ABSTRACT

One of the most important facets of off-farm activities is providing employment opportunities and additional income for rural households and thereby accommodates the seasonal and fluctuating agricultural production. Given this, identifying the underlying determinants of off-farm participation and its impact on crop yield was found to be of the essence. Cross sectional data was collected through structured questionnaire administered on 384 randomly selected farmers. Descriptive statistics, probit and Ordinary Least Square (OLS) models as well as t and chi-square tests were used to analyze the data. The regression result revealed that off-farm participation was positively influenced by gender, education, working people, number of pack animals and credit access; while age and land size carried a negative sign. Off-farm participation was also found to have a negative and statistically significant impact on crop yield where non-participants were better producers; since majority of off-farm participants participate only on food-for-work which has nothing to add for crop yield rather than compromising farm activities. Hence, training on non-farm activities need to be given; the current adult education, being propagating, need to be strengthened; and there is a need to solve liquidity problem through credit access that could serve as startup capital.

Key words: Off-farm, participation, smallholder farmers, probit, Ordinary Least Square (OLS).

As engine of economic growth and poverty reduction, in developing countries, agriculture should be integrated with sectors that have direct or indirect linkages. According to Babatunde et al. (2010) financial capital appears to be the most limiting factor for farming, so that cash income from off-farm activities helps to expand farm production; increase household income and reduce risk of crop failure. Hence, off-farm is one among the activities whereby agriculture is believed to be integrated with. World Bank (2008) has reported that, in most developing countries, the importance of off-farm activities is increasing and estimated to account for 30 to 50% of rural incomes. According to Rios et al. (2008), the higher the off-farm income is, the larger capital endowments will be; and having higher capital endowments will in turn help to produce more and more and even to be productive. According to Asenso-Okyere and Samson (2012), Haggblade et al. (2010) and Diao and Nin Pratt (2007), modern agricultural inputs can result with ample production and productivity of marketable commodities that results with trade linkage; the requirement of agricultural inputs and marketing facilities by itself, then, induces off-farm activities.

As per the view of Haggblade et al. (2010), those who live in arid areas where production is sluggish tend to participate in off-farm activities and diversify their income sources. Similarly, in Burkina Faso, Zahonogo (2011) purport that a decline in farm income and farm production let farmers to participate in off-farm activities; and increment in farm production and income do the opposite. Furthermore, in areas where agriculture is grown, the rural off-farm economy was also been founded to be grown (Haggblade et al., 2009). While quantifying this direct linkage between agricultural growth and off-farm economy, Haggblade et al. (2009) reported that a one dollar value invested on to agriculture generates 0.3 and 0.5 additional dollar on to rural off-farm income in Africa and Latin America, respectively.

In Africa, off-farm economic activities, as a means of income diversification, are very much indispensable for improving the livelihood of rural poor (Asenso-Okyere and Samson, 2012; Diao and Nin Pratt, 2007). Besides, it can serve as source of input supply for agricultural production and employment opportunity for those who do not have arable land and do not further want to rely on agriculture. Despite its vitality, in Africa, off-farm activities participation is low; and according to Haggblade et al. (2007), 37% of the rural households’ income is really extracted from off-farm activities where surprisingly not more than 20% of the labor force is being participated. Likewise, in Nigeria, a study by Adewunmi et al. (2011) revealed that participation in off-farm activities more particularly wage employments of skilled and unskilled had resulted in a reduction of rural poverty by 11.02 and 10.68%, respectively; participants lessen poverty better than non-participants (Alaba and Kayode, 2011).

In Ethiopia, being part of developing regions in general and sub-Saharan Africa in particular, agriculture is the real backbone that enables 85% of Ethiopian people to walk upright and be able to feed the remaining 15% of the fortune coincidence urban residents. In line with this, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (2010) acclaimed smallholder farmers in producing majority of the country’s total production. Furthermore, World Bank (2010) inferred that 90% of the foreign earnings and 70% of the raw materials for industry are being sourced from agriculture. Hence, 85% of the Ethiopian people believe that agriculture is the way out to be food secured and even be luxuriant in the long run. Given this deep rooted belief, starting from recent past, arable land size and agricultural production are dwindling and thereby the society is being forced either switching to off-farm activities or stretch their hand for food aid basically for

clothing the food longing mouths at home.

According to Merima and Peerlings (2012) and Abebe (2008), in Ethiopia, farmers tend to participate in off-farm activities to satisfy consumption needs by supplementing the sluggish agricultural income caused by erratic and seasonal rain fall; and due to crop failure and the resultant abundant labor force. Besides, farmers are vulnerable both for natural and manmade disasters and shocks that could be weather related, pests, death of livestock and others. As a means of relief, rural farm households prefer to participate in off-farm activities and diversify their income thereby (Berg and Kumbi, 2006; Dercon and Woldehanna, 2005). Hence, a certain farm household is tempted to participate in off-farm activities due largely to push factors, like drought. They further inferred that, Ethiopian rural poor prefer to participate in off-farm activities that require less entry costs like fire wood collection and charcoal production, while the most lucrative off-farm activities are left for the haves. Contrary to this, some rural farm households tend to participate in off-farm activities basically to widen their income sources given their ample agricultural production and the resultant accumulated wealth, as a pull factor.

In line with the above inclination, Rijkers et al. (2002) as cited in Woinshet (2010) purported that 25% of Ethiopian rural households own more than one labor intensive off-farm activities, although 23% of these rural households did their off-farm activities parallel with their agricultural practices. Hence, only 2% of Ethiopian rural households were those who exclusively rely on off-farm activities. Besides, according to Merima and Peerlings (2012) for the past eight years, back from 2012, not more than 25% of the rural households had engaged in off-farm activities which are minimal compared with 42% of the sub-Saharan Africa average; and its contribution for employment creation in Ethiopia is 1.14%. From this one can deduce that Ethiopian rural households’ off-farm participation is insignificant and its effect onto crop production as well as its overall benefit has not yet been exploited. Hence, identifying determinants of off-farm participation decision and examining the impact of participation on crop yield is found to be imperative for a clear and sound policy indication whereby farm households would participate and diversify their income and cope up food security challenges.

Site selection, sampling method and data collection

As far as the study area selection was concerned, compared with the rest districts of Southern zone, Raya-Azobo and Raya-Alamata are more of promising and lucrative with plenty resource reservations basically fertile land resource, ground water, flat plain land supported by runoff rain water from the surrounding hilly parts. Despite these endowments, since production is decreasing, these districts were reported to face recurrent drought and food insecurity; and the society is been engaged in off-farm activities basically tocurtail the food shortage. As a result of this researchers were intended to have a look on the impact of off-farm activities participation on crop yield.

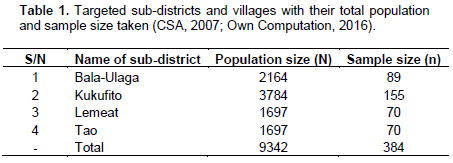

Multi-stage sampling procedure was followed to reach on to final respondents. Firstly, Raya-Azebo and Raya-Alamata districts were selected from Southern Tigray; followed by the randomly selected four sub-districts, Bala-Ulaga, Kukufito, Lemeat and Tao. Thirdly, on the basis of Yamanes’ sample size determination formula, as cited in Israel (1992), 384 sample respondents were calculated. Finally, 384 respondents were randomly selected from the list provided from each sub-district, as its proportion is shown in Table 1 and these people were considered to collect primary data mainly through structured questionnaire in 2014 cropping year. In-depth interview with crop production personnel and farmers who were on the verge to leave agriculture were interviewed. Besides, four focus group discussions with off-farm participants and non-participants, including female participants, were held to support the questionnaire based data. Interviewees and focus group discussants were selected purposively with the assumption that these people could provide us with tangible and pertinent information in the ground.

Method of data analysis and econometric model specification

To analyze the data, descriptive statistics like mean, percentage and standard deviations were used to assess socio-economic and demographic characteristics of sample respondents; while probit model was used to examine determinants of participation, Ordinary Least Square (OLS) model was employed to examine the impact of participation on crop yield. Besides, to test the relationship between dependent and independent variables vis-à-vis the two groups of individuals, t-test and Chi-square tests were used, respectively, for continuous and dummy variables. Data collected through interview and focus group discussion was basically analyzed qualitatively.

Regardless of the amount of money earned and the duration farmers relied on off-farm activity, in this article, a farmer was taken as off-farm participant if he/she did out of his/her farm land; while those who solely dependent on their farm land were considered as non-participants. Due to this dichotomous classification, the dependent variable (off-farm participation) has a binary nature taking the value of “1” for participants and “0” for non-participants that paved the way to employ binary outcome models particularly probit model. The reason behind employing probit model was due to its normal distribution assumption of error terms and farmers’ unobserved or latent behavior by which households are assumed to make decisions pertaining to utility maximization; and hence in this model there is a latent or unobservable variable that takes all the values in (-∞, +∞). As a result, probit model can be expressed by the following general formula:

Pr (Y=1/Xi) = Φ (β1 X1 +εi1) (1)

The latent variable Yi* is not observable and is represented by its proxy Yi taking a value one (1) for participants and zero (0) for non-

participants.

Y*i = X’i β +εi (2)

where ε | x is a normally distributed error term.

Thus, for the household i, probability of participation is given by:

P(1) = Φ (βXi) (3)

where P (1) is the probability of participation, Φ is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution, β is the parameters that are estimated by maximum likelihood, x′ is a vector of exogenous variables which explains off-farm participation. Therefore,

OFP=Φ(β1GENDER+β2AGE+β3EDUC+β4WORKING+β5DEPENDENT+β6LANDSZ+β7MRKTDIS+β8LOCATION+β9TLU+β10PACKANIM+β11CREDIT (4)

Besides, to estimate magnitude of parameters or variables mainly to clearly put the percentage likelihood of participation, marginal effect of variables was calculated. Marginal effect of a variable is the effect of unit change of that variable on the likelihood of participation and it can be seen as P(Y = 1|X = x), given that all other variables are constant. Hence, it is expressed as:

As far as examining the impact of participation on crop yield was concerned, Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression model was employed due to the continuous nature of the dependent variable, crop yield measured in quintal. Furthermore, according to Gujarati (2006), with the assumption of classical linear model, OLS estimators are with unbiased linear estimators with minimum variance and hence they are Best Linear Unbiased Estimators. Hence, its specification is given as follows using the same independent variables used in probit model earlier.

Y = β0 + βi Xi +U

where Y is the dependent variable (crop yield), Xi is a vector of explanatory variables, βi is a vector of estimated coefficient of the explanatory variables (parameters) and ui indicates disturbance term which is assumed to satisfy all OLS assumptions (Gujarati, 2006).

Cropyld=β0+β1GENDER+β2AGE+β3EDUC+β4WORKING+β5DEPENDENT+β6LANDSZ+β7MRKTDIS+β8LOCATION+β9TLU+β10PACKANIM+β11CREDIT (6)

where Cropyld=Continuous dependent variable indicating crop yield measured in quintal.

Therefore, description of variables indicated earlier and their expected sign or hypothesis has shortly been summarized in Table 2.

Socio-economic and demographic characteristics of sample households

Examining farm households’ socio-economic and demo-graphic characteristics is believed to be an important indicator for probability of off-farm participation in such a way that farm households can be determined with. As a result of this, an attempt has been made to describe some socio-economic and demographic characteristics where differences between participants and non-participants were tested using t and Chi-square tests.

Table 3 clearly purports that majority of the sample respondents (73.44%) were off-farm participants. In line with this rate of participation, majority of participants (78%) were male headed households supported with a significant Chi-square test result. Compared with non-participants, participants were male headed households, younger in age, educationally better, large in number of working people, wealthier in pack animals possessed and farm income and then with better credit access. On the other hand, non-participants were owners of large arable land size and better crop producers. These all differences were supported with significant t and Chi-square tests for continuous and dummy variables, respectively.

Types of off-farm activities vis-à-vis place of work

Types of off-farm activities along with place of work were discussed in Table 4.

As it can be seen in Table 4, 65.6% of the total off-farm participants were engaged in food-for-work under the umbrella of Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP). These people were paid employees where one person was expected to do five days per month and will be awarded birr 19 in cash and 3 kg (0.03 quintal) in food/kind. As far as place of work was concerned, 76.95% of off-farm participants have been doing with in their respective sub-districts. To engage in food-for-work and transacting goat, sheep and cereals by buying and selling on market day time mainly on weekly and monthly basis, farmers were not forced to go out of their residence and thereby lose their social tie and family kinship.

Table 4 further reveal that, 67.02% of the total participants were instigated to participate due to the advent of and access to PSNP; followed by their residences’ proximity to urban area that is believed to expose them to new and updated information as well as market identification mainly for petty trading activities like trading egg, coffee, honey, selling local beer (ale) and using cart.

Table 4 also indicated that, more than 57.84% of non- participants were seriously inhibited by absence and the resultant farness of off-farm opportunities coupled with shortage of startup capital. Had there been off-farm opportunities, they would not have been exploited opportunities due largely to shortage of startup capital. From this one can infer that, farm respondents were highly intended to do activities that requires startup capital like trading camel-the then costly animal being transacted and trading cereals across different regions. On the other hand, opportunities’ farness highlights that, respondents were intended to do off-farm activities without compromising their farm activities, their family’s love, affection and social ties.

Estimation results of probit regression model

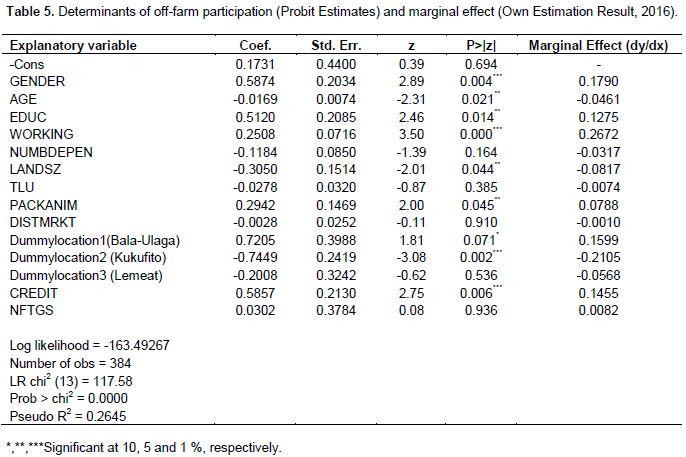

Before rushing to regression result display, pair-wise correlation matrix and the Brush Pagan test were used to test the problem of multicollinearity and hetroscedasticity, respectively (Table 5).

Implication of gender on participation decision is positive and statistically significant at 1% level. Male headed households, citrus paribus, have 17.9% higher probability of participation than female headed households who are more probable to be sandwiched with child rearing practices. In fact, in the study districts, letting females to be a household head is not yet well developed and recognized. Consequently, female headed households mostly are those who are widowed and divorced; and hence, challenged by districts’ labor division culture. In line with this, the prior proposed hypothesis is not rejected at 1% significance level. The finding corroborates with the findings of Haggblade et al. (2010) in North Africa, Latin America and West Asia; Babatunde and Qaim (2009) in Kwara State of Nigeria and Abebe (2008) in Ethiopia where by female-headed households are less probable to participate and influenced by cultural influences. However, it strongly disagrees with the findings of Merima and Peerlings (2012) in Tigray, Amhara, Oromia and Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples regions of Ethiopia; Alaba and Kayode (2011) in South West Zone of Nigeria; and Kaija (2007) in rural parts of Uganda where female-headed households were better off-farm participants unlike male headed households.

Effect of age on participation is negative and statistically significant at 5% level that lets not to reject the prior proposed hypothesis. By its very nature, off-farm participation does require physical strength and fitness whereby younger farmers are better than older ones. Keeping other things constant, as age increases by a year, probability of participation would decrease by 4.61%. Old aged farmers really have an accumulated farm experience like plot preparation and in clearly identifying what and when to sow crops. Besides, they are too stable and mostly could not think some other off-farm activities and migration. Due to this, they are more probable to invest their time on farm activities that participating in off-farm activities.

Contrary to old aged farmers, younger farmers are improbable to be stable and be motivated to do their farm activities. They really wonder here and there in search of some lucrative off-farm activities. Typically, inter and intra migrations were their features and hence they engage in farm activities consciously to buy time. The finding is consistent with the findings of Babatunde and Qaim (2009) in Kwara State of Nigeria and Abebe (2008) in Ethiopia; and Kaija (2007) in Uganda in such a way that probability of participation decreases as age increases. Nevertheless, the finding contradicts with the finding of Zahonogo (2011) in Burkina Faso and Berg and Kumbi (2006) in Ethiopia where older farmers tend to participate better than middle or younger farmers.

The probit estimation result also reveals that, the effect of education (literate and illiterate) is positive and statistically significant at 1% level. In fact, majority of the sample households have engaged in food-for-work, as their typical and best off-farm activity. Food-for-work, therefore, did not require education and for that pointing finger signature is enough basically to take the salary either in cash or in food. Despite this, the implication here is that, the more farmers become literate the higher will be their probability of searching off-farm work in non-agricultural sectors. Magnitude of the positive sign suggests that literate households, keeping other things constant, have 12.75% higher probability of participation unlike their counter parts. The finding confirms the findings of Zhu and Luo (2006) cited in Babatunde and Qaim (2009) in such a way that the more literate the household is, the more probable to search and participate in profitable off-farm activities. Hence, the prior hypothesized positive coefficient is accepted at 1% level of significance.

Off-farm participation decision is positively related with number of working people or active labor force at home; and statistically significant at 1% level. Presence of larger number of working people in a certain house can really do and manage both farm and off-farm activities without compromising each of the activities. A unit increase in number of working people, citrus paribus, would raise the probability of off-farm participation decision by 26.7%. From this inference can be made that households with large active labor force would more be probable to participate in such a way that labor division would prevail more; and besides, enough labor force at home would let family members to participate in off-farm activities. The finding is consistent with the findings of Zahonogo (2011) in Burkina Faso. As a result of this, the prior indeterminate hypothesis is liable to be positive and statistically significant at 1% level.

The regression result indicated that, the effect of land size on off-farm participation decision is negative and statistically significant at 5% level of significance. As land size increases by one Tsimad, keeping other things constant, the probability of participation would decrease by 8.17%. In the study districts, households who owned an arable land size ranged in between 1 and 2 Tsimad are young farmers while the larger land share was positioned on modal age group interval of 40 to 56 years and the preceding age group interval of 57 to 73 since they have had a great share from the last regional land redistribution held twenty five years back.

Young age groups, therefore, are more liable to meager land size transfer from their fathers’ and mothers’ lottery, a single dead bodies and if possible, expanding to the frontier. In the study region, Tigray, for instance, 4,005 hectare was given for 15,198 youngsters through inheritance; and 27,924 hectare was divided among 23.6 thousand youngsters in the frontiers (Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development (BoARD), 2011). It is possible, therefore, to deduce that when we come across higher age groups, it is fortunate to find higher land holding size. This large land holding size is found to be imperative for producing a relatively higher crop production that would retain them to do farm activities and not to participate in off-farm activities. Hence, it is possible to infer that, participation in off-farm activities was in response to farm land constraints. The finding is in line with the findings of Asenso-Okyere and Samson (2012) in Africa at large; Alaba and Kayode (2011) in South West Zone of Nigeria; Babatunde and Qaim (2009) in Kwara State of Nigeria and Abebe (2008) in Ethiopia. The prior hypothesized positive coefficient is rejected at 5% level of significance.

Presence of pack animals has positive relationship with participation and statistically significant at 5% significance level. The finding reveals that a unit increase in draft animals would raise the probability of participation by 7.88%. Farm households who possess pack animals are more probable to participate in activities like trading cereals, doing with cart, transporting sand and stone for construction purpose, charcoal production, fire wood selling and the like. This finding is similar with the findings of Abebe (2008) and Berg and Kumbi (2006) in Ethiopia as if households who possess pack animals would participate better than those who did not possess. Nonetheless, the finding strongly contradicts with the finding of Rios et al. (2008) whereby pack animals would transport manure from home to farm land and thereby increase crop production that finally decreases the probability of off-farm participation decision. The prior hypothesized positive coefficient is accepted at 5% significance level.

As a liquidity factor, access to credit is one best option whereby smallholder farmers could be instigated in diversifying their economic base. Access to credit has a positive effect on participation and statistically significant at 5% level of significance. In line with this, credit non-rationed farm households, keeping other things constant, have 14.55% higher probability of participation unlike credit rationed farmers. Hence, access to credit and taking credit influences participation, indicating that the more farmers have access to source of finance, the more likely to decide and participate in off-farm activities. The finding agrees with the findings of Adebiyi and Okunlola (2013) in Oyo State of Nigeria and Abebe (2008) in Ethiopia; as if taking credit is imperative for solving liquidity problem and thereby increases the probability of participation. On the other hand, the finding contradicts with the findings of Babatunde and Qaim (2009) in Kwara State of Nigeria where liquidity problems, while intending to participate in off-farm activities, could not be solved by accessing and taking credit. The prior proposed positive coefficient is not rejected at 5% level of significance.

Location can serve as a proxy of rain fall availability, productive potential of districts, sub-districts and villages; and it is worth to note discrepancy of participation among sub-districts. Consequently, sub-district dummies have been created; Tao was taken as a reference group due to its middle crop production position. Relative to Tao, theprobability of participation is higher in Balla-Ulaga sub-district by 15.99%; a sub-district basically with higher crop yield and total farm income and it is statistically significant at 10% level of significance. Compared with Tao, the probability of participation is much lesser in Kukufito sub-district by 21.05% that relatively is food-deficit and a sub-district typically credit rationed due to rules of their holly Qur’an and it is statistically significant at 1% level. Farmers with relatively better crop yield and total farm income, therefore, tend to participate in lucrative off-farm activities unlike farmers with low crop yield and farm income. Due to this, the finding completely disagrees with the findings of Zahonogo (2011) in Sudanese, Sahelian, North and South-Guinean zones of Burkina Faso and Abebe (2008) who found as participation is higher and lower in food-deficit and surplus regions, respectively.

It is believed that providing non-farm training is imperative for instigating farmers to participate and thereby diversifying their economic and income base. Although, the probit estimation result is not statistically significant, non-farm training has a positive linkage with off-farm participation decision where it gives an insight to provide and strengthen trainings pertaining to off-farm activities. In the study districts, there is a cross generational task of preparing cultural manifestation using animal skin as well as a culture of weaving (to prepare cultural dresses). Hence, there is a need to invigorate this cross generational endowment via providing an inclusive training pertaining to the aforementioned focus areas.

Impact of off-farm participation on crop yield

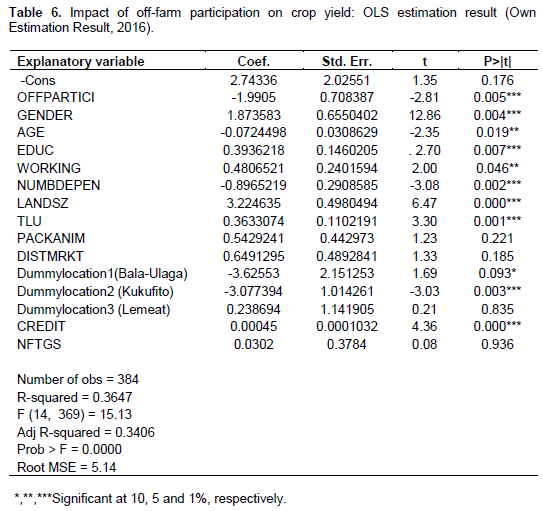

Table 6 depicts the impact of off-farm participation on crop yield considering Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression model as a measuring instrument.

As it has already been discussed earlier, the t-test statistics result inferred that yield difference between off-farm participant and non-participant is significant where non-participants produce better than participants. Consistent with the descriptive statistics, regression result revealed that off-farm participation has a negative and statistically significant impact on crop yield, at 1% level of significance. Hence, both descriptive and econometric statistics results purport the negative impact of off-farm participation on crop yield. The regression result shows that, keeping other things constant, off-farm non-participants were much better to get 1.99 quintal than their non-participant counterparts. Hence, off-farm participants produce lesser than non-participants. This could basically be due to their participation in non-lucrative off-farm activities that could add nothing to their total production. In this case food-for-work was the most important off-farm activity on which majority of the participants engaged on. Having this activity does not mean that they could be productive rather they spent half of their time by compromising their farm activities; and at the end of a month they will be given only birr 19 in cash or 3 kg(0.03 quintal) in kind which is very negligible. On the contrary, off-farm non-participants are believed to spend their time on farm activities and thereby produce better.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY IMPLICATION

One of the most important facets of off-farm activities is providing employment opportunities and additional income for rural households more particularly during the slack time. Besides, off-farm participation has a multifaceted effect on agricultural production in such a way that it paves the way for ease access of inputs and on the other hand it negatively shares the time to be allocated for farm activities. By and large, it is one of the best means of risk minimization. This research paper has tried to examine the underlying determinants of off-farm participation and the impact of participation on crop yield in Tigray region, Ethiopia. The probit regression result revealed that off-farm participation was positively influenced by gender, education, working people, number of pack animals, credit access and dummy location one, while age, land size and dummy location two influenced off-farm participation negatively. In a nut shell, even though some people do participate in off-farm activities on the basis of their internal motivation or demand driven, majorly a push driven participation has been investigated. Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression result revealed that off-farm participation has a negative and statistically significant impact on crop yield where off-farm non-participants were found to be better producers unlike their counter parts.

Without the shadow of doubt, instigating off-farm participation is the only way-out and the sole alternative that smallholder farmers need to follow basically to accommodate their seasonal and fluctuating agricultural production. In doing so, an inclusive non-farm activities training need to be given for the community like on weaving, leather and leather products training like shoe and mat making, leather strap; carpentry and some other activities. Hence, investment on human resource actually on to education is highly required (both short-term and long-term trainings). The current adult education, being propagating, need to be strengthened since literate households (those who simply can read and write) were found to be better participants unlike illiterate farmers. On the other hand, access to credit need to be propagated basically to solve liquidity problems and thereby serve as off-farm startup capital.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Abebe DB (2008). Determinants of off-farm participation decision of farm households in Ethiopia. Agrekon 47:1.

|

|

|

|

Adebiyi S, Okunlola JO (2013). Factors Affecting Adoption of Cocoa Farm Rehabilitation Techniques in Oyo State of Nigeria. World J. Agric. Sci. 9(3):258-265.

|

|

|

|

|

Adewunmi IO, Awoyemi TT, Omonona BT, Falusi AO (2011). Non-farm income diversification and poverty among rural farm households in Southwest Nigeria. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 21:1.

|

|

|

|

|

Alaba AO, Kayode SK (2011). Non-farm income diversification and welfare status of rural households in South West Zone of Nigeria. Conference paper presented for IFPRI.

|

|

|

|

|

Asenso-Okyere K, Jemaneh S (2012). Increasing Agricultural Productivity & Enhancing Food Security in Africa: New Challenges & Opportunities. Synopsis of an International Conference, International Food Policy Research Institute Washington, Dc.

|

|

|

|

|

Babatunde RO, Olagunju FI, Fakayode SB, Adejobi AO (2010). Determinants of Participation in Off-farm Employment among Small-holder Farming Households in Kwara State, Nigeria; PAT December. 6(2):1-14.

|

|

|

|

|

Babatunde RO, Qaim M (2009). The role of off-farm income diversification in rural Nigeria: Driving forces and household access. Paper Presented at the center for the study of African Economies (CSAE) conference, Economic Development in Africa, March 22-24, University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

|

|

|

|

|

Berg M, Kumbi G (2006). Poverty and the Rural Non-Farm Economy in Oromia, Ethiopia', International Association of Agricultural Economists Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, August 12-18. Int. Assoc. Agric. Econ. pp. 1-17.

|

|

|

|

|

BoARD (2011). Government of National Regional State of Tigray Five Years (2010/11 - 2014/15) Growth & Transformation Plan, Mekelle, Tigray, government printer.

|

|

|

|

|

CSA (2007). The Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia government printer.

|

|

|

|

|

Dercon S, Woldehanna T (2005). Shocks and Consumption in 15 Ethiopian Villages, 1999-2004'. Afr. Econ. 14:559-585.

Cross

|

|

|

|

|

Diao X, Nin Pratt A (2007). Growth options and poverty reduction in Ethiopia –An economy-wide model analysis. International Food Policy Research Institute, Development Strategy and Governance Division, 2033 K St., NW, Washington, DC 20006, USA; Food Policy 32 (2007) 205–228 available online at www- siencedirect.com

Cross

|

|

|

|

|

Haggblade S, Hazell PBR, Reardon T (2007). Transforming the Rural Nonfarm Economy: Opportunities and Threats in the Developing World. (1st edn). Baltimore: International Food Policy Research Institute.

|

|

|

|

|

Haggblade S, Hazell PBR, Reardon T (2009). Transforming the Rural Non- Farm Economy: Opportunity and Threats in the Developing World', IFPRI Issue Brief No. 58. Washington DC. International Food Policy Research Institute.

|

|

|

|

|

Haggblade S, Hazell PBR, Reardon T (2010). The Rural Nonfarm Economy: Prospects for Growth and Poverty Reduction. World Dev. 38(10):1429-1441.

Cross

|

|

|

|

|

Israel GD (1992). Determining Sample Size. Program Evaluation and Organizational Development, IFAS PEOD-6, Series of Agricultural Education and Communication Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida; available at EIDS web site at

View.

|

|

|

|

|

Kaija D (2007). Income Diversification and Inequality in Rural Uganda: The Role of Non-Farm Activities. A paper prepared for the Poverty reduction, Equity and Growth Network (PEGNeT) Conference, Berlin, September 6-7, 2007.

|

|

|

|

|

Merima A, Peerlings J (2012). Farm households and nonfarm activities in Ethiopia: does clustering influence entry and exit? Agric. Econ. 43:253-266.

Cross

|

|

|

|

|

MoARD (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development) (2010). Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ethiopia's agriculture sector policy and investment framework: Ten year road map (2010-2020). Final Report

|

|

|

|

|

Rios AR, Masters WA, Shively GE (2008). Linkages between Market Participation and Productivity: Results from a Multi-Country Farm Household Sample. Prepared for presentation at the American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Orlando, Florida, July 27-29, 2008.

|

|

|

|

|

Shumet A (2011). Analysis of technical efficiency of crop producing smallholder farmers in Tigray, Ethiopia. MPRA Paper No. 40461, posted 6. August 2012 13:41 UTC Available online at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Shumet A (2011). Analysis of technical efficiency of crop producing smallholder farmers in Tigray, Ethiopia. MPRA Paper No. 40461, posted 6. August 2012 13:41 UTC Available online at

View

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (2008). The Growth Report: Strategies for Sustained Growth and Inclusive Development. Washington D.C., Commission on Growth and Development, World Bank or The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

|

|

|

|

|

Woinshet A (2010). Participation into off-farm activities in rural Ethiopia: who earns more? MA Thesis, Graduate School of Development Studies, The Hague, The Netherlands.

|

|

|

|

|

Woldehanna T (2002). Rural farm/non-Farm Income Linkages in Northern Ethiopia', in B. Davis, T. Reardon, K. Stamoulis and P. Winters (eds) Rome: FAO. pp. 121-144.

|

|

|

|

|

Zahonogo P (2011). Determinants of non-farm activities participation decisions of farm households in Burkina Faso. J. Dev. Agric. Econ. 3(4):174-182.

|

|