ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to examine factors influencing household income from small scale irrigation schemes using a case study of a government funded irrigation scheme of Etunda and a community initiated irrigation scheme of Epalela in Namibia. A weighted least square model was used to analyze data that was collected from household heads from the schemes. The key finding of this paper were that small scale irrigation is dominated by male farmers. In terms of factors influencing household income levels from government funded irrigation scheme gender whereas for community initiated scheme access to farm equipment was the main determinant, respectively. It is interesting to note the estimated coefficient were negative implying that as age increase the productivity will be reduced implying that the requirement for policy shift. The implication is that there is need for policy instruments to address gender balance. Moreover, it is highly recommended to (i) strengthen technical and organizational capacity (farmers associations, groups, cooperatives) of farmers, (ii) strengthen producers’ human capital so as to improve their ability to draft viable business plans and record keeping, and (iii) to extend public sector support to community initiated irrigation schemes in the area of technology and irrigation infrastructure required.

Key words: Small scale irrigation production, weighted least square model, institutional arrangements, livelihoods.

The vast majority of the resource poor farmers in sub-Saharan Africa rely on rain-fed agriculture for their livelihood. This thereby makes them to be vulnerable to the highly variable and unpredictable rainfall whereby the period of rainfall in Africa has a ten to fifteen days delay at critical stages in crop growth which thereby spell disaster for thousands, even millions, of farmers in Southern Africa. For example, the United Nations estimates about 15% world’s population live undernourished today, this accounted for that about 870 million people (FAO, 2013), the highest prevalence of undernourishment in sub-Saharan Africa, which is that almost 16 000 children die from hunger related causes the ratio being one child every five seconds (FAO/WFP, 2012). Periodic drought and famine have become a common phenomenon in the sub-Saharan Africa as shown by frequent devastating droughts, floods, and famines. Consequently, there has been drastically reduced economic growth rates, serious malnutrition among children which have compounded the already serious impacts of malaria, HIV/AIDS, and other diseases (FAO/WFP, 2012).

Namibia has not been spared from the challenges faced by the agriculture sector as about two-thirds of its population (1.5 million) live in communal lands and are dependent on rain-fed agriculture (Namibia Statistics Agency, 2010). The high income inequality (with estimated Gini coefficient at 0.59), high unemployment (with 29% unemployment rate), and high poverty incidence (with estimated rate of 21% of individuals consumption below $1.25/day) (World Bank, 2013) are making the situation even worse. Investment in irrigation is often identified as one of the possible responses to this problem, and has had considerable success in Asia in terms of achieving national as well as local food security, reducing poverty, and stimulating agricultural growth (FAO/WFP, 2012). In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), irrigation investments never kept pace with those in Asia and for that reason region has the lowest percentage of cropped area under irrigation (FAO/WFP, 2012).

Although there has been serious call to increase irrigation investments in SSA (IFAD, 2013), a critical review of budget commitments to the agriculture and particularly irrigation development in the region does not show much practical progress. Research however shows that increasing investments in irrigation projects is a sustainable option that can make a major contribution to long term economic growth given that low-cost irrigation technologies can be affordable to the farmers (FAO/WFP, 2012). Within that backdrop, the government of Namibia’s agriculture policy has been developed as part of poverty alleviation strategy after the acknowledgement of the potential of irrigation development. This has been pronounced clearly in the Green Scheme Policy that was formulated in 2004 in line with the national vision 2030 (GRN, 2008a; Werner, 2011). The Namibian irrigation strategy is modeled on joint enterprise that tie small scale irrigation farming units to an adjacent commercial irrigation so that the small scale irrigation schemes would learn from the experience of the large scale irrigation scheme’s operations.

In Namibia, FAO has identified about 47,300 ha that can be put under irrigation production, though currently, only about 0.2% of the potential irrigation land is utilized (FAO/WFP, 2012). Namibia has invested about N$1.4 billion in the establishment of irrigation (Green Scheme projects) mainly in Karas, Kavango, Kunene, and Omusati regions (GRN, 2008a). Communities around the country have also mobilized resources to initiate small scale irrigation schemes. While a lot has been invested in the irrigation projects, there still remain misgivings on the performance and quantified income levels accruing to the participating households as also alluded to by Werner (2011). This paper therefore compared the contributions of the small scale irrigation schemes to households’ income using a case study of Etunda government funded and Epalela community initiated irrigation schemes. The paper used data from Omusati region which is part of the country with high irrigation potential.

Data was collected from small scale irrigation farmers at Etunda government funded irrigation scheme and Epalela community initiated irrigation scheme. Etunda irrigation scheme is located at about 50 km west of Outapi town in Omusati region and its 900 ha large of which 450 ha are reserved for large scale commercial irrigation with the remaining 450 ha being divided into 3 ha plots for small scale irrigation. A service provider was appointed to provide farmers with mechanization services, while the local Agricultural Development Centre provides farmers with extension services (GRN, 2008b). Epalela community initiated irrigation scheme is located at about 40 km west of Outapi, on the Oshakati-Ruacana main road in Omusati region. The scheme was initiated in the 1990s by the local community to harness the potential of Olushandja/Etaka earth dam and the Calueque–Oshakati water canal. There are 65 small scale irrigation farmers at Epalela, farming under the umbrella name Olushandja Horticulture Project Producers Association (OHPA). These small scale farmers are responsible for their individual plots’ irrigation development and its management (GRN, 2008a).

Thirty-four respondents were randomly selected out of 67 small scale irrigation farmers from Etunda government funded irrigation scheme, with 33 out of 65 small scale irrigation farmers being randomly selected from Epalela community initiated irrigation scheme. This sample size was considered sufficient due to (i) the population and the livelihood activities around the study area are homogenous, (ii) dispersion of the small scale farmers, time and cost could not allow covering all those 132 farmers.

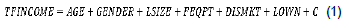

To create well-grounded relationship among the variables influencing farm productivity; at first Ordinary Least Square was tested. However, due to the presentence of heteroscedasticity and multicollinearity problems, the Weighted Least Square (WLS) model was found to be the right estimator. The model is specified as follows:

where TFICOME denoted the total farm income; AGE represents age of the farmer; GENDER is a dummy variable for gender that is one for a male farmer and zero for a female farmer; LSIZE is the irrigation plot size; FEQPT represents a dummy variable for ownership of farm equipment; DISMKT is the distance to the local market; LOWN is land ownership; and C represents the constant in the equation.

Furthermore, to examine the weight and magnitude of influence (that is, to measure elasticity), model was transformed to log form (Assaf and Sima, 2005). Weighted least squares regression is used to describe the relationship between the process variables factors influencing farm productivity. The model reflects the behavior of the random errors and it can be used with functions that are either linear or non-linear in the parameter characterization (Koenker, 2000). It is important to note that the weight for each observation is given relative to the weights of the other observations; so that different sets of absolute weights can have identical effects. The advantage of WLS is (i) it is an efficient method that makes good use of small data sets; (ii) it also shares the ability to provide different types of easily interpretable statistical intervals for estimation, prediction, calibration, and optimization; and (iii) WLS enjoys its ability to handle regression situations in which the data points vary in quality (Dalén, 2005; Elisson and Elvers, 2001; Eurostat, 2006; Haan et al., 1999; Kadilar and Cingi, 2006).

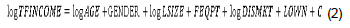

In terms of gender of the respondents from Etunda, 62% were male and 38% being female and at Epalela 85% were male with 15% being female (Table 1). What can be deduced is that the small scale irrigation projects are dominated by male headed households. The Namibian Government’s four major development objectives in the First National Development Plan (NPC, 2012) were to reduce poverty and to enhance women participation in farming sector as the most effective way to reduce poverty. In this light, it seems that at Etunda, there is significant participation of female household heads in irrigation farming, though at Epalela a lot is still to be done to address gender imbalance in the irrigation sector. Thus, the results have serious implications on policy to improve the low participation of women in irrigation farming system. This is despite government efforts and policy pronouncements that seek to promote gender equity in the agricultural sector. Therefore, government should proactively seek to support more female households’ participation in the sector. In terms of education level of the respondents at Etunda, 53% of the respondents had at least secondary level education with only 5.9% having no formal education. At Epalela on the other hand, 78.9% had at least attained secondary education with only 3% having no formal education. What can be deduced from the results is that the majority of the participants have a reasonable level of education needed to manage and make informed decisions on farming. However, these statistics will not say much about factors influencing household income levels from the schemes. For that reason further analysis was performed.

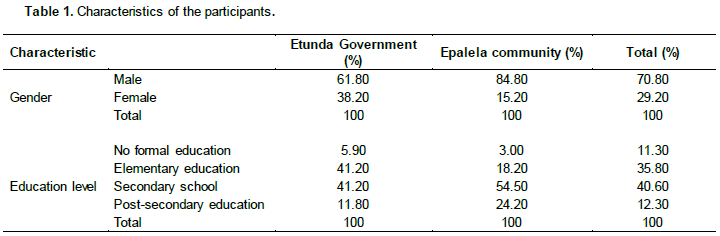

With regards to factors influencing total farm income, have a linear relationship, that is, each and every explanatory variable has its own impact for productivity, that is significant at P-value less than 1% (Table 2).

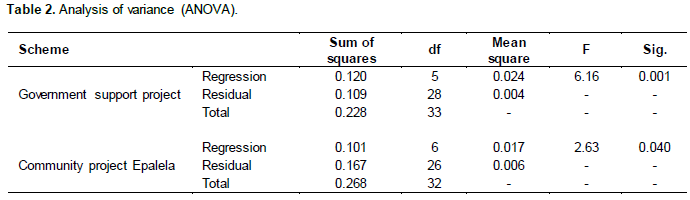

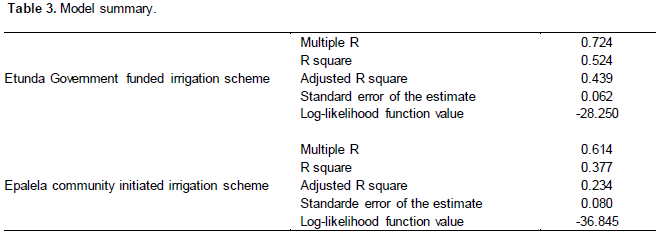

Factors affecting total farm income are reported in Table 3. The overall explanatory power is quite high at 73 and 61% for government support project and community support project, respectively.

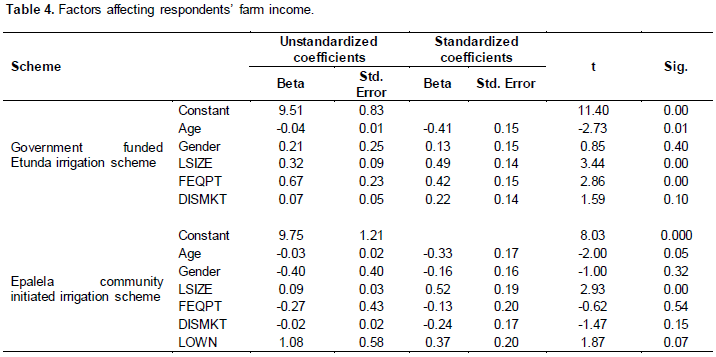

Studies elsewhere have indicated that farm productivity and income levels are influenced by multitudinous factors which can be summarized into five categories, that are economic growth and the overall development level of a country, macroeconomic factors, demographic factors, political factors, and historical, cultural, and natural factors (Eicher and Garcia, 2000; Kaasa, 2003; Sarel, 2015; Stiglitz, 2012; Stiglitz et al., 2009). In this paper, the constant is shown to be significant, at one percent with an estimated coefficient of 9.51 and 9.75 for government project and community project, respectively. This implies that the unexplained factors have a bigger influence for farm productivity and resultant income levels (Table 4).

Age was found to be critical in influencing income levels derived from the irrigation activities for both schemes. This concurs with what has been established in the development literature specifically from policy discussions. For example, the World Bank recommends fostering participation of young people in economic development as a strategy to achieve sustainable development (World Bank, 2013). As shown in Table 4, age has relatively smaller negative estimated coefficients at 0.04 and 0.03, respectively for government and community initiated schemes, respectively. The implication is that as the participant gets older the overall productivity will eventually decline (IFAD, 2013). The explanation is also very clear because farming activities at the schemes are not highly mechanized, thus requires human physical effort. So, as one gets older then the energy to perform demanding tasks at the farm becomes less hence may end up producing less demanding crops which will not bring in higher income. However, it is very inelastic, that is one percent increase in age will only increase productivity by 0.04 and 0.03%, respectively (Table 4). For example, the average age of the participants were around 48 and 45 years old for government and community project, respectively, with the mode being 43 years in both schemes. The implication is that there is limited participation by young farmers at the two schemes. As has been articulated in NDP4, its government policy to redress income inequality, accelerate high economic growth, increase employment, and the eradication of poverty (NPC, 2012). However, policy implication of the paper’s findings is that it seems that irrigation initiatives have failed to enhance participation by youth in irrigation projects at the two irrigation schemes. For this reason such interventions have not succeed to narrow down the income inequality gap and also high unemployment levels particularly for the youth.

As indicated in Table 4, land size and access to farm equipment were found to be positive and significant at 1% to influence household incomes from irrigation activities in both Etunda and Epalela irrigation schemes. Land size’s influence on income operates by way of the fact that those with larger plots can have diverse cropping systems which will in the end result in them earning more from the sale of the produce. Irrigation systems demand that the participants should have operational irrigation equipment like pumps and tractors and related machinery. Those with such equipment can take advantage of cropping opportunities that will result in their harnessing marketing opportunities. This is particularly true for Epalela irrigation scheme where community members have to finance their own operations. Even for Etunda inefficient management of the irrigation equipment particularly irrigation pumps have been blamed for poor cropping systems and missing of market opportunities. However, distance to the market was found to be insignificant.

Despite the fact that the research by IFAD (2013) shows that distance to the market is crucial in the study, it was not the case. The explanation could be that at Etunda government, products are collected through AMTA agents from the farmers and transport them to the market.

Land ownership was also found to be significant at 10% in community initiated irrigation scheme. The explanation was that community members own their land and can invest in its development that will lead to the unlocking of its potential unlike at Etunda where the members have short term contracts with government as was also established by Nekwaya (2008). Due to short contracts farmers may not invest on the land as they will not be assured that their contracts will be renewed. It is thus little wonder why at Epalela participants indicated that they have invested more on their plots as they have long term user rights to their land hence they invested more on irrigation equipment which would result in realizing more income from the irrigation scheme. The implication is that government should revisit its irrigation policy and give the beneficiaries longer term leasehold interest to encourage the farmers to invest more on the land and hence earn higher income.

During the interviews, some of the farmers raised the following concerns: (i) although government provides agricultural extension services across the country, there are no feedback mechanism to assess the level of satisfaction with the quality of extension services they have received; (ii) there is no inclusiveness during policy formulation as beneficiaries of small scale irrigation farmers feel left out during designing of the projects and that (iii) there is a lack of coordination in the administration, preparation, and design of strategic sustainable solutions for their multitude challenges in their irrigation system. The respondents also feel there is lack of transparency in project preparation and choice and inadequate monitoring of performance of the irrigation projects

Within the aforementioned backdrop, one would suggest that strengthening of the small scale irrigation farmers’ social capital is an important policy strategy. The farmers can use their social capital to gather requisite information they cannot get from the extension services, to create local savings schemes that can be useful financial ‘stores’ to be drawn from during times of stress. Another important policy implication is that there is need for government and stakeholders to design an economical viable model of small scale irrigation projects that is more focused on commercialization of the sector than small scale so as to achieve the objectives of food increased production, income generation, and job creation.

The small scale irrigation schemes are dominated by male headed households. This is despite government’s efforts to redress the gender imbalances in the economic space. For that reason it is suggested that government implements affirmative policies that will give preference to female headed households in future irrigation schemes allocation. The study also established that age of the farmers, land size, land ownership and access to farming equipment which were the main factors influencing household income from the farming activities at the two irrigation schemes.

While gender and age at Etunda irrigation scheme and access to farm equipment at Epalela community irrigation scheme were found to be significant, these are inelastic implying that heavy intervention on these factors would make small contributions on the changes in income. What this means is that at the small scale irrigation farming schemes, there are other factors other than these which have greater influence on income levels. However, it is interesting to note that at Etunda age has a negative estimated coefficient implying that as age increases the productivity will be reduced. In such case, a policy option will be to promote youth to venture to irrigation farming even for Epalela. However, there is also need for policy that will address the gender imbalance at both just like at Etunda government policy instrument needs to focus on addressing gender balance.

It is therefore recommended that government and its stakeholders should strengthen capacity and organizational institutions of the farmers like farmers’ associations, commodity groups, and cooperatives of the small scale irrigation farmers. To increase income levels of the irrigation farmers, it is also recommended for strengthening producers’ understanding of socio-economic aspects like business plans, record keeping, and related business management systems for small irrigation. It is also recommended that government revisit the land size and tenure policy for the small scale irrigation scheme beneficiaries and to provide small scale irrigation farmers with appropriate technology and infrastructure required by them to increase their income levels.

Women play a major role in society, especially in terms of food security and it is therefore important for the government to encourage the participation of women in decision-making and training programs designed innovatively to improve small scale irrigation projects. Women empowerment is important, especially in terms of access to credit, land ownership, and income generating opportunities such as small scale irrigation projects. Given marketing challenges faced by small holder farmers, small scale irrigation farmers included the government and other stakeholders involved should develop policies to enhance market information dissemination and infrastructure development for irrigation products. The formation of small scale irrigation schemes cooperatives and/or association can enable the farmers to pool their resources for production intensification. It is therefore suggested that government and other stakeholders should come up with innovative ways to support the farmers with technical training, access to loans and credit lines.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Assaf E, Sima J (2005). Voorburg Group on Service Statistics, Service Price Index for Investigation and Security Services, Central Bureau of Statistics, Israel, August 2005. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

Dalén J (2005). Sampling Issues in Business Surveys. Pilot Project 1 of the European Community's Phare 2002 Multi Beneficiary Statistics Programme, Quality in Statistics.

View

|

|

|

Eicher T, Garcia PC (2000). Inequality and growth: The dual role of human capital in development. CESifo Working Paper No 355; Nov. 2000

|

|

|

|

|

Elisson H, Elvers E (2001). Cut-off sampling and estimation, Statistics Canada International Symposium Series – Proceedings.

|

|

|

|

|

Eurostat H (2006). Eurostat. Handbook on methodological aspects related to sampling designs and weights estimations, Version 1.0, July 2006.

|

|

|

|

|

FAO/WFP (2012). The State of Food Insecurity in the World. Available

View accessed 30 November 2015

|

|

|

|

|

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organsiation) (2013). The State of Food and Agriculture 2013.

View

|

|

|

|

|

GRN (2008a). High-Level Conference on: Water for Agriculture and Energy in Africa: the Challenges of Climate Change. Sirte, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, 15-17 December 2008. National Investment Brief, NAMIBIA.

|

|

|

|

|

GRN (2008b). Green Scheme Policy. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia.

|

|

|

|

|

Haan JE, Opperdoes CM, Schut J (1999). Item Selection in the Consumer Price Index: Cut-off Versus Probability Sampling, Surv. Methodol. 25:31-41.

|

|

|

|

|

IFAD (2013). The importance of scaling up for agricultural and rural development: And a success story from Peru. IFAD Occasional Paper 4. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development.

|

|

|

|

|

Kaasa A (2003). Factors influencing income inequality in transition Economies. University of Tartu Faculty of Economics and Business Administration.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kadilar C, Cingi H (2006). New Ratio Estimators Using Correlation Coefficient, InterStat.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Koenker R (2000). Galton, Edgeworth, Frisch, and prospects for quantile Regression in econometrics. J. Econom. 95:347-374.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Namibia Nature Foundation (2010). Land Use Planning Framework for the Kavango Region of Namibia within the Okavango River Basin. Windhoek.

|

|

|

|

|

National Planning Commission (NPC) (2012). Republic of Namibia Namibia's Fourth National Development Plan 2012/13 to 2016/17.

|

|

|

|

|

Nekwaya ST (2008). Irrigation Performance Improvement in Small Scale Farms: Case Study of Etunda Irrigation Scheme-Namibia. Florentina Strudiorum Universitas.

|

|

|

|

|

Stiglitz J (2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future, W. W. Norton & Company, USA

|

|

|

|

|

Stiglitz J, Sen A, Fitoussi JP (2009). Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, Available at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Werner W (2011). Policy Framework for Small scale Gardening. Cuve Waters Paper No 8. Cuve Water Research Co-operation, Windhoek, Namibia.

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (2013). Engendering Development through Gender Equality in Rights, Resources, and Voice. Oxford University Press, New York.

|

|