratified, simple random, purposive and quota sampling was used to select two hundred and sixty-three (263) street food enterprises were selected from two cities of Ghana, Kumasi and Tamale, due to the large number of urban poor. Apart from the presence of large urban poor, Kumasi and Tamale were selected due to the socio-cultural as well as economic differences between the two cities. While Kumasi is the second largest city, relatively developed and an economically active city throughout the year, Tamale still remains relatively under-developed with high incidence of poverty and perennial migration of some of its active labour force to the South of Ghana, especially during the non-farming season. These differences may affect the type of foods sold, characteristics of street food vendors, business constraints and their effect on performance. These micro-enterprises dealt in four different foods, namely;

‘check-check’[1] (

fried/jollof rice) and

fufu[2] (in Kumasi), waakye[3] and tuo zaafi[4] (in Tamale) based on their predominance in the selected study areas. Stratification was first based on the two cities and subsequently on the selected food types in each city.

Data collection was principally in four phases; stakeholder discussions, reconnaissance survey (with structured interview guide) and baseline and follow-up surveys (using structured questionnaires). Stakeholder discussion with major players was organized during the launch of the Ghana Street Food project. This discussion aimed at identifying the major business-related constraints to street food vending in Ghana and also suggest possible interventions that can help address the constraints that we will identify. Outcome of the stakeholder discussion was analysed, reviewed and subjected to criticisms by panel members and other participant of the project launch. Outcome of these discussions (not reported here due to space) largely informed the design of data collection instrument for reconnaissance survey, especially regarding the business practices and constraints. Key constraints identified by the stakeholder discussions are lack of technical know-how and ignorance on the part of the food vendors, bureaucratic nature of business formalization/registration, lack of business management skills. Others include poor banking and saving culture among vendors, frequent eviction/ejection of vendors from their premises, lack of credit and absence of collection action among vendors due to limited cooperation.

Reconnaissance survey was also conducted using the outcome of the stakeholder discussions as a basis. This process among other things was to obtain information about vendors’ business constraints, vending experience and history, reasons behind the choice street food vending business, employee size, source of business capital and source of business capital. Based on the constraints identified from the stakeholder discussions, reconnaissance survey and review of relevant literature, a research instrument which includes twenty-three (23) MSE constraints was designed and used as the basis for assessing the binding constraints to street food micro-enterprises during the main survey. First round of data collection took place between May and June of 2013 with the follow-up survey taking place between May and June of 2014.

Primary data comprising demographic characteristics of vendors, business characteristics, and business performance measures and vendors’ self-reported business constraints were obtained from owners/managers of sampled street food enterprises. Due to the fact that record keeping was generally not practised by the respondents, it was not possible to capture performance measures from their books. The study therefore used self-reported data obtained directly from vendors, following the recommendation by De Mel et al. (2009) that “simply asking profits provides a more accurate measure of profit than detailed questions on revenues and expenses” to obtained data on sales and profits. These data were compared with those obtained through step-by-step cost revenue analysis and the sales and profit figures in the former process case were found to be more correlated than in the latter where there were a lot of negatives (signifying losses for a typical vending day).

Although, Liedholm and Mead (1999) posit that employee number represents an objective, easy to capture and easy to apply measure of growth, qualitative evidence during field survey reveal that a change in employee number may be less indicative of growth, although we theoretically agree to this assertion. This is because whiles some vendors may intentionally refuse to increase the workforce to deal with operational and cost inefficiencies others prefer to remain legislatively unnoticed, moderate or small. In view of all the aforementioned reasons, the study adopted gross margin ratio, average number of customers served per day and average daily sales per customer (ratio of total sales to number of customers served) as measures of growth and captured data with caution. In order to reduce the variability in performance measures, several measures were taken. Nominal figures from the second round of data collection (follow-up surveys) were adjusted for inflation using the average food consumer price index (CPI) for Ashanti and Northern regions of Ghana over the study period.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics comprising arithmetic means and standard deviations, as well as percentages and frequency tables were used in describing the socio-economic characteristics of street food vendors as well as the characteristics of the vending enterprises in the total sample. For each of the 23 factors that were identified through stakeholder discussions and reconnaissance survey as being possible constraints to business growth, vendors were asked to rank the extent to which they agree to the factors are being constraints to business growth. This ranking was done by using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree and 5 = strongly agree). For the purpose of analysis, these rankings were recoded. Factors with scores above 3 were considered to be constraints and assigned a value of 1 or 0 if the score is 3 or below.

Also, factor analysis was employed to isolate the underlying (common) factors that explain the correlations among the identified potential constraints as well as to determine the extent to which each original constraint depends on each of the common factors. The result of the factor analysis also aimed at grouping the identified potential constraints into related groups so as to reduce the number of dimensions (constraints) that entered the OLS regression models. The scores of the isolated common factors were obtained by computing the average score of the individual original factors that depend on that isolated common factor.

Computation of the three measures of growth was based a typical daily production. The units of analyses presented in Table 1 for the different food types are based on the major ingredient or material used in the production process. Daily estimates were obtained for items or raw materials that were procured and used over several days. The following formulae were used in computing the gross margin ratio and average sales respectively from Table 1:

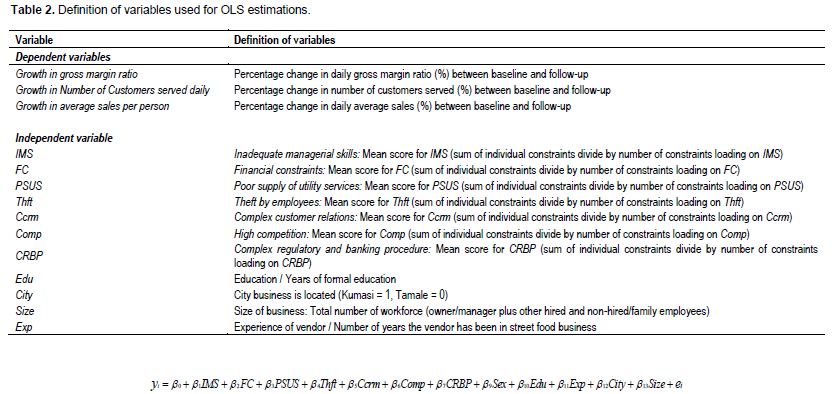

Three separate Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regressions were modelled to estimate the effects business constraints and vendor/business characteristics on each of the measures of firms’ growth (percentage changes in firms’ gross margin ratio, number of customers served daily and average sales), between the baseline and follow-up.

Where yi continuous dependent variables (percentage changes in firms’ gross margin ratio, number of customers served and average sales per customer) explained and defined in Table 2. Also, the definition of business constraints; IMS, FC, PSUS, Thft, LP, Ccrm, Comp, and CRBP as well as vendor and enterprise characteristics are explained in Table 2 where yi represents the error term.

[1] Check-check is a food vending outlet that serves mostly fried rice and jollof rice. Fried rice is prepared by steaming boiled rice, vegetables and spices together. Jollof on the other hand is prepared by boiling rice together with tomato sauce/stew.

[2] Fufu is a staple starchy food prepared by pounding boiled cassava and plantain together in a mortar and pistle, while continuously turning it with the hand. Fufu can also be prepared from boiled cocoyam or yam. Fufu is usually served and eaten with soup.

[3] Waakye is prepared by boiling rice and beans together. It is usually served with a hot sauce, spaghetti, gari and vegetable salad.

[4] Tuo zaafi is a maize or millet dough and cassava dough dumplings prepared and served with green leafy vegetable soup.

Descriptive characteristics of respondents

The found that majority of vendors in the total sample (238 representing 90.49%) were female. In Tamale, all vendors, except one, were females. This corroborates the findings of other studies (Mensah et al., 2002; FAO, 2009; Otoo et al., 2011) which concluded that street food vending is largely dominated by women. An interesting observation is that 23 out of 25 male respondents were in the sale of check-check (fried rice/jollof rice). A typical food vendor is young and married with an average of almost six years of formal education with about 98 (representing 37.3%) having no formal education at all. Also, a typical street food enterprise has a total workforce of 5 (with a range between 1 and 41) and has been in operation for 9 years (with the most experienced vendor being in business for 45 years).

In financial terms, it was found that a typical vendor daily sales revenue of approximately, gross margin of almost GH¢ 83 and a gross margin ratio of almost 18%. The study of found that vendors from Kumasi had higher daily sales revenue and gross margin ((approximately GH¢ 401 (US$ 108) and GH¢ 103 US$ 28) respectively)) relative to vendors from Tamale ((approximately GH¢ 308 US$ 83) and GH¢ 70 US$ 19) respectively)). However, the gross margin ratio of the latter is higher than that of the former. Several factors may account for this. Vendors operating in Tamale may either be more cost effective and hence able to retain more of their sales revenue as profit or the price of food may be higher in Tamale than Kumasi where competition among street food vendors is very high. This latter point is corroborated by the relatively higher average sales per customer in Tamale.

Self-reported constraints to operations of street food enterprises

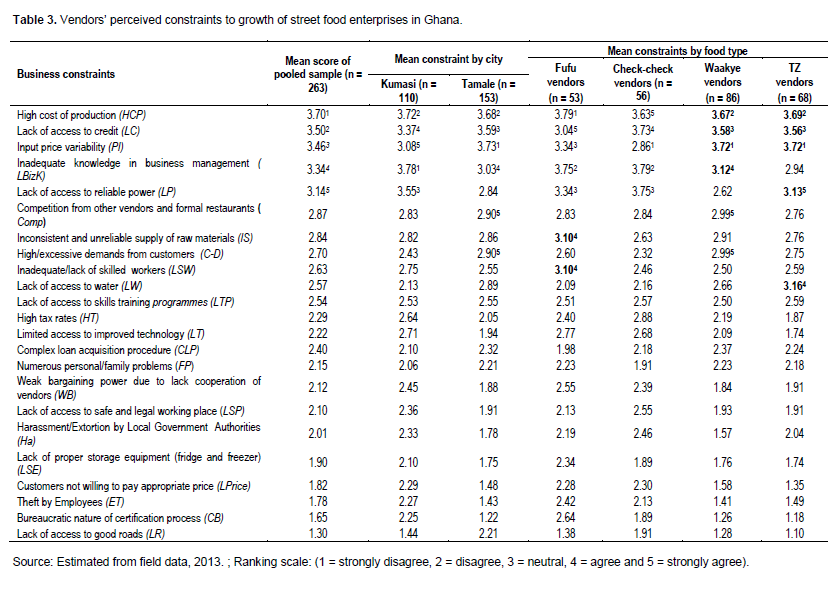

Table 3 presents the mean score for the 23 potential constraints that were identified through literature and the reconnaissance survey.

According to Table 3, only 5 out of the 23 constraints were considered by the pooled sample to be binding to the growth of street food enterprises. High cost of production was ranked (by the pooled sample) as being the most binding of all the constraints with a mean score of 3.70. The high cost of production results from high cost of raw materials and other inputs, and the multiplicity of taxes imposed on vendors. This result is consistent with findings of Martey et al. (2013) in their study of constraints to small scale enterprises in Accra Metropolitan area of Ghana. Similarly, Association of Ghana Industries (AGI) in its report for the 4th quarter of 2012 also found high cost of raw materials as one of the top four constraints militating against the growth of Ghanaian enterprises (AGI, 2012). Lack of access to credit, input price variability, inadequate

knowledge in business management, and lack of access to reliable electricity supply were ranked as the second, third, fourth and fifth most critical constraints respectively. A joint study by US government and Government of Ghana as well as AGI (2012) and Abor and Biekpe (2006) in their study of constraints to Ghanaian firms have both reported limited access to credit as constraining the growth SMEs in Ghana.

The result on input price variability is consistent with earlier works by (Martey et al., 2013; Quader and Abdullah, 2008; Skinner, 2005). Input price variability makes planning of business operations difficult. A picture reflective of this concern is captured in the following complaint by a waakye vendor from Tamale: “you are no longer sure of which figures to put on your budget for input purchase when going to the market. They keep increasing the prices of raw materials almost every day. It makes it even difficult for us to plan and even price our food appropriately”.

Lack/limited access to reliable electricity power for business operations was considered the fourth most binding constraint. This is especially so for check-check vendors whose peak business time is at night. Most respondents who vend at night indicated that poor supply of power by the national grid has a negative impact on their customer base as well their own security. Other vendors who aimed at maintaining their customer base through the provision of alternative power sources such as generators, rechargeable lamps did so at an extra cost arising from purchase of power generators and cost of fuelling.

Beyond these five constraints which were unanimously agreed by all categories of vendors to be binding, inconsistent and unreliable supply of raw materials, inadequate/lack of skilled workers also had mean constraint indices beyond 3 for fufu whilst the index for lack of access to water was also binding for vendors of tuo zaafi.

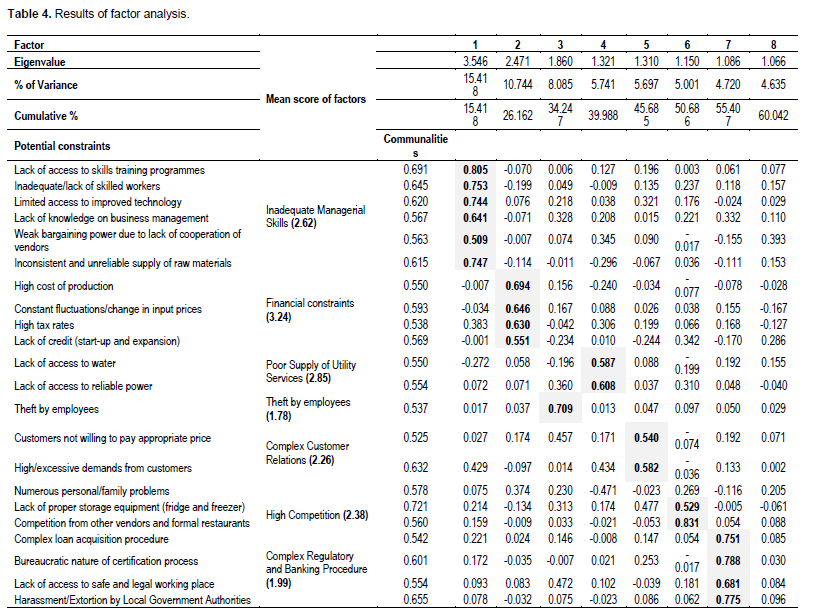

Results of factor analysis

In order to be certain that factor analysis is an appropriate tool for handling the data from a sample of 263 owners/managers of street food enterprises, the Kaiser-Mayer Olkin (KMO) test was used to determine the extent to which the variation in the constraints are explained by the common factors. The communality of the performance index ranges between 0 (indicating that the common factors explain none of the variance) and 1 (indicating all the variance is explained by the common factors). Generally, a KMO score of between 0.5 and 1.0 is considered acceptable (Malhotra, 2007). Thus, a KMO value of 0.744 is a good indication of sample adequacy and a confirmation of the appropriateness of factor analysis. Also, the communalities for the potential constraints ranged between 0.525 and 0.721 with an

average of 0.60. This implies that on the average 60% of the variation in each constraint can be explained by the common factors.

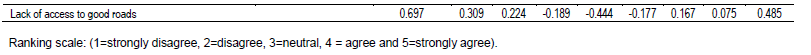

Using a promax oblique method of rotation, the factor loadings in Table 4 were obtained. According to Quarder and Abdullah (2008), promax rotation allows correlation among the factors thus helping to achieve a simple and realistic structure. According to the results of the rotation, factor 1 has high and positive loadings for constraints such as lack of access to skills training programmes, inadequate/lack of skilled workers, limited access to improved technology, lack of knowledge on business management, inconsistent and unreliable supply of raw materials and weak bargaining power due to lack of cooperation of vendors. All these constraints are related to limited competence of owners/managers and employees to make good decisions based on sound managerial principles. Factor 1 is therefore labelled ‘inadequate managerial skills'.

High cost of production, constant fluctuations/change in input prices, lack of credit (start-up and expansion), and high tax rates loaded high on factor 2. Factor 2 is therefore labelled ‘financial constraints'. Again, these findings are consistent with the outcome of binding constraints identified above and other studies like Martey et al. (2013) and Abor and Biekpe (2006) that focused on constraints to SME growth in Ghana. These constraints increase the cost of business operations, affect the planning process of these vendors and subsequently reduce the profit of these enterprises. Factor 3 loaded high on only one constraint, theft by employees. Factor 3 is therefore labelled same. Interactions with owners/managers of street food enterprises revealed that a major problem they face is theft and diversion of money and other resources by their workers.

Factor 4 on the other hand has high positive loadings/correlation on/with lack of access to water and lack of access to reliable power (electricity). These two constraints greatly affect the smooth operations of the businesses of vendors and assurance of food safety. In cases where vendors experience acute shortage in the supply of water, observing the required hygiene is compromised in an attempt to economize the limited water available. Unreliable power (electricity) affects night operations of vendors. Factor 4 is captioned ‘poor supply of utility services’. Customers not willing to pay appropriate price, and high/excessive demands from customers also loaded high on factor 5. The factor is accordingly labelled ‘complex customer relations'. Most vendors assert they have difficulties passing on the high cost of production to consumers/customers since doing so will lead to loss of customers. Competition from other street food vendors and formal restaurants as well as lack of storage equipment such as fridge and freezers were also considered important constraints and loaded high on factor 6 (high competition and lack of storage equipment). Bureaucratic nature of (health) certification process, lack of access to safe and legal working place, and harassment/extortion by local government authorities have high loadings on factor 7. The seventh factor is therefore named ‘complex regulatory/banking system’. Factor 8 has low loadings on all the constraints and can therefore be concluded as not explaining any of the constraints.

Based on the results of the factor analysis, the seven isolated common factors were used as explanatory variable in the three OLS regressions in Table 5. Estimation of effects of business constraints on growth.

Table 5 reports results of OLS regression to estimate whether identified constraints limit growth of street food enterprises. It shows the coefficients (βi) and the standard errors of each of the three indicators of firm growth; percentage change in gross margin ratio, percentage change in number of customers served daily and percentage change in average sales per customer.

In terms of the effect of business constraints on growth of gross margin ratio and average daily sales per customer, the study’s hypotheses on inadequate managerial skills and financial constraints were both confirmed as shown in Table 5. Street food vendors who reported experiencing constraints related to managerial inadequacies such as lack of skilled workers, lack of knowledge in business management and unreliable supply of raw materials experienced a reduction in growth rate (in terms of gross margin ratio) of about 6.8 and 6.6% points respectively between the baseline and follow-up periods.

This result is consistent with other studies that found lack of managerial capital as a critical constraint to performance and growth of SMEs. For instance, a study by Bruhn et al. (2012) among SMEs in Mexico found out that human capital had a first order effect on firm performance and that addressing this limitation positively impacted the sales and profit by 80 and 120% respectively. Similarly, Mano et al. (2011) found basic skills in business management to be critical to small entrepreneurs operating in an industrial cluster of Suame Magazine in Ghana. In addition, managers with less experience have their enterprises facing difficulties with solvency and may also experience higher expenditure to revenue ratio (Hall, 2000) due to less efficient combination of production resources. These, in the long run, affect the firm’s ability to remain profitable and viable.

With regards to effects of financial constraints on growth of firms, column 2 of Table 5 shows that reporting financial related constraints at baseline limited the growth of firms’ gross margin ratio and average daily sales per customer by about 6.2 and 7.3% points respectively during the follow-up period at a 10% significance level. Some earlier studies in Ghana have also found financial-related constraints as limiting the performance of micro, small and medium scale firms. For instance, Martey et al. (2013) in their study of constraints to performance of small scale enterprises in the Accra-Ghana reported limited access to credit, high cost of borrowing and unstable input prices as critical factors militating against the performance of the sector. Other studies such as (AGI, 2012; Abor and Biekpe, 2006) have both reported findings that corroborate the negative effect of financial constraints on frim performance in Ghana. These factors either individually or in concert with others affect operational and expansionary activities of the business. For instance, limited access to credit may affect the firm’s ability to undertake long-term investment in the business, whereas high input price variability makes business planning, costing and pricing difficult. These in turn may affect the firm’s ability to generate more sales as well as attract premium customers who will be willing to pay premium prices.

The study also found that vendors operating in Kumasi experienced a significant reduction in the growth of their customer base as well as the daily sales per person. Also, employing an additional person in the business decreases the daily number of customers served by about 5.1%.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Analysis of business constraints based on vendors’ self-reported perceived constraints to business growth found high cost of production, lack of access to credit, input price variability, inadequate knowledge in business management, and limited access to electricity power as five top constraints in the pooled sample. These rankings were similar across the two study areas and the type of food sold. Grouping the 23 identified potential constraints based on the degree of commonality resulted in 7 different factors with inadequate managerial skills and financial constraints ranking first and second most critical constraints respectively. Results of OLS estimation of the effects of constraints on business growth found inadequate managerial skills and financial constraints to negatively affect the gross margin ratio between the baseline and follow-up periods. In addition, vendors who reported complex regulatory and banking procedure as a constraint experience a decrease in the rate of growth of their businesses with respect to average daily sales per person.

Based on the self-reported constraints to growth of street food enterprises in Ghana and econometric analysis of constraints to growth, the study concluded that policy interventions aimed at improving the street food sector should aim at addressing managerial constraints or financial constraints or both. Specific interventions may include period training business management, group formation and management as well as training on requirements for credit acquisition. In order to deal with problems of high cost of production and input price variability, vendors should be encouraged to consider bulk procurement of raw materials that are less perishable. Other measures to deal with these problems may include entering into agreements with trusted suppliers so that payment of items may be procured on credit or price negotiated to control the level of variability. Future studies may consider increasing the sample size for a specific food and also track results over a longer period of time.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Association of Ghana Industries (AGI) (2012). The AGI business barometer: 4th quarter 2012.

|

|

|

|

Berge LIO, Bjorvatn K, Tungodden B (2011). Human and Financial Capital for Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field and Lab Experiment. NHH Dept. of Economics Discussion Paper No. 1/2011.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bruhn M, Karlan D, Schoar A (2012). The impact of consulting services on small and medium enterprises: evidence from a randomized trial in Mexico. Yale Economics Department Working Paper No. 100.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

De Mel S, McKenzie DJ, Woodruff C (2009). Measuring microenterprise profits: Must we ask how the sausage is made? J Dev. Econ., 88: 19–31

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2009). Good hygienic practices in the preparation and sale of street foods in Africa. Tools for training. Rome.

View Accessed: December 2nd, 2013]

|

|

|

|

|

Ishengoma EK, Kappel R (2006). Economic growth and poverty: does formalisation of informal enterprises matter? GIGA Working Papers No. 20.

|

|

|

|

|

Ishengoma EK, Kappel R (2008). Business Constraints and Growth Potential of Micro and Small Manufacturing Enterprises in Uganda. German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA) Working Paper No 78. Hamburg.

|

|

|

|

|

Jimu IM (2004). An exploration of street vending's contribution towards Botswana's vision of prosperity for all by 2016. J. Afri. Stud., 18(1): 19-30.

|

|

|

|

|

Kayanula D, Quartey P (2000). The policy environment for promoting small and medium enterprises in Ghana and Malawi. IDPM (University of Manchester) Finance and Development Working Paper No. 15.

|

|

|

|

|

King LK, Awumbila B, Canacoo EA, Ofosu-Amaah S (2000) An assessment of the safety of street foods in the Ga district, of Ghana; implications for the spread of zoonoses'. Acta Trop. 76:39-43.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Liedholm C, Mead CD (1999). Small Enterprises and Economic Development, The Dynamics of micro and small enterprises, Rutledge Studies in Development Economics, New York.

|

|

|

|

|

Mano Y, Iddrisu A, Yoshino Y, Sonobe T (2011). How can micro and small enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa become more productive? The impacts of experimental basic managerial training. World Dev. 40(3):458-468.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Maxwell D, Levin CE, Armar-Klemesu M, Ruel MT, Morris SS, Ahideke C. (2000). Urban Livelihoods and Food and Nutrition Security in Greater Accra, Ghana. International Food Policy Research Institute, Report 112, April.

|

|

|

|

|

Mensah P, Yeboah-Manu D, Owusu-Darko K, Ablordey A (2002). Street foods in Accra, Ghana: how safe are they? Bull WHO 80(7): 546-554.

|

|

|

|

|

Narumol N (2006). Fighting Poverty from the Street: A survey of Street Food Vendors in Bangkok. Thailand Series No 1.

|

|

|

|

|

Osei Mensah J, Aidoo R, Appiah NT (2013). Analysis of street food consumption across various income groups in the Kumasi metropolis of Ghana. Int. Rev. Manage. Bus. Res. 2(4):951-961.

|

|

|

|

|

Otoo M, Fulton J, Ibro G, Lowenberg-Deboer J (2011). Women entrepreneurship in West Africa: the cowpea street food sector in Niger and Ghana. J. Dev. Entrepr. 16(1):37-63.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Quader SM, Abdullah MN (2008). Constraints to SMEs: a rotated factor analysis approach. South Asian Stud. 2(24):334-350.

|

|

|

|

|

Rheinlander T, Olsen M, Bakang JA, Takyi H, Konradsen F, Samuelsson H (2008). Keeping up appearances: perceptions of street food safety in urban Kumasi. J. Urban Health: Bull. New York Acad. Med. 85:6952-964.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Skinner C (2005). Constraints to Growth and Employment in Durban: Evidence from the Informal Economy. Research Report No. 65, School of Development Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban.

|

|

|

|

|

Tomlins KI, Johnson PN, Obeng-Aseidu P, Myhara B, Greenhalgh P (2002). Enhancing product quality: street food in Ghana: a source of income, but not without its hazards. PhAction News P 5.

|

|