ABSTRACT

Teachers like all other professionals need to undergo continuous professional development through in-service training to upgrade their skills and the competencies in the profession. This paper examined the availability of in-service training to teachers of the deaf in Ghana as well as the requirements for the provision of in-service education. To achieve this, ninety-four teachers and four administrators from the schools for the deaf from ten regions were sampled for the study. Questionnaire and interviews were used to collect data. The data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. The study revealed that in-service training programmes are highly irregular. Insufficient funds have also been identified as one of the major factors hindering the organization of in-service education. Key recommendations are that staff development should be viewed as a policy issue, as a necessity and continuous process. Thus, more resources should be devoted to staff development at regular intervals.

Key words: In-service training, professional development, needs, access, teacher, deaf.

The training of teachers has long been recognised as a key factor in the quality improvement of educational systems and the science of developing a good teacher is the domain of professional development. The idea of one period of initial training could be sufficient for an entire career seems outmoded in the field of education (Montrieux et al., 2015). It is now increasingly recognised the world over that the education of all teachers ought not to be exclusively pre-service education. In-service training is an important component in the education system, and plays a key role in the behaviour of society. Thus, there is widespread agreement that in-service education and training for professional development is an essential ingredient in the process of teacher professionalism to meet the pace of social and educational change.

The upgrading and progressive extension of programmes of initial teacher training have received concrete attention world-wide. In Ghana, there have been many educational reforms since independence. These

include the New Structure and Content of Education of 1974, the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) of 1987 and the Educational Reform Review Committee of 2004 (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2016).The FCUBE aims at providing quality education for all pupils, increase access to and making education affordable to all children of school going age and changing the curriculum to meet the needs of the people and the nation. To achieve this, it is necessary to restructure the existing programmes as well as making provisions to up-grade teachers in the service through in-service training.

A primary concern of in-service training is the provision of its requirements and of its accessibility to the target professionals on regular basis. There are no clear cut policies as to how, and at what interval in–service training should be provided. This has led to lack of well-defined programmes for upgrading teachers. Such situations leave teachers for decades in class to contend with moment-to-moment classroom challenges with only the initial training received at college (Humphrey, 2014). Such has often been the case in many special schools in Ghana, resulting in a trend where teachers are generally not conversant with educational changes and innovations. Indeed, the structure of special education administration in Ghana is itself quite problematic. While the director of special education is in charge at the districts and schools levels, teachers are answerable to district and regional directors, resulting in a trend where Special Education Division has minimum control of the nature of in-service programmes organised on district and regional levels (Lawrence and Anastasiou, 2015). The inappropriateness of the externally designed in-service training activities has been extensively commented and written about. Though avenue for teacher education through in-service exist; the prevailing in-service training programmes however, are not effective as they are externally designed without the involvement of the teacher (Malcolm, 2006). They are also presented in a didactic manner which does not help teachers to deal with actual classroom situation. Thus, In-service training activities, designed for the special educators have become even more critical to teachers of the deaf so that they will continue to provide good education for deaf children.

Statement of the problem

Trends in education are changing; teaching itself is complex and requires constant learning and continual reflection, and so there is the need for teachers at all levels not only to update their skills and knowledge, but also to totally transform their roles as educators and establish new expectation for pupils and schools. Teachers, like all other professionals, need to undergo a Continuing Professional Development (CPD) programmes in order to keep abreast with trends in the profession. Even though CPD can be achieved through reading and short courses in the area, the traditional way in which teachers receive CPD is through in-service training which in most cases in the Ghana Education Service does not exist. Lack of access to further development for any staff has its negative effects, but in-service activities are highly irregular for teachers of the deaf in Ghana.

Teaching and learning needs of the deaf

Teaching and learning needs of the deaf require an urgent prerequisite for centralized information dissemination. Recent evidence suggests that this will provide a wide range of resources for professionals and parents responsible for the education of deaf students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (Wenglinsky, 2005). Previous studies (Iva and Ronnie, 2016) have reported the development of new technologies to effect positive change in the education of students who are deaf to acquire knowledge. Knowledge has the most important characteristic of an effective teacher (Khojastehmehr and Takrimi, 2009), but some research (Marschark et al., 2015) has shown that the academic achievement of deaf students may be influenced by their teachers' knowledge of the content. Thus, the effects of being taught by a teacher without a strong background in a field may be just the kind of outcome not captured in student scores on standardized examinations (UNESCO, 2015).

Teacher Education (preparation)

Teacher preparation is a program of professional course work that develops the required skills for serving in the classroom and will lead to certification. This includes course work in areas such as teaching methodologies, curriculum development, classroom management, and student or intern teaching fieldwork (www.ctc.ca.gov, www.teachcalifornia.org, retrieved May29, 2018). But effective teacher preparation should go beyond knowing subject matter, pedagogic and child development; it should include research by teachers (Darling-Hammond, 2000). One of the best ways for teacher education program to become and remain effective is to evaluate its current status, on an ongoing basis (Frank et al., 2014). However, an effective educational program should encompass special education needs elements in all courses of initial teacher training (Carroll et al., 2003).The training of competent teachers is considered to be the most persistent and compelling need in education since no system of education can rise above the quality of its teachers. In other words, the quality of teachers in terms of their training and awareness will determine the quality of instructions and invariably the success of the programme (Oyewumi and Adediran, 2001). Well-trained staff is essential for achieving the educational goals, while poorly trained staff impede progress (UNESCO, 2015).

Concept and meaning of in-service education and training

The terms in-service training and professional development are often used interchangeably, but have slightly different meanings. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2000), professional development signifies any activity that develops an individual's skills, knowledge, expertise and other characteristics as a teacher. These include personal study and reflection as well as formal courses. In-service education and training refers more specifically to identifiable learning activities in which practicing teachers participate. Like all members of professions, teachers need to be involved in a process of learning and reflection to improve their professional practice (Aitken: 2000). In-service training may broadly be categorized into five different types whose meaning depends on the key word: (1) induction or orientation training, (2) foundation training, (3) on-the-job training, (4) refresher or maintenance training, and (5) career development training (Armstrong, 2006). All of these types of training are needed for the proper development of extension staff throughout their service life.

In-service training/ workshops for teachers of the deaf

The significance of in-service education and training for special educators has to be seen in the context of relative scarcity of special education needs elements in initial teacher training (Golder et al., 2005).

‘The educators and other staff responsible for making decisions regarding the educational needs of students with hearing loss have limited training or experience in serving students with a hearing loss. In service thus becomes critical to educators and staff.’ (pp. 52-58).

Staff training becoming necessary is circumstance where there is evidence of lack of appropriate training and requisite experience (Avoke, 2002), but such training relating to special needs is scanty (Upton, 1991); it is an ignored topic both in general literature and research (Avoke and Yepkle, 2004). Specialist staff training is exceptional topic in journals and rarely forms the basis of research and constitutes the contents of very few books (Timperley et al., 2007). Following the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the Ghana Education Service (GES) collaboration of a framework for in-service training policy for basic education teachers, in-service activities at the school and district levels had increased in Ghana in the last few years. The training, however, does not reflect any measurable change in the work output, especially in instructional practices at the classroom level (GES, 2007). Although the aim was to establish an institutionalized structure for basic school teachers’ continuous professional development (CPD), there was no opportunity created for special teachers in the service.

Objectives of the study

The current research (i) examines the extent to which teachers of the deaf have access to in-service training (ii) explores the types of in-service activities provided for teachers of the deaf and (iii) elaborates on the types of in-service activities needed for teachers of the deaf.

The following methods and procedures were considered to arrive at the data, analysis, interpretation and discussion. The target population, sampling and sampling technique, research instruments, data collection procedure and analysis plan have been outlined.

Target population

The target population for the study included all two hundred and ninety three teachers from thirteen schools (13) for the deaf in Ghana. The breakdown of the target population is shown in Table 1.

Sampling and sampling technique

Ninety-four respondents who were selected by simple random sampling were involved in the study. They comprised three District Directors of Education, ninety teachers of the deaf and one personnel of Special Education Directorate representing about thirty percent of the total population. Respondents were made up of 43 males and 51 females.

Sampling technique

Hallberg (2013) emphasized that the quality of a population sample affects the quality of the research generalizations. Simple random sampling technique was employed to sample 94 teachers of the deaf and administrators to ensure that there was no researcher bias in selecting the respondents. Obtaining an unbiased sample is the main criterion when evaluating the adequacy of a sample (Hallberg, 2013). Purposeful sampling was employed for the three education administrators since these were people in charge and responsible for In-Service Training within their Districts or Ministry and so it was appropriate to seek their views and opinions. The Officer from the Special Education Directorate was purposely sampled as he was the only one in charge of training at the special education Directorate.

Research instruments

Likert-type questionnaires were used to collect data on the needs and access of In-Service Education and Training for teachers in Basic ‘Schools for the Deaf’. The questionnaire was used since the study was mainly concerned with variables that could not be directly observed or manipulated. The confidentiality of the study was also taken care of by the questionnaire. Ninety four questionnaires and interview guide were the main instruments used to collect data for the study. Questionnaire items were in four sections: Section A contained four items that sought to gather information concerning respondents’ background. Section B had five items seeking to gather data on the availability of in-service programmes to teachers of the deaf. Section C was made up of six items that sought to find out the type of in-service programmes provided for teachers. The last part, section D, was to sample the views of teachers on how in-service should be organised, and these consisted of seventeen items. The questionnaire was crafted into Likert scale of five responses, categorised as: Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree and Strongly Disagree.

Interview guide was also designed to engage the rest of the respondents in some sort of dialogue so that they would be able to express themselves beyond Yes or No responses. The interviews were used as a means of triangulation. Schedules for the interview were devised comprising semi-structured items. By the semi-structured method, only broad and misunderstood areas were identified and probing questions asked on them (Lynas, 2001). The interview was recorded using a Philips Dynamax2 hi-fi recorder so as to note the opinion, attitude, preferences and perception of persons of interest to the study.

Data collection procedure

Interview sessions

Interviews were conducted on one-on-one basis for three District Directors/training officers and the one personnel of the Special Education. Each session lasted about 20 to 30 min. Prior consent to be interviewed and audio recorded was sought from respondents and the purpose of the research explained to them. Hancock et al. (2007) stated that tape recorders allow the researcher to engage in lengthy informal and semi-structured interview capturing verbatim quotations in a natural conversational flow.

Administering the questionnaire

Copies of the questionnaire were administered and retrieved by the researcher within a period of one week and this was done to avoid the phenomenon of late response by the respondents (Robson, 2002). Of all the ninety-six copies of questionnaires administered there was about ninety-eight percent (98%) recovery rate.

Data analysis plan

A combined methodology approach was adopted in the analysis of data collected. Descriptive statistics were employed to answer research questions. Reponses to questionnaire were categorised according to how they related to the research questions and analysed into frequency tables using MS excel. Interviews were transcribed and analysed based on emerging themes while verbatim expressions of respondents were noted at the appropriate sections.

Validity of the research

The validity of the research was established with a pilot study. The data collection instruments were pilot tested on 10% of sample size to discover possible weakness, inadequacies, ambiguities and problems in the instrument, at the Sekondi School for the Deaf in the Western Region of Ghana. A non-probability method - convenience, was adopted for the pilot study. The data collection instruments and the sample size were considered appropriate since they had the same characteristics with study schools and sample population.

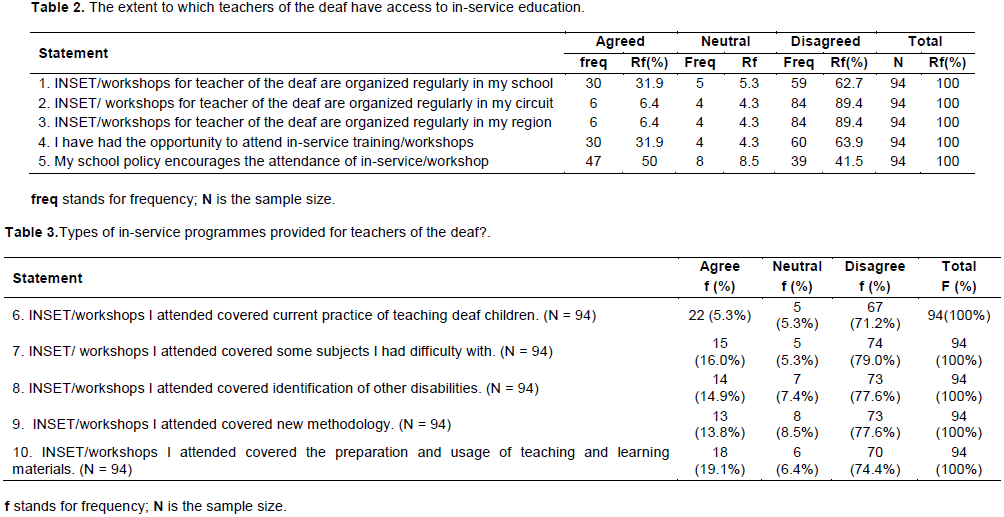

In response to the purpose for which this research was carried out, the data collected from respondents were processed into frequency and percentage tables as shown in Tables 2 to 4. Majority of the respondents were between the ages of 31-40 years. Sixty four percent of these were untrained and had been teaching for less than six years. The results together with the discussions were carried out in response to the research questions: to what extent do teachers of the deaf have access to in-service training, what types of in-service programmes are provided for teachers of the deaf and what types of in-service activities are desirable for teachers of the deaf.

Teachers access to in-service training

Results in Table 2 illustrate teachers’ responses regarding the extent to which teachers of the deaf have access to in-service education and training. About 62.7% respondents disagreed with the statement that in-service training was organized regularly in their schools, while 30 respondents, that is 31.9% agreed with the statement. Eighty four respondents, representing 89.4% said in-service training for teachers of the deaf was not regularly organized in their circuits and regions while 6 or 6.4% said it was organized. Whereas 31.9% of respondents had the opportunity to attend in-service training, 63.9% never had such opportunity (Table 2). Exactly (50%) of the respondents agreed that their school policy encouraged the attendance of in-service training, thirty-nine respondents representing 41.5% disagreed and 8.5% were unsure.

Generally, the analysis indicates that in-service training programmes were not uniformly available to teachers of the deaf but minority have opportunity. The absence of these training activities meant teachers would not have the opportunity to equip themselves with new skills required for coping with emerging trends and demands of teaching. Access to in-service education and training are highly irregular and inaccessible to teachers of the deaf. Teachers of the deaf have to contend with their day-to-day classroom challenges relying on the initial training they had. This situation however, does not ensure good education for deaf pupils. The best of pre-service teacher education cannot equip one for lifelong standing (UNESCO, 2018); it is inconceivable to assume it was adequate. Continuous growth and development is necessary for teachers especially in the light of an expanded knowledge base and continuing nature of changes that is occurring in society; the need for continuous professional growth among teachers takes on a critical new importance.All four personnel interviewed agreed that in-service education and training was irregular. It was quite revealing that two of the officers who had oversight responsibility for training did not themselves have any clue on what policy existed in that regard based on the following statement:

“In fact, I am not aware of anything that has to do with in-service training in this District, even though I have been hearing that some form of in-service training are being organized by certain agencies for teachers in the Districts; the truth is I have no idea regarding policy on in-service”(Verbatim comments from a District Education officer).

The Wa Municipal Director even though was not aware of what the policy was regarding in-service training had an established programme for in-service training sponsored by Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) for capacity building of staff and teachers of the municipality. Interestingly, all provisions were for all basic schools in the municipality. Special teachers required special training, and their training was considered expensive.

The director explained:

”As for special teachers, there is nothing like in- service education and training for them because sponsors do not want them to be part because their needs are different and expensive”.

Other issues affecting the inaccessibility of in-service education and training that emerged during the interview session was traced to the organizers. The training officer at the headquarters mentioned that organizers do not invite teachers from special schools because the officer believes special educators are perceived as being in charge of children with disabilities and not the education of children with disabilities. The findings of the study indicated that teachers in schools for the deaf did not attend in-service training activities. Consequently, some are unlikely to be abreast with innovative teaching strategies of educating the deaf. Every educational system should change with the culture, economic and technology to keep abreast with the changing demands of the time. Effective change will only occur in the classroom if teachers are involved through the process of in-service training. In-service training is designed to equip teachers with new skills required for coping with emerging trends and demands of teaching.

The unavailability of in-service programmes to teachers of the deaf as indicated by the findings of this study is in line with the one conducted by the ADB (2017). The study which was conducted on teachers of agriculture in Kwara State of Nigeria indicates that respondents (teachers) had not had the opportunity to receive any form of in-service training for five years. Society now demands more from its schools and teachers in the area of exposure and technology (Hargreaves, 2003) but this cannot be achieved with the irregular nature of in-service training for teachers of the deaf as is the case of these findings. For teachers to stay ahead, in-service training must take place on a regular basis, so that teachers are "reflective practitioners" in their classrooms and schools become "learning organizations" (Hargreaves, 2003). Samar (2014) also recommends that continuous training programmes are important for keeping the teacher abreast with rapidly developing technologies and methodologies advances in the field. The minimum qualification in the teaching profession was certificate ‘A’ and 46.9% of the teachers were below this grade and nonprofessional. In most cases, educators and other staff responsible for making decisions regarding the educational needs of students with hearing loss have limited training in serving students with a hearing loss and so the significance of in-service education and training for special educators has to be seen in the context of relative scarcity of special education needs elements in initial teacher training (Golder et al., 2005).

Type of in-service training provided for special teachers

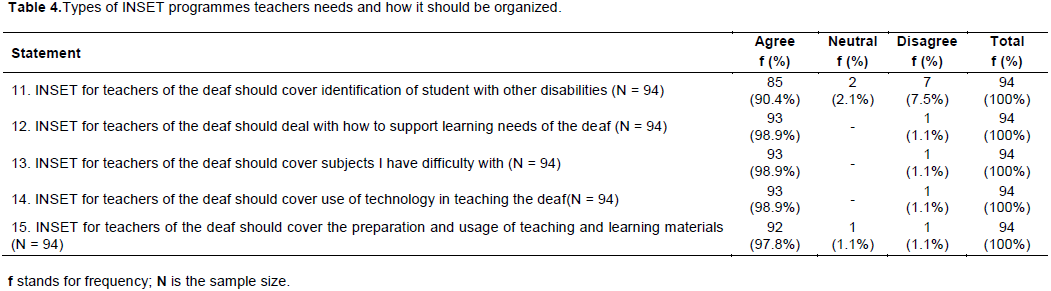

The training and facilitation of the special child is as important as the type of in-service training provided for the special education teacher. The current practice of teaching the deaf, the preparation and usage of teaching and learning materials as well as new methodologies depends on the type of training offered to the teacher. Responses from the sampled population are presented in Table 3.

From Table 4, sixty-seven respondents representing 71.2% disagreed that workshop they attended covered current practice of teaching deaf children while 24.5% of the respondent agreed it did cover. Whereas 16% of the respondents agreed that the few in-service training they attended covered some difficult subjects, seventy-four respondents representing 79% disagreed. Seventy-three representing (77.6%) of the respondents disagreed while fourteen which is 14.9% of the respondents agreed with the statement that the workshop they attended covered identification of other disabilities in deaf children. While seventy-three respondents representing 77.6% disagreed with the statement, 13.8% of the respondents agreed with the statement that workshop they attended covered new methodologies. With 74.4% of the respondents disagreeing that workshop they attended covered the preparation and usage of teaching and learning materials, 19.1% of the respondents agreed it did. On the whole, the above presentation gives the impression to presuppose that in-service education and training did not address the needs of teachers of the deaf. In an interview with a training officer at the Special Education Headquarters, it was discovered that little was being done to provide in-service education and training to teachers of basic schools for the deaf. He commented as follows:

Sign language is not the only problem; in fact the difficulties are numerous, like the preparation and usage of teaching and learning material, new teaching methodologies and even subject content (Verbatim Expression of Training Officer, Headquarters).

One of the Municipal Directors of Education noted that in-service training of teachers was largely centralized and that was accounting in part for the lack of opportunities for teachers in special schools, since many at the policy level were not aware of the support required for special teachers. He said, “There are difficulties in organizing in-service training, and so we cannot design activities to suit special teachers, everything has been centralized”.

Findings of the study indicated that in-service training programmes did not cover identified important areas like current practices in the teaching and learning of the deaf, some difficult subject matter and others. These are very important if deaf children are to get good education. When in-service training programmes do not cover present needs, then it means that teachers are not exposed to innovative teaching strategies. This obviously is not in congruent with the theory of change which states that teachers should be given regular training to enable teachers face changing demands of school and society. Ahmed (2015) in this same view argued that the changing conceptualization of special education has highlighted a need to look seriously at the pattern of training which currently exists and the way in which we attempt to deliver training.

The revealed situation is not in line with provisions stated in the policies and strategic plan for education. According to MOE (2000), Policies and Strategic Plans for Education Sector, non-residential courses are usually organized for teachers, college tutors and field officers by specially trained subject specialists at the regional or district offices. A teacher’s understanding of subject matter is very important. Ball (2000) states that teachers need to know their subject matter in depth. Understanding how to teach the subject matter in a variety of ways is the most important skill for an educator. From the analysis and discussion it has been established that the type of in-service training activities provided do not meet the in-service needs of the teachers of the deaf.

Type of in-service activities needed for teachers of the deaf

Eighty-five respondents or 90.4% of the respondents agreed with the statement that in-service for teachers of the deaf should cover the identification of other disabilities. On the other hand, 7.5% of the respondents did not think that was necessary. Majority believed the identification of other disabilities in deaf pupils was necessary in adopting appropriate methods that suit them. Ninety-three respondents representing 98.9% agreed with the statement that in-service/ workshop should deal with how to support learning needs of the deaf while one respondent or 1.1% of the respondents disagreed with the statement. An overwhelming response indicates that teachers of the deaf had some needs in terms of handling deaf children. About 98.9% of the respondents agreed with the statement that in-service training should cover some subject teachers that had difficulty teaching the deaf, while one or 1.1% of the respondents disagreed with the statement. For instance, mathematics was noted by Ray (2001) as one of the challenges the hearing-impaired children encounter during learning.

Mayberry (2002) argues that in order for hard to hear children to develop cognitively, particularly in a mathematical sense, in-service education and training should cover a wide range of meaningful mathematical experiences that are visually engaging and hands-on for the teachers. Activities should be purposeful and have relevance to everyday life so that they can be experienced in a context other than a purely mathematical one. The issue of some subjects being difficult to teach in special schools has also been identified in an evaluation on a large-scale reform in Canada in which special educators express similar concerns as reported by Fullan (2000). He indicated that almost two-thirds (63%) of the teacher respondents claimed that some subjects were more demanding or difficult than others and will need more attention on how to handle them.

Ninety-three respondents representing 99% agreed with the statement that in-service training/workshops should cover the use of technology in teaching the deaf. Only one 1% of the respondents disagreed with the statement. This is an indication that special schools need to integrate technology in the teaching of deaf pupils. This integration requires that teachers are able to use technology effectively in whatever subject they teach. Thus, this requires professional development for teachers to master technology and learn new methods of incorporating it. From the findings, the current system does not support teachers of the deaf in acquiring these skills, and so has left many teachers with little or no experience with technology. In a study which set out to determine reasons for not using technology in teaching in Canada, Ryan and Joong (2005) said 43% of teachers attributed the phenomenon to lack of time, lack of access to computers, limited resources, and a scarcity of in-service training.

Ninety-two or 97.8% of the respondents stated that there was the need for workshops to cover the preparation and usage of teaching and learning materials. No teacher should leave the training centre without a set of self-produced materials during his/her training. The needs of the teacher go beyond just sign language. There are other issues affecting teaching and learning. Strengthening the teachers’ subject knowledge base is very important and has been argued by some researchers to be critical to students’ achievements. For instance, America Educational research Association (Resnick, 2005) suggests that professional development can influence teachers’ classroom practice significantly and leads to improved students’ achievements when it focuses on strengthening teachers’ knowledge of specific subject matter content.

Organization of in-service training

As to how in-service training should be organized to benefit teachers, the findings from the interview sessions revealed that respondents will prefer programmes organized at the school level to the circuit and regional levels. Interview results established that some form of in-service training goes on in the various schools. All four officers interviewed indicated that some form of school based in-service training had been going on in the various schools for the deaf.

While the choice of duration for in-service training for teachers of the deaf is preferably five days in Ghana, a week long in-service outside school premises is preferred by teachers in Nigeria. The type of in-service activities needed by teachers of the deaf included: new methods of teaching, identification of other disabilities in deaf pupils, teaching, preparation and usage of teaching and learning materials. Interview findings also established that teachers will prefer a five days school based demonstration workshops.

Teachers of the deaf do not have regular access to in-service education and training. In-service education programmes are needed to increase knowledge and skills of teachers of schools for the deaf in dealing with the teaching and learning needs of deaf students. The few available in-service training programmes are organized without the inclusion of special education teachers. This leads to situations where in-service training does not address the needs of teachers of the deaf. Lack of funds is a major factor inhibiting the regular organization of in-service training programmes as well as the training, evaluation and monitoring of the activities of the schools for the deaf.

Teachers for basic schools for the deaf have needs in computer technology, mathematical skills, general contemporary skills and practices in lesson delivery and teaching and learning materials. Teachers for basic schools for the deaf also need regular workshops to strengthen their subject knowledge base. The lack of in-service training for teachers for basic schools for the deaf however, has limited the acquisition of these requirements.

The following recommendations are made to make the organization of in-service education and training more effective and to bring about maximum benefit to teachers of the school for the deaf in Ghana. The factors militating against the effective organization of in-service training educational programmes and their undercurrent effect on staff development in basic schools for the deaf in Ghana as outlined and discussed are basically financial and organizational.

1). The Ghana Education Service in recommendation to the Ministry of Education should make staff development an on-going process and a policy issue. This will make it possible for time and resources to be devoted to staff development through long term financial planning.

2). The regional and district directorates in collaboration with Non-Governmental Organizations such as the Catholic Relief Service should take advantage of the Quality Improvement in Basic Schools (QUIPS) programmes to strengthen the capacity of teachers of schools for the deaf.

3). Special educators should be involved in the designing and implementation of in-service programmes to ensure special schools benefit from the type of activities designed so that they can always be abreast with changing trends in the field.

4). Heads of special schools should do “needs assessment” within the school and invest part of the five percent allocation of the District Assembly Common Fund to special schools in the districts in staff development programmes. The success of the free compulsory Universal Basic education depends on a well-developed staff.

5). Heads of special schools should design programmes that will address the peculiar needs of teachers of the deaf after a through needs assessment as short time measures of dealing with classroom challenges on continuous bases. Professionals and specialist from the Special Education could be called on to design activities to address identified needs.

6). All providers of in-service training (including schools) are required to define in their strategic and annual plans the expected outcomes of the training to be provided and to identify the criteria they will use to evaluate the extent to which these outcomes have been met by teachers of schools for the deaf.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

The author would like to appreciate the diverse contribution of the following people to the success of this study: Mr. Mahama Hassan, research assistant, Education Extension Services Unit, University for Development Studies; Mr. Iddrisu Abdul-Mumeen, PhD student at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, for their technical support during the study and the write-up respectively.

REFERENCES

|

Adu-Gyamfi S, Donkoh WJ, Addo AA (2016). Educational Reforms in Ghana: Past and Present, American Research Institute for Policy Development, Journal of Education and Human Development 5(3):158-172.

|

|

|

|

Ahmed BK (2015). Disability rights awareness and inclusive education: building capacity of parents and teachers a manual for in-service training and community education, UN voluntary fund on disability.

|

|

|

|

|

Aitken JE (2000). Deafness and child development. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Armstrong M (2006). A handbook of Human Resource Management Practice, (9thEd.) London: Kogan Page Limited.

|

|

|

|

|

Asian Development Bank (ADB) (2017). Innovative Strategies for accelerated Human resource development in South Asia, Teacher Professional Development.

|

|

|

|

|

Avoke M (2002). Pattern of placement and their implication for points of exist for pupils with mental retardation: A case of two residential schools for individuals with retardation in Ghana 13:11 9-122.

|

|

|

|

|

Avoke M, Yekple Y (2004). Staff training as a component of teacher development in special education. Education for today 4 (1):13-22.

|

|

|

|

|

Ball DL (2000). Bridging practices: Intertwining content and pedagogy in teaching and learning to teach. Journal of Teacher Education 51:241-247.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Carroll A, Forlin C, Jobling A (2003). The Impact of Teacher Training in Special Education on the Attitudes of Australian Pre-service General Educators towards People with Disabilities. Teacher Education Quarterly, Australia.

|

|

|

|

|

Darling-Harmond L (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence. Education Policy Analysis Archives 8(1):1-44.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Frank CW, Mary MB, Carol AD, Kurt FG, Ronald WM, George HN, Robert CP (2014). Assessing and evaluating teacher preparation programs. American Psychological Association (APA). APA Task force report, USA.

|

|

|

|

|

Fullan M (2000). The return of large-scale reform. Journal of Educational Change 1(1)

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ghana Education Service (GES) (2007). In-service and training sourcebook

|

|

|

|

|

Golder G, Norwich B,Bayliss P (2005). Preparing teachers to teach pupils with special educational needs in a more inclusive school: evaluating a PGCE development. British Journal of special education 32(20):92-99.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hallberg L (2013). Quality criteria and generalization of results from qualitative studies, International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being 8(1):20647.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hancock B, Windridge K, Ockleford E (2007). An Introduction to Qualitative Research. The NIHR RDS EM / YH.

|

|

|

|

|

Hargreaves A (2003). Teaching in the knowledge society: Education in the age of insecurity. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Humphrey AU (2014). Challenges faced by teachers when teaching learners with developmental disability Master's Thesis Master of Philosophy in Special Needs Education Department of Special Needs Education Faculty of Educational Sciences UNIVERSITY OF OSLO.

|

|

|

|

|

Iva H, Ronnie BW (2016). Academic Achievement of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students in an ASL/English Bilingual Program. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 21(2):156-170.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Khojastehmehr R, Takrimi A (2009). Characteristics of Effective Teachers: Perceptions of the English Teachers. Journal of Education and Psychology 3(2):53-66.

|

|

|

|

|

Lawrence KA, Anastasiou D (2015). Special and inclusive education in Ghana: Status and progress, challenges and implications. International Journal of Educational Development 41:143-152.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lynas W (2001). Choosing between communications approaches. In V Newton (ed), paediatricaudiology. London: whurrpublications. Mackays of Chathean; PLC Chatham, Kents, Great Britain.

|

|

|

|

|

Malcolm L (2006). The development of in-service education and training as seen through the pages of the British. Journal of In-service Education, British Journal of In-service Education 23(1):9-22.

|

|

|

|

|

Marschark M, Shaver DM, Nagle KM, Newman L (2015). Predicting the academic achievement of deaf and hard-of-hearing students from individual, household, communication, and educational factors. Exceptional Children 81(3):350-369.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mayberry RI (2002). Cognitive development in deaf children: the interface of language and perception in neuropsychology. Handbook of Neuropsychology, 2nd Edition, Vol. 8, Part II S.J. Segalowitz and I. Rapin (Eds)

|

|

|

|

|

Ministry of Education (MOE) (2002). Policies and Strategic plans, the education section. Accra: MOE publication.

|

|

|

|

|

Montrieux H, Vanderlinde R, Schellens T, De Marez L (2015). Teaching and Learning with Mobile Technology: A Qualitative Explorative Study about the Introduction of Tablet Devices in Secondary Education. PLOS ONE 10(12):1-17.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2000). Staying Ahead: in-service training and professional development. Paris: Center for Educational Research and innovation of OECD.

|

|

|

|

|

Oyewumi AM, Adediran DA (2001). Professional preparation of teachers for inclusive classroom. The exceptional child 5(1).

|

|

|

|

|

Ray E (2001). Discovering mathematics: The challenges that deaf/hearing impaired children [email protected]

|

|

|

|

|

Resnick LB (2005). Essential information for educational policy. In teaching teachers (City) America Educational Researchers Association.

|

|

|

|

|

Robson C (2002). Real world research: A resource for scientist and practitioners-researcher (2ed) Oxford: Blackwell.

|

|

|

|

|

Ryan G, Joong P (2005). Teachers' and students' perceptions of the nature and impact of large scale reforms. In Canadian journal of educational administration and policy.

|

|

|

|

|

Samar Z (2014). Teachers' Learning and Continuous Professional Development in Lebanon: A View Gained through the "Continuous Training Project." World Journal of Social Science 2(1):16-31.

|

|

|

|

|

Timperley H, Wilson A, Barrar H, Fung I (2007). Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2015). The Right to Education and the Teaching Profession Overview of the Measures Supporting the Rights, Status and Working Conditions of the Teaching Profession reported on by Member States, 12th session of the Committee of Experts on the Application of the Recommendations concerning Teachers (CEART), 20-24 April 2015, Paris, France.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2018). Policy Guidelines on Inclusion in Education Published by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, Paris, France.

|

|

|

|

|

Upton G (1991). Issues and trends in staff training in Upton G. (ed.) Staff training and special education needs. London. David Fulton Publishers Ltd.

|

|

|

|

|

Wenglinsky H (2005).How teaching matters: Bringing the Classroom back into discussions of teacher quality. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

|

|